Abstract

Tourism universally generates benefits and costs to the destination and community. Knowledge on the impacts of tourism on local communities provides important insight in formulating strategies for long term sustainable tourism. Therefore, there is a need to evaluate the impacts of tourism before establishing/expanding the industry at a particular destination. In this study, we assessed the economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits of tourism in a remote mountainous village that experiences the high pressure of tourism activity. Data were collected for the perceived and anticipated social, economic, and environmental costs/benefits of tourism via in person interview with local residents, hotel owners, and local governmental bodies through unstructured questionnaire survey. The data were analysed using a Leopold matrix. The result revealed that tourism generates noteworthy economic and social benefits to the destination community, while environmental benefits are not obvious. The negative impacts in all the three aspects are minimal and within the threshold limit. Our quantitative assessment revealed that the net impact of tourism in Ghorepani is impressively positive (>40%). The findings of this result thus suggest that tourism is the most lucrative industry of Ghorepani and its further promotion can contribute to the broader enhancement of social and economic status of the village. This finding may have greater implications beyond the case study, and suggests that tourism if extended as the primary industry in other similar mountainous villages can play a pivotal role to enhance the socio-economic status of the country. Thus, the current findings provide important insights in formulating plans and policies for the management of sustainable tourism across the mountainous destinations.

Keywords: Economy, Ecotourism, Rural tourism, Sustainable tourism, Tourism impact

Economy; Ecotourism; Rural tourism; Sustainable tourism; Tourism impact.

1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the most important socio-economic phenomena of the 21st century (WTO, 2016). Due to the potentiality of rapid expansion of the industry associated with the high tendency of visitors to visit new destinations, it has been considered as one of the biggest and fastest growing labour-intensive industries in the world (WTO, 2016; Zurick, 1992). It generates multiplier effects on the destination and community and thus it has been considered as the backbone of economic and social development in many countries (Mayer and Vogt, 2016; Ridderstaat et al., 2013). Due to the growing tendency of the visitors to seek out new tourism destinations focusing on their personal preferences, tourism industry has experienced tremendous expansion and diversification in the last few decades. The intensive growth of tourism industry not only generates social, economic, and environmental benefits (Almeida-García et al., 2015; Dyer et al., 2007; Hernandez et al., 1996; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009) but also imposes several negative impacts on the destination community (Haralambopoulos and Pizam, 1996; Ko and Stewart, 2002; Sequeira and Nunes, 2008; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009). Indeed, depending upon the several factors associated with the destination/visitors, tourism can be an ally or threat to a particular destination (Allen et al., 1988; Balmford et al., 2009; Butler, 1980; Deguignet et al., 2014). In some instances, the negative impacts of tourism are intangible and outweigh the positive benefits (Besculides et al., 2002; Dwyer and Forsyth, 1993; Mikayilov et al., 2019; Pickering et al., 2018). When negative impacts outweigh the positive benefits, tourism could induce several intangible social and economic crisis. Moreover, even for the same destination, the impact of tourism may vary temporarily and spatially (Besculides et al., 2002; Dyer et al., 2007; Haralambopoulos and Pizam, 1996; Mathieson and Wall, 1982). These facts underlie the need to assess the potential benefits/costs of tourism before the establishment/expansion and diversification of the industry to a particular destination.

Globally, in the last few decades there is growing tendency of visitors to explore the destinations focusing on adventures and great natural patrimonies. This tendency of visitors led to the substantial expansion and diversification of tourism; consequently, a new form of tourism arose known as ecotourism (Riveros and Blanco, 2003; WTO, 2002). In ecotourism, the visitors’ main motive is observation and appraisal of nature and traditional culture prevalent in the community (WTO, 2002). Thus, Nepal, a country of diverse natural beauty and traditional culture, has been one of the touristic spotlights of the world.

The tourism in Nepal has a long history from the time immemorial, however, Nepalese tourism got explored to the world arena only after the unification of Nepal by Prithvi Narayan Shah (Satyal, 1988). The tourism in Nepal, despite having its long history of development, had only been considered as a significant industry since 1959, following the advent of democracy (Upadhyay and Grandon, 2006). Since then, Nepal opened its door to foreigners with the aim of developing tourism industry in the country. Various activities organized by the government in the decade 1950–1960 AD not only contributed to introduce Nepal to the world arena but also created a substantial increase of foreign tourists in Nepal (Shrestha and Shrestha, 2012).

With the advent of gradual increase in the number of tourists in Nepal, Nepal government perceived that tourism could be one of the prominent industries to uplift the economy of the country. Accordingly, to attract tourists from around the globe, the government of Nepal promulgated several policies and plans such as (i) Tourism Master Plan 1972, (ii) Celebrating the year 1998 as “Visit Nepal 98” to further enhance the image of Nepal as a special destination for the visitors, (iii) Celebrating the year 2011 as “The Tourism Year 2011” with the aim of bringing 10,00,000 foreign tourists to the nation, and (iv) Celebrating ‘Visit Nepal 2020’ (but cancelled due to the pandemic outbreak of COVID-19 from the very beginning of the year 2020) with the main objective of increasing annual international tourist arrival to two million and augmenting economic activities and employment opportunities in tourism sector to one million. The current tourism policy of Nepal (GON, 2008) aims to increasing national productivity and income, increasing foreign currency earnings, creating employment opportunities, and improving regional imbalances by augmenting the magnitude of tourism activities via reinforcing Nepal as an attractive, beautiful and all-season safe destination in the international tourism map (MoTCA, 2008; NPC, 2010). These outstanding plans and policies not only revitalized the tourism activities but also contributed to establish tourism as one of the important industries in Nepal (Shrestha and Shrestha, 2012). Now, Nepal has been regarded as one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world for all kinds of tourists including trekkers, mountaineers, nature lovers, bird watchers, adventure seekers and religious tourists.

In the recent year, there has been rapid increase in tourism activity throughout the country. Over the period of last 10 years (2009–2018), the tourist arrivals have nearly been doubled (MoTCA, 2019). Thus, in the recent days, tourism has provided great contribution to the GDP of Nepal through foreign exchange earnings and generating employment opportunity (Paudyal, 2012). At present, this industry provides direct employment opportunity for 138148 people (Bhandari, 2019) while total employment provided by this sector reaches to 1034000, constituting 6.9% of total employment in the country (WTTC, 2019).

The tourism policy of Nepal aims to establish ecotourism as the primary industry in the several mountainous destinations across the country. Accordingly, expansion of existing tourism industries and establishment of new tourism destinations in the mountainous regions across the country have been the major focus of both the government and private sectors. In the recent days, as in the global context, there has been an exponential increase in nature-based tourism in Nepal. The tourist arrival data of the last 10 years indicate that mountain tourism is the most prominent product of Nepal. Thus, in the recent years, the mountainous villages across the county are experiencing the high pressure of tourism activity. The increased tourism activity in the rural villages not only brings positive benefits but also likely to impose several costs to its unique culture and fragile ecosystem. Particularly, tourism in the mountainous region suffers from different costs because of several technical issues such as difficulties for the expansion of road and other infrastructures, difficulties in transport, potential calamities like landslide, erosion associated with fragile landscape, and loss of native biodiversity. Mckercher (2003) and Kisi (2019) suggest that tourism could be established as a sustainable industry only by maintaining sustainability in the four major disciplines i.e., economic sustainability, ecological sustainability, cultural sustainability, and local sustainability of a destination. Thus, it is imperative that any kind of tourism should not adversely affect the available resources and the benefits of the present should not compromise with that of future. These facts underlie the need of a comprehensive study before expanding/establishing tourism industry in the mountainous regions. The findings of such comprehensive studies would provide valuable insights in formulating mountain tourism policy.

