Abstract

Background

To date there have been no comprehensive reports of the work performed by 9/11 World Trade Center responders.

Methods

18,969 responders enrolled in the WTC Medical Monitoring and Treatment Program were used to describe workers’ pre-9/11 occupations, WTC work activities and locations from September 11, 2001 to June 2002.

Results

The most common pre-9/11 occupation was protective services (47%); other common occupations included construction, telecommunications, transportation, and support services workers. 14% served as volunteers. Almost one-half began work on 9/11 and >80% reported working on or adjacent to the “pile” at Ground Zero. Initially, the most common activity was search and rescue but subsequently, the activities of most responders related to their pre-9/11 occupations. Other major activities included security; personnel support; buildings and grounds cleaning; and telecommunications repair.

Conclusions

The spatial, temporal, occupational, and task-related taxonomy reported here will aid the development of a job-exposure matrix, assist in assessment of disease risk, and improve planning and training for responders in future urban disasters.

Keywords: World Trade Center, WTC, 9/11, emergency responder, disaster, task, exposure, exposure assessment, emergency planning, occupational health

INTRODUCTION

On September 11, 2001, over 15,000 people were in the World Trade Center towers when the first flight crashed into the North Tower at 8:46 AM [Murphy, 2009]. As the WTC commission reports; “In the 17-minute period between 8:46 and 9:03 AM on September 11, New York City and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (NJ) had mobilized the largest rescue operation in the city’s history. Then the second plane hit.” [National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, 2004] . In all, more than 70 engine, ladder, rescue, and hazmat groups from the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) and more than 2,000 New York City Police Department (NYPD) officers were mobilized to the site by 9:15 AM [National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, 2004]. Within 2 hr the towers had collapsed from structural failures, and the area south of Canal Street was evacuated [CNN, 2001; Bradt, 2003]. The Federal Response Plan was activated, bringing assistance to the area from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, disaster medical assistance teams, and other resources. The New York City Office of Emergency Management had oversight of all emergency operations at Ground Zero including work by the NYPD, National Guard, FDNY, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and 10 municipal, 5 state, 15 federal, and 10 private agencies or companies [Bradt, 2003]. Ultimately, tens of thousands of workers and volunteers responded to the disaster, which was one of the worst urban environmental disasters in United States history.

The disaster response initially focused on locating and evacuating survivors from collapsed and damaged buildings. In subsequent weeks efforts moved to assessing damage, searching for remains, restoring utilities, repairing infrastructure, cleaning adjacent buildings, and removing debris from the site. Thus, the overall response effort had two phases: (1) crisis response and (2) management, recovery, and restoration. There was also a transition period when the two types of work overlapped [Jederberg, 2005].

Prior studies have documented that WTC responders were a very heterogeneous population who worked for different periods in varying locations [Herbert et al., 2006; Wheeler et al., 2007]. In addition to traditional first responders, a diverse group of non-traditional responders also were involved, and these non-traditional responders worked in both the initial crisis response as well as in the subsequent management and clean-up phases, often working alongside traditional first responders.

To date, there has been no detailed characterization of the work of the WTC responder population or of the multiple job tasks that they performed, often under harrowing and heroic conditions. Previous studies have reported that some of the health consequences among responders varied depending on the time of arrival at the site, whether they were entrapped in the dust cloud at the collapse, and their duration of work [Banauch et al., 2006; Herbert et al., 2006; Wheeler et al. 2007; Skloot et al., 2009].

The purpose of this study is to provide a comprehensive description of the WTC responder population including their demographics, pre-9/11 occupations, and the types, locations, and timing of the job tasks that they performed at Ground Zero. This information is essential for developing a comprehensive exposure assessment, building job-exposure matrices, informing interpretation of health findings, and for future urban disaster planning.

METHODS

The study was conducted using data collected from 9/11 responders as part of the structured interviewer-administered medical and exposure questionnaires taken from each of the responders participating in the WTC Medical Monitoring and Treatment Program (MMTP) and was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. This program was established in 2002 to monitor eligible responders for physical and mental health conditions possibly related to WTC work and exposures [Herbert et al., 2006]. The target population for the MMTP consisted of all non-FDNY workers and volunteers who were engaged in rescue, recovery, restoration of services, cleanup, or other support work on or after 9/11 [Savitz et al., 2008]. To be eligible, a responder had to work for ≥4 hr on 9/11 to 9/14, 2001, ≥24 hr during the month of September, 2001 or ≥80 hr total during the period of October through December, 2001. In addition, employees of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) who processed human remains after 9/11, Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation workers who participated in the cleanup efforts for ≥24 hr from February to July, 2002, or workers who drove, repaired, cleaned, or maintained vehicles that handled WTC debris were eligible to participate in the program [Herbert et al., 2006; Savitz et al., 2008]. New York City firefighters and officers, other FDNY civilian personnel such as Emergency Medical Services (EMS) technicians and paramedics have been monitored by a separate, parallel program coordinated by the FDNY and thus, are not included in this report.

Of approximately 31,000 persons who met eligibility criteria for program participation, 20,843 completed their baseline MMTP medical examination between July 16, 2002 and September 11, 2008 and consented to data aggregation (approximately 77% of those eligible underwent medical exam and about 90% of those who had medical exams also consented to participate in data aggregation). The exposure assessment questionnaires for 1,874 of the 20,843 did not contain information regarding WTC-related activities, although when screened for admission to the MMTP these responders answered affirmatively to participating in rescue, recovery, demolition, debris cleanup, or other support services such as security or site monitoring at the WTC, Staten Island Landfill or barge loading piers. Nevertheless, without the exposure assessment activity information, they were excluded from this analysis. Therefore, the final cohort reported here includes 18,969 WTC responders.

Demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, and ethnicity) were collected via a self-administered questionnaire. Exposure-related information, including data about pre-9/11 occupation, timing and location of WTC-related work, work activities, whether work was conducted in enclosed areas, and whether the responder was “directly in the cloud of dust (or blackout) from the collapse of the WTC buildings” was collected via an interviewer-administered survey. Pre-9/11 occupation was coded to the first decimal of the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) 2000, although construction trades workers were subsequently coded to the second decimal of the SOC [Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2000]. Where appropriate, SOC codes were then combined to create groups containing similar job duties (Table I and Supplementary Table I).

TABLE I.

Standard Occupational Classification Coding Based on Trade or Profession Reported by Responders for September 10, 2001

| Standard occupational classifications (SOC) and representative occupational titles | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Protective service occupations (33-0000) | 8,941 | 47.1 |

| NYC local municipality, Port Authority and other law enforcement agencies including correction officers, detectives, police officers, school safety officers, traffic officers, NYPD and other municipal, regional, and federal agencies; fire and EMS workers from regional fire departments and other city agencies, excluding NYFD; body guards, park rangers, security workers, animal control workers | ||

| Construction occupations (47-0000) | 4,274 | 22.5 |

| Foremen/supervisors; construction workers/demolition workers/laborers, carpenters/dock builders, electricians, heavy equipment operators, iron workers/structural iron and steel, masons, painters, plumbers/pipefitters; Asbestos handlers/hazardous materials removal workers, asphalt pavers, building engineers/inspectors, elevator repair workers, highway repair workers, track workers, fence erectors | ||

| Electrical, telecommunications & other Installation & repair (49-0000) | 1,342 | 7.1 |

| Supervisors; Telecommunication field technicians, telephone installers, utility workers (electric), electrical repairer (powerhouse, substation, relay), telecommunications and electrical power equipment repair and install including line installer; cable splicers, heating, air conditioning and refrigeration mechanics and installers, signal and track switch repair, building maintenance and repair, vehicle and heavy equipment mechanics | ||

