Abstract

Objective: To explore the prevalence of periodontal disease in middle-aged and elderly patients and analyze its influencing factors. Methods: A total of 521 patients admitted to the Department of Stomatology of Fuyang District Chinese Medicine Hospital of Hangzhou from January 2019 to January 2022 were retrospectively collected as study subjects, including 176 patients aged 35-44 years old, 175 patients aged 45-64 years old, and 170 patients aged 65-74 years old. Community Periodontal Index (CPI) probe was used to detect gingival bleeding, periodontal pockets and attachment loss, and the prevalence of periodontal disease and its influencing factors were analyzed. Results: In the age group of 35-44, gingival bleeding was detected in 165 (93.75%) cases and dental calculus was detected in 176 (100.00%) cases; in the age group of 45-64, gingival bleeding was detected in 163 (93.14%) cases and dental calculus was detected in 161 (92.00%) cases; in the age group of 65-74, gingival bleeding was detected in 150 (88.24%) cases and dental calculus was detected in 162 (95.29%) cases. There were statistically significant differences in the detection rates of shallow periodontal pockets, deep periodontal pockets, and loss of periodontal attachment among the three groups (P<0.05). There wasalso asignificant difference in the detection rate of periodontitis among the three groups (P<0.05). Univariate analysis showed that gender, age, place of residence, smoking, alcohol consumption, brushing frequency, and dental cleaning in the past year were all associated with the occurrence of periodontitis (P<0.05). Logistic multi-factor regression analysis showed that age was a risk factor for the development of periodontitis in middle-aged and elderly patients (P<0.05). Conclusion: The prevalence of periodontal disease in middle-aged and elderly individuals is high, with a high prevalence of gingival bleeding and shallow periodontal pockets. Age is an influencing factor on the incidence of periodontitis in middle-aged and elderly individuals.

Keywords: Middle-aged and elderly patients, periodontal disease, influencing factors, periodontitis

Introduction

Oral health has been proposed as one of the hallmarks of modern human civilization [1], and reflects the health and well-being of a person throughout life [2]. At present, studies have clearly found that oral diseases are closely related to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, kidney diseases and other systemic diseases [3,4]. However, oral health of middle-aged and elderly population in China is still not optimal, and three national epidemiological surveys conducted in 1983, 1995 and 2005 showed that the incidence of dental caries and dental fluorosis is relatively high in the middle-aged and elderly population in China [5,6].

With the rapid socioeconomic development in China, great changes have taken place in the lifestyle and dietary habits of the residents. On the one hand, the trend of aging has significantly increased the proportion of middle-aged and elderly population, and on the other hand, the above changes have also affected the dental health of the residents. Data show that the current prevalence of periodontal disease in the elderly is as high as 55.7%, and the percentage of completely edentulous elderly reaches 6.9%, and the research has pointed out that periodontal disease not only brings greater economic burden to the patients themselves, but also becomes a risk factor for a variety of cardiovascular diseases [7]. Currently, periodontal diseases are treated in a variety of ways, including conservative treatment, and surgical intervention. Timely and effective treatment has positive significance in improving the periodontal health of patients [8]. Compared to young individuals, middle-aged and elderly individuals are more likely to develop periodontal disease due to multiple factors such as education level, living environment, and economic conditions, and that middle-aged and elder groups generally pay less attention to periodontal health. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the periodontal disease in middle-aged and elderly population, so as to clarify the prevalence of periodontal disease in this population, formulate targeted intervention measures, and lay a good foundation for improving the dental health of the residents.

Materials and methods

Target population

Five hundred and twenty-one patients who attended the Department of Stomatology of Fuyang District Chinese Medicine Hospital of Hangzhou from January 2019 to January 2022 were retrospectively collected as study subjects, including 176 patients in the age group of 35-44, 175 patients in the age group of 45-64, and 170 patients in the age group of 65-74. The study was approved by the ethics committees of Fuyang District Chinese Medicine Hospital of Hangzhou (No. NCT01258634), and the study data were also used with informed consent of the patients.

