Abstract

Background

Adults over 50 have high health care needs but also face high coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related vulnerability. This may result in a reluctance to enter public spaces, including health care settings. Here, we examined factors associated with health care delays among adults over 50 early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Using data from the 2020 wave of the Health and Retirement Study (N = 7 615), we evaluated how race/ethnicity, age, geographic region, and pandemic-related factors were associated with health care delays.

Results

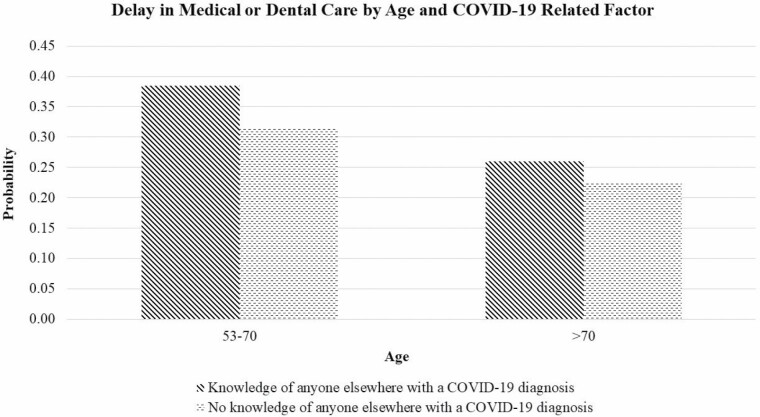

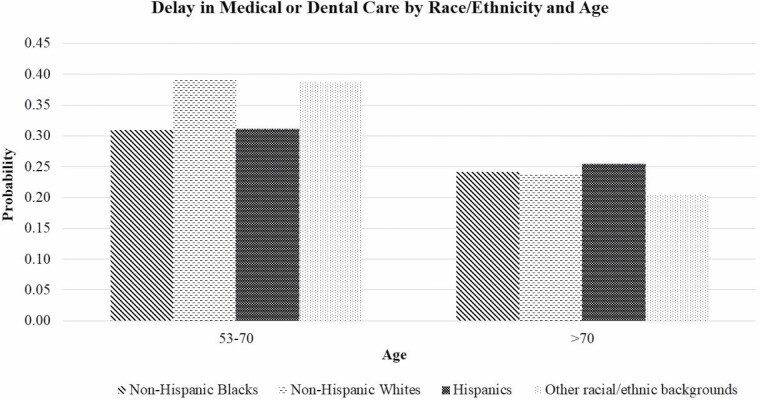

In our sample, 3 in 10 participants who were interviewed from March 2020 to June 2021 reported delays in medical or dental care in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Non-Hispanic Whites (odds ratio [OR]: 1.37; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.19–1.58) and those of other racial/ethnic backgrounds (OR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.02–1.67) delayed care more than Non-Hispanic Blacks. Other factors associated with delayed care included younger age, living in the Midwest or West, knowing someone diagnosed with or who died from COVID-19, and having high COVID-19-related concerns. There were no differences in care delays among adults aged > 70; however, among those ≤ 70, those who knew someone diagnosed with COVID-19 were more likely to delay care than those who did not. Additionally, among those ≤ 70, Non-Hispanic Whites and those of other racial/ethnic backgrounds delayed care more than Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics.

Conclusions

There is considerable heterogeneity in care delays among older adults based on age, race/ethnicity, and pandemic-related factors. As the pandemic continues, future studies should examine whether these patterns persist.

Keywords: Age, Coronavirus, Geographical region, Health and Retirement Study, Health care delay, Race/Ethnicity

In the early months of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the U.S. health care system experienced major interruptions, with temporary closures of medical clinics, cancellation of non-emergent surgeries, and a shift to telehealth services for routine care (1–3). Studies of the general adult population suggest that delays in seeking health care services have been common during the pandemic (1,4–8). Using data from the Current Population Survey collected in May 2020, Callison and Ward reported that 6% of Americans reported involuntary cancellations or delays in non-COVID-19 medical care (4). In another population-based study conducted in June 2020, Czeisler and colleagues reported that 41% of U.S. adults had voluntarily delayed or avoided care because of the COVID-19 pandemic (5).

