Abstract

Lineage-based species definitions applying coalescent approaches to species delimitation have become increasingly popular. Yet, the application of these methods and the recognition of lineage-only definitions have recently been questioned. Species delimitation criteria that explicitly consider both lineages and evidence for ecological role shifts provide an opportunity to incorporate ecologically meaningful data from multiple sources in studies of species boundaries. Here, such criteria were applied to a problematic group of mycoheterotrophic orchids, the Corallorhiza striata complex, analyzing genomic, morphological, phenological, reproductive-mode, niche, and fungal host data. A recently developed method for generating genomic polymorphism data–ISSRseq–demonstrates evidence for four distinct lineages, including a previously unidentified lineage in the Coast Ranges and Cascades of California and Oregon, USA. There is divergence in morphology, phenology, reproductive mode, and fungal associates among the four lineages. Integrative analyses, conducted in population assignment and redundancy analysis frameworks, provide evidence of distinct genomic lineages and a similar pattern of divergence in the ‘extended’ data, albeit with weaker signal. However, none of the extended datasets fully satisfy the condition of a significant role shift, which requires evidence of fixed differences. The four lineages identified in the current study are recognized at the level of variety, short of comprising different species. This study represents the most comprehensive application of ‘lineage + role’ to date and illustrates the advantages of such an approach.

Keywords: Integrative species delimitation, ISSRseq, SNP data, species concept, species boundaries, Orchidaceae

1. Introduction

Species are a (or perhaps the) fundamental unit of biodiversity, conservation, evolution, and ecology; our understanding of biodiversity, and the scientific studies that deal with it, depend on what we empirically designate as species (e.g. Wright and Huxley, 1940; Mayr, 1942; Dobzhansky, 1950; Hennig, 1966; Sneath and Sokal, 1973; Wiley, 1978; Donoghue, 1985; Sterelny, 1999; Wilson, 1999; Sites and Marshall, 2004; Wiens, 2007; Camargo and Sites, 2013; Wilson, 2017; Pedraza-Marrón et al., 2019; Hillis et al., 2021). Focusing on the species concept (what species are; Mayden, 1997) most often points to the idea of an evolutionary lineage (metapopulation through time) as key, as described by Simpson (1951) in his Evolutionary Species Concept (ESC). Correspondingly, focusing on identifying such lineages has become a key aspect of species delimitation (de Queiroz, 1998; 2005; 2007; Reeves and Richards, 2011) in part because genomic data make reconstructing them increasingly tractable, even under a variety of confounding processes [incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), gene flow, gene transfer (Carstens and Knowles, 2007; Leaché and Fujita, 2010; O’Meara, 2010; Jackson et al., 2017; Jiao and Yang, 2021)]. Other species criteria or lines of evidence may also support the idea of an independently evolving lineage. Equating species with historical lineages as identified by genomic data forms the foundation of multispecies coalescent (MSC) delimitation models (Yang and Rannala, 2010; Rannala and Yang, 2020). Recent studies have questioned the relevance of the lineage as the sole criterion for recognizing species, however, and some methods designed to delimit species, e.g. the MSC (Freudenstein et al., 2017; Sukumaran and Knowles, 2017; Sukumaran et al., 2021; Wells et al., 2021), because they may not circumscribe the units we care about. Arguments against lineage-only approaches center around observations that such methods may tend to delimit population structure rather than species and are sensitive to biases in range-wide sampling (Sukumaran and Knowles, 2017; Chambers and Hillis, 2020; Mason et al., 2020; Hillis et al., 2021; Sukumaran et al., 2021). Ignoring aspects of phenotype described as inherent in the ESC by Simpson (1951) [and advocated more recently in de Queiroz (2007) and Freudenstein et al. (2017)] may leave us with units that are little more than historical constructs without meaning to biodiversity.

Over the last two decades, there has been an appreciation of the potential for integrative taxonomy to inform more multifaceted, robust estimates of biodiversity than those based on one-dimensional representations of variation (morphology or genetic sequences alone; Padial and de la Riva, 2010; Padial et al., 2010; Schlick-Steiner et al., 2010; Carstens et al., 2013; Krug et al., 2013; Edwards and Knowles, 2014; Leaché et al., 2014; Solís-Lemus et al., 2015; Cicero et al., 2021; Padial and de la Riva, 2021; Wells et al., 2021). Integrative taxonomy considers multiple data sources, ideally in an evolutionary context, and provides multiple lines of evidence in supporting or failing to support delimitations, including genomics, morphology/anatomy, ultrastructure, development/phenology, behavior, metabolites, and ecological interactions (Fujita et al., 2012; Carstens et al., 2013). A further distinction can be made between iterative and integrative taxonomy, where in the former, datasets are analyzed separately or in a specific order (Padial and de la Riva, 2010; Padial et al., 2010), and in the latter they are analyzed simultaneously in a single framework (Yeates et al., 2011; Edwards and Knowles, 2014; Solís-Lemus et al., 2015; Sukumaran et al., 2021).

Freudenstein et al. (2017) emphasized the co-equal importance of lineage and phenotype in their explication of Simpson’s ESC. Simpson’s use of the term role in his statement of the concept embodied the phenotypic aspect, which Freudenstein et al. (2017) viewed broadly as the extended phenotype (Dawkins, 1982). Role here can be viewed as the interplay between extended phenotype and the evolutionary trajectory of a lineage, the basis of which is the hypothesis of a shift in character states to influence diversification by facilitating novel ecological interactions or roles. Role has a long history, rooted in species concepts that incorporate evolutionary and ecological distinctness (Simpson, 1951; 1961; Van Valen, 1976; Mayr, 1982; 1998; Levin, 2000). Extended phenotype is an intentionally broad category, encompassing any fixed, observable differences among lineages in phenotype, ecological interactions (including symbionts), behavior, reproductive biology, etc., with the requirement that these differences are hypothesized to underlie the evolution of distinct ecological roles and therefore species. How can researchers diagnose role in the practice of species delimitation? Freudenstein et al. (2017) state: “…any fixed change in expressed organismal properties provides evidence for a hypothesis of role shift.” The emphasis on ‘fixed’ organismal properties provides a criterion for assessing patterns of variation among lineages, similar to the empirical concept of ‘diagnosability’ (e.g., Nixon and Wheeler, 1990; Davis and Nixon, 1992), which is broader in that it accepts any fixed difference (such as a codon base change that is synonymous). This view of species has been applied or invoked in a handful of studies (Folk et al., 2017; Sinn, 2017; da Cruz et al., 2018; Zachos, 2018; Ackerfield et al., 2020; Frolov, 2021), but a comprehensive application is lacking.

Some organisms are inherently taxonomically challenging. Parasites, with reduced morphology and genomes, are especially problematic (Molvray et al., 2000; Cameron et al., 2004; Freudenstein et al., 2004; Evans et al., 2008; McNeal et al., 2013; Wicke et al., 2013; Haag et al., 2014). Mycoheterotrophic plants are parasites specializing on and deriving nutrients from their fungal hosts (Leake, 1994; Bidartondo, 2005; Merckx, 2013). Mycoheterotrophs convergently display morphological reductions, lacking leaves or other features that contain character information for species delimitation (Merckx and Freudenstein, 2010; Tsukaya, 2018). They display gene losses (e.g. plastid and nuclear genomes), accelerated substitution rates, and horizontal gene transfer, which complicate phylogenomic analyses (Merckx, 2013; Barrett et al., 2014; Braukmann et al., 2017; Graham et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2018; Barrett et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019). Parasites continue to be difficult to place, having been historically lumped into ‘trash bin’ morphologically-defined taxa, due to convergent losses (morphological and genomic), long branches in phylogenetic analyses, and missing data, requiring novel or specialized analytical approaches (e.g. Philippe et al., 2005; Pagel and Meade, 2008; Darriba et al., 2016; Givnish et al., 2018; Lam et al., 2018; Crotty et al., 2020; Young and Gillung, 2020). An integrative approach to taxonomy is essential for such groups, as it maximizes potential information for their placement, including species delimitation (Barrett et al., 2011; Broe, 2014; Freudenstein and Barrett, 2014).

One problematic group is the Corallorhiza striata complex, a wide-ranging, variable orchid of uncertain status (Fig. 1). This complex has a broad but patchy distribution, is locally rare, has reduced morphology (leaflessness and rootlessness), and displays clinal patterns of morphological variation (Freudenstein, 1997). Recent analyses have recognized three species: Corallorhiza bentleyi, a threatened species restricted to the eastern USA, known from ~12 populations; C. involuta (formerly C. striata var. involuta), a poorly known, disjunct relative of C. bentleyi endemic to Mexico; and C. striata, a wide-ranging, variable species distributed from Mexico to Canada (Freudenstein, 1997; Magrath and Freudenstein, 2002; Barrett and Freudenstein, 2011). Corallorhiza bentleyi and C. involuta share a close relationship yet are divergent from C. striata based on nuclear markers and plastid genomes (Barrett and Freudenstein, 2011; Barrett et al., 2018). Here we focus exclusively on C. striata, within which two varieties have been recognized: var. vreelandii, distributed among sky island forests of Mexico and the southwestern USA, and var. striata, distributed from the northern-US Rocky Mountains into southern Canada (British Columbia to Newfoundland).

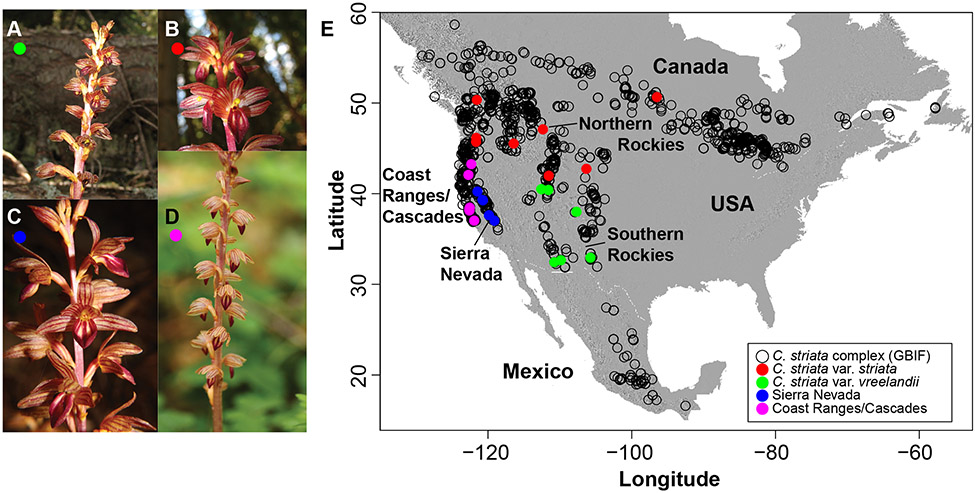

Figure 1.

