Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Choosing from multiple kidney failure treatment modalities can create decisional conflict, but little is known about this experience before decision implementation. We explored decisional conflict about treatment for kidney failure and its associated patient characteristics in the context of advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Study Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting & Participants

Adults (N = 427) who had advanced CKD, received nephrology care in Pennsylvania-based clinics, and had no history of dialysis or transplantation.

Predictors

Participants’ sociodemographic, physical health, nephrology care/knowledge, and psychosocial characteristics.

Outcomes

Participants’ results on the Sure of myself; Understand information; Risk-benefit ratio; Encouragement (SURE) screening test for decisional conflict (no decisional conflict vs decisional conflict).

Analytical Approach

We used multivariable logistic regression to quantify associations between aforementioned participant characteristics and decisional conflict. We repeated analyses among a subgroup of participants at highest risk of kidney failure within 2 years.

Results

Most (76%) participants reported treatment-related decisional conflict. Participant characteristics associated with lower odds of decisional conflict included complete satisfaction with patient–kidney team treatment discussions (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.03-0.88; P = 0.04), attendance of treatment education classes (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.16-0.90; P = 0.03), and greater treatment-related decision self-efficacy (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99; P < 0.01). Sensitivity analyses showed a similarly high prevalence of decisional conflict (73%) and again demonstrated associations of class attendance (OR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.07-0.96; P = 0.04) and decision self-efficacy (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91-0.99; P = 0.03) with decisional conflict.

Limitations

Single-health system study.

Conclusions

Decisional conflict was highly prevalent regardless of CKD progression risk. Findings suggest efforts to reduce decisional conflict should focus on minimizing the mismatch between clinical practice guidelines and patient-reported engagement in treatment preparation, facilitating patient–kidney team treatment discussions, and developing treatment education programs and decision support interventions that incorporate decision self-efficacy–enhancing strategies.

Index Words: Chronic kidney disease, decisional conflict, dialysis, transplant, treatment decision-making

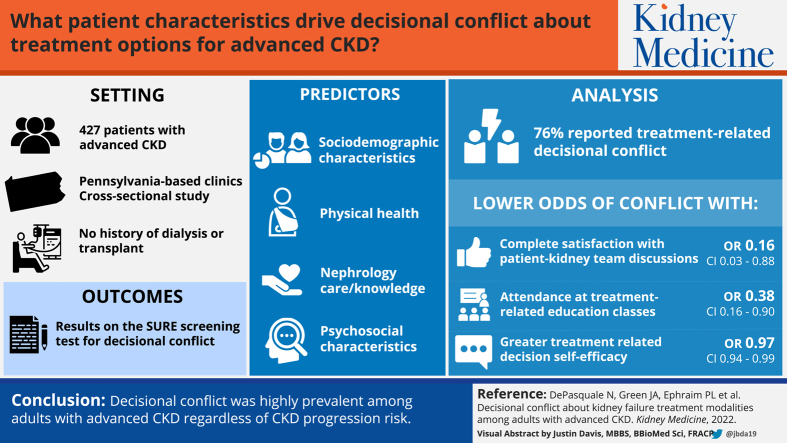

Visual Abstract

Plain-Language Summary.

Adults approaching kidney failure face a difficult treatment decision-making process that can create decisional conflict. We explored decisional conflict and its relation to patient characteristics among 427 adults with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) and a subset of 171 adults at greatest risk of kidney failure within 2 years. Decisional conflict was highly prevalent regardless of CKD progression risk. Across samples, participants who attended treatment education classes and reported greater decision self-efficacy had less odds of decisional conflict. Completely satisfactory patient–kidney team treatment discussions were associated with lower odds of decisional conflict in the full sample. Efforts to reduce decisional conflict should focus on timely treatment education, person-centered treatment discussions, and incorporation of decision self-efficacy–enhancing strategies into decision support mechanisms.

Adults progressing from earlier stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) to kidney failure face a particularly complex treatment decision-making process.1 Kidney failure treatment options include multiple dialysis modalities, 2 transplantation types, and conservative medical therapy.1 Each option has different advantages, drawbacks, and implications regarding patient survival, morbidity, cost, quality of life, well-being, cognitive function, and daily routines.2, 3, 4 Still, many adults with CKD lack adequate information to make informed treatment decisions, and available patient education does not consistently adhere to best practices.5 Other factors further complicating this decision-making process include managing opinions from several parties, considering treatment effects on caregivers, accounting for the role of multifaceted organizational and socioeconomic structures, and contemplating one’s own needs, values, and preferences.6, 7, 8, 9 In light of these circumstances, choosing a kidney failure treatment may create a decision-making context ripe for decisional conflict.

Decisional conflict is a state of uncertainty about choosing the best course of action from competing options that neither entirely satisfy personal values nor are wholly free from undesirable outcomes.10,11 These options typically offer different pros and cons, involve value tradeoffs, and induce anticipated regret over rejected options.11,12 Although choosing a kidney failure treatment can be characterized similarly, decisional conflict remains poorly understood among adults with advanced CKD.13, 14, 15, 16 Yet, decisional conflict may result in decisions misaligned with values or preferences; adverse changes in behavior, psychological well-being, and health; and decreased CKD-related treatment satisfaction and patient activation.14,15,17 Further, unresolved decisional conflict can lead to undesirable post-decision consequences, including lower treatment adherence and decisional distress.15,17,18

