Abstract

Introduction

The establishment of an individualized prognostic evaluation in patients with a diagnosis of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSHL) remains a difficult and imprecise task, due mostly to the variety of etiologies. Determining which variables have prognostic value in the initial assessment of the patient would be extremely useful in clinical practice.

Objective

To establish which variables identifiable at the onset of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss have prognostic value in the final hearing recovery.

Methods

Prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Patients with ISSHL followed by the Department of Otology-Neurotology of a quaternary hospital were included. The following variables were evaluated and correlated with final hearing recovery: age, gender, vertigo, tinnitus, initial degree of hearing loss, contralateral ear hearing, and elapsed time to treatment.

Results

127 patients with ISSHL were evaluated. Rates of absolute and relative recovery were 23.6 dB and 37.2% respectively. Complete hearing improvement was observed in 15.7% patients; 27.6% demonstrated significant improvement and improvement was noted in 57.5%.

Conclusion

During the onset of ISSHL, the following variables were correlated with a worse prognosis: dizziness, profound hearing loss, impaired hearing in the contralateral ear, and delay to start treatment. Tinnitus at the onset of ISSHL correlated with a better prognosis.

Keywords: Prognosis, Sudden hearing loss, Audiometry

Resumo

Introdução

Elaborar avaliação prognóstica individualizada em pacientes com diagnóstico de perda auditiva neurossensorial súbita idiopática (PANSI) permanece tarefa árdua e imprecisa devido, em grande parte, à variedade de etiologias. A determinação de quais variáveis teriam valor prognóstico na avaliação inicial do paciente seria de extrema utilidade na prática clínica.

Objetivo

Estabelecer quais variáveis, identificáveis no momento de instalação da perda auditiva neurossensorial súbita idiopática, têm valor prognóstico na recuperação auditiva final.

Método

Estudo de coorte prospectivo, longitudinal. Incluídos pacientes com PANSI acompanhados pela Disciplina de Otologia–Neurotologia de um hospital quaternário. As seguintes variáveis foram avaliadas e correlacionadas com a recuperação auditiva final: idade, gênero, vertigem, zumbido, grau de perda auditiva inicial, audição na orelha contralateral, tempo para início de tratamento.

Resultado

Foram avaliados 127 pacientes com PANSI. As taxas de recuperação absoluta e relativa foram 23,6 dB e 37,2% respectivamente. Apresentaram melhora completa da audição 15,7% dos pacientes; 27,6% apresentaram melhora significativa e 57,5% melhora.

Conclusão

No momento da instalação da PANSI, as seguintes variáveis correlacionaram-se com pior prognóstico: vertigem, perda auditiva profunda, audição alterada na orelha contralateral e demora para início do tratamento. Presença de zumbido na instalação da PANSI correlacionou-se com melhor prognóstico.

Palavras-chave: Prognóstico, Perda auditiva súbita, Audiometria

Introduction

Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSHL) is characterized by the occurrence of a hearing loss of at least 30 dB in three contiguous frequencies, with its onset in a period from a few hours up to three days.1 Despite being relatively common, with an incidence of 5–20 cases per 100,000 people per year,2 the physiopathogenesis of ISSHL remains to be clarified. A recurring drawback in ISSHL is a delay in its diagnosis and, due to a variety of etiologies, an individualized prognostic assessment remains difficult to establish, and is frequently inaccurate.

Several case series indicate that ISSHL typically occurs in patients aged 43–53 years, with no predilection for gender. Spontaneous recovery of hearing threshold is observed in about one-third to 65% of cases.1, 3 Despite the lack of consistent data on treatment of ISSHL, systemic corticosteroids have been used in clinical practice as the drug of choice.4, 5

Studies with a focus on prognostic factors have received limited attention and are usually neglected in lieu of research on treatment and etiology.6 Determining which variables would have prognostic value in an initial patient evaluation would be extremely useful in clinical practice, as it would allow an individual classification of patients according to the severity of each case, as well as the establishment of a more accurate prognosis for each individual, and defining which patients would be benefited with the use of corticosteroids. In addition, it would be possible to more precisely inform patients about the real chances of hearing recovery, in addition to avoid the use of corticosteroids – an often unnecessary therapy. Finally, it would strengthen the efforts to change the current paradigm of empirical treatment of ISSHL.

