Abstract

Valine-citrulline is a protease-cleavable linker commonly used in many drug delivery systems, including antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) for cancer therapy. However, its suboptimal in vivo stability can cause various adverse effects such as neutropenia and hepatotoxicity, leading to dose delays or treatment discontinuation. Here, we report that glutamic acid-glycine-citrulline (EGCit) linkers have the potential to solve this clinical issue without compromising the ability of traceless drug release and ADC therapeutic efficacy. We demonstrate that our EGCit ADC resists neutrophil protease-mediated degradation and spares differentiating human neutrophils. Notably, our anti-HER2 ADC show almost no sign of blood and liver toxicity in healthy mice at 80 mg kg–1. In contrast, at the same dose level, the FDA-approved anti-HER2 ADCs Kadcyla® and Enhertu® show increased levels of serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase and morphological changes in liver tissues. Our EGCit conjugates also exert greater antitumor efficacy in multiple xenograft tumor models compared to Kadcyla® and Enhertu®. This linker technology could substantially broaden the therapeutic windows of ADCs and other drug delivery agents, providing clinical options with improved efficacy and safety.

Introduction

Targeted drug delivery has attracted increasing attention as a means to improve drug efficacy while reducing toxicity to healthy tissues. In particular, antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) linked with pharmacologically active molecules (payloads) via chemical linkers, are one of the most promising classes with remarkable and durable treatment effects; they have been used for the treatment of cancers(1,2) and other diseases(3,4). The clinical success of this drug class has been demonstrated with 12 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved ADCs for a broad range of hematological malignancies and solid tumors(5) and more than 100 candidates in clinical trials (clinicaltrials.gov). Despite recent advances in ADC chemistry, medical oncology, and clinical management, ADC-based treatment often entails various side effects, including myelosuppression and liver toxicity. Thus, ADC technologies capable of minimizing the risk of adverse effects can be used to implement effective cancer therapy without impairing patient quality of life.

The ADC linker is a critical component that influences the overall drug efficacy and safety profiles(6,7). Cleavable linkers are used for nearly 70% of ADCs to efficiently liberate conjugated payloads inside the target cancer cells, leading to increased ADC potency(8). Among them, cathepsin-sensitive valine–citrulline (VCit) and similar dipeptide linkers connecting a payload via a p-aminobenzyloxycarbonyl (PABC) spacer are most commonly used as an industry-standard technology. Indeed, this linker system is used in more than 40 ADCs(9), such as Adcetris®(10), Polivy®(11), Padcev®(12), Zynlonta®(13), and Tivdak®(14) (Fig. 1A). However, patients treated with VCit-based ADCs and similar conjugates often suffer from dose-limiting toxicities. In Phase 2 and 3 studies of Adcetris®, an ADC equipped with monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) through VCit linkers, neutropenia (16–22% of patients)(15–17) or hepatotoxicity (7% of patients)(17) were common side effects leading to dose delays or treatment discontinuation. In a Phase 1 study of the anti-CD71 probody–VCit MMAE conjugate CX2029, Grade 3 or higher neutropenia was observed in 33% of patients(18). Suboptimal linker stability may partly contribute to such toxicities. We have demonstrated that glutamic acid–valine–citrulline (EVCit) tripeptide is an enzymatically cleavable linker with improved plasma stability(19) (Fig. 1B). The additional glutamic acid at the P3 position markedly reduces susceptibility to extracellular carboxylesterase 1c (Ces1c) found in rodent plasma(20), preventing premature payload release from the linker in mouse circulation. Although advantageous preclinically, as is the case with VCit linkers(21), the EVCit linker was shown to be susceptible to human neutrophil elastase-mediated degradation (described in detail in the Results section). Consequently, the population of neutrophils can be suppressed by prematurely released payloads, which may eventually cause neutropenia in patients.

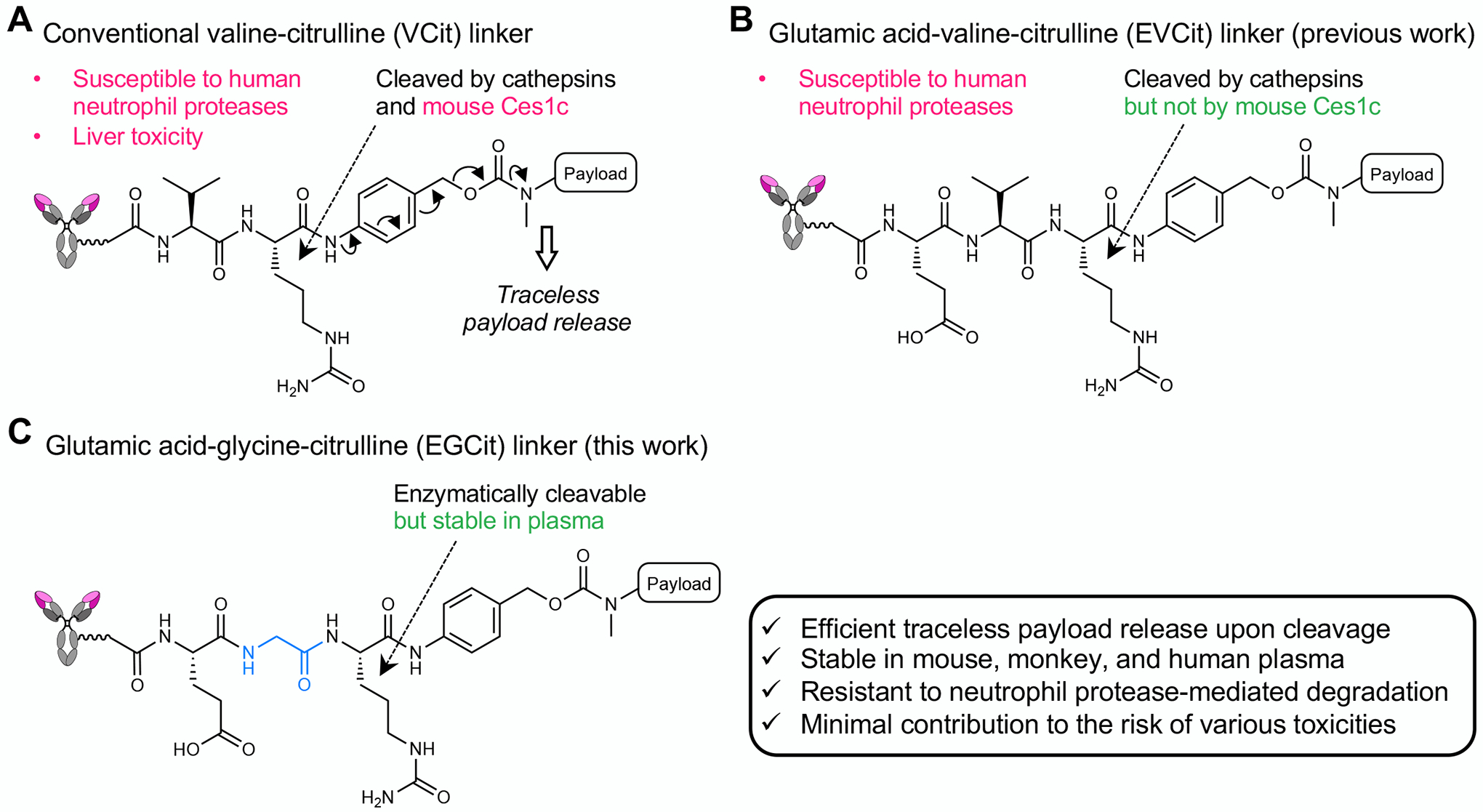

Fig. 1.