The primary purpose of the present study was to explore decisional conflict and identify associated sociodemographic, physical health, nephrology care/knowledge, and psychosocial patient characteristics among adults with advanced CKD who had not implemented a kidney failure treatment decision. The secondary purpose was to focus on a subset of participants with the greatest risk of progressing to kidney failure within 2 years (ie, highest-risk participants). We expected decisional conflict to be less prevalent among highest-risk participants given their recommendation for treatment preparation in clinical practice guidelines. By elucidating associations between nonmodifiable patient characteristics (eg, age) and decisional conflict, this study may facilitate identification of adults with advanced CKD who need or would benefit from additional support during the treatment decision-making process. Likewise, identifying associated modifiable patient characteristics (eg, CKD knowledge) may inform targeted intervention efforts to reduce decisional conflict and its downstream effects.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis using baseline data from the PREPARE NOW study,19 a cluster randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02722382) evaluating the effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve kidney failure treatment preparation. The trial occurred within 8 Geisinger Health System nephrology practices providing outpatient care to approximately 4,000 adults. Eligible participants were English-speaking, aged 18 years or older, seen by a nephrologist at a Geisinger Health System study site within the previous year, had advanced CKD or a “very high-risk prognosis” in accordance with Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria (ie, stages G3aA3, G3bA2-A3, G4A1-A3, and G5A1-A3 based on estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] and albuminuria),20 and had not started dialysis. Participants verbally consented to use of their electronic health record (EHR) and completion of a pre-intervention questionnaire administered by trained research staff between May 2017 and February 2018. The questionnaire was offered in a short or long format; decisional conflict was measured in the long format. The present analysis focuses on participants with no history of dialysis or transplantation at the time of questionnaire completion and complete decisional conflict data. All study protocols were approved by Geisinger Health System and Duke University through a single institutional review board (IRB approval number Pro00075488).

Decisional Conflict

We measured decisional conflict about kidney failure treatment modalities with the Sure of myself; Understand information; Risk-benefit ratio; Encouragement (SURE) screening test.21,22 SURE is the only version of the Decisional Conflict Scale developed for use in clinical practice.12,23 Because administration time for the Decisional Conflict Scale discourages use in the clinical setting, SURE is streamlined to help providers identify patients with clinically significant decisional conflict as quickly as possible.21 SURE has psychometrically adequate properties, correlates with the Decisional Conflict Scale in the expected direction, and discriminates between people who make or delay decisions.17,21

Consistent with the Decisional Conflict Scale, SURE is preceded with an unscored option preference question. Participants are asked to hypothetically choose a kidney failure treatment, with options including home hemodialysis, in-center hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, kidney transplant, medical management only, or “unsure.” The SURE test comprises 4 items reflecting core concepts of the Ottawa Decision Framework considered relevant for all decisional stages: feeling certain, informed, clear about values, and supported in decision-making.24 For each item, a response of “yes” scores 1 (no decisional conflict) and a response of “no” or “don’t know” scores 0 (decisional conflict). Responses are summed, with total scores ranging from 0 to 4. A perfect score of 4 indicates no decisional conflict, whereas a score of <3 reflects decisional conflict and is meant to prompt providers to help patients make decisions or refer them to appropriate resources.21

Participant Characteristics

We obtained information about sociodemographic, physical health, nephrology care/knowledge, and psychosocial characteristics via questionnaire and EHR data. We considered these characteristics to be potentially relevant to decisional conflict based on their theoretical or empirical association in past studies.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,25,26

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Participants reported their age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White vs other), marital status (married/living with partner vs not married/living with partner), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate/general equivalency diploma, some college, and college graduate or more), employment status (employed/looking for work, unemployed, retired, or retired because of disability), and annual household income (<$30,000, $30,000-$59,000, and ≥$60,000). We used EHR data to assess health insurance status (commercial, government/other, Medicaid, and Medicare). We measured subjective health literacy with the Brief Health Literacy Screen.27,28 A score of <9 translates to inadequate/marginal health literacy (range: 3-15).

Physical Health Characteristics

We examined physical health characteristics via EHR data. We measured comorbidity burden with the Charlson comorbidity index.29 The index score is the sum of weighted values assigned to 19 conditions, with higher scores indicating greater burden (range: 0-37). Before survey completion, we obtained the most recent laboratory value for 3 indicators of kidney function: eGFR (based on the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation),30 Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE) score (<10%, not high-risk vs >10%, high-risk of kidney failure within 2 years),31,32 and albumin-creatinine ratio (>30 mg/g, at risk of glomerular filtration rate decline).33

Nephrology Care/Knowledge Characteristics

We estimated duration of nephrology care by referencing EHR data for the date of participants’ first nephrology visit. Participants assessed the patient-centeredness of their last nephrology visit with questions adapted from the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness Scale.34,35 Higher scores correspond to more patient-centeredness (range: 1-4). Participants who reported prior treatment discussions with their kidney team rated discussion satisfaction on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 3 = completely satisfied. Participants answered yes/no to, “Has your kidney doctor recommended a specific treatment option if your kidneys were to stop working?” and “Have you ever attended a class to learn more about hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or kidney transplant?” We assessed disease knowledge with questions from the Kidney Knowledge Survey.36 Total scores signify the sum of correct responses, with higher scores translating to more knowledge (range: 0-8).

Psychosocial Characteristics

The Patient Health Questionnaire assessed the frequency of depressive symptomatology in the past 2 weeks (0 = not at all, 3 = nearly every day).37 Total scores of >10 demonstrate “at least moderate depressive symptoms” and <10 demonstrate “mild or no depressive symptoms.” An adapted version of the Decision Self-Efficacy Scale measured confidence to make an informed choice about kidney failure treatment.38 Total scores range from 0 (not confident) to 100 (extremely confident). The Perceived Kidney/Dialysis Self-Management Scale assessed participants’ beliefs about how well they manage their own kidney care.39 Higher scores reflect greater self-management self-efficacy (range: 8-40). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Short Form v2.0 4a scales examined perceived receipt of informational, emotional, and instrumental support.40, 41, 42 Responses are scored on a T-score metric (population mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10), with higher values suggesting more support.

