Abstract

Introduction

Peritonsillar abscess is the most common deep neck infection. The infectious microorganism may be different according to clinical factors.

Objective

To identify the major causative pathogen of peritonsillar abscess and investigate the relationship between the causative pathogen, host clinical factors, and hospitalization duration.

Methods

This retrospective study included 415 hospitalized patients diagnosed with peritonsillar abscess who were admitted to a tertiary medical center from June 1990 to June 2013. We collected data by chart review and analyzed variables such as demographic characteristics, underlying systemic disease, smoking, alcoholism, betel nut chewing, bacteriology, and hospitalization duration.

Results

A total of 168 patients had positive results for pathogen isolation. Streptococcus viridans (28.57%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (23.21%) were the most common microorganisms identified through pus culturing. The isolation rate of anaerobes increased to 49.35% in the recent 6 years (p = 0.048). Common anaerobes were Prevotella and Fusobacterium spp. The identification of K. pneumoniae increased among elderly patients (age > 65 years) with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.76 (p = 0.03), and decreased in the hot season (mean temperature > 26 °C) (OR = 0.49, p = 0.04). No specific microorganism was associated with prolonged hospital stay.

Conclusion

The most common pathogen identified through pus culturing was S. viridans, followed by K. pneumoniae. The identification of anaerobes was shown to increase in recent years. The antibiotics initially selected should be effective against both aerobes and anaerobes. Bacterial identification may be associated with host clinical factors and environmental factors.

Keywords: Anaerobic bacteria, Bacterial infections, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Peritonsillar abscess, Viridans streptococci

Resumo

Introdução

O Abscesso Peritonsilar é a infecção cervical profunda mais comum. O microrganismo infeccioso pode ser diferente de acordo com os fatores clínicos.

Objetivo

Identificar o principal agente causador do abscesso peritonsilar e investigar a relação entre o patógeno causador, os fatores clínicos do hospedeiro e a duração da hospitalização.

Método

Este estudo retrospectivo incluiu 415 pacientes hospitalizados diagnosticados com abscesso peritonsilar que foram internados em um centro médico terciário de junho de 1990 a junho de 2013. Coletamos dados através da análise dos arquivos médicos dos pacientes e analisamos variáveis como características demográficas, doença sistêmica subjacente, tabagismo, alcoolismo, hábito de mascar noz de betel, bacteriologia e duração da hospitalização.

Resultados

Um total de 168 pacientes apresentaram resultados positivos para isolamento de patógenos. Streptococcus viridans (28,57%) e Klebsiella pneumoniae (23,21%) foram os microrganismos mais comuns identificados pela cultura da secreção. A taxa de isolamento de anaeróbios aumentou para 49,35% nos últimos 6 anos (p = 0,048). Os anaeróbios comuns foram Prevotella e Fusobacterium spp. A identificação de K. pneumoniae aumentou em pacientes idosos (idade > 65 anos) com razão de chances (Odds Ratio - OR) de 2,76 (p = 0,03) e diminuiu na estação do calor (temperatura média > 26 °C) (OR = 0,49, p = 0,04). Nenhum microrganismo específico foi associado à hospitalização prolongada.

Conclusão

O patógeno mais comumente identificado através da cultura de secreção foi S. viridans, seguido por K. pneumoniae. A identificação de anaeróbios mostrou ter aumentado nos últimos anos. Os antibióticos selecionados inicialmente devem ser efetivos contra aeróbios e anaeróbios. A identificação bacteriana pode estar associada a fatores clínicos e fatores ambientais do hospedeiro.

Palavras-chave: Bactérias anaeróbicas, Infecções bacterianas, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Abscesso peritonsilar, Viridans streptococci

Introduction

Peritonsillar abscess (PTA), or quinsy, is the most common deep neck infection.1 The abscess may spread into the parapharyngeal space of other deep neck spaces, to the adjacent structure, and to the bloodstream. It rarely occurs but PTA is potentially life threatening. Early diagnosis of PTA is extremely crucial, and appropriate antibiotics and surgical intervention to remove the abscess are required.2 Antibiotics result in a substantial reduction in the progression of this disease. The empirical antibiotic used should be effective against the possible causative pathogen of PTA.