Inclusion criteria

(1) those who admitted to Fuyang District Chinese Medicine Hospital of Hangzhou and received periodontal treatments for gingivitis, periodontitis, periodontal atrophy and other periodontal diseases; (2) those with complete medical records.

Exclusion criteria

(1) those with concurrent mental or neurological disorders resulting in unconsciousness; (2) those with concurrent hearing, visual, and speech system dysfunction; (3) those with concurrent serious medical diseases; (4) those with severe periodontal defects due to trauma or other causes; or (5) those with other oral diseases that affected the results of the study.

Investigation method

Sample size calculation (Formula)

|

α=0.05, two-sided test, U0.05=1.96; the positive rate was predicted by reviewing the literature (p=15%, q=1-p, error δ=2.5%). Through calculation, a sample size of about 384 was obtained. Considering the incomplete data, the sample size was increased by 20%, and finally the total number of subjects should not be less than 461.

Data collection

(1) General clinical data, including gender, age, place of residence (in the past year), smoking, alcohol consumption, frequency of tooth brushing, number of dental cleaning in the past year were collected. (2) Oral health examination. According to the examination standards of the Fourth National Oral Health Epidemiological Survey [9], the prevalence of calculus, shallow periodontal pockets, deep periodontal pockets, attachment loss, and periodontitis were examined. The periodontal health rate and incidence of periodontitis were calculated.

Quality control

The collected data were input into an Excel sheet by two researchers, who were specially trained in advance to master the requirements of data collection and entry process, to ensure that the data were error-free.

Statistical methods

The collected data were processed using SPSS 26.0 statistical software. The measurement data were analyzed using t-test and expressed as (x̅ ± s). The count data were expressed as [n (%)], and the difference between the two groups and multiple groups were compared using χ2 test. Logistic regression model was used to analyze the factors influencing periodontitis. P<0.05 indicated a significant difference [10].

Results

Baseline data

A total of 521 patients were investigated, including 176 (33.78%) patients in the age group of 35-44, 175 (33.59%) patients in the age group of 45-64, and 170 (32.63%) patients in the age group of 65-74. The average age of the examined population was (55.98±4.30) years old, and 263 (50.48%) patients were males and 258 (49.52%) were females (Table 1).

Table 1.

The detection rate of gingival bleeding and tartar [n (%)]

| Age group | Subgroup | Number of subjects | Gingival bleeding | Dental calculus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35-44 | Urban | 89 | 85 (95.51) | 89 (100.00) |

| Rural | 87 | 80 (91.95) | 87 (100.00) | |

| Male | 90 | 86 (95.56) | 90 (100.00) | |

| Female | 86 | 79 (91.86) | 86 (100.00) | |

| Total | 176 | 165 (93.75) | 176 (100.00) | |

| 45-64 | Urban | 90 | 82 (91.11) | 82 (91.11) |

| Rural | 85 | 81 (95.29) | 79 (92.94) | |

| Male | 87 | 80 (91.95) | 78 (89.66) | |

| Female | 88 | 83 (94.32) | 83 (94.32) | |

| Total | 175 | 163 (93.14) | 161 (92.00) | |

| 65-74 | Urban | 89 | 78 (87.64) | 86 (96.63) |

| Rural | 81 | 72 (88.89) | 76 (93.83) | |

| Male | 86 | 77 (89.53) | 84 (97.67) | |

| Female | 84 | 73 (86.90) | 78 (92.86) | |

| Total | 170 | 150 (88.24) | 162 (95.29) | |

| Total | 521 | 478 (91.75) | 499 (95.78) | |

Periodontal disease statistics

The detection rate of gingival bleeding and dental calculus

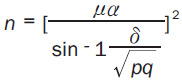

Among the middle-aged and elderly patients, there were 165 (93.75%) cases of gingival bleeding and 176 (100.00%) cases of dental calculus in the age group of 35-44; there were 163 (93.14%) cases of gingival bleeding and 161 (92.00%) cases of dental calculus in the age group of 45-64; and there were 150 (88.24%) cases of gingival bleeding and 162 (95.29%) cases of dental calculus in the age group of 65-74. The detection rate of gingival bleeding and dental calculus among the three groups showed no significant differences (all P>0.05) (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Detection rate of gingival bleeding and tartar. A. Age group of 35-44, B. Age group of 45-64, C. Age group of 65-74.

