Abstract

Introduction

Chemoradiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx (SCCO) provides good results for locoregional disease control, with high rates of complete clinical and pathologic responses, mainly in the neck.

Objective

To determine whether complete pathologic response after chemoradiotherapy is related to the prognosis of patients with SCCO.

Methods

Data were prospectively extracted from clinical records of N2 and N3 SCCO patients submitted to a planned neck dissection after chemoradiotherapy.

Results

A total of 19 patients were evaluated. Half of patients obtained complete pathologic response in the neck. Distant or locoregional recurrence occurred in approximately 42% of patients, and 26% died. Statistical analysis showed an association between complete pathologic response and lower disease recurrence rate (77.8% vs. 20.8%; p = 0.017) and greater overall survival (88.9% vs. 23.3%; p = 0.049).

Conclusion

The presence of a complete pathologic response after chemoradiotherapy positively influences the prognosis of patients with SCCO.

Keywords: Oropharynx, Carcinoma, Squamous cell, Combined chemotherapy, Neck dissection

Resumo

Introdução

O tratamento baseado em quimirradioterapia do Carcinoma Espinocelular de Orofaringe (CECOF) apresenta bons resultados no controle locorregional da doença com boas taxas de resposta clínica e patológica completas especialmente no pescoço.

Objetivo

Determinar se a resposta patológica completa após quimiorradioterapia estárelacionada aos prognósticos dos pacientes com CECOF.

Método

Os dados foram obtidos de maneira prospectiva da revisão de prontuários de pacientes com CECOF N2 e N3 submetidos a esvaziamento cervical planejado após quimiorradioterapia.

Resultados

Um total de 19 pacientes foram avaliados. Metade dos indivíduos apresentou resposta patológica completa no pescoço. Recidiva à distância ou locorregional ocorreu em aproximadamente 42% dos pacientes e 26% deles morreram. A análise estatística demonstrou uma associação entre resposta patológica completa e menor taxa de recidiva (77,8% vs. 20,8%; p = 0,017) e maior sobrevivência global (88,9% vs. 23,3%; p = 0,049).

Conclusão

A presença de resposta patológica completa após quimiorradioterapia influencia positivamente no prognóstico de pacientes com carcinoma espinocelular de orofaringe.

Palavras-chave: Orofaringe, Carcinoma de células escamosas, Quimioterapia combinada, Esvaziamento cervical

Introduction

An option in the treatment of locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx (SCCO) is chemotherapy and radiotherapy combined with organ preservation, also targeting local and regional control of the disease.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 This therapeutic approach was originally devised to be followed by a planned neck dissection in all patients.7, 8, 9 Some authors suggest, however, that this approach should be restricted to patients with N2 and N3 stage at diagnosis, or to those patients with N1 stage with partial response after treatment.10, 11, 12 However, other authors argue that a planned neck dissection must be carried out, regardless of the initial stage, considering that the pathological positivity rate after treatment reaches 30–40%.10, 13 It is also well established that patients with residual cervical disease after chemoradiotherapy have an increased risk of locoregional recurrence, as well as of distant disease.14, 15, 16, 17

Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate whether the complete pathologic response after a combined treatment with chemoradiotherapy is associated with the prognosis in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee under protocol No. 098/2008. This study included all patients with IVa or IVb stage SCCO (T1-4a, N2-3) consecutively submitted to chemoradiotherapy, followed by planned radical neck dissection 8–12 weeks after the end of the treatment, in the period from January 2008 to December 2010, and with complete response at the primary site confirmed by physical examination, pan-endoscopy, computed tomography (CT) scan, and biopsy, when needed. Complete clinical response was considered when there was no evidence of persistent disease in these examinations; complete pathologic response was considered when the specimen obtained through the planned neck dissection showed no pathological evidence of active malignancy (residual tumor). Response assessment was defined together in a multidisciplinary clinical meeting, including Head and Neck Surgery, Oncology, Radiology, and Pathology Services. Platinum-based chemotherapy was administered, with a minimal radiotherapy dose of 5000 cGy applied to the cervical bed. In this scenario, 19 patients were included, with a minimum of two years of follow-up guaranteed for all participants.

Demographic, clinical, and pathological data were obtained from medical records. The pTNM stage was revised based on the seventh edition (2010) of the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) publication. All patients were followed monthly, bimonthly, and every three, four, and six months, respectively for the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth post-treatment year. Human papillomavirus (HPV) status was assessed retrospectively at the time of completion of this study through reviewing the paraffin blocks for the presence of p16 protein; the specimen was considered positive when immunoexpression rates were above 80%. No other HPV detection methodology was performed, because of unavailability at this center.