Statistical Analysis

We described participant characteristics overall and according to SURE scores. We assessed differences in the sociodemographic, physical health, nephrology care/knowledge, and psychosocial characteristics of participants with and without decisional conflict by using Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. We performed logistic regression to estimate unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between each individual characteristic and decisional conflict. We then constructed 1 multivariable logistic regression model accounting for all characteristics to estimate adjusted ORs and 95% CIs. Additionally, we assessed whether the pattern of results changed when repeating analyses with a subset of highest-risk participants or those at greatest risk of 2-year progression to kidney failure (ie, eGFR <30 or KFRE score of >10% at baseline).31,32 Highest-risk participants are targeted in current KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for: (1) timely referral for treatment planning and preparation; and (2) receipt of information and education about transplantation.31,32 All hypothesis tests were 2-sided and performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Participant Characteristics

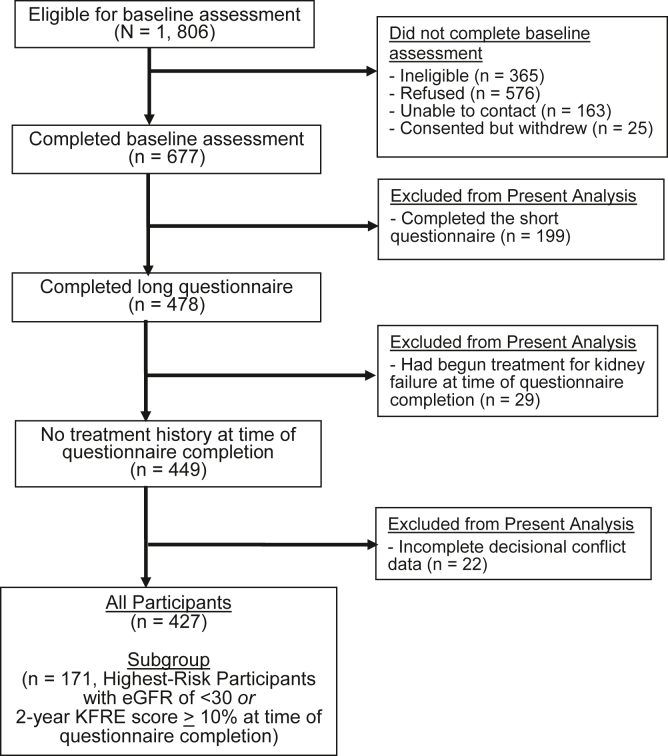

A total of 427 individuals comprised the analytic sample (Fig 1). Participants had a mean (standard deviation) age of 71.6 years (12.3 years). More than half were women (60%), non-Hispanic White (97%), married/living with a partner (55%), retired (66%), and Medicare recipients (70%). Two-thirds reported high school as their highest level of educational attainment, 32% reported an annual household income <$30,000, and 67% demonstrated adequate health literacy. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) Charlson comorbidity index score of 5.0 (3.0-7.0) reflected lower comorbidity burden. Most participants (62%) had an eGFR >30 mL/min/1.73 m2, consistent with CKD stages 2, 3a, or 3b. Sixteen percent had a high-risk KFRE score, and the median (IQR) albumin-creatinine ratio of 97.9 (51.2-277.2) suggested glomerular filtration rate decline.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram representing the inclusion of participants in the analytic samples. Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; KFRE, Kidney Failure Risk Equation. Notes: Decisional conflict was only included in the long questionnaire.

The median (IQR) duration of nephrology care was 3.8 years (1.9-6.5 years). On average, participants favorably rated the patient-centeredness of their most recent nephrology visit (mean [standard deviation] 3.6 [0.5]). Fourteen percent reported receiving a treatment recommendation from their nephrologist. Among those who had patient–kidney team treatment discussions, 19% rated them as completely satisfactory. The median (IQR) Kidney Knowledge Survey score of 5.0 (4.0-6.0) suggested moderate knowledge of CKD. The majority (91%) had not attended kidney failure treatment modality education classes (hereafter referred to as treatment education classes) and 80% reported mild or no depressive symptoms. Median (IQR) decision self-efficacy and kidney self-management self-efficacy scores of 90.9 (77.3-100.0) and 30.0 (26.0-5.0), respectively, signified higher levels of self-efficacy. Median (IQR) informational, emotional, and instrumental support scores of 57.7 (47.6-65.6), 62.0 (48.8-62.0), and 63.3 (50.7-63.3), respectively, translated to higher levels of support (Table 1). Participants who were non-Hispanic White, college graduates, retired or retired because of disability, and had a higher annual household income were more likely to be included in the study (Table S1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics Overall and According to SURE Screening Test Results for Decisional Conflict About Kidney Failure Treatment Modalities

|

Characteristic |

Response | Total N = 427 |

Decisional Conflict n = 324 (76%) | No Decisional Conflict n = 103 (24%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Age | Mean (SD) | 71.6 (12.3) | 72.6 (11.8) | 68.6 (13.2) | 0.01 |

| Sex | Female | 254 (60%) | 193 (60%) | 61 (59%) | 0.95 |

| Race | Non-Hispanic White | 412 (97%) | 314 (97%) | 98 (95%) | 0.35 |

| Marital status | Married/living with partner | 235 (55%) | 183 (57%) | 52 (50%) | 0.47 |

| Not married/living with partner | 191 (45%) | 140 (43%) | 51 (50%) | ||

| Education | Less than high school | 58 (14%) | 46 (14%) | 12 (12%) | 0.84 |

| High school graduate/GED/some college | 283 (66%) | 211 (65%) | 72 (70%) | ||

| College graduate or more | 82 (19%) | 64 (20%) | 18 (18%) | ||

| Employment status | Employed/looking for work | 78 (18%) | 55 (17%) | 23 (22%) | 0.44 |

| Unemployed | 4 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Retired | 283 (66%) | 220 (68%) | 63 (61%) | ||

| Retired because of disability | 52 (12%) | 37 (11%) | 15 (15%) | ||

| Insurance | Commercial | 89 (21%) | 62 (19%) | 27 (26%) | 0.05 |

| Government/other | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | ||

| Medicaid | 34 (8%) | 22 (7%) | 12 (12%) | ||

| Medicare | 300 (70%) | 238 (73%) | 62 (60%) | ||

| Annual household income | <$30,000 | 137 (32%) | 100 (31%) | 37 (36%) | 0.49 |

| $30,000-$59,999 | 108 (25%) | 80 (25%) | 28 (27%) | ||

| ≥$60,000 | 76 (18%) | 58 (18%) | 18 (18%) | ||

| Health literacy | Inadequate/marginal | 143 (33%) | 109 (34%) | 34 (33%) | 0.91 |

