ABSTRACT

Background

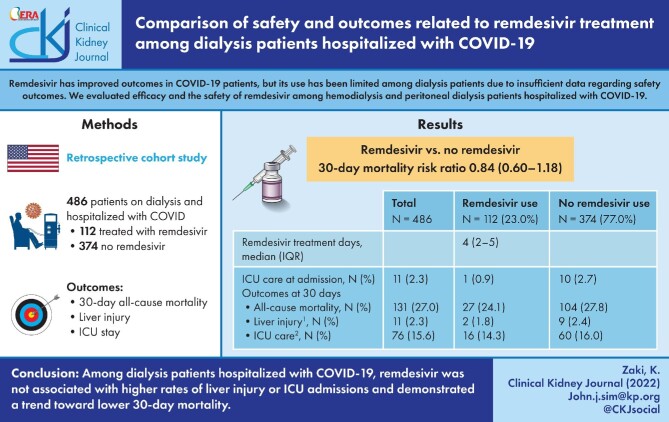

Patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) are highly susceptible to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection and its complications. Remdesivir has improved outcomes in COVID-19 patients but its use has been limited among ESKD patients due to insufficient data regarding safety outcomes. We sought to evaluate the safety of remdesivir among dialysis patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted among patients age ≥18 years on maintenance dialysis and hospitalized with COVID-19 between 1 May 2020 and 31 January 2021 within an integrated health system who were treated or not treated with remdesivir. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes were intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and transaminitis (AST/ALT >5× normal). Pseudo-populations were created using inverse probability of treatment weights with propensity scoring to balance patient characteristics among the two groups. Multivariable Poisson regression with robust error was performed to estimate 30-day mortality risk ratio.

Results

A total of 486 (407 hemodialysis and 79 peritoneal dialysis) patients were hospitalized with COVID-19, among which 112 patients (23%) were treated with remdesivir [median treatment four days (interquartile range 2–5)]. The 30-day mortality rate was 24.1% among remdesivir-treated and 27.8% among non-treated patients. The estimated 30-day mortality rate was 0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.52–1.05) among remdesivir treated compared with non-treated patients. Liver injury and ICU admission rates were 1.8% and 14.3% among remdesivir-treated patients compared with 2.4% and 16% among non-treated patients.

Conclusion

Among dialysis patients hospitalized with COVID-19, remdesivir was not associated with higher rates of liver injury or ICU admissions, and demonstrated a trend toward lower 30-day mortality.

Keywords: COVID-19, end-stage kidney disease, outcomes, Remdesivir, safety

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) represent a population that is highly vulnerable to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). They are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality from COVID-19, with mortality rates as high as 20%–30% [1–5]. Despite this greater risk, large-scale data evaluating the safety and efficacy of therapies such as remdesivir among this population have been limited.

Remdesivir was among the first investigational drugs used in the treatment of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19. It is a pro-drug that, once converted into its active metabolite, interferes with viral RNA replication [6]. Clinical trial data evaluating the safety and efficacy of remdesivir in the treatment of COVID-19 have demonstrated favorable outcomes, especially among hospitalized patients [7–9]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized, and subsequently, approved the use of remdesivir for COVID-19 based in part on this information. However, patients with advanced CKD or ESKD were largely excluded from the remdesivir clinical trials [7, 10, 11].

Remdesivir clinical trials excluded patients with advanced CKD where there is a paucity of data evaluating its pharmacokinetics in patients with renal impairment. Consequently, the FDA did not recommend the use of remdesivir in adult patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 [12]. Several safety concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of remdesivir in patients with impaired renal function due to the accumulation of its metabolites, or buildup of sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin (SCEBD), the solubilizing excipient in intravenous remdesivir [13].

