Abstract

Introduction

Human papillomavirus has been associated with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. However, there is no conclusive evidence on the prevalence of oral or pharyngeal infection by human papillomavirus in the Brazilian population.

Objective

To determine the rate of human papillomavirus infection in the Brazilian population.

Methods

Systematic review of published articles. Medline, The Cochrane Library, Embase, Lilacs (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences) and Scielo electronic databases were searched. The search included published articles up to December 2014 in Portuguese, Spanish and English. A wide search strategy was employed in order to avoid publication biases and to assess studies dealing only with oral and/or oropharyngeal human papillomavirus infections in the Brazilian population.

Results

The 42 selected articles enrolled 4066 patients. It was observed that oral or oropharyngeal human papillomavirus infections were identified in 738 patients (18.2%; IC 95 17.6–18.8), varying between 0.0% and 91.9%. The prevalences of oral or oropharyngeal human papillomavirus infections were respectively 6.2%, 44.6%, 44.4%, 27.4%, 38.5% and 11.9% for healthy people, those with benign oral lesions, pre-malignant lesions, oral or oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, risk groups (patients with genital human papillomavirus lesions or infected partners) and immunocompromised patients. The risk of human papillomavirus infection was estimated for each subgroup and it was evident that, when compared to the healthy population, the risk of human papillomavirus infection was approximately 1.5–9.0 times higher, especially in patients with an immunodeficiency, oral lesions and squamous cell carcinoma. The rates of the most well-known oncogenic types (human papillomavirus 16 and/or 18) also show this increased risk.

Conclusions

Globally, the Brazilian healthy population has a very low oral human papillomavirus infection rate. Other groups, such as at-risk patients or their partners, immunocompromised patients, people with oral lesions and patients with oral cavity or oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma have a high risk of human papillomavirus infection.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, Oropharynx, Mouth, Brazil, Prevalence

Resumo

Introdução

O papilomavírus humano (HPV) tem sido associado ao carcinoma de células escamosas (CCE) de cabeça e pescoço. No entanto, não existem evidências conclusivas sobre a prevalência de infecção oral ou faríngea pelo HPV na população brasileira.

Objetivo

Determinar a taxa de infecção pelo HPV na população brasileira.

Método

Revisão sistemática de artigos publicados. Foram feitas buscas nos seguintes bancos de dados eletrônicos: Medline, The Cochrane Library, Embase, Lilacs (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences) e Scielo. A busca considerou artigos publicados até dezembro de 2014, em português, espanhol e inglês. Foi utilizada uma ampla estratégia de busca com o intuito de evitar viés de publicação e também para que fossem avaliados estudos que tratassem apenas de infecções orais e/ou orofaríngeas pelo HPV na população brasileira.

Resultados

Os 42 artigos selecionados incluíram 4.066 pacientes. Observou-se que infecções orais ou orofaríngeas pelo HPV foram identificadas em 738 pacientes (18,2%; IC95 17,6-18,8), variando entre 0,0-91,9%. As prevalências de infecções orais ou orofaríngeas pelo HPV foram, respectivamente, 6,2%, 44,6%, 44,4%, 27,4%, 38,5% e 11,9% em pacientes saudáveis, com lesões orais benignas, com lesões pré-malignas, com CCE oral ou orofaríngeo, grupos de risco (pacientes com lesões genitais pelo HPV ou parceiros infectados) e pacientes imunodeficientes. O risco de infecção pelo HPV foi estimado para cada subgrupo, quando ficou evidente que, em comparação com a população saudável, o risco de infecção por HPV foi aproximadamente 1,5-9,0 vezes mais alto, especialmente em pacientes com imunodeficiência, lesões orais e CCE. Os percentuais dos tipos oncogênicos mais conhecidos (HPV 16 e/ou 18) também mostram esse aumento no risco.

Conclusões

A população brasileira saudável apresenta taxa de infecção oral pelo HPV muito baixa. Outros grupos, por exemplo, pacientes de risco ou seus parceiros, pacientes imunodeficientes, indivíduos portadores de lesões orais e pacientes com CCE de cavidade oral ou orofaringe apresentam maior risco de infecção pelo HPV.

Palavras-chave: Papilomavírus humano, Orofaringe, Boca, Brasil, Prevalência

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common causes of sexually transmitted infections. HPV is classified as high-risk (or oncogenic), which is associated with malignancies, or low-risk (or non-oncogenic), which is related to benign diseases.1 The relationship between HPV infections, especially types 16 and 18, and anogenital cancer is well established. In the last decade, relationships between HPV and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) have been established, especially in younger patients without the classic risk factors (tobacco and alcohol abuse).2

The incidence of HNSCC is increasing worldwide, including in Brazil, and the role of HPV infection in its carcinogenesis might explain the trend.3 A previously published meta-analysis conducted in the 1990s with 4680 samples identified an HPV infection prevalence of 10.0% in normal mucosa, which was significantly less than for leukoplakia (22.2%) and oral SCC (46.5%).4 However, there is no conclusive evidence regarding the prevalence of oral or pharyngeal HPV infections in the Brazilian population. Existing studies resort to various methods, either in sampling or in the detection of HPV, eventually producing discrepant results.5

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine the rate of HPV infection in the Brazilian population based on a systematic review of published articles.

Methods

Ethics

The present study was not submitted to IRB because it was a systematic review exclusively with published articles.

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

Two authors performed searches of MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library, Embase, LILACS, and SciELO electronic databases. The search included published articles up to December of 2014 in Portuguese, Spanish, and English. A wide search strategy was employed in order to avoid publication biases and to assess studies dealing only with oral and/or oropharyngeal HPV infections in the Brazilian population. The following Medical Subject Headings and keywords were used: “human papillomavirus” and “Brazil” and “mouth” OR “human papillomavirus” and “Brazil” and “oropharynx”. Reference lists of previously obtained articles were also analyzed manually so that other relevant studies could be identified for inclusion in the present study.

Exclusion criteria

Articles that were not published in Portuguese, Spanish, or English, or where the full text could not be obtained, were excluded from the search. Articles that had no data or insufficient data regarding HPV statuses were also excluded. Articles from the same institution by the same set of authors were screened for study time-period overlaps, and if repetitive information was presented, duplicated data were excluded and data from the most complete data set were analyzed. Other exclusion criteria were: articles that included only patients who tested positive for oral or oropharyngeal HPV; articles based on a pediatric population, animals, or cell lines; review articles, case reports, or case series studies; HPV in sites other than the mouth and/or oropharynx; articles that did not study HPV; and studies with populations other than Brazilians or multicentric studies in which it was not possible to separate the Brazilian population's HPV status.