| Adequate | 284 (67%) | 215 (66%) | 69 (67%) | ||

| Physical health | |||||

| Charlson comorbidity index | Median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0-7.0) | 5.0 (3.0-6.0) | 5.0 (3.0-7.0) | 0.40 |

| CKD stage | Stages 2, 3a, and 3b (30-60) | 263 (62%) | 206 (64%) | 57 (55%) | 0.13 |

| Stage 4 (15-29) | 150 (35%) | 110 (34%) | 40 (39%) | ||

| Stage 5 (<15) | 14 (3%) | 8 (2%) | 6 (6%) | ||

| Kidney Failure Risk Equation score | High risk | 67 (16%) | 43 (13%) | 24 (23%) | 0.01 |

| Not high risk | 360 (84%) | 281 (87%) | 79 (77%) | ||

| Albumin-creatinine ratio | Median (IQR) | 97.9 (51.2-277.2) | 96.8 (51.2-261.9) | 120.5 (52.5-387.1) | 0.18 |

| Years in nephrology care | Median (IQR) | 3.8 (1.9-6.5) | 3.6 (1.8-6.2) | 4.4 (2.7-7.0) | 0.02 |

| Nephrology care/knowledge | |||||

| Patient-centeredness | Mean (SD) | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.6 (.6) | 3.7 (.4) | 0.02 |

| Kidney doctor has recommended specific treatment option | Yes | 61 (14%) | 38 (12%) | 23 (22%) | 0.001 |

| No | 204 (48%) | 171 (53%) | 33 (32%) | ||

| Satisfaction with patient–kidney team discussion of treatment options | Completely | 82 (19%) | 44 (14%) | 38 (37%) | < 0.001 |

| Mostly | 33 (8%) | 26 (8%) | 7 (7%) | ||

| Not at all/a little | 19 (4%) | 17 (5%) | 2 (2%) | ||

| No prior discussion | 292 (68%) | 236 (73%) | 56 (54%) | ||

| Kidney failure treatment modality education class | Attended | 36 (8%) | 17 (5%) | 19 (18%) | < 0.001 |

| Not attended | 390 (91%) | 306 (94%) | 84 (82%) | ||

| CKD knowledge | Median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0-6.0) | 5.0 (4.0-6.0) | 6.0 (5.0-7.0) | 0.01 |

| Psychosocial | |||||

| Depressive symptoms | At least moderate symptoms | 78 (18%) | 57 (18%) | 21 (20%) | 0.62 |

| Mild or no symptoms | 341 (80%) | 260 (80%) | 81 (79%) | ||

| Decision self-efficacy | Median (IQR) | 90.9 (77.3-100.0) | 90.9 (77.3-100.0) | 95.5 (90.9-100.0) | < 0.001 |

| Kidney self-management self-efficacy | Median (IQR) | 30.0 (26.0-35.0) | 30.0 (26.0-34.0) | 32.0 (26.0-36.0) | 0.08 |

| Informational support | Median (IQR) | 57.7 (47.6-65.6) | 56.9 (46.2-65.6) | 65.6 (51.7-65.6) | 0.002 |

| Emotional support | Median (IQR) | 62.0 (48.8-62.0) | 55.7 (47.3-62.0) | 62.0 (51.1-62.0) | 0.001 |

| Instrumental support | Median (IQR) | 63.3 (50.7-63.3) | 63.3 (50.4-63.3) | 63.3 (52.7-63.3) | 0.08 |

Note: Medians (IQR) or frequencies are shown. We assessed participant differences in decisional conflict prevalence using Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Frequencies may not total 100% because of missing data. Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; GED, general educational development; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; SURE, Sure of myself, Understand information, Risk-benefit ratio, Encouragement.

Decisional Conflict

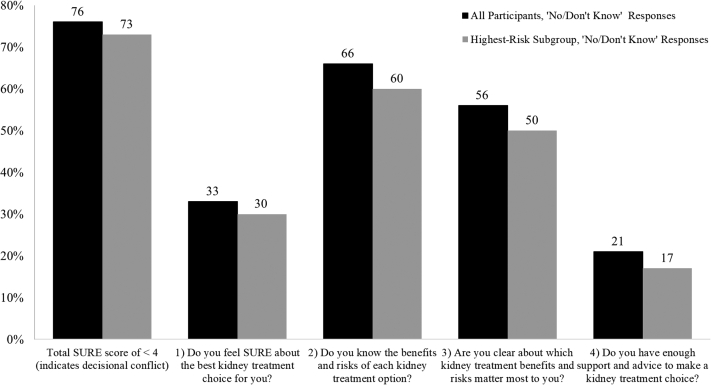

In the SURE preamble, 69% of participants chose a treatment. In-center hemodialysis was most popular (35%), followed by transplantation (29%), home hemodialysis (18%), medical management (16%), and peritoneal dialysis (2%). Seventy-six percent of participants had a score of <3, indicating decisional conflict (Fig 2). Specifically, 103 participants (24%) had a perfect score; 75 (18%) scored 3; 110 (26%), 2; 98 (23%), 1; and 41 (10%), 0. Feeling uninformed about the benefits and risks of each treatment option (66%) and feeling unclear about treatment benefits and risks of personal value (56%) contributed to decisional conflict more than feeling uncertain about the best option (33%) and feeling unsupported in making a choice (21%).

Figure 2.

Results of the 4-item SURE screening test for decisional conflict about kidney failure treatment modalities among all participants and those at highest risk of 2-year progression to kidney failure. Abbreviations: SURE, Sure of myself; Understand information; Risk-benefit ratio; Encouragement. Notes: N = 427, all participants. n = 171, highest-risk subgroup. The SURE screening test includes 4 dichotomous questions. A response of “yes” scores 1 (no decisional conflict) and a response of “no” or “don’t know” scores 0 (decisional conflict). A total SURE score of <3 indicates decisional conflict, whereas a perfect score of 4 out of 4 indicates no decisional conflict. The highest-risk subgroup had an estimated glomerular filtration rate of <30 or a 2-year Kidney Failure Risk Equation score of >10%.