Adults over 50 typically have a higher need for health care services than younger people, as they are disproportionately affected by chronic health conditions (9,10). At the same time, adults in this age group also face a greater risk of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality than their younger counterparts (11,12). To date, however, few studies have focused on adults over 50 (13–17), as most early pandemic studies of health care delays broadly focused on the general adult population (1,4–8). Understanding the factors associated with health care delays among older adults is crucial, as individuals in this age group could face disastrous consequences due to reduced contact with the health care system. The purpose of the current study was to identify factors associated with delayed care among U.S. community-dwelling adults over 50.

We hypothesized that there would be racial/ethnic differences in health care delays in this population. There are longstanding ethnic/racial disparities in health and in health care avoidance/delays among adults in this population. In pre-pandemic studies of U.S. adults aged > 65 years, Non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, and adults of other racial/ethnic backgrounds were almost twice as likely to delay health care than their Non-Hispanic White counterparts (18,19). These delays were primarily attributable to limited health care access, being too busy to go to the doctor, stigma about going to the doctor, and mistrust in medical systems (20,21). In the early months of the pandemic, Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics were twice as likely as Non-Hispanic Whites to consider the COVID-19 outbreak to be a major threat to their personal health (22,23). Thus, these groups may have delayed care due to concerns about contracting COVID-19 in health care spaces. Nevertheless, an early pandemic study found that Non-Hispanic Whites aged over 50 were more likely to delay seeking medical care compared to Non-Hispanic Blacks (17).

We were also interested in geographic differences in care delays in this population. Early pandemic policies (eg, stay-at-home orders) varied greatly by geographical region. By March 30, 2020, 28 states had issued statewide stay-at-home orders (primarily in the West and the Northeast), while 14 states had issued orders only in certain parts of the state (24). From April to December 2020, physical distancing was least common in the South and the Midwest (25). Further, Western and Northeastern states were more likely to have Democratic governors than Midwestern and Southern states, and studies have shown that states with Democratic governors were significantly faster to adopt statewide stay-at-home orders than those with Republican governors (26). Moreover, pre-pandemic studies of older adults have demonstrated that older adults in the Midwest were more likely to delay doctors’ visits than those in the Northeast (24). Given these data, we were interested in whether there were differences in care delays based on geographic region.

Additionally, we were interested in whether age would be associated with care delays in this population. Age is positively associated with health care utilization, as older adults generally have more chronic health conditions that require active management than their younger counterparts (9,10). At the same time, age is also positively associated with vulnerability to COVID-19 (8,9). Older adults may have been reluctant to leave home for in-person appointments and/or less comfortable using technology to receive telehealth services. Given these 2 competing possibilities, we wanted to examine how age contributed to how adults over 50 delayed or forwent care (27)

Finally, we were interested in exploring how race/ethnicity and pandemic-related factors might moderate the association between age and care delays. We expected that younger Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics would be more likely to delay care than older Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics, as they would likely decide that the risks of contracting COVID-19 in public spaces would outweigh the risks associated with postponement of regular health care services. We expected that younger participants with more direct or indirect exposure to COVID-19 (ie, those who lived with or knew someone with COVID-19) would delay care more than those with low exposure to COVID-19 for similar reasons.

We addressed our research questions using data from the special 2020 COVID-19 module of Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a large-scale, population-based study of adults aged > 50. We examined whether race/ethnicity, age, geographical region, and pandemic-related factors were associated with health care delays in this population. We also explored how race/ethnicity and pandemic-related factors might moderate the association between age and delayed care.

Method

Data Source

Data were primarily drawn from the 2020 waves of the HRS, a biennial, longitudinal population-based study of U.S. community-dwelling adults aged 53 years or older in 2020. The HRS uses a multistage probability sampling design with clustering to identify household units as the primary sampling unit. The details of the HRS study design and sample procedures are reported elsewhere (28). Of note, the study oversampled Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic populations in each incoming cohort to achieve adequate sample sizes to support subgroup comparisons by race/ethnicity (28). At each wave, participants completed an interview that included an assessment of demographic characteristics, health status, health insurance, and utilization of health resources. In the 2020 wave, the public use data of the HRS were expanded to include a module on COVID-19, in which data were collected via telephone or web-based survey between March 2020 and June 2021 (Supplement Table 2).