Data extraction

All data were extracted by two independent authors using a data recording form developed for this purpose, which included the following: city and state, population characteristics, dates when the sample was obtained, the type of material collected (paraffin-embedded, fresh tissue, and/or brushing mucosa) and subsite (mouth and/or oropharynx), age, smoking status, alcohol intake, gender, technology used for HPV detection (polymerase chain reaction [PCR], in situ hybridization, and/or immunohistochemistry [IHC]), and general and specific HPV status (HPV 16 and/or HPV 18). Any discrepancies were addressed following discussion and consensus between the two authors.

Data analysis

The articles were initially organized in the following groups to facilitate the analysis: (1) oral or oropharyngeal HPV infection in healthy patients; (2) oral or oropharyngeal HPV infection in patients with benign or premalignant lesions; (3) HPV infections in the oral cavity and/or oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); (4) oral or oropharyngeal HPV infection where patients or patients’ partners had genital HPV infections; (5) oral or oropharyngeal HPV infection in immunodeficient patients.

For the statistical analysis, the HPV status data were categorized into the following groups: healthy patients, immunodeficient patients, high-risk patients (those with genital HPV infections or infected partners), patients with benign lesions, with premalignant lesions (dysplasia, leukoplakia or erythroplakia), and with squamous cell carcinoma (oral cavity or oropharyngeal SCC). Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp® – Redmond, WA, United States) was used to tabulate data and to perform weighted average, frequency, and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) calculations. SPSS® version 17.0 (SPSS® Inc – Illinois, United States) was used for logistic regressions to assess the risk of HPV infection in each group, calculating odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs. In all of these analyses, the probability of making an α or type I error was considered as less than 5% (p < 0.05).

Results

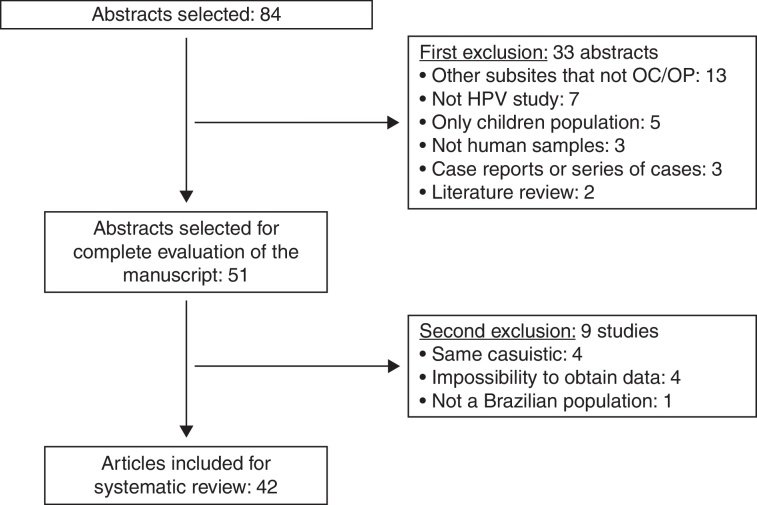

Using the established search strategy and inclusion criteria, 84 abstracts were identified (Fig. 1). Exclusion criteria included: studies with subsites other than the mouth or oropharynx (13), articles without HPV studies (seven), studies of pediatric populations (five), casuistic studies (four), unobtainable data (four), non-human samples (three), case reports or series of cases studies (three), review articles (two), and studies of non-Brazilian populations (one). Based on the criteria, 42 articles5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 were included in the systematic review (Table 1), and it was noted that the great majority of the studies were conducted in the last decade, with oral samples.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of article selection.

Table 1.

Demographic data of populations and samples collected in the included studies.

| Article | Brazilian city, state | Population characteristics | Sample date | Collected material | Subsite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in healthy patients | |||||

| Sacramento (2006)6 | São José do Rio Preto, SP | 50 healthy patients | 2006 | Fresh tissue | Oropharynx |

| Esquenazi (2010)7 | Rio de Janeiro, RJ | 100 healthy university students | 2006–2007 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Horewicz (2010)8 | Campinas, SP | 104 patients with gingival disorders and healthy mucosa | 2006–2009 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Tristão (2012)9 | Araras, SP | 125 healthy patients | 2007–2012 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Kreimer (2013)10 | São Paulo, SP | 499 healthy men | 2007–2013 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Cavenaghi (2013)5 | Votuporanga, SP | 124 healthy patients | 2011 | Brushing | Mouth and oropharynx |

| Araujo (2014)11 | Belém, PA | 166 healthy patients | 2014 | Brushing | Mouth and oropharynx |

| Machado (2014)12 | Campo Grande, MS | 514 healthy men | 2014 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in patients with benign or premalignant lesions | |||||

| Betiol (2012)13 | Araras, SP | 16 healthy patients and 8 cases of leukoplakia | 2010–2012 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Fonseca-Silva (2012)14 | Montes Claros, MG | 24 normal mucosa samples and 48 oral dysplasia lesions | Institutional archive | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| HPV infection in oral cavity and/or oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients | |||||

| Comparative studies (healthy people versus SCC patients) | |||||

| Cortezzi (2004)15 | São José do Rio Preto and São Paulo, SP | 16 SCC and 142 healthy patients | 2004 | Fresh tissue (SCC) Brushing (healthy) |

Mouth and oropharynx |

| Silva (2007)16 | São Paulo, SP | 50 SCC and 10 healthy volunteers | 2007 | Fresh tissue | Mouth |

| Mazon (2011)17 | Araraquara, SP | 18 benign lesions, 18 premalignant lesions, and 19 SCC | Institutional archive | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Comparative studies (benign lesions versus SCC patients) | |||||

| Soares (2002)18 | Araraquara, SP | 20 cases of benign oral lesions and 10 SCC | 1992–1998 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Soares (2003)19 | Araraquara, SP | 30 benign lesions and 27 SCC | Institutional archive | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Fregonesi (2003)20 | Araraquara, SP | 19 benign lesions, 10 premalignant lesions and 17 SCC | Institutional archive | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Acay (2008)21 | São Paulo, SP | 40 leukoplakia and 10 SCC | Institutional archive | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Lira (2010)22 | Ribeirão Preto-SP | 16 non-malignant oral lesions and 20 in situ SCC and 50 SCC | 2009 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Fregonezi (2012)23 | Ribeirão Preto, SP | 19 benign oral lesions, 16 premalignant oral lesions and 17 SCC | 1992–2005 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | |

| Populational studies | |||||

| Miguel (1998)24 | São Paulo, SP | 28 SCC | 1995–1996 | Fresh tissue | Mouth and oropharynx |