The structures and stability profiles of cleavable peptide linkers. A VCit-based ADC linker. VCit linkers are unstable in mouse circulation due to susceptibility to the extracellular carboxylesterase Ces1c. VCit linkers are also labile to human neutrophil elastase-mediated degradation. This instability often triggers premature payload release, leading to poor efficacy in preclinical rodent models and safety concerns including neutropenia and liver toxicity in humans. B EVCit-based ADC linker. We have previously developed EVCit linkers that are stable in human and mouse plasma. However, as shown in this study, this linker is also incapable of withstanding neutrophil elastase-mediated degradation. C EGCit-based ADC linker. This study demonstrates that EGCit linkers resist degradation in circulation and cleavage mediated by human neutrophil proteases while remaining capable of releasing payloads in a traceless manner upon intracellular cleavage.

Here we show that glutamic acid–glycine–citrulline (EGCit) tripeptide linkers have the potential to solve the abovementioned clinical issues without compromising ADC therapeutic efficacy (Fig. 1C). The EGCit sequence provides long-term stability in both mouse and primate plasma, spares differentiating human neutrophils, and retains the capacity to quickly liberate free payloads upon intracellular cleavage. This study also suggests that MMAE ADCs constructed with EGCit linkers can exhibit improved antitumor activity in a panel of cancer cell lines and in three different xenograft mouse models when compared to conventional conjugates, including FDA-approved anti-HER2 ADCs Kadcyla® (T-DM1) and Enhertu® (DS-8201). Notably, our EGCit-based ADC shows no significant myelosuppression or hepatotoxicity in healthy mice at 80 mg kg–1. Our findings indicate that the EGCit linker technology not only ensures smooth transition from preclinical research to clinical studies, but also provides a broadly applicable solution for substantially widening therapeutic windows of targeted drug delivery systems, including ADCs.

Materials and Methods

Supplementary appendix

A comprehensive and detailed description of all compounds, antibodies and conjugates, and methods used in this study is also provided in the Supplementary Data.

Cell culture

U87ΔEGFR-luc was generated by lentiviral transduction of U87ΔEGFR cells (a gift from Dr. Balveen Kaur, UTHealth) using Lentifect™ lentiviral particles encoding for firefly luciferase and a puromycin-resistant gene (GeneCopoeia, LP461–025). Transduction was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction. This cell line is vaiable from the authors for academic use upon reasonable request. JIMT-1 (AddexBio, RRID:CVCL_2077), SK-BR-3 (ATCC, RRID:CVCL_0033), and BT-474 (ATCC, RRID:CVCL_0179) were cultured in RPMI1640 (Corning) supplemented with 10% EquaFETAL® (Atlas Biologicals), GlutaMAX® (2 mM, Gibco), sodium pyruvate (1 mM, Corning), and penicillin-streptomycin (penicillin: 100 units mL–1; streptomycin: 100 μg mL–1, Gibco). KPL-4 (provided by Dr. Junichi Kurebayashi at Kawasaki Medical School, RRID:CVCL_5310), MDA-MB-453 (ATCC, RRID:CVCL_0418), MDA-MB-231 (ATCC, RRID:CVCL_0062), and U87ΔEGFR-luc were cultured in DMEM (Corning) supplemented with 10% EquaFETAL®, GlutaMAX® (2 mM), and penicillin-streptomycin (penicillin: 100 units mL–1; streptomycin: 100 μg mL–1). All cells were cultured at 37 °C under 5% CO2 and routinely tested using a Mycoalert Mycoplasma Contamination Kit (Lonza) to make sure there was no contamination in cell cultures. Cells were passaged before becoming fully confluent up to 20 passages. All cell lines were obtained from vendors or collaborators as described above within the period of 2014 to 2018, characterized by DNA profiling, and no further authentication was conducted by the authors. All cell lines were validated for antigen expression in cell-based ELISA prior to use.

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded in a culture-treated 96-well clear plate (5,000 cells per well in 50 μL culture medium) and incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 24 h. Serially diluted samples (50 μL) were added to each well and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 72 h for KPL-4, SK-BR-3, MDA-MB-231, and U87ΔEGFR-luc cells, and 96 h for JIMT-1, BT-474, and MDA-MB-453 cells. For DuoDM-ADCs, all the tested cell lines were incubated for 120 h. After the old medium was replaced with 100 μL fresh medium, 20 μL of a mixture of WST-8 (1.5 mg mL–1, Cayman chemical) and 1-methoxy-5-methylphenazinium methylsulfate (1-methoxy PMS, 100 μM, Cayman Chemical) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After gently agitating the plate, the absorbance at 460 nm was recorded using a BioTek Synergy HTX plate reader. EC50 values were calculated using Graph Pad Prism 9 software. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Human neutrophil viability assay

CD34-positive HSPCs isolated from the bone marrow were differentiated into neutrophils following the protocol reported by Zhao et al.(21) with modifications (see Supplementary Data for details). On Day 7 post differentiation, cell culture medium was replaced with fresh StemSpan™ SFEM II supplemented with G-CSF (30 ng mL–1), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and vehicle control or each ADC (200 nM) and cell density was adjusted to 1 × 105 cells mL–1. After being incubated for 7 days (Day 14), cells were measured for CD15 and CD66b by flow cytometry (see Supplementary Data for details). Effect of each ADC on the population of neutrophils was represented by percentage of CD66b/CD15-double positive cells in the viable cell population relative to that of the untreated group. Effect on the viability of all hematopoietic cells was represented by percentage of singlet cells relative to that of the untreated group.

Animal studies

All procedures were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines for animal care and use. All animals were housed under controlled conditions, namely 21–22 °C (± 0.5 °C), 30–75% (±10%) relative humidity, and 12:12 light/dark cycle with lights on at 7.00 am. Food and water were available ad libitum for all animals.

Tolerability study

Female old CD-1® IGS mice (6−8 weeks old, Charles River Laboratories, Strain Code: 022) received a single dose of each ADC (80 mg kg–1) intraperitoneally (Vehicle, n = 8; Kadcyla®, n = 7; Enhertu®, n = 7; EGCit ADC 4c, n = 8; MC-VCit MMAE DAR 4 ADC, n = 6). Body weight was monitored every day for 5 days (Note: 4 mice in the vehicle group were used for the following blood chemistry analysis without body weight monitoring, thus these mice were not included in this tolerability assessment). Humane endpoints were defined as 1) greater than 20% weight loss or 2) severe signs of distress. However, no mice met these criteria over the course of study. Five days post injection, these mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and the whole blood was drawn by heart puncture for following blood chemistry and hematology analysis. For following histology analysis, livers were also harvested, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in cold PBS at 4 °C for 2 days, immersed in cold PBS at 4 °C for 24 h, and stored in 70% ethanol until use.

Blood chemistry, histology, and hematology analysis

[1] Blood chemistry. Whole blood (400–600 μL) was drawn from a part of the mice used or prepared in the tolerability study described above (vehicle, n = 4; all other groups, n = 3) using S-Monovette® charged with serum gel (1.1 mL syringe, Sarstedt) and allowed to clot at room temperature for 30–40 min. After centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 min, resulting serum samples (150 μL) were loaded onto NSAID 6 clips specialized for identifying liver damage (IDEXX, Westbrook, ME) and analyzed using a Catalyst Dx Chemistry Analyzer (IDEXX). [2] Histology. Paraffin-embedded liver sections were prepared using the fixed livers and then stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Subsequently, bright-field images of the H&E-stained tissues (×20) were taken using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope. Images were processed using NIS-Element software (version 4.51.00) and analyzed using Image J. [3] Hematology. whole blood (700–1,000 μL) was drawn from a part of the mice used in the tolerability study described above (n = 4 for all groups) using S-Monovette® charged with K3 EDTA (1.1 mL syringe, Sarstedt). Blood samples were gently mixed well by inversion and stored on ice until analysis (for less than 4 h). Each blood sample (500 μL) was analyzed using a Procyte Dx® (IDEXX).