The primary outcome studied was progression-free survival, defined as the time from diagnosis to disease recurrence (locoregional or distant). Secondarily, overall survival was studied, measured as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause. Patients alive without evidence of disease at the time of this analysis were censored at the last follow-up.

For statistical analysis, the chi-squared or Fisher's exact test was used for comparison between two qualitative variables. Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test were used for survival analysis and for comparing curves, respectively. SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc–Illinois, United States) was used for all analyzes, and the level of statistical significance was set at 5% (p ≤ 0.05).

Results

Nineteen patients, totaling 21 neck dissections, were included (Table 1) with a median of 28 months of follow-up. Most patients were male (78.9%) in the fifth decade of life (44–76 years), and were smokers and drinkers. Only one positive p16 case was detected. Complete clinical response was observed in 12 patients (63.2%) and complete pathological response in ten (52.6%). Eight cases (42.2%) had disease progression and five (26.3%) suffered disease-related death.

Table 1.

Descriptive data of patients included in this study.

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 15 (78.9%) |

| Female | 4 (21.1%) |

| Age (years)a | 55.8 ± 8.1 |

| Primary site | |

| Soft palate | 1 (5.3%) |

| Tongue base | 5 (26.3%) |

| Vallecula | 3 (15.8%) |

| Palatine tonsil | 8 (42.1%) |

| Lateral wall | 2 (10.5%) |

| Habits | |

| Smoking | 17 (89.5%) |

| Alcoholism | 15 (78.9%) |

| HPV-positive status (p16-positive) | 1 (5.3%) |

| Pretreatment | |

| Concomitant chemoradiotherapy | 12 (63.2%) |

| Induction chemotherapy followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy | 7 (36.8%) |

| Initial clinical stage | |

| T stage | |

| T2 | 4 (21.1%) |

| T3 | 8 (42.1%) |

| T4 | 7 (36.8%) |

| N stage | |

| N2a | 7 (36.8%) |

| N2b | 3 (15.8%) |

| N2c | 2 (10.6%) |

| N3 | 7 (36.8%) |

| Complete clinical response | 12 (63.2%) |

| Complete pathological response | 10 (52.6%) |

| Progression | |

| Locoregional | 4 (21.1%) |

| Distant | 4 (21.1%) |

HPV, human papillomavirus.

Mean ± standard deviation.

In the univariate analysis, none of the demographic, clinical, or pathological variables were associated with complete pathological response, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis: variables associated with complete pathological response.

| Variable | Complete pathological response |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p-value | |

| Age (years: mean ± standard deviation) | 55.3 ± 9.0 | 56.4 ± 7.4 | 0.780a |

| Gender | 0.303b | ||

| Male | 6 (66.7%) | 9 (90.0%) | |

| Female | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (10.0%) | |

| Primary site | 0.543c | ||

| Soft palate | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Tongue base | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (40.0%) | |

| Vallecula | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (10.0%) | |

| Palatine tonsil | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (40.0%) | |

| Lateral wall | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (10.0%) | |

| Previous treatment | 1.000b | ||

| Concomitant chemoradiotherapy | 6 (66.7%) | 6 (60.0%) | |

| Induction chemotherapy followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (40.0%) | |

| Cervical irradiation dose | 0.370b | ||

| 5000 cGy | 6 (66.7%) | 4 (40.0%) | |

| 7000 cGy | 3 (33.3%) | 6 (60.0%) | |

| Primary neoplasia differentiation | 0.289c | ||

| Well differentiated | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 7 (77.8%) | 10 (100.0%) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Initial clinical stage | |||

| T stage | 0.326c | ||

| T2 | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (10.0%) | |

| T3 | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (40.0%) | |

| T4 | 2 (22.2%) | 5 (50.0%) | |

| N stage | 0.462c | ||

| N2a | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (40.0%) | |

| N2b | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (20.0%) | |

| N2c | 2 (22.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| N3 | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (40.0%) | |

| Complete clinical response | 0.650b | ||

| No | 4 (44.4%) | 3 (30.0%) | |

| Yes | 5 (55.6%) | 7 (70.0%) | |

Mann–Whitney test.

Fisher's exact test.

Chi-squared test.