In the global context, plethora of studies incorporating the impacts of tourism do exist in tourism literature (Allen et al., 1988; Almeida-García et al., 2015; 2021; Balaguer and Cantavella-Jordá, 2002; Besculides et al., 2002; Butler, 1980; Comerio and Strozzi, 2019; Dwyer and Forsyth, 1993; Greiner et al., 2004; Haralambopoulos and Pizam, 1996; Kozhokulov et al., 2019; Lepp, 2007; Liu and Li, 2018; Maldonado-Oré and Custodio, 2020; Mathieson and Wall, 1982; Mcdowall and Choi, 2010; Mikayilov et al., 2019; Nepal, 2000; Nepal et al., 2002; Nunkoo and Gursoy, 2012; Pickering et al., 2018; Shih and Do, 2016; Truong et al., 2014; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009). The crux of the findings of these studies suggests that negative impacts should not be overlooked while establishing/expanding tourism industry at a destination.

In the context of Nepalese tourism, only a handful of qualitative studies do exist (Baral et al., 2012; Baral, 2015; Bhandari, 2019; Burger, 1978; Chan and Bhatta, 2021; Gurung, 1991; Karki, 2018; Nyaupane et al., 2014; Pandey et al., 1995; Stevens, 2003). Moreover, these studies are focused assessing either the positive impacts or negative impacts only. Although the findings of these previous studies provide meaningful theoretical insights, they are insufficient to provide explicit evidence on the net impact of tourism, and those findings may not be universally applicable across the different destinations as the impact of tourism may vary by time, space and level of tourism development (Allen et al., 1988; Butler, 1980; Dwyer and Forsyth, 1993; Greiner et al., 2004; Liu and Li, 2018; Mathieson and Wall, 1982; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009). As quantitative studies evaluating the net impact of tourism are meagre in the Nepalese context, there is a need of comprehensive studies which would not only make a significant contribution towards expanding the limited literature on the impact of tourism in the Nepalese context but also provide insights on the role of tourism in the development of the country and the people as a whole.

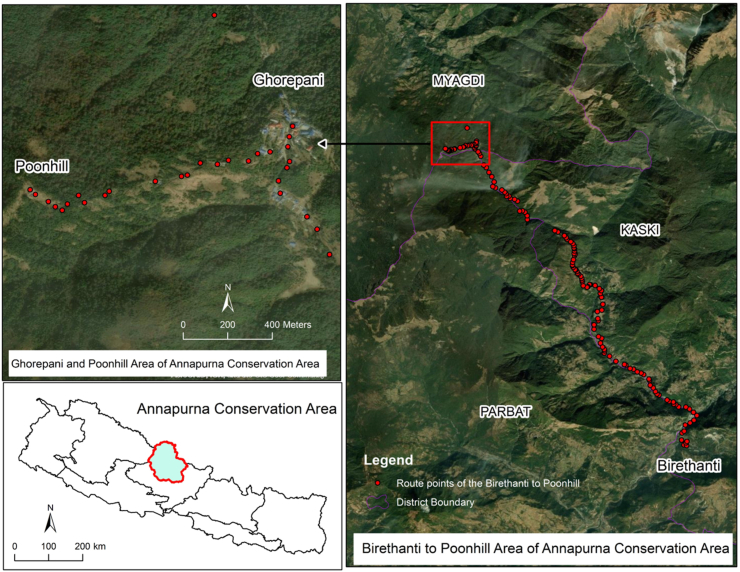

In this study, we assessed the net impact of tourism in Ghorepani, one of the most widely trekked mountainous destinations of Nepal (Nepal et al., 2002; PTC, 2008). The village is famous among the visitors not only as a trekking destination but also as a centre of traditional culture as it offers a unique blend of the typical Gurung and Magar culture in rural setting. The village is a part of Annapurna Base Camp trekking route and is one of the accommodation places for the trekkers of the Annapurna trekking circuit. It can be reached through one of the easiest and safest trekking routes in the country (Figure 1), and thus it has been established as one of the ten most popular trekking destinations in the world (Nepal et al., 2002; PTC, 2008). Moreover, Ghorepani is the only one gateway and accommodation place for the visitors of Poonhill, a small alpine meadow located at 3210 m that is popular among the visitors as a view point for observing the panoramic view of the Himalayas (Figure 2). Therefore, almost all the visitors of Poonhill at the very least spend a single night at Ghorepani. Furthermore, this village is the main destination for short haul trekkers, trekkers travelling to mustang, and for those trekkers passing through Thorang-La pass in Mustang in their trekking journey from Manang to Pokhara. The village links many rural villages as well as the several trekking routes of the famous tourist destinations. Due to these specific features, this destination receives half of the country’s total trekking tourists (Baral et al., 2012; Buckley, 2003). During the peak season there is a very high demand of accommodation place, and thus the numbers of hotels at Ghorepani are being increased every year. Hence, this destination is experiencing the high pressure of tourism activity. In the current scenario, the livelihood and the entire economy of Ghorepani are intricately connected to tourism as it provides service/job opportunity to the entire community. Thus, the local residents predominately acknowledge only the positive benefits of tourism while the negative impacts of tourism have never been the matter of consideration. Although, the residents of Ghorepani are not much concerned with the potential negative impacts of tourism, the increased tourism activity in this rural village not only brings positive benefits but also likely to impose several costs to its unique culture and fragile ecosystem. Moreover, this destination is recently facing rural road expansion which is likely to replace the long-established trekking activities of the village. Therefore, to ensure the long-term sustainability of the tourism industry, the impacts of tourism should be properly monitored, assessed and managed (Das and Chatterjee, 2015; Dwyer and Forsyth, 1993; Greiner et al., 2004). These facts underlie the need of a comprehensive evaluation of the potential negative/positive impacts of tourism, and to assess the potential impact of rural road expansion on the trekking tourism of Ghorepani. The insight gained from such comprehensive study not only provides information about the benefits as well as the negative impacts that tourism could generate on the society, economy, and the environment but also evaluates whether tourism could be the appropriate sustainable industry of the destination or not. Here, we specifically addressed the following questions: (i) What are the social, economic, and environmental benefits of tourism? (ii) What are the social, economic, and environmental costs of tourism? (iii) Does tourism generate net benefit? (iv) Does tourism provide equitable benefits to the wider community of the destination? (v) What are the potential impacts of rural road expansion on the tourism activity? The findings of this research contribute substantially in promulgating effective management plans/policies with long-term sustainability goals for expanding/establishing tourism industry across the other mountainous destinations of Nepal.

Figure 1.

Geographical details of the study site. A-The trekking route to Ghorepani from Birethati, B- Ghorepani village and its location, C- Trekking route from Ghorepani to Poonhill. The satellite images were extracted from Google Earth (https://earth.google.com).

Figure 2.

A -The entrance gate to Ghorepani, B - the trekking trail to Poonhill from Ghorepani, C - Visitor’s Park area and the view tower of Poonhill, D - The panoramic view of the Himalayas observed from the Poonhill. All the photos used in this figure are taken by the first author.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical approval

Before conducting experiment, ethical approval was taken from the executive council of Annapurna Rural Municipality, Myagdi and Hotel Association of Ghorepani. While conducting interview survey and group discussion, Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) was taken from all the respondents.

2.2. Study site

The study was conducted in Ghorepani, a remote mountainous destination in Nepal. Ghorepani is a small rural village in Myagdi district, Gandaki province with about 50 households. The village is located at an altitude of 2874 m from the sea level, and lies within the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP). It can be reached via two routes only by trekking as the village currently does not have access to motorable roads. Of the two routes, Birethati-Ghorepani trekking route located in the south-east direction of the village is most popular. Through this route (Figure 1), the village can be reached by foot from the village Birethati in about 10 h. This trekking route is probably one of the easiest and safest trekking routes in the country and thus Ghorepani has been established as one of the ten most popular trekking destinations in the world (Nepal et al., 2002; PTC, 2008).