Detection rate of periodontal pockets and periodontal attachment loss

In the 35-44 age group , there were 67 (38.07%) cases of shallow periodontal pockets, 4 (5.97%) cases of deep periodontal pockets, and 56 (31.82%) cases of periodontal attachment loss; in the 45-64 age group, there were 108 (61.71%) cases of shallow periodontal pockets, 20 (11.43%) cases of deep periodontal pockets, and 132 (75.43%) cases of periodontal attachment loss; in the 65-74 age group, there were 89 (52.35%) cases of shallow periodontal pockets, 15 (8.82%) cases of deep periodontal pockets, and 149 (87.65%) cases of periodontal attachment loss. There were significant differences among the three groups in the detection rate of shallow and deep periodontal pockets as well as periodontal attachment loss. (χ2 =19.914, P<0.001; χ2 =11.274, P=0.004; χ2 =131.305, P<0.001). A pairwise comparison showed that the detection rate of deep periodontal pockets was higher in urban than in rural areas in the 35-44 age group, and the detection rate of shallow periodontal pockets were higher in men than in women in the 55-64 age group (all P<0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The detection rate of periodontal pockets and periodontal attachment loss [n (%)]

| Age group | Subgroup | Number of subjects | Shallow periodontal pockets | Deep periodontal pockets | Loss of periodontal attachment | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35-44 | Urban | 89 | 32 (35.96) | 4 (4.49)* | 29 (32.58) | 2.659 | 0.004 |

| Rural | 87 | 35 (40.23) | 0 (0.00) | 27 (31.03) | |||

| Male | 90 | 36 (40.00) | 1 (1.11) | 30 (33.33) | 0.698 | 0.215 | |

| Female | 86 | 31 (36.05) | 3 (3.49) | 26 (30.23) | |||

| Total | 176 | 67 (38.07) | 4 (5.97) | 56 (31.82) | - | - | |

| 45-64 | Urban | 90 | 54 (60.00) | 9 (10.00) | 70 (77.78) | 0.894 | 0.265 |

| Rural | 85 | 54 (63.53) | 11 (12.94) | 62 (72.94) | |||

| Male | 87 | 68 (78.16)# | 14 (16.09) | 78 (89.66)# | 3.264 | <0.001 | |

| Female | 88 | 40 (45.45) | 6 (6.82) | 54 (61.36) | |||

| Total | 175 | 108 (61.71) | 20 (11.43) | 132 (75.43) | - | - | |

| 65-74 | Urban | 89 | 46 (51.69) | 10 (11.24) | 81 (91.01) | 0.115 | 0.685 |

| Rural | 81 | 43 (53.09) | 5 (6.17) | 68 (83.95) | |||

| Male | 86 | 48 (55.81) | 8 (9.30) | 76 (88.37) | 0.698 | 0.451 | |

| Female | 84 | 41 (48.81) | 7 (8.33) | 73 (86.90) | |||

| Total | 170 | 89 (52.35) | 15 (8.82) | 149 (87.65) | - | - | |

| Total | 521 | 264 (50.67) | 39 (7.49) | 337 (64.68) | - | - | |

Note: Compared to the same age group of females;

P<0.05.

Compared to the same age group of rural residents;

P<0.05.