Our objectives were to investigate the microbiology of PTA and to identify its relationship with clinical variables including the underlying systemic disease of patients; habits such as smoking, alcoholism, and betel nut chewing; and hospitalization duration.

Methods

Study design and sample population

This retrospective study included 415 patients with PTA who were admitted to a tertiary medical center located in Southern Taiwan from June 1990 to June 2013. Inclusion criteria were hospitalized patients who were clinically diagnosed with PTA (ICD-9 code 475) by positive pus aspiration or computed tomography (CT) imaging. We reviewed the chart of each patient to collect the following data: admission date, age, sex, height, weight, host clinical factors (diabetes mellitus [DM], hypertension, smoking habit, alcoholism, and betel nut chewing), pus culture result, antibiotic treatment, surgery, and hospitalization duration. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

We classified the bacteria into different categories according to the characteristics of Gram staining and anaerobic properties. We defined prolonged hospitalization as hospitalization duration of more than 6 days. Obesity was defined as a body mass index of more than 27, and elderly patients were defined as those aged older than 65 years. We defined the hot season as the months from May to October when the average temperature in Southern Taiwan was above 26 °C according to the record of the Central Weather Bureau of R.O.C.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), except for the Cochran–Armitage test, which was performed using the SAS program (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The association with each independent variable was statistically analyzed among the different groups. Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson's Chi-square test or the Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Trends of isolated pathogens were analyzed using the Cochran–Armitage test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethic statement

This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board; the approval protocol number is VGHKS14-CT7-01.

Results

Demographraphic characteristics

This study included 415 patients. The results of pus cultures from either surgery or needle aspiration were available for 266 patients. Adjustments for sample submitted to tonsil surgery or PTA drainage was performed, as shown in Table 1. There is no patient with history of AIDS or HIV infection in this study.

Table 1.

Demographraphic characteristics of patients with peritonsillar abscess.

| Age | Overall, (n = 266) | Diabetes mellitus | Smoking | Alcoholism | Betel-nut chewing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <18 y/o | 22 (8.27) | 0 | 6 (27.27) | 5 (22.73) | 2 (9.09) |

| 18–64 y/o | 215 (80.83) | 19 (8.84) | 111 (51.63) | 76 (35.35) | 37 (17.21) |

| ≥65 y/o | 29 (10.90) | 4 (13.79) | 5 (17.24) | 7 (24.14) | 3 (10.34) |

| Total | 266 (100) | 23 (8.65) | 122 (45.86) | 88 (33.08) | 42 (15.79) |

Data are presented as n (%).

y/o indicates “year old”.

Bacteriology

Within these patients with pus obtained, 230 (230–266, 86.47%) showed bacterial growth in their pus culture. The pus culture of the remaining 36 patients showed no bacterial growth. Of the 230 patients, 132 (132–230, 57.39%) had polymicrobial pus, including 62 cases merely reported as “normal flora” or “mixed flora” (62–230, 26.96%). Pus cultures of 168 patients (168–266, 63.15%) showed positive results for pathogen isolation. More than a single pathogen was isolated in 64 patients (64–168, 38.10%). Aerobic bacteria were isolated from 85.7% (144/168) of positive cultures, anaerobic or facultative aerobic bacteria from 44.0% (74–168), and mixed aerobic and anaerobic bacteria from 29.8% (50–168).