| Transportation and material movers (53-0000) | 698 | 3.7 |

| Supervisors; Bus drivers, delivery drivers, motor vehicle drivers(taxi drivers, personal drivers), truck drivers, ambulance drivers; Sanitation workers, convey or operators, crane operator, dredge/excavator operator, hoist/winch operator | ||

| Business, engineering & administration (11-000; 13-000; 17-000) | 1,109 | 5.8 |

| Project managers, human resource and financial managers, Union Representatives, emergency management specialists, claims adjusters, examiners and appraisers engineers, surveyors | ||

| Other occupations | 2,605 | 13.7 |

| Health & personal care professions (21-000; 29-000; 39-000) (2.7% of cohort): Mental health counselors, social workers, clergy, physicians, veterinarians, nurses, chiropractors; EMT, occupational health and safety professional, funeral service workers, barbers and cosmetologist, fitness trainers Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance occupations (37-0000) (2.6% of cohort): janitors, housekeeping, building cleaners, groundskeepers Hourly workers from retail, factory or food preparation occupations (35-000, 41-000, and 51-000) (2.2% of cohort): Cooks, waiters, sales persons, real estate agents, food processing workers, manufacturing trades (metal, plastic, printing, textile, apparel wood), power & chemical plant workers Arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media occupations (27-0000) (1.1% of cohort): Radio and TV announcers, reporters and broadcast staff, photographers, actors, dancers, musicians, designers Miscellaneous occupations (15-000; 19-000; 25-000) (1.6% of cohort): Computer analyst, programmer & support, environmental health scientists, psychologists, sociologists, urban planners, teachers, farming, fishing and forestry workers, health care support workers, legal occupations, military occupations Unemployed & retired (2.0% of cohort) Unknown(1.7% of cohort) | ||

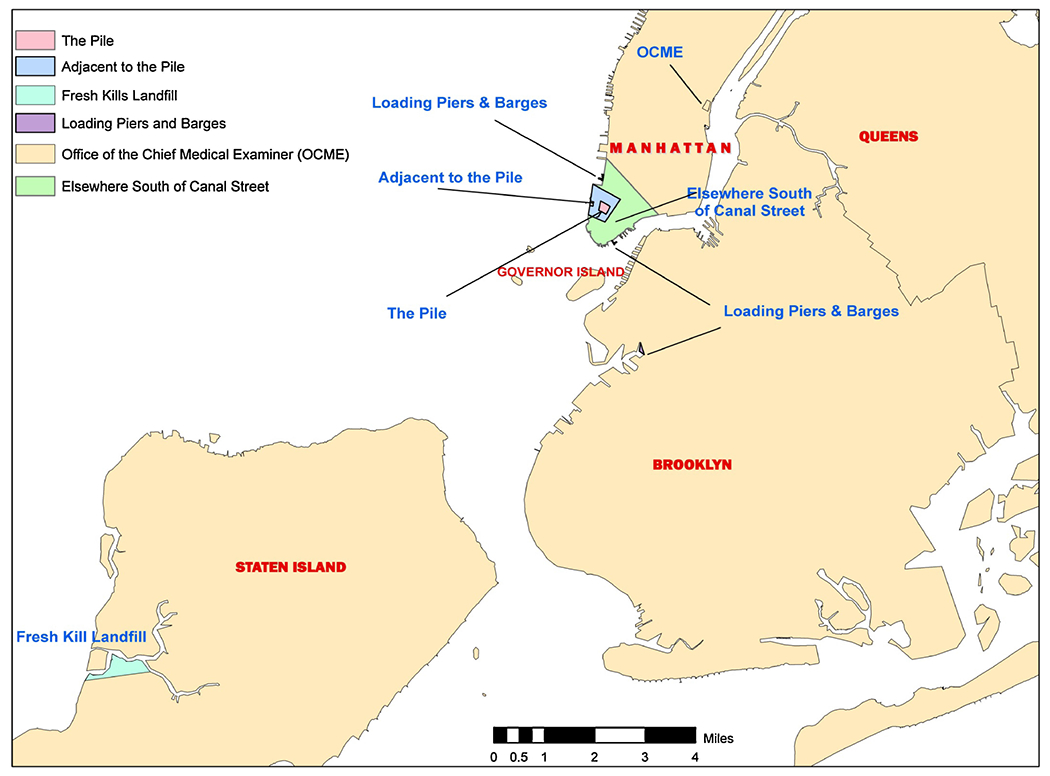

Information about the duration, shift, location of work (using four broad categories); specific activities performed; and whether the responder was a volunteer or paid worker were obtained by trained interviewers from each individual responder for four time periods: September 2001, October 2001, November to December of 2001, and January to June of 2002 [Herbert et al., 2006; Moline et al., 2008]. Responders reported the most common location for their work shift during each of these time periods. Possible location choices were: (1) the “pile” or “pit,” terms that referred to the former location of the twin towers of the WTC complex; (2) “adjacent to the pile” which included locations within approximately four blocks of the pile (this was the secured area immediately surrounding the “pile” and was the site for many support, recovery and restoration activities, the location of several field command centers including those of the NYC Office of Emergency Management (OEM), the Port Authority of NY/NJ, the NYC Department of Design & Construction (DDC), the NYPD and FDNY); (3) the Fresh Kills Landfill on Staten Island where WTC debris was brought for investigation/screening for human remains or personal items, stockpiling, and/or disposal [Bellew, 2004]; (4) “barges/piers,” where material was transferred to barges to go to the Landfill (transfer stations at 59th in Manhattan and Hamilton Avenue in Brooklyn and, later Piers 6 and 25 in lower Manhattan); (5) the OCME at 520 First Avenue in Manhattan, where human remains were processed; and (6) elsewhere south of Canal Street which included a large command center at Police Plaza (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

World Trade Center response and cleanup workforce locations.

To assess responders various activities, a list of 55 job codes was established. For each time-period, information on responders’ activity was collected using up to three of these pre-selected codes. However, many (37 out of 55) of these codes described occupational titles (e.g., police officer, mason, custodian) rather than activities. A more detailed description of activities was also collected by asking responders to describe their main activity at the WTC site for each time period. Two certified industrial hygienists (CIHs) reviewed the text and used the words to create a dictionary of activities. A computer algorithm was developed to identify text strings associated with specific activities using the coding dictionary. Based on this search, each subject was assigned up to 11 different activities for each time period. The resulting activity codes were then validated via a CIH review of a 5% random sample of the corresponding text field data. Overall, 95% of codes matched. Combining the original codes and those generated via the text fields resulted in a list of 97 activities. Because some activities overlapped (e.g., “bucket brigade” and “search and recovery,” or “traffic control” and “perimeter security”), and given that many activities included a small number of responders, the final categories of activities were collapsed into 15 activity groups (Table II).

TABLE II.

