Abstract

The secretion signal of the Caulobacter crescentus S-layer protein (RsaA) was localized to the C-terminal 82 amino acids of the molecule. Protein yield studies showed that 336 or 242 C-terminal residues of RsaA mediated secretion of >50 mg of a cellulase passenger protein per liter to the culture fluids.

The gram-negative bacterium Caulobacter crescentus possesses a paracrystalline protein surface (S) layer covering the outer membrane (24). The S-layer protein (RsaA) is secreted by a dedicated three-component ABC transporter (type I) secretion system (1, 23). Proteins secreted by type I systems typically exhibit two features: (i) an extreme C-terminal secretion signal located within the last 60 amino acids (aa) which is not cleaved as part of the secretion process and (ii) more-N-terminal glycine-rich (“RTX”) motifs, nine-residue sequences which include the consensus sequence GGXGXD. These motifs are responsible for Ca2+ binding and are also thought to be important for proper presentation of the secretion signal to the secretion machinery (3, 10, 18, 19). RsaA possesses six RTX motifs which exactly match the consensus sequence, but the exact location of the secretion signal is unclear (13). It is known that the signal must lie within the 242 C-terminal aa because this portion of RsaA is capable of autonomous secretion (5).

In 1996, no S-layer protein was known to be secreted by a type I secretion system (9). Since that time, the putative S-layer protein of Serratia marcescens (17) and the S-layer proteins of two Campylobacter species (see, e.g., reference 26) have been shown or are suspected to be secreted by type I systems. Problems with defining the C-terminal secretion signals of proteins secreted by type I systems are that these sequences are not cleaved as part of the secretion process and that, as a group, the C termini of such proteins do not display a high degree of primary structural homology (4). Families of type I secreted proteins which exhibit similar C-terminal sequences have been recognized (4), but it is not clear to which current family, if any, the C. crescentus S-layer protein belongs (1, 17, 26).

The experiments reported in this study were undertaken primarily to define the location of the RsaA secretion signal. A secondary goal was of a more applied nature. In a previous report (5), we demonstrated that the last 242 C-terminal aa of RsaA could be used to secrete a 109-aa segment of the infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus surface glycoprotein from C. crescentus. The hybrid protein failed to anchor to the cell surface but formed macroscopic aggregates in the culture fluids which could be recovered in highly purified form by simple coarse filtration of the culture through nylon mesh. This result suggested that the C. crescentus S-layer protein secretion system could be an attractive one for low-cost protein production. For this reason, it was of interest to determine whether other passenger proteins could be secreted when they were linked to the RsaA C terminus and whether smaller portions of the RsaA C terminus could be used to facilitate the secretion and aggregation of these proteins.