Using a real-world population within an integrated health system, we sought to assess the safety of remdesivir in ESKD patients by comparing 30-day mortality, transaminitis and intensive care unit (ICU) admission among ESKD patients on dialysis hospitalized with COVID-19 that were treated with remdesivir.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study within the Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) health system. KPSC is an integrated health system that encompasses 15 medical centers and over 200 medical offices across Southern California. The patient population within KPSC is racially and ethnically diverse and is generally reflective of patients across Southern California [14]. All sociodemographic and clinical information was extracted from KPSC's integrated electronic health record unless otherwise stated. All data included in the study were collected as part of routine clinical encounters and were obtained electronically. This study was approved by the KPSC Institutional Review Board (IRB) and exempted from informed consent (IRB # 036 591).

The study population included patients ≥18 years old receiving outpatient renal replacement therapy (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) prior to admission and hospitalized with COVID-19 between 1 May and 31 January 2021. Renal replacement therapy status was obtained through the KPSC renal registry (Renal Business Group). Hospitalization was defined as an observation stay or inpatient admission with a COVID-19 International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code U07.1 and a positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction test within 14 days prior to and up to 2 days after admission date. Patients with evidence of transaminitis defined as AST and/or ALT values ≥5× upper limit of normal (AST ≥200 U/L or ALT ≥270 U/L) on presentation were excluded.

The primary exposure was remdesivir treatment during hospitalization, defined as receipt of at least one dose of remdesivir. As there was no standardization of use in remdesivir within the dialysis population, its use has been largely left up to the discretion of the treatment provider. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included intensive care unit (ICU) stay, or evidence of new transaminitis, defined as AST and/or ALT values ≥5× upper limit of normal (see reference ranges above).

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were presented as mean with standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, or frequencies (N) with percentages (%) for categorical variables. Differences between baseline characteristics were compared using χ² test for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. Kaplan–Meier curves were created to show the probability of all-cause mortality within 30 days of hospital admission, stratified by treatment with remdesivir or no remdesivir.

To minimize bias from nonrandomization, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the stabilized propensity score was performed to create a pseudo-population with balanced confounders between the two groups. Propensity score representing the probability of receiving treatment with remdesivir was created using logistic regression adjusted for the pre-defined factors including age, gender, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), inpatient/ICU status, time interval between COVID-19 testing date and hospitalization admission date, number of Elixhauser comorbidities [15] and dialysis modality. Absolute standardized mean differences were used to assess the balance of the two groups before and after IPTW. A difference <0.2 was suggestive of adequate balance [16]. Multivariable Poisson regression with robust error variances was performed among the pseudo-population to estimate the rate ratio (RR) of 30-day all-cause mortality after further adjustment the treatment or medical condition during hospitalization including maximal oxygen requirement, steroid, convalescent plasma, anticoagulation, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) and combined anakinra/tocilizumab use. In addition, to account for potential differences in COVID-19 infection severity, a sensitivity analysis was performed restricted to patients who were hospitalized in a non-observation unit. A separate pseudo-population was created by IPTW with propensity scores in this sub-group to assess the associations between 30-day all-cause mortality and remdesivir.

Among those treated with remdesivir, a secondary analysis was conducted evaluating the RR of 30-day all-cause mortality with a one day increase in remdesivir treatment duration. Additional adjustments included in the secondary analysis included age, gender, race/ethnicity, statin, convalescent plasma and ACEI/ARB use during hospitalization.

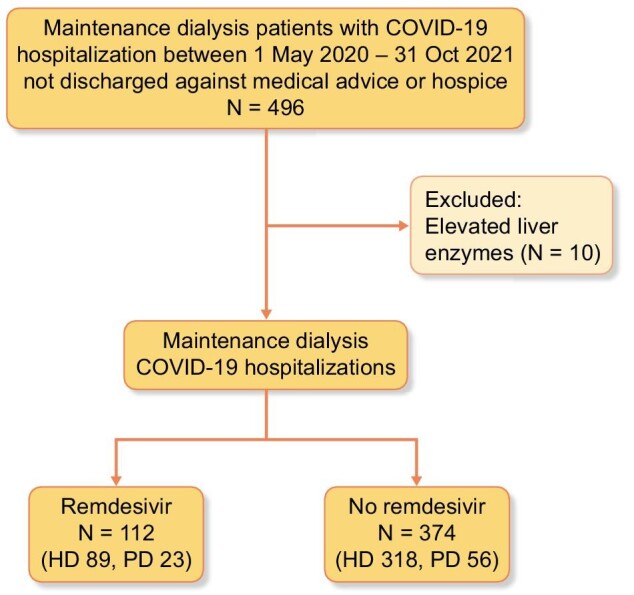

RESULTS

We identified a total of 496 patients receiving outpatient maintenance dialysis that were hospitalized with COVID-19 between 1 May 2020 and 31 January 2021. Ten patients were excluded due to transaminitis on presentation. A total of 486 patients were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