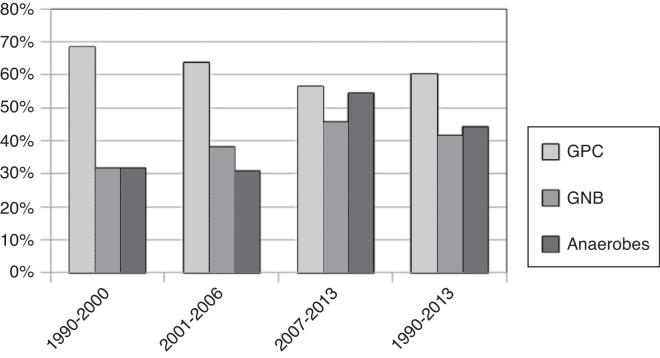

The most common pathogen identified through pus culturing was Streptococcus viridans (48–168, 28.57%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (39–168, 23.21%) and the beta-hemolytic Streptococcus group (17–168, 10.12%), as shown in Table 2. We divided patients by the 4 periods of 1990–1995, 1996–2001, 2002–2007, and 2008–2013; the isolation rate of the anaerobes was 25%, 23.81%, 45.45%, and 49.35%, respectively. The isolation rate of anaerobic pathogens increased significantly between 1990 and 2013 (Cochran–Armitage test, p = 0.048), as shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1. The isolation rates of gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria in these 4 periods were 100% and 25%, 57.14% and 47.62%, 62.12% and 48.48%, and 51.95% and 49.35%, respectively. Most of the anaerobic pathogens were Prevotella spp. (24–168, 14.29%) and Fusobacterium spp. (16–168, 9.52%), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bacteriology of 168 patients with peritonsillar abscess with definite isolation of pus culture.

| Causative pathogen | Overall (n = 168) | DM (n = 17) | HTN (n = 22) | Smoking (n = 78) | Alcoholism (n = 59) | Betel-Nut chewing (n = 27) | Obesity (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic GNB | 51 (30.36) | 10 (58.82) | 8 (36.36) | 22 (28.21) | 15 (25.42) | 8 (29.63) | 8 (26.67) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 39 (23.21) | 7 (41.18) | 7 (31.82) | 19 (24.36) | 13 (22.03) | 7 (25.93) | 7 (23.33) |

| Aerobic GPB | 22 (13.10) | 10 (58.82) | 5 (22.73) | 12 (15.38) | 11 (18.64) | 4 (14.81) | 6 (20.00) |

| Aerobic GNC | 4 (2.38) | 1 (5.88) | 1 (4.55) | 1 (1.28) | 1 (1.69) | 1 (3.70) | 2 (6.67) |

| Aerobic GPC | 99 (58.93) | 10 (58.82) | 12 (54.55) | 46 (58.97) | 32 (61.02) | 21 (77.78) | 19 (63.33) |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 9 (5.36) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (4.55) | 5 (4.6) | 5 (8.47) | 1 (3.70) | 2 (6.67) |

| Beta-hemolytic streptococcus group | 18 (10.71) | 1 (5.88) | 1 (4.55) | 15 (19.23) | 10 (16.95) | 4 (14.81) | 4 (13.33) |

| Streptococcus melliri group | 24 (14.29) | 4 (23.53) | 4 (18.18) | 10 (12.82) | 8 (13.56) | 9 (33.33) | 4 (13.33) |

| Streptococcus viridans group | 48 (28.57) | 5 (29.41) | 7 (31.82) | 16 (20.51) | 13 (22.03) | 7 (25.93) | 7 (23.33) |

| Anaerobic cocci | 34 (20.23) | 5 (29.41) | 5 (22.73) | 17 (21.79) | 13 (22.03) | 7 (25.93) | 11 (36.67) |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. | 9 (5.36) | 1 (5.88) | 1 (4.55) | 7 (8.97) | 6 (10.17) | 3 (11.11) | 4 (13.33) |

| Anaerobic GPB | 14 (8.33) | 1 (5.88) | 5 (22.73) | 5 (6.41) | 4 (6.78) | 2 (7.41) | 3 (10.00) |

| Anaerobic GNB | 45 (26.79) | 1 (5.88) | 6 (27.27) | 24 (30.77) | 18 (30.51) | 7 (25.93) | 6 (20.00) |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 17 (10.12) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (4.55) | 10 (12.82) | 6 (10.17) | 3 (11.11) | 2 (6.67) |

| Prevotella spp. | 24 (14.29) | 1 (5.88) | 4 (18.18) | 11 (14.10) | 10 (16.95) | 4 (18.18) | 4 (13.33) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Aerobic isolates included aerobic and facultative anaerobic isolates.

DM, diabetes mellitus; GNB, gram-negative bacilli; GNC, gram-negative cocci; GPB, gram-positive bacilli; GPC, gram-positive cocci; HTN, hypertension.

Table 3.

Isolation rate of different types of bacteria during each 6 year interval, 1990–2013.

| Years, number of patient types (%) of bacteria | 1990–1995 | 1996–2001 | 2002–2007 | 2008–2013 | Total (1990–2013) | Test for trends (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram positive (% of total patient) | 4 (100) | 12 (57.14) | 41 (62.12) | 40 (51.95) | 97 (57.74) | 0.120 |

| Gram negative (% of total patient) | 1 (25) | 10 (47.62) | 32 (48.48) | 38 (49.35) | 81 (48.21) | 0.569 |

| Anaerobes (% of total patient) | 1 (25) | 5 (23.81) | 30 (45.45) | 38 (49.35) | 74 (44.05) | 0.048a |

| Patient | 4 | 21 | 66 | 77 | 168 |

Denotes for p-value less than 0.05.