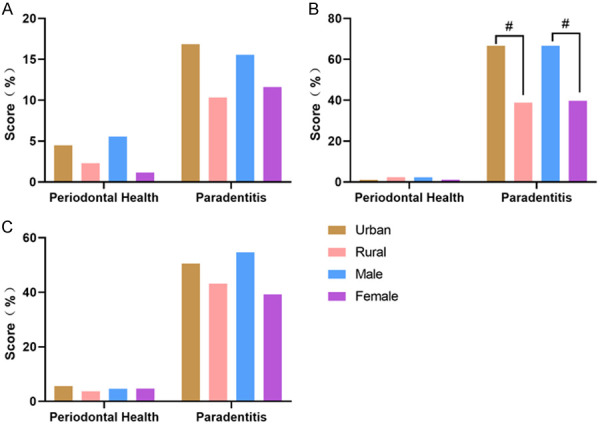

Periodontal health and periodontitis detection rates

The detection rate of periodontitis and periodontal health rate was 3.41% and 13.64% in the 35-44 age group, 1.71% and 53.14% in the 45-64 age group, and 4.71% and 47.06% in the 55-64 age group, exhibiting significant differences among the three groups (χ2 =54.756, P<0.001). A pairwise comparison showed that the detection rate of periodontitis was higher in urban than in rural areas in the 55-64 age group, and was higher in men than in women in the 65-74 age group (P<0.05) (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Table 3.

The periodontal health and periodontitis detection rate in middle-aged and elderly population

| Age group | Subgroup | Number of subjects | Periodontal health | Periodontitis | χ2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Number of cases | Detection rate (%) | Number of cases | Detection rate (%) | |||||

| 35-44 | Urban | 89 | 4 | 4.49 | 15 | 16.85 | 1.583 | 0.208 |

| Rural | 87 | 2 | 2.30 | 9 | 10.34 | |||

| Male | 90 | 5 | 5.56 | 14 | 15.56 | 0.576 | 0.448 | |

| Female | 86 | 1 | 1.16 | 10 | 11.63 | |||

| Total | 176 | 6 | 3.41 | 24 | 13.64 | - | - | |

| 45-64 | Urban | 90 | 1 | 1.11 | 60* | 66.67 | 13.609 | <0.001 |

| Rural | 85 | 2 | 2.35 | 33 | 38.82 | |||

| Male | 87 | 2 | 2.30 | 58# | 66.67 | 12.707 | <0.001 | |

| Female | 88 | 1 | 1.14 | 35 | 39.77 | |||

| Total | 175 | 3 | 1.71 | 93 | 53.14 | - | - | |

| 65-74 | Urban | 89 | 5 | 5.62 | 45 | 50.56 | 0.920 | 0.337 |

| Rural | 81 | 3 | 3.70 | 35 | 43.21 | |||

| Male | 86 | 4 | 4.65 | 47* | 54.65 | 4.027 | 0.045 | |

| Female | 84 | 4 | 4.76 | 33 | 39.29 | |||

| Total | 170 | 8 | 4.71 | 80 | 47.06 | - | - | |

| Total | 521 | 17 | 3.26 | 197 | 37.81 | - | - | |

Note: Compared to the same age group of females;

P<0.05.

Compared to the same age group of rural residents;

P<0.05.

Figure 2.

Analysis of periodontal health and periodontitis detection rate. A. Age group of 35-44, B. Age group of 45-64, C. Age group of 65-74. #P<0.05.

Analysis of factors influencing periodontitis

Univariate analysis showed that gender, age, place of residence, smoking, alcohol consumption, frequency of brushing, and dental cleaning in the past year were all associated with the occurrence of periodontitis (P<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of univariate analysis of periodontitis

| Health status | Number of people (n=521) | Periodontitis (n=197) | χ2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Number of cases | Detection rate (%) | |||||

| Gender | Male | 263 | 119 | 45.25 | 12.486 | <0.001 |

| Female | 258 | 78 | 30.23 | |||

| Age | 35-44 | 176 | 24 | 13.64 | 67.419 | <0.001 |

| 45-64 | 175 | 93 | 53.14 | |||

| 65-74 | 170 | 80 | 47.06 | |||

| Place of residence | Urban | 268 | 120 | 44.78 | 11.383 | 0.001 |

| Rural | 253 | 77 | 30.43 | |||

| Smoking | Yes | 356 | 154 | 43.26 | 14.181 | <0.001 |

| No | 165 | 43 | 26.06 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | Yes | 213 | 123 | 57.75 | 60.89 | <0.001 |