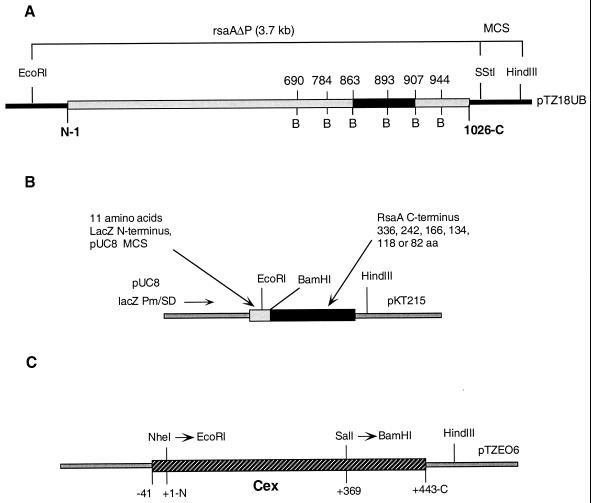

In two earlier reports (5, 6) BamHI linkers were inserted at 24 locations in a version of rsaA lacking its promoter (rsaAΔP). Because of the amino acid composition of RsaA, the G+C content of rsaA, and the restriction enzymes used to create the target sites for linker insertions, 20 of the 24 BamHI sites were ultimately translated as Gly-Ser as a part of full-length RsaA molecules (Fig. 1A). Of interest for this study were the BamHI linker insertions corresponding to the C-terminal aa 690, 785, 908, and 944. In order to better cover the region between aa 785 and 908, BamHI linkers were inserted at positions in rsaAΔP corresponding to aa 863 and 893 using methods similar to those used previously (5, 6). Plasmids bearing DNAs encoding 336, 242, 166, 134, 119, and 82 aa of the RsaA C terminus were constructed by exploiting the newly introduced 5′ BamHI sites in rsaA and the 3′ HindIII site in the plasmid vector pTZ18UB (Table 1; Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Recombinant DNA manipulations. Recombinant DNA manipulations were carried out by standard methods (22) using E. coli DH5α as a host. Growth of bacterial strains, preparation and electroporation of plasmid DNA into E. coli and C. crescentus, and selection of electrotransformants have been previously described (5, 6, 14). (A) rsaAΔP gene showing positions of BamHI linker insertions. The region extending between aa 863 and 907 contains a cluster of RTX sequences. (B) Construction of plasmids bearing genes encoding C-terminal peptides. BamHI-HindIII fragments encoding various portions of the RsaA C terminus were inserted into pUC8. lacZ-directed expression of 3′ rsaA DNA was predicted to yield C-terminal peptides of RsaA carrying an 11-aa N-terminal extension derived from LacZ, the pUC8 multiple cloning site, and BamHI linker DNA. For expression in C. crescentus, each of the six pUC8-based plasmids were ligated to the broad-host-range plasmid pKT215 via their common HindIII sites. (C) Construction of Cex-RsaA hybrid proteins. A DNA fragment encoding the first 368 aa of mature Cex was provided with a 5′ EcoRI site by inserting the NheI/HindIII fragment of pTZEO6 into the XbaI/HindIII sites of pPR510XE; XbaI and NheI possess compatible cohesive termini. A 3′ BamHI site was provided by inserting a BamHI linker from pUC1021 into the unique SalI site of cex. The EcoRI/BamHI fragment was inserted into pUC8-based plasmids carrying DNAs encoding various portions of the RsaA C terminus to create in-frame translational fusions between lacZ, cex, and rsaA sequences. Finally, the pUC8-based plasmids bearing genes encoding the RsaA-Cex hybrid proteins were fused to pKT215 via their common HindIII sites. As a control, the secretion of Cex (369) in the absence of RsaA sequences was investigated. Cex (369) was provided with a translational stop site by inserting the EcoRI/BamHI fragment encoding Cex (369) into pUC8 not carrying any rsaA DNA. Abbreviations: Pm, promoter; SD, Shine-Dalgarno sequence; MCS, multiple cloning site; B, BamHI.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and previously constructed plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| C. crescentus JS4011 | UV-induced mutant of JS4000; this mutant does not synthesize a holdfast organelle | 20 |

| E. coli DH5α | recA endA | Life Technologies, Burlington, Ontario, Canada |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC8 | Cloning and lacZ-based expression vector; Ap | 27 |

| pKT215 | RSF1010-derived cloning vector; Cm Sm | 2 |

| pUC1021 | pUC9 carrying a BamHI linker tagged with a Km gene from Tn903; Ap Km | 7 |

| pPR510XE | Cm version of pUC19 with a modified multiple cloning site; the EcoRI and XbaI sites overlap by 2 nucleotides; Cm | 7 |

| pTZ18U:rsaAΔP(TaqI785BamHI) | rsaAΔP carrying a BamHI linker insertion at a site corresponding to aa 785 of RsaA; Ap | 5 |

| pTZ18U:rsaAΔP(TaqI907BamHI) | rsaAΔP carrying a BamHI linker insertion at a site corresponding to aa 907 of RsaA; Ap | 5 |