In vivo xenograft mouse models of human breast cancer

[1] KPL-4 model. Cells (1 × 107 cells) suspended in 100 μL of 1:1 PBS/Cultrex® BME Type 3 (Trevigen) were orthotopically injected into the inguinal mammary fat pad of female NSG mice (6−8 weeks old, purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, Stock number: 005557, maintained by in-house breeding). When the tumor volume reached ~100 mm3, mice were randomly assigned to six groups (n = 5 for each group) and a single dose of each ADC (1 mg kg–1) or vehicle was administered to mice intravenously. Tumor volume (0.52 × a × b2, a: long diameter, b: short diameter) and body weight were monitored twice a week using a digital caliper. Mice were euthanized when the tumor volume exceeded 1,000 mm3, the tumor size exceeded 2 cm in diameter, greater than 20% weight loss was observed, or mice showed signs of distress. Such events were counted as deaths. [2] JIMT-1/MDA-MB-231 admixed tumor model. A co-suspension of 1 × 107 JIMT-1 cells and 2.5 × 106 MDA-MB-231 cells in 100 μL of 1:1 PBS/Cultrex® BME Type 3 (Trevigen) was orthotopically injected into the inguinal mammary fat pad of female NU/J mice (6−8 weeks old, The Jackson Laboratory, Stock number: 002019). On day 7 post transplantation, mice were randomly assigned to each group (n = 5 for Enhertu®; n = 6 for EGCit-MMAE/F dual-drug ADC 7a) and injected intravenously with sterile-filtered human IgG (30 mg kg–1, Innovative Research, catalog number: IRHUGGFLY1G) in PBS. The next day, a single dose of Enhertu® (3 mg kg–1) or dual-drug ADC 7a (1 mg kg–1) was administered to mice intravenously. Tumor volume (0.52 × a × b2, a: long diameter, b: short diameter) and body weight were monitored twice a week. Mice were euthanized when the tumor volume exceeded 1,000 mm3, the tumor size exceeded 2 cm in diameter, or mice showed severe signs of distress. Such events were counted as deaths.

Orthotopic xenograft mouse model of human GBM

U87ΔEGFR-luc cells (1 × 105 cells) were stereotactically implanted into NSG mice (6–8 weeks old, male) as follows. NSG mice were injected intraperitoneally with a cocktail of ketamine (67.5 mg kg–1) and dexmedetomidine (0.45 mg kg–1) and maintained at 37 °C on a heating pad until the completion of surgery. After the head skin was shaved and treated with 10 μL of 0.25% bupivacaine supplemented with epinephrine (1:200,000), anesthetized mice were placed on a stereotactic instrument. After disinfecting the head skin with chlorhexidine and ethanol, a small incision was made and then a burr hose was drilled into the skull over the right hemisphere (1 mm anterior and 2 mm lateral to the bregma). A 10 μL Hamilton syringe (model 701 N) was loaded with cells suspended in 2 μL cold hanks-balanced salt solution (HBSS) and slowly inserted into the right hemisphere through the burr hole (3.5 mm depth). After a 1-min hold time, cells were injected over a 5-min period (0.4 μL min–1). After a 3-min hold time, the needle was retracted at a rate of 0.75 mm min–1. The incision was closed using GLUture® (Zoetis) and mice were injected with atipamezole (1 mg kg–1, i.p.). At day 5 post implantation, brain tumor-bearing NSG mice were randomized and injected intravenously with a single dose of either ADC (5 mg kg–1, n = 6 for VCit ADC 8a; n = 7 for EGCit ADC 8b) or PBS (n = 6). Body weight was monitored every 3–4 days and mice were euthanized when body weight loss of >20% or any severe clinical symptom was observed. Such events were counted as deaths.

Statistical analysis

Although no statistical analysis was performed prior to performing experiments, sample size was determined by following methods for similar experiments in the field reported previously. We did not use the vehicle control in the xenograft breast cancer studies for statistical analysis. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments. For the quantification of intracellularly released MMAE and human neutrophil viability assay, a one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. For blood chemistry and hematology analysis and xenograft tumor model studies, a Welch’s t-test (two-tailed, unpaired, uneven variance) was used. Kaplan-Meier survival curve statistics were analyzed with a logrank (Mantel–Cox) test. To control the family-wise error rate in multiple comparisons, crude P values were adjusted by the Holm–Bonferroni method. Differences with adjusted P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analysis. See Table S9 for all P values.

Data Availability

All data supporting the findings in this study are available within the paper, its supplementary Data file, or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Incorporating glycine at the P2 position and glutamic acid at the P3 position increases resistance to undesired degradation leading to premature payload release.

To seek alternatives to the conventional VCit linker with improved in vivo stability and tolerability, we first investigated how the linker instability leading to neutropenia could be circumvented. Serine proteases secreted extracellularly from differentiating human neutrophils have been shown to promote the release of MMAE from VCit-based ADCs, reducing the population of bone marrow neutrophils(21). With this in mind, we set out to identify the cleavage site by neutrophil elastase using small-molecule probes (see Supplementary Notes for synthesis details). VCit–PABC–pyrene probe 1 was incubated with human neutrophil elastase at 37 °C for 24 h. A pyrene fragment containing citrulline–PABC was found to be the major product by liquid chromatography (LC)–electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) (Fig. 2A). This result indicates that neutrophil elastase cleaves the amide bond between P1 citrulline and P2 valine. Although no supporting data were presented, Miller et al. recently reported the same observation(22). EVCit probe 2 also yielded the same citrulline-containing fragment, suggesting that glutamic acid at P3 does not protect the linker from neutrophil elastase-mediated degradation.