2.3. Tool for impact assessment

Various approaches, both qualitative and quantitative, are in practice to evaluate the impact of tourism on a destination (Kozhokulov et al., 2019; Kumar and Hussain, 2014). However, each of the currently used methodologies suffers from their own advantages and disadvantages (Canteiro et al., 2018; Kumar and Hussain, 2014). Here, we adopted the tourism impact assessment (TIA) method developed by Canteiro et al. (2018) to estimate the impacts of tourism at Ghorepani. Although, this method was originally developed to estimate the environmental impacts of tourism, considering its wide applicability and several advantages over the other traditionally used approaches (Canteiro et al., 2018), we adopted this method for this study. This approach involves four sequential steps: (i) identification of pressure, (ii) selection of impact components, (iii) identification and description of impacts, and (iv) establishment of criteria to evaluate the magnitude of impacts.

For the identification of pressure, we adopted observation and consultation method. We observed the various touristic activities in the study area. In addition to our observation, we conducted interviews and group discussion to identify the touristic activities that generate pressure on the community and environment. Based on our observation and assessment, and the views of the local residents, we identified the length of stay as the impact determining factor (pressure). We included various social, economic, and environmental factors that could be potentially affected by the touristic activities as the impact components. The impact of each touristic activity (pressure factor) on each impact component was estimated through a Leopold Matrix of pressure vs components. The Leopold matrix is an interactive matrix that was first designed to evaluate the environmental impact of a project/activity in a particular destination (Josimovic et al., 2014; Leopold et al., 1971). However, Leopold matrix is flexible and has wider applicability to a broad spectrum of circumstances (Canteiro et al., 2018; Leopold et al., 1971). Thus, we used this approach to assess the impact of tourism in the various social, economic, and environmental factors, and to estimate the net impact of tourism in Ghorepani. The magnitude of impact depends upon the pressure severity, components vulnerability, threshold capacity of the destination, and the management capacity of the stakeholders (Canteiro et al., 2018). So, these factors were considered as the criteria to evaluate the magnitude of impact on each factor.

2.4. Research design and method of data collection

The present research was based on the primary data collected via group discussion, personal interview, and questionnaire survey with the stakeholders and local residents, and field visit’s observation and assessment. For the group discussion, personal interview, and questionnaire survey, employee/executive of the local governmental body, entrepreneurs and employee of the tourism industry, and local residents were considered as the key respondents. The respondents were then categorized into three groups (local governmental bodies, entrepreneurs and employee of the tourism industry, and local residents). The respondents from the second and the third group were selected by random sampling method while the respondents of the first group were selected in a way if he/she has the authority to provide authentic detailed information as indicated in the questionnaire survey. Annapurna rural municipality (Myagdi) was considered as the local governmental body, the first type of respondent. The entrepreneurs and the employees of the tourism industry (hotels, restaurants, and other tourism related business) were considered as the second type of respondents. Local residents of Ghorepani who are not directly involved in tourism business were considered as the third type of respondents. All the respondents were informed that the collected information will be used only for this research and they were also assured that their identity will not be disclosed anywhere. To make the interview comfortable, the interviews were taken in the local language (questionnaires were translated into Nepali) at the interviewee’s work place/home. The first round of data collection was done from March through October in 2019. We repeated the assessment from March through May 2022.

Three different sets of unstructured questionnaires (Supplementary file: Tables S1, S2 and S3) were prepared targeting for the three different groups of respondents and the specific set of questionnaire was asked for each of the three different groups of respondents. The use of unstructured questionnaire allows the respondents to openly provide their views without limiting themselves to the framework of structured questionnaire, and thus it ensures the better understanding of key issues of tourism from the respondents (Hernandez et al., 1996; Lepp, 2007). The questionnaires were designed to characterize the perceived and anticipated impacts of tourism on social, economic, and environmental sectors and consisted of two major sections. The first section of the questionnaire contains a few miscellaneous open-ended questions in which the respondent can provide their personal data/view about the tourism industry of Ghorepani. The second section of the questionnaire contains the impact assessment questions in which the respondents are required to provide their assessment score on a range of −1 to −10 and/or 1 to 10 where the scores between 1 to 10 indicate positive impact with 1 the least benefit and 10 the most, while scores from −1 to −10 represent the negative impact with −1 the least effect and -10 the devastating effect. The respondents were urged to evaluate the magnitude of impact on each factor by following the criteria developed in subsection 2.2, i.e., by integrating the pressure severity, components vulnerability, threshold capacity of the destination, and the management capacity of the stakeholders.

The data on the costs and benefits of tourism were categorized as (i) social benefits/costs, (ii) economic benefits/costs, and (iii) environmental benefits/costs. The economic costs and benefits were estimated based on the (i) Costs and benefits of the government sector. Here, the revenue generated from the tax and user fee were considered as the economic benefits while the expenses of the government (the expenses on repair and renovation of physical infrastructures, and the expenses on the promotion, security, and health) were considered as the costs, and (ii) Cost and benefits for the stakeholders (such as entrepreneurs and employees of tourism business). For the stakeholders, jobs, service, trade, and revenue generated from the tourism, additional employment, and income were considered as the economic benefits while the equity depreciation, job seasonality, and inflation were considered as the cost. The social costs and benefits were evaluated based on the costs and benefits for the society (residents of the study area and its physical surroundings). For this, the overall development (physical, cultural, cognitive) of the society, opportunity for health and security, and opportunity for recreation were considered as the benefit while problems emerged in the society due to tourism (degradation of language, culture, education, religion, and the loss of traditional knowledge and skill) were considered as the cost. The positive impacts generated by tourism activity for the protection of natural environmental were considered as the environmental benefits, while the negative effects on environment were considered as the environmental costs. Any specific efforts/policies of the local government, stakeholders, and the local residents to conserve the environment and their positive consequences were evaluated as environmental benefits. The environmental costs of tourism were determined by assessing the impacts on air (smell, dust), soil (erosion, compaction, solid residue), water (solid residue), and plants (damage on plants along the walking trails, observational sites, and around the hotels). The solid residues were collected from along the walking trails, observational sites, and around the hotels. The collected residues were then categorised as organic and inorganic residues and quantified separately. Because the organic residues are biodegradable, they were not considered as pollutants and thus excluded for further analysis. As the solid residue generated in the hotels were managed by the hotel owners, we were unable to quantify the hotel generated solid residue. The data on this type of solid residue were collected via personal interview with the hotel owners.

In addition to the questionnaire survey, group discussion, and personal interview, we also adopted the field observation method to evaluate the impacts of tourism in Ghorepani. During a month extensive field study, we closely observed the community to deeply assess the impacts of tourism on the various economic and social aspects. To assess the impact of tourism on the economic and social aspects over the last fifty years, we interviewed people from different age groups and generations (aged from 15 years to 80 years). To confirm that the impact seen in Ghorepani are due to tourism activity, we evaluated the social and economic parameters in another rural village (Sidhnae, Kaski) that is similar to Ghorepani in every aspect (offers a great view of the Himalayas, 5–6 h’ trek from the nearby city, no reliable road facility, similar natural landscape, and the residents adopting the same Gurung culture) but does not have tourism activity. We then compared the differences in the social and economic status of the two villages.

2.5. Data analysis

We assessed the subjective evaluation of the respondents on the various economic, social, and environmental factors, i.e., the responses obtained through section A of questionnaire survey, following the above derived criteria, and the responses were transcribed into quantitative scores in the range of ±1 to 10. Here, following the above derived criteria, we considered the length of stay as the impact determining factor (pressure) and the values (±1 to 10) were scored based on the magnitude of impacts the three tourism activities (i.e., length of stay) generate on the several social, environmental, and economic factors (components). These responses were further evaluated in the range of ±1 to 10 by three experts of three various fields: ecology and biodiversity expert, environmentalist, and tourism expert. The experts were also urged to follow the above derived criteria while evaluating the magnitude of impacts. Finally, the quantitative scores (±1 to 10) obtained through key respondents, our own assessment, and the assessment of the expert were integrated together, and their mean values were used for the further analysis.

At the end, a Leopold matrix consisting of visitors’ activities (pressure) and various social, environmental, and economic factors (impact components) on the two different axes as the cause-effect factors was developed to evaluate the magnitude of impacts (costs and benefits) of tourism activities for each parameter. The social, economic, and environmental costs/benefits were separately evaluated, and finally the net impact (costs/benefits) of tourism was evaluated based on the net benefits/costs to the social, economic and environmental factors.