| No | 308 | 74 | 24.03 | |||

| Frequency of brushing | <1 time per day | 332 | 164 | 49.40 | 52.242 | <0.001 |

| ≥1 time per day | 189 | 33 | 17.46 | |||

| Dental cleaning in the past year | Yes | 120 | 67 | 55.83 | 21.534 | <0.001 |

| No | 401 | 130 | 32.42 | |||

Logistic regression analysis of influencing factors related to periodontitis

Based on the sample size of 521 patients in this study, presence of periodontitis was used as a dependent variable (0= no periodontitis, 1= periodontitis), and factors with P<0.1 in the univariate analysis were used as independent variables (including gender, age, place of residence, smoking, alcohol consumption, frequency of brushing, and dental cleaning in the past year) (Table 5). Logistic regression analysis models were developed. The analysis showed that age was an independent risk factor influencing the development of periodontitis in the middle-aged and elderly population (P<0.05) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Assignment of independent variables

| Independent variable | Assignment 0 | Assignment 1 | Assignment 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Female | |

| Age | 35-44 | 45-64 | 65-74 |

| Place of residence | Urban | Rural | |

| Smoking | No | Yes | |

| Alcohol consumption | No | Yes | |

| Brushing frequency | <1 time per day | ≥1 time per day | |

| Tooth cleaning in the past year | No | Yes |

Table 6.

Logistic regression analysis of influencing factors related to periodontitis

| Variable | β | SE | Wald | 95% CI | Exp (B) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 2.156 | 0.452 | 22.705 | 3.558-20.964 | 3.558 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 1.025 | 0.698 | 5.124 | 0.954-1.125 | 2.112 | 0.064 |

| Place of residence | 1.098 | 0.445 | 4.125 | 0.698-1.041 | 1.658 | 0.451 |

| Smoking | 1.521 | 0.625 | 3.012 | 0.598-0.654 | 0.685 | 0.065 |

| Alcohol consumption | 1.001 | 0.987 | 1.569 | 0.695-0.874 | 0.559 | 0.078 |

| Brushing frequency | 1.265 | 0.8859 | 1.663 | 0.623-0.984 | 0.625 | 0.061 |

| Tooth cleaning in the past year | 1.712 | 0.698 | 1.332 | 1.012-1.652 | 0.698 | 0.071 |

Discussion

Oral diseases are common diseases affecting human health [11], and survey data show that the prevalence of dental caries is as high as 67.0% in children, the prevalence of permanent pressure caries reaches 59.9% in the middle-aged group, and about 7% of adults over 65 years old are edentulous. The detection rate of gingival teeth and dental calculus is also high in various age groups, suggesting that overall oral health is generally poor [12,13]. Influenced by traditional concepts, Chinese people pay less attention to oral health, but in recent years, with the improvement of the overall quality of life and living standards, the demand for oral health has been increasing, and oral health has become a more prominent health issue of public concern at this stage [14,15].

In this study, the prevalence of periodontal diseases was analyzed by including 521 middle-aged and elderly individuals, and the results found that the total prevalence of gingival bleeding among the 521 middle-aged and elderly individuals was 91.75%, the total prevalence of calculus was 95.78%, and the total prevalence of shallow periodontal pockets was 50.67%; the total prevalence of deep periodontal pockets was 7.49%, and the total prevalence of periodontal attachment loss was 64.68%; the total prevalence of periodontitis was 37.81%, and the periodontal health rate was only 3.26%. A survey on the periodontal health status of 328 middle-aged and elderly patients from January 2017 to July 2017 showed that 71.04% of 328 patients were periodontal unhealthy individuals, and the main indicators of periodontal unhealthiness included gingival bleeding, periodontal pockets, attachment loss, and tooth loss [16]. A stratified, multistage, equal-volume random sample of 447 residents found that the prevalence of gingival bleeding and dental calculus as well as the proportion of periodontal attachment loss were 98.7%, 98.0%, and 76.5%, respectively [17]. The results of the present study were partially similar to those of the above two studies. For example, the main types of periodontal diseases in the investigated population were gingival bleeding, periodontal pockets, and attachment loss, and some of the differences may be related to differences in the geographical environment and dietary habits of the investigated population.