This study aims to establish which variables identifiable at the onset of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss have prognostic value in the final hearing recovery.

Methods

This was a prospective, longitudinal cohort study that included patients with ISSHL attended to at the Sudden Deafness Outpatient Clinic and followed-up by the Department of Otology-Neurotology at a quaternary hospital. This project was approved by the institution's Ethics Committee, under protocol 0715/11.

All patients were treated with prednisone 1 mg/kg/day (maximum daily dose = 60 mg) PO for at least a week. The dose was reduced weekly for up to 21 days. Those patients with contraindications to the use of this dosage of prednisone had their dose reduced; or, in some rare cases, replaced by deflazacort.

Patients with a history of middle and inner ear disease with a defined etiology such as trauma, infection, perilymphatic fistula, retrocochlear disease (schwannoma), degenerative disease of the central nervous system (multiple sclerosis), exposure to ototoxic drugs, barotrauma, middle or inner ear malformation, history suggestive of mumps, definite Ménière's disease, bilateral ISSHL cases, and patients who had the onset of monitoring not begin until 45 days after the onset of hearing loss were excluded from this study.

The hearing assessment of patients was performed with an MAICO MA-41 audiometer, and all tests were performed by the same speech therapist. The initial and final audiometric parameters were evaluated; the last evaluation was obtained two months after the initial audiometry, or before in those patients with a full recovery. In patients where the hearing thresholds of profound losses were not detected, the maximum audiometric limit was considered as the response (in this case, 120 dB).

In all patients, the means of initial and final pure tones were obtained, according to the group of frequencies affected. When low and medium tones were involved, the means of 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 kHz frequencies was calculated; when medium and high frequencies were affected, the means of 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 kHz frequencies were calculated; when only high frequency tones were involved, the means of 3, 4, 6, and 8 kHz frequencies were calculated; and finally when low, medium, and high frequencies were affected, the mean of all eight frequencies was calculated. Levels of 250 and 500 Hz; 1 and 2 kHz; and 3, 4, 6, and 8 kHz were considered low, medium, and high frequencies, respectively.

The following hearing recovery criteria were used:

-

•

Improvement: a change of functional category, and improvement of 15 dB.

-

•

Significant improvement: there was improvement, with a final hearing loss of mild intensity.

-

•

Full improvement: there was improvement, with hearing thresholds returning to normal (25 dB).

To calculate hearing recovery, Tucci et al.7 has suggested the use of audiometric thresholds for the unaffected ear as a baseline value, under the premise that there was a symmetrical hearing level before the ISSHL episode. For this calculation, the author took into account only the initial pure tone average (PTA) from the unaffected ear. However, in the present study used the initial and final PTA values for the unaffected side, with the objective of reducing both systematic and random errors, taking into account that the measures on the affected and unaffected sides were obtained at the same time. Therefore, PTA relative recovery was calculated using the following formula, in dB:

The calculation of PTA relative recovery (as a percentage) was carried out with the use of the following formula:

where PTAIA is the initial PTA of the affected ear; PTAINA is the initial PTA of the unaffected ear; PTAFA is the final PTA of the affected ear; and PTAFNA is the final PTA of the unaffected ear.

The following variables were evaluated and correlated with PTA recovery rates: age, gender, vertigo, tinnitus, initial degree of hearing loss, hearing in the contralateral ear, and time to onset of treatment.

In the statistical analysis, independent Student's t-tests were used when comparing two groups, and ANOVA (analysis of variance) tests were used when comparing three or more groups, considering a significance level of 5%.