3. Results

The result obtained from the questionnaire survey revealed that destination populations recognized only economic benefits in terms of service and job creation. They were not aware of any other benefits either economic/social that tourism has been generating in the destination. Moreover, most of the respondents (n = 53) did not acknowledge any negative impacts of tourism. Most of the respondents stated that “tourism has been a boon not only to the local residents but also to the neighbouring community, and we do not perceive any negative impacts of tourism”. However, our assessment, based on the one-to-one communication or group discussion with the local residents, revealed several social and economic benefits and costs to the destination community which has been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Perceived and anticipated Economic and Social impacts of tourisms at Ghorepani as revealed by field visit’s observation and assessment, group discussion, personal interview, and questionnaire survey with the stakeholders and local residents.

| Economic | Social | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Impacts | Benefits | The source of foreign exchange earning | Higher opportunity for health and security |

| Improved economic status of the community | Improved living standard/Improved shopping | ||

| Job/service creation Increased price of local products Increased wages for labourers |

Opportunity for learning foreign language and culture Improved opportunity for infrastructure development. |

||

| Improved opportunity for the trade of local products | |||

| Costs | Job seasonality/unsustainable employment | Tolerable impact on traditional language, culture, and religion | |

| Inflation Increased cost for transportation Increased cost for repair and maintenance of appliances |

Over exploitation of cultivable land for tourism activity Changes in the pattern of settlements, loss of traditional architecture Decreased community cohesiveness |

||

| Anticipated Impacts | Benefits | Further promotion of the place for both domestic and international tourists creates more job and service. Thus, tourism can be established as a key industry of this destination. This may ultimately enhance the economy of the country as a whole | Tourism promotion may resolve the unemployment problem of the province and the country as a whole |

| May increase intercultural social interactions | |||

| May introduce this destination across the globe | |||

| Costs | Expansion of road may cause the loss of job/service of trekking related personnel. | Expansion of motorable road in the fragile destination may lead to natural calamities. | |

| Further expansion of tourism may attract big corporation which may replace the small-scale investment of local people. Thus, economy may be polarized. | Traditional entrepreneurs may lose their business, and thus their livelihood may be badly affected. | ||

| High degree of dependency on tourism may further spoil the community cohesiveness leading to the polarization of society. |

We found the forest degradation linked with the demand for fuel wood and timber, encroachment on the forest as well as on the private agricultural land, garbage along the walking trails, and land use changes as the major noticeable negative environmental impacts of tourism. However, none of these impacts were severe. Our observation revealed that some of the visitors (specifically domestic visitors) were freely plucking the flowers of Rhododendron and dumping the solid waste indiscriminately along the trekking routes. Plastics wrappers, water bottles, glass bottles, metal cans, and cigar filters were the inorganic residues collected from along the walking trails and observation sites, while organic residues were not observed. The net weight of inorganic residue collected from along the Ghorepani-Poonhill trail was less than 1 kg, while the average daily weight of the residue at the observation sites (Poonhill) was 1.4 kg (5 days). The inorganic residues collected at the observation site were burnt indiscriminately. This practice though destroyed the combustible residues, the fragments of glasses and metal cans remained as such. Thus, these residues were found accumulating since many years. We found, through our questionnaire survey, that average daily weight of inorganic residue generated at a hotel was between 1 and 5 kg. Likewise, the average daily weight of organic residues generated in a hotel was between 2 and 10 kg. We found that the organic residue generated at the hotels were decomposed either by burying or fed to the domestic animals, while the inorganic residues were either burnt (plastics and other combustible residues) or buried under the ground. Like the land, water bodies were also found contaminated by solid wastes while impact on air was not detected. Likewise, excluding the flowers plucking by some visitors, the impacts on plants were also meagre. Thus, despite the very high intensity of tourism activity in this area, in the current context, the negative impacts of tourism to the environment were negligible.

We found that the conservation area in collaboration with the local residents and tourism office has set a number of garbage disposing spots along the trekking trail and in the village. Beside collecting and disposing the garbage, there were no any specific regulations to protect the environment/biodiversity of Ghorepani. Therefore, there were no environmental benefits of tourism in Ghorepani.

The quantification of the impact of tourism revealed that among the seventeen evaluated factors (Table 2), eight are positively impacted while nine are negatively impacted. Interestingly, the magnitudes of impact for the positively impacted factors (except opportunity for recreation), were in the upper range (≥5). On the contrary, the magnitudes of impact for all the nine negatively impacted factors were in the lower range (≤−3). Among the three tourism activities, the positive impact remains almost the same, while the negative impacts differed slightly with long stay tourism generating relatively higher negative impact than one-day tourism. We found that the trekking activity with one-night stay generated the highest net impact (42% of the total impact) relative to the net impact generated by leisure tourism (35%) and/or tourism with professional stay (22%). Thus, it reveals that Ghorepani should be promoted as a short haul trekking destination rather than a destination of leisure tourism. The reduced and modified Leopold matrix revealed the net positive impact of tourism on both the factors, i.e., socio-environmental factors and economic factors. We found that, although both the factors were positively impacted by tourism, the net economic impact was much higher (94.7%) than the social impact (5.3%). The estimation of net impacts of tourism revealed an outstanding positive benefit of tourism (44.3%) in the study site (Table 2). Moreover, our comparative assessment revealed the much higher social and economic status of Ghorepani than Sudhame. This suggests the very high positive impact of tourism in Ghorepani.

Table 2.

Modified Leopold Matrix for assessing the net impacts of tourism in Ghorepani.

| Cost-Benefit factors | Visitors Action |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trekking/one night stay | Leisure tourism (Stay for <1 week) | Professional stay (>1 week) | Negative impact | Positive impact | Net impact on sub factors | Average impact on sub factors | Average impact on factors | Net impact of tourism | Net impact by factors (%) | ||

| Social and environmental costs and benefits | Culture | −1 | −2 | −4 | 0 | 3 | −7 | −2.33 | 0.234 | 4.43 | 5.3 |

| Language | −1 | −2 | −4 | 0 | 3 | −7 | −2.33 | ||||

| Education | −1 | −3 | −5 | 0 | 3 | −9 | −3 | ||||

| Traditional skill | −1 | −2 | −3 | 0 | 3 | −6 | −2 | ||||

| Life style | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 5 | ||||

| Religion | −1 | −2 | −6 | 0 | 3 | −9 | −3 | ||||

| Recreation | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 3 | ||||

| Infrastructure | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 5 | ||||

| Health and Security | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 5 | ||||

| Environment | −2 | −3 | −4 | 0 | 3 | −9 | −3 | ||||

| Economic costs and benefits | Equity depreciation | −2 | −2 | −2 | 0 | 3 | −6 | −2 | 4.19 | 94.7 | |

| Job creation | 8 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 26 | 8.66 | ||||

| Job seasonality | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 3 | −3 | −1 | ||||

| Service creation | 8 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 26 | 8.66 | ||||

| Inflation | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 3 | −3 | −1 | ||||

| Trade | 8 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 24 | 8 | ||||

| Revenue generation | 8 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 24 | 8 | ||||

| Positive Impact | 8 | 8 | 8 | 24 | |||||||

| Negative Impact | 9 | 9 | 9 | 27 | |||||||

| Impact by Visitor’s action | 39 | 34 | 22 | ||||||||

| Impact by Visitor’s action (%) | 42 | 35 | 23 | ||||||||

The assessment revealed that more than 95% residents of Ghorepani are directly involved in tourism business. The remaining residents were also directly benefited from tourism as they sell their products in the local market at a higher rate which they would have to take a very far market had there been no tourism. Moreover, they also get seasonal jobs during the peak season. Thus, the result revealed that tourism at Ghorepani provides equitable benefits to the wider community.