| Soares (2007)25 | Natal, RN | 75 SCC | 2000–2003 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Oliveira (2008)26 | Ribeirão Preto, SP | 87 SCC | Institutional archive | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Simonato (2008)27 | Araçatuba, SP | 29 SCC | 1991–2005 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Soares (2008)28 | Natal, RN | 33 SCC | 1996–2004 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Oliveira (2009)29 | Natal, RN | 88 SCC | 1996–2004 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Pereira (2011)30 | Natal, RN | 27 SCC | Institutional archive | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Spindula-Filho (2011)31 | Goiânia, GO | 39 SCC and 8 verrucous carcinoma | 2010 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Cordeiro-Silva (2012)32 | Vitória, ES and Goiânia, GO | 45 SCC | 2012 | Paraffin and fresh tissue | Mouth and oropharynx |

| Kaminagakura (2012)33 | São Paulo, SP | 114 SCC | 1970–2006 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth |

| Marques-Silva (2012)34 | Montes Claros, MG | 40 SCC | 1996–2007 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth and oropharynx |

| Cantarutti (2014)35 | Brasilia, DF | 26 SCC | 2005–2011 | Paraffin-embedded tissue | Mouth and oropharynx |

| Lopez (2014)36 | Goiânia, GO; Rio de Janeiro, RJ; São Paulo, SP; Ribeirão Preto, SP | 222 SCC | 1998–2008 | Paraffin-embedded and fresh tissue | Mouth and oropharynx |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in patients with genital HPV infection | |||||

| Comparative studies (healthy people versus patients with genital HPV infection) | |||||

| Gonçalves (2006)37 | Campinas, SP | 70 women with genital HPV infection and 70 healthy women | 2001–2002 | Saliva | Mouth |

| Marques (2013)38 | Brasilia, DF | 43 women with NIC lesions and 21 partners | 2011 | Brushing | Mouth and oropharynx |

| Ribeiro (2014)39 | Recife, PE | 31 married couples: men with penis squamous cell carcinoma or precursor lesions and their partners | 2006–2007 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Vidotti (2014)40 | São Luis, MA | 105 women with genital lesions clinically suspected for HPV infection | 2011–2012 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Populational studies | |||||

| Castro (2009)41 | Maceió, AL | 30 women with genital HPV infection | 2005–2006 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Xavier (2009)42 | São Paulo, SP | 30 men with anogenital HPV infection | 2009 | Brushing and fresh tissue | Mouth |

| Peixoto (2011)43 | Salvador, BA | 100 women with genital lesions confirmed for HPV infection | 2011 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Zonta (2012)44 | São Paulo, SP | 27 women from prison with pre-malignant or malignant lesions of the uterine cervix | 2012 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in immunodeficient patients (all comparative studies with healthy patients) | |||||

| Araujo (2011)45 | Curitiba, PR | 60 patients with Fanconi's anemia and severe anaplastic anemia and 16 healthy control | 2011 | Brushing | Mouth |

| Lima (2014)46 | São Paulo, SP | 100 women with HIV and 100 healthy women | 2013 | Brushing | Mouth |

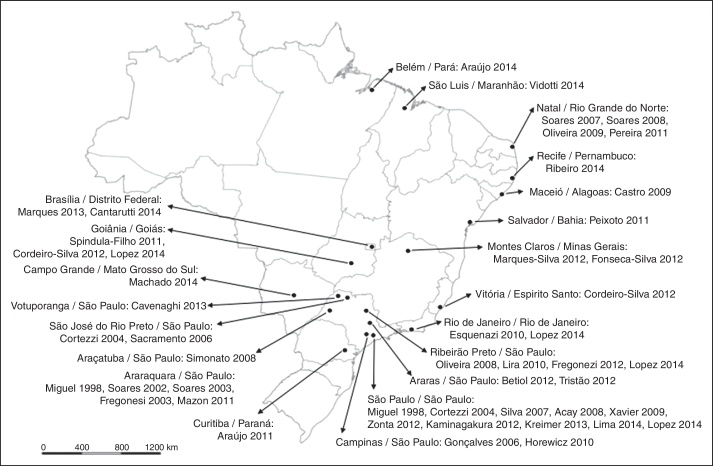

Brazil is a large country with a population of approximately 200,000,000. The articles analyzed came from all over the country, with concentrations in state capitals and more developed regions (for example, the Southeast Region, which had 61.9% of the studies, especially São Paulo State) as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Article distribution according to Brazilian city and state.

Demographic data

Eight articles (19%) studied oral or oropharyngeal HPV infection in healthy patients, two (4.8%) exclusively analyzed HPV status of patients with benign or premalignant oral lesions, 22 (52.4%) analyzed SCC patients (comparative or population studies), eight (19%) specifically studied oral or oropharyngeal HPV infections in patients with genital HPV infections or lesions or with infected partners, and two (4.8%) studied immunodeficient patients (Fanconi's anemia and HIV patients).

Thirty-four articles (80.9%) included demographic data, which are displayed in Table 2. It was observed that the weighted average for age was higher in the SCC group (59 years old) than the others (30–36 years old). Tobacco use and alcohol intake were similarly higher in these patients.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients of the included studies (when obtained from original article).

| Article | Age | Smoking status (%) | Alcohol intake (%) | Men/women |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in healthy patients | ||||

| Sacramento (2006)6 | Mean of 25 y | 14.3% | 71.4% | 21/29 |

| Esquenazi (2010)7 | Mean of 23 y | 3.0% | 3.0% | 40/60 |

| Horewicz (2010)8 | Mean of 38 y | 3.8% | – | 28/76 |

| Tristão (2012)9 | Predominantly between 18 and 21 y | – | – | 37/88 |

| Kreimer (2013)10 | 47% under 30 y 83% under 44 y |

40.0% | 74.0% | 499/0 |

| Cavenaghi (2013)5 | Mean of 51 y | 75.0% | 37.1% | 77/47 |

| Araujo (2014)11 | Mean of 36 y | 6.6% | 23.5% | 63/103 |

| Machado (2014)12 | Mean of 23 y | – | – | 0/514 |

| Weighted average | 30 years | 318/1043 (30.5%) | 493/939 (52.5%) | – |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in patients with benign or premalignant lesions | ||||

| Fonseca-Silva (2012)14 | Means: 32 y (control); 54 y (dysplasia) | 56.9% | 61.1% | 39/33 |

| HPV infection in oral cavity and/or oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients | ||||