| pTZ18U:rsaAΔP(TaqI944BamHI) | rsaAΔP carrying a BamHI linker insertion at a site corresponding to aa 944 of RsaA; Ap | 6 |

| pTZ18U:rsaAΔP(HinP1I690BamHI) | rsaAΔP carrying a BamHI linker insertion at a site corresponding to aa 690 of RsaA; Ap | 6 |

| pTZEO6 | Carries the cex gene of Cellulomonas fimi; the gene has been modified so that it possesses an NheI site at the position corresponding to the N-terminal signal peptidase cleavage site; Ap | 21 |

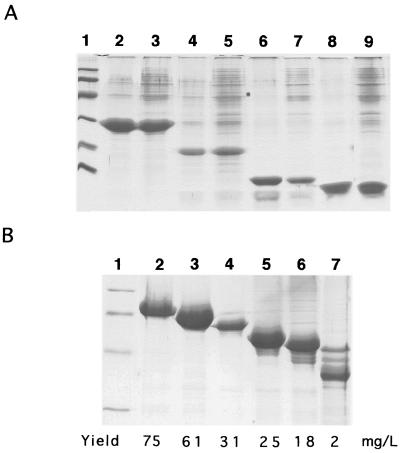

When synthesized by C. crescentus, two of the five C-terminal peptides examined—RsaA242C and RsaA336C—formed macroscopic aggregates in the culture fluids. However, phase-contrast microscopy of cultures synthesizing RsaA166C, RsaA134C, and RsaA119C revealed protein aggregates of a size which could be recovered by coarse filtration of cultures through nylon mesh. Two nylon mesh sizes (350- and 90-μm pore sizes) were used sequentially. Aggregated protein trapped by each mesh was collected, solubilized, and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Figure 2A shows that aggregated protein could be recovered from the culture fluids of cells synthesizing RsaA242C, RsaA166C, RsaA134C, and RsaA119C, indicating that all of these C-terminal peptides of RsaA were capable of autonomous secretion. The autonomous secretion of the 119-aa C-terminal peptide indicated that an RTX motif was not absolutely required for secretion, a conclusion reached for other proteins secreted by type I systems (10, 12, 16, 18).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of aggregated protein recovered from culture fluids by filtration through nylon mesh. (A) C-terminal peptides. C. crescentus was grown in small peptone-yeast extract cultures as previously described (5). Aggregated protein present in the culture fluids of stationary-phase cultures was recovered by gravity filtration through a disk of nylon mesh (2-cm diameter) fitted into a microfiltration apparatus and solubilized in 1 to 4 volumes of 8 M urea–100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) prior to SDS-PAGE (5, 28). Lane 1, molecular mass markers; lanes 2 and 3, RsaA242C; lanes 4 and 5, RsaA166C; lanes 7 and 8, RsaA134C; lanes 8 and 9, RsaA119C. Lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8 contain aggregated protein which collected on mesh with a 350-μm pore size. Lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9 contain aggregated protein which collected on mesh with a 90-μm pore size. Molecular mass markers were of 97.4, 66.2, 42.7, 31.0, 21.5, and 14.4 kDa. (B) Cex-RsaA hybrid proteins. C. crescentus was grown overnight on a rotary shaker in 5 ml of peptone-yeast extract (chloramphenicol, 2 μg/ml) medium. The entire 5-ml culture was then transferred to a 2,800-ml Fernbach flask containing 1,275 ml of M11HIGG medium, a modification of M6Higg medium (25) containing 5 mM imidazolium chloride (1 M stock stock, pH 7.0), 2 mM potassium phosphate (2 M stock stock, pH 6.8), 0.15% glucose, 0.15% l-glutamate (monosodium salt), 1% modified Hunter's mineral base, 0.58 mM CaCl2, and 2 μg of chloramphenicol per ml and grown for a further 72 to 96 h on a model G53 gyratory shaker (New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, N.J.) at approximately 55 rpm. After 72 to 96 h, cultures were sieved through nylon mesh (90-μm diagonal pore size) cut to fit into a 4.5-cm-diameter filtration housing possessing an O-ring seal. The protein aggregates were dislodged from the mesh using a water spray from a wash bottle and washed three times with water by centrifugation (about 1 min, 12,000 × g). A small portion of the protein was solubilized in 1 to 4 volumes of 8 M urea–100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) for SDS-PAGE analysis, and the remainder was lyophilized and weighed. Lane 1, molecular mass markers (see legend to panel A); lane 2, Cex-RsaA336; lane 3, Cex-RsaA242C; lane 4, Cex-RsaA166C; lane 5, Cex-RsaA134C; lane 6, Cex-RsaA119C; lane 7, Cex-RsaA82C. The yield of the Cex passenger portion of the hybrid protein (in milligrams per liter of culture) appears below each lane and was estimated from the numbers of amino acids in the Cex and RsaA portions of the hybrid proteins.