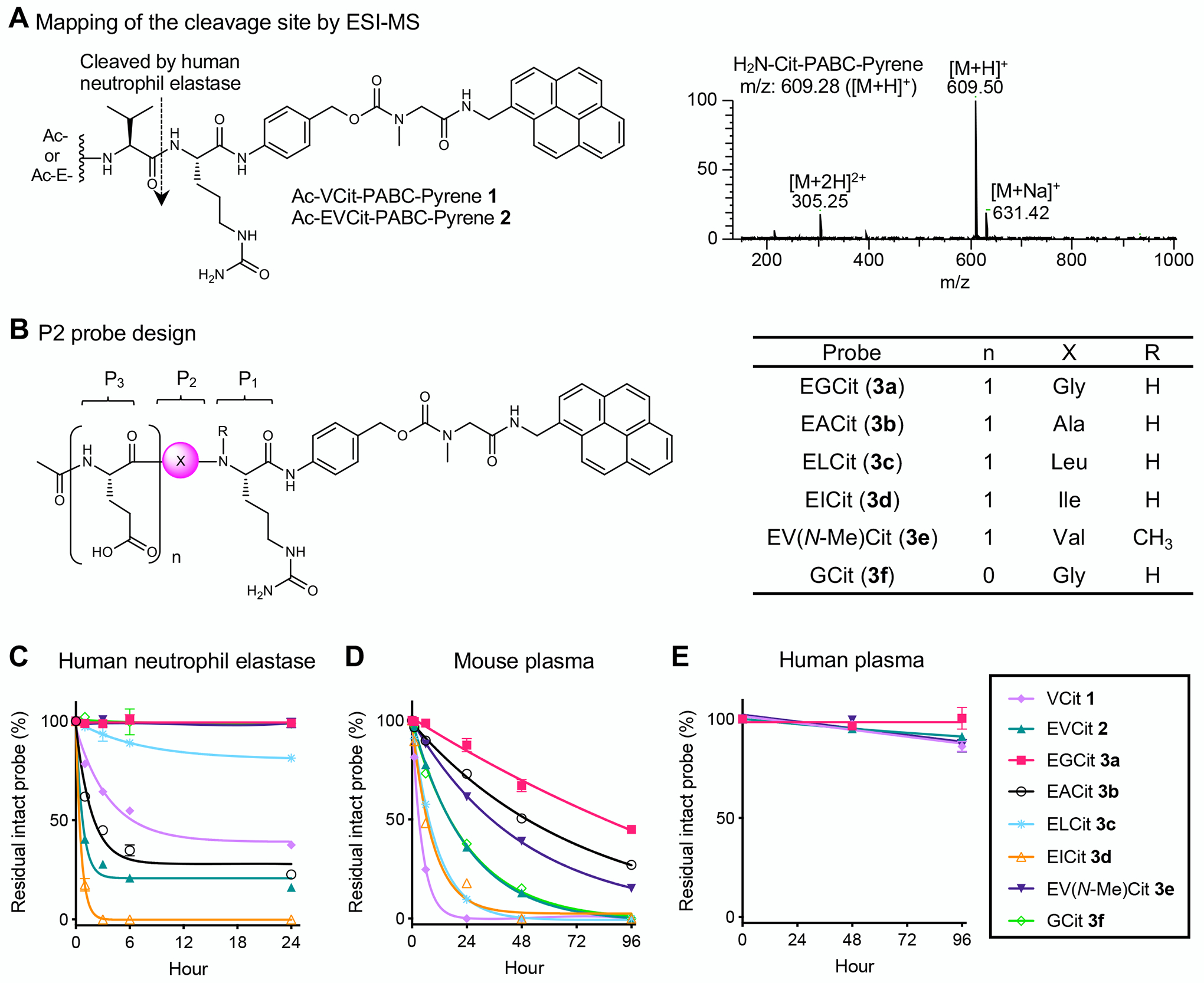

Fig. 2.

Incorporating glycine at the P2 position and glutamic acid at the P3 position increases resistance to undesired degradation leading to premature payload release. A ESI-MS-based mapping of the cleavage site in the presence of human neutrophil elastase. We observed cleavage of the amide bond between valine and citrulline within VCit (1) and EVCit (2) probes. B Structures of small-molecule P2 probes containing EGCit (3a), EACit (3b), ELCit (3c), EICit (3d), EV(N-Me)Cit (3e), or GCit (3f). A pyrene group was used as a surrogate of hydrophobic ADC payloads. C–E Stability of probes 1, 2, and 3a–f in the presence of human neutrophil elastase (C), in undiluted BALB/c mouse plasma (D), and in undiluted human plasma (E) at 37 °C. (1) light purple diamond; (2) green triangle; (3a) magenta square; (3b) black open circle; (3c) cyan asterisk; (3d) orange open triangle; (3e) purple inversed triangle; (3f) light green open diamond. All assays were performed at least three times in technical duplicate, and representative data from the replicates are shown (n = 2). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. PABC, p-aminobenzyloxycarbonyl.

Based on this initial analysis, we screened various amino acids at the P2 position. We prepared a panel of pyrene probes containing an EXCit–PABC unit where X is glycine (3a), alanine (3b), leucine (3c), and isoleucine (3d) (Fig. 2B). We also prepared EV(N-Me)Cit probe 3e and GCit dipeptide probe 3f (see Supplementary Notes for synthesis details). Subsequently, all probes were tested for stability against human neutrophil elastase-mediated degradation (Fig. 2C). Surprisingly, EVCit probe 2 degraded more quickly than VCit probe 1, indicating that the P3 glutamic acid can increase the linker susceptibility to elastase-mediated degradation. EACit and EICit probes 3b,d also rapidly degraded. These results are consistent with a previous study demonstrating that human neutrophil elastase preferentially cleaves the N-terminus amide bonds of valine, alanine, and isoleucine(23). In contrast, we observed marginal or almost no degradation for probes containing EGCit (3a), ELCit (3c), EV(N-Me)Cit (3e), or GCit (3f). This observation suggests that the P2 amino acid impacts the reactivity with neutrophil elastase more significantly than the P3 amino acid. We further tested EGCit and EV(N-Me)Cit probes 3a,e for resistance to cleavage by other abundant proteases secreted by human neutrophils: human proteinase 3 and cathepsin G. EGCit probe 3a was completely intact in the presence of either protease while EV(N-Me)Cit probe 3e was partially degraded by proteinase 3 (Table S1).

Next, we tested probes 3a–f for stability in undiluted BALB/c mouse plasma (Fig. 2D). EGCit, EACit, and EV(N-Me)Cit probes 3a,b,e showed improved stability compared to EVCit probe 2. In particular, about 45% of EGCit probe 3a remained intact after a 4-day incubation. GCit probe 3f was less stable than EGCit probe 3a, which is consistent with our previous finding that glutamic acid at the P3 position enhances linker stability in mouse plasma. Furthermore, EGCit probe 3a completely withstood degradation in monkey and human plasma (Fig. 2E and Table S2). Finally, we performed another set of stability assays for EFCit, E(N-Me)VCit, (N-Me)VCit, and V(N-Me)Cit probes. However, these probes exhibited promoted degradation in mouse plasma or cleavage mediated by neutrophil elastase (Fig. S1). Collectively, these findings suggest that the EGCit sequence offers greatly enhanced stability against undesired proteolytic degradation leading to premature payload release.

EGCit linker increases ADC hydrophilicity and cell killing potency with efficient intracellular payload release.

We set out to investigate how the P2 amino acids evaluated above affect ADC physicochemical properties, intracellular payload release upon cleavage, and antigen-specific cell killing potency. To this end, we constructed anti-HER2 ADCs using selected P2-modified cleavable linkers and the conjugation technology developed by us (Fig. 3A)(19,24,25). First, diazide branched linkers were site-specifically installed onto the side chain of glutamine 295 (Q295) within N297A anti-HER2 mAb (derived from trastuzumab) by microbial transglutaminase (MTGase)-mediated transpeptidation. In parallel, we prepared EVCit, EGCit, EV(N-Me)Cit, and GCit linker-based modules containing bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne (BCN) as a handle for strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition, polyethylene glycol (PEG), PABC as a self-immolative spacer, and MMAE as a payload (see Supplementary Notes for synthesis details). Finally, these payload modules underwent the click reaction with the mAb–tetraazide to afford homogeneous anti-HER2 ADCs 4a–e with a drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) of 4. The homogeneity of each conjugate was confirmed by ESI-MS analysis (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Notes). We confirmed by SEC analysis that no significant dissociation or aggregation occurred after incubating each ADC in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 28 days (Fig. S2). Subsequently, we performed hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) analysis under physiological conditions (phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) to assess the relative hydrophobicity of each ADC (Fig. 2C). EGCit ADC 4c was the least hydrophobic of the ADCs tested. EVCit ADC 4b, EV(N-Me)Cit ADC 4d, and GCit ADC 4e had intermediate hydrophobicity. VCit ADC 4a was the most hydrophobic conjugate. This result suggests that incorporating the smallest amino acid glycine at the P2 position and negatively charged glutamic acid at the P3 position can synergistically reduce ADC hydrophobicity at physiological pH. This feature is advantageous in the construction of ADCs because hydrophobic ADCs often show high aggregation rates leading to fast clearance(26).