A. Corallorhiza striata var. vreelandii (green). B. C. striata var. striata (red). C. C. striata from the Sierra Nevada of California, USA (blue). D. C. striata from the Coast Ranges/Cascades of California and Oregon, USA (magenta). E. Map showing the geographic range of the C. striata complex. Black empty circles are GBIF records based on herbarium collections. Colored, filled circles are sampling localities included in the ISSRseq analysis (see Fig. 2) for each of the four groupings in A.

Taxonomic delimitation within C. striata is challenging. Freudenstein (1997) noted clinal patterns of morphological variation across North America, with C. striata var. vreelandii (Fig. 1A) having smaller, less-open flowers, suggesting a reproductive mode of self-pollination. Corallorhiza striata var. striata (Fig. 1B) has large, open flowers, and is pollinated by ichneumonid wasps (Freudenstein, 1997; personal observation). DNA sequences and morphology showed distinctness among them, but with some overlap in morphological features, making field- or herbarium-based identification difficult (Barrett and Freudenstein, 2009; 2011). Adding to the confusion, populations in California, USA (Fig. 1C, D), are morphologically intermediate between the two recognized varieties (Barrett and Freudenstein, 2009; 2011), having been proposed as introgressants by some researchers (e.g. Magrath and Freudenstein, 2002). Plastid genomes revealed that populations sampled from the Sierra Nevada (California) comprise a unique lineage, sister to the clade of vars. striata and vreelandii, within which these two varieties display a pattern of reciprocal monophyly (Barrett and Freudenstein, 2009; 2011). Further, analysis of fungal hosts across North America revealed specificity among the C. striata complex, and particularly among Sierran populations, with this plastid clade exclusively associating with a single clade of ectomycorrhizal fungi within Tomentella fuscocinerea, whereas the two currently recognized varieties associate more broadly with genotypes of the same species (Barrett et al., 2010). Tomentella is a diverse, globally distributed genus of ~80 species of ectomycorrhizal fungi within the family Thelephoraceae, and is often common in forest communities, especially in those dominated by gymnosperms (Larsen, 1974; Jakucs and Erős-Honti, 2008).

To date, few collections from the Coast Ranges of California or the Cascades of Oregon have been studied, calling into question their taxonomic affinities relative to Sierran populations and vars. striata and vreelandii. A recent analysis of plastid genomes included five accessions from the Coast Ranges (California) and Cascades (western Oregon), indicating that these accessions were nested among accessions of C. striata var. striata (Barrett et al., 2018). While plastid DNA is informative and displays accelerated evolutionary rates in C. striata (below the species level), it represents one, uniparentally inherited record of evolutionary history, and is therefore subject to potential confounding effects of ILS and past/present gene flow relative to representations based on a broad sampling of nuclear loci (Willyard et al., 2009; Folk et al., 2017; García et al., 2017; Gernandt et al., 2018; Doyle, 2021; Rose et al., 2021). Further, the Coast Range/Cascade populations have been observed to flower earlier than those in the rest of North America (February-April in the California Coast Ranges vs. May-July elsewhere; Coleman, 2002), possibly representing a temporal barrier to gene flow. Lastly, none of the Coast/Cascades populations have been sampled for fungal associates, calling into question whether they show a similar pattern of specificity as do those in the Sierra Nevada relative to vars. vreelandii and striata.

Here we analyze data from genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms, floral morphometry, phenology, reproductive mode, abiotic niche, and patterns of fungal host specificity to quantify and analyze variation in Corallorhiza striata within the framework of ‘lineage+role.’ The rationale for including each of these datasets is as follows: genomic data can provide a powerful source of evidence for distinct lineages (de Queiroz, 2007; Leaché et al., 2014), whereas phenotypic data can provide the basis for hypotheses of role shifts (sensu Freudenstein et al., 2017). Further, shifts in role may be attributed to changes in reproductive features, forming barriers to gene flow (phenology, selfing vs. outcrossing), or differences in features hypothesized to be driven by variation in abiotic niches. Lastly, mycoheterotrophic orchid lineages are known to have undergone significant host shifts from saprotrophic ‘rhizoctonia,’ the typical associates of photosynthetic orchids, to ectomycorrhizal fungi, and are often highly specific towards their host fungi (e.g. Taylor and Bruns, 1997). This potentially equates to novel and highly specific interactions that have been hypothesized to drive speciation, analogous to the situation in many plant-feeding insects (e.g. Dres & Mallett, 2002; Taylor et al., 2004).

Specifically, we ask: How many species comprise this complex, aside from C. bentleyi and C. involuta? Can an integrative approach to taxonomy shed light on species-level delineation in this complex? How can role be applied in this complex as a defining factor in delimiting species, and what is role here? We conduct the first in-depth analysis and application of ‘ISSRseq’ (Sinn, Simon et al., 2021), an economical, straightforward approach to generating SNP data, and demonstrate that these data are highly informative within the C. striata complex. We hypothesized that morphology, phenology, reproductive mode, and fungal associates may each satisfy role in this complex. Here, we consider a sufficient definition of species boundaries to be one that requires separately evolving lineages (sensu Simpson, 1951; de Queiroz, 2007), with the added requirement of displaying evidence of fixed differences in some aspect of the ‘extended phenotype.’ To our knowledge, this study represents the most comprehensive application of ‘lineage+role’ to date in integrative species delimitation, the implications of which are discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample collection and DNA extraction

Tissues were collected across the USA, Mexico, and western Canada between 2005 and 2017 (1-5 individuals each among 53 localities, 200 individuals total; Table S1). We aimed to maximize broad geographic sampling, focusing on the center of diversity in western North America, but also sampled in putative contact zones in northern Utah and California/Oregon (Fig. 1E). A CTAB protocol was performed to isolate shoot (floral) and rhizome (plant+fungal) DNA (Doyle and Doyle, 1987).

2.2. ISSRseq and SNP analyses

In order to determine evidence for distinct lineages within C. striata, we used a recently published protocol, ISSRseq, as an effective method of reduced-representation sequencing, outlined in Sinn, Simon et al. (2021). Briefly, this method involves PCR amplification and high-throughput sequencing of inter-simple sequence regions (ISSR), amplified with single primers that bind to microsatellites motifs (e.g. Zietkiewicz et al., 1994). Instead of scoring presence/absence of bands as dominant markers, as is traditionally done with ISSR, we conduct library preparations and Illumina sequencing of these regions, resulting in a genomic-scale dataset of codominant SNP markers. ISSR regions were amplified for 87 C. striata individuals from 26 localities with eight primers in single-primer reactions, with a focus on western North America, specifically California. Amplification, library preparation, Illumina sequencing, bioinformatic processing, and the data themselves are described in Sinn, Simon et al. (2021). Biallelic SNPs were filtered using “phrynomics” in R to remove non-binary and non-informative SNPs (Leaché et al., 2015). SNPs were used to infer relationships among individuals with RAxML-NG using 1,000 bootstraps with the best-fit model: GTR+G4m+ASC (Kozlov et al. 2019). Bootstrap support was assessed with 1,000 standard bootstrap pseudoreplicates. Another tree was built using IQtree2 (Nguyen et al., 2015; Minh et al., 2020) with best fit model TVM+F+ASC+R3 as determined by ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017). The ‘ASC’ option accounts for ascertainment bias in SNP-only data (Lewis, 2001; Leaché et al., 2015). Support was assessed with 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap pseudoreplicates (Hoang et al., 2018). A coalescent-based “species tree” was estimated with SVDquartets in PAUP v.4 with 1,000 bootstraps (coalescent model, sampling all quartets, Erik+2 normalization; Swofford, 2003; Chifman and Kubatko, 2014; 2015).

To test among alternative species delimitation scenarios using genomic data alone, Bayes Factor Delimitation (Leaché et al., 2014) was conducted via SNAPP-BFD* in BEAST2 (Bouckaert et al., 2019). Path sampling was conducted via stepping stone analysis (Kass and Raftery, 1995; Baele et al., 2013; Grummer et al., 2014) to obtain maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) under four different scenarios: 1) four species (striata, vreelandii, Coast/Cascades, Sierra), 2) three species (striata, vreelandii, Coast/Cascades+Sierra, 3) three species (striata+vreelandii, Coast/Cascades, Sierra), and 4) two species (striata+vreelandii, Coast/Cascades+Sierra). Due to the computational requirements of SNAPP, we reduced the 83-accession dataset to 26, randomly choosing one per locality. As above, sites were removed in ‘phrynomics’ to reduce the missing data to <5 % (Leaché et al., 2014). We ran 48 ‘steps’ for each of three independent runs for each scenario to check convergence among replicates (30 cores, 512 Gb RAM). Each chain was run for 250,000 generations, with 20% burn-in, after pre-burn-in of 50,000 generations. We verified stationarity and convergence across runs in Tracer v.1.7.1 (Rambaut et al., 2018), requiring effective sample sizes >200. Results were summarized by ranking each model/scenario based on the lowest MLE score, using the formula: BF=2×(MLE1−MLE0), in which model0 had the highest MLE. Bayes Factors < −10 indicate ‘decisive’ support for model0 over model1.