The culture fluids of cells synthesizing RsaA242C, RsaA166C, RsaA134C, and RsaA119C were subjected to ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation (final concentration, 10%, wt/vol) following sequential course filtration through nylon mesh. When the TCA precipitate was examined by SDS-PAGE, all of these proteins were detected, suggesting the presence of a soluble protein fraction or microaggregates which passed through the nylon mesh (data not shown). We also examined the cell pellet resulting from the centrifugation of cells synthesizing RsaA242C (following coarse filtration) by Western analysis using anti-RsaA antibody. An immunoreactive band of the expected molecular mass was detected, indicating likely cosedimentation of bacterium-sized protein aggregates with the cells (data not shown). Clearly, in contrast to what occurs in other systems involving soluble proteins secreted by type I systems, this heterogeneity in the solubility characteristics of the C. crescentus S-layer protein makes an uncomplicated quantification of secretion levels difficult. Estimates from other studies involving soluble proteins teach that secretion levels decline as the size of the C-terminal peptide is reduced (12, 16).

No aggregated material was observed in cultures synthesizing RsaA82C, and none was recovered by coarse filtration. Further, when a sample of cell-free culture fluid was subjected to TCA precipitation, no protein of the predicted molecular mass could be detected by SDS-PAGE.

In another set of experiments, various amounts of the RsaA C terminus (336, 242, 166, 134, 119, and 82 C-terminal aa) were linked to a 369-aa portion of a 443-aa exoglucanase enzyme (Cex) from the gram-positive bacterium Cellulomonas fimi (21). Cex consists of a C-terminal cellulose binding domain and an N-terminal catalytic domain separated by a linker region composed of alternating Pro and Thr residues (15). Normally the enzyme is secreted by a sec-dependent pathway involving cleavage of a 41-aa N-terminal leader peptide (Fig. 1C).

RsaA was linked to Cex (lacking its N-terminal leader peptide) at a site within the cellulose binding domain corresponding to aa 369 of the mature protein (Fig. 1C). Although it was highly unlikely that the 369-aa N-terminal domain of Cex [Cex (369)] was secretion competent in the absence of RsaA information, a control hybrid protein consisting of Cex (369) fused to the LacZα peptide was also constructed and tested.

When expressed in C. crescentus, all cex (369)-rsaA gene fusions yielded aggregated protein which could be recovered from liquid cultures by coarse filtration through nylon mesh. Analysis of this material by SDS-PAGE revealed proteins of a molecular mass expected for the Cex (369)-RsaA hybrid proteins (Fig. 2B), indicating that all of the C-terminal portions of RsaA tested—including the 82 C-terminal aa of the molecule—mediated secretion of Cex into the culture fluids. The amount of aggregated Cex recovered from the medium declined as the number of RsaA C-terminal amino acids included in the Cex-RsaA hybrid proteins was reduced (Fig. 2B). As expected, the control protein lacking RsaA information could not be recovered from the culture fluids by coarse filtration or by TCA precipitation of cell-free culture fluids (data not shown).