| Comparative studies (healthy people versus SCC patients) | ||||

| Cortezzi (2004)15 | Mean of 61 y | – | – | 106/52 |

| Silva (2007)16 | Over 40 y | 100.0% | – | – |

| Comparative studies (benign lesions versus SCC patients) | ||||

| Lira (2010)22 | Mean of 57 y | 80.2% | 66.3% | 71/15 |

| Population studies | ||||

| Miguel (1998)24 | Mean of 61 y | 90.5% | – | 42/3 |

| Soares (2007)25 | Mean of 65 y | – | – | 49/26 |

| Oliveira (2008)26 | Mean of 59 y | 81.6% | – | 73/14 |

| Simonato (2008)27 | 79.3% under 60 y | 89.7% | 62.1% | 27/2 |

| Soares (2008)28 | Mean of 65 y | – | – | – |

| Oliveira (2009)29 | 59% over 60 y | – | – | 57/31 |

| Pereira (2011)30 | Mean of 63 y | – | – | 19/8 |

| Spindula-Filho (2011)31 | 55.3% over 65 y | 72.3% | 61.7% | 34/13 |

| Cordeiro-Silva (2012)32 | 44.5% over 58 y | 80.0% | 68.9% | 35/10 |

| Kaminagakura (2012)33 | Mean of 51 y | 84.0% | 62.0% | 81/33 |

| Marques-Silva (2012)34 | 33.3% under 45 y | 96.0% | 93.3% | 34/6 |

| Cantarutti (2014)35 | Mean of 56 y | 92.0% | 65.0% | 16/10 |

| Lopez (2014)36 | 45% under 55 y | 93.7% | 95.6% | – |

| Weighted average | 59 years | 703/801 (87.8%) | 458/609 (75.2%) | – |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in patients with genital HPV infection | ||||

| Comparative studies (healthy people versus patients with genital HPV infection) | ||||

| Gonçalves (2006)37 | Mean of 30 y | 29.3% | – | 0/140 |

| Marques (2013)38 | Mean of 45 y | – | – | 21/43 |

| Ribeiro (2014)39 | Mean of 32 y | 27.4% | – | 31/31 |

| Vidotti (2014)40 | 41.9% under 30 y | 7.6% | 33.3% | 0/105 |

| Population studies | ||||

| Castro (2009)41 | Mean of 28 y | 30.0% | 0.0% | 0/30 |

| Xavier (2009)42 | Mean of 29 y | – | – | 30/0 |

| Peixoto (2011)43 | Mean of 30 y | 15.0% | 88.1% | 0/100 |

| Zonta (2012)44 | 74.1% under 35 y | 66.7% | – | 0/27 |

| Weighted average | 32 years | 90/437 (20.6%) | 123/235 (52.3%) | – |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in immunodeficient patients (all comparative studies with healthy people) | ||||

| Lima (2014)46 | Mean of 36 y | 31.0% | 50.0% | 0/200 |

| Weighted average | 36 years | 62/200 (31.0%) | 100/200 (50.0%) | – |

Oral/oropharyngeal HPV status

The 42 articles included 4066 enrolled patients. It was observed that oral or oropharyngeal HPV infections were identified in 738 patients (18.2%; 95% CI 17.6%–18.8%), varying between 0.0% and 91.9%. HPV status was assessed using PCR in 90.5% of the studies and by in situ hybridization in the others.

General HPV, HPV 16, HPV 18, and HPV 16/18 prevalences are displayed in Table 3. It was observed that higher rates of HPV infection occurred in patients with oral lesions and in people in high-risk groups (patients with genital lesions or infected partners). It was also noted that the healthy population had a very low HPV infection rate (6.2%; 95% CI 5.7–6.7%).

Table 3.

HPV status in each subgroup.

| Article | Total | HPV+ | HPV 16 | HPV 18 | HPV 16/18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in healthy patients | |||||

| Cortezzi (2004)15 | 142 | 15 (10.6%) | 13 (9.1%) | – | 13 (9.1%) |

| Gonçalves (2006)37 | 70 | 3 (4.3%) | – | – | – |

| Sacramento (2006)6 | 50 | 7 (14.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 2 (4.0%) |

| Silva (2007)16 | 10 | 1 (10.0%) | – | – | – |

| Esquenazi (2010)7 | 100 | 0 (0.0%) | – | – | – |

| Horewicz (2010)8 | 104 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | – |

| Araujo (2011)45 | 16 | 1 (6.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Betiol (2012)13 | 16 | 3 (18.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (18.8%) | 3 (18.8%) |

| Fonseca-Silva (2012)14 | 24 | 7 (29.2%) | 5 (20.8%) | 2 (8.3%) | 7 (29.2%) |

| Tristão (2012)9 | 125 | 29 (23.2%) | – | – | – |

| Kreimer (2013)10 | 499 | 10 (2.0%) | 3 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.6%) |

| Cavenaghi (2013)5 | 124 | 3 (2.4%) | – | – | – |

| Araujo (2014)11 | 166 | 40 (24.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (3.0%) | 5 (3.0%) |

| Lima (2014)46 | 100 | 2 (2.0%) | – | – | – |

| Machado (2014)12 | 514 | 7 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Total | 2060 |

128/2060 (6.2%) (95% CI 5.7%–6.7%) |

22/1551 (1.4%) (95% CI 1.2%–1.6%) |

11/1285 (0.9%) (95% CI 0.8%–1.0%) |

33/1551 (2.1%) (95% CI 1.9%–2.3%) |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in patients with benign lesions | |||||

| Soares (2003)19 | 30 | 6 (20.0%) | – | – | 2 (6.7%) |

| Fregonesi (2003) | 19 | 6 (31.6%) | – | – | 4 (21.0%) |

| Lira (2010)22 | 16 | 16 (100.0%) | – | – | – |

| Mazon (2011)17 | 18 | 6 (33.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Fregonezi (2012)23 | 18 | 11 (61.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (39.0%) | 7 (39.0%) |

| Total | 101 |

45/101 (44.6%) (95% CI 43.7–45.4) |

0/36 (0.0%) (95% CI NA) |

7/36 (19.4%) (95% CI 17.8–21.1) |

13/85 (15.3%) (95% CI 14.7–15.9) |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in patients with premalignant lesions | |||||

| Soares (2002)18 | 20 | 2 (10.0%) | – | – | – |

| Fregonesi (2003)20 | 10 | 6 (60.0%) | – | – | 4 (40.0%) |

| Acay (2008) | 40 | 9 (22.5%) | – | – | 5 (12.5%) |

| Mazon (2011)17 | 18 | 4 (22.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (22.0%) | 4 (22.0%) |

| Betiol (2012)13 | 8 | 8 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (62.5%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Fonseca-Silva (2012)14 | 48 | 34 (70.8%) | 31 (64.6%) | 3 (6.2%) | 34 (70.8%) |

| Fregonezi (2012)23 | 16 | 8 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (25.0%) | 4 (25.0%) |

| Total | 160 |

71/160 (44.4%) (95% CI 42.7%–46.1%) |

31/90 (34.4%) (95% CI 31.2%–37.7%) |

16/90 (17.8%) (95% CI 17.6%–38.6%) |

51/140 (36.4%) (95% CI 34.4%–38.6%) |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in patients with oral or oropharyngeal SCC | |||||