Several participant characteristics differed according to SURE results (Table 1). Those with decisional conflict were more likely to be older, had a shorter duration of nephrology care, and had lower patient-centeredness, CKD knowledge, decision self-efficacy, and informational and emotional support scores. Decisional conflict was also more likely among participants with non–high-risk KFRE scores (vs high-risk), receipt of a treatment recommendation (vs no receipt), no or little satisfaction with patient–kidney team treatment discussions (vs complete), and no prior attendance of a treatment education class (vs attendance).

Associations Between Participant Characteristics and Decisional Conflict

Satisfaction with patient–kidney team treatment discussions, attendance of treatment education classes, and decision self-efficacy were independently associated with decisional conflict in the fully adjusted model. Participants completely (vs not at all or a little) satisfied with discussions and those who had (vs had not) attended treatment education classes had 84% and 62% lower odds of decisional conflict, respectively. Likewise, a 1-point increase in decision self-efficacy was associated with 3% lower odds of decisional conflict (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations of Participant Characteristics With SURE Screening Test Results Indicative of Decisional Conflict About Kidney Failure Treatment Modalities

| Characteristics | Model 1 | P | Model 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 (1.01-1.04) | < 0.01 | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) | 0.75 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 1.01 (0.65-1.59) | 0.95 | 1.17 (0.66-2.08) | 0.59 |

| Race | ||||

| Other race/ethnicity | Ref | Ref | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2.00 (0.64-6.26) | 0.23 | 1.71 (0.44-6.63) | 0.44 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married/living with partner | Ref | Ref | ||

| Married/living with partner | 1.28 (0.82-2.00) | 0.27 | 1.84 (0.99-3.44) | 0.06 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | Ref | Ref | ||

| High school graduate/GED/some college | 0.77 (0.38-1.52) | 0.45 | 0.75 (0.32-1.77) | 0.51 |

| College graduate or more | 0.93 (0.41-2.11) | 0.86 | 1.08 (0.37-3.19) | 0.88 |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed/looking for work | Ref | Ref | ||

| Retired | 1.46 (0.83-2.56) | 0.19 | 1.51 (0.67-3.38) | 0.32 |

| Retired because of disability | 1.03 (0.48-2.23) | 0.94 | 1.85 (0.63-5.41) | 0.26 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| <$30,000 | Ref | Ref | ||

| $30,000-$59,999 | 1.06 (0.60-1.87) | 0.85 | 1.05 (0.50-2.22) | 0.90 |

| ≥$60,000 | 1.19 (0.62-2.28) | 0.60 | 1.49 (0.58-3.83) | 0.41 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Commercial | Ref | Ref | ||

| Government/Other | 0.44 (0.06-3.26) | 0.42 | 1.30 (0.06-26.86) | 0.86 |

| Medicaid | 0.80 (0.35-1.84) | 0.60 | 1.05 (0.34-3.28) | 0.93 |

| Medicare | 1.67 (0.98-2.84) | 0.06 | 1.73 (0.86-3.47) | 0.13 |

| Health literacy | ||||

| Inadequate/marginal | Ref | Ref | ||

| Adequate | 0.97 (0.61-1.56) | 0.91 | 1.20 (0.65-2.19) | 0.56 |

| Physical health | ||||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.97 (0.88-1.07) | 0.51 | 0.96 (0.85-1.07) | 0.44 |

| CKD stage | ||||

| Stages 2, 3a, and 3b (30-60) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Stage 4 (15-29) | 0.76 (0.48-1.21) | 0.25 | 1.05 (0.59-1.89) | 0.87 |

| Stage 5 (<15) | 0.37 (0.12-1.11) | 0.08 | 0.54 (0.11-2.57) | 0.44 |

| Nephrology care/knowledge | ||||

| Years in nephrology care | 0.93 (0.87-0.99) | 0.03 | 0.95 (0.88-1.03) | 0.22 |

| Patient-centeredness | 0.55 (0.33-0.90) | 0.02 | 1.01 (0.56-1.82) | 0.98 |

| Kidney doctor recommended specific treatment option | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.32 (0.17-0.60) | < 0.001 | 0.52 (0.24-1.13) | 0.10 |

| Satisfied with patient–kidney team discussion of treatment options | ||||

| Not at all/a little | Ref | Ref | ||

| Mostly | 0.44 (0.08-2.36) | 0.34 | 0.51 (0.08-3.40) | 0.49 |

| Completely | 0.14 (0.03-0.63) | 0.01 | 0.16 (0.03-0.88) | 0.04 |

| Kidney failure treatment modality education class | ||||

| Not attended | Ref | Ref | ||

| Attended | 0.25 (0.12-0.49) | < 0.001 | 0.38 (0.16-0.90) | 0.03 |

| CKD knowledge | 0.80 (0.69-0.92) | < 0.01 | 0.87 (0.72-1.05) | 0.13 |

| Psychosocial | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | ||||

| Mild or no symptoms | Ref | Ref | ||

| At least moderate symptoms | 0.85 (0.48-1.48) | 0.56 | 0.69 (0.33-1.46) | 0.33 |

| Decision self-efficacy | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.94-0.99) | 0.004 |

| Kidney self-management self-efficacy | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 0.12 | 0.99 (0.94-1.04) | 0.62 |

| Informational support | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | 0.01 | 0.99 (0.95-1.02) | 0.50 |

| Emotional support | 0.96 (0.94-0.99) | 0.01 | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 0.64 |

| Instrumental support | 0.98 (0.96-1.01) | 0.13 | 1.00 (0.96-1.04) | 0.98 |

Notes: Odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals are presented. Only one indicator of kidney function (ie, eGFR) was included given the high correlation among all indicators (ie, eGFR, Kidney Failure Risk Equation score, and albumin-creatinine ratio).