Results

From 2000 to 2010, 277 patients with ISSHL were evaluated at the Sudden Deafness Outpatient Clinic. Of this total, eight patients did not meet the definition criteria for loss of at least 30 dB in at least three consecutive frequencies. In addition, ten cases were bilateral; and in 33 patients the cause of hearing loss was found. Seventy-five patients were lost to follow-up, and in 24 patients the informed consent was not obtained. Therefore, taking into account the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the final sample contained 127 patients.

The absolute and relative recovery rates were 23.6 dB and 37.2%, respectively. 15.7% of patients showed full improvement, 27.6% showed significant improvement, and 57.5% showed improvement.

The average age was 48 years (range 12–82 years). Table 1 shows PTA recovery rates in different age groups. 50.4% (n = 64) of patients were male, and 49.6% (n = 63) were female. PTA recovery rates between genders are included in Table 2.

Table 1.

ANOVA tests among age groups for recovery rates.

| Age group |

ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤30 | 31–50 | 51–70 | ≥71 | p | |

| Absolute PTA recovery | |||||

| Mean | 14.22 | 28.46 | 25.07 | 14.06 | |

| Standard deviation | 16.66 | 27.91 | 23.53 | 12.90 | 0.085 |

| n | 22 | 43 | 54 | 8 | |

| Relative PTA recovery | |||||

| Mean | 22.28% | 45.03% | 39.03% | 23.98% | |

| Standard deviation | 29.62% | 43.16% | 32.77% | 19.80% | 0.072 |

| n | 22 | 43 | 54 | 8 | |

PTA, pure tone average.

Table 2.

Independent Student's t-tests between genders for recovery rates.

| Gender |

t-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Patient | |

| Absolute PTA recovery | |||

| Mean | 24.06 | 23.23 | |

| Standard deviation | 25.01 | 23.22 | 0.847 |

| n | 64 | 63 | |

| Relative PTA recovery | |||

| Mean | 36.74 | 37.70 | |

| Standard deviation | 35.57 | 37.18 | 0.882 |

| n | 64 | 63 | |

PTA, pure tone average.

Tinnitus occurred in 92.1% (n = 117) of cases. PTA recovery rates for those with and without symptoms are shown in Table 3. Vertigo was present in 52.8% (n = 67) of cases. PTA recovery rates were compared between patients with and without this symptom, as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Independent Student's t-tests between presence and absence of tinnitus for recovery rates.

| Tinnitus |

t-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | |

| Absolute PTA recovery | |||

| Mean | 5.81 | 25.17 | |

| Standard deviation | 17.07 | 23.99 | 0.014 |

| n | 10 | 117 | |

| Relative PTA recovery | |||

| Mean | 13.44% | 39.25% | |

| Standard deviation | 41.63% | 35.20% | 0.030 |

| n | 64 | 63 | |

PTA, pure tone average.

Table 4.

Independent Student's t-tests between presence and absence of vertigo for recovery rates.

| Vertigo |

t-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | |

| Absolute PTA recovery | |||

| Mean | 25.83 | 21.70 | |

| Standard deviation | 26.01 | 22.16 | 0.330 |

| n | 60 | 67 | |

| Relative PTA recovery | |||

| Mean | 47.69% | 27.83% | |

| Standard deviation | 42.44% | 26.60% | 0.002 |

| n | 60 | 67 | |

PTA, pure tone average.

The results shown in Table 5 compare the degree of the initial hearing loss with PTA recovery rates.

Table 5.

ANOVA tests among grades of initial loss for recovery rates.

| Grade of initial loss |

ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Severe | Profound | p | |

| Absolute PTA recovery | ||||

| Mean | 20.29 | 23.60 | 25.88 | |

| Standard deviation | 17.45 | 25.20 | 27.59 | 0.546 |

| n | 34 | 37 | 52 | |

| Relative PTA recovery | ||||

| Mean | 48.21% | 34.79% | 28.76% | |

| Standard deviation | 38.25% | 37.10% | 31.81% | 0.046 |

| n | 34 | 37 | 52 | |

PTA, pure tone average.