In the 2020 HRS wave, 9 751 participants answered questions about health care delays. We excluded 2 136 participants who had missing data on key demographic variables (n = 110), work status and insurance coverage (n = 207), health and past health care utilization (n = 1 333), and pandemic-related variables (n = 486).

Our final sample included a total of 7 615 participants. Compared to those excluded from the sample, those included were more likely to be younger (p < .001), Non-Hispanic Whites (p < .001), and live in a Southern state (p = .019). Those included were also less likely to have COVID-19-related exposure (p < .05; Supplementary Table 1). The mean age of our final sample was 68.18 (SD 10.15; range 53–104). Our final sample was 56.0% Non-Hispanic White, 22.2% Non-Hispanic Black, 16.8% Hispanics, and 5.1% of other racial/ethnic backgrounds (Table 1). Overall, 59.7% of participants were female, 53.3% were married, and 55.1% had at least some college education. Approximately one-third (32.3%) were working currently, while 94.2% and 54.7% were covered by medical and dental insurance, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Total Sample (N = 7 615) |

Delayed Health

Care (n = 2 379) |

No Delayed Health Care (n = 5 236) |

p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes and Variables of Interest | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Delayed medical or dental care | 2 379 | (31.2) | |||||

| Variables of interest | |||||||

| Race/ethnicity | .133 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 1 688 | (22.2) | 520 | (21.9) | 1 168 | (22.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 4 261 | (56.0) | 1 339 | (56.3) | 2 922 | (55.8) | |

| Hispanics | 1 280 | (16.8) | 381 | (16.0) | 899 | (17.2) | |

| Other racial/ethnic background | 386 | (5.1) | 139 | (5.8) | 247 | (4.7) | |

| Age (Mean, SD) | 68.18 | (10.15) | 66.23 | (9.21) | 69.06 | (10.43) | <.001 |

| 53-70 | 4 886 | (64.2) | 1 730 | (72.7) | 3 156 | (60.3) | |

| >70 | 2 729 | (35.8) | 649 | (27.3) | 2 080 | (39.7) | |

| U.S. geographical region | .027 | ||||||

| Northeast | 1 095 | (14.4) | 349 | (14.7) | 746 | (14.2) | |

| Midwest | 1 523 | (20.0) | 496 | (20.8) | 1 027 | (19.6) | |

| South | 3 304 | (43.4) | 973 | (40.9) | 2 331 | (44.5) | |

| West | 1 693 | (22.2) | 561 | (23.6) | 1 132 | (21.6) | |

| Prior/current COVID-19 diagnosis | 315 | (4.1) | 104 | (4.4) | 211 | (4.0) | .488 |

| Knowledge of anyone in the household with a COVID-19 diagnosis | 282 | (3.7) | 83 | (3.5) | 199 | (3.8) | .504 |

| Knowledge of anyone elsewhere with a COVID-19 diagnosis | 3 765 | (49.4) | 1 354 | (56.9) | 2 411 | (46.0) | <.001 |

| Knowledge of anyone who had died of COVID-19 | 2 029 | (26.6) | 743 | (31.2) | 1 286 | (24.6) | <.001 |

| High concerns about COVID-19 pandemic | 5 132 | (67.4) | 1 693 | (71.2) | 3 439 | (65.7) | <.001 |

| Covariates | |||||||

| Marital status | <.001 | ||||||

| Married | 4 059 | (53.3) | 1 202 | (50.5) | 2 857 | (54.6) | |

| Never married | 641 | (8.4) | 208 | (8.7) | 433 | (8.3) | |

| Divorced/separated | 1 555 | (20.4) | 599 | (25.2) | 956 | (18.3) | |

| Widowed | 1 360 | (17.9) | 370 | (15.6) | 990 | (18.9) | |

| Female | 4 543 | (59.7) | 1 559 | (65.5) | 2 984 | (57.0) | <.001 |

| Education | |||||||

| Some high school | 1 084 | (14.2) | 287 | (12.1) | 797 | (15.2) | <.001 |

| High school graduate | 1 928 | (25.3) | 516 | (21.7) | 1 412 | (27.0) | |

| General Educational Development (GED) test | 412 | (5.4) | 110 | (4.6) | 304 | (5.8) | |