In addition, by grouping the investigated population according to age, place of residence and gender, some indicators had significant differences, such as the prevalence of shallow periodontal pockets, periodontal attachment loss and periodontitis was significantly higher in men than in women in the age group of 55-64, the prevalence of periodontitis was significantly higher in urban than in rural areas, and the prevalence of deep periodontal pockets was significantly higher in urban than in rural areas in the age group of 35-44, which were similar to the findings of other study [18]. A survey on the periodontal health status of middle-aged and elderly population in a central urban area pointed out that there were significant differences in periodontal health rates among the individuals of different ages, and it showed that with an increase of age, individuals pay less attention to oral health, which may be one of the reasons for the high prevalence of periodontal diseases in the elderly population [19]. Another study has shown that individuals with higher education and cleaner living environment pay more attention to oral health, suggesting that living environment may affect individuals’ concern for oral health [20].

The study conducted univariate and multifactorial logistic regression analyses regarding the risk factors affecting the development of periodontitis in middle-aged and elderly population, and the results showed that gender, age, place of residence, smoking, alcohol consumption, frequency of brushing, and dental cleaning in the past year were all associated with the development of periodontitis, and age was an independent risk factor affecting the development of periodontitis in middle-aged and elderly population. Abou El Fadl et al. [21] conducted a health survey on 5954 adults age over 20 years old, and found that the prevalence of periodontitis were significantly higher among the elderly, illiterate, smokers and rural residents, and further analysis conducted by the researcher revealed that advanced age and history of diabetes were the main factors leading to tooth loss. Humagain and Adhikari [22] conducted an assessment of periodontal status among people in the Chepang Hill district of Nepal, and noted a significant increase in loss of attachment and Community Periodontal Index (CPI) with the increase of age, suggesting that interventions should be intensified for the elderly population. We believed that gender, place of residence, smoking, alcohol consumption, frequency of brushing, and dental cleaning habits in the past year would have an impact on the oral health condition, with smoking and alcohol consumption, for example, disrupting the oral microbial balance of patients, leading to the suppression of probiotic bacteria and increasing the chance of periodontal inflammation [22,23]. We found that age was an independent risk factor for the development of periodontitis, and the reasons might be: (1) age increases the incidence of local plaque, calculus, and food impaction in the oral cavity, along with decreased metabolic capacity and immune capacity, thus increasing the incidence of periodontal inflammation [24]; (2) age can affect habits that are beneficial to oral health, such as forgetting to brush teeth and rinse mouth after meals; and (3) the elderly have low acceptance of oral health knowledge and poor compliance with treatment.