Recently, Thompson et al. (26) noted that the 70 C-terminal aa of the Campylobacter fetus S-layer protein and the C. crescentus S-layer protein share a surprising number of conserved residues. Those authors suggested that the secretion of both proteins was likely to depend on a secretion signal lying within 70 aa of the C terminus. The results of our work support this hypothesis.

It is not clear what property of the RsaA C terminus is responsible for the aggregation of the protein. It does not seem to be a Ca2+-dependent phenomenon involving the RTX regions because the 119-aa C-terminal peptide does not possess any of these putative Ca2+ binding motifs, yet it aggregates in the culture fluids. At the moment, we assume that this characteristic is a residual consequence of the fact that RsaA is a structure-forming, self-assembling protein, and self-aggregation is therefore not unexpected. Although the presence or absence of the RTX sequences is unlikely to be responsible for the aggregation of hybrid proteins, these sequences are likely to affect the kinetics and efficiency of the secretion process (11). It has also been shown that the importance of including RTX motifs in a hybrid protein varies with the particular passenger protein (10, 18, 19).

The results of this work are important from the standpoint of using the C. crescentus S-layer protein secretion system for the production of heterologous proteins. The 336 and 242 C-terminal aa of RsaA mediated high-level secretion (>50 mg/liter) of Cex, a polypeptide we consider to be of typical size (Fig. 2B). We also have preliminary evidence that the catalytic domain of Cex in the aggregated hybrid proteins is active, with a specific activity of at least 2% of reported values for native Cex. We are currently working to increase the specific activities of these particulate RsaA-Cex hybrid proteins.

The secretion levels reported here are higher than that reported for any other characterized type I system. This is probably because the S-layer protein accounts for 10 to 12% of total cell protein; thus, the RsaA secretion machinery must handle large amounts of its substrate protein. Yields of aggregated protein similar to those observed for Cex have also been obtained for a 250-aa portion of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase (PhoA), portions (100 to 200 aa) of the envelope and capsid proteins from the salmonid viruses infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus and infectious pancreatic necrosis virus, and 100 aa of a silk protein from the spider Araneus diadematus (J. F. Nomellini and J. Smit, unpublished results). Whether the yields observed for these proteins can be extended to other passenger proteins awaits further experiments and the use of the system by us and others.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ian Bosdet for assistance throughout the course of this study.