| Some college | 2 129 | (28.0) | 720 | (30.3) | 1 409 | (26.9) | |

| Completed college or above | 2 062 | (27.1) | 746 | (31.4) | 1 316 | (25.1) | |

| Employment status | <.001 | ||||||

| Working currently | 2 462 | (32.3) | 802 | (33.7) | 1 660 | (31.7) | |

| Unemployed | 221 | (2.9) | 92 | (3.9) | 129 | (2.5) | |

| Temporarily laid off | 194 | (2.5) | 66 | (2.8) | 128 | (2.4) | |

| Disabled or on sick leave | 892 | (11.6) | 353 | (14.8) | 529 | (10.1) | |

| Retired | 3 394 | (44.6) | 927 | (39.0) | 2 467 | (47.1) | |

| Homemaker | 366 | (4.8) | 113 | (4.7) | 253 | (4.8) | |

| Other | 96 | (1.3) | 26 | (1.1) | 70 | (1.3) | |

| Medical insurance status | 7 170 | (94.2) | 2 232 | (93.8) | 4 938 | (94.3) | .400 |

| Dental insurance status | 4 166 | (54.7) | 1 418 | (59.6) | 2 748 | (52.5) | <.001 |

| History of chronic health conditions | 5 720 | (75.1) | 1 797 | (75.5) | 3 923 | (74.9) | .567 |

| Current use of medications or medical treatment | 4 901 | (64.4) | 1 526 | (64.1) | 3 375 | (64.5) | .792 |

| Poor/fair perceived health | 2 202 | (28.9) | 796 | (33.5) | 1 406 | (26.9) | <.001 |

| More than 5 times medical visits in 2016–2018 | 3 632 | (47.7) | 1 257 | (52.8) | 2 375 | (45.4) | <.001 |

Study Variables

Assessment of care delays

Participants were asked whether they had delayed medical care (eg, having surgery, seeing the doctor, filling prescriptions, and dental care) since March 2020. If yes, participants were asked to choose the reasons for health care delays (eg, could not afford it; could not get an appointment; the clinic, hospital, doctor’s office canceled, closed or suggested rescheduling; decided it could wait; and was afraid to go). Of note, telemedicine visits during this period were not considered delays in health care.

Assessment of age, race/ethnicity, and geographic region

Data on age (continuous measure) and race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other racial/ethnic background) were obtained via self-report. State-level geographic information for HRS participants was obtained from the HRS-restricted data files via a special agreement between the study investigators and the HRS project (29). Data for participants’ state of residence were categorized into 4 U.S. regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau (30).

COVID-19-related factors

Participants were asked the following questions: “Have you had or do you now have COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus?” (yes/no), “Has anyone in your household other than you been diagnosed with COVID-19?” (yes/no), “Has anyone else you know been diagnosed with COVID-19?” (yes/no), “Has anyone you know died from COVID-19?” (yes/no), and “How concerned are you about the coronavirus pandemic?” (10-point Likert scale from 1 “least concerned” to 10 “most concerned”). For COVID-19 concerns, we categorized those with responses above the mean (mean = 7.8) as having “high concern” and those with responses below the mean as having “low concern.”

Covariates

Our analyses controlled for self-reported marital status (married, never married, divorced/separated, or widowed), sex (male or female), education (some high school, high school graduate, General Educational Development (GED) test, some college, college or above), employment status (working currently, unemployed, temporarily laid off, disabled or on sick leave, retired, and homemaker), medical insurance status (insured: yes/no), dental insurance status (insured: yes/no), current use of medications or medical treatment (yes/no), and self-rated health (poor/fair or excellent/very good/good), and history of chronic health conditions (yes/no) and pre-pandemic health service utilization. With respect to chronic health conditions, we evaluated the prevalence of 5 conditions known to increase the risk of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality (31): hypertension, diabetes, chronic lung disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke. To assess pre-pandemic health service utilization, we used data from the 2018 HRS wave to determine if participants had high pre-pandemic health service utilization in the previous 2 years, (defined as more than 5 times medical visits in the previous 2 years (yes/no)).