Flow chart of the study population selection. Four-hundred and ninety-six patients on outpatient renal replacement therapy were hospitalized with COVID-19 between 1 May 2020 and 31 January 2021, and not discharged against medical advice or to hospice care. Ten patients were excluded due to severely elevated liver function tests, defined as AST and/or ALT values ≥5× upper limit of normal. Of the 486 patients who met inclusion criteria, 112 patients received remdesivir treatment. *Hospitalization is defined as first observation stay or inpatient admission that was not discharged against medical advice or to hospice care.

A total of 112 patients (23.0%) were treated with remdesivir, where 46% (N = 51) initiated the remdesivir treatment on the day of admission and 44% (N = 49) initiated treatment on the second day of admission. The median treatment was 4 days (IQR 2–5). Among remdesivir-treated patients, 20.5% of patients were on peritoneal dialysis.

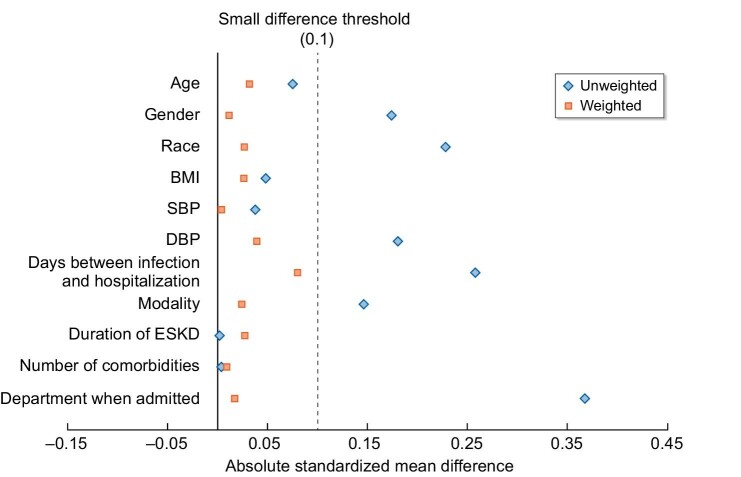

The mean age of the study population was 63.8 ± 14.5 years, with 63.8% male, 63.0% Hispanic, 12.6% Black, 12.3% Asian and 10.1% non-Hispanic White. The mean BMI was 29.7 ± 7.4 kg/m2. A total of 407 patients (83.7%) were on hemodialysis and 79 patients (16.3%) were on peritoneal dialysis. The care setting among hospitalized patients included 119 (24.5%) observation stays and 367 (75.5%) regular inpatient admissions. Medications administered during hospitalization included corticosteroids (80.2%), anticoagulation prophylaxis (72.2%), statins (66.7%) and ACEI (31.5%). The median number of Elixhauser comorbidities was 8 (IQR 6–10). Steroids were administered for 80.2% of the population, with 92.0% among remdesivir patients compared with 78.7% among non-remdesivir-treated patients during hospitalization (P = .001) (Table 1). There were no differences between dialysis duration or dialysis modality among the cohort. Among the pseudo-population utilizing IPTW with balanced demographic and clinical characteristics, all standardized mean differences were <0.2, suggestive of adequate balance between the two groups (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Total | Remdesivir | No remdesivir | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics1 | N = 486 | N = 112 | N = 374 | P-value |

| Age at admission, years, mean ± SD | 63.8 ± 14.5 | 64.6 ± 13.8 | 63.6 ± 14.7 | .48 |