Our assessment revealed that rural road expansion induced landslide, erosion, uprooting of tress, destruction of pasture land, and deforestation, which directly/indirectly obstruct the trekking route and deteriorate the natural beauty of the site. Besides these directly observed negative impacts, we, based on the response of the local residents, revealed that rural road expansion would diminish the trekking tourism of this area. Thus, rural road expansion induced negative impacts on the tourism activity of Ghorepani.

4. Discussion

In the past, subsistence agriculture, animal rearing, and hunting in the wild were the primary occupation of the local residents at Ghorepani (Pers. Comm.: local residents). Following the advent of democracy in 1951, Nepal opened its door for international tourists by emphasizing the decade (1950–1960 AD) as the mountain tourism decade. In this decade (1950–1960 AD), seven of the eight over-8000 m peaks in Nepal were successfully scaled, the first over-8000 m peak was successfully conquered (on June 3, 1950 Annapurna I was ascended by French citizens Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal), and the world’s highest peak Mount Sagarmatha (Everest) was successfully ascended by a Nepalese Tenzing Norgay Sherpa and New Zealand citizen Sir Edmund Hillary on May 29, 1953. These events greatly publicized Nepal as the top destination for the mountaineering activities (Shrestha and Shrestha, 2012). With the advent of mountain tourism in Nepal, Ghorepani (a part of the Annapurna base camp trekking trail) also started to receive foreigner trekkers and mountaineers. Now, this destination has been established as one of the safest and easiest trekking routes in the tourism map of Nepal (NTB, 2003). Thus, Ghorepani started to receive foreign trekkers and mountaineers, and the local residents were gradually attracted towards tourism occupation. In the recent days, there has been a rapid growth of tourism activities in Ghorepani. The rapid expansion of tourism has provided an alternative economic activity to the local resident, and thus the traditional occupations have almost jeopardised. At present, the livelihood of the residents at Ghorepani has been entirely dependent upon tourism, and thus the stakeholders such as local residents, communities and the governmental bodies have shown great interest for the expansion of tourism in this area.

Tourism at Ghorepani is entirely based on nature and culture. As a large proportion of tourism in Nepal constitutes the nature and culture-based tourism (Bhandari, 2019), each year there is tremendous increase in tourism activities in Ghorepani. During the peak season (October–November, and March–April) the flow of tourists is so intense that all the potential accommodation places are fully occupied. Previous studies suggest that when the destination experiences the higher intensity of tourism development beyond its threshold, the costs associated with tourism outweigh the benefits (Dwyer and Forsyth, 1993; Mayer and Vogt, 2016). In this context, tourism at Ghorepani must be viewed from two (positive-negative) perspectives, and there is need to devise an innovative approach to mitigate the negative impacts so that tourism can be developed as a sustainable industry of this remote mountainous community. In the following paragraphs, we discuss the findings of the current study in the light of residents’ perceptions, perceived impacts and anticipated impacts. Finally, as the conclusion, we suggest the policy implications of the current findings.

4.1. Residents’ perception towards tourism

Our study reveals three different kinds of perceptions of the local residents towards tourism industry in Ghorepani. We urged the respondents to provide unbiased responses regardless of their involvement to tourism. Our results reveal that the perceptions of the local residents remain the same even if the interviewees from tourism industry speak as local residents or the local residents speak as the tourism industry entrepreneurs. Most people, regardless of their occupation, attachment with tourism, age, sex, and education, perceive only the positive benefits of tourism and show their strong willingness to further enhance tourism activities in their community. These respondents show their strong attachment towards tourism and perceives that tourism has been a boon to their community by creating multiple benefits such as provides job/service opportunity to the local unskilled people, improves the life standard of their community, provides opportunity for improved shopping, recreation, health, security, and many more. They feel that tourism is the all-in-one industry for their livelihood, and are anxious that current road expansion will severely jeopardise their livelihood. Another category of respondents also perceive tourism as an ultimate industry of this area, but they are anxious that further expansion of tourism will attract corporate industries which will ultimately not only put their small-scale investment at risk but also creates a polarized economy and divided social class not only between the local residents and the corporate industries but also among the local residents. The third category of respondents, represented by only two respondents, show their little interest in tourism expansion because of the potential negative impact that may be caused by the over accumulation of solid wastes, particularly plastics and glass bottle. However, these respondents also perceive the current benefits of tourism in their community, and do not acknowledge any imbalance between tourism development and local people’s lives in the current context. The views of local residents, though apparently different, suggest their fairly uniform attitude towards the tourism industry. Many people at Ghorepani strongly believe that the current situation of tourism is acceptable, and they are willing to increase the tourism activity in the no cost of degradation of their traditional culture, life style, language, and unique identity in the world. Our result is consistent with the findings of Easterling (2004) who suggests that the perception of local residents to tourism development is directly linked to the degree of benefits they receive from the tourism.

4.2. Perceived impacts of tourism

Our findings reveal that tourism has remarkably improved the social and economic status of the village, and thus it has been established as the most integral component not only in terms of economic and social development but also for the livelihood of the entire community. Unlike previous findings in other destinations where tourism brings several intangible costs (Greiner et al., 2004; Mayer and Vogt, 2016; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009), our result reveals that all aspects of the costs, i.e., economic, social, and environmental costs of tourism are to the minimal level and within the tolerable limits.

Our results reveal that the economy and employment opportunity of the village are entirely dependent upon tourism, i.e., tourism contributes for more than 95% of the employment opportunity and local economic activities. The tourism industry of this area is highly lucrative (entrepreneurs receive benefits up to four times higher than their actual investment, employees get very handsome salary, and local residents get very high price of their local products). The economic costs of tourism such as inflation, increased price of land and housing, job seasonality etc. which are prevalent in several other tourism destinations (Dyer et al., 2007; Greiner et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2018; Liu and Li, 2018; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009) are either not obvious or non-significant to this community. The absence of warehouse for the repair and maintenance of electrical appliances and obligation to mules-transport system due to the lack of motorable road are the major economic costs acknowledged by the local residents. These marginal economic costs have readily been compensated by the profit. Thus, Ghorepani can be regarded as a community with high economic and tourism activity. Based on the suggestion of Allen et al. (1993) that the community with higher tourism development and higher economic growth are favourable for tourism development, the further expansion of tourism in Ghorepani seems economically beneficial.

Our result reveals no significant social impacts of tourism on the community of Ghorepani. Previous studies on the social impacts of tourism suggest that destination community experiences several social costs such as degradation in traditional language, culture and skill, loss of tranquillity, increased crime rate, prostitution, impact on traditional belief and religion etc (Greiner et al., 2004; Haralambopoulos and Pizam, 1996; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009). However, none of these potential social costs are prevalent in the community, and thus our current finding is inconsistent with the previous findings (Greiner et al., 2004; Haralambopoulos and Pizam, 1996; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009).

Previous studies suggest that the impact of tourism in a community depends upon several external factors such as extent of tourism development, degree of dependency on tourism, resident’s proximity to the site, type of tourism etc., and vary among the different groups within a community (Besculides et al., 2002; Haralambopoulos and Pizam, 1996; Mason and Cheyne, 2000). Generally, residents who are directly involved in tourism see the tourism beneficial and the rest of the residents perceive tourism negatively (Besculides et al., 2002; Haralambopoulos and Pizam, 1996). However, our result suggests that the impacts of tourisms at Ghorepani are neither affected by those external factors nor varied among different groups within the community. We found that all the local residents, regardless of their involvement in tourism occupation, perceive the higher benefits of tourism than the costs. As tourism generates a very high level of economic and social benefits with no any obvious negative impacts, tourism has been serving as the key industry of the village. Thus, decline in tourism activity not only affects the economic and social development of the village but also causes severe devastation in the livelihood of the local residents.