Statistical Analyses

We used logistic regression to assess associations between our variables of interest (age, race/ethnicity, geographical region, and pandemic-related factors) and health care delays, adjusting for our covariates. All categorical variables were dummy coded. We calculated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) to evaluate associations between our variables of interest and health care delays. All analyses were completed using SPSS version 28 (Chicago, IL). Results were considered statistically significant if p-values were less than .05. To examine interactions between age and our potential moderators with respect to health care delays, we used first-order cross-product terms for age (continuous measure) and our proposed moderator variables. Interaction terms were entered into the regression equation with the corresponding main effects and covariates.

Results

Delays in Medical/Dental Care for Adults over 50

About 3 in 10 participants in our sample (31.2%) reported delays in medical or dental care (Table 1). While some participants reported delays in multiple medical needs, the most common health care delays were in getting dental care (22.8%) and seeing a doctor (17.9%), followed by delays in having surgery (4.0%) and filling prescriptions (2.1%). Of those reporting delays, the top 3 reasons for delay were the canceling, closure, or rescheduling of the doctor’s office (52.9%), deciding that the condition could wait (34.3%), and being afraid to go (24.0%).

Factors Associated With Health Care Delays

We observed that younger age was associated with increased odds of care delays. Adults aged 53–70 (OR: 1.67; 95% CI: 1.46–1.92) were more likely to delay health care than adults aged > 70 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Model for Association Between Variables of Interest and Delays in Care

| Full Sample | ||

|---|---|---|

| (N = 7 615) | ||

| Factors associated with Delays in Care+ | OR* | (95% CI) |

| Race/ethnicity (Ref. = Non-Hispanic Blacks) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 1.37 | (1.19, 1.58) |

| Hispanics | 1.09 | (0.91, 1.30) |

| Other racial/ethnic backgrounds | 1.31 | (1.02, 1.67) |

| Age (Ref. = 71–104) | ||

| 53–70 | 1.67 | (1.46, 1.92) |

| U.S. geographical region (Ref. = South) | ||

| Northeast | 1.06 | (0.91, 1.23) |

| Midwest | 1.19 | (1.04, 1.37) |

| West | 1.22 | (1.06, 1.40) |

| Prior/current COVID-19 diagnosis | 1.00 | (0.76, 1.31) |

| Knowledge of anyone in the household with a COVID-19 diagnosis | 0.85 | (0.63, 1.14) |

| Knowledge of anyone elsewhere with a COVID-19 diagnosis | 1.34 | (1.20 1.50) |

| Knowledge of anyone who had died of COVID-19 | 1.16 | (1.03, 1.32) |

| High concerns about COVID-19 pandemic | 1.26 | (1.13, 1.41) |

Statistically significant odd ratios at the 5% are bolded.

Notes: *CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; ref. = reference.

†Only variables of interest are shown in the table (ie, race/ethnicity, age, and COVID-19-related factors). The logistic regression model was adjusted for covariates, including marital status, sex, education, employment status, medical and dental insurance status, history of chronic health conditions, current use of medications or medical treatment, poor/fair perceived health, and past health service utilization.

We also evaluated associations between race/ethnicity and delayed care. Non-Hispanic Whites (OR: 1.37; 95% CI: 1.19–1.58) and those of other racial/ethnic backgrounds (OR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.02–1.67) were more likely to delay health care than Non-Hispanic Blacks. However, we observed no significant differences in health care delays between Hispanics and Non-Hispanic Blacks (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.91–1.30).

Additionally, we evaluated how the geographic region was associated with delays in care. We observed that those living in the Midwest (OR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.04–1.37) and the West (OR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.06–1.40) were more likely to delay health care than those living in the South. However, we observed no significant differences in health care delays between those living in the Northeast and the South (OR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.91–1.23).

Finally, we evaluated how pandemic-related concerns might be associated with health care delays. We observed that individuals reporting high COVID-19 concerns were more likely to delay care than those with low concerns (OR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.13–1.41). Those who knew someone diagnosed with COVID-19 (OR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.20–1.50) or knew someone who died from COVID-19 (OR: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.03–1.32) were more likely to delay care than their counterparts.

Potential Moderators

We were interested in how pandemic-related factors might moderate the association between age and health care delays. We observed a significant interaction effect between knowing anyone diagnosed with COVID-19 and age with respect to health care delays (β = −0.042; p = .001). Among those ages 53–70, those who knew anyone diagnosed with COVID-19 were more likely to delay care than those who did not (p < .001; η 2 = .005; Figure 1). Among those aged > 70 years, however, there was no association between knowing someone diagnosed with COVID-19 and care delays (p = .054; η 2 = .001). None of the other pandemic-related factors (eg, self-diagnosed with COVID-19, knowing any household members diagnosed with COVID-19, knowing someone who died of COVID-19, and level of COVID-19 concern) interacted with age with respect to health care delays.