Population structure was characterized using Principal Components Analysis (PCA) in Adegenet v.2.1.5 (Jombart, 2008; Jombart and Ahmed, 2011), after linkage disequilibrium (LD) thinning to one SNP per locus in VCFTOOLS (Danecek et al., 2011); thinning was set to 3kb, greater than the length of the longest assembled contig. Global FST among lineages was assessed with hierfstat (Goudet, 2005). Analysis of admixture was conducted in DyStruct v1.1.0 (Joseph and Pe’er, 2019), with K=1-8, to determine the most likely number of ancestral clusters. Runs were replicated ten times for each K-value, specifying a hold-out of 0.05, starting each replicate from a random seed, and increasing the epochs to 100. MLEs across each value of K were used to calculate ‘Delta K’ to determine the most likely number of clusters (Evanno et al., 2005).

To compare resolution of SNPs and microsatellites from ISSRseq data, we used ‘SSRGenotyper’ (Lewis et al., 2020; https://github.com/dlewis27/SSRgenotyper), which identifies 2-, 3-, and 4-mer motifs with MISA (Beier et al., 2017) from .sam files and a reference sequence, requiring >100 bp of flanking sequence. Cleaned reads were mapped to the de novo reference sequence (see Sinn, Simon et al., 2021 for details) with BWA-MEM (Li and Durbin, 2009), and processed with SAMTOOLS (sorting, removing duplicates, filtering on mapping quality of -q 45). GENEPOP output was read into ‘adegenet’ v.2.1.3 (Jombart, 2008) in R, as was the LD-thinned SNP dataset. We used Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC; Jombart et al., 2010b), choosing the optimal number of PCs to retain via cross-validation and a-score optimization.

2.3. Morphology

To test for morphological distinctness among previously identified lineages, we measured fourteen floral characters for a single flower from each of 127 individual plants (as in Barrett and Freudenstein, 2011) using a stereo microscope (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). All flowers were field-collected and fixed in 10% formalin, 50% ethanol, and 5% glacial acetic acid. Measurements were calibrated to a 2 mm slide and analyzed with Image J v.1.53e (Rueden et al., 2017). PAST v.4.09 software (Hammer et al., 2001) was used to conduct PCA of log10-transformed data with a variance-covariance matrix and Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA). Plots were constructed using ‘ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016) and ‘ggpubr’ v.0.4.0 in R (Kassambara, 2020). We further constructed a ‘phylomorphospace’ with the R package ‘phytools’ v.0.7.47 (Revell, 2012), using the RAxML-NG tree and morphological PC scores.

2.4. Abiotic niche

We used publicly available collections records to test whether var. striata, var. vreelandii, Coast/Cascades, and Sierran populations occupy different abiotic niche space, to explore difference occupancy of niche space constitutes evidence (as a proxy) for shifts in role. All records from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (https://www.gbif.org; accessed 05 January, 2022) were downloaded specifying georeferenced records and preserved specimens with the R package ‘rgbif’ v.3.6.0 (Chamberlain et al., 2022). Occurrences were then filtered for coordinate uncertainty with CoordinateCleaner v.2.0.20 in R (Zizka et al., 2019). Records from US States/Counties, Mexican States, and Canadian Provinces where each of the aforementioned entities are known to be distributed were manually curated and assigned to one of the four groups. When available, digitized images were inspected to verify records. Nineteen BIOCLIM variables (https://worldclim.org) were downloaded at both 10 km and 0.5 km resolutions in R via the ‘raster’ v.3.5.2 package (Hijmans, 2022). The full BIOCLIM dataset was subjected to Principal Components Analysis in Past v.4 (Hammer at al., 2001), specifying a correlation matrix to account for differences in the scale of the variables.

The full BIOCLIM dataset was then subjected to pairwise Pearson correlation analysis using ENMTools v.1.0.5 (Warren et al., 2021), retaining only uncorrelated BIOCLIM variables at a 0.7 threshold. Data were spatially thinned to a minimum distance of 10 km to reduce the effects of autocorrelation with ‘SPthin’ v.0.2.0 in R (Aiello-Lammens et al., 2015). The ‘ecospat’ function (Di Cola et al., 2017) via ENMTools was used to conduct niche identity and niche background/similarity tests in R, using two metrics: Schoener's D (Schoener, 1968) and Warren’s I (Warren et al., 2008). Ecospat identifies available and occupied environmental niche space as an N-dimensional representation via kernel density (Broennimann et al., 2012; Di Cola et al., 2017). We performed pairwise identity tests among each of the four entities, choosing 1,000 background points at 10 km resolution with 999 permutations. The niche identity test generates a null distribution of overlaps and asks whether two entities are drawn from the same distribution. Further, we conducted background/similarity tests, which address expected similarity between groups based on environments available to them, and are more robust to situations of allopatry or parapatry (Warren et al., 2008).

2.5. Phenology and reproductive mode

To investigate reproductive evidence for shifts in role, records from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) were searched to visualize differences in flowering time among var. vreelandii, var. striata, Sierran, and Coast Range/Cascade populations. Only records post-1940 were retained, as those before this time had poorer annotation data and may not reflect current phenologies due to climate change. Flowering is not known to occur after mid-August in C. striata (Freudenstein, 1997), so records up to August 1 were kept. Collection dates were converted to days from January 1 within each year in R with ‘lubridate’ v.1.7.10 (Grolemund and Wickham, 2011). We searched individual records via the SEINet collections database (https://swbiodiversity.org/seinet) to compile information on pollination frequency. Specifically, we quantified the proportion of flowers per specimen that showed evidence of fruiting (large, swollen ovaries). Because populations from the California Coast Ranges typically flower much earlier (late February to mid-March; Coleman, 2002; Coleman et al., 2012), we included specimens collected after April 1 for these populations. One-way Analysis of Variance was used to test for significant differences in flowering time and the proportion of pollinated flowers among the groupings with Tukey comparisons in R.

2.6. Fungal DNA analyses

In order to quantify patterns of specificity and divergence in fungal associations among lineages of C. striata, we extracted DNAs from rhizome tissues (mixed orchid and fungal DNAs) of 11 accessions form the Coast Ranges/Cascades were amplified and sequenced using fungal-specific primers ITS1F/ITS4 (White et al., 1990), following Barrett et al. (2010), and combined with sequence data sampled more broadly in the latter study. Electropherograms edited in Geneious v.10 (Drummond et al., 2011) and further aligned using the MAFFT v.7.490 plugin (‘auto’ algorithm; Katoh and Standley, 2013). In addition, we included >1,400 ITS reference sequences from the fungal family Thelephoraceae (NCBI GenBank), excluding ‘environmental’ sequences, for phylogenetic placement of fungal sequences derived from C. striata. Thelephora terrestris was chosen as an outgroup taxon (NCBI GenBank accession AF272923). Corallorhiza-derived fungal sequences were realigned with reference sequences in MAFFT. Ambiguously aligned regions with >95% gaps or missing data were removed in Geneious. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted with FastTree v.2.1.10 under a GTR model with 1,000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates (Price et al., 2010).

To test for phylogenetic signal in associations among the four groupings (i.e. nonrandom associations), we used the sub-clade from the fungal ITS tree containing all C. striata accessions, pruning reference Tomentella and associates of C. bentleyi+involuta with ‘ape’ v.5.5 in R (Paradis and Schliep, 2019). Associations were coded as a multistate, unordered character corresponding to each grouping. Phylogenetic signal was tested using a randomization test in R, 'phylo.signal.disc' (Bush et al., 2016; https://github.com/juliema/publications/blob/master/BrueeliaMS/Maddison.Slatkin.R), with 999 permutations to generate a null distribution of states on the tree. The script uses ‘ape,’ ‘geiger’ v.2.0.7, ‘phangorn’ v.2.5.5, and ‘phylobase’ v.0.8.10 (Schliep, 2011; Pennell et al., 2014; Bolker et al., 2020; R Hackathon et al., 2020) to compare the null distribution of the number of character state transitions with the observed number on the tree.

2.7. Integrative analyses

Lastly, we conducted integrative analyses of multiple datasets to quantify their contribution to divergence among lineages, and to identify evidence for shifts in role. In order to analyze multiple datasets integratively, population assignment analyses were conducted with the R package ‘assignPOP’ v.1.2.4 (Chen et al., 2018). This software allows simultaneous integration of different data types, including SNP data, morphology, etc., by conducting principal components analysis on each dataset and then using linear discriminant analysis or various machine learning algorithms to estimate population assignments and ancestry coefficients. A proportion of the data is specified to train predictive models using Monte Carlo and K-fold cross-validation. We ran assignPOP for a reduced dataset of 47 accessions, including only accessions for which genomic (LD-thinned SNP data), morphological, abiotic niche, and fungal data were available for each accession, with each lineage representing a population cluster (i.e., K = 4). The fungal ITS subtree containing only C. striata accessions was transformed into Abouheif root-to-tip distances (Abouheif, 1999) in the R package ‘adephylo’ v.1.1.11 (Jombart et al., 2010a). Abouheif distance relies on a phylogenetic proximity matrix, considering the inverse product of all direct descendants of a node, and thus captures the tree topology as opposed to more standard distance metrics. All data were log10-transformed.

Analyses were conducted using the ‘assign.MC’ (MCMC, Markov Chain Monte Carlo) and ‘assign.kfold’ cross-validation algorithms under LDA, support vector machine (SVM), and random forest (RF) algorithms. After testing different trial parameter sets and assignment accuracy with ‘accuracy.plot’, we specified 10% of SNP loci (minor allele frequency of < 0.05), the FST method, retaining the first ten principal components, setting K-fold=5, and running for 100 iterations (MCMC). We repeated each analysis three times with: (1) SNP data, (2) SNP + ‘extended’ data (morphological+abiotic niche+fungal data), and (3) only ‘extended’ data. The rationale was to test whether addition of the latter datasets markedly changed assignment probabilities or ancestry coefficients estimated from SNP data alone.