4.3. Anticipated impacts of tourism

Although tourism has been the backbone of social and economic development of the community, there are some important anticipated issues that need to be resolved to maintain the sustainability of tourism at Ghorepani. Currently, the local government in collaboration with the provincial government is constructing a motorable road with the aim of connecting Ghorepani to Pokhara in the east and Beni/Jomsom in the west. Ghorepani is very fragile not only topographically but also from the ecosystem point of view. As a part of Annapurna Conservation Area, this site harbours many invaluable flora and fauna that are confined only to this area including the world’s largest Rhododendron Forest (personal communication, Dr. Babu Ram Paudel, an environment and biodiversity expert). Thus, construction of road would not only induce calamities such as landslide, flood, deforestation etc. but also would jeopardise the valuable biodiversity and ecosystem (Aragon, 2018; Romero, 2016). Moreover, the construction of road would diminish the trekking activity as visitors would prefer vehicular transport. Thus, the identity of the site as a popular trekking destination would be lost, which would ultimately reduce the tourism activity of this area. This is a serious anxiety expressed by all the respondents during our assessment survey. As residents' perception and attitude towards the infrastructure development is crucial to enhancing the sustainability of tourism destinations (Chan and Bhatta, 2013; Moscardo, 2015; Saarinen, 2019), preserving the traditional trekking routes and valuable biodiversity and ecosystem is an utmost need, not only from the perspective of tourism but also from the environmental context. Another potential impact of current road expansion is that it may attract big corporate houses. Thus, Ghorepani might be changing towards the high-end tourism industry which may drastically change the long-standing identity of the village, and jeopardise the livelihood of the local residents. This finding is consistent with the several previous findings (Haralambopoulos and Pizam, 1996; Mason and Cheyne, 2000; Ryan and Montgomery, 1994; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009). Considering these negative impacts of rural road expansion on the tourism industry of Ghorepani, it is imperative that there is the need of a sensitive approach while expanding rural road in this trekking region. We, based on our own assessment and the view of biodiversity expert (Pers. comm. BRP) suggest that the road should be constructed in an alternative track which neither overlaps with the trekking routes nor passes through the Rhododendron forest. It is also imperative that to ensure the sustainable tourism in Ghorepani, the rural road expansion should not replace the long-established trekking tourism.

In the current context, the environmental impact of tourism at Ghorepani are not obvious, and thus there are no any site-specific efforts in conserving the environment of Ghorepani. Some respondents, however, express their serious concern about the indiscriminate disposing of garbage by the visitors which not only deteriorates the natural beauty of the landscape but also may induce forest fire. Although the visitors of Ghorepani have to follow the regulations of conservation area pertaining to local environment, and thus they are not allowed to randomly dispose garbage, due to lack of monitoring bodies along the trails, visitors dispose the garbage elsewhere as they wish. Therefore, there is a need of establishment of check posts along the trekking route. Moreover, although the garbage along the walking trails and from the observation site is regularly collected and managed accordingly, the current practice of waste management particularly non-degradable waste management is unsustainable. Currently, the degradable wastes are spread to the floor of forest as manure while the non-degradable solid wastes are either burnt or buried under the ground. Although the current practice of non-degradable wastes disposal seems inappropriate, given the remoteness of the study site, there are no better alternatives of waste disposal at the moment.

Some respondents express their concern about the unreliability of power supply (electricity) and internet services which when interrupted by any means takes even a week to resume. Loss of tranquillity, potentiality of loss of local language and culture, overexploitation of cultivable land for tourism activity, deterioration in community cohesiveness/local patriotism, possible social and economic polarization of society are the other remarkable concerns of the local residents. As the anxiety of local residents over the tourism development/expansion is more critical than the current consequences (Hernandez et al., 1996), the stakeholders are required to give a solemn thought in addressing the current and anticipated anxiety of the local residents before expanding tourism and its allied activities to this community. If these issues are properly addressed, tourism would be established as a sustainable industry in Ghorepani and serves the community as the backbone of the economy.

4.4. Future direction of tourism development

Our results reveal that the tourism industry of Ghorepani at its current form is a highly lucrative industry with no remarkable social, economic, and environmental costs. Thus, it reveals that Ghorepani has not yet reached the threshold point that locals and their space are overwhelmed by tourists, and thus the village is coveting the further promotion of tourism industry. Considering the current policy of local/provincial government and the motives of a few entrepreneurs, it is likely that tourism promotion in Ghorepani takes the directionality of increasing the pace of touristic activities via expansion of motorable road and other infrastructures. If tourism promotion in Ghorepani occurs in this direction, due to improved transportation service, it will not only attract more tourists but also induces for other developmental changes (Chan and Bhatta, 2021), and thus the tourism industry will be able to generate high economic activity by providing more jobs/service/trade opportunity. However, this directionality of tourism development will attract big corporate houses which not only transform Ghorepani towards the high-end tourism destination but also could impose several costs to the destination community which will eventually jeopardize the traditional skills, culture, identity, and most importantly the livelihood of the local residents. If motorable roads are built and the facility of public transportation improved, the trekking-based tourism activity would diminish drastically, and in the due course the unique identity of this destination as one of the safest trekking routes in the world would be lost. Our assessment reveals that local residents/most entrepreneurs are not willing to increase the pace of tourism development via expansion of motorable road and other infrastructures. As the anxiety of the local residents is more important than the actual consequences of tourism (Hernandez et al., 1996), stakeholder must be very cautious while deciding the directionality of tourism development. Based on our current findings, and the findings and recommendations of several previous studies which suggest that infrastructure development causes significant impact on the local communities and the environment (Hernandez et al., 1996; Nepal, 2016; Nyaupane et al., 2018; Tsundoda and Mendlinger, 2009), as well as considering the worrying voice of local residents, we suggest that tourism promotion in Ghorepani should occur without major infrastructure development, particularly without motorable road expansion. If Ghorepani decides to expand tourism without major infrastructure development, it would not generate the economic activity to its optimum potentiality, but ensures the balance between tourism development and local people’s lives, conservation of its unique traditional identity, preservation of local landscape, ecosystem and biodiversity. Moreover, this approach mitigates the potential negative impacts of tourism in Ghorepani. Thus, tourism will be established as the sustainable industry of this area, which in the due course would play a key role to enhance the economy of the community and to resolve the growing unemployment problem. However, adopting this directionality of tourism may suffer from several obstacles and thus communities, concerned organizations such as ACAP, and all the stakeholders should show strong determinations towards their goals. Had this approach been successful, it would serve as a key model to promote and mange tourism in other similar mountainous destinations.

4.5. Potential approaches for impact management

Our study indicates a few negative impacts of tourism at Ghorepani that are being overlooked by the local residents and stakeholders. This implies that there is no supervision towards the visitors' quantity and visitors’ activities, i.e., tourism at Ghorepani is being promoted without assessment. This caveat highlights the need to develop appropriate management plans focusing towards the long-term sustainability of tourism at Ghorepani. In the current context, with reference to the tourism management in other destinations, two approaches have been widely used to assess and mitigate the negative impacts of tourism: Tourism Carrying Capacity (TCC) and Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) (Bentz et al., 2016; Bera et al., 2015). Currently, a new approach known as Tourism Impact Assessment (TIA) has been developed by Canteiro et al. (2018) which particularly focuses on the assessment of environmental impact of tourism. The central theme of TCC is to create a limit on tourist number at a destination in accordance with the priorities of the stakeholders in such a way that the touristic activity should not destroy the physical, economic and socio-cultural environment (Coccossis and Mexa, 2017). Considering the current trend of tourist arrival in Ghorepani (the arrival of tourist at Ghorepani fluctuates significantly among the different seasons), it is hard to determine the number of tourists that could visit Ghorepani at a certain time and under certain conditions, i.e., as the environmental and social conditions of Ghorepani change temporarily, it is almost impractical to determine the number of visitors in accordance with the temporal changes. Thus, TCC seems impractical to implement as this approach is not flexible with temporal changes. The second approach LAC tends to establish a threshold limit of the acceptable changes under the environmental setting of the destinations. Although this approach seems rather practical than TCC, determining whether the extent of changes is acceptable or not is a challenging task as it not only requires the expert consultation but also may suffer from data deficiency such as lack of sufficient biophysical indicators, limited understanding of environmental, cultural, social and economic variability etc (Bentz et al., 2016; SEWPAC, 2012). The third approach, TIA, seems relatively practical to evaluate the magnitude of impact since it not only entails proper identification of pressure and impact components but also develops well-defined criteria to estimate the impact magnitude. Based on the magnitude of impact, the extent of changes can be easily determined as acceptable or unacceptable. Moreover, application of TIA in identification of pressure and impact component and evaluation of impact magnitude does not require an expert (Canteiro et al., 2018). However, TIA alone seems insufficient as this approach is primarily useful in evaluating the magnitude of the impact. Based on our current findings, geographical and other complexities associated with the study sites, and merits/demerits of LAC and TIA, we suggest the integrated application of TIA and LAC would be a meaningful approach to achieve the goal of sustainable tourism. When these two approaches are used in an integrated way, it not only enables to assess and control the growth of touristic activities but also mitigates the increasing magnitude of negative impacts.