Figure 1.

Probability of delay in medical or dental care by age and COVID-19 related factor. Note: The model adjusted for marital status, sex, education, employment status, medical and dental insurance status, history of chronic health conditions, current use of medications or medical treatment, poor/fair perceived health, past health service utilization, geographic region, and COVID-19 related factors.

Finally, we were interested in how race/ethnicity might moderate the association between age and health care delays. We observed a significant interaction effect between race/ethnicity and age with respect to health care delays (p = .003). There were no racial/ethnic differences in care delays among those over 70 (p = .809; η 2 < .001; Figure 2). Among those ages 53–70, however, Non-Hispanic Whites and those of other racial/ethnic backgrounds were more likely to delay care than Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics (p < .001, η 2 = .007).

Figure 2.

Probability of delay in medical or dental care by age and race/ethnicity. Note: The model adjusted for marital status, sex, education, employment status, medical and dental insurance status, history of chronic health conditions, current use of medications or medical treatment, poor/fair perceived health, past health service utilization, geographic region, and COVID-19 related factors.

Sensitivity Analyses

Given that we excluded many individuals from our analyses for whom we did not have data on health care utilization behaviors in 2018, we conducted sensitivity analyses to determine if our results were consistent without excluding these individuals. We observed that our findings persisted even without these exclusion criteria.

Discussion

In our sample, 3 in 10 participants who were interviewed from March 2020 to June 2021 reported delays in medical or dental care. Our findings demonstrated that younger age (53–70), living in the Midwest and West (vs South), knowing anyone diagnosed with COVID-19, knowing anyone who died from COVID-19, and high concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with greater odds of health care delays. Additionally, Non-Hispanic Whites and those of other racial/ethnic backgrounds were more likely to delay care than Non-Hispanic Blacks.

Younger age may have been associated with greater care delays for several reasons. First, adults ages 53–70 may generally focus less attention on illness and health management support from others. Frankel’s framework of aging (32) describes 5 distinct stages of aging: independence, interdependence, dependency, and crisis management. According to this framework, those in late midlife tend to focus their attention on independence and self-sufficiency, choosing to manage their health problems without special care or support. As people get older and chronic health conditions worsen, they begin to engage more deliberately with the health care system to manage their health concerns. Second, those ages 53–70 tend to manage more social roles than their older counterparts, including the roles of employee, parent, and caregiver for older adult parents (33). The demands of these roles were likely exacerbated during the early phase of the pandemic, which may have distracted these individuals from self-management of their health.

Despite our observation that younger age was associated with more care delays, the relationship between these 2 variables was not consistent. Younger participants who did not know someone diagnosed with COVID-19 and those of Non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic ethnicity delayed care at levels similar to older participants. It is possible that these participants had less perceived risk of COVID-19 than their counterparts; thus, they were less likely to postpone care in order to mitigate this risk. Those who knew someone diagnosed with COVID-19 might have had more firsthand knowledge of the potential health impacts of COVID-19, thus contributing to their perceived risk. These potential differences in perceived risk may have discouraged continued engagement with the health care system. However, it is less than clear why younger Non-Hispanic Whites were more likely to delay care compared to younger Non-Hispanic Blacks. The interaction findings between race/ethnicity and age were contradictory to our hypothesis because Non-Hispanic Blacks have been more likely to be hospitalized and die from COVID-19 than Non-Hispanic Whites from the early months of the pandemic (34–36). Nevertheless, we speculate that it is possible that the racial/ethnic disparities in health care delays change over the course of the pandemic. Ahmed and colleagues found that Non-Hispanic White adults were most likely to delay care at the start of the pandemic; however, Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics became the most likely to delay care as the pandemic persisted due to financial strain and loss of insurance coverage (37). As a majority of our samples were covered by medical insurance, future studies should explore this finding further to more clearly elucidate racial/ethnic disparities in health care delays among adults over 50.