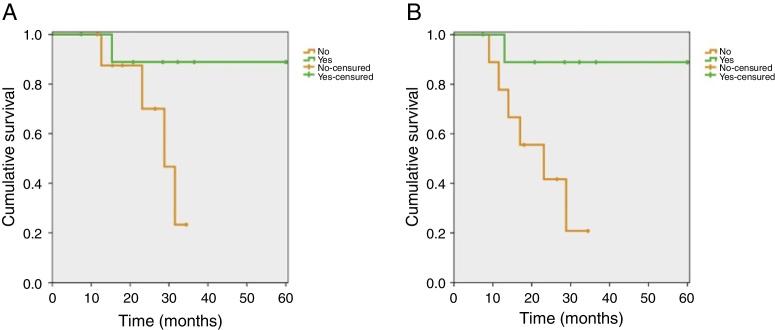

Survival analysis showed that patients with complete pathological response had higher progression-free survival (77.8% vs. 20.8%; p = 0.017 – log-rank test) and overall survival (88.9% vs. 23.3%; p = 0.049 – log-rank test) rates, as detailed in Fig. 1. The medians for progression-free survival and overall survival for patients with residual cervical disease were 23.1 and 28.8 months, respectively, while patients with complete pathologic response did not achieved these medians over the 60-month follow-up. Bearing in mind that this was a retrospective study, in the analysis of these findings the power of this estimate was calculated using the method of comparison between two proportions. Faced with the obvious differences between Kaplan–Meier curves (88.9% vs. 23.3% for progression-free survival and 77.8% vs. 20.8% for overall survival, respectively for patients with vs. without complete pathologic response), the inclusion of 19 patients in this study resulted in an analytical power for this estimate in excess of 95%. For a conventional analysis (80% test power and 5% statistical significance), it was estimated that a sample between eight and 12 patients would suffice to demonstrate these findings, mainly due to the great difference between the curves.

Figure 1.

Overall survival (A) and progression-free (B) curves stratified for pathological response (88.9% vs. 23.3%; p = 0.049 – log-rank test for overall survival and 77.8% vs. 20.8%, p = 0.017 – log-rank test for survival free of disease progression).

It is also important to note that the stratification of the results for both analyzes (progression-free and overall survivals) for potential confounding variables (T and N clinical stages and previous treatment modalities) did not alter the results, which means that complete pathological response was a better prognostic factor in patients with SCCO, regardless of other variables.

Discussion

This study identified that 52.6% of patients in IVa and IVb stage for squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx show complete pathological response after chemoradiotherapy, a finding similar to other studies. Dhiwakar et al.18 studied selective neck dissection in patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of several sites in the head and neck with partial response after chemoradiotherapy, including 39 cases (63%) of SCCO. These authors found cervical persistence in 32 neck dissection specimens (46%); 22 patients (35%) developed recurrent disease (seven at the primary site, 11 distant, and four cases in the neck, but only one ipsilateral case).

A study carried out at the Sloan-Kettering Memorial Cancer Center19 that evaluated planned neck dissection in 56 post-chemoradiotherapy patients with head and neck SCC (71% in the oropharynx) found that presence of a viable tumor in the cervical specimen was a predictor of lower overall (49%) and disease-free (56%) survival, as well as of lower recurrence-free (40%) survival, when compared to patients with complete cervical pathological response (93%, 93%, and 75%, respectively). The authors also reported that 63% of 19 patients with a viable tumor relapsed during follow-up; among these, eight cases also developed remote disease. Lango et al.20 found similar results, with 37% of progression-free survival in patients with a viable tumor in the cervical specimen vs. 85% in patients with complete pathological response, corroborating the prognostic significance of residual disease after chemoradiotherapy in these patients.

The present study also found that the presence of residual tumor in the cervical specimen obtained from planned neck dissection in SCCO patients treated with chemoradiotherapy was associated with lower overall survival and disease-free rates, regardless of other possible confounding variables–again a finding which is similar to those observed by other authors.2, 10, 11, 21 It should also be noted that the present study included 19 consecutive patients, which may at first be considered a limited sample; however, the power calculated for the main conducted estimates (differences in progression-free and overall survivals) exceeded 95%, showing statistical significance for these findings.