Figure 1.

Isolation rate of different types of bacteria during each 6 year interval.

Host clinical factors were associated with several isolated pathogens. Betel nut chewing was associated with the isolation of gram-positive cocci (GPC) (OR = 2.67, p = 0.04). The association of bacterial isolation with smoking habit and alcoholism was not statistically significant. Elderly patients (age > 65 years) had higher K. pneumoniae isolation (OR = 2.76, p = 0.03). Obesity (BMI > 27) was associated with a higher isolation of Peptostreptococcus (OR = 4.19, p = 0.04), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Association between the predisposing factors and the pathogen.a

| Predisposing factors | Causative pathogen | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderb | KP | 2.76 | 1.10–6.93 | 0.03e |

| Obesityc | Peptostreptococcus | 4.19 | 0.98–17.88 | 0.04e |

| Hot seasond | GPB | 3.22 | 1.13–9.19 | 0.02e |

| KP | 0.49 | 0.23–1.01 | 0.04e | |

| Betel-Nut chewing | GPC | 2.67 | 1.02–7.02 | 0.04e |

No statistically difference was observed among bacterial isolates and smoking, alcoholism, and DM.

Elderly indicates patient's age was more than 65 years old.

Obesity indicates patient's body mass index was more than 27.

Hot season indicates the admission date was between May and October, during which time the average temperature in southern Taiwan was more than 27 °C.

Denotes for p-value less than 0.05.

CI, confidence interval; DM, diabetes mellitus; GPB, gram-positive bacilli; GPC, gram-positive cocci; HTN, hypertension; KP, Klebsiella pneumoniae; OR, odds ratio.

In addition, in the hot season, we found that the risk of isolating gram-positive bacilli (GPB) increased (OR = 3.22, p = 0.02), but that of K. pneumoniae isolation decreased (OR = 0.49, p = 0.04), as shown in Table 4. There was no specific microorganism associated with prolonged hospital stay.

Searching from the PubMed database, there were 30 studies involved in bacteriology of PTA during 1980–2016. The timeframes, the geographical locations and the predominant bacterial species identified in these studies were listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Studies involved in bacteriology of PTA during 1980–2016.

| Investigator | Country | Year | Positive culture | Predominant aerobes | Predominant anaerobes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brook et al. (1981)19 | U.S. | – | 16 | Gamma-hemolytic streptococci | Bacteroides sp. |

| Alpha-hemolytic streptococci | Anaerobic GPC | ||||

| Jokipii et al. (1988)8 | Finland | – | 42 | Group A streptococcus | Peptostreptococcus sp. |

| Streptococcus viridans group | Bacteroides sp. | ||||

| Brook et al. (1991)37 | U.S. | 1978–1985 | 34 | Staphylococcus aureus | Bacteroides sp. |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Peptostreptococcus sp. | ||||

| Snow et al. (1991)38 | UK | – | 55 | Beta hemolytic streptococci | – |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |||||

| Jousimies-Somer et al. (1993)20 | Finland | – | 122 | Streptococcus pyogenes | Fusobacterium necrophorum |

| Streptococcus milleri group | Prevotella melaninogenica | ||||

| Mitchelmore et al. (1995)9 | UK | 1982–1992 | 45 | Group A streptococcus | Peptostreptococcus sp. |

| Prevotella | |||||

| Muir et al. (1995)39 | New Zealand | 1990–1992 | 39 | Group A streptococcus | – |

| Prior et al. (1995)40 Cherukuri (2002) |

UK | – | 45 | – | – |

| USA | 1990–1999 | 82 | Streptococcus sp. | – | |

| Haemophilus sp. | |||||

| Matsuda et al. (2002)10 | Japan | 1988–1999 | 386 | Alpha-hemolytic streptococci | Anaerobic gram-negative rods |

| Neisseria sp. | Porphyromnas sp. | ||||

| Hanna et al. (2006)41 | Northern Ireland | 2001–2002 | 37 | Group A streptococci | Bacteroides sp. |