| Miguel (1998)24 | 28 | 4 (14.3%) | – | – | – |

| Soares (2002)18 | 10 | 0 (0.0%) | – | – | – |

| Soares (2003)19 | 27 | 13 (48.1%) | – | – | 10 (37.0%) |

| Fregonesi (2003)20 | 17 | 6 (35.3%) | – | – | 5 (29.0%) |

| Cortezzi (2004)15 | 16 | 4 (25.0%) | 4 (25.0%) | – | – |

| Silva (2007)16 | 50 | 37 (74.0%) | – | – | – |

| Soares (2007)25 | 75 | 18 (24.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 14 (18.7%) | 15 (20.0%) |

| Acay (2008)21 | 10 | 3 (30.0%) | – | – | 2 (20.0%) |

| Oliveira (2008)26 | 87 | 17 (19.5%) | 4 (4.6%) | 3 (3.4%) | 7 (8.0%) |

| Simonato (2008)27 | 29 | 5 (17.2%) | – | – | – |

| Soares (2008)28 | 33 | 11 (33.3%) | 2 (6.1%) | 9 (27.3%) | 11 (33.3%) |

| Oliveira (2009)29 | 88 | 26 (29.5%) | 1 (3.8%) | 21 (80.8%) | 22 (25.0%) |

| Lira (2010)22 | 70 | 63 (90.0%) | 11 (13.9%) | 17 (21.5%) | 28 (40.0%) |

| Mazon (2011)17 | 19 | 11 (58.0%) | 1 (5.3%) | 10 (53.0%) | 11 (58.0%) |

| Pereira (2011)30 | 27 | 9 (33.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | 9 (33.3%) | 9 (33.3%) |

| Spindula-Filho (2011)31 | 47 | 0 (0.0%) | – | – | – |

| Cordeiro-Silva (2012)32 | 45 | 3 (6.0%) | – | – | – |

| Fregonezi (2012)23 | 17 | 5 (29.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (11.8%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Kaminagakura (2012)33 | 114 | 22 (19.2%) | 22 (19.2%) | – | 22 (19.2%) |

| Marques-Silva (2012)34 | 40 | 30 (75.0%) | 10 (25.0%) | 23 (57.5%) | 30 (75.0%) |

| Cantarutti (2014)35 | 26 | 0 (0.0%) | – | – | – |

| Lopez (2014)36 | 222 | 14 (6.3%) | 8 (3.6%) | – | 8 (3.6%) |

| Total | 1097 |

301/1097 (27.4%) (95% CI 26.6%–28.3%) |

65/808 (8.0%) (95% CI 7.6%–8.5%) |

108/456 (23.7%) (95% CI 23.0%–24.4%) |

182/846 (21.5%) (95% CI 20.9%–22.1%) |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in patients with genital lesions, HPV infection, or partners of this population. | |||||

| Gonçalves, 200637 | 70 | 26 (37.1%) | – | – | – |

| Castro, 200941 | 30 | 0 (0.0%) | – | – | – |

| Xavier, 200942 | 30 | 1 (3.3%) | – | – | – |

| Peixoto, 201143 | 100 | 81 (81.0%) | – | – | – |

| Zonta, 201244 | 27 | 23 (85.2%) | 2 (7.4%) | 1 (3.7%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| Marques, 201338 | 64 | 2 (3.1%) | – | – | – |

| Ribeiro, 201439 | 62 | 30 (48.4%) | – | – | – |

| Vidotti, 201440 | 105 | 25 (23.8%) | – | – | – |

| Total | 488 |

188/488 (38.5%) (95% CI 36.2%–40.9%) |

2/23 (7.4%) (95% CI NA) |

1/23 (3.7%) (95% CI NA) |

3/23 (11.1%) (95% CI NA) |

| Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection in immunodeficient patients | |||||

| Araujo, 201145 | 60 | 20 (33.3%) | 8 (13.3%) | 2 (3.3%) | 10 (16.7%) |

| Lima, 201446 | 100 | 11 (11.0%) | – | – | – |

| Total | 160 |

31/160 (19.4%) (95% CI 18.4%–20.4%) |

8/60 (13.3%) (95% CI NA) |

2/60 (3.3%) (95% CI NA) |

10/60 (16.7%) (95% CI NA) |

The risk of HPV infection was estimated for each subgroup (Table 4). It was evident that, when compared to the healthy population, the risk of HPV infection was approximately 1.5- to 9.0-fold higher, especially in patients with an immunodeficiency, oral lesions, and SCC. The rates of the most well-known oncogenic types (HPV 16 and/or 18) also show this increased risk.

Table 4.

Risk of HPV infection in each subgroup.

| Group | OR (95% CI) | pa |

|---|---|---|

| Any HPV infection | ||

| Healthy patients | Reference | – |

| Immunodeficient patients | 5.797 (3.696–9.091) | <0.0001 |

| Risk group | 3.888 (3.369–4.487) | <0.0001 |

| Benign lesions | 2.686 (2.312–3.121) | <0.0001 |

| Premalignant lesions | 2.094 (1.904–2.304) | <0.0001 |

| Oral or oropharyngeal SCC | 3.097 (2.700–3.553) | <0.0001 |

| HPV 16 infection | ||

| Healthy patients | Reference | – |

| Immunodeficient patients | 9.400 (4.021–21.977) | <0.0001 |

| Risk group | 2.476 (1.167–5.255) | 0.018 |

| Benign lesions | N/C | – |

| Premalignant lesions | 2.467 (2.121–2.870) | <0.0001 |

| Oral or oropharyngeal SCC | 1.725 (1.180–1.522) | 0.005 |

| HPV 18 infection | ||

| Healthy patients | Reference | – |

| Immunodeficient patients | 3.894 (0.844–17.960) | 0.081 |

| Risk group | 2.254 (0.793–6.402) | 0.127 |

| Benign lesions | 3.044 (2.169–4.271) | <0.0001 |

| Premalignant lesions | 2.242 (1.839–2.740) | <0.0001 |

| Oral or oropharyngeal SCC | 2.051 (1.807–2.327) | <0.0001 |

| HPV 16/18 infection | ||

| Healthy patients | Reference | – |

| Immunodeficient patients | 7.833 (3.689–16.633) | <0.0001 |

| Risk group | 2.476 (1.324–4.629) | 0.005 |

| Benign lesions | 2.040 (1.624–2.562) | <0.0001 |

| Premalignant lesions | 2.278 (2.017–2.573) | <0.0001 |

| Oral or oropharyngeal SCC | 1.477 (1.043–2.092) | 0.028 |

N/C, not calculated because there was no valid case for analysis.

Logistic regression.

Discussion

This studied summarized, for the first time, the prevalence of oral and oropharyngeal infections in the Brazilian population. This systematic review was conducted with a large series of oral and oropharyngeal HPV statuses in different populations, and data were stratified into groups of patients in order to acquire clinically relevant information toward the management of each specific group. However, some points require discussion.

Oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection

The prevalence of oral HPV has been estimated to be in the range 2.4–7.5% among young adults in the United States.47 A recent study48 investigated the prevalence of oral HPV infections in the general US population (5579 men and women aged between 14 and 69 years) in 2009 and 2010. The overall prevalence of oral HPV infections for any HPV type was 6.9% (95% CI 5.7%–8.3%), the prevalence of high-risk HPV types was 3.7% (95% CI 3.0%–4.6%), and that of HPV 16 was 1.0% (95% CI 0.7%–1.3%). The present study identified a rate of 6.2% for any HPV infection and 1.4% for HPV 16 infection among 2060 healthy patients, which is similar to large series around the world.

Considering other groups analyzed in the present study, other studies also identified an increased prevalence of oral HPV infection. A study conducted in Zagreb, Croatia, established a rate of 17.7% for HPV positivity in oral lesions, with a significantly higher presence in benign proliferative mucosal lesions (18.6%). High-risk HPV types were predominantly found in potentially malignant oral disorders (HPV 16 in 4.3%) with a rate for any HPV infection of 15.5%.49 A meta-analysis conducted with dysplasia specimens from the oral cavity and oropharynx identified an overall prevalence of HPV 16/18 of 24.5% (95% CI 16.4%–36.7%).50 Another study identified a prevalence of 6.9% for oral HPV infection in HIV patients.51 Studies of this relationship in other immunodeficient patients are scarce. Oral HPV infections were found in almost 10.2% to 75% of patients with genital HPV lesions or infected partners worldwide.52, 53

Genomic DNA of oncogenic HPV, especially type 16, has been detected in approximately 25% of HNSCC cases worldwide.54 In a large-scale meta-analysis, Kreimer et al. 55 reported an overall HPV prevalence of 25.9% in HNSCC (23.5% for oral cavity SCC and 35.6% for oropharyngeal SCC). In a recent French multi-institutional study, St Guily et al. 56 reported an overall prevalence of 46.5% for oropharyngeal SCC and 10.5% for oral cavity SCC. The present review established a similar rate of 27.4% for HPV infections in patients with SCC of the oral cavity or oropharynx and of 8.0% specifically for HPV 16 infection. For HPV 18 infection, a rate of 23.7% was observed among SCC patients in the present review, possibly the first report in this field with a large sample. Other series,55 however, reported an unexpected extreme rarity of HPV 18 in the oropharynx that was confirmed in other large studies, and the authors discussed how this was a difficult fact to explain.

O’Rorke et al.57 performed a meta-analysis with 42 articles studying the survival rate of HNSCC patients. They concluded that patients with HPV-positive HNSCC had a 54% better overall survival rate compared to HPV-negative patients (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.37–0.57) and that both progression-free survival and disease-free survival were significantly improved in HPV-positive HNSCCs. This was not the aim of the present review, but it demonstrates the current relevance of the study of this topic.

Demographics

Demographically, patients with HPV-related HNSCCs are more likely to be male, white, non-smokers, non-drinkers, younger in age, and have a higher socioeconomic status.57, 58, 59, 60 Changes in sexual behavior, including a higher number of lifetime sex partners, an increase in oral sex practices, same sex-contact, and earlier age of sexual activity have all been implicated in HPV-related HNSCC.57, 61 Many of the studies included in this review did not present findings by potentially important covariates (age, gender, tobacco use, alcohol use, etc.), as was observed in other studies.55, 62 Moreover, only eight studies (38.1%) employed a cancer-free control group, which is difficult and can sometimes cause an overestimation of the odds ratio of HPV risk infection between HNSCC groups. The same trend was observed by Herrero et al.62

The variations in oral HPV prevalence among different studies may be due to differences in study populations, sampling and testing methods, and possibly the time periods studied.47

Sample analysis

In the absence of a standardized detection technique, considerable variations in the prevalence of HPV infections have been recorded in the literature.54 This was not observed in the present review because the great majority of the studies employed GP 5+/6+ or MY09/11 primers in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or HPV type-specific in situ hybridization.

Geographic distribution

The prevalence of HPV was assessed in a study with 1688 healthy men (median age of 31 years) in the U.S., Mexico, and Brazil. The prevalence of all HPV types was 4.0% (95% CI 3.1%–5.0%).10 The most prevalent high-risk HPV type was HPV 16 in all three countries; however, HPV55 was more common in Mexico compared to the U.S. or Brazil. The geographic heterogeneity might be partly explained by regional differences in the distribution of risk factors other than HPV infection in HNSCC patients.55

The study by Gillison et al.48 estimated an HPV infection rate of 6.9% in the general U.S. population in a sample obtained in 2009 and 2010. This rate was slightly higher than that observed in a systematic review that included data from 1997 to 2009 (4.5%; 95% CI 3.9–5.1).63

These results suggest that the prevalence of HPV may vary depending on distinct population characteristics and the time period studied, which might explain the wide range of HPV prevalence among different studies included in this systematic review.

Limitations

There are a few limitations in this study that should be noted. The most important was in the data collection; because this work was a systematic review of published articles, some data could not be obtained, especially regarding demographics. Additionally, as seen in Fig. 2, the whole Brazilian population was not included, because of the lack of studies in some regions. Another important point is that because aggregate patient data were used, it is possible that there was heterogeneity in these studies and inconsistencies in the datasets that were unknown due to the summarization of the data. Moreover, the majority of the studies were small and used nonprobability samples, and it is difficult to differentiate studies that enrolled consecutive patients from studies that used alternative inclusion criteria, such as institutional archives of paraffin-embedded tissues. Nevertheless, these nonprobability samples did not represent the Brazilian population as a whole; however, the present study is the first one to consolidate the data of oral and oropharyngeal HPV infection in Brazil. HPV prevalence appeared to be inversely proportional to the study sample size, and the poor quality of some of the cancer specimens may also have affected the prevalence estimates. All of these points were also mentioned as limitations in other systematic review series.55

Conclusion

In summary, the healthy Brazilian population has a very low oral/oropharyngeal HPV infection rate. Other groups, such as at-risk patients or their partners, immunodeficient patients, people with oral lesions and, especially, patients with oral cavity or oropharyngeal SCC, have high risks of HPV infection. Because aggregate patient data results varied, a large-scale study considering the whole country, including a more diverse population, must be conducted to confirm the findings of this review.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: de Matos LL, Miranda GA, Cernea CR. Prevalence of oral and oropharyngeal human papillomavirus infection in Brazilian population studies: a systematic review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81:554–67.