| Gender, N (%) | .73 | |||

| Female | 176 (36.2) | 39 (34.8) | 137 (36.6) | |

| Male | 310 (63.8) | 73 (65.2) | 237 (63.4) | |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | .44 | |||

| White | 49 (10.1) | 13 (11.6) | 36 (9.6) | |

| Black | 61 (12.6) | 10 (8.9) | 51 (13.6) | |

| Asian | 60 (12.3) | 19 (17) | 41 (11) | |

| Hispanic | 306 (63.0) | 68 (60.7) | 238 (63.6) | |

| Other | 10 (2.1) | 2 (1.8) | 8 (2.2) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 29.7 ± 7.4 | 29.4 ± 7.51 | 29.8 ± 7.4 | .53 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg, median (IQR) | ||||

| Systolic | 141 (121.0–157.0) | 139 (121.0–156.0) | 141.5 (121.0–157.5) | .51 |

| Diastolic | 65 (58.0–81.0) | 65 (56.0–76.0) | 69 (58.0–81.0) | .06 |

| Interval days between positive lab test and hospitalization, median (IQR) | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–5) | .07 |

| Number of Elixhauser comorbidities, median (IQR) | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–10) | .65 |

| Modality type at admission, N (%) | .16 | |||

| Hemodialysis | 407 (83.7) | 89 (79.5) | 318 (85.1) | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 79 (16.3) | 23 (20.6) | 56 (15.0) | |

| Duration of patients on ESKD (ESKD duration, years) | 4.4 ± 3.6 | 4.4 ± 3.3 | 4.4 ± 3.7 | .58 |

| Care setting, N (%) | .0019 | |||

| Observation | 119 (24.5) | 15 (13.4) | 104 (27.8) | |

| Inpatient | 367 (75.5) | 97 (86.6) | 270 (72.2) | |

| Oxygen requirement on admission, N (%) | .058 | |||

| Room air | 65 (13.4) | 8 (7.1) | 57 (15.2) | |

| Low flow/supplemental oxygen | 283 (58.2) | 65 (58) | 218 (58.3) | |

| High flow/BiPAP | 72 (14.8) | 23 (20.5) | 49 (13.1) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 66 (13.6) | 16 (14.3) | 50 (13.4) | |

| Medication use during hospitalization, N (%) | ||||

| ACEI/ARB | 153 (31.5) | 42 (37.5) | 111 (29.7) | .12 |

| Anakinra | 55 (11.3) | 7 (6.3) | 48 (12.8) | .05 |

| Anticoagulation | 63 (13.0) | 11 (9.8) | 52 (13.9) | .23 |

| Anticoagulation prophylaxis | 351 (72.2) | 87 (77.7) | 264 (70.6) | .16 |

| Bamlanivimab | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) | .44 |

| Baricitinib | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | .36 |

| Convalescent plasma | 86 (17.7) | 23 (20.5) | 63 (16.8) | .32 |

| Statin | 324 (66.7) | 76 (67.9) | 248 (66.3) | .70 |

| Steroids | 390 (80.2) | 103 (92.0) | 287 (76.7) | .001 |

| Tocilizumab | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.8) | .35 |

Figure 2:

Standardized mean difference comparison of risk factors for receiving remdesivir before and after IPTW. Propensity score representing the probability of receiving treatment with remdesivir was created using logistic regression adjusted for the pre-defined factors including age, gender, race/ethnicity, BMI, inpatient/ICU status, number of Elixhauser comorbidities and dialysis modality.