| Sakae et al. (2006)42 | Brazil | 2001 | 26 | Streptococcus viridans | Peptostreptococcus sp. |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Prevotella sp. | ||||

| Zagolski et al. (2007) | Poland | – | 12 | Streptococcus sp. | Bacteroides sp. |

| Megalamani et al. (2008) | India | 2003–2006 | 39 | Beta hemolytic streptococcus | – |

| Pseudomonas | |||||

| Sunnergren et al. (2008)7 | Sweden | 2000–2006 | 67 | Group A streptococcus | Bacteroides sp. |

| Klug et al. (2009)11 | Denmark | 2001–2006 | 405 | Group A streptococcus | Fusobacterium sp. |

| Groups C or G streptococci | |||||

| Gavriel et al. (2009)6 | Israel | 1996–2002 | 137 | Streptococcus pyogenes | Prevotella sp. |

| Streptococcus intermedius | Peptostreptococcus sp. | ||||

| Segal et al. (2009)4 | Israel | 2004–2007 | 64 | Group A streptococcus | – |

| Group C streptococcus | |||||

| Repanos et al. (2009)32 | UK | 1998–2005 | 107 | Streptococcal sp. | – |

| Rusan et al. (2009) | Denmark | 2001–2006 | 623 | Group A streptococcus | Fusobacterium sp. |

| Acharya et al. (2010)5 | Nepal | 2007–2008 | 18 | Streptococcus pyogenes | – |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |||||

| Marom et al. (2010)17 | Canada | 1998–2007 | 180 | Streptococcus viridans | – |

| Group A streptococcus | |||||

| Hidaka et al. (2011)43 | Japan | 2002–2007 | 65 | Streptococcus milleri group | Prevotella sp. |

| Other Streptococcus sp. | Peptostreptococcus sp. | ||||

| Klug et al. (2011)12 | Denmark | 2005–2009 | 36 | Streptococcus viridans | Prevotella sp. |

| Neisseria sp. | Fusobacterium sp. | ||||

| Love et al. (2011)13 | New Zealand | 2006–2008 | 147 | Group A streptococcus Other beta-hemolytic streptococci | Fusobacterium sp. |

| Albertz et al. (2012)16 | Chile | 2000–2012 | 112 | Streptococcus pyogenes | Bacteroides sp. |

| Other streptococci | Peptostreptococcus sp. | ||||

| Fusobacterium sp. | |||||

| Takenaka et al. (2012)3 | Japan | 2005–2009 | 50 | Streptococcus pyogenes | Anaerobic |

| Streptococcus | |||||

| Fusobacterium sp. | |||||

| Sowerby et al. (2013)14 | Canada | 2009–2010 | 42 | Group A streptococcus | – |

| Streptococcus anginosus | |||||

| Gavriel et al. (2015) | Israel | 1996–2003 | 132 | Streptococcus pyogenes | Prevotella sp. |

| Peptostreptococcus sp. | |||||

| Mazur et al. (2015)18 | Poland | 2003–2013 | 45 | Streptococcus viridans group | Fusobacterium sp. |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Prevotella sp. | ||||

| Plum et al. (2015)44 | USA | 2002–2012 | 69 | Streptococcus milleri in adults | – |

| β-hemolytic streptococcus in children | |||||

| Lepelletier et al. (2016)36 | French | 2009–2012 | 412 | Group A streptococci | Fusobacterium spp. |

| Tachibana et al. (2016)45 | Japan | 2008–213 | 100 | Streptococcus viridans | Fusobacterium sp. |

| Vaikjarv et al. (2016)46 | Estonia | 2011–2012 | 22 | Streptococcus sp. | Streptococcus spp. |

| Present study (2017) | Taiwan | 1990–2013 | 168 | Streptococcus Viridans | Prevotella sp. |

| Klebsiella Pneumoniae | Fusobacterium sp. |

–, indicates “not disclosed”.

Several broad-spectrum antibiotics such as penicillin or cefazolin combined with gentamycin (GM) and metronidazole, clindamycin plus GM, or augmentin along were used in our series. All these antibiotics were effective without any significant difference.