We also tested species delimitations integratively using Redundancy Analysis (RDA; Rao, 1964; Legendre and Anderson, 1999) in the R package ‘vegan’ v.2.5.7 (Oksanen et al., 2020), to address the hypothesis that ‘extended’ datasets may form the basis for hypotheses of role shifts with respect to the genomic lineages identified. We tested ‘four species’ vs. ‘three species’ delimitations, which in the latter case accessions from the Coast/Cascades and Sierra Nevada were considered a single species. Delimitations were coded as ‘dummy’ variables (0/1; Zapata and Jiménez, 2012; Papakostas et al., 2016; Firneno et al., 2021), and were used as potential explanatory variables in four RDA scenarios with different datasets as the response variables (representing role): (1) morphology only, (2) abiotic niche only, (3) fungal associates only (Abouheif distance, as above), and (4) combined ‘extended’ data (excluding SNP data). We ran RDA and variance partitioning (Peres Neto et al., 2006; Legendre et al., 2011) to quantify the unique and shared contributions among delimitations and test the significance of the adjusted R2 values for each dataset.

3. Results

3.1. ISSRseq and SNP analyses

The final ISSRseq dataset consisted of 27,117 SNPs (dataset S2), 6,589 of which remained after LD-thinning (dataset S3), and 2,662 of which remained after removal of non-parsimony informative sites with ‘phrynomics’ in R (dataset S4). Phylogenetic analyses based on informative SNPs yielded highly resolved and supported topologies (Fig. 2A-C). Relationships among major clades from RAxML-NG, SVDQuartets, and IQtree2 were congruent, with strong bootstrap support for four major groupings: C. striata var. striata, C. striata var. vreelandii, Sierran, and Coast/Cascade accessions. Bootstrap support was >90% for the sister relationships and for the monophyly of each of the four groupings. Topologies from RAxML-NG and IQtree differed slightly within major clades [Robinson-Foulds (RF) symmetric distance = 2], while both topologies differed to a greater degree from the SVDQuartets topology (RF symmetric distance = 74), though these topological differences were largely at mid-levels or towards the tips of the trees. Individuals from the same locality tended to group together in many cases (e.g. var. striata population 187 from Lewis and Clark County, Montana, USA; var. vreelandii population 163 from Ouray County, Colorado, USA; populations 312 and 432 from Santa Cruz County, California, USA; and population 253 from Fresno County, California, USA).

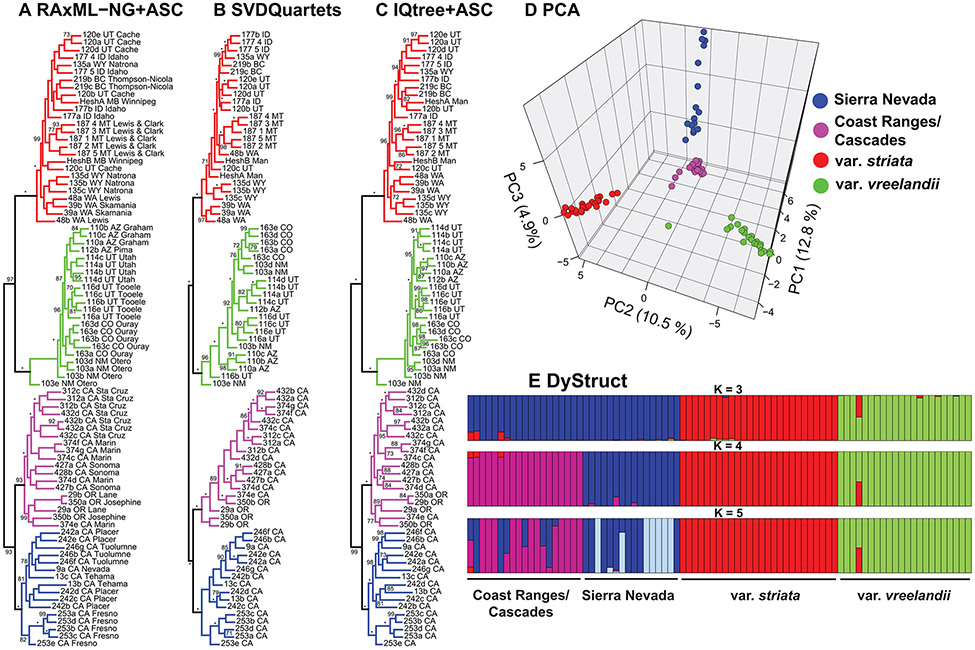

Figure 2.

Relationships and genetic differentiation of the C. striata complex based on SNP data from ISSRseq. A. Relationships based on maximum likelihood analysis in RAxML-NG with an ascertainment bias model. B. Relationships based on analysis in SVDQuartets. Total weight of compatible quartets = 0.927. C. Relationships based on maximum likelihood analysis in IQtree2 with an ascertainment bias model. D. Principal Components Analysis of linkage disequilibrium-thinned SNP data, showing PCs 1-3. E. Population structure analysis in DyStruct for K=2-4. Colors correspond to legend in d).

PCA of LD-thinned ISSRseq data (6,589 SNPs) revealed distinct genomic groupings based on the first three PCs (Fig. 2D), with PC1 differentiating var. striata and vreelandii from the Sierran and Coast/Cascade populations (12.8% of total variance), PC2 differentiating var. vreelandii and striata (10.5%), and PC3 differentiating Sierran and Coast/Cascade populations (4.9%). Overall FST was 0.57 (p < 0.001). Population structure analysis with DyStruct yielded the highest Delta K values of 139.8 and 92.3 for K = 3 and K = 4, respectively (Table S2). For K = 3, there were three distinct groupings corresponding to var. vreelandii, var. striata, and all Californian accessions, while with K = 4, the Californian accessions were distinct between the Sierra Nevada and Coast/Cascades. There is little evidence for admixture among the groupings, except in a few cases, most notably, accession 103e from Otero County, New Mexico, USA, with apparent mixed ancestry between var. vreelandii and var. striata. A few accessions from the Sierra Nevada show at least some proportion of the genome from the Coast/Cascade cluster, while a few accessions of the latter show at least some proportion of the genome from the var. striata cluster.

The SSRgenotyper pipeline recovered 19 polymorphic microsatellite loci from the ISSRseq data (79 alleles total; Dataset S5) after strict filtering. Discriminant analysis of principal components based on microsatellite repeats revealed a similar pattern of differentiation to that based on SNP data (Fig. S1). As in Fig. 2B, PC1 differentiates var. striata, var. vreelandii, and the Californian accessions, PC2 differentiates var. striata from the rest of the groupings, and PC3 differentiates the Sierra Nevadan accessions from the Coast/Cascade accessions. Overall, microsatellites show a somewhat weaker pattern of differentiation relative to that based on SNP data, but recover the same general signal.

Among the four alternative species delimitation models tested with SNAPP-BFD*, the four-species model had the highest MLE and overwhelming support compared to the alternative species delimitation scenarios based on Bayes Factor comparisons (L = −175,646.5; Table 1). Both of the three-species models tested had lower Bayes Factors compared to the four-species model, with BF = −311.8 for treating the Sierran and Coast/Cascade accessions as a single species, and BF = −5,294.8 for treating vars. vreelandii and striata as a single species while keeping the Sierran and Coast/Cascade accessions separate. The two-species model also had lower support than the four-species model, with the former treating vars. vreelandii and striata as a species, while also treating the Sierran and Coast/Cascades accessions as a species (BF = −5,026.6).

Table 1.

Results of SNAPP-BFD* species delimitation analyses. ‘# spp’ = the number of species in a particular scenario, ‘MLE’ = Maximum likelihood estimate for a particular scenario, ‘rank’ = the rank of each scenario based on MLE values, ‘BF’ = Bayes Factor comparison of a particular scenario to that with the lowest MLE value. Under ‘Delimitation,’ ‘str’ = var. striata, ‘vre’ = var. vreelandii, ‘snv’ = Sierra Nevada, and ‘crc’ = Coast Ranges/Cascades.

| # spp | Delimitation | MLE | rank | BF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | (str) (vre) (snv) (crc) | −175646.5 | 1 | -- |

| 3 | (str) (vre) (snv + crc) | −175802.4 | 2 | −311.8 |

| 2 | (str + vre) (snv + crc) | −178159.8 | 3 | −5026.6 |

| 3 | (str + vre) (snv) (crc) | −178293.9 | 4 | −5294.8 |

3.2. Morphology

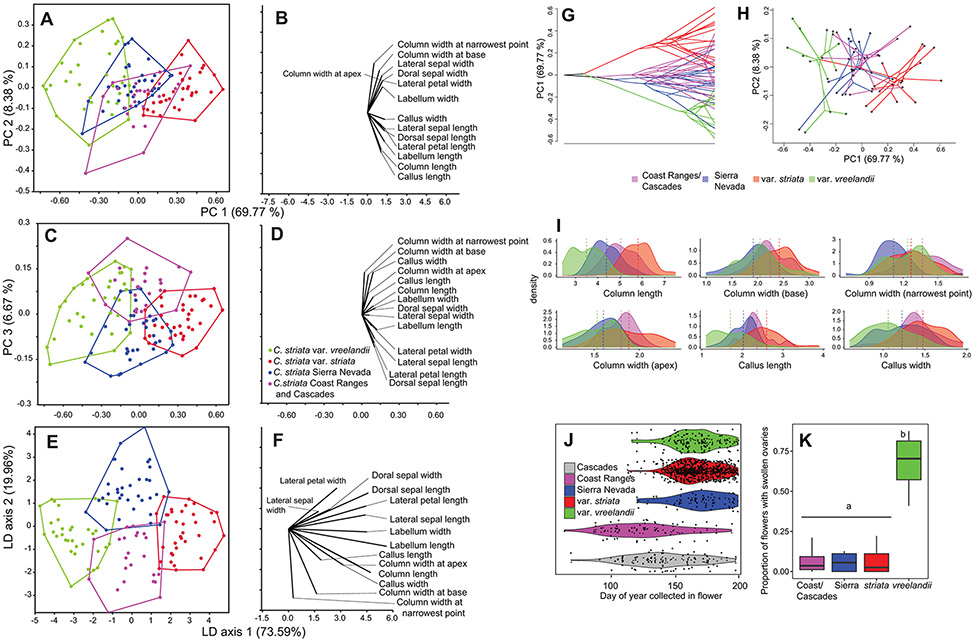

Analysis of 14 floral measurement characters via PCA and LDA revealed somewhat distinct groupings, but with evidence of overlap among them (Fig. 3A, C, E; Dataset S6). Perianth length/width characters were largely correlated with PC1 (69.77% of total variance, e.g. petal, sepal, and labellum characters; Table S3), while characters associated with the column and callus were correlated with PC2. PC1 reflects overall size differences among the larger-flowered var. striata, the small-flowered var. vreelandii, and the intermediate-sized Californian accessions. PC3 partially differentiates Sierran and Coast/Cascade individuals based on column and callus characters, but also to some degree on sepal and petal characters, though this axis only explains a small amount of the total variation (6.67%). LDA/MANOVA reveals statistically significant multivariate differences among all four groupings (Wilks’ lambda = 0.062, p < 0.0001), with significant, Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons among all groupings (Fig. 3E, f; p < 0.0001 in all pairwise comparisons). Further, LDA/MANOVA classified 116 of 127 accessions (91.3%) according to their a priori assignment (Table 2). A phylomorphospace representation, combining the RAxML-NG tree with the PCA for morphology, further illustrates the genomic and morphological distinctness of vars. vreelandii and striata, but also displays overlap among the two Californian entities and vars. striata and vreelandii (Fig. 3G, H). A closer investigation of column and callus characters reveals that column length, column width (at base, narrowest point, and apex), and callus length/width ratio comprise most of the variation among Sierran and Coast/Cascade individuals. However, there is some overlap in the distributions of all of these characters.