Outcomes

The 30-day all-cause mortality among the total cohort was 131 patients (27.0%). Among remdesivir-treated patients, 27 (24.1%) patients died compared with 104 (27.8%) in non-remdesivir-treated patients. The survival plot of all-cause mortality by remdesivir treatment status up to 30 days are presented in Supplementary Fig. S1. New onset transaminitis was observed in two patients (1.8%) who received remdesivir, and nine patients (2.4%) who did not receive remdesivir. Rates of ICU care (including patients directly admitted to the ICU) among the remdesivir-treated and non-treated patients were 16 (14.3%) versus 60 (16.0%), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2:

Outcomes among dialysis patients hospitalized patients with COVID-19 treated with and without remdesivir.

| Total | Remdesivir use | No remdesivir use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 486 | N = 112 (23.0%) | N = 374 (77.0%) | |

| Remdesivir treatment days, median (IQR) | 4 (2–5) | ||

| ICU care at admission, N (%) | 11 (2.3) | 1 (0.9) | 10 (2.7) |

| Outcomes at 30 days | |||

| All-cause mortality, N (%) | 131 (27.0) | 27 (24.1) | 104 (27.8) |

| Liver injurya, N (%) | 11 (2.3) | 2 (1.8) | 9 (2.4) |

| ICU careb, N (%) | 76 (15.6) | 16 (14.3) | 60 (16.0) |

AST ≥200 U/L and/or ALT ≥270 U/L.

bIncludes patients directly admitted to ICU.

To minimize indication bias between treated and non-treated groups, a pseudo-population was created using IPTW that resulted in balanced characteristics since all standardized mean differences were <0.2 (Supplementary Table S1). The RR of 30-day all-cause mortality among remdesivir-treated patients was 0.74 (95% CI 0.52–1.05) compared with non-treated patients after further adjustment for time-varying confounders during hospitalization which included inpatient-administered medications and maximal oxygen requirement (Table 3). Similar findings were observed among patients who were hospitalized in a non-observation unit [RR 0.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.60–1.18]. In a secondary analysis, the adjusted RR of 30-day all-cause mortality with a one-day increase of remdesivir treatment (among those treated with remdesivir) was 0.99 (95% CI 0.78–1.25) (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 3:

RR of all-cause mortality among dialysis patients receiving remdesivir after COVID-19 infection.

| Among all study population (N = 486) | Among those who were hospitalized in non-observation unitb (N = 367) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality within 30 days, N (%) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusteda RR (95% CI) | All-cause mortality within 30 days, N (%) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusteda RR (95% CI) | |

| No remdesivir treatment | 104 (27.8) | Reference | 88 (32.6) | Reference | ||

| Treated by remdesivir | 27 (24.1) | 0.83 (0.56–1.22) | 0.74 (0.52–1.05) | 26 (26.8) | 0.90 (0.62–1.30) | 0.84 (0.60–1.18) |

aAdjust for maximal oxygen during hospitalization, using steroids, convalescent plasma, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), assist control (AC), and combined anakinra/tocilizumab during hospitalization.

bNon-observation unit refers to regular hospital ward instead of observation unit where patients were hospitalized with expectation that they would be discharged home within 4 h.

DISCUSSION

In a diverse cohort of ESKD patients on maintenance dialysis hospitalized for COVID-19, the rate of mortality outcomes, transaminitis and ICU admission did not appear different between remdesivir treated and non-treated groups. Additionally, we observed a trend towards lower mortality among dialysis patients treated with remdesivir. Given that the dialysis population has one of the highest COVID-19 mortality rates but has been largely excluded from COVID-19 treatment clinical trials, our findings may help provide assurance for providers prescribing remdesivir for COVID-19 in the dialysis population. This is particularly meaningful given the significant morbidity and mortality associated with this vulnerable population [1–5].

Patients with chronic or end-stage kidney disease are among the highest risk for hospitalization, severe illness, and death related to COVID-19 [3, 17]. Real-world clinical observations point to a mortality rate 10- to 20-fold higher in patients with severe renal disease compared with the general population [3]. In a retrospective cohort study of 133 ESKD dialysis patients with COVID-19 within the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health system, 57% of the patients required hospitalization, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 33% and overall mortality of 23% [3]. Similarly, in another large US study of over 10 000 hospitalized COVID-19 patients, those with ESKD had a higher rate of in-hospital death compared with those without (31.7% versus 25.4%, odds ratio 1.38, 95% CI 1.12–1.70) [17].