Krstevska et al.22 studied chemoradiotherapy as primary treatment in patients with III- and IV-stage SCCO and found that recurrence-free, disease-free, and overall survivals were 41.7%, 33.2%, and 49.7%, respectively. Clayman et al.23 also studied the influence of complete pathological response in the prognosis for patients with SCCO. Sixty-six patients with N2a stage or superior were submitted to platinum-based induction chemotherapy, followed by radiotherapy in isolation. Of these patients, 36% achieved complete clinical and radiological responses. Eighteen patients (17 with partial response and one case of complete response) underwent salvage neck dissection and 12 (56%) had evidence of residual disease. It is noteworthy that the only case of complete clinical response submitted to salvage surgery demonstrated microscopic disease in the neck dissection specimen. Low locoregional recurrence rate was also identified in patients with complete clinical response for their primary tumor after treatment. All patients requiring salvage neck dissection as well as resection of the primary tumor because of disease persistence suffered locoregional recurrence during follow-up–an enormous result when compared to patients not submitted to any rescue procedure (12%) or to those treated only with neck dissection (7%). In the same study, disease-free and overall survival rates were 49.2% and 78.4%, respectively, for the entire cohort. A significant increase was observed in overall survival specifically for patients undergoing salvage neck dissection (vs. those without nodal dissection) who achieved complete response in the primary site, but with partial response in the neck after chemoradiotherapy. The authors also recommend that patients with complete clinical or radiological response, and even those who had a bulky cervical disease, should only be monitored, without planned neck dissection, because none of the 29 patients with negative results by CT and magnetic resonance imaging suffered neck recurrence.

Returning to this subject, the literature suggests that, if there is clinical and radiological evidence of a complete locoregional response after chemoradiotherapy, the chance of residual cervical disease will be less than 20%.21 For these patients, positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG PET-CT) is the primary ancillary test to be used in a cervical assessment. Some studies advocate, as a principle, the use of dissection in these patients; but the most recent studies do not recommend neck dissection in N2- and N3-stage patients with evidence of clinical or imaging response (CT and/or 18-FDG PET-CT), considering the low residual disease rate and that a planned procedure would not lead to improvement in overall and disease-free survival rates. Thus, it is recommended that neck dissection is performed only as a rescue procedure.8, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Despite the literature evaluated, this study established that clinical response (assessed by physical examination, pan-endoscopy, and computed tomography) was not associated with complete pathologic response; therefore, a planned neck dissection could still be an indication in this patient group.

As demonstrated, some institutions and protocols argue that a 18-FDG PET-CT negative result for the neck is sufficient for an expectant management strategy. In theory, this would obviate the need for a planned neck dissection. However, a recently published study32 reviewed 243 cases of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck (70% of the oropharynx) submitted to PET-CT prior to their planned neck dissection (112 N0-clinical stage patients and 131 patients with a clinically positive neck). The authors found that the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy rates were, respectively, 57%, 82%, 59%, 80%, and 74% for N0-clinical stage patients; and 93%, 70%, 96%, 58%, and 91% for patients with evidence of lymph node disease. Thus, these authors concluded that PET/CT has low efficacy in detecting cervical metastases of N0-clinical stage patients, compared to individuals with a positive neck; and that the method is not beneficial for staging of N0-clinical stage patients, due to the high rates of false-positive and false-negative results. Another important point to be considered is the inaccessibility of this diagnostic modality in many oncology centers. This further underscores the importance of this study in determining the plan of treatment for this population. An expectant strategy can still be adopted in patients with complete clinical response after treatment, with good long-term disease-free survival rates.27

The diversity of treatment strategies found for these patients denotes the complexity of this subject. In addition, Javidnia and Corsten33 calculated the “number needed to treat” (NNT) in patients with advanced head and neck SCC (N2 and N3 stages) based on a systematic review of 15 studies with a total of 817 patients. The calculated NNT value was 7.5; i.e., to prevent one case of death from cervical recurrence after chemoradiotherapy, 7.5 cases of planned neck dissection should be performed, demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of the procedure.

Goguen et al.34 studied 105 neck dissection specimens after chemoradiotherapy, including 83 cases of SCCO (79%), and found that the presence of positive lymph nodes was significantly associated with a decrease in the progression-free survival, as well as in overall survival.

Cupino et al.35 specifically studied patients with stage IV SCCO submitted to selective (or even super-selective) dissection after chemoradiotherapy. The authors found rates of disease control of 95% and 88%, respectively, after two and three years of follow-up. No patient had cervical recurrence, with 91% remote disease-free survival after two years, and overall survival of 88% and 75% in two and three years of follow-up, respectively. Despite these significant oncological responses, the study is somewhat debatable, due to the heterogeneity of dissected cervical levels and the low number of cases. Esteller et al.36 included a diversified group of head and neck SCC, with 34.2% adjusted five-year overall survival rate after rescue surgery. In an earlier study,24 the same group found that N3-stage patients were at increased risk of cervical residual disease after chemoradiotherapy; and that N2-stage patients with complete response after treatment (evaluated by physical examination, neck CT, and PET-CT) did not require planned neck dissection, because such a procedure does not increase overall survival and disease-free rates.