In our sample, there were also geographic differences in care delays, with those living in Midwestern and Western states more likely to delay care than those in the South, and no difference in care delays between Northeastern and Southern states. This finding is unexpected, as we anticipated that geographical differences in care delays would largely be related to regional differences in stay-at-home orders and physical distancing. In the early stages of the pandemic, Zang and colleagues observed that rates of physical distancing were highest in Northeastern and Western states (25). Thus, we would have expected more delays in these regions. We call for future studies to further illuminate geographic disparities in care delays.

This study is not without limitations. While the HRS uses a population-based sample, it oversamples based on race/ethnicity; thus, survey weights are needed to ensure that the sample is nationally representative. At the time of our analyses, survey weights were not yet available for the 2020 wave. Thus, our estimates do not reflect population estimates. Additionally, we acknowledge that a failure to report health care delays may reflect less perceived medical need rather than actual health care delays. We attempted to account for perceived medical need by controlling for health care utilization in the 2 years prior to our study; however, it is possible that this did not effectively capture perceived need. Further, our data were collected over a 15-month period during the early stage of the pandemic (from March 2020 to June 2021). There may have been differences in care-seeking between those who participated in the HRS during the early versus later stages of the pandemic. Moreover, delays in health care described here may not have continued in subsequent stages of the pandemic, especially as more health care facilities revised their policies related to facility access. Follow-up data collected later in the pandemic period is needed to elucidate whether these patterns of health care delays persist over the entire period (37). Finally, our data did not address some important reasons for pandemic-related health care delays, such as mistrust of the health care system, reduced availability of public transportation, and adherence to public health recommendations. Qualitative research may more clearly illuminate additional reasons for delay in medical care.

Despite these limitations, our study has important implications. This is one of the few studies that examine the factors associated with health care delays among adults over 50 during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings suggest that Non-Hispanic Whites, those 53–70 years of age, those living in the Midwest and the West, those knowing anyone diagnosed with or who died from COVID-19, and those with high COVID-19 concerns may have delayed health care in the early stage of the pandemic, such that re-engagement with these groups is necessary. As the pandemic continues, future studies should continue to evaluate factors associated with health care delays in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This analysis uses data from the Health and Retirement Study, (2018 and 2020 HRS Core Files, RAND HRS Longitudinal File, and Cross-Wave Geographic Information—State Restricted Data File), sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and conducted by the University of Michigan.

Contributor Information

Athena C Y Chan, Department of Family Social Science, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA.