Figure 3.

Morphological, phenological, and reproductive mode analyses of the C. striata complex. A. Principal Components Analysis (PCA) of 14 log-transformed floral morphological characters, showing PCs 1-2. B. Biplot showing the loading scores of each character on PCs 1-2. C. PCA of PC axes 1 and 3. D. Biplot of character loadings on PCs 1-3. E. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) of the same data, showing LDA axes 1 and 2. F. Biplot of the morphological characters on LDA axes 1 and 2. G. Phylomorphospace representation of PC scores for PC axis 1, with relationships from the RAxML-NG tree superimposed. H. Two-dimensional phylomorphospace representation with the RAxML-NG tree on PCs 1 and 2. I. Density plots of the six most informative characters differentiating Sierra Nevadan and Coast/Cascade accessions. Scale is in mm. J. Violin plots of specimen records by flowering date. Note that Cascades accessions were split from Coast Range accessions here to investigate differences in flowering time between accessions from these two regions. K. Boxplots of the proportion of flowers in a raceme with clear evidence of swollen ovaries. Letters ‘a’ and ‘b’ are Tukey post-hoc comparison values that are significantly different (p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Confusion matrix from Linear Discriminant Analysis analysis of 14 morphological characters, showing the number of positive classifications based on a priori assignments. Overall, 91.34% of accessions were classified according to their a priori grouping. Rows are the given, a priori groups and columns are the classified groups. The diagonal values (boldface) indicate the numbers of successful classifications to a priori groupings.

| var. striata | var. vreelandii |

Sierra Nevada |

Coast/ Cascades |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| var. striata | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 |

| var. vreelandii | 0 | 29 | 2 | 1 | 32 |

| Sierra Nevada | 3 | 2 | 29 | 1 | 35 |

| Coast/Cascades | 1 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 24 |

| Total | 40 | 32 | 31 | 24 | 127 |

3.3. Abiotic niche

Pairwise Niche Identity tests with Ecospat address the null hypothesis that niche overlap is constant when randomly reallocating the occurrences of both groups among their respective ranges. Among the four groupings, pairwise Niche Identity tests revealed that abiotic niche space was less identical than expected by chance in some comparisons but not others, based on the ‘D’ and ‘I’ statistics (Table 3; Dataset S7). Corallorhiza striata var. striata differed significantly from var. vreelandii and Coast/Cascades, but was not significantly different from Sierra Nevadan populations. Corallorhiza striata var. vreelandii differed from Sierra Nevadan populations, but not those from the Coast Ranges/Cascades, while the Sierran populations differed significantly from the Coast/Cascades populations. Ecospat Background/Similarity Tests further consider information on the geographic availability of environmental niche space. The results revealed that niche similarity was lower than expected by chance in all comparisons, but were overall inconclusive, failing to reject the null hypothesis among any of the comparisons (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ecospat identity and background/similarity tests for 10 km and 0.5 km resolutions. Both the ‘D’ and ‘I’ statistics are shown, and cell values represent identity (ID, left value) and background/similarity (BG, right value) test statistics. *p <0.05, **p < 0.01.

| Comparison |

D, ID/BG, 10 km |

I, ID/BG, 10 km |

D, ID/BG, 0.5 km |

I, ID/BG, 0.5 km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| striata - vreelandii | 0.24**/0.31 | 0.33**/0.40 | 0.28/0.27 | 0.37**/0.37 |

| striata - Sierra Nevada | 0.05/0.04 | 0.09/0.10 | 0.18/0.15 | 0.22/0.10 |

| striata - Coast/Cascades | 0.10**/0.11 | 0.14**/0.13 | 0.23/0.19 | 0.29/0.24 |

| vreelandii - Sierra Nevada | 0.06**/0.05 | 0.23**/0.22 | 0.18/0.15 | 0.57/0.64 |

| vreelandii - Coast/Cascades | 0.37/0.37 | 0.62*/0.62 | 0.31/0.29 | 0.48/0.46 |

| Sierra Nevada - Coast/Cascades | 0.24**/0.22 | 0.41**/0.45 | 0.30/0.29 | 0.53/0.52 |

3.4. Phenology and reproductive mode

Flowering time, obtained from 1,743 herbarium records, differs significantly among the lineages (FANOVA = 72.48, p < 0.0001), with Coast/Cascade individuals having earlier flowering times compared to vars. striata, vreelandii, and Sierran individuals (Fig. 3J; pTukey HSD < 0.0001 for all comparisons; dataset S8). Considering individuals from the Coast Ranges vs. the Cascades separately, those from the California Coast Ranges have a slightly earlier flowering time on average than those from the Cascades (pTukey HSD < 0.001). Individuals of var. vreelandii show a higher proportion of swollen ovaries in herbarium records (n = 43 after data filtering; Fig. 3K; dataset S9) than var. striata and Californian individuals (FANOVA = 107.6, p < 0.0001; pTukey HSD < 0.0001 for all var. vreelandii comparisons), but the other three entities do not vary significantly.

3.5. Fungal DNA analyses

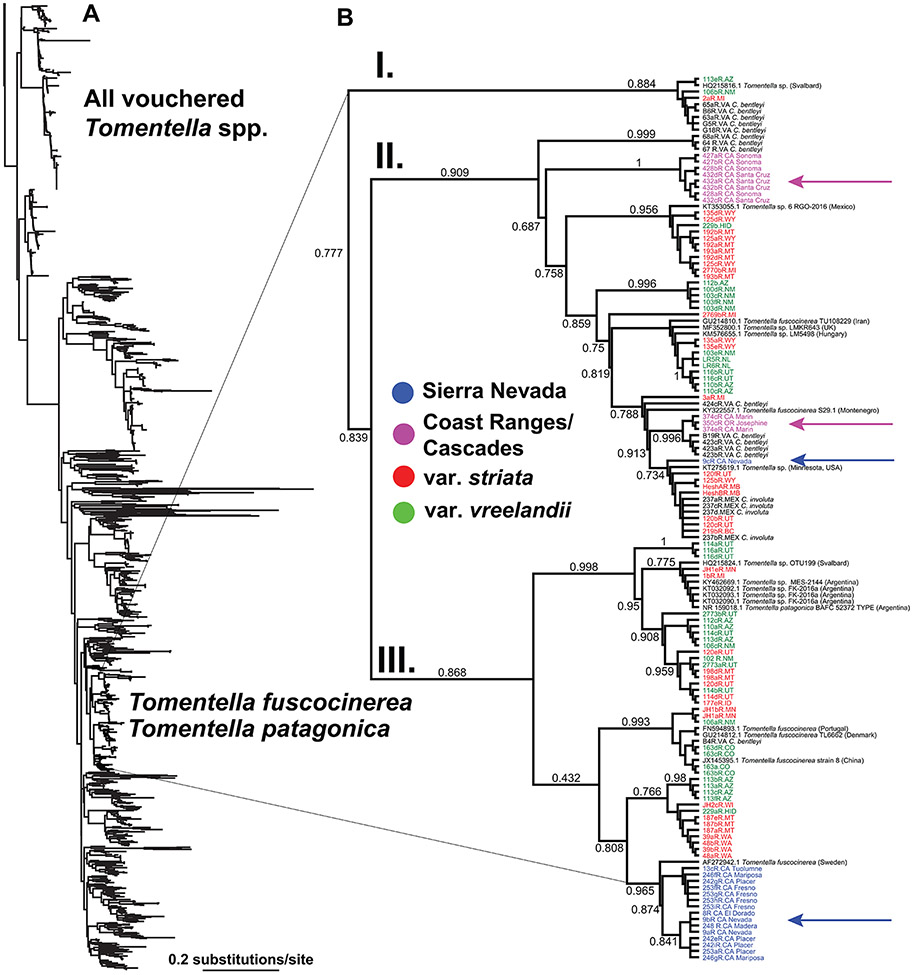

The final fungal ITS alignment (130 sequences from the C. striata complex + 1,451 Tomentella from GenBank), had a total, post-filtered length of 521 bp, with 139 parsimony informative sites (dataset S10). Analysis of C. striata fungal associates confirms a high level of specificity on a single clade of ectomycorrhizal Tomentella, corresponding to all reference sequences of T. fuscocinerea and T. patagonica (Fig. 4A). Within the fungal clade of C. striata associates, Sierran individuals predominantly associate with a single sub-clade (‘Clade III,’ comprising reference accessions of T. fuscocinerea and T. patagonica; πsierra = 0.010), while Coast/Cascade individuals associate largely with members of ‘clade II,’ representing accessions of T. fuscocinerea (πcoast/cascades = 0.030; Fig. 4B; Table S4). The closest relative to associates of the Sierran individuals is from Sweden, while the closest references to associates from the Coast/Cascades are from Minnesota (USA), Hungary, Iran, Mexico, Montenegro, and the U.K. (Fig. 4B). However, a single associate from the Sierra Nevada (9bR, Nevada County, California, USA) groups instead in ‘Clade II,’ while three associates from Marin County, California, and Josephine County, Oregon, USA are divergent from the remaining Coast/Cascade accession within ‘Clade II.’ Associates of vars. striata and vreelandii are widely dispersed throughout the tree, occupying Clades I-III (πvreelandii = 0.029, πstriata = 0.032). However, there is evident clustering of associates for each grouping and phylogenetic signal among associates with each of the four major groupings based on analysis with ‘phylo.signal.disc’ (Fig. S2; p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

A. Phylogenetic analysis of >1,400 Tomentella fungal accessions, including GenBank reference sequences and members of the C. striata complex. Scale bar = 0.2 substitutions/site. B. Closeup of the clade occupied by all accessions of the C. striata complex, with closely related reference sequences from Tomentella fuscocinerea and T. patagonia. Branch lengths are scaled proportionally. Blue and magenta arrows point to associates of the Sierra Nevadan C. striata and the Coast/Cascade C. striata, respectively. Roman numerals indicate three principal sub-clades.