Final Activity Groups and Corresponding Description

| Activity group | Description |

|---|---|

| Asbestos removal | Insulation work or any work activity associated with “asbestos” |

| Building and grounds cleaning | Cleaning of buildings, vehicles, ducork, furniture, sidewalks, handling spoiled food, garbage, and furniture |

| Debris removal | Loading and unloading trucks, boats, barges; loading or unloading debris or steel; transporting concrete or cement; hauling debris or material |

| Excavation | Excavation |

| Heavy equipment/demolition and concrete work | Demolition; heavy equipment or construction equipment or machine operator; oiler; cutting and drilling of concrete or granite; pouring of cement or concrete |

| Inspection/supervision | Assessing damage; surveying or monitoring; building inspection; supervisor or foreman |

| Miscellaneous construction | Erecting or dismantling or boarding up entrances, openings, barricades; dust suppression with water; dredging and dewatering; carpentry including dock construction; elevator and escalator installation and repair; installation and repair of windows; painting; roof installation and repair; bridge and road construction and repair; track maintenance and repair |

| Miscellaneous utility work | Sheet metal and ventilation repair; water service, gas, steam, sewer installation, restoration, maintenance and repair; installation, restoration and shutting down of lights and generators; electric work |

| Morgue work | Morgue work; identifying bodies or remains; DNA testing |

| Personnel support services | Religious support services; counseling and psychotherapy; physical therapy, chiropractics, and massage; medical treatment; emergency medical technicians (EMT); respirator fit testing and training and other health and safety training; air and environmental monitoring; health and safety inspections; administration and planning; clerical work (answering phones, paperwork, filing, etc.); interpreting; interviewing; preparing, delivering, and distributing food and water (canteen services); animal care; bringing/transporting/organizing/distributing supplies and materials, other than food and water or site debris; legal activities |

| Search, rescue and recovery | Body bagging and body removal; bucket brigade; handling the search dogs; digging; rescue, search, and recovery; sifting and sorting of debris including on the conveyor belt |

| Security | Escorting people or remains; dispatching and routing vehicles and equipment; traffic control; security; evacuating people; perimeter security |

| Steelwork | Erecting steel; rigging; cutting and welding of metal; fire watch |

| Telephone, cable, computer repair | Installation, repair, maintenance and removal of telephone service; cable installation/repair/splicing; installation, operation, restoration, and shutting down computers |

| Transportation | Operate vehicles/boats/barges/planes/helicopters; towing moving and removing vehicles; truck driving; transporting people; vehicle driver, including ambulances vehicle and equipment maintenance and repair; fueling of vehicles and machines |

RESULTS

The median age of the 18,969 WTC responders was 39 ± 9 years, and 86% were male. In terms of race, 60% were White, 11% Black, and 29% from other races. Approximately 24% reported Hispanic ethnicity.

Occupations

Almost one-half (47%) of the WTC responders in this cohort were employed in the protective services (SOC 33) before 9/11 (Tables I and III). Within the protective services category, the majority (92%) of these workers were law enforcement officers with the largest groups being union members of the NYC Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA), the NYC Detectives’ Endowment Association (DEA), and the NYC Sergeants Benevolent Association (SBA). There were 280 firefighters from fire departments other than FDNY, which has its own WTC monitoring program. In addition, there were retired firefighters who may be included under the category of “Other occupations.” The remaining one-half of the WTC responders were from pre-9/11 occupations not typically identified as emergency responders (Table I). Among these, construction workers (SOC 47) were the most common group (23% of responders). Within this SOC the predominant subgroup was construction trades workers (SOC 47-2000, 13% of all responders). Also within SOC 47 there was a subgroup that was disproportionately Hispanic (47% vs. 18% for trades workers) comprised of “other construction and related workers” (SOC 47-4000, 9% of all WTC responders). This subgroup contained the asbestos/hazardous materials removal workers, as well as fence erectors, elevator repairers, building inspectors and other jobs (Supplementary Table I).

TABLE III.

Demographic Characteristics of Responders According to Pre-9/11 Occupation

| Protective services (SOC33) |

Construction (SOC47) |

Electrical, telecommunications & other installation & repair (SOC 49) |

Transportation & material movers (SOC 53) |

Business, engineering and administrative (SOC 11, 13, 17) |

Other occupations |

Total |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Total number of responders | 8,941 | 47.1 | 4,274 | 22.5 | 1,342 | 7.1 | 698 | 3.7 | 1,109 | 5.9 | 2,605 | 13.7 | 18,969 | 100 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||

| <30 | 1,196 | 13.4 | 533 | 12.5 | 195 | 14.5 | 53 | 7.6 | 96 | 8.7 | 412 | 15.8 | 2,485 | 13.1 |

| 30-39 | 5,049 | 56.5 | 1,494 | 35 | 461 | 34.4 | 223 | 32 | 347 | 31.3 | 798 | 30.6 | 8,372 | 44.1 |

| 40-49 | 2,321 | 25.96 | 1,491 | 34.9 | 431 | 32.1 | 282 | 38.5 | 427 | 38.5 | 809 | 31.1 | 5,761 | 30.4 |

| 50-59 | 348 | 3.9 | 652 | 15.3 | 230 | 17.1 | 126 | 18.2 | 202 | 18.2 | 449 | 17.2 | 2,007 | 10.6 |

| >60 | 27 | 0.3 | 104 | 2.4 | 25 | 1.9 | 14 | 3.3 | 37 | 3.3 | 137 | 5.3 | 344 | 1.8 |

| Male gender | 7,625 | 85.3 | 4,033 | 94.4 | 1,261 | 94 | 669 | 95.9 | 909 | 82 | 1,729 | 66.4 | 16,226 | 85.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| White | 5,624 | 62.9 | 2,411 | 56.4 | 832 | 62 | 375 | 53.7 | 790 | 71.2 | 1,327 | 50.9 | 11,359 | 59.9 |

| Black | 1,033 | 11.6 | 374 | 8.8 | 200 | 14.9 | 112 | 16.1 | 91 | 8.2 | 225 | 8.6 | 2,035 | 10.7 |

| Other | 2,284 | 25.6 | 1,489 | 34.8 | 310 | 23.1 | 211 | 30.2 | 228 | 20.6 | 1,053 | 40.4 | 5,575 | 23.4 |

| Hispanic | 1,878 | 21.0 | 1,227 | 28.7 | 209 | 15.6 | 139 | 20.0 | 167 | 15.1 | 941 | 36.1 | 4,561 | 24.0 |

| Time first began WTC-related work | ||||||||||||||

| 11 Sep. 2001 | ||||||||||||||

| In the dust cloud | 2,595 | 29 | 378 | 8.8 | 163 | 12.2 | 78 | 11.2 | 210 | 18.9 | 410 | 15.7 | 3,834 | 20.2 |

| Not in the dust cloud | 2,797 | 31.3 | 589 | 13.8 | 234 | 17.4 | 126 | 18.1 | 237 | 21.4 | 419 | 16.1 | 4,402 | 23.2 |

| Do not know | 49 | 0.6 | 12 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.8 | 15 | 0.6 | 90 | 0.5 |

| 12–14 Sep. 2001 | 2,640 | 29.5 | 1,826 | 42.7 | 570 | 42.5 | 329 | 47.1 | 412 | 37.2 | 802 | 30.8 | 6,579 | 34.7 |

| 15–30 Sep. 2001 | 622 | 7 | 941 | 22 | 269 | 20 | 112 | 16.1 | 166 | 15 | 663 | 25.5 | 2,773 | 14.6 |

| On or after 10ct. | 140 | 1.6 | 479 | 11.2 | 71 | 5.3 | 34 | 4.9 | 65 | 5.9 | 258 | 9.9 | 1,047 | 5.5 |

| Number of responders during the time period | ||||||||||||||

| September, 2001 | 8,698 | 49.3 | 3,731 | 21.1 | 1,253 | 7.1 | 650 | 3.7 | 1,020 | 5.8 | 2,299 | 13 | 17,651 | 100 |

| October, 2001 | 7,209 | 52.1 | 2,761 | 20 | 1,041 | 7.5 | 478 | 3.5 | 696 | 5 | 1,662 | 12 | 13,847 | 100 |

| November–December, 2001 | 6,196 | 51 | 2,539 | 21 | 929 | 7.6 | 424 | 3.5 | 601 | 4.9 | 1,470 | 12.1 | 12,159 | 100 |

| January–June, 2002 | 4,305 | 51.1 | 1,771 | 21 | 616 | 7.3 | 315 | 3.7 | 445 | 5.3 | 978 | 11.6 | 8,430 | 100 |

| Average days worked (mean, SD) | ||||||||||||||

| September, 2001 | 13.2 | 6.4 | 11.8 | 6.2 | 14.2 | 5.3 | 13 | 6.3 | 11.7 | 6.4 | 10.3 | 6.1 | 12.5 | 6.3 |

| October, 2001 | 17.1 | 9.5 | 22.8 | 8.8 | 23.7 | 8.2 | 22.4 | 9.3 | 19.9 | 9.5 | 19.8 | 9.4 | 19.4 | 9.6 |

| November–December, 2001 | 27 | 17.8 | 38.3 | 18.1 | 38.5 | 16.9 | 38.4 | 18.5 | 33.6 | 18.4 | 34.3 | 18 | 31.9 | 18.6 |

| January–June, 2002 | 49.6 | 46.1 | 77.7 | 52.6 | 84.5 | 52.7 | 84.6 | 55.1 | 82.5 | 54.1 | 70.7 | 50.5 | 63.5 | 51.4 |

| All periods | 72.2 | 66.2 | 86.6 | 77.8 | 101.5 | 78.8 | 95.3 | 85.8 | 81.7 | 83.3 | 72.5 | 73.9 | 79.0 | 73.3 |