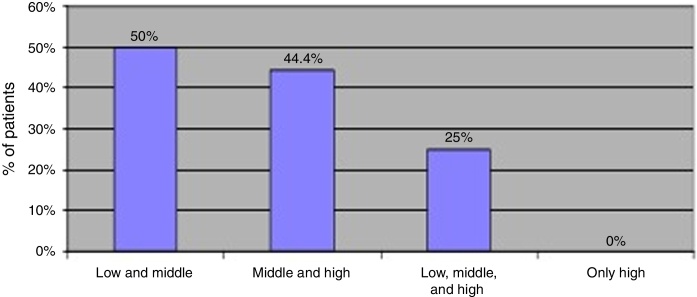

Fig. 1 shows the percentages of patients achieving significant improvement in their hearing acuity, separated by groups of affected frequencies.

Figure 1.

Distribution of significant hearing recovery percentage by groups of affected frequencies.

Contralateral ear hearing involvement was compared vs. individuals without hearing alteration in their contralateral ear, and the results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Independent Student's t-tests between contralateral ear hearing states for recovery rates.

| Contralateral ear |

t-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Changed | p | |

| Absolute PTA recovery | |||

| Mean | 25.70 | 11.22 | |

| Standard deviation | 24.02 | 20.73 | 0.017 |

| n | 109 | 18 | |

| Relative PTA recovery | |||

| Mean | 39.78% | 21.67% | |

| Standard deviation | 34.41% | 43.73% | 0.049 |

| n | 109 | 18 | |

PTA, pure tone average.

The time elapsed to treatment, at different times, and their respective correlation with PTA recovery, are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

ANOVA tests among groups for time elapsed to treatment and recovery rates.

| Time elapsed to treatment |

ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2 days | 2–7 days | 8–10 days | >10 days | p | |

| Absolute PTA recovery | |||||

| Mean | 33.98 | 29.85 | 24.02 | 18.35 | |

| Standard deviation | 23.08 | 24.57 | 15.17 | 27.51 | 0.008 |

| n | 21 | 38 | 11 | 29 | |

| Relative PTA recovery | |||||

| Mean | 50.07% | 48.51% | 44.60% | 24.49% | |

| Standard deviation | 31.33% | 39.27% | 27.55% | 34.35% | 0.004 |

| n | 21 | 38 | 11 | 29 | |

PTA, pure tone average.

Discussion

The word “prognosis”, etymologically derived from the Greek, means “to know beforehand.” Established as a key concept of medicine by Hippocrates,8 the act of prognostication only is justified if based – in a necessary and mandatory way – on a sufficient medical diagnosis. An apocryphal phrase teaches: “Therefore, there is no credible prognosis without diagnosis.”

Thus, a challenge arises in determining the prognosis of a disease like ISSHL that, by definition, is an idiopathic event. In fact, ISSHL would be better labeled as a symptom common to multiple diseases and, therefore, with different etiologies – and for each etiology, with a respective prognosis. The interpretation and comparison of studies on prognostic factors in patients with ISSHL still constitute a difficult and imprecise task, and there is no consensus regarding the actual influence of the factors studied in the clinical outcome of patients. Several prognostic factors have been studied in recent decades, with inconsistent results regarding the individual influence of each factor.2, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

In the present study, there was no statistically significant difference for improvement of PTA recovery rates in those different age groups studied. However, there was a trend of a better performance in age groups of 31–50 and 51–70 years. In extreme ages, absolute and relative recovery rates were lower than those for the global sample. A well designed eight-year prospective study found similar results, with poorer hearing recovery in patients aged under 15 years and above 60 years; that study attributed these findings to a vulnerability of the immune system, peculiar to extremes of age, as a probable explanation.2 Nakashima et al. 17 found higher rates of profound losses in children under 14 years. Several studies consider older age as a poor prognosis factor for hearing recovery.11, 13, 18, 19, 20 It is postulated that the cellular degeneration inherent to the natural process of aging, in association with a reduced capacity for metabolic and cellular regeneration, have a negative influence.13 Other studies, however, found no such correlation.10, 12, 14