3.6. Integrative analyses

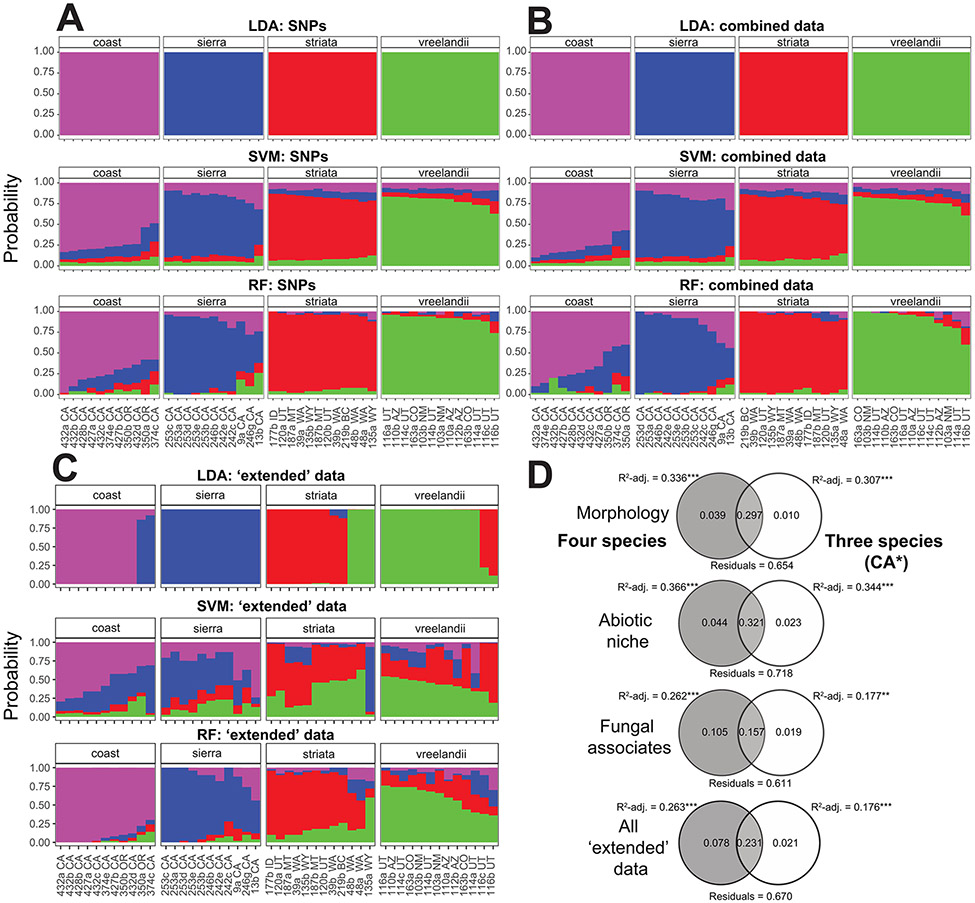

Results from assignPOP were congruent with other clustering methods (Fig. 5). Analysis of SNP-only data revealed a strong pattern of differentiation for LDA, SVM, and RF (Fig. 5A), with posterior probabilities of assignments = 1.0 in all cases (Table S5). Overall, the addition of morphological, abiotic niche, and fungal data did not change any of the analyses (with the exception of the combined data RF analysis for Coast/Cascades and Sierra Nevadan accessions, assignment probability = 0.88; Table S5), suggesting that these data, in combination, hold a similar signal of differentiation and do not controvert the patterns based on SNP-only data (Fig. 5B; Table S5). Analyses of the ‘extended data’ (i.e., including all but the SNP data) recovered similar overall patterns, but with an evidently weaker ability to discriminate the four lineages (Fig. 5C; Table S5). Variance partitioning via RDA, with three- and four-species hypotheses as explanatory variables, showed a preference for a four-species model for all ‘extended’ datasets individually and in combination (Fig. 5D). The models were significant in all comparisons (based on R2-adjusted values, p < 0.01 in all cases; Fig. 5D), but with the four-species model explaining a higher proportion of the overall variance.

Figure 5.

Integrative analyses of SNP and ‘extended’ data. A. SNPs only analyzed in assignPop. B. Combined SNP and ‘extended’ data (morphology, biotic niche, and fungal hosts). C. ‘Extended’ data only. ‘LDA’ = linear discriminant analysis; ‘SVM’ = support vector machine; ‘RF’ = random forest. D. Redundancy Analysis (RDA) and variance partitioning using four- and three-species delimitations as explanatory variables with ‘extended’ data as response variables (* = Corallorhiza striata var. striata, C. striata var. vreelandii, Sierra Nevada + Coast/Cascades).

4. Discussion

4.1. Distinct lineages and integrative taxonomy in C. striata

We analyzed multiple datasets in an integrative approach to species delimitation of the C. striata complex. The most significant finding is the existence of four distinct lineages within this widespread species complex. Further, populations from the Coast Ranges/Cascades of California and Oregon, USA, not previously included in studies of C. striata, comprise a distinct lineage within C. striata, sister to a lineage restricted to the Sierra Nevada in California. Our objective was to balance broad geographic sampling with a focus on contact zones among putative lineages (Fig. 1). Recent studies have emphasized the importance of sampling in contact zones to avoid biases by artificially ‘discretizing’ patterns of variation by lack of sampling (Chambers and Hillis, 2020; Mason et al., 2020; Hillis et al., 2021). To the extent we were able to sample in two putative contact zones (northern Utah and northern California/southern Oregon), we find no evidence for introgression in these regions (Fig. 2D). Instead, we find sharp transitions, indicating distinct lineage boundaries, even for populations sampled within 200 km. The only notable individual of mixed ancestry is from Otero County, New Mexico, USA, but this is far from any putative contact zone, and long-distance dispersal cannot be ruled out (Fig. 2D, E). Additional sampling of contact zones, coupled with analyses based on nuclear SNPs and other data (Derryberry et al., 2014) would be beneficial in testing lineage distinctness. This may be challenging in the C. striata complex, occupying rare, clustered habitats in montane areas surrounded by unsuitable or anthropogenically altered habitats.

4.2. Applying role to lineages of C. striata

What constitutes role in the C. striata complex? Clearly floral morphology, phenology, and reproductive mode are viable candidates, and could be related if differences among the groupings in floral morphometry are adaptive in pollinator specificity as in many other orchid species (Ackerman, 1983; Van Der Cingel, 2001; Sletvold et al., 2010; van der Kooi et al., 2021). However, so little is known about the pollination biology in this species complex that it is impossible to say at this point, requiring careful future observation and analysis of pollinators and floral morphometry across the broad geographic range of this complex.

The predominant mode of self-pollination hypothesized for C. striata var. vreelandii could have implications for role, in the sense of shifting away from insect pollination (Darwin, 1876; Ornduff, 1969; Richards, 1986; Sicard and Lenhard, 2011). In fact, vars. striata and vreelandii appear to be the most morphologically divergent members (Fig. 3A-I), with var. striata (large, open flowers; Fig. 1B) showing evidence of outcrossing and var. vreelandii showing evidence of self-pollination (drab, less-open, smaller flowers; Fig. 1A; Freudenstein, 1997). Floral morphology in these two varieties is influenced by pollination mode, which may play a role in that these two lineages may be reproductively isolated, with floral morphology serving as a proxy for this shift in role. However, there are no clear, fixed differences in morphology (viz. non-overlapping floral character values) or reproductive mode other than overall size differences in the features measured, and thus we cannot conclude that there has been a role shift. Further, the intermediate morphological variation observed in both the Sierran and Coast/Cascade lineages casts doubt on whether there is sufficient evidence to recognize separate species based on morphology and reproductive mode. Earlier flowering time of the Coast/Cascade populations could represent a temporal reproductive barrier to gene flow among this and other lineages of C. striata. But again, a statistically significant difference in phenology does not equate to a fixed difference, such as is seen in the spring-flowering Corallorhiza wisteriana and the fall-flowering C. odontorhiza in northern North America, which are sister species (Freudenstein, 1992; 1997; Freudenstein and Barrett, 2014).

Although the abiotic niche cannot be considered part of the extended phenotype per se, it can be an agent of divergent selective pressure, modulating adaptations, and serving as a proxy for underlying genetic conditions (e.g. Cicero et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2021). Niche identity tests were significant in some cases, indicating less identity than expected by chance among lineages (Table 3), but only at 10 km resolution and not when considering niche data at finer scales (0.5 km resolution). Such tests should be interpreted with caution, however, especially if two lineages being compared are allopatric, in that the habitat of one may not be available to the other, thus making an unfair comparison (Warren, 2008; Cardillo and Warren, 2016; Warren et al., 2021). The background/similarity test attempts to account for this, being more robust in cases of allopatry. However, results of our background/similarity tests were inconclusive at both spatial resolutions (less similarity than expected by chance, but non-significant in all comparisons; Table 3), which we interpret as a lack of decisive evidence for abiotic niche differences playing a clearly defined role in the speciation process.