The next most common SOC codes comprised in total less than 20% of the responders (Table I and Supplementary Table I). They were SOC 49 (7% of responders), which included a diverse group of installation, maintenance, and repair occupations. Although the majority of these workers were involved in telecommunications or electrical repair work, 10% of the workers in this SOC were listed as vehicle mechanics (SOC 49-3000). We have titled this group (SOC 49) electrical, telecommunications & other installation & repair. In the transportation and material moving group, SOC 53 (4% of total cohort), one-half of the workers (51%) were truck, ambulance or bus drivers, and 35% material moving workers, which includes sanitation and other material moving workers. The business, engineering and administrative group (6% of total cohort) included the SOC categories 11 (management occupations), 13 (business and financial,) and 17 (architecture and engineering). The “other occupations” group (combined <3% of the workforce) included a variety of SOCs. Those with over 45 people included the health professions (SOC 21, 29, and 39), building and grounds maintenance workers (SOC 37), hourly workers from retail, factory or food preparation occupations (SOC 35, 41, and 51), broadcast/media personnel and artists (SOC 27), and miscellaneous occupations such as teacher/librarian (SOC 25), computer programmers/analysts (SOC 15), psychologist, sociologist, and environmental health scientists (SOC 19) as well as retired/unemployed and other unclassified individuals. Within “other occupations” some of the subgroups had high percentages of Hispanic workers including the building and grounds maintenance workers (75%), the retired and unemployed responders (45%) and the hourly workers from retail, factory or food preparation occupations (37%).

Volunteers, not including those who were both employed on site and volunteered, comprised approximately 14% of the WTC responders. The most common pre-9/11 occupations for volunteers included construction (27%) followed by law enforcement (21%), business, engineering and administration (12%), retired and unemployed workers (7%), and health care workers (8%). It should be noted that many responders both worked for pay and also volunteered at the WTC, especially during September when search, rescue and recovery work was ongoing.

Public sector workers made up 61% of the total workforce. These responders can be further subdivided with the majority (45.5% of the total workforce) in the “protective services” group employed in the public sector, mostly the NYPD. The remaining public sector responders (15.5% of the total workforce) were comprised of workers from many NYC agencies, some construction trades’ civil service divisions, and other government workers.

Overall, the number of workers at the WTC decreased with time (Table III). However, the percentage of the overall workforce comprised of each occupational group remained relatively stable over time.

Timeline of Recovery Activities

The total number of responders in our program went from a peak of 17,651 in September, 2001 to 8,430 in the period ending in June, 2002 (Table III). Approximately one-half (44%) of WTC responders began their response work on 9/11. Of these, 46% reported being “directly in the dust cloud (blackout) created from the WTC collapse.” Another 35% of the cohort arrived at the site between 9/12 and 9/14, 2001. Overall, 93% of responders began to work at the site sometime during the month of September, 2001 (Table III).

The majority of responders arriving on 9/11 were in the protective services (65% n = 5,441), followed by workers in construction occupations (12% n = 979), “other occupations” (23%; including business, engineering and administrative professionals (n = 456), electrical, telecommunications & other installation & repair workers (n = 400), and transportation & material movers (n = 206)). Among the protective service workers who arrived on September 11th, 29% were present “directly in the dust cloud (blackout) created from the WTC collapse.” Among business, engineering and administrative professionals 19% were present at the collapse, while for all other occupational groups 9–16% were present at the collapse. Protective service continued to be the most common occupation among responders arriving during 9/12 and 9/14, 2001. From September 15–30, 2001 new responders continued to arrive but at a slower rate.

All occupational groups reported a wide range of days worked (median 56, mean 79, range 1–293 days). One-half (51%) of responders worked <60 days, while only 23% worked >130 days. Responders in the “other occupations” subgroup of buildings and grounds cleaning and maintenance (SOC 37) as well as the electrical, telecommunications & other installation & repair group (SOC 49) had the largest average time on the site (108 and 102 days, respectively), as the utilities infrastructure recovery and repair continued well after the work on the “pile” ended. Conversely, those in protective services and the overall “other occupations” group had the lowest average number of days (72 days) working at the site (Table III).

Many responders worked night shifts as well as day shifts. Data on work shift were available only for the October 2001–June 2002 period. Forty eight percent of responders who worked at any time between October 2001–June 2002 reported working both day and night shifts, with about one-half of protective services workers (56%) reporting work during both shifts (not necessarily back to back). From October through June, 3–5% of the responders reported always or mainly sleeping onsite. The average hours per day worked varied somewhat by time period: September mean 12.3 hr/day (SD 3.3); October mean 11.5 hr/day (SD 2.8); November-December mean 11.1 hr/day (SD 2.6); January–June mean 10.5 hr/day (SD 2.6).

Location of Responders

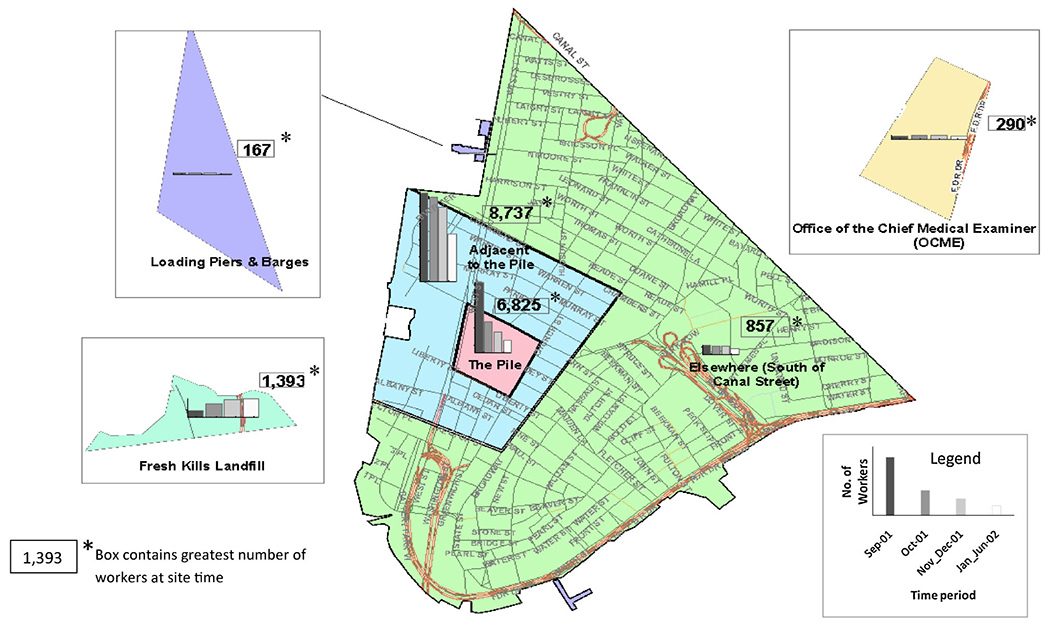

The most common work location was “adjacent to the pile” followed by “on the pile or pit” (Fig. 2). These two locations comprised the secured zone referred to as “Ground Zero.” In September, protective service workers represented the largest group of responders in both of these locations (41% “adjacent to the pile” and 57% on the “pile”). Construction workers comprised the next largest group (24% “adjacent to the pile” and 21% on the “pile”). Over time, the number of responders working on the “pile” decreased as work was completed (from 39% in September to <9% in the January–June 2002 period). Likewise, over the same time frame, the number of responders working in the area “adjacent to the pile” decreased from 51% to 35%. In September 62% (n = 1,352) of all of the volunteers at the WTC reported working on the “pile”, decreasing to <23% (n = 60) in the January–June period. On the other hand, the percent working at the landfill increased over time. Thirty percent of the volunteers worked “adjacent to the pile” in September, but this increased in the subsequent time periods to >50% of all the volunteers.