Conclusion

The complete pathologic response after chemoradiotherapy positively influences the prognosis of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, with better rates of survival free of disease progression, as well as of overall survival – results similar to those found in the literature. However, more studies, especially with larger series, should be performed to establish a therapeutic guideline based on more consistent scientific evidence.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: Trufelli DC, de Matos LL, Santana TA, Capelli FA, Kanda JL, Del Giglio A, et al. Complete pathologic response as a prognostic factor for squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx post-chemoradiotherapy. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81:498–504.

References

- 1.Al-Sarraf M., LeBlanc M., Giri P.G., Fu K.K., Cooper J., Vuong T., et al. Chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: phase III randomized Intergroup study 0099. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1310–1317. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonner J.A., Harari P.M., Giralt J., Cohen R.B., Jones C.U., Sur R.K., et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denis F., Garaud P., Bardet E., Alfonsi M., Sire C., Germain T., et al. Final results of the 94-01 French Head and Neck Oncology and Radiotherapy Group randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone with concomitant radiochemotherapy in advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:69–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forastiere A.A., Goepfert H., Maor M., Pajak T.F., Weber R., Morrison W., et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribeiro Salles Vanni C.M., de Matos L.L., Faro Junior M.P., Ledo Kanda J., Cernea C.R., Garcia Brandao L., et al. Enhanced morbidity of pectoralis major myocutaneous flap used for salvage after previously failed oncological treatment and unsuccessful reconstructive head and neck surgery. Sci World J. 2012:2012384179. doi: 10.1100/2012/384179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinto F.R., Matos L.L., Gumz Segundo W., Vanni C.M., Rosa D.S., Kanda J.L. Tobacco and alcohol use after head and neck cancer treatment: influence of the type of oncological treatment employed. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2011;57:171–176. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302011000200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barkley H.T., Jr., Fletcher G.H., Jesse R.H., Lindberg R.D. Management of cervical lymph node metastases in squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsillar fossa, base of tongue, supraglottic larynx, and hypopharynx. Am J Surg. 1972;124:462–467. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(72)90067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamoir M., Ferlito A., Schmitz S., Hanin F.X., Thariat J., Weynand B., et al. The role of neck dissection in the setting of chemoradiation therapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with advanced neck disease. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bree R., van der Waal I., Doornaert P., Werner J.A., Castelijns J.A., Leemans C.R. Indications and extent of elective neck dissection in patients with early stage oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma: nationwide survey in The Netherlands. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:889–898. doi: 10.1017/S0022215109004800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendenhall W.M., Million R.R., Cassisi N.J. Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck treated with radiation therapy: the role of neck dissection for clinically positive neck nodes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12:733–740. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(86)90030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendenhall W.M., Villaret D.B., Amdur R.J., Hinerman R.W., Mancuso A.A. Planned neck dissection after definitive radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2002;24:1012–1018. doi: 10.1002/hed.10187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ensley J.F., Jacobs J.R., Weaver A., Kinzie J., Crissman J., Kish J.A., et al. Correlation between response to cisplatinum-combination chemotherapy and subsequent radiotherapy in previously untreated patients with advanced squamous cell cancers of the head and neck. Cancer. 1984;54:811–814. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840901)54:5<811::aid-cncr2820540508>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd T.S., Harari P.M., Tannehill S.P., Voytovich M.C., Hartig G.K., Ford C.N., et al. Planned postradiotherapy neck dissection in patients with advanced head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 1998;20:132–137. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199803)20:2<132::aid-hed6>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robbins K.T., Doweck I., Samant S., Vieira F. Effectiveness of superselective and selective neck dissection for advanced nodal metastases after chemoradiation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:965–969. doi: 10.1001/archotol.131.11.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavertu P., Adelstein D.J., Saxton J.P., Secic M., Wanamaker J.R., Eliachar I., et al. Management of the neck in a randomized trial comparing concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone in resectable stage III and IV squamous cell head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 1997;19:559–566. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199710)19:7<559::aid-hed1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon C., Goepfert H., Rosenthal D.I., Roberts D., El-Naggar A., Old M., et al. Presence of malignant tumor cells in persistent neck disease after radiotherapy for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx is associated with poor survival. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:313–318. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-1016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stenson K.M., Huo D., Blair E., Cohen E.E., Argiris A., Haraf D.J., et al. Planned post-chemoradiation neck dissection: significance of radiation dose. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:33–36. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000185846.27617.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhiwakar M., Robbins K.T., Vieira F., Rao K., Malone J. Selective neck dissection as an early salvage intervention for clinically persistent nodal disease following chemoradiation. Head Neck. 2012;34:188–193. doi: 10.1002/hed.21707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganly I., Bocker J., Carlson D.L., D’Arpa S., Coleman M., Lee N., et al. Viable tumor in postchemoradiation neck dissection specimens as an indicator of poor outcome. Head Neck. 2011;33:1387–1393. doi: 10.1002/hed.21612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lango M.N., Andrews G.A., Ahmad S., Feigenberg S., Tuluc M., Gaughan J., et al. Postradiotherapy neck dissection for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: pattern of pathologic residual carcinoma and prognosis. Head Neck. 2009;31:328–337. doi: 10.1002/hed.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellitteri P.K., Ferlito A., Rinaldo A., Shah J.P., Weber R.S., Lowry J., et al. Planned neck dissection following chemoradiotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer: is it necessary for all. Head Neck. 2006;28:166–175. doi: 10.1002/hed.20302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krstevska V., Stojkovski I., Zafirova-Ivanovska B. Concurrent radiochemotherapy in locally-regionally advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: analysis of treatment results and prognostic factors. Radiat Oncol. 2012:2012. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clayman G.L., Johnson C.J., 2nd, Morrison W., Ginsberg L., Lippman S.M. The role of neck dissection after chemoradiotherapy for oropharyngeal cancer with advanced nodal disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:135–139. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goguen L.A., Posner M.R., Tishler R.B., Wirth L.J., Norris C.M., Annino D.J., et al. Examining the need for neck dissection in the era of chemoradiation therapy for advanced head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:526–531. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.5.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang N.Y., Lee K.W., Ahn S.H., Kim J.S., Kim I.A. Neck control after definitive radiochemotherapy without planned neck dissection in node-positive head and neck cancers. BMC Cancer. 2012:2012. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lau H., Phan T., Mackinnon J., Matthews T.W. Absence of planned neck dissection for the N2–N3 neck after chemoradiation for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:257–261. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2007.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Da Mosto M.C., Lupato V., Romeo S., Spinato G., Addonisio G., Baggio V., et al. Is neck dissection necessary after induction plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy in complete responder head and neck cancer patients with pretherapy advanced nodal disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:250–256. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moukarbel R.V., Fung K., Venkatesan V., Franklin J.H., Pavamani S., Hammond A., et al. The N3 neck: outcomes following primary chemoradiotherapy. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;40:137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez Rodriguez M., Cerezo Padellano L., Martin Martin M., Counago Lorenzo F. Neck dissection after radiochemotherapy in patients with locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2008;10:812–816. doi: 10.1007/s12094-008-0294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soltys S.G., Choi C.Y., Fee W.E., Pinto H.A., Le Q.T. A planned neck dissection is not necessary in all patients with N2-3 head-and-neck cancer after sequential chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:994–999. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki M., Kawakita D., Hanai N., Hirakawa H., Ozawa T., Terada A., et al. The contribution of neck dissection for residual neck disease after chemoradiotherapy in advanced oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10147-012-0419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozer E., Naiboglu B., Meacham R., Ryoo C., Agrawal A., Schuller D.E. The value of PET/CT to assess clinically negative necks. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:2411–2414. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-1926-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Javidnia H., Corsten M.J. Number needed to treat analysis for planned neck dissection after chemoradiotherapy for advanced neck disease. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39:664–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goguen L.A., Chapuy C.I., Li Y., Zhao S.D., Annino D.J. Neck dissection after chemoradiotherapy: timing and complications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:1071–1077. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cupino A., Axelrod R., Anne P.R., Sidhu K., Lavarino J., Kung B., et al. Neck dissection followed by chemoradiotherapy for stage IV (N+) oropharynx cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:416–421. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esteller E., Vega M.C., Lopez M., Quer M., Leon X. Salvage surgery after locoregional failure in head and neck carcinoma patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:295–301. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]