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GED, general educational development; Ref, reference; SURE, Sure of myself, Understand information, Risk-benefit ratio, Encouragement.

Sensitivity Analysis

Forty percent of participants satisfied criteria for highest risk of 2-year progression to kidney failure (n = 171). The majority (96%) had an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, 39% had a high-risk KFRE score, and the median (IQR) albumin-creatinine ratio was 159.4 (68.3-643.3). Participant characteristics that differed by SURE results in the full sample persisted in the highest-risk subgroup with the exception of age and informational and emotional support, although the direction of associations remained consistent. Insurance status also differed by decisional conflict; highest-risk participants were more likely to report decisional conflict with Medicare coverage, a pattern evident in the full sample (Table S2).

Compared with the full sample, treatment selections in the SURE preamble increased by 7% and preferences were similar (35% chose in-center hemodialysis; 34%, transplantation; 16%, home hemodialysis; 12%, medical management; and 2%, peritoneal dialysis). Overall decisional conflict prevalence decreased by 3% and affirmative responses for individual SURE items increased by 3%-6% (Fig 2). Specifically, 47 participants (27%) had a perfect score; 36 (21%) scored 3; 40 (23%), 2; 38 (22%), 1; and 10 (6%), 0.

In the fully adjusted model, treatment education and decision self-efficacy remained associated with lower odds of decisional conflict. Of note, the association between receipt of a treatment recommendation and decisional conflict increased in magnitude. Participants with (vs without) a recommendation had 74% lower odds of reporting decisional conflict (Table S3).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of adults with advanced CKD, 76% reported decisional conflict about kidney failure treatment modalities. Complete satisfaction with patient–kidney team treatment discussions, attendance of treatment educational classes, and greater decision self-efficacy were associated with lower odds of decisional conflict above and beyond sociodemographic, physical health, nephrology care/knowledge, and psychosocial characteristics. We observed similar results among a subset of participants at highest risk of 2-year progression to kidney failure. These findings highlight the difficulty adults with advanced CKD experience in contemplating kidney failure treatment, even when expected to reach kidney failure and targeted by clinical practice guidelines for treatment preparation. Our findings also provide insight into the potential timing and targets of intervention efforts aimed at mitigating decisional conflict.

Our study is the first to administer SURE to CKD outpatients in the United States who had not previously implemented a kidney failure treatment decision. The high decisional conflict prevalence observed here, irrespective of CKD progression risk, warrants nephrologists’ consideration of incorporating SURE into treatment-related discussions. SURE is uniquely intended for such purposes; whereas other decisional conflict measures are research-oriented, SURE was developed for the clinical setting.17,21,22 Another beneficial feature of SURE is its applicability to all decision-making stages, which allows nephrologists to treat treatment decision-making as a dynamic process, rather than a singular event. It also leaves appropriate measurement timing to nephrologists’ discretion, allowing them to account for patients’ decision readiness and prognosis. Given that SURE items reflect modifiable factors contributing to decision uncertainty,24 administering SURE earlier in the disease course may be particularly useful. Earlier administration affords nephrologists time to assess specific decisional needs, provide targeted decision support, and readminister SURE on a routine basis at later decision-making stages to assess changes in decisional conflict. Further, the brief addition of SURE stands to not only decrease decisional conflict but facilitate its positive and reduce its negative downstream effects.

Our study also brings attention to the uptake of current KDIGO clinical practice guidelines. These guidelines suggest decisional conflict prevalence should have been substantially lower in highest-risk participants because of greater engagement in treatment preparation. Instead, we detected little variation in the endorsement of SURE items and demonstrated comparable, suboptimal characteristics with respect to receipt of a treatment recommendation, engagement in patient–kidney team treatment discussions, attendance of treatment education classes, and CKD knowledge scores. One potential explanation for similarities across CKD progression risk is that guidelines are not being followed. Alternatively, guidelines may be being followed, but ineffectively, because of lack of psychosocial support and patient navigation to facilitate follow-through with nephrologists’ recommendations.1 Future research is needed to understand whether these explanations or others can account for incongruence between practice recommendations and patient-reported treatment preparation.

Additionally, we examined a broad range of correlates to help guide intervention and practice. This approach enabled identification of novel nephrology care characteristics relevant for decisional conflict, specifically satisfaction with patient–kidney team discussions in the full sample and receipt of a treatment recommendation in the highest-risk subgroup. The relevance of different care characteristics at different risk levels likely reflects varying decisional needs, serving as a reminder that goals, priorities, values, and preferences change as CKD progresses.43 For instance, individuals at increased risk of kidney failure contemplate options in more time-sensitive circumstances; therefore, they may want nephrologists to play a more paternalistic role than those in earlier disease stages with more time for repeated, collaborative treatment discussions. To better understand the relationship between communication-based nephrology care characteristics and decisional conflict, decisional conflict should be measured in studies on patient–kidney team communication. Relatedly, future research is needed to identify factors that constitute satisfactory treatment discussions along the CKD continuum. Notably, however, 68% of all participants and 54% of highest-risk participants reported that they and their kidney team had never discussed treatment options; patients cannot be satisfied with discussions that do not take place. Infrequent discussion occurrence is concerning given that all participants had a high-risk prognosis, and highest-risk participants should have been targeted for treatment preparation. We propose nephrologists buck the trend of avoiding earlier treatment discussions by using available person-centered communication tools to help them prepare for and initiate treatment discussions that may, in turn, reduce decisional conflict.1,9,43, 44, 45

Further, we extended prior work linking receipt of treatment education and greater decision self-efficacy to less decisional conflict. To our knowledge, these associations have only been observed in Taiwanese kidney failure patients scheduled to start dialysis.15 We showed that these associations are applicable to US outpatients, treatment options inclusive of transplantation, and both earlier and later stages of CKD. Our findings indicate that simultaneously targeting treatment education class attendance and confidence in treatment decision-making might be a promising intervention strategy for mitigating decisional conflict. This strategy may involve tailoring educational resources and decision support interventions to different levels of decision self-efficacy.15 Decision self-efficacy–enhancing strategies can also be incorporated into the design of educational resources and decision support interventions.15 Based on the Decision Self-Efficacy scale used in this study,38 special consideration should be given to building confidence in acquiring and understanding treatment information, clarifying values, communicating openly and honestly with the kidney team, handling unwanted decision pressure, and deferring decisions when more time is needed. Decision self-efficacy–enhancing strategies have been used in decision support interventions developed for other chronic disease populations with significant improvements in decisional conflict, decision self-efficacy, and disease knowledge alike.46, 47, 48 These efforts could provide guidance and adaptation possibilities for similar interventions in advanced CKD.