References

- 1.Sanders A.E., Slade G.D., Patton L.L. National prevalence of oral HPV infection and related risk factors in the U.S. adult population. Oral Dis. 2012;18:430–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matos L.L., Manfro G., Santos R.V., Stabenow E., Mello E.S., Alves V.A., et al. Tumor thickness as a predictive factor of lymph node metastasis and disease recurrence in T1N0 and T2N0 squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinto F.R., de Matos L.L., Palermo F.C., Kulcsar M.A., Cavalheiro B.G., de Mello E.S., et al. Tumor thickness as an independent risk factor of early recurrence in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:1747–1754. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2704-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller C.S., Johnstone B.M. Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis, 1982–1997. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:622–635. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.115392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavenaghi V.B., Ghosn E.J., Cruz N., Rossi L.M., da Silva L., Costa H.O., et al. Determination of HPV prevalence in oral/oropharyngeal mucosa samples in a rural district of Sao Paulo. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;79:599–602. doi: 10.5935/1808-8694.20130107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacramento P.R., Babeto E., Colombo J., Cabral Ruback M.J., Bonilha J.L., Fernandes A.M., et al. The prevalence of human papillomavirus in the oropharynx in healthy individuals in a Brazilian population. J Med Virol. 2006;78:614–618. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esquenazi D., Bussoloti Filho I., Carvalho Mda G., Barros F.S. The frequency of human papillomavirus findings in normal oral mucosa of healthy people by PCR. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76:78–84. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942010000100013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horewicz V.V., Feres M., Rapp G.E., Yasuda V., Cury P.R. Human papillomavirus-16 prevalence in gingival tissue and its association with periodontal destruction: a case–control study. J Periodontol. 2010;81:562–568. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tristao W., Ribeiro R.M., Oliveira C.A., Betiol J.C., Bettini Jde S. Epidemiological study of HPV in oral mucosa through PCR. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;78:66–70. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942012000400013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreimer A.R., Pierce Campbell C.M., Lin H.Y., Fulp W., Papenfuss M.R., Abrahamsen M., et al. Incidence and clearance of oral human papillomavirus infection in men: the HIM cohort study. Lancet. 2013;382:877–887. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60809-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Araujo M.V., Pinheiro H.H., Pinheiro Jde J., Quaresma J.A., Fuzii H.T., Medeiros R.C. Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in Belem, Para State, Brazil, in the oral cavity of individuals without clinically diagnosable injuries. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30:1115–1119. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00138513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machado A.P., Gatto de Almeida F., Bonin C.M., Martins Prata T.T., Sobrinho Avilla L., Junqueira Padovani C.T., et al. Presence of highly oncogenic human papillomavirus in the oral mucosa of asymptomatic men. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18:266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betiol J.C., Kignel S., Tristao W., Arruda A.C., Santos S.K., Barbieri R., et al. HPV 18 prevalence in oral mucosa diagnosed with verrucous leukoplakia: cytological and molecular analysis. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:769–770. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonseca-Silva T., Farias L.C., Cardoso C.M., Souza L.R., Carvalho Fraga C.A., Oliveira M.V., et al. Analysis of p16(CDKN2A) methylation and HPV-16 infection in oral mucosal dysplasia. Pathobiology. 2012;79:94–100. doi: 10.1159/000334926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortezzi S.S., Provazzi P.J., Sobrinho J.S., Mann-Prado J.C., Reis P.M., de Freitas S.E., et al. Analysis of human papillomavirus prevalence and TP53 polymorphism in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;150:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva C.E., da Silva I.D., Cerri A., Weckx L.L. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:497–500. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazon R.C., Rovigatti Gerbelli T., Benatti Neto C., de Oliveira M.R., Antonio Donadi E., Guimaraes Goncalves M.A., et al. Abnormal cell-cycle expression of the proteins p27, mdm2 and cathepsin B in oral squamous-cell carcinoma infected with human papillomavirus. Acta Histochem. 2011;113:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soares C.P., Malavazi I., dos Reis R.I., Neves K.A., Zuanon J.A., Benatti Neto C., et al. Presence of human papillomavirus in malignant oral lesions. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2002;35:439–444. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822002000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soares C.P., Benatti Neto C., Fregonezi P.A., Teresa D.B., Santos R.T., Longatto Filho A., et al. Computer-assisted analysis of p53 and PCNA expression in oral lesions infected with human papillomavirus. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2003;25:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fregonesi P.A., Teresa D.B., Duarte R.A., Neto C.B., de Oliveira M.R. Soares CP. p16(INK4A) immunohistochemical overexpression in premalignant and malignant oral lesions infected with human papillomavirus. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:1291–1297. doi: 10.1177/002215540305101006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acay R., Rezende N., Fontes A., Aburad A., Nunes F., Sousa S. Human papillomavirus as a risk factor in oral carcinogenesis: a study using in situ hybridization with signal amplification. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2008;23:271–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lira R.C., Miranda F.A., Guimaraes M.C., Simoes R.T., Donadi E.A., Soares C.P., et al. BUBR1 expression in benign oral lesions and squamous cell carcinomas: correlation with human papillomavirus. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:1027–1036. doi: 10.3892/or_00000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fregonezi P.A., Silva T.G., Simoes R.T., Moreau P., Carosella E.D., Klay C.P., et al. Expression of nonclassical molecule human leukocyte antigen-G in oral lesions. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012;33:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miguel R.E., Villa L.L., Cordeiro A.C., Prado J.C., Sobrinho J.S., Kowalski L.P. Low prevalence of human papillomavirus in a geographic region with a high incidence of head and neck cancer. Am J Surg. 1998;176:428–429. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soares R.C., Oliveira M.C., Souza L.B., Costa A.L., Medeiros S.R., Pinto L.P. Human papillomavirus in oral squamous cells carcinoma in a population of 75 Brazilian patients. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007;28:397–400. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira L.R., Ribeiro-Silva A., Ramalho L.N., Simoes A.L., Zucoloto S. HPV infection in Brazilian oral squamous cell carcinomapatients and its correlation with clinicopathological outcomes. Mol Med Rep. 2008;1:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simonato L.E., Garcia J.F., Sundefeld M.L., Mattar N.J., Veronese L.A., Miyahara G.I. Detection of HPV in mouth floor squamous cell carcinoma and its correlation with clinicopathologic variables, risk factors and survival. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:593–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soares R.C., Oliveira M.C., de Souza L.B., Costa Ade L., Pinto L.P. Detection of HPV DNA and immunohistochemical expression of cell cycle proteins in oral carcinoma in a population of Brazilian patients. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008;16:340–344. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572008000500007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliveira M.C., Soares R.C., Pinto L.P., Souza L.B., Medeiros S.R., Costa Ade L. High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) is not associated with p53 and bcl-2 expression in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pereira K.M., Soares R.C., Oliveira M.C., Pinto L.P., Costa Ade L. Immunohistochemical staining of Langerhans cells in HPV-positive and HPV-negative cases of oral squamous cells carcinoma. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:378–383. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572011005000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spindula-Filho J.V., da Cruz A.D., Oton-Leite A.F., Batista A.C., Leles C.R., de Cassia Goncalves Alencar R., et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma versus oral verrucous carcinoma: an approach to cellular proliferation and negative relation to human papillomavirus (HPV) Tumour Biol. 2011;32:409–416. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cordeiro-Silva M.F., Stur E., Agostini L.P., de Podesta J.R., de Oliveira J.C., Soares M.S., et al. Promoter hypermethylation in primary squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx: a study of a Brazilian cohort. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:10111–10119. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1885-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaminagakura E., Villa L.L., Andreoli M.A., Sobrinho J.S., Vartanian J.G., Soares F.A., et al. High-risk human papillomavirus in oral squamous cell carcinoma of young patients. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1726–1732. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marques-Silva L., Farias L.C., Fraga C.A., de Oliveira M.V., Cardos C.M., Fonseca-Silva T., et al. HPV-16/18 detection does not affect the prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in younger and older patients. Oncol Lett. 2012;3:945–949. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cantarutti A.L., Fernandes L.P., Saldanha M.V., Marques A.E., Vianna L.M., de Melo N.S., et al. Evaluation of immunohistochemical expression of p16 and presence of human papillomavirus in oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:210–214. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopez R.V., Levi J.E., Eluf-Neto J., Koifman R.J., Koifman S., Curado M.P., et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 and the prognosis of head and neck cancer in a geographical region with a low prevalence of HPV infection. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:461–471. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0348-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goncalves A.K., Giraldo P., Barros-Mazon S., Gondo M.L., Amaral R.L., Jacyntho C. Secretory immunoglobulin A in saliva of women with oral and genital HPV infection. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;124:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marques A.E., Fernandes L.P., Cantarutti A.L., Oyama C.N., Figueiredo P.T., Guerra E.N. Assessing oral brushing technique as a source to collect DNA and its use in detecting human papillomavirus. Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribeiro C.M.B., Ferrer I., Santos de Farias A.B., Fonseca D.D., Morais Silva I.H., Monteiro Gueiros L.A., et al. Oral and genital HPV genotypic concordance between sexual partners. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s00784-013-0959-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vidotti L.R., Vidal F.C., Monteiro S.C., Nunes J.D., Salgado J.V., Brito L.M., et al. Association between oral DNA-HPV and genital DNA-HPV. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014;43:289–292. doi: 10.1111/jop.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castro T.M., Bussoloti Filho I., Nascimento V.X., Xavier S.D. HPV detection in the oral and genital mucosa of women with positive histopathological exam for genital HPV, by means of the PCR. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75:167–171. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30773-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xavier S.D., Bussoloti Filho I., de Carvalho J.M., Castro T.M., Framil V.M., Syrjanen K.J. Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in oral mucosa of men with anogenital HPV infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:732–737. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peixoto A.P., Campos G.S., Queiroz L.B., Sardi S.I. Asymptomatic oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in women with a histopathologic diagnosis of genital HPV. J Oral Sci. 2011;53:451–459. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.53.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zonta M.A., Monteiro J., Santos G., Jr., Pignatari A.C. Oral infection by the human papilloma virus in women with cervical lesions at a prison in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;78:66–72. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942012000200011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Araujo M.R., Rubira-Bullen I.R., Santos C.F., Dionisio T.J., Bonfim C.M., De Marco L., et al. High prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infection in Fanconi's anemia patients. Oral Dis. 2011;17:572–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lima M.D., Braz-Silva P.H., Pereira S.M., Riera C., Coelho A.C., Gallottini M. Oral and cervical HPV infection in HIV-positive and HIV-negative women attending a sexual health clinic in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chung C.H., Bagheri A., D'Souza G. Epidemiology of oral human papillomavirus infection. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gillison M.L., Broutian T., Pickard R.K., Tong Z.Y., Xiao W., Kahle L., et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:693–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mravak-Stipetic M., Sabol I., Kranjcic J., Knezevic M., Grce M. Human papillomavirus in the lesions of the oral mucosa according to topography. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e69736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jayaprakash V., Reid M., Hatton E., Merzianu M., Rigual N., Marshall J., et al. Human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in epithelial dysplasia of oral cavity and oropharynx: a meta-analysis, 1985–2010. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:1048–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anaya-Saavedra G., Flores-Moreno B., Garcia-Carranca A., Irigoyen-Camacho E., Guido-Jimenez M., Ramirez-Amador V. HPV oral lesions in HIV-infected patients: the impact of long-term HAART. J Oral Pathol Med. 2013;42:443–449. doi: 10.1111/jop.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogt S.L., Gravitt P.E., Martinson N.A., Hoffmann J., D'Souza G. Concordant oral-genital HPV infection in South Africa couples: evidence for transmission. Front Oncol. 2013;3:303. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ragin C., Edwards R., Larkins-Pettigrew M., Taioli E., Eckstein S., Thurman N., et al. Oral HPV infection and sexuality: a cross-sectional study in women. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:3928–3940. doi: 10.3390/ijms12063928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melkane A.E., Auperin A., Saulnier P., Lacroix L., Vielh P., Casiraghi O., et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and prognostic implication in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Head Neck. 2014;36:257–265. doi: 10.1002/hed.23302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kreimer A.R., Clifford G.M., Boyle P., Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:467–475. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.St Guily J.L., Jacquard A.C., Pretet J.L., Haesebaert J., Beby-Defaux A., Clavel C., et al. Human papillomavirus genotype distribution in oropharynx and oral cavity cancer in France – the EDiTH VI study. J Clin Virol. 2011;51:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O’Rorke M.A., Ellison M.V., Murray L.J., Moran M., James J., Anderson L.A. Human papillomavirus related head and neck cancer survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:1191–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaturvedi A.K., Engels E.A., Anderson W.F., Gillison M.L. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:612–619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ang K.K., Harris J., Wheeler R., Weber R., Rosenthal D.I., Nguyen-Tan P.F., et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D'Souza G., Kreimer A.R., Viscidi R., Pawlita M., Fakhry C., Koch W.M., et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1944–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heck J.E., Berthiller J., Vaccarella S., Winn D.M., Smith E.M., Shan’gina O., et al. Sexual behaviours and the risk of head and neck cancers: a pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:166–181. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herrero R., Castellsague X., Pawlita M., Lissowska J., Kee F., Balaram P., et al. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1772–1783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kreimer A.R., Bhatia R.K., Messeguer A.L., Gonzalez P., Herrero R., Giuliano A.R. Oral human papillomavirus in healthy individuals: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:386–391. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c94a3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]