FIGURE 2.

Number of workers at each location from September 2001 until June 2002.

At the landfill, loading piers/barges, and elsewhere south of Canal Street, protective services workers were again the largest fraction of the workforce (47–80%) in September. Other groups that had an important presence elsewhere south of Canal Street in the four time periods were construction workers (11–13% of workforce), electrical, telecommunications & other installation & repair (11–13% of workforce) and the “other occupations” group (12–14% of workforce). Between 3% and 9% of the volunteers were present elsewhere south of Canal Street between September 2001 and June 2002.

For each of the four time periods, responders were asked if they performed work in an enclosed area, described as “any subgrade level like a tunnel, basement or building or any area not open to the general atmosphere.” In September, 54% of responders reported working in an enclosed area when they also reported spending the majority of their work shift “adjacent to the pile,” 42% reported working in an enclosed area when they also reported their location as “elsewhere south of Canal Street,” 41% when on “the pile,” 33% when at the OCME, 25% when at the barges/piers, and 16% when at the landfill. Overall, the percentage of responders reporting working in an enclosed area decreased slightly during the months after September. Electrical, telecommunications, and other installation and repair workers were the group more likely to report working in an enclosed area (72% of workers), followed by construction workers (59%) and business, engineering, and administration (53%).

Types of Activities by Pre-9/11 Occupation

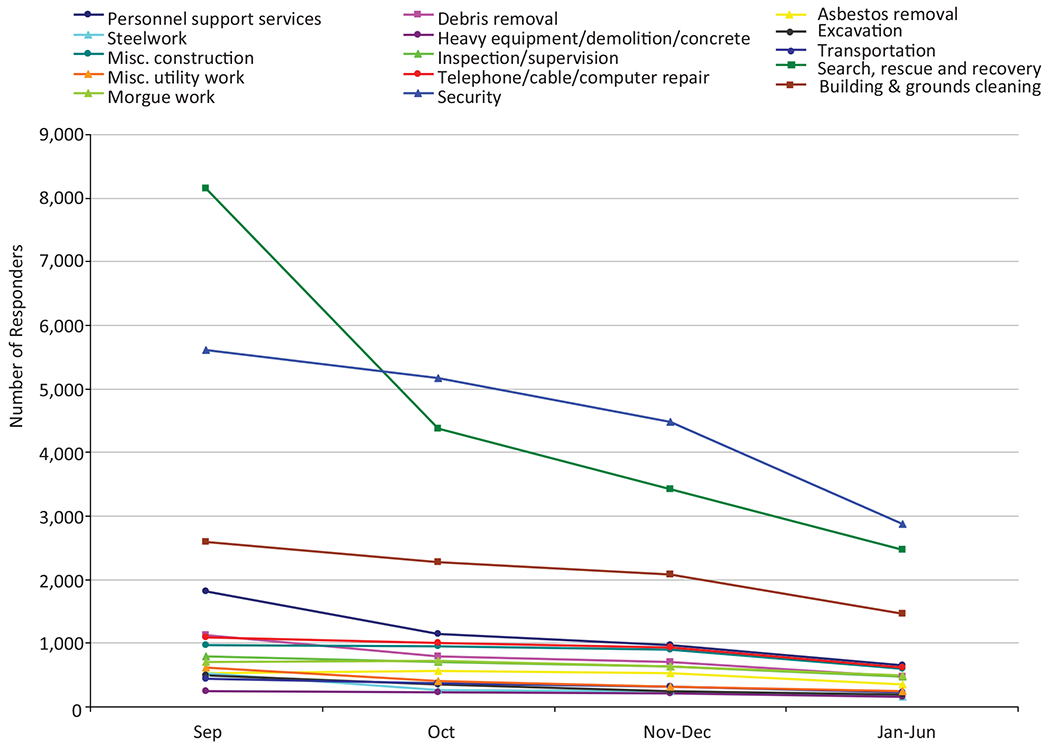

Activities reported by WTC responders over the different time periods are shown in Figure 3. In September, the most frequently reported activity across all occupational groups was search, rescue and recovery (32% of all reported activities). The next most commonly reported activities in September were security (22%), building and grounds cleaning (10%), personnel support (7%), and telephone, cable, and computer repair (4%).

FIGURE 3.

Number of responders by activity and time period.

During the month of October, security related activities became the most commonly reported task (27%), followed by search, rescue and recovery (23%), and building and grounds cleaning (12%). In most categories the percentage of responders involved in the activity remained relatively stable over time. However, search, rescue, and recovery declined after September to about 20%, while security work stayed at about 25% of responders after September.