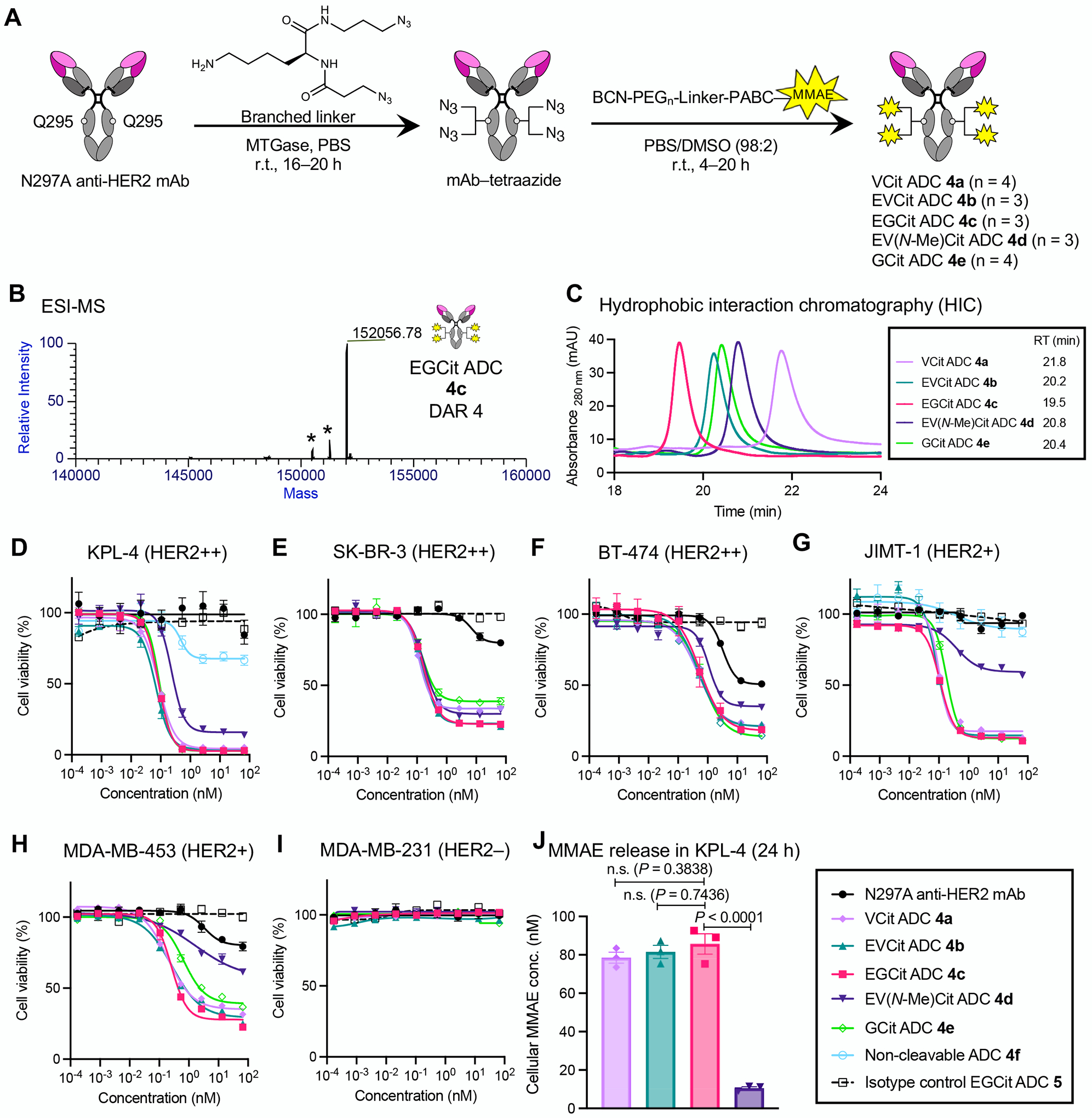

Fig. 3.

EGCit linker increases ADC hydrophilicity and cell killing potency with efficient intracellular payload release. A Construction of ADCs (4a–e) by MTGase-mediated branched linker conjugation and following strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition (yellow spark: MMAE). B Deconvoluted ESI-MS trace of EGCit ADC 4c. Asterisk (*) indicates a fragment ion detected in ESI-MS analysis. See Supplementary Notes for mass traces of the other ADCs. C Overlay of five HIC traces (VCit ADC 4a: light purple; EVCit ADC 4b: green; EGCit ADC 4c: magenta; EV(N-Me)Cit ADC 4d: purple; GCit ADC 4e: light green) under physiological conditions (phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). D–I Cell killing potency in the breast cancer cell lines KPL-4 (D), SK-BR-3 (E), BT-474 (F), JIMT-1 (G), MDA-MB-453 (H), and MDA-MB-231 (I). We tested unconjugated N297A anti-HER2 mAb (black circle), VCit ADC 4a (light purple diamond), EVCit ADC 4b (green triangle), EGCit ADC 4c (magenta square), EV(N-Me)Cit 4d (purple inversed triangle), GCit ADC 4e (light green open diamond), non-cleavable ADC 4f (cyan open circle), and isotype control EGCit ADC 5 (black open rectangle with dotted curve). J ESI-MS-based quantification of free MMAE released from ADCs 4a–c in KPL-4 cells after incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. All assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. For statistical analysis, a one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s post hoc test was used (comparison control: EGCit ADC 4c). BCN, bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne; DAR, drug-to-antibody ratio; MMAE, monomethyl auristatin E; MTGase, microbial transglutaminase; PEG, polyethylene glycol; RT, retention time.

Next, we tested the ADCs for HER2-binding affinity using cell-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). We used the human breast cancer cell lines KPL-4 (HER2-positive) and MDA-MB-231(HER2-negative) (Fig. S2 and Table S3). We confirmed that all anti-HER2 ADCs retained high binding affinity for KPL-4 (KD: 0.084–0.156 nM) but not for MDA-MB-231. We then evaluated these ADCs for in vitro cytotoxicity in HER2-positive (KPL-4, SK-BR-3, BT-474, JIMT-1, MDA-MB-453) and HER2-negative (MDA-MB-231) human breast cancer cell lines (Fig. 3D–I). As controls, we also prepared and tested non-cleavable anti-HER2 MMAE ADC 4f (DAR 4) and an isotype control ADC constructed using the BCN–EGCit–PABC–MMAE module (5, DAR 4). VCit ADC 4a, EVCit ADC 4b, and EGCit ADC 4c exhibited comparable cell killing potency in the HER2-positive cell lines, but not in HER2-negative MDA-MB-231 cells; under our assay conditions, the EC50 values of these ADCs were 0.070–0.084 nM in KPL-4, 0.120–0.167 nM in SK-BR-3, 0.470–0.543 nM in BT-474, 0.086–0.110 nM in JIMT-1, and 0.193–0.272 nM in MDA-MB-453 (Table S4). These ADCs also showed similar maximum cell killing potency at high concentrations (Table S5). EV(N-Me)Cit ADC 4d exhibited a similar EC50 value in SK-BR-3. However, its EC50 values and cell viability at high concentrations were greater than those of EGCit ADC 4c in the other HER2-positive cell lines. GCit ADC 4e was as potent as EGCit 4c in KPL-4, JIMT-1, and BT-474; however, GCit ADC 4e was less effective in SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-453 than EGCit 4c as indicated by the increased EC50 value and percentage of viable cells at the maximum ADC concentration. Non-cleavable anti-HER2 ADC 4f, which lacked a peptide cleavable sequence within the linker scaffold, showed far greater EC50 values in KPL-4 and JIMT-1 cells compared to cleavable ADCs 4a–c. Furthermore, isotype control EGCit ADC 5 showed almost no cell killing effect in either cell line. These findings highlight the importance of internalization and the following intracellular release of free MMAE for effective cell killing. The comparable binding affinities and potencies also suggest that ADCs 4a–c can deliver a similar amount of MMAE to the targeted cells. To verify this point, we quantified free MMAE released from ADC 4a–d in KPL-4 cells (Fig. 3J). After treating KPL-4 cells with each ADC for 24 h, the MMAE concentrations in cell lysates were determined by high-resolution ESI-MS. As anticipated, about 80% of conjugated MMAE was detected as a free payload in the VCit, EVCit, and EGCit ADCs 4a–c. In contrast, we observed only 10% MMAE release for EV(N-Me)Cit ADC 4d, indicating that the N-methylation of the citrulline retarded the payload release. Detailed analysis of other parameters (e.g., internalization rate) in addition to linker cleavage will provide how each parameter influences the overall payload release kinetics and intracellular accumulation. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the hydrophilic EGCit sequence enables efficient traceless payload release upon ADC internalization in a wide range of cell types with varying catabolic profiles, ensuring maximal ADC potency.