Despite higher morbidity and mortality, patients with advanced kidney disease have often been excluded from pandemic-related clinical studies, limiting access to potentially effective therapies for this vulnerable population. Among those potentially beneficial treatment options is remdesivir. Early clinical trial data from the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACCT-1) demonstrated a reduction in median recovery time among patients treated with a 10-day course of remdesivir compared with placebo (11 versus 15 days, RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.12–1.49; P < .001) [7]. Furthermore, remdesivir use was associated with a trend towards reduced mortality, although there was no statistically significant effect [7]. Other randomized control trials established the effectiveness of remdesivir on clinical outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, including length of hospital stay, time to recovery and reduction in serious adverse events [10, 11, 18]. In addition, there is emerging evidence that early remdesivir treatment in the outpatient setting may prevent progression to severe disease. More recently published trial data demonstrated that compared with placebo, a 3-day course of remdesivir in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19 resulted in an 87% lower risk of hospitalization or death [8]. However, these clinical trials excluded patients with severe renal insufficiency or those on dialysis.

Despite its modest beneficial effects, remdesivir remains among the few FDA-approved treatments available for use in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Though it was initially authorized for use in severe disease, its use has since expanded to include all hospitalized patients, irrespective of disease severity [19]. However, the FDA did not recommend use of the drug in patients with severely impaired renal function (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2), citing a lack of pharmacokinetic data in patients with renal impairment, in addition to concerns about the accumulation and potential toxicity of the excipient SCEBD, which is renally cleared [12].

Remdesivir is rapidly converted to its active drug form and thus exhibits minimal renal excretion (<10%). The active metabolite GS-441 524, considered the remdesivir nucleoside core, is renally excreted, with levels of approximately 50% found in the urine [13]. However, the implications of this finding are not clear, and has not been directly correlated to hepatic or renal toxicity. Furthermore, a pharmacokinetic study evaluating the renal excretion of remdesivir and its associated metabolites in patients on intermittent hemodialysis found that hemodialysis reduced GS-441 524 plasma concentrations by about 50%. Trough concentrations of GS-441 524 were high but stable between dialysis sessions (range 1.66–1.79 µg/mL), while remdesivir trough concentrations were always below the lower limit of quantification [20]. Regarding the excipient SCEBD, accumulation can occur in renal failure, however reported toxic doses were 50–100 times higher in animal models than what would be given in patients on a 5- or 10-day course of remdesivir [20]. Furthermore, SCEBD is likewise eliminated by renal replacement therapy, thereby ameliorating the risk of accumulation and potential toxicity [6, 20].

There are also several potential limitations that may confound the interpretation of our findings. Despite attempts to adjust for differences in receiving remdesivir treatment, there was likely residual confounding from indication biases. Although we followed all patients from the day of hospital admission, few patients started receiving remdesivir as late as hospital day 5 (n = 1), which could potentially contribute to immortal bias. The actual timing of remdesivir administration in relation to hemodialysis is not established and was variable among our population. The time interval from hospitalization/symptom duration to initiation of remdesivir was not available for the entire study population, though it may affect treatment efficacy. However, we did include the time interval between the COVID-19-positive test date and hospital admission date in the model when creating propensity scores [21]. Because 90% of patients who had remdesivir administrated initiated treatment on the same day or next day of hospital admission, we feel that the immortal bias should be minimal. We also did not have comprehensive information in terms of the severity of COVID-19. We did use clinical measurements such as oxygenation status and blood pressure on admission as surrogates. The majority of patients in both groups did receive steroids, which also may be considered an indicator of clinical severity. Finally, while both groups had similar dialysis vintage, we did not have information on dialysis adequacy.

Strengths of our study include the relatively large sample size, which is among the largest cohort of dialysis patients treated with remdesivir. In addition, our study population was racially/ethnically diverse from a single integrated health system that had comprehensive capture of health information. Furthermore, our study included both peritoneal and hemodialysis patients.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrated that remdesivir treatment in both peritoneal and hemodialysis patients hospitalized with COVID-19 was not associated with worsened transaminitis, ICU and mortality outcomes compared with patients who did not receive remdesivir. Furthermore, remdesivir-treated patients demonstrated a trend toward improvement in 30-day mortality.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Paul Saario, Noel Pascual and the KPSC Renal Business Group for their help and support with data acquisition and analysis.