5. Conclusions

We conclude that the tourism industry of Ghorepani has not yet reached the threshold point that locals and their space are overwhelmed by tourists. However, considering the current global pace of tourism expansion in protected area, Ghorepani is also likely to experience the high pressure of tourism expansion in the forthcoming years. Therefore, in the near future, the expansion/diversification of tourism industry of Ghorepani is inevitable. If the current trend of tourism promotion, i.e., promotion without assessment continues, the further tourism development in Ghorepani is likely to proceed in the directionality of increasing the pace of touristic activities via expansion of roads and other infrastructure. However, considering the nature and culture based tourism product of the destination, conservation of biodiversity, ecosystem, landscape, traditional culture, and long established trekking activity is of utmost need. Therefore, to ensure that tourism industry of Ghorepani does not adversely affect on these areas, tourism promotion should occur without major infrastructure development. Moreover, to achieve the long term sustainability of tourism industry and to ensure the conservation of ecosystem and landscape, touristic activities should be properly monitored, assessed and managed regularly (Das and Chatterjee, 2015). We suggest that integrated use of TIA and LAC would be effective in monitoring and managing the magnitude of impacts the tourism industry generates on the community, economy and environment of Ghorepani.

Overall, this study assessed the economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits of tourism in a remote mountainous village located within a conservation area. The central message of our current findings is that tourism in Ghorepani is highly lucrative and thus coveting the further promotion. We reiterate that to ensure the long-term sustainability of the industry as well as to ensure the conservation of ecosystem, traditional culture, and long established trekking tourism, further promotion of tourism at this destination should occur without major infrastructure development. Moreover, regular assessment and management of the potential negative impacts associated with the touristic activities by the integrated use of TIA and LAC would enable to achieve the goal of ecosystem conservation and long term sustainability of tourism industry of this mountainous village.

Our current findings have following major implications. Considering the rarity of comprehensive studies in Nepalese tourism, this study would be valuable towards expanding the limited literature on the impact of tourism in the Nepalese context. Because knowledge on the impacts of tourism on local communities forms the key element in formulating strategies for long term sustainable tourism (Diedrich and García-Buades, 2009), the findings of this study provide valuable insights to develop appropriate management plans/policies for the establishment, expansion, and diversification of nature and culture based tourism industry across the mountainous destinations with long-term sustainability goals. Moreover, the findings of this study suggest that tourism in Ghorepani is a highly lucrative industry. This finding has broader implication beyond the case study and suggests that establishment of tourism industry in the various mountainous destinations across the Nepalese Himalayas could enhance the economic and social status of the country as well as alleviate the unemployment problem of the country. Thus, this finding provides evidence to support that tourism is the integral part of Nepalese economy. In addition, the findings of this study provide baseline knowledge in managing tourism in conservation area.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Rekha Baral: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Deepak Prasad Rijal: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

All the data will be made available upon the acceptance of manuscript.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary content related to this article has been published online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10395.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the local residents and the stakeholders of tourism industry of Ghorepani for their cordial cooperation and support during our assessment period. We thank Dr. Baburam Paudel, Dr. Subodh Adhikari, and Dr. Mani Shrestha for providing expert opinion. We thank Mr. Brihaspati Poudel and Dipendra Lamichhane for assisting in the field data collection.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Allen L.R., Hafer H.R., Long P.T., Perdue R.P. Rural residents’ attitudes toward recreation and tourism development. J. Trav. Res. 1993;21:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Allen L.R., Long P.T., Perdue R.R., Kieselbach S. The impact of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. J. Trav. Res. 1988;27:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-García F., Balbuena Vázquez A., Cortés Macías R. Resident’s attitudes towards the impacts of tourism. Tourism Manag. Perspect. 2015;13:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-García F., Cortés-Macías R., Parzych K. Tourism impacts , tourism-phobia and gentrification in historic centers:the cases of málaga(Spain) and gdansk (Poland) Sustainability. 2021;13:408. [Google Scholar]

- Aragon R. National Agrarian University La Molina; Lima, Peru: 2018. Perceptions of Sustainable Tourism Management: Comparative Study in Two Communities Adjacent to National Reserves (Tambopata and Titicaca), Peru. [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer J., Cantavella-Jordá M. Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: the Spanish case. Appl. Econ. 2002;34(7):877–884. [Google Scholar]

- Balmford A., Beresford J., Green J., Naidoo R., Walpole M., Manica A. A global perspective on trends in nature-based tourism. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(6):1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral N. Assessing the temporal stability of the ecotourism evaluation scale: testing the role and value of replication studies as a reliable management tool. J. Sustain. Tourism. 2015;23(2):280–293. [Google Scholar]

- Baral N., Stern M.J., Hammett A.L. Developing a scale for evaluating ecotourism by visitors: a study in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. J. Sustain. Tourism. 2012;20(7):975–989. [Google Scholar]

- Bentz J., Lopes F., Calado H., Dearden P. Sustaining marine wildlife tourism through linking “limits of acceptable change” and zoning in the wildlife tourism model. Mar. Pol. 2016;68:100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bera S., Das Majumdar D., Paul A.K. Estimation of tourism carrying capacity for Neil Island. J. Coast. Sci. 2015;2(2):46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Besculides A., Lee M., McCormick P.J. Residents’ perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Ann. Tourism Res. 2002;29:303–319. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari L.R. The role of tourism for employment generation in Nepal. Nepal J. Multidiscipl. Res. 2019;2(4):17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley R. In: Case Studies in Ecotourism. Buckley R., editor. CABI; Oxford. UK: 2003. Annapurna conservation area project, Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Burger V. Cornell University; 1978. The economic impact of tourism in Nepal, an input output analysis. Unpubli, a Dissertation of Doctor of Philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- Butler R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980;24:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Canteiro M., Córdova-Tapia F., Brazeiro A. Tourism impact assessment: a tool to evaluate the environmental impacts of touristic activities in natural protected areas. Tourism Manag. Perspect. 2018;28:220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Chan R., Bhatta K. Ecotourism planning and sustainable community development: theoretical perspectives for Nepal. S. Asian J. Tourism Herit. 2013;6(1):69–96. http://sajth.com/old/jan2013/Microsoft Word - 006 Roger Chan_Final 2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chan R.C.K., Bhatta K.D. Trans-Himalayan connectivity and sustainable tourism development in Nepal: a study of community perceptions of tourism impacts along the Nepal–China Friendship Highway. Asian Geogr. 2021:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Coccossis H., Mexa H. Routledge; 2017. The Challenge of Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Comerio N., Strozzi F. Tourism and its economic impact: a literature review using bibliometric tools. Tourism Econ. 2019;25(1):109–131. [Google Scholar]

- Das M., Chatterjee B. vol. 14. 2015. Ecotourism: a panacea or a predicament? (Tourism Management Perspectives). [Google Scholar]