This work was supported by an operating grant to J.S. from the Canadian Natural Science and Engineering Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Awram P, Smit J. The Caulobacter crescentus paracrystalline S-layer protein is secreted by an ABC transporter (type I) secretion apparatus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3062–3069. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3062-3069.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagdasarian M, Lurz R, Ruckert B, Franklin F C H, Bagdasarian M M, Timmis K N. Specific-purpose cloning vectors. II. Broad-host-range, high copy number RSF1010-derived vectors, and a host-vector system for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene. 1981;16:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann U, Wu S, Flaherty M, McKay D B. Three dimensional structure of the alkaline protease of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a two domain protein with a calcium-binding parallel beta roll motif. EMBO J. 1993;12:3357–3364. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binet R, Letoffe S, Ghigo J-M, Delepelaire P, Wandersman C. Protein secretion by gram-negative bacterial ABC exporters—a review. Gene. 1997;192:7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00829-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingle W H, Nomellini J F, Smit J. Linker mutagenesis of the Caulobacter crescentus S-layer protein: toward a definition of an N-terminal anchoring region and a C-terminal secretion signal and the potential for heterologous protein secretion. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:601–611. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.601-611.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bingle W H, Nomellini J F, Smit J. Cell-surface display of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain K pilin peptide within the paracrystalline S-layer of Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:277–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5711932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bingle W H, Smit J. A method of tagging specific-purpose linkers with an antibiotic resistance gene for linker mutagenesis using a selectable marker. BioTechniques. 1991;10:150–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bingle W H, Smit J. High-level expression vectors for Caulobacter crescentus incorporating the transcription/translation initiation regions of the paracrystalline surface-layer protein gene. Plasmid. 1990;24:143–149. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(90)90016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boot H J, Pouwels P H. Expression, secretion and antigenic variation of bacterial S-layer proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1117–1123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.711442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duong F, Lazdunski A, Murgier M. Protein secretion by heterologous bacterial ABC-transporters: the C-terminus secretion signal of the secreted protein confers high recognition specificity. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:459–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Femlee T, Welch R A. Alterations of amino acid repeats in the Escherichia coli hemolysin affect cytolytic activity and secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5269–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghigo J-M, Wandersman C. A carboxy-terminal four amino acid-motif is required for secretion of the metalloprotease PrtG through the Erwinia chrysanthemi protease secretion pathway. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8979–8985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilchrist A, Fisher J, Smit J. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the gene encoding the Caulobacter crescentus paracrystalline surface layer protein. Can J Microbiol. 1992;38:193–202. doi: 10.1139/m92-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilchrist A, Smit J. Transformation of freshwater and marine caulobacters by electroporation. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:921–925. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.921-925.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilkes N R, Henrissat B, Kilburn D G, Miller R C, Jr, Warren R A J. Domains in microbial β-1,4-glycanases: sequence conservation, function, and enzyme families. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:303–315. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.2.303-315.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarchau T, Chakrobarty T, Garcia F, Goebel W. Selection for transport competence of C-terminal polypeptides derived from Escherichia coli hemolysin: the shortest peptide capable of autonomous HylB/HylD-dependent secretion comprises the C-terminal 62 amino acids of HylA. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00279750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawai E, Akatsuka H, Idei A, Shibatani T, Omori K. Serratia marcescens S-layer protein is secreted extracellularly via an ATP-binding cassette exporter, the Lip system. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:941–952. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenny B, Haigh R, Holland I B. Analysis of the haemolysin transport process through the secretion from Escherichia coli of PCM, CAT or β-galactosidase fused to the Hly C-terminal signal domain. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2557–2568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Letoffe S, Wandersman C. Secretion of CyaA-PrtB and HylA-PrtB fusion proteins in Escherichia coli: involvement of the glycine-rich repeat domain of Erwinia chrysanthemi protease B. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4920–4927. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.4920-4927.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong C, Wong M L Y, Smit J. Attachment of the adhesive holdfast organelle to the cellular stalk of Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1448–1456. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1448-1456.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ong E, Gilkes N R, Miller R C, Jr, Warren R A J, Kilburn D G. The cellulose-binding domain of an exoglucanase from Cellulomonas fimi: production in Escherichia coli and characterization of the polypeptide. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1993;42:401–409. doi: 10.1002/bit.260420402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smit J, Agabian N. Cloning of the major protein of the Caulobacter crescentus periodic surface layer: detection and characterization of the cloned peptide by protein expression assays. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:1137–1145. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.1137-1145.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smit J, Engelhardt H, Volker S, Smith S H, Baumeister W. The S-layer of Caulobacter crescentus: three-dimensional image reconstruction and structure analysis by electron microscopy. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6527–6538. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6527-6538.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smit J, Hermodson M, Agabian N. Caulobacter crescentus pilin: purification, chemical characterization and amino-terminal amino acid sequence of a structural protein regulated during development. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:3092–3097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson S A, Shedd O M, Ray K C, Beins M H, Jorgensen J P, Blaser M J. Campylobacter fetus surface layer proteins are transported by a type I secretion system. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6450–6458. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6450-6458.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker S G, Smith S H, Smit J. Isolation and comparison of the paracrystalline surface layer proteins of freshwater caulobacters. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1783–1792. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.1783-1792.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]