Rodlescia S Sneed, Institute of Gerontology and Department of Psychology, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG015281).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Anderson KE, McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Barry CL. Reports of forgone medical care among US adults during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open 2021;4(1):e2034882. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chudasama YV, Gillies CL, Zaccardi F, et al. . Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: a global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab Synd. 2020;14(5):965–967. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sarac NJ, Sarac BA, Schoenbrunner AR, et al. . A review of state guidelines for elective orthopaedic procedures during the COVID-19 outbreak. JBJS. 2020;102(11):942–945. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.20.00510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Callison K, Ward J. Associations between individual demographic characteristics and involuntary health care delays as a result of COVID-19. Health Affairs 2021;40(5):837–843. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Czeisler ME, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. . Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns—United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250–1257. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giannouchos TV, Brooks JM, Andreyeva E, Ukert B. Frequency and factors associated with foregone and delayed medical care due to COVID-19 among nonelderly US adults from August to December 2020. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28(1):33–42. doi: 10.1111/jep.13645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gonzalez D, Karpman M, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S.. Delayed and Forgone Health Care for Nonelderly Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. 2021. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/delayed-and-forgone-health-care-nonelderly-adults-during-covid-19-pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kranz AM, Gahlon G, Dick AW, Stein BD. Characteristics of US adults delaying dental care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2021;6(1):8–14. doi: 10.1177/2380084420962778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ahn S, Hussein M, Mahmood A, Smith ML. Emergency department and inpatient utilization among U.S. older adults with multiple chronic conditions: a post-reform update. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4902-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M.. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. RAND Corporation. 2017. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL221.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11. López-Bueno R, Torres-Castro R, Koyanagi A, Smith L, Soysal P, Calatayud J. Associations between recently diagnosed conditions and hospitalization due to COVID-19 in patients aged 50 years and older-A SHARE-based analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77(4):e111–e114. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glab199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lopez L, III, HartLH, III, Katz MH. Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA 2021;325(8):719–720. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Das AK, Mishra DK, Gopalan SS. Reduced access to care among older American adults during COVID-19 pandemic: results from a prospective cohort study. J Clin Images Med Case Rep. 2021;2(4):1240. doi: 10.52768/2766-7820/1240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lei L, Maust DT. Delayed care related to COVID-19 in a nationally representative sample of older Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1337–1340. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07417-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lu P, Kong D, Shelley M. Risk perception, preventive behavior, and medical care avoidance among American older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):577–584. doi: 10.1177/08982643211002084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Na L. Characteristics of community-dwelling older individuals who delayed care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;101:104710. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2022.104710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhong S, Huisingh-Scheetz M, Huang ES. Delayed medical care and its perceived health impact among US older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(6):1620–1628. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Song J, Chang RW. Gender and ethnic/racial disparities in health care utilization among older adults. J Gerontol B. 2002;57(4):S221–S233. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.S221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Towne. SD.Jr Socioeconomic, geospatial, and geopolitical disparities in access to health care in the US 2011–2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(6):573. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taber JM, Leyva B, Persoskie A. Why do people avoid medical care? a qualitative study using national data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):290–297. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3089-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun JK, Smith J. Self-perceptions of aging and perceived barriers to care: reasons for health care delay. Gerontologist. 2017;57(suppl_2):S216–S226. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park J. Who is hardest hit by a pandemic? Racial disparities in COVID-19 hardship in the U.S. Int J Urban Sci. 2021;25(2):149–177. doi: 10.1080/12265934.2021.1877566 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pew Research Center. U.S. Public Sees Multiple Threats From the Coronavirus – and Concerns Are Growing. March 18, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/03/18/u-s-public-sees-multiple-threats-from-the-coronavirus-and-concerns-are-growing/#racial-ethnic-differences-in-personal-health-concerns-from-coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baccini L, Brodeur A. Explaining Governors’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Am Polit Res. 2020;49(2):215–220. doi: 10.1177/1532673x20973453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zang E, West J, Kim N, Pao C. U.S. regional differences in physical distancing: Evaluating racial and socioeconomic divides during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0259665–e0259665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee JC, Hasnain-Wynia R, Lau DT. Delay in seeing a doctor due to cost: disparity between older adults with and without disabilities in the United States. Health Serv Res Apr 2012;47(2):698–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01346.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hacker KA, Briss PA, Richardson L, Wright J, Petersen R. COVID-19 and chronic disease: the impact now and in the future. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E62. doi: 10.5888/pcd18.210086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heeringa SG, Connor J. Technical description of the health and retirement study sample design.1995. Accessed February 1, 2021. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu.ezp1.lib.umn.edu/sitedocs/userg/HRSSAMP.pdf.

- 29. Health and retreatment study: available restricted data products. 2020. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/data-products/restricted-data/available-products. [Google Scholar]

- 30. United States Census Bureau. Guidance for economic census geographies users. 2021. Accessed May 1, 2022. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/economic-census/guidance-geographies/levels.html. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. . Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marak C. Understanding the 5 stages of aging from self-sufficiency to end of life. 2016. Accessed July 1, 2021. https://www.advisorpedia.com/viewpoints/understanding-the-5-stages-of-aging-from-self-sufficiency-to-end-of-life/. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D, Lachman ME. Midlife in the 2020s: opportunities and challenges. Am Psychol. 2020;75(4):470–485. doi: 10.1037/amp0000591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elo IT, Luck A, Stokes AC, Hempstead K, Xie W, Preston SH. Evaluation of age patterns of COVID-19 mortality by race and ethnicity from March 2020 to October 2021 in the US. JAMA Network Open 2022;5(5):e2212686–e2212686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.12686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Golestaneh L, Neugarten J, Fisher M, et al. . The association of race and COVID-19 mortality. EClinicalMedicine 2020;25:100455. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tirupathi R, Muradova V, Shekhar R, Salim SA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Palabindala V. COVID-19 disparity among racial and ethnic minorities in the US: a cross sectional analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;38:101904–101904. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahmed A, Song Y, Wadhera RK. Racial/ethnic disparities in delaying or not receiving medical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1341–1343. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07406-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.