Limitations of this study warrant mention. The PREPARE NOW study was conducted in a single-health system in Pennsylvania where the patient population is largely older, non-Hispanic White, and rural; therefore, our findings may not generalize to other groups. Although PREPARE NOW participants had advanced CKD, and those in our subgroup analysis had an increased risk of 2-year progression to kidney failure, we cannot be certain about the imminent nature of treatment decisions. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of our analysis precludes conclusions about causation and examination of how exposure timing relates to decisional conflict. Further, although SURE was intentionally streamlined for convenient use in clinical practice, its binary response format may simplify the complex experience of decisional conflict.49 PREPARE NOW investigators added a “don’t know” response category in an attempt to address this potential limitation. Relatedly, previous studies have identified potential limitations of SURE (eg, sex differences)50; however, their relevance to CKD will remain unclear without further research. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study has achieved new insights, extended previous findings, and provided directions for future research, intervention, and practice.

In summary, decisional conflict about kidney failure treatment was highly prevalent among US outpatients with advanced CKD regardless of their risk of kidney failure. We identified patient–kidney team treatment discussion characteristics, attendance of treatment education classes, and greater decision self-efficacy as potentially important intervention targets for reducing decisional conflict. Findings highlight a need to minimize the mismatch between current practice recommendations and patient-reported engagement in treatment preparation, facilitate patient–kidney team participation in treatment discussions, and incorporate decision self-efficacy–enhancing strategies into decision support mechanisms.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Nicole DePasquale, PhD, MSPH, Jamie A. Green, MD, Patti L. Ephraim, MPH, Sarah Morton, MB, Sarah B. Peskoe, PhD, Clemontina A. Davenport, PhD, Dinushika Mohottige, MD, MPH, Lisa McElroy, MD, MS, Tara S. Strigo, MPH, Felicia Hill-Briggs, PhD, ABPP, Teri Browne, PhD, MSW, Jonathan Wilson, MS, LaPricia Lewis-Boyer, CCRP, Ashley N. Cabacungan, BS, and L. Ebony Boulware, MD, MPH.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: ND, JAG, PLE, LEB; data analysis: ND, PLE, SM, SBP, CAD, LEB; intellectual contributions/interpretation: ND, JAG, PLE, SM, SBP, CAD, DM, LM, TSS, FFH-B, TB, JW, LL-B, ANC, LEB; supervision or mentorship: JAG, PLE, LEB. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Project Program Award (IHS-1409-20967). Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01AG070284 (Dr DePasquale).

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the physicians, nurses, medical assistants, staff, and patients of the Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pennsylvania.

Disclaimer

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, its Board of Governors, or Methodology committee, nor those of the National Institutes of Health.

Peer Review

Received January 18, 2022. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input by the Statistical Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form June 5, 2022.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Table S1: Comparison of Characteristics Between PREPARE NOW Participants With and Without Complete Data on the SURE Screening Test for Decisional Conflict.

Table S2: Characteristics of the Highest-Risk Subgroup Overall and According to SURE Screening Test Results for Decisional Conflict About Kidney Failure Treatment Modalities.

Table S3: Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations of Highest-Risk Participant Characteristics With SURE Screening Test Results Indicative of Decisional Conflict About Kidney Failure Treatment Modalities.

Supplementary Material

Tables S1-S3.