Lastly, fungal host associations could play a role in speciation, in the contexts of coevolution and diversification by host-switching (Taylor et al., 2002; Waterman and Bidartondo, 2008; Taylor et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2021). Phylogenetic analysis of fungal hosts reveals high specificity, especially considering the predominant associations of Sierran and Coast/Cascade accessions with different fungal clades, with strong phylogenetic signal (Figs. 4b; S2; Barrett et al., 2010). However, the overall pattern of associations within C. striata reveals overlap among the four lineages, especially between vars. vreelandii and striata, and does not fit the hypothesized pattern of non-overlapping associations expected if these orchid lineages had fully co-diversified on their host fungi (Bidartondo and Bruns, 2001; Waterman and Bidartondo, 2008). Instead we interpret this pattern as strong but non-exclusive host preferences among lineages of C. striata towards different genotypes of Tomentella, potentially following a geographic mosaic pattern of specificity (sensu Thompson 1994; 2005; Barrett et al., 2010). One explanation for this pattern could be that ancestral polymorphisms in host associations are not yet fixed among the four lineages of C. striata, if we assume genetic control. Another could be strictly due to geography, in that certain Tomentella genotypes may be more regionally abundant, and that our sampling simply recapitulates this. Though collections of T. fuscocinerea and T. patagonia specimens are few (five records for North America; https://gbif.org), their global distribution suggests these fungal taxa are ubiquitous but locally rare or patchily distributed among forested habitats (Larsen, 1965; 1974; Jakucs and Erős-Honti, 2008; Kuhar et al., 2016). Seed burial experiments among sites with known divergent orchid and fungal associates may shed light on what controls this pattern of specificity (Rasmussen and Whigham, 1993; McCormick et al., 2012).

Mycoheterotrophic specificity in orchids and other clades has been studied extensively, and within the orchids, studies reveal frequent major host switches from typical saprotrophic “rhizoctonia” hosts to ectomycorrhizal hosts (Leake, 1994; Taylor et al., 2002; 2013). These switches to ectomycorrizal hosts most often occur with a significant narrowing of host specificity, in many cases where plant species specifically target specific fungal families, genera, species, or even genotypes. Thus, fungal host specificity is hypothesized to be highly informative as a potential marker of species boundaries for the plants engaged in these parasitic symbioses, and further, these associations may play a role in the speciation process (Hynson and Bruns, 2010; Taylor et al., 2004; 2013). If divergent host associations among lineages somehow disrupt gene flow, then the role of host specificity is clear, as was suggested in the Corallorhiza maculata and odontorhiza-wisteriana complexes (Taylor and Bruns, 1997; Taylor et al., 2004; Freudenstein and Barrett, 2014). If host associations are genetically controlled, we would expect fixed polymorphisms co-adapted for fungal hosts to be frequent throughout the genome, and in LD within lineages associated with fungal host genotypes (Taylor et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2013). Host associations could be indicators and drivers of shifts in role. Our observation of strong host preferences but some degree of overlap in associations suggests at least at the level of the four C. striata lineages, that these associations do not satisfy the strict definition of role, which emphasizes fixation (Fig. 4B; Freudenstein et al., 2017). However, finer-scale analyses of fixed differences and fungal specificity may reveal that role is in fact satisfied, if divergence in associations extends below the level of lineage, and instead represents specific orchid-fungal genotype-genotype specificity or ‘host races’ (sensu Taylor et al., 2004). Denser sampling, specifically targeted in geographically proximal, putative contact zones, may shed light on specificity in associations, which may not be detectable at range-wide scales.

The strongest case for recognizing species under lineage + role would be genomically distinct lineages, each supported by multiple, fixed traits hypothesized to be ecologically important underlying a role shift (though one fixed trait would be sufficient; Freudenstein et al., 2017). Examples might include different features of feeding apparatus associated with plant hosts, differences in reproductive structures that serve as premating barriers, or adaptations to different abiotic habitats. What if there are no obvious, detectable, fixed differences in any single extended phenotype trait among lineages, but many traits analyzed together, even from different datasets, show clear, emergent patterns of differentiation? Recognizing “clusters in phenotypic [or other] space” as species is best described as a phenetic approach (Sokal and Sneath, 1963; Michener, 1970; Sokal and Crovello, 1970; Sneath and Sokal, 1973). While phenetics is widely applied at the species level, many have criticized this approach as lacking evolutionary context (Hull, 1988; Donoghue, 1990; de Queiroz and Good, 1997). On one hand, if those features measured, even if not fixed for any single character, are synergistically linked (e.g. morphometric variation in tooth and jaw morphology associated with different food preference, canalized differences in floral dimensions associated with different frequencies of pollinator types), then one could hypothesize that there is an ecologically important role shift (Lockwood, 2007). Combined with lineage evidence, one could justify recognition of separate species, each occupying distinct “hyper-roles,” without detectable, fixed differences in any one feature. On the other hand, the problem of arbitrariness persists: where does one objectively draw the line that determines species boundaries in multivariate (or any single continuous character) space?

Some researchers may view the interpretation of our results—a lack of sufficient evidence for separate species, requiring fixed differences in expressed organismal features—as overly conservative. An alternative interpretation might be that the similar patterns of divergence observed among the extended data and lineages, or simply the recovery of distinct lineages themselves, is sufficient evidence for recognizing separate species. For example, some may be comfortable calling the different lineages species under the General Lineage or Unified Species Concept (sensu de Queiroz, 1998, 2005; 2007), secondarily applying phenetic (i.e. morphology) and phylogenetic species concepts (i.e. monophyly). Further, under another interpretation of the Phylogenetic Species Concept (i.e. diagnosability, sensu Nixon and Wheeler, 1990), a single molecular synapomorphy, or suite of SNPs fixed for each lineage, would be sufficient evidence of separate species even without phenotypic evidence of fixation. However, applying this approach to genomic data introduces another level of ambiguity and subjectivity: how does one select the level at which to recognize species, given that there may be fixed synapomorphies at different hierarchical levels in any given dataset? We argue that such interpretations would bring us no closer to objectivity, and instead perpetuate some long-standing problems with species delimitation: a lack of repeatable and consistent criteria, and ignoring the role of species in their environments in favor of relying entirely upon genetic data.

5. CONCLUSION

Here we have taken an integrative approach to species delimitation in the Corallorhiza striata complex, employing seven datasets, requiring distinct lineages and fixed differences in features of the extended phenotype as the basis for species recognition. We identified four genomic lineages based on nuclear data, with evidence for divergent roles based on morphology, phenology, reproductive mode, and fungal hosts. However, none of the metrics of extended phenotype (i.e. proxies for role shifts) satisfy the requirement of fixation, and thus we conservatively conclude that there is insufficient evidence for the recognition of distinct species within C. striata. Taken together, from the standpoints of biodiversity and functional ecology, our findings reveal that recognizing four distinct lineages here at the species level could equate to taxonomic ‘over-splitting,’ and that these lineages are more appropriately recognized as varieties. Our findings provide support for a previous hypothesis that these lineages represent evolutionarily significant units that may warrant more nuanced conservation approaches (Barrett and Freudenstein, 2011). Future studies should emphasize explicit sampling in zones of potential contact among lineages for all of the above metrics, and in particular, reciprocal seed-baiting experiments may prove to be informative on the nature of orchid-fungal specificity, the heritability of these associations, and potential fitness implications. Finally, the current study illustrates the importance of including the concept of role in integrative species delimitation beyond the recognition of historical lineages, which has important implications for biodiversity assessment.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components in ‘adegenet.’ A. Analysis of SNP data from ISSRseq, axes 1 and 2. B. Analysis of SNP data from ISSRseq, axes 1 and 3. C. Analysis of microsatellite data from ISSRseq, axes 1 and 2. D. Analysis of microsatellite data from ISSRseq, axes 1 and 2.

Figure S2. Results from 'phylo.signal.disc' analysis of phylogenetic signal among groupings for fungal associates of C. striata. A. Null distribution of traits (groupings) based on random permutations of states on the fungal ITS tree. X-axis = the number of randomized character state transitions in the null distribution; Y-axis = the frequency of each number of transitions. Red arrow = the number of observed transitions. B. Observed distribution of character states (i.e. groupings) on the fungal ITS tree.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding was provided by the US National Science Foundation awards DEB CAREER 2044259 and OIA 1920858 to CFB; the West Virginia University Department of Biology and Eberly College; a NASA Space Grant to MVS; and by the West Virginia Research Challenge Fund through a grant from the Division of Science and Research, HEPC and in part by (i) the WVU Provost’s Office, (ii) the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences, (iii) the Honors College and (iv) the Department of Biology to MVS and NMF. We are grateful to the USDA Forest Service (FS-2400-1) and California State Parks (DPR65) for permission to collect plant tissues, and to Stephen DiFazio, Jun Fan, Ryan Percifield, and Donald Primerano for sequencing support and discussion. We thank the WVU Genomics Core Facility for support provided to help make this publication possible and CTSI Grant #U54 GM104942 which in turn provides financial support to the WVU Core Facility. We further acknowledge WV-INBRE (P20GM103434), a COBRE ACCORD grant (1P20GM121299), and a West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute (WV-CTSI) grant (2U54GM104942) in supporting the Marshall University Genomics Core (Research Citation: Marshall University Genomics Core Facility, RRID:SCR_018885).

8. DATA ACCESSIBILITY

Sequences of the fungal ITS region are available via NCBI GenBank accession numbers GU224038-GU220711 and OM282086-OM282096. Genomic data from ISSRseq are available via the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (BioProject PRJNA771539). Morphological, genomic (SNP), phenological, abiotic niche, reproductive mode, and fungal ITS data are available as supplementary materials via Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6341174). Code for bioinformatic processing of ISSRseq data is available at GitHub (www.github.com/btsinn/ISSRseq).