No correlation was found between gender and hearing recovery degree in this study, confirming the findings of other publications.13, 19, 21

Tinnitus was present in 92.1% of patients, a very high prevalence. This group of patients had statistically significant higher rates of absolute and relative recovery compared to the group without tinnitus, corroborating previous studies.10, 22, 23 It is assumed that presence of tinnitus after cochlear injury would indicate that hair cells remain viable.24

Vertigo was present in 52.8% of subjects, who showed lower relative recovery rates compared to the group without this symptom (p = 0.002). It is well-established that vertigo is a factor for worse prognosis.2, 3, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 18, 22, 23, 25 A study analyzing 13 patients diagnosed with ISSHL with and without vertigo revealed that those with losses in high frequencies showed better recovery in the absence of vertigo.17 The authors concluded that the inflammatory response located in the basal region of the cochlea could overcome the barriers of the anterior labyrinth, reach the vestibule and semicircular canals and trigger vestibular symptoms.

The relative recovery rate was higher for patients with moderate vs. profound loss, with statistical significance difference. Many studies consider the initial degree of hearing loss as an important prognostic factor. In patients with a pronounced initial hearing loss, the worst audiological result is expected at the end of follow-up.2, 3, 9, 10, 20, 22 It is believed that in cases of profound loss, the extent of hair cell injury is so extensive, it does not allow a significant structural and functional recovery.

With the individualization of hearing recovery by group of affected frequencies, it was noted that high frequencies, when viewed in isolation, were not accompanied by a significant hearing recovery (Fig. 1), while the low- and middle-frequency groups achieved better results. It should be borne in mind that most studies do not include this differentiation by frequency, a fact which certainly compromises the analysis of results. It is estimated that about one-third to 65% of cases of ISSHL achieve spontaneous hearing recovery,1, 3 but the parameters used to measure such improvement are, as a rule, speech reception threshold (SRT), speech recognition threshold index (SRTI), and PTA, which do not cover higher frequencies, especially 6 and 8 kHz.

Subjects with normal contralateral hearing showed absolute and relative recovery rates higher than those with altered contralateral hearing, with statistically significant difference for both rates. Previous studies with larger samples also concluded that altered contralateral hearing is associated with a worse prognosis.2, 10 It is believed that this change indicates some pre-existing dysfunction of the auditory system, or of other systems of the body, that reduces the potential for recovery.

Patients who started their treatment before seven days had higher rates of absolute and relative recovery compared to patients included in the categories above seven and ten days (p = 0.008), a result similar to several other studies.10, 12, 13, 14, 18, 19, 25 There was no statistically significant difference in recovery rates among patients who started their treatment within 48 h and up to seven days, suggesting that treatment with corticosteroids has the same effectiveness, if started within seven days. In a study of 347 subjects, no benefit was noted with an early onset of treatment, comparing patients who started corticosteroids within two days or between three and seven days.26

Conclusion

At the time of ISSHL onset, the following variables correlated with a worse prognosis: dizziness, profound hearing loss, change in contralateral ear hearing, and a delayed start of treatment. Presence of tinnitus at ISSHL onset correlated with a better prognosis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: Bogaz EA, Maranhao ASA, Inoue DP, Suzuki FAB, Penido NO. Variables with prognostic value in the onset of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. 2015;81:520–6.