EGCit ADC is stable in plasma and spares differentiating human neutrophils.

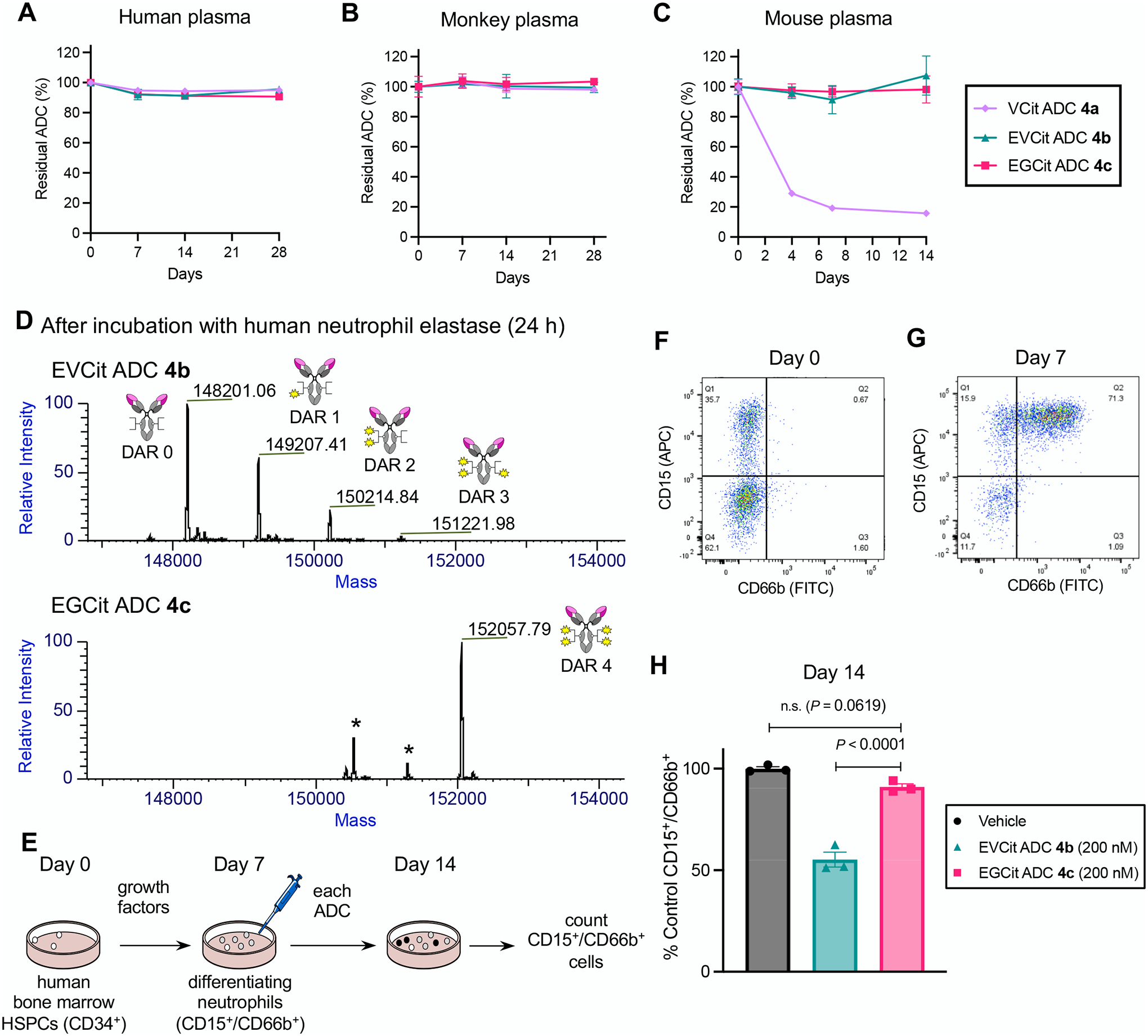

To assess ADC stability and safety profiles, we first tested ADCs 4a–c for plasma stability. We observed no significant degradation in either ADC after a 28-day incubation in undiluted human and monkey plasma at 37 °C (Fig. 4A,B and Table S6,S7). EVCit and EGCit ADCs 4b,c showed almost no linker cleavage after a 14-day incubation in undiluted BALB/c mouse plasma (Fig. 4C and Table S8). In contrast, VCit ADC 4a lost approximately 74% of the conjugated MMAE after the same period of time. Next, we evaluated the stability of these ADCs in the presence of human neutrophil elastase (Fig. 4D). EVCit ADCs 4b underwent partial degradation and DAR 0–3 fragments were generated. However, EGCit ADC 4c completely resisted degradation. These results are consistent with the earlier studies using pyrene probes (Fig. 2C–E).

Fig. 4.

EGCit ADC is stable in plasma and spares differentiating human neutrophils derived from the bone marrow. A–C Stability at 37 °C in undiluted human plasma (A), cynomolgus monkey plasma (B), and BALB/c mouse plasma (C). VCit ADC 4a (light purple diamond), EVCit ADC 4b (green triangle), and EGCit ADC 4c (magenta square) were tested. D ESI-MS traces of ADCs 4b,c after incubation with human neutrophil elastase at 37 °C for 24 h. EGCit ADC 4c did not undergo cleavage, whereas EVCit ADC 4b underwent linker degradation and lost part of its payloads. E Study schedule for differentiation of human bone marrow HSPCs into neutrophils and subsequent treatment with ADCs 4b,c. After 3-day expansion (Day 0), HSPCs were treated with growth factors for 7 days and differentiated into CD15+ and CD66b+ granulocytes/neutrophils. F,G Flow cytometry before (Day 0, F) and after (Day 7, G) differentiation. H The effects of ADCs (vehicle, dark gray; EVCit ADC 4b, green; EGCit ADC 4c, magenta) on the population of human neutrophils relative to those of vehicle control (n = 3). All assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. For statistical analysis, a one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s post hoc test was used (comparison control: EGCit ADC 4c). HSPCs, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

To investigate the potential effect of our ADCs on neutrophil production in human bone marrow, we performed ex vivo differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) into neutrophils followed by ADC treatment (Fig. 4E). Zhao et al. reported that the population of differentiating human neutrophils was markedly decreased by ADCs equipped with MMAE via a VCit linker, but mature neutrophils could tolerate the toxic effect(21). Following their protocol with some modifications, we differentiated HSPCs collected from a single donor into granulocytes with growth factors over a period of 7 days. At this point, the population of viable cells expressing both granulocyte markers CD15 and CD66b increased from 0.7% to 71.3% (Fig. 4F,G and Fig. S3). Because neutrophils are the most abundant granulocyte type in humans (50–75% of all leukocytes), we considered these CD15/CD66b double-positive cells to be a population representing differentiating neutrophils. Then, these cells were treated with 200 nM of EVCit and EGCit ADCs 4b,c. For EGCit ADC 4c, we did not observe a significant decrease in the percentage of CD15+/CD66b+ cells relative to that in the vehicle group (Fig. 4H and Fig. S3). In contrast, the relative neutrophil population significantly decreased to 55% by treatment with EVCit ADC 4b. Collectively, these results highlight the potential of the EGCit linker to reduce the risk of myelosuppression, in particular neutropenia caused by prematurely released ADC payloads.

EGCit linker has the potential to minimize the antigen-independent myelotoxicity and hepatotoxicity of ADCs.