Discussion

In our study, the most common pathogen identified through pus culturing in patients with PTA was S. viridans, followed by K. pneumoniae; commonly isolated anaerobes in our study were Prevotella and Fusobacterium spp. We reviewed the bacteriology data from previous studies, as shown in Table 5. Most of the studies3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 have reported group A Streptococcus as the most common aerobic pathogen in PTA; some studies12, 17, 18 have reported that common aerobic pathogens were S. viridans, followed by group A β-hemolytic streptococci. The prevalence of K. pneumoniae has been rarely reported in previous studies. In previous studies, Fusobacterium nucleatum,3, 8, 11, 12, 15, 19, 20 Prevotella,3, 12, 19, 20, 21 Bacteroides,7, 8, 19 Peptostreptococcus,8, 9, 20 and anaerobic streptococcus12 were the most common anaerobic pathogens. The divergence of bacterial culture may be owing to different geographical location. With difference between diets and lifestyle, the bacterial flora within each people may be also different.

K. pneumoniae and Streptococcus spp. are common oral flora normally found in the mouth and are odontogenic pathogens of deep neck infection.22, 23, 24 The S. viridans group is the etiological agent of dental caries, pericoronitis, or, if introduced into the bloodstream, endocarditis. In Taiwan, K. pneumoniae has been linked to lung infection in aspiration patients or a liver abscess25 in immunocompromised patients or those with diabetes.26

Patients with old age27 or diabetes mellitus28 are considered to be immunocompromised and have more chance to get infection. DM and elder are also linked with more complications and higher mortality rate in deep neck infection.29, 30 Thus PTA patients with above characteristics often have longer hospital stay.30 We reported the microbiology of PTA in such immunocompromised patients. Patients with DM had no increased risk of isolating K. pneumoniae as the causative pathogen of PTA. By contrast, elderly patients with PTA in the current series had a higher risk of K. pneumoniae isolation.

A trend toward a higher isolation rate for anaerobes was observed during 2002–2013 (p = 0.048). Gavriel6 reported a significant increase in anaerobic growth during 1996–1999 and then a slow nonsignificant decline until 2002. Takenaka3 reported no change in the percentage of cases with anaerobic growth between 2 periods (2005–2007 and 2008–2009). Such a phenomenon might result from a real change in pathogens; the alteration of antibiotics used, or improved culture methods for anaerobic pathogens. In our series, no major alteration of antibiotics used or improvement of the culture methods was observed. Physicians should prescribe empirical antibiotics to cover anaerobes.

PTA is often a polymicrobial infection. Polymicrobial growth was observed in the pus cultures of 57.39% of patients. The rationale of using empirical antibiotics was to cover GPCs, GNBs, and respiratory anaerobes. If necessary, suitable antibiotics should be chosen on the basis of culture results. However, the management of most uncomplicated patients may not be affected by the culture result.31 Repanos et al.32 suggested that using broad-spectrum antibiotics such as cephalosporin or penicillin combined with metronidazole was effective. In our study, no significant difference was found among several combinations of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Smoking habit has been commonly observed in patients with PTA in several studies17, 18, 33, 34; these studies have reported smoking as a risk factor for PTA. Marom et al.17 reported a significantly higher incidence for S. viridans, other gram-positive cocci isolates, and anaerobes. In our study, no statistical significance was observed in the causative pathogen between smokers and nonsmokers with PTA, similar to the findings of the study by Klug.34

Betel nut chewing is a popular habit in Southeast Asia. To the best of our knowledge, no study has found an association between the bacteriology of PTA and betel nut chewing. In our series, this habit was associated with a higher risk of GPC as a pathogen. In the study by Ling et al.,35 it was associated with a likelihood of subgingival infection by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis.

In our study, elderly patients (older than 65 year-old) had a high risk of K. pneumoniae isolation. The study by Marom17 reported a significantly higher isolation rate for infection by GPC (mixed Streptococcus species) and gram-negative rods in older patients (40 year-old or older) than in younger patients.

The hot season increased the risk of GPB infection and reduced the risk of K. pneumoniae infection in patients with PTA in our current study. Our institute is located in a tropical region that has approximately six months (May to October) of hot weather, with a mean temperature of 27 °C. By contrast, Klug et al.15 from another institute located in a temperate zone reported a higher incidence of F. nucleatum infection during summer than during winter. It also reported Group A streptococcus was significantly more frequently identified from in the winter and spring. The study in French36 reported PTA caused by S. pyogenes or anaerobes were more prevalent in the winter and spring than summer. Such fluctuation in the microbiology of PTA might be weather related.