References

- 1.Green J.A., Boulware L.E. Patient education and support during CKD transitions: when the possible becomes probable. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016;23(4):231–239. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DePasquale N., Cabacungan A., Ephraim P.L., et al. “I Wish Someone Had Told Me That Could Happen”: a thematic analysis of patients’ unexpected experiences with end-stage kidney disease treatment. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(4):577–586. doi: 10.1177/2374373519872088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho Y.F., Li I.C. The influence of different dialysis modalities on the quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease: a systematic literature review. Psychol Health. 2016;31(12):1435–1465. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2016.1226307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purnell T.S., Auguste P., Crews D.C., et al. Comparison of life participation activities among adults treated by hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):953–973. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koch-Weser S., Porteny T., Rifkin D.E., et al. Patient education for kidney failure treatment: a mixed-methods study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78(5):690–699. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.02.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DePasquale N., Cabacungan A., Ephraim P.L., Lewis-Boyér L., Powe N.R., Boulware L.E. Family members’ experiences with dialysis and kidney transplantation. Kidney Med. 2019;1(4):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DePasquale N., Cabacungan A., Ephraim P.L., Lewis-Boyér L., Powe N.R., Boulware L.E. Perspectives of African-American family members about kidney failure treatment. Nephrol Nurs J. 2020;47(1):53–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griva K., Li Z.H., Lai A.Y., Choong M.C., Foo M.W. Perspectives of patients, families, and health care professionals on decision-making about dialysis modality—the good, the bad, and the misunderstandings. Perit Dial Int. 2013;33(3):280–289. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2011.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noble H., Brazil K., Burns A., et al. Clinician views of patient decisional conflict when deciding between dialysis and conservative management: qualitative findings from the PAlliative Care in chronic Kidney diSease (PACKS) study. Palliat Med. 2017;31(10):921–931. doi: 10.1177/0269216317704625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keeney R.L. Decision analysis: an overview. Oper Res. 1982;30(5):803–838. doi: 10.1287/opre.30.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connor A.M., Jacobsen M.J., Stacey D. An evidence-based approach to managing women's decisional conflict. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;31(5):570–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2002.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor A.M. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15(1):25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McPherson L., Basu M., Gander J., et al. Decisional conflict between treatment options among end-stage renal disease patients evaluated for kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(7) doi: 10.1111/ctr.12991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vélez-Bermúdez M., Christensen A.J., Kinner E.M., Roche A.I., Fraer M. Exploring the relationship between patient activation, treatment satisfaction, and decisional conflict in patients approaching end-stage renal disease. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(9):816–826. doi: 10.1093/abm/kay091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen N.H., Lin Y.P., Liang S.Y., Tung H.H., Tsay S.L., Wang T.J. Conflict when making decisions about dialysis modality. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(1-2):e138–e146. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goh ZZS, Chia JMX, Seow TY, et al. Treatment-related decisional conflict in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients in Singapore: prevalence and determinants. Br J Health Psychol. Published online December 5, 2021. 10.1111/bjhp.12577 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Garvelink M.M., Boland L., Klein K., et al. Decisional conflict scale use over 20 years: the anniversary review. Med Decis Making. 2019;39(4):301–314. doi: 10.1177/0272989X19851345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan E.G.F., Teo I., Finkelstein E.A., Meng C.C. Determinants of regret in elderly dialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 2019;24(6):622–629. doi: 10.1111/nep.13400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green J.A., Ephraim P.L., Hill-Briggs F.F., et al. Putting patients at the center of kidney care transitions: PREPARE NOW, a cluster randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;73:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin A., Stevens P.E., Bilous R.W., et al. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1):1–50. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Légaré F., Kearing S., Clay K., et al. Are you SURE?: assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4-item screening test. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(8):e308–e314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferron Parayre A., Labrecque M., Rousseau M., Turcotte S., Légaré F. Validation of SURE, a four-item clinical checklist for detecting decisional conflict in patients. Med Decis Making. 2014;34(1):54–62. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13491463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor A.M. User Manual - Decisional Conflict Scale. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decisional_Conflict.pdf Published 1993. Updated 2010.

- 24.O’Connor A.M., Tugwell P., Wells G.A., et al. A decision aid for women considering hormone therapy after menopause: decision support framework and evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33(3):267–279. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saggi S.J., Allon M., Bernardini J., et al. Considerations in the optimal preparation of patients for dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(7):381–389. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis J.L., Davison S.N. Hard choices, better outcomes: a review of shared decision-making and patient decision aids around dialysis initiation and conservative kidney management. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;26(3):205–213. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chew L.D., Bradley K.A., Boyko E.J. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace L.S., Rogers E.S., Roskos S.E., Holiday D.B., Weiss B.D. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):874–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charlson M., Szatrowski T.P., Peterson J., Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levey A.S., Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H., et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tangri N., Grams M.E., Levey A.S., et al. Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):164–174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tangri N., Stevens L.A., Griffith J., et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gansevoort R.T., Matsushita K., Van Der Velde M., et al. Lower estimated GFR and higher albuminuria are associated with adverse kidney outcomes. A collaborative meta-analysis of general and high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int. 2011;80(1):93–104. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart M., Meredith L., Ryan B.L. 04-1. Western University; 2004. (The Patient Perception of Patient-Centeredness Questionnaire (PPPC), Vol). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart M., Brown J.B., Donner A., et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright J.A., Wallston K.A., Elasy T.A., Ikizler T.A., Cavanaugh K.L. Development and results of a kidney disease knowledge survey given to patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(3):387–395. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroenke K., Strine T.W., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., Berry J.T., Mokdad A.H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Connor A.M. User Manual - Decision Self-Efficacy Scale. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decision_SelfEfficacy.pdf Published 1995. Updated 2002.

- 39.Wild M.G., Wallston K.A., Green J.A., et al. The Perceived Medical Condition Self-Management Scale can be applied to patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017;92(4):972–978. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Informational support: a brief guide to the PROMIS Informational Support instruments. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Informational_Support_Scoring_Manual.pdf Published July 8, 2015.

- 41.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Emotional support: a brief guide to the PROMIS Emotional Support instruments. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Emotional_Support_Scoring_Manual.pdf Published July 8, 2020. Accessed XXXX.

- 42.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Instrumental support: a brief guide to the PROMIS Instrumental Support instruments. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Instrumental_Support_Scoring_Manual.pdf Published November 28, 2017.

- 43.Lu E., Chai E. Kidney supportive care in peritoneal dialysis: developing a person-centered kidney disease care plan. Kidney Med. 2022;4(2) doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Hare A.M., Rodriguez R.A., Bowling C.B. Caring for patients with kidney disease: shifting the paradigm from evidence-based medicine to patient-centered care. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(3):368–375. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schell J.O., Arnold R.M. NephroTalk: communication tools to enhance patient-centered care. Semin Dial. 2012;25(6):611–616. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang T.J., Chiu P.P., Chen K.K., Hung L.P. Efficacy of a decision support intervention for reducing decisional conflict in patients with elevated serum prostate-specific antigen: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;50 doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bailey R.A., Pfeifer M., Shillington A.C., et al. Effect of a patient decision aid (PDA) for type 2 diabetes on knowledge, decisional self-efficacy, and decisional conflict. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1262-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allen J.D., Mohllajee A.P., Shelton R.C., Drake B.F., Mars D.R. A computer-tailored intervention to promote informed decision making for prostate cancer screening among African American men. Am J Mens Health. 2009;3(4):340–351. doi: 10.1177/1557988308325460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garvelink M.M., Boland L., Klein K., et al. Decisional Conflict Scale findings among patients and surrogates making health decisions: part II of an anniversary review. Med Decis Making. 2019;39(4):316–327. doi: 10.1177/0272989X19851346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boland L., Légaré F., McIsaac D.I., et al. SURE test accuracy for decisional conflict screening among parents making decisions for their child. Med Decis Making. 2019;39(8):1010–1018. doi: 10.1177/0272989X19884541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1-S3.