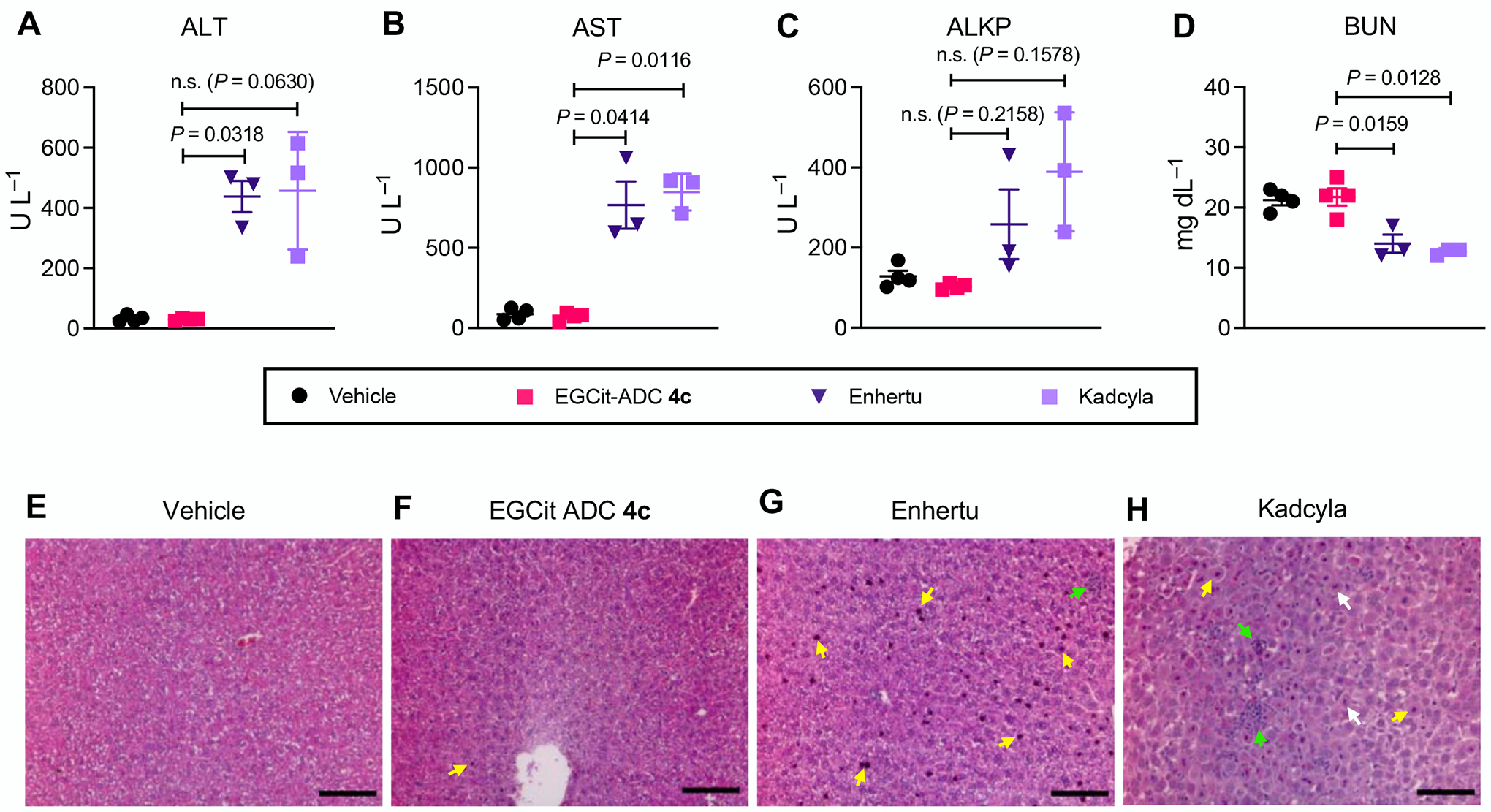

To investigate whether or not the cleavable EGCit linker alters ADC safety at therapeutic doses, we performed an exploratory toxicology study. Healthy CD-1® IGS mice were injected with EGCit MMAE ADC 4c, Enhertu®, or Kadcyla® at 80 mg kg–1 and monitored over the course of 5 days. A maleimide-linked VCit MMAE ADC was also tested as a conventional example. We did not observe any significant body weight loss or other severe clinical symptom in the treatment groups, except in the maleimide–VCit ADC group; all mice treated with this ADC lost about 15% of their body mass, and one mouse died on Day 3 (Fig. S4). Next, to evaluate the potential liver toxicity of our ADC and the two approved ADCs, a blood chemistry test was performed by collecting serum at the end of the 5-day monitoring (Fig. 5A–D). We quantified the following molecules associated with liver functions: alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALKP), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Increased ALT, AST, and ALKP as well as decreased BUN generally indicate liver damage. In the case of our EGCit ADC, the values of these parameters were comparable to those of the untreated cohort. In contrast, mice treated with Enhertu® and Kadcyla® showed elevated ALT, elevated AST, and decreased BUN. The ALKP level also appeared to increase with these two ADCs. We validated this observation by performing histological analysis using livers collected from the mice (Fig. 5E–H). We observed a marginal amount of nucleus condensation for most of the tissue samples collected from the EGCit ADC group (Fig. 5F). Compared to this group, condensed nuclei and inflamed regions were more evident in tissue samples treated with Enhertu® and Kadcyla® (Fig. 5G,H). In addition, we observed hepatocellular ballooning and nucleus fragmentation in the Kadcyla® group (Fig. 5H). These findings indicate that both EGCit ADC 4c and Enhertu® caused low to moderate hepatocyte apoptosis and that Kadcyla® caused severe liver damage. Hematological analysis was also performed by collecting whole blood on Day 5. We observed no significant change in red blood cell, platelet, and neutrophil counts for our ADC or Enhertu® compared to the untreated cohort. In contrast, three out of four mice treated with Kadcyla® showed markedly decreased platelet counts and increased neutrophil counts (Fig. S4), which is consistent with previous observations(27–29). Although more detailed pathological analysis needs to be performed, we observed significant decreases in platelet (two out of three mice) and neutrophil counts (one out of three mice) for VCit ADC S21. This observation demonstrates that the VCit ADC was much less tolerated than the other ADCs tested probably because of its instability in mouse circulation, precluding precise assessment of toxicity profiles. Overall, these results suggest that the safety of our EGCit MMAE ADC is greater than that of its clinical competitors.

Fig. 5.

The EGCit linker has the potential to minimize antigen-independent hepatotoxicity of ADCs. A–D Blood chemistry parameters (ALT (A), AST (B), ALKP (C), and BUN (D)) measured 5 days post ADC injection to 6–8 weeks female CD-1® mice. Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose of vehicle control (n = 4), EGCit ADC 4c (magenta square, n = 4), Enhertu® (purple inversed triangle, n = 3), or Kadcyla® (light purple square, n = 3) at 80 mg kg−1. Data are presented as mean values (bars) ± SEM. For statistical analysis, a Welch’s t-test (two-tailed, unpaired, uneven variance) was used. To control the family-wise error rate in multiple comparisons, crude P values were adjusted by the Holm–Bonferroni method. E–H H&E-stained liver sections 5 days post treatment with vehicle (E), EGCit ADC 4c (F), Enhertu® (G), or Kadcyla® (H). Morphological changes are indicated with color arrows (yellow: condensed nuclei; green: necrosis and inflammation; white: fragmented nuclei). Scale bar: 100 μm. This experiment was repeated more than twice independently with similar results. ALKP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen, H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

EGCit ADCs exert improved antitumor effects in various xenograft models compared to conventional ADCs.