In our series, no specific microorganism was associated with the poor prognosis of PTA. This finding is considerably similar to the reports by Marom17 and Mazur.18

Our study has several limitations. Because we retrospectively collected data by chart review, data from the medical record might be lost during the early years. As we used several small populations of isolated pathogens, a larger sample size is necessary to determine the relationship between the isolated pathogen and the predisposing factors.

Conclusions

The most common causative pathogen of PTA was S. viridans, followed by K. pneumoniae. The isolation of anaerobes significantly increased in recent years. The common ones were Prevotella and Fusobacterium spp. Empirical antibiotics targeting both aerobes and anaerobes should be appropriate as treatment. Bacterial isolation may be associated with host clinical factors, environmental factors, and hospitalization duration.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Hsueh-Wen Chang (Department of Biological Sciences, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan) for his help in the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: Tsai Y-W, Liu Y-H, Su H-H. Bacteriology of peritonsillar abscess: the changing trend and predisposing factors. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;84:532–39.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial.

References

- 1.Galioto N.J. Peritonsillar abscess. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steyer T.E. Peritonsillar abscess: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takenaka Y., Takeda K., Yoshii T., Hashimoto M., Inohara H. Gram staining for the treatment of peritonsillar abscess. Int J Otolaryngol. 2012;2012:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2012/464973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal N., El-Saied S., Puterman M. Peritonsillar abscess in children in the southern district of Israel. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1148–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acharya A., Gurung R., Khanal B., Ghimire A. Bacteriology and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of peritonsillar abscess. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2010;49:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavriel H., Lazarovitch T., Pomortsev A., Eviatar E. Variations in the microbiology of peritonsillar abscess. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:27–31. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0583-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunnergren O., Swanberg J., Molstad S. Incidence, microbiology and clinical history of peritonsillar abscesses. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40:752–755. doi: 10.1080/00365540802040562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jokipii A.M., Jokipii L., Sipila P., Jokinen K. Semiquantitative culture results and pathogenic significance of obligate anaerobes in peritonsillar abscesses. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:957–961. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.5.957-961.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchelmore I.J., Prior A.J., Montgomery P.Q., Tabaqchali S. Microbiological features and pathogenesis of peritonsillar abscesses. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:870–877. doi: 10.1007/BF01691493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuda A., Tanaka H., Kanaya T., Kamata K., Hasegawa M. Peritonsillar abscess: a study of 724 cases in Japan. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002;81:384–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehlers Klug T., Rusan M., Fuursted K., Ovesen T. Fusobacterium necrophorum: most prevalent pathogen in peritonsillar abscess in Denmark. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1467–1472. doi: 10.1086/644616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klug T.E., Henriksen J.J., Fuursted K., Ovesen T. Significant pathogens in peritonsillar abscesses. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:619–627. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Love R.L., Allison R., Chambers S.T. Peritonsillar infection in Christchurch 2006–2008: epidemiology and microbiology. N Z Med J. 2011;124:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sowerby L.J., Hussain Z., Husein M. The epidemiology, antibiotic resistance and post-discharge course of peritonsillar abscesses in London, Ontario. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;42:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1916-0216-42-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klug T.E. Incidence and microbiology of peritonsillar abscess: the influence of season, age, and gender. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1163–1167. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albertz N., Nazar G. Peritonsillar abscess: treatment with immediate tonsillectomy – 10 years of experience. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132:1102–1107. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2012.684399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marom T., Cinamon U., Itskoviz D., Roth Y. Changing trends of peritonsillar abscess. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazur E., Czerwinska E., Korona-Glowniak I., Grochowalska A., Koziol-Montewka M. Epidemiology, clinical history and microbiology of peritonsillar abscess. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:549–554. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2260-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brook I. Aerobic and anaerobic bacteriology of peritonsillar abscess in children. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1981;70:831–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1981.tb06235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jousimies-Somer H., Savolainen S., Makitie A., Ylikoski J. Bacteriologic findings in peritonsillar abscesses in young adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(Suppl. 4):S292–S298. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.supplement_4.s292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brook I. The role of anaerobic bacteria in tonsillitis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parhiscar A., Har-El G. Deep neck abscess: a retrospective review of 210 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:1051–1054. doi: 10.1177/000348940111001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang T.T., Tseng F.Y., Yeh T.H., Hsu C.J., Chen Y.S. Factors affecting the bacteriology of deep neck infection: a retrospective study of 128 patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126:396–401. doi: 10.1080/00016480500395195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rega A.J., Aziz S.R., Ziccardi V.B. Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivities of head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1377–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siu L.K., Yeh K.M., Lin J.C., Fung C.P., Chang F.Y. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:881–887. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J.H., Liu Y.C., Lee S.S., Yen M.Y., Chen Y.S., Wang J.H., et al. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1434–1438. doi: 10.1086/516369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castle S.C. Clinical relevance of age-related immune dysfunction. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:578–585. doi: 10.1086/313947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geerlings S.E., Hoepelman A.I.M. Immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;26:259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang T.T., Liu T.C., Chen P.R., Tseng F.Y., Yeh T.H., Chen Y.S. Deep neck infection: analysis of 185 cases. Head Neck. 2004;26:854–860. doi: 10.1002/hed.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang T.T., Tseng F.Y., Liu T.C., Hsu C.J., Chen Y.S. Deep neck infection in diabetic patients: comparison of clinical picture and outcomes with nondiabetic patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:943–947. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herzon F.S. Harris P. Mosher Award thesis. Peritonsillar abscess: incidence, current management practices, and a proposal for treatment guidelines. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:1–17. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199508002-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Repanos C., Mukherjee P., Alwahab Y. Role of microbiological studies in management of peritonsillar abscess. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:877–879. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108004106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell E.L., Powell J., Samuel J.R., Wilson J.A. A review of the pathogenesis of adult peritonsillar abscess: time for a re-evaluation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1941–1950. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klug T.E., Rusan M., Clemmensen K.K., Fuursted K., Ovesen T. Smoking promotes peritonsillar abscess. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:3163–3167. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ling L.J., Hung S.L., Tseng S.C., Chen Y.T., Chi L.Y., Wu K.M., et al. Association between betel quid chewing, periodontal status and periodontal pathogens. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2001;16:364–369. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2001.160608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lepelletier D., Pinaud V., Le Conte P., Bourigault C., Asseray N., Ballereau F., et al. Peritonsillar abscess (PTA): clinical characteristics, microbiology, drug exposures and outcomes of a large multicenter cohort survey of 412 patients hospitalized in 13 French university hospitals. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:867–873. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2609-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brook I., Frazier E.H., Thompson D.H. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of peritonsillar abscess. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:289–292. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snow D.G., Campbell J.B., Morgan D.W. The microbiology of peritonsillar sepsis. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:553–555. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100116585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muir D.C., Papesch M.E., Allison R.S. Peritonsillar infection in Christchurch 1990–2: microbiology and management. N Z Med J. 1995;108:53–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prior A., Montgomery P., Mitchelmore I., Tabaqchali S. The microbiology and antibiotic treatment of peritonsillar abscesses. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1995;20:219–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1995.tb01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanna B.C., McMullan R., Gallagher G., Hedderwick S. The epidemiology of peritonsillar abscess disease in Northern Ireland. J Infect. 2006;52:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakae F.A., Imamura R., Sennes L.U., Araujo Filho B.C., Tsuji D.H. Microbiology of peritonsillar abscesses. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;72:247–251. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30063-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hidaka H., Kuriyama S., Yano H., Tsuji I., Kobayashi T. Precipitating factors in the pathogenesis of peritonsillar abscess and bacteriological significance of the Streptococcus milleri group. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:527–532. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plum A.W., Mortelliti A.J., Walsh R.E. Microbial flora and antibiotic resistance in peritonsillar abscesses in Upstate New York. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124:875–880. doi: 10.1177/0003489415589364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tachibana T., Orita Y., Takao S., Ogawara Y., Matsuyama Y., Shimizu A., et al. The role of bacteriological studies in the management of peritonsillar abscess. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016;43:648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaikjarv R., Kasenomm P., Jaanimae L., Kivisild A., Roop T., Sepp E., et al. Microbiology of peritonsillar abscess in the South Estonian population. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2016;27:27787. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v27.27787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]