Contributor Information

Kirollos E Zaki, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Cheng-Wei Huang, Department of Hospital Medicine, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, CA, USA.

Hui Zhou, Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, CA, USA; Department of Research and Evaluation Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, CA, USA.

Joanie Chung, Department of Research and Evaluation Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, CA, USA.

David C Selevan, Regional Quality and Clinical Analysis, Southern California Permanente Medical Group Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, CA, USA.

Mark P Rutkowski, Regional Quality and Clinical Analysis, Southern California Permanente Medical Group Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, CA, USA.

John J Sim, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, CA, USA.

FUNDING

This study was supported by Kaiser Permanente Southern California Regional Research and the Renal Business Group.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design was by K.E.Z., J.J.S. and H.Z. Acquisition and analysis of data was performed by D.C.S., J.C., M.P.R., H.Z., K.E.Z., J.J.S. and C.-W.H. Drafting and submission of the manuscript was done by K.E.Z., J.J.S. and C.H. Critical review and revision of manuscript was by H.Z., M.P.R., D.C.S. and J.C. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. Any additional data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

REFERENCES

- 1. Couchoud C, Bayer F, Ayav Cet al. Low incidence of SARS-CoV-2, risk factors of mortality and the course of illness in the French national cohort of dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2020;98:1519–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kazmi S, Alam A, Salman Bet al. Clinical course and outcome of ESRD patients on maintenance hemodialysis infected with COVID-19: a single-center study. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2021;14:193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sim JJ, Huang CW, Selevan DCet al. COVID-19 and survival in maintenance dialysis. Kidney Med 2021;3:132–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Valeri AM, Robbins-Juarez SY, Stevens JSet al. Presentation and outcomes of patients with ESKD and COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;31:1409–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xiong F, Tang H, Liu Let al. Clinical characteristics of and medical interventions for COVID-19 in hemodialysis patients in Wuhan, China. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;31:1387–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adamsick ML, Gandhi RG, Bidell MRet al. Remdesivir in patients with acute or chronic kidney disease and COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 31:1384–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LEet al. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19—final report. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1813–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes Ret al. Early remdesivir to prevent progression to severe Covid-19 in outpatients. N Engl J Med 2022;386:305–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rubin D, Chan-Tack K, Farley Jet al. FDA approval of remdesivir—a step in the right direction. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2598–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium, Pan H, Peto R, Henao-Restrepo AMet al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for COVID-19 – interim WHO SOLIDARITY trial results. N Engl J Med 2021;384:497–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Y, Zhang D, Du Get al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet North Am Ed 2020;395:1569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. FDA. Fact sheet for health care providers emergency use authorization (EUA) of remdesivir (GS-5734™). Food and Drug Administration 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jorgensen SCJ, Kebriaei R, Dresser LD. Remdesivir: review of pharmacology, pre-clinical data, and emerging clinical experience for COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy 2020;40:659–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MKet al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US census bureau data. Perm J 2012;16:37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DRet al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ng JH, Hirsch JS, Wanchoo Ret al. Outcomes of patients with end-stage kidney disease hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int 2020; 98:1530–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaka AS, MacDonald R, Greer Net al. Major update: remdesivir for adults with COVID-19: a living systematic review and meta-analysis for the American College of Physicians practice points. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:663–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilead Sciences Inc. Veklury (remdesivir) Prescribing Information . Published online2022. https://www.gilead.com/-/media/files/pdfs/medicines/covid-19/veklury/veklury_pi.pdf (15 March 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sörgel F, Malin JJ, Hagmann Het al. Pharmacokinetics of remdesivir in a COVID-19 patient with end-stage renal disease on intermittent haemodialysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021;76:825–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang CW, Desai PP, Wei KKet al. Characteristics of patients discharged and readmitted after COVID-19 hospitalisation within a large integrated health system in the United States. Infect Dis 2021;53:800–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. Any additional data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.