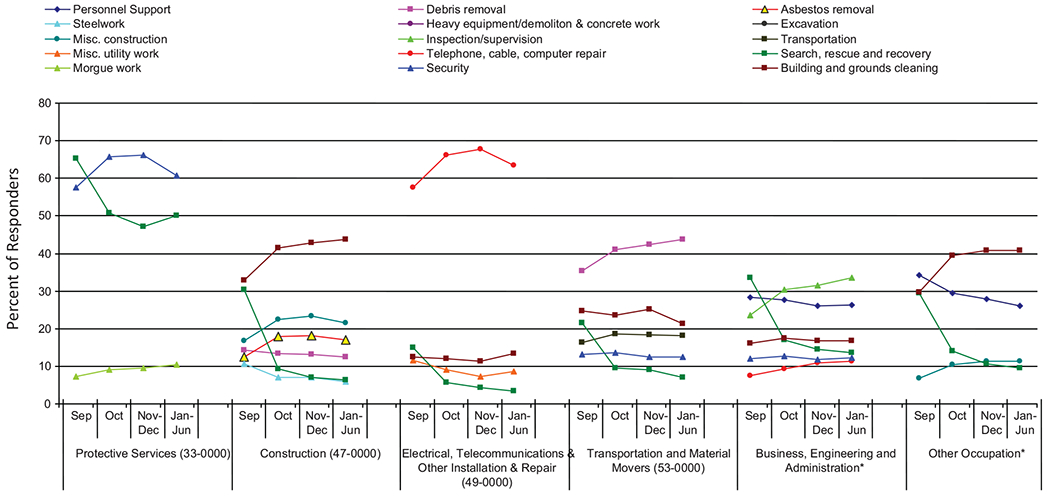

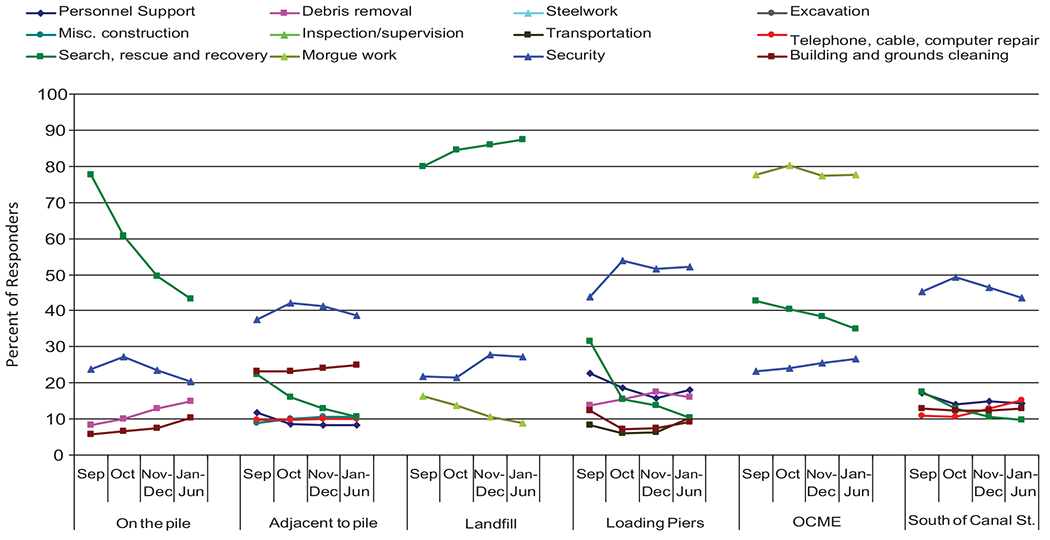

The percent of responders in the SOC groups that reported performing each activity during the four time periods is shown in Figure 4. Overall, all occupational groups reported search, rescue and recovery activities. Moreover, this was the most commonly reported activity in September for protective services, business, engineering, and administrative workers (6,010 responders). After September, most responders engaged in activities related to their pre-9/11 occupations. Yet, all groups (except protective services workers) had a substantial percentage of workers that reported being engaged in building and grounds cleaning. In addition, security activities were reported not only by protective services workers, but also by transportation and retired and unemployed workers (“other occupations” group). Asbestos removal was mostly limited to construction workers, as this SOC group includes the hazardous materials removal workers. Debris removal was reported by construction and transportation workers and business, engineering and administrative workers. Miscellaneous construction activities were conducted by construction and transportation workers and by the “other occupations” group. Telephone, cable, and computer repair was performed by the electrical, telecommunications & other installation & repair SOC group as well as by the business, engineering and administrative SOC group. Miscellaneous utility work was reported by construction SOC group as well as the electrical, telecommunications & other installation & repair SOC group. Among those who reported volunteering in September, 64% report search, rescue, and recovery activities and 30% reported personnel support activities. These two activities were also most commonly reported by volunteers in other time periods. However, in September other activities reported by volunteers included steelwork, building and grounds cleaning and debris removal over (170 persons reported each).

FIGURE 4.

Responders’ activity by pre-9/11 occupation and time period.

The subcategories of the SOC groups were also examined to see if activity patterns varied within a SOC category. Among the protective services SOC (33-000), firefighters (SOC 33-2000) primarily did search, rescue, and recovery activities in all time periods (88–53% reported over time) (Supplementary Fig. 1). These responders in addition to searching the debris for remains, acted as spotters and water sprayers for the operating engineers moving debris and worked in the debris raking field [Meyerwitz, 2006]. The activity pattern of the subgroup of law enforcement responders (33-3000) reflected the overall SOC pattern since this was the predominant subgroup in the SOC. Other protective services (33-9000) which included security guards and animal control workers primarily did security, although 45% also reported search rescue and recovery and 25% reported personnel support activities in September.

For the subgroups in the Construction Trades SOC (47-0000), supervisors (47-1000) and trades workers (47-2000) reported search, rescue, and recovery as their most common activity in September (36% and 42%, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Other common activities reported by 20% or more of supervisors included building and grounds cleaning, inspection/supervision, and miscellaneous construction. The “other construction” related workers (47-4000), which included hazardous material (asbestos) removal workers, reported building and grounds cleaning as their most common activity during all time periods (58-65%). Asbestos removal and miscellaneous construction were reported by over 30% of these responders during all time periods.

Within the construction trades (47-2000), search, rescue, and recovery was the most common activity reported in September for the brick masons (47-2020), carpenters (47-2-30), equipment operators (47-2070), plumbers/pipefitters (47-2150), and ironworkers (47-2220) (Supplementary Fig. 3). For the electricians (47-2110), miscellaneous utility work was the most common in September (51%), while cleaning buildings and grounds was the most common for the painters (47-2140) (54%) and laborers (47-2060) (33%). These trades also did search, rescue and recovery in September (23–30% reporting). Other activities reported by over 20% of responders were: telephone, cable and computer repair by the electricians; debris removal by brick masons and equipment operators; steelwork by the plumbers/pipefitters, iron workers and brick masons; miscellaneous construction work by the carpenters and painters; building and grounds cleaning by brick masons, carpenters, plumbers/pipefitter; heavy equipment/demolition/concrete work and excavation by equipment operators.

Among the overall SOC category of electrical, telecommunications & other installation & repair workers (49-0000), telephone, cable, and computer repair activities were commonly reported for all groups except vehicle mechanics (49-3000) who reported transportation activities most commonly (Supplementary Fig. 4). All subgroups reported search rescue and recovery activities in September (9–29%). However, vehicle mechanics and supervisors (49-1000) had over 20% of workers reporting these activities in September. Other activities reported by over 20% of the responders were buildings and grounds cleaning by the vehicle mechanics and inspection/supervision by the supervisors.

Among the overall SOC category of transportation workers (53-0000) the most common activity was debris removal for supervisors (53-1000) and motor vehicle operators (53–3000) (Supplementary Fig. 4). For the material moving workers (53-7000) cleaning building and grounds was the most common activity followed by debris removal. Note that for all subgroups search, rescue and recovery activities were reported by over 12% of the responders in September.

For the business, engineering and administrative SOCs (11-0000, 13-0000, 17-0000) the most common activities were inspection & supervision by management occupations (11–9000) and engineers (17-2000) and personnel support by the business operations specialists (13-1000) (Supplementary Fig. 5). All SOC subgroups engaged in search rescue and recovery in September (over 30% reported). In all SOC subgroups building and grounds cleaning and debris removal activities were reported by at least 10% of responders during one of the time periods.

For the “other occupations” SOCs (29-0000, 39-0000, 21-0000, 37-0000, 35-0000, 41-0000, 51-0000; 27-000; 25-000, 15-000, 19-000 and retired/unemployed), the activities varied widely. For retail occupations (SOC 41), production occupations (SOC 51) and the unemployed, the most common activity in September was search rescue and recovery. For the health care SOCs (29, 21) media occupations (SOC 27), education occupations (SOC 25), computer occupations (SOC 15), and science occupations (SOC 19) the most common activity was personnel support in all time periods. For building and grounds maintenance workers (SOC 37) and personal care occupations (SOC 39) the most common activity in all time periods was building and grounds cleaning. Food preparation occupations (SOC 35) reported commonly doing both building and grounds cleaning and personnel support.

Types of Activities by Location

Responder activities in relation to the location sites in which they spent most of their work shift are shown in Figure 5. On the “pile,” the most common activity throughout all time periods was search, rescue and recovery (43–78%), followed by security (20–27%) and debris removal (8–15%). Debris removal increased steadily over time, while the fraction of responders reporting search, rescue, and recovery decreased and security remained fairly constant. One of the main search and rescue activities reported in the text fields was working on the bucket brigade. This activity involved extracting metal and concrete debris by hand, filling a bucket and passing it back through a line of responders stationed on the terrain. Another search, rescue and recovery activity on the pile was the raking field where debris was checked for remains [Meyerwitz, 2006].

FIGURE 5.