Institution: Department of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP-EPM), São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Wilson W.R., Byl F.M., Laird N. The efficacy of steroids in the treatment of idiopathic sudden hearing loss. A double blind clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106:772–776. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1980.00790360050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byl F.M., Jr. Sudden hearing loss: eight years experience and suggested prognostic table. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:647–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattox D.E., Simmons F.B. Natural history of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:463–480. doi: 10.1177/000348947708600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conlin A.E., Parnes L.S. Treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:582–586. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stachler R.J., Chandrasekhar S.S., Archer S.M., Rosenfeld R.M., Schwartz S.R., Barrs D.M., et al. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg. 2012;146:S1. doi: 10.1177/0194599812436449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royston P., Moons K.G.M., Altman D.G., Vergouwe Y. Prognosis and prognostic research: developing a prognostic model. BMJ. 2009;338:b604. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tucci D.L., Farmer J.C., Jr., Kitch R.D., Witsell D.L. Treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss with systemic steroids and valacyclovir. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:301–308. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams F., editor. The genuine works of Hippocrates. Wilkins and Wilkins; Baltimore: 1939. Hippocrates on airs, waters and places. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceylan A., Celenk F., Kemaloglu Y.K., Bayazit Y.A., Goksu N., Ozbilen S. Impact of prognostic factors on recovery from sudden hearing loss. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:1035–1040. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107005683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cvorovic L., Deric D., Probst R., Hegemann S. Prognostic model for predicting hearing recovery in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29:464–469. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31816fdcb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki H., Mori T., Hashida K., Shibata M., Nguyen K.H., Wakasugi T., et al. Prediction model for hearing outcome in patients with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:497–500. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xenellis J., Karapatsas I., Papadimitriou N., Nikolopoulos T., Maragoudakis P., Tzagkaroulakis M., et al. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: prognostic Factors. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:718–724. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106002362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang N.C., Kuen-Yao Ho M.D., Kuo W.R. Audiometric patterns prognosis in sudden sensorineural hearing loss in Southern Taiwan. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:916–922. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mamak A., Yilmaz S., Cansiz H., Inci E., Guclu E., Derekoylu L. A study of prognostic factors in sudden hearing loss. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005;84:641–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagaoka J., Anjos M.F., Takata T.T., Chaim R.M., Barros F.A., Penido N.O. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: evolution in the presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76:363–369. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942010000300015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penido N.O., Ramos H.V.L., Barros F.A., Cruz O.L.M., Toledo R.N. Fatores clínicos, etiológicos e evolutivos da audição na surdez súbita. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71:633–638. doi: 10.1016/s1808-8694(15)31268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakashima T., Yanagita N. Outcome of sudden deafness with and without vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:1145–1149. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byl F.M. Seventy-six cases of presumed sudden hearing loss: prognosis and incidence. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:817–825. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540870515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nosrati-Zarenoe R., Arlinger S., Hultcrantz E. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: results drawn from the Swedish national database. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 2007;127:1168–1175. doi: 10.1080/00016480701242477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laird N., Wilson W.R. Predicting recovery from idiopathic sudden hearing loss. Am J Otolaryngol. 1983;4:161–165. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(83)80038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samim E., Kilic R., Ozdek A., Gocman H., Eryilmaz A., Unlu I. Combined treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss with steroid, dextran and piracetam: experience with 68 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:187–190. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0659-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saeki N., Kitahara M. Assessment of prognosis in sudden deafness. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1994:S56–S61. doi: 10.3109/00016489409127304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park H.M., Jung S.W., Rhee C.K. Vestibular diagnosis as prognostic indicator in sudden hearing loss with vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 2001:S80–S83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danino J., Joachims H.Z., Eliachar I., Podoshin L., Ben-David Y., Fradis M. Tinnitus as a prognostic factor in sudden deafness. Am J Otolaryngol. 1984;5:394–396. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(84)80054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaia F.T., Sheehy J.L. Sudden sensori-neural hearing impairment: a report of 1220 cases. Laryngoscope. 1976;86:389–398. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197603000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huy P.T., Sauvaget E. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss is not an otologic emergency. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:896–902. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000185071.35328.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]