- Deguignet M., Juffe-Bignoli D., Harrison J., Macsharry B., Burgess N., Kingston N. UNEP-WCMC; Cambridge, UK: 2014. United Nation’s List of Protected Areas.http://www.unep-wcmc.org/posters/ScientificSeries/sowpa/pdfs/lowres/regional2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich A., García-Buades E. Local perceptions of tourism as indicators of destination decline. Tourism Manag. 2009;30:512–521. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer L., Forsyth P. Assessing the benefits and costs of inbound tourism. Ann. Tourism Res. 1993:751–768. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer P., Gursoy D., Sharma B., Carter J. Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tourism Manag. 2007;28(2):409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Easterling D.S. The resident’s perspective in tourism research. J. Trav. Tourism Market. 2004;17:45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Nepal(GON) Tourism Policy 2065. Ministry of Tourism and Civil; Aviation, Kathmandu, Nepal: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner R., Mayocchi C., Larson S., Stoeckl N., Schweigert R. 2004. Benefits and Costs of Tourism for Remote Communities: Case Study for the Carpentaria Shine in North-west Queensland.http://www.landmanager.org.au/downloads/Carpentaria Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gurung H. 1991. Environmental Management of Mountain Tourism in Nepal. Bangkok: ST/ESCAP/959. [Google Scholar]

- Haralambopoulos N., Pizam A. Perceived impacts of tourism: the case of Samos. Ann. Tourism Res. 1996;23(3):503–526. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez S.A., Cohen J., Garcia H.L. Residents’ attitudes towards an instant resort enclave. Ann. Tourism Res. 1996;23:755–779. [Google Scholar]

- Josimovic B., Petric J., Milijic S. The use of the Leopold Matrix in carrying out the EIA for wind farms in Serbia. Energy Environ. Res. 2014;4(1):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Karki D. The dynamic relationship between tourism and economy: evidence from Nepal. J. Bus. Manag. 2018;V(I):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kisi N. A strategic approach to sustainable tourism development using the A’WOT Hybrid Method: a case study of Zonguldak, Turkey. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2019;11(4) [Google Scholar]

- Ko D.W., Stewart W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Manag. 2002;23(5):521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhokulov S., Chen X., Yang D., Issanova G., Samarkhanov K., Aliyeva S. Assessment of tourism impact on the socio-economic spheres of the Issyk-Kul Region (Kyrgyzstan) Sustainability (Switzerland) 2019;11(14):3886. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J., Hussain K. A Review of assessing the economic impact of business tourism: issues and Approaches. Int. J. Hospit. Tourism Sys. 2014;7(2):49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.H., Chen H.S., Liou G.B., Tsai B.K., Hsieh C.M. Evaluating international tourists’ perceptions on cultural distance and recreation demand. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2018;10(12):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold L., Clarke F., Hanshaw B., Balsley J. vol. 2. 1971. Procedure for Evaluating Environmental Impact. US Geological Survey Circular. [Google Scholar]

- Lepp A. Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tourism Manag. 2007;28(3):876–885. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. (Rose), Li J. (Justin) Host perceptions of tourism impact and stage of destination development in a developing country. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2018;10(7):2300. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Oré E.M., Custodio M. Visitor environmental impact on protected natural areas: an evaluation of the Huaytapallana regional conservation area in Peru. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tourism. 2020;31 [Google Scholar]

- Mason P., Cheyne J. Residents’ attitudes to proposed tourism development. Ann. Tourism Res. 2000;27(2):391–411. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson A., Wall G. Longman; Harlow, UK: 1982. Tourism: Economic, Physical and Social Impacts. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M., Vogt L. Economic effects of tourism and its influencing factors. Z. Tourismuswissenschaft. 2016;8(2):169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdowall S., Choi Y. A comparative analysis of Thailand residents’ perception of tourism’s impacts. J. Qual. Assur. Hospit. Tourism. 2010;11(1):36–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mckercher B. 2003. Sustainable Tourism Development– Guiding Principles for Planning and Management. A Presentation to the National Seminar on Sustainable Tourism Development. Bishkek, Kyrjistan, November 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mikayilov J.I., Mukhtarov S., Mammadov J., Azizov M. Re-evaluating the environmental impacts of tourism: does EKC exist? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2019;26:19389–19402. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05269-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo G. CABI Publications; Wallingford, UK: 2015. Building Community Capacity for Tourism Development. [Google Scholar]

- MoTCA . Ministry of Tourism and Civil Aviation, Government of Nepal; Kathmandu: 2008. Tourism Policy 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MoTCA . 2019. Nepal Tourism Statistics 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal S. Tourism in protected areas: the Nepalese Himalaya. Ann. Tourism Res. 2000;27(3):661–681. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal S.K., Kohler T., Banzhaf B.R. Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research; Zürich, Switzerland: 2002. Great Himalaya: Tourism and the Dynamics of Change in Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal Sanjay K. In: A Review of the Encyclopedia of Sustainable Tourism. Cater C., Garrod B., Low T., editors. CABI; Wallingford: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- NPC . National planning Commission; Kathmandu: 2010. Approach Paper to the Three Year Plan (2067/68- 2069/70) (in Nepali) [Google Scholar]

- NTB . Nepal Tourism Board; Kathmandu: 2003. Nepal Guidebook. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo R., Gursoy D. Residents support for tourism: an identity perspective. Ann. Tourism Res. 2012;39(1):243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane G.P., Lew A.A., Tatsugawa K. Perceptions of trekking tourism and social and environmental change in Nepal’s Himalayas. Tourism Geogr. 2014;16(3):415–437. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane G.P., Poudel S., Timothy D.J. Assessing the sustainability of tourism systems: a social-ecological approach. Tourism Rev. Int. 2018;22:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R.N., Chettri P., Kunwar R.R., Ghimire G. Case study on the effects of tourism on culture and the environment: Nepal - Chitwan-Sauraha and Pokhara-Ghandruk. RACAP Ser. Cult. Tourism Asia. 1995;4:66. [Google Scholar]

- Paudyal S. Does tourism really matter for economic growth? evidence from Nepal. Nepal Rastra Bank Econ. Rev. 2012;24(1):48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, Rossi S.D., Hernando A., Barros A. Current knowledge and future research directions for the monitoring and management of visitors in recreational and protected areas. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tourism. 2018;21:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- PTC Destination around the Pokhara. Pokhara Tourism Mirror. 2008;1(2) Pokhara Tourism council, Pokhara, Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Ridderstaat J., Croes R., Nijkamp P. 2013. Modelling tourism development and long- run economic growth in Aruba; pp. 1–22. (Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper, 145). [Google Scholar]

- Riveros S., Blanco M. 2003. El agroturismo, una alternativa para revalorizar la agroindustria rural como mecanismo de desarrollo local. Lima (Perú): IICA (PRODAR) [Google Scholar]

- Romero J. Tourism activity and its impact on the Lomas ecosystem in the Lachay national Reserve. Big Bang Faustiniano. 2016;5(4):30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C., Montgomery D. The attitudes of Bakewell residents to tourism and issues in community responsive tourism. Tourism Manag. 1994;15(5):358–369. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen J. In: A Research Agenda for Sustainable Tourism. McCool S.F., Bosak K., editors. Edward Elgar Publishing; Cheltenham, UK: 2019. Communities and sustainable tourism development: community impacts and local benefit creation tourism; pp. 206–223. [Google Scholar]

- Satyal Y.R. Nath Publishing House; Varanasi, India: 1988. Tourism in Nepal:A Proile. [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira T.N., Nunes P.M. Does tourism influence economic growth? a dynamic panel data approach. Appl. Econ. 2008;40(18) [Google Scholar]

- SEWPAC . Australian Government; 2012. Limits of Acceptable Change – Fact Sheet. Department of Sustainable, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Shih W., Do N.T.H. Impact of tourism on long-run economic growth of Vietnam. Mod. Econ. 2016;7(3):371–376. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha H.P., Shrestha P. Tourism in Nepal: a historical perspective and present trend of development. Himal. J. Sociol. Antropol., V. 2012:54–75. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens S. Tourism and deforestation in the Mt Everest region of Nepal. Geogr. J. 2003;169(3):255–277. [Google Scholar]