Responders’ activity by location and time period.

In the location “adjacent to the pile,” security was the most commonly reported activity, in part because of the large proportion of law enforcement responders and the need for security at the more than 30 entry points for the WTC site. In addition to being a crime scene, there were valuable documents and commodities still present at the WTC site and adjacent buildings (including seven Secret Service vaults with government documents and a bank vault with 14,000 pounds of gold in the basement of the collapsed WTC building 7 [Smith, 2002; Reissman and Howard, 2008]). Analyses of the text fields showed that a commonly reported security task was “escorting” of individuals or human remains. Building and ground cleaning was also a common activity in the area “adjacent to the pile” during all time periods given the extensive dust contamination in buildings and enclosed spaces [Lioy and Gochfeld, 2002]. Personnel support activities in this location included provision of food, water, health and safety training, supplies, and equipment. At the service tables and tents that sprang up adjacent to the pile, volunteers handed out “everything from toothbrushes to hydraulic jacks” [Smith, 2002]. The most commonly reported activities in the text fields were the preparation, delivery or distribution of food and water, with many volunteers working long hours at the food services including the “Green Tarp Café” and the “Taj Mahal” [Smith, 2002; Meyerwitz, 2006]. Other personnel support activities included mental health or other types of counseling and provision of medical care. The increasing telephone, cable, and computer repair activities over time in the area “adjacent to the pile” were related to the restoration of the telecommunications hubs and associated infrastructure that provided service to lower Manhattan, including the New York Stock Exchange, City Hall, Federal Plaza, 1 Police Plaza and many other commercial and residential sites. One such hub was the Verizon building on the north side of the Ground Zero site which was heavily damaged by debris from the collapse of the towers, the collapse of WTC 7 against its east side, a diesel spill and flooding of the sub-basements destroying critical components of the voice and data network.

At the landfill, responders primarily reported search, rescue, and recovery activities (80–87%), followed by security (22–28%) and morgue related work (9–16%). The main activity described in the text fields was to manually, or with the use of conveyor belts, sift through debris looking for human remains, personal effects or crime scene evidence. At the OCME, morgue-related work was the most commonly reported task as expected (77–80%), followed by search, rescue, and recovery (35–42%), and security (23–27%).

At the loading piers and barges, responders mainly reported security-related activities (44–54%) although in September, search, rescue and recovery and personnel support services were also quite common (32% and 23%, respectively). After September, the focus shifted to debris removal as the operations moved from the rescue phase to the recovery phase.

Finally, in the area elsewhere south of Canal Street, security was the main activity (44–49%) due to the disaster location in the heart of Wall Street as well as the presence of many other commercial and residential properties. Personnel support (~15%) was fairly constant across the different time periods, while telecommunications, cable, and computer repair activities increased with time (11–15% of responders). Building and ground cleaning was reported by about 12% of responders across all time periods because of the millions of square feet of residential and commercial building space contaminated by the dust cloud produced from the collapse and the fires that burned for several months afterwards. In this area, there was a great effort put into cleaning and reopening the major financial centers in an attempt to lessen the economic impact of the WTC collapse.

Female WTC Responders

Women responders were 15% (n = 2,743) of the WTC cohort. About 39% were white and 18% were black. Compared to men, more women were Hispanic (41% vs. 21%). Like men, about one-half (48%) were protective service workers, but fewer women worked in construction occupations (9% vs. 25%) and in transportation occupations (1% vs. 4%). Women arrived at the sites slightly later than men. Seventeen percent (vs. 21%) arrived on 9/11 in the dust cloud and 69% of women versus 84% of men arrived before 9/15. The duration of work for women was the same as men (average 80 days vs. 79 days for men). The majority of women worked adjacent to the pile (65% in September and 64% in January–June). This is a higher proportion than men (47% in September and 54% in January–June). Only 6–8% of women worked on the pile throughout September 2001–June 2002. In general, the activities performed by women responders were not considerably different than men. However, in September, 22% of women reported personnel support activities versus 8% of men; 40% reported security activities versus 30% of men and 28% reported search, rescue and recovery versus 49% for men. This may in part be because more women were in white collar occupations such as media, administrative, healthcare. There was little difference between males and females in the fraction of WTC responders who were volunteers (17% women vs. 14% men).

DISCUSSION

The collapse of the WTC on September 11, 2001 was a major urban disaster that required a complex and extensive recovery effort. Large numbers of responders from multiple occupations were involved in this effort. They performed a myriad of recovery activities, often in stressful and dangerous conditions. This study provides the first comprehensive description of the pre-9/11 occupations, and of the post-9/11 work locations and the types of activities performed by 18,969 responders who enrolled in the WTC MMTP.

Our study showed that the response to the WTC disaster included workers from diverse occupations and backgrounds. Almost one-half of the responders (excluding FDNY fire fighters/EMT’s) belonged to the protective services, primarily police officers and mostly NYPD. However, we found that a large number of workers (>50% of the cohort) were not part of the typical emergency/first responder groups. For example, 22% of the responders were from construction occupations. Due to the major damage to the utility infrastructure in lower Manhattan, a substantial number of workers came from electrical, telecommunications & other installation & repair occupations. Public sector workers comprised more than one-half (61%)of the total responder population and public sector workers were included in all occupational categories. For example, among the construction occupations there were transit and city and municipal workers who are in the construction trades. There were also many other smaller groups of non-traditional emergency responders such as business managers and administrators, clerks, engineers, broadcast and media personnel, social workers, and computer specialists. Although traditional responders receive prior training and have experience in emergency response, other groups were considerably less well prepared for disaster response. Our findings point to the need for prior emergency response planning and training of non-traditional responders who will always be part of a disaster response, such as the groups listed above. Early on-site health and safety training and the provision of appropriate personal protective equipment for these non-traditional responders can minimize potential toxic exposures and decrease the risk of injury during recovery activities.

Assessing the type and extent of exposures is extremely important for understanding potential health consequences among WTC responders. The findings reported herein are a platform for the development of a matrix to characterize exposures among WTC responders. Several previous studies have found that the time of first arrival at the WTC, a crude measure of exposure to the dust cloud from the collapse, is one variable that can provide a temporal differentiation in risk [Banauch et al., 2006; Herbert et al., 2006; Wheeler et al., 2007; Skloot et al., 2009]. In this study, we found that a large number of responders (44%) began work on 9/11, with 46% of them present directly in the cloud of dust from the WTC collapse. Since in this cohort, those who arrived on September 11 were predominately from the protective services group (65%) it is likely that many of them arrived at the site as part of the initial response to the crash of the planes. However, among the remainder of the occupational groups who arrived on 9/11, large proportions also reported being present during the collapse. It should be noted that workers were mobilized from the entire NY/NJ metropolitan area throughout the day after the initial crash and that there were three separate building collapses at different times on that day (the South Tower at 9:59 AM, the North Tower at 10:28 AM and WTC 7 at 5:20 PM).

Most responders (93%) began work in September. This may explain the consistency in the average number of days worked across all occupational groups (72–102 days). In addition, workers in several occupational groups (e.g., construction, electrical, telecommunications and other installation, and repair workers among others) continued work after the time period covered by the exposure assessment questionnaire (end date June 30, 2002).

Due to the added stresses of shift work, it is of particular interest that 48% of the WTC responders reported working both day and night shift even in the period after September, and 3–5% of the responders reporting always or mainly sleeping onsite. By late September, a veritable tent city had grown up adjacent to the pile, with many responder organizations having their own tents [Smith, 2002].

The location and type of the responders’ work are considered an important determinant of potential exposures. Our findings show that the most common work location was “adjacent to the pile” followed by on the “pile or pit,” although this varied for different occupations. Some of the work also occurred in enclosed spaces within buildings and the relationship of indoor exposures compared to outdoor exposures has yet to be assessed. In the future, these factors (timeline, location, indoor vs. outdoor, along with activity) should be combined to create an exposure assessment model that can be used in evaluating health risks among WTC responders.