7. REFERENCES

- Abouheif E (1999). A method for testing the assumption of phylogenetic independence in comparative data. Evolutionary Ecology Research, 1, 895–909. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerfield JR, Keil DJ, Hodgson WC, Simmons Mark. P., Fehlberg SD, & Funk VA (2020). Thistle be a mess: Untangling the taxonomy of Cirsium (Cardueae: Compositae) in North America. Journal of Systematics and Evolution, 58(6), 881–912. 10.1111/jse.12692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman JD (1983). Specificity and mutual dependency of the orchid-euglossine bee interaction. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 20(3), 301–314. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1983.tb01878.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello-Lammens ME, Boria RA, Radosavljevic A, Vilela B, & Anderson RP (2015). spThin: An R package for spatial thinning of species occurrence records for use in ecological niche models. Ecography, 38(5), 541–545. 10.1111/ecog.01132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baele G, Li WLS, Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, & Lemey P (2013). Accurate model selection of relaxed molecular clocks in Bayesian phylogenetics. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30(2), 239–243. 10.1093/molbev/mss243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CF, & Freudenstein JV (2009). Patterns of morphological and plastid DNA variation in the Corallorhiza striata species complex (Orchidaceae). Systematic Botany, 34(3), 496–504. doi: 10.1600/036364409789271245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CF, & Freudenstein JV (2011). An integrative approach to delimiting species in a rare but widespread mycoheterotrophic orchid. Molecular Ecology, 20(13), 2771–2786. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CF, Freudenstein JV, Lee Taylor D, & Kõljalg U (2010). Rangewide analysis of fungal associations in the fully mycoheterotrophic Corallorhiza striata complex (Orchidaceae) reveals extreme specificity on ectomycorrhizal Tomentella (Thelephoraceae) across North America. American Journal of Botany, 97(4), 628–643. 10.3732/ajb.0900230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CF, Freudenstein JV, Li J, Mayfield-Jones DR, Perez L, Pires JC, & Santos C (2014). Investigating the path of plastid genome degradation in an early-transitional clade of heterotrophic orchids, and implications for heterotrophic angiosperms. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 31(12), 3095–3112. 10.1093/molbev/msu252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CF, Sinn BT, & Kennedy AH (2019). Unprecedented parallel photosynthetic losses in a heterotrophic orchid genus. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 36(9), 1884–1901. 10.1093/molbev/msz111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CF, Wicke S, & Sass C (2018). Dense infraspecific sampling reveals rapid and independent trajectories of plastome degradation in a heterotrophic orchid complex. The New Phytologist, 218(3), 1192–1204. 10.1111/nph.15072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier S, Thiel T, Münch T, Scholz U, & Mascher M (2017). MISA-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics, 33(16), 2583–2585. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidartondo MI (2005). The evolutionary ecology of myco-heterotrophy. New Phytologist, 167(2), 335–352. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidartondo MI, & Bruns TD (2001). Extreme specificity in epiparasitic Monotropoideae (Ericaceae): Widespread phylogenetic and geographical structure. Molecular Ecology, 10(9), 2285–2295. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01358.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolker R, Butler M, Cowan P, Vienne D. de, Eddelbuettel D, Holder M, Jombart T, Kembel S, Michonneau F, Orme D, O’Meara B, Paradis E, Regetz J, & Zwickl D (2020). phylobase: Base Package for Phylogenetic Structures and Comparative Data (0.8.10). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=phylobase [Google Scholar]

- Bouckaert R, Vaughan TG, Barido-Sottani J, Duchêne S, Fourment M, Gavryushkina A, Heled J, Jones G, Kühnert D, Maio ND, Matschiner M, Mendes FK, Müller NF, Ogilvie HA, du Plessis L, Popinga A, Rambaut A, Rasmussen D, Siveroni I, … Drummond AJ (2019). BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLOS Computational Biology, 15(4), e1006650. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braukmann TWA, Broe MB, Stefanović S, & Freudenstein JV (2017). On the brink: The highly reduced plastomes of nonphotosynthetic Ericaceae. New Phytologist, 216(1), 254–266. 10.1111/nph.14681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broe M (2014). Phylogenetics of the Monotropoideae (Ericaceae) with special focus on the genus Hypopitys Hill, together with a novel approach to phylogenetic inference using lattice theory. Undefined. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Phylogenetics-of-the-Monotropoideae-(Ericaceae)-on-Broe/8f2b05a8f9b268d18a5b221f1a4c11d881905a08 [Google Scholar]

- Broennimann O, Fitzpatrick MC, Pearman PB, Petitpierre B, Pellissier L, Yoccoz NG, et al. (2012). Measuring ecological niche overlap from occurrence and spatial environmental data. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 21(4), 481–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00698.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bush SE, Weckstein JD, Gustafsson DR, Allen J, DiBlasi E, Shreve SM, Boldt R, Skeen HR, & Johnson KP (2016). Unlocking the black box of feather louse diversity: A molecular phylogeny of the hyper-diverse genus Brueelia. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 94, 737–751. 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo A, & Sites JJ (2013). Species delimitation: a decade after the renaissance. In: The Species Problem—Ongoing Issues. IntechOpen. 10.5772/52664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron KM (2004). Utility of plastid psaB gene sequences for investigating intrafamilial relationships within Orchidaceae. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 31(3), 1157–1180. 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardillo M, & Warren D (2016). Analysing patterns of spatial and niche overlap among species at multiple resolutions: Spatial and niche overlap. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 25. 10.1111/geb.12455 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens BC & Knowles LL (2007). Estimating species phylogeny from gene-tree probabilities despite incomplete lineage sorting: an example from Melanoplus grasshoppers. Systematic Biology, 56, 400–411. 10.1080/10635150701405560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens BC, Pelletier TA, Reid NM, & Satler JD (2013). How to fail at species delimitation. Molecular Ecology, 22(17), 4369–4383. 10.1111/mec.12413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain S, Barve V, Mcglinn D, Oldoni D, Desmet P, Geffert L, Ram K (2022). rgbif: interface to the global biodiversity information facility API. R package version 3.5.2, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgbif [Google Scholar]

- Chambers EA, & Hillis DM (2020). The multispecies coalescent over-splits species in the case of geographically widespread taxa. Systematic Biology, 69(1), 184–193. 10.1093/sysbio/syz042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K-Y, Marschall EA, Sovic MG, Fries AC, Gibbs HL, & Ludsin SA (2018). assignPOP: An R package for population assignment using genetic, non-genetic, or integrated data in a machine-learning framework. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(2), 439–446. 10.1111/2041-210X.12897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chifman J, & Kubatko L (2014). Quartet Inference from SNP Data Under the Coalescent Model. Bioinformatics, 30(23), 3317–3324. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chifman J, & Kubatko L (2015). Identifiability of the unrooted species tree topology under the coalescent model with time-reversible substitution processes, site-specific rate variation, and invariable sites. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 374, 35–47. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero C, Mason NA, Jiménez RA, Wait DR, Wang-Claypool CY, & Bowie RCK (2021). Integrative taxonomy and geographic sampling underlie successful species delimitation. Ornithology, 138(2), ukab009. 10.1093/ornithology/ukab009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RA (2002). The Wild Orchids of California. Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RA, Wilken DH, & Jennings WF (2012). Orchidaceae. In: Baldwin BG, Goldman D, Keil DJ, Patterson R, Rosatti TJ, & Wilken D (Eds.). The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, 2nd Edition. University of California Press, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty SM, Minh BQ, Bean NG, Holland BR, Tuke J, Jermiin LS, & Haeseler AV (2020). GHOST: recovering historical signal from heterotachously evolved sequence alignments. Systematic Biology, 69(2), 249–264. 10.1093/sysbio/syz051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Cruz de O. R. M, & Weksler M (2018). Impact of tree priors in species delimitation and phylogenetics of the genus Oligoryzomys (Rodentia: Cricetidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 119, 1–12. 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, Handsaker RE, Lunter G, Marth GT, Sherry ST, McVean G, Durbin R, & 1000 Genomes Project Analysis Group. (2011). The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics, 27(15), 2156–2158. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Weiß M, & Stamatakis A (2016). Prediction of missing sequences and branch lengths in phylogenomic data. Bioinformatics, 32(9), 1331–1337. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JI, & Nixon KC (1992). Populations, genetic variation, and the delimitation of phylogenetic species. Systematic Biology, 41(4), 421–435. 10.2307/2992584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins R (1982). The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- de Queiroz Kevin (1998). The general lineage concept of species, species criteria, and the process of speciation. In Howard DJ & Berlocher SH (eds.), Endless Forms: Species and Speciation. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- de Queiroz K (2005). Different species problems and their resolution. BioEssays, 27(12), 1263–1269. 10.1002/bies.20325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Queiroz K (2007). Species Concepts and Species Delimitation. Systematic Biology, 56(6), 879–886. 10.1080/10635150701701083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Queiroz K, & Good DA (1997). Phenetic Clustering in Biology: A Critique. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 72(1), 3–30. 10.1086/419656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C (1876). The effects of cross and self-fertilization in the vegetable kingdom. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry EP, Derryberry GE, Maley JM, & Brumfield RT (2014). hzar: Hybrid zone analysis using an R software package. Molecular Ecology Resources, 14(3), 652–663. 10.1111/1755-0998.12209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cola V, Broennimann O, Petitpierre B, Breiner FT, D’Amen M, Randin C, Engler R, Pottier J, Pio D, Dubuis A, Pellissier L, Mateo RG, Hordijk W, Salamin N, & Guisan A (2017). ecospat: An R package to support spatial analyses and modeling of species niches and distributions. Ecography, 40(6), 774–787. 10.1111/ecog.02671 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky T (1950). Mendelian populations and their evolution. American Naturalist, 84, 401–418. [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue MJ (1985). A critique of the biological species concept and recommendations for a phylogenetic alternative. Bryologist, 88, 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue MJ (1990). Sociology, selection, and success: A critique of David Hull's analysis of science and systematics. Biology and Philosophy, 5(4), 459–472. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ (2021). Defining coalescent genes: theory meets practice in organelle phylogenomics. Systematic Biology, 71(2), 476–489. 10.1093/sysbio/syab053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, & Doyle JL (1987). A Rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin, 19: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DL, & Knowles LL (2014). Species detection and individual assignment in species delimitation: Can integrative data increase efficacy? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1777), 20132765. 10.1098/rspb.2013.2765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]