In conclusion, the condition of periodontal disease in middle-aged and elderly population is not good, and the prevalence of gingival bleeding and shallow periodontal pockets is high. Age has a significant impact on the incidence of periodontitis in middle-aged and elderly population, and oral prevention and health care should be strengthened for them. The innovation of this study lies in the analysis of the current prevalence of periodontal disease and its influencing factors in middle-aged and elderly population by including middle-aged and elderly groups, which provides detailed data support for the improvement of periodontal health in middle-aged and elderly population. The limitation of this study is that the patients included were from a single center, Fuyang District Chinese Medicine Hospital of Hangzhou, which may cause bias. It is proposed to conduct a multicenter study at a later stage to improve the accuracy of the data.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, Listl S, Celeste RK, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Kearns C, Benzian H, Allison P, Watt RG. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394:249–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsuchida S, Nakayama T. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination in oral disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5488. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solbiati J, Frias-Lopez J. Metatranscriptome of the oral microbiome in health and disease. J Dent Res. 2018;97:492–500. doi: 10.1177/0022034518761644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiorillo L. Oral health: the first step to well-being. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55:676. doi: 10.3390/medicina55100676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casamassimo PS, Flaitz CM, Hammersmith K, Sangvai S, Kumar A. Recognizing the relationship between disorders in the oral cavity and systemic disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018;65:1007–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isola G. The impact of diet, nutrition and nutraceuticals on oral and periodontal health. Nutrients. 2020;12:2724. doi: 10.3390/nu12092724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer RG, Lira Junior R, Retamal-Valdes B, Figueiredo LC, Malheiros Z, Stewart B, Feres M. Periodontal disease and its impact on general health in Latin America. Section V: treatment of periodontitis. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34(supp1 1):e026. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janakiram C, Dye BA. A public health approach for prevention of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2020;84:202–214. doi: 10.1111/prd.12337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genco RJ, Sanz M. Clinical and public health implications of periodontal and systemic diseases: an overview. Periodontol 2000. 2020;83:7–13. doi: 10.1111/prd.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nwizu N, Wactawski-Wende J, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and cancer: epidemiologic studies and possible mechanisms. Periodontol 2000. 2020;83:213–233. doi: 10.1111/prd.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenartova M, Tesinska B, Janatova T, Hrebicek O, Mysak J, Janata J, Najmanova L. The oral microbiome in periodontal health. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:629723. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.629723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nazir M, Al-Ansari A, Al-Khalifa K, Alhareky M, Gaffar B, Almas K. Global prevalence of periodontal disease and lack of its surveillance. ScientificWorldJournal. 2020;2020:2146160. doi: 10.1155/2020/2146160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siebert T, Malachovsky I, Statelova D, Stenchlakova B. Motivational interviewing for improving periodontal health. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2020;121:670–674. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2020_110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scannapieco FA, Gershovich E. The prevention of periodontal disease-an overview. Periodontol 2000. 2020;84:9–13. doi: 10.1111/prd.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietrich T, Ower P, Tank M, West NX, Walter C, Needleman I, Hughes FJ, Wadia R, Milward MR, Hodge PJ, Chapple ILC. Periodontal diagnosis in the context of the 2017 classification system of periodontal diseases and conditions - implementation in clinical practice. Br Dent J. 2019;226:16–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2019.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer RG, Gomes Filho IS, Cruz SSD, Oliveira VB, Lira-Junior R, Scannapieco FA, Rego RO. What is the future of periodontal medicine? Braz Oral Res. 2021;35(Supp 2):e102. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2021.vol35.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S. Evidence-based update on diagnosis and management of gingivitis and periodontitis. Dent Clin North Am. 2019;63:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu W, Cao Y, Dong L, Zhu Y, Wu Y, Lv Z, Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Li C. Periodontal therapy for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in people with periodontitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12:CD009197. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009197.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight ET, Murray Thomson W. A public health perspective on personalized periodontics. Periodontol 2000. 2018;78:195–200. doi: 10.1111/prd.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamanti I, Berdouses ED, Kavvadia K, Arapostathis KN, Polychronopoulou A, Oulis CJ. Oral hygiene and periodontal condition of 12- and 15-year-old Greek adolescents. Socio-behavioural risk indicators, self-rated oral health and changes in 10 years. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2021;22:98–106. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2021.22.02.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abou El Fadl RK, Abdel Fattah MA, Helmi MA, Wassel MO, Badran AS, Elgendi HAA, Allam MEE, Mokhtar AG, Saad Eldin M, Ibrahim EAY, Elgarba BM, Mehlis M. Periodontal diseases and potential risk factors in Egyptian adult population-results from a national cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0258958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humagain M, Adhikari S. Assessment of periodontal status of the people in chepang hill tract of nepal: a cross sectional study. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2018;16:206–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shariff JA, Burkett S, Watson CW, Cheng B, Noble JM, Papapanou PN. Periodontal status among elderly inhabitants of northern Manhattan: the WHICAP ancillary study of oral health. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:909–919. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maia CVR, Mendes FM, Normando D. The impact of oral health on quality of life of urban and riverine populations of the Amazon: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0208096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]