In examining the geographic and temporal taxonomy of activities, it becomes apparent that in a disaster of the magnitude of the WTC collapse, the crisis response requires most responders to engage initially in search, rescue and recovery, regardless of their pre-disaster occupation. In fact, for most of the occupational groups included in this study, search, rescue, and recovery were the most commonly reported activities during the month of September, 2001. After this initial period, most responders were engaged in activities related to their original, pre-9/11, occupations. Nevertheless, building and grounds cleaning was a commonly reported activity in most occupational groups, due to the wide-spread contamination of dust and debris from the collapse. Because protective services was the most common occupation in this cohort, security work was a very commonly reported activity. The WTC site was considered a crime scene with only authorized personnel allowed access. In addition, this urban disaster was located in a major financial center that also included a dense concentration of residential and commercial properties that remained under heightened security due to a threat of additional terrorist action.

This study provides a comprehensive description of the different groups, work periods, and type of activities performed by a large cohort of responders enrolled in the WTC MMTP. However, NYC firefighters, emergency medical technicians, and short term workers were not eligible for this program and thus, are not represented in this report. Moreover, not all potentially eligible WTC responders have enrolled in the MMTP. Thus, the distribution of occupations may reflect in part the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the WTC MMTP. Data for our study were obtained from answers to a standardized questionnaire routinely administered as part of the initial visit to the WTC MMTP. Although the exposure assessment survey includes detailed questions about activities, dates, times, and locations of work, the information is based on self-reports and thus, potentially subject to recall and other types of biases.

Another limitation in our data is related to the use of the SOC groups to describe a responder’s pre-9/11 occupation. Unfortunately, the SOC groups often combine relatively different occupations within a single category. However, this is a validated system to classify workers and is one of the most commonly employed coding systems in the literature as well as in the National Health Interview Survey.

The structure of the MMTP questionnaire restricted some analyses. For example, activity information was collected for four time periods and the location of the majority of the responders work during each time period was assessed separately. As a consequence, we are unable to make a direct link between each task and a specific location. Instead we have assumed that the activities reported during a time period occurred at the location reported by the responder as the site they spend the majority of their shift during the time period. Similarly, there was no information collected about activities on a daily basis following the collapse of the twin towers. This information would have allowed us to describe in further detail how activity patterns changed as the WTC site transitioned from crisis response to the subsequent recovery phase. Additionally, the WTC exposure questionnaire is limited to activities performed through June 30, 2002. However, work in some occupations, such as telecommunications, construction and at some sites, such as the Fresh Kills landfill, continued well beyond this date.

Despite these limitations, the exposure assessment questionnaire provides a great deal of insight into the work done by responders to the WTC disaster. The large cohort size and the detail available from the questionnaire provide the most comprehensive description to date of the non-FDNY WTC responder population. Based on post-9/11 experiences at the WTC site and surrounding areas, as well as on experiences gained in the aftermath of hurricane Katrina, the BP oil disaster in the Gulf, as well as the tsunami and nuclear reactor disaster in Japan, the definition of a disaster responder has become much broader and responders should be understood to include not only conventional emergency responders involved in the immediate response to the crisis, but also those workers who participate in the restoration of vital services and recovery activities which may last for years [Bradt, 2003]. This recognition makes planning for health, safety, exposure assessment, and protection of all workers in the aftermath of a disaster much more complex than previously conceived [Bradt, 2003].

CONCLUSION

Our analysis described the spatial, temporal, occupational, and task-related taxonomy of the responders enrolled in our program. This study shows that the response to the WTC disaster included a large number of traditional as well as non-traditional workers, most of whom arrived early after the collapse of the towers and were involved in numerous recovery activities at multiple locations over time. The most common pre-9/11 occupation in our program was protective services (47%), but many were non-traditional responders (construction, telecommunications, transportation, and support services workers), and 14% worked as volunteers. Public sector workers comprise 61% of the total responder population enrolled in this cohort. Almost one-half began work on 9/11and >80% reported working on or adjacent to the “pile” at Ground Zero. Initially, the most common activity was search and rescue but subsequently, the activities of most responders related to their pre-9/11 occupations. Other major activities included security; personnel support; buildings and grounds cleaning; and telephone, cable, and computer repair. The results will aid development of a job-exposure matrix, assist assessment of disease risk and improve planning for future urban disasters.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Hovi Nguyen for making the maps used in this paper.

Contract grant sponsor: Centers for Disease Control and NIOSH; Contract grant numbers: UIO 0H008232; U10 OH008225; U10 OH008239; U10OH008275; U10 OH008216; U10 OH008223;

Contract grant sponsor: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (CDC/NIOSH); Contract grant number: 200-2002-0038.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (CDC/NIOSH).

Disclosure Statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- Banauch GI, Hall C, Weiden M, Cohen HW, Aldrich TK, Christodoulou V, Arcentales N, Kelly KJ, Prezant DJ. 2006. Pulmonary function after exposure to the World Trade Center collapse in the New York City Fire Department. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174:312–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellew MJ. 2004. Clearing the way for recovery at Ground Zero. American Public Works Association Reporter. [Google Scholar]

- Bradt DA. 2003. Site management of health issues in the 2001 World Trade Center disaster. Acad Emerg Med 10:650–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics USDoL. 2000. Standard Occupational Classification 2000. [Google Scholar]

- CNN. 2001. September 11: Chronology of terror. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert R, Moline J, Skloot G, Metzger K, Baron S, Luft B, Markowitz S, Udasin I, Harrison D, Stein D, Todd A, Enright P, Stellman JM, Landrigan PJ, Levin SM. 2006. The World Trade Center disaster and the health of workers: Five-year assessment of a unique medical screening program. Environ Health Perspect 114:1853–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jederberg WW. 2005. Issues with the integration of technical information in planning for and responding to nontraditional disasters. J Toxicol Environ Health A 68:877–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioy PJ, Gochfeld M. 2002. Lessons learned on environmental, occupational, and residential exposures from the attack on the World Trade Center. Am J Ind Med 42:560–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerwitz J. 2006. Aftermath: World Trade Center archive. New York: Phaidon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moline JM, Herbert R, Levin S, Stein D, Luft BJ, Udasin IG, Landrigan PJ. 2008. WTC medical monitoring and treatment program: comprehensive health care response in aftermath of disaster. Mt Sinai J Med 75(2):67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J. 2009. Estimating the World Trade Center tower population on September 11, 2001: A capture-recapture approach. Am J Public Health 99:65–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: Final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. Washington, D.C.: Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O. [Google Scholar]

- Reissman DB, Howard J. 2008. Responder safety and health: preparing for future disasters. Mt Sinai J Med 75(2):135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz DA, Oxman RT, Metzger KB, Wallenstein S, Stein D, Moline JM, Herbert R. 2008. Epidemiologic research on man-made disasters: Strategies and implications of cohort definition for World Trade Center worker and volunteer surveillance program. Mt Sinai J Med 75:77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skloot GS, Schechter CB, Herbert R, Moline JM, Levin SM, Crowley LE, Luft BJ, Udasin IG, Enright PL. 2009. Longitudinal assessment of spirometry in the World Trade Center medical monitoring program. Chest 135:492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. 2002. Report from ground zero: The heroic story of the rescuers at the world trade center. New York: Viking Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler K, McKelvey W, Thorpe L, Perrin M, Cone J, Kass D, Farfel M, Thomas P, Brackbill R. 2007. Asthma diagnosed after 11 September 2001 among rescue and recovery workers: Findings from the World Trade Center Health Registry. Environ Health Perspect 115:1584–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.