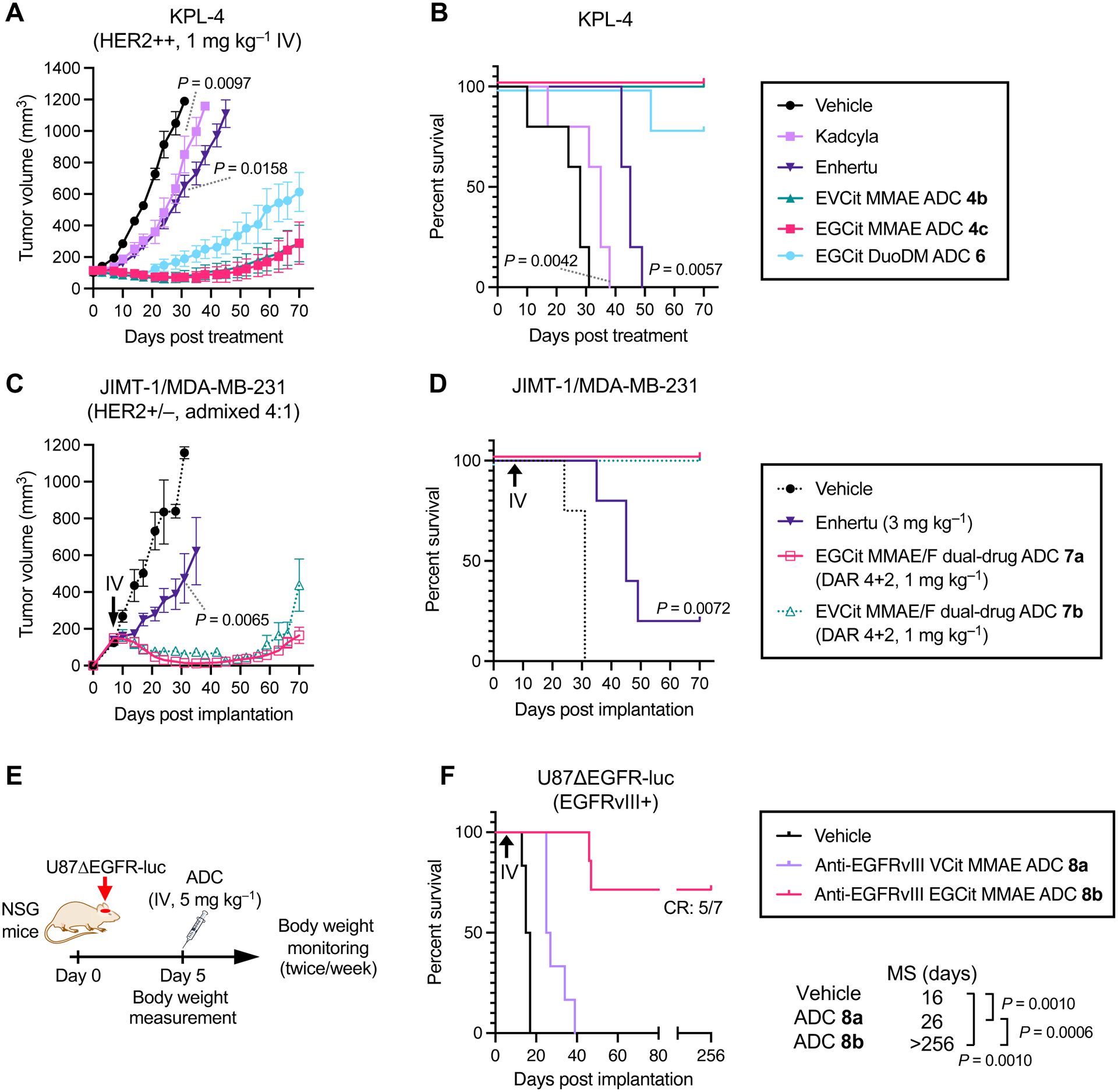

We sought to evaluate EGCit-based ADCs for treatment efficacy in multiple xenograft mouse tumor models (Fig. 6A–F). In the KPL-4 inflammatory breast tumor model, orthotopically xenografted NOD-scid gamma (NSG) mice were injected intravenously with a single dose of our anti-HER2 ADCs 4b,c, Kadcyla®, or Enhertu® at 1 mg kg–1. To examine the applicability of our EGCit linker technology, we also prepared and tested duocarmycin DM (DuoDM) ADCs 6 (See Supplementary Notes). This ADC showed sub-nanomolar EC50 values in vitro (0.114 nM in KPL-4 and 0.060 nM in JIMT-1) as seen for MMAE ADC 4c, demonstrating that the EGCit linker can also release DuoDM efficiently (Fig. S5 and Table S3). We did not observe any significant acute toxicity associated with administration of ADCs 4b,c and 6 over the course of study as evaluated by monitoring significant body weight loss and other clinical symptoms (Fig. S6). In addition, these ADCs exhibited remarkable percent tumor growth inhibition (%TGI on Day 31: 107%, ADC 4b; 104%, ADC 4c; 94%, ADC 6) and survival benefits (animal death by Day 70: no death, 4b,c; 1 out of 5 mice, ADC 6) (Fig. 6A,B and Fig. S6). In contrast, compared to EGCit ADC 4c, only limited tumor growth inhibition was observed for Kadcyla® (47%TGI, P = 0.0097) and Enhertu® (48%TGI, P = 0.0158). All animals treated with these FDA-approved ADCs were found dead or killed at the pre-defined humane endpoint (>1,000 mm3 tumor size or >20% body weight loss) by the end of the study (median survival time: 35 days, Kadcyla®, 45 days, Enhertu®).

Fig. 6.

EGCit ADCs exert improved antitumor effects in various xenograft models compared to conventional ADCs. A–D Anti-tumor activity (A, C) and survival benefit (B, D) in orthotopic xenograft mouse models of human breast cancer. KPL-4 model (A, B): a single dose of vehicle control (black circle), Kadcyla® (light purple square), Enhertu® (purple inversed triangle), EVCit-MMAE ADC 4b (green triangle), EGCit-MMAE ADC 4c (magenta square) or EGCit-DuoDM ADC 6 (cyan circle) was intravenously administered at 1 mg kg–1 to tumor-bearing female NSG mice at a mean tumor volume of ~100 mm3 (n = 5 for all groups). JIMT-1/MDA-MB-231 4:1 admixed model (C, D): eight days post implantation (indicated with a black arrow), female NU/J mice were intravenously administered with a single dose of Enhertu® (3 mg kg –1, purple inversed triangle, n = 5) or EGCit-MMAE/F DAR 4+2 dual-drug ADC 7a, (1 mg kg–1, magenta open square, n = 6). Note: The tumor volume and survival curve data of vehicle control (black circle with dotted curve, n = 4) and EVCit dual-drug ADC 7b (1 mg kg–1, green open triangle with dotted curve, n = 5) presented here were previously reported by us(30). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. E,F study schedule in the U87ΔEGFR-luc orthotopic xenograft model (E) and survival curves after treatment (F). U87ΔEGFR-luc cells were intracranially implanted to male NSG mice. Five days post implantation, mice were intravenously administered with a single dose of vehicle control (black, n = 6), anti-EGFRvIII VCit-MMAE ADC 8a (5 mg kg–1, light purple, n = 6), or anti-EGFRvIII EGCit-MMAE ADC 8b (5 mg kg–1, magenta, n = 7). All animals other than the ones that were found dead or achieved complete remission were killed at the pre-defined humane endpoint, which were counted as deaths. For statistical analysis of the tumor volume data, a Welch’s t-test (two-tailed, unpaired, uneven variance) was used. Kaplan-Meier survival curve statistics were analyzed with a logrank (Mantel–Cox) test. To control the family-wise error rate in multiple comparisons, crude P values were adjusted by the Holm–Bonferroni method. CR, complete remission; DuoDM, duocarmycin DM.

Next, we tested the clinical potential of the EGCit linker in the dual-drug ADC format. We have demonstrated that a dual-drug ADC equipped with MMAE and MMAF can effectively treat low-HER2 heterogeneous breast tumors with elevated drug resistance(30). We prepared EGCit-based MMAE/F DAR 4+2 ADC 7a (see Supplementary Data for details). This ADC and Enhertu® were tested in the JIMT-1/MDA-MB-231 admixed tumor model established by us previously: a model of refractory human breast cancer characterized by aggressive growth, heterogeneous low-HER2 expression, and moderate resistance to hydrophobic payloads such as MMAE(30). A single dose of each ADC (Enhertu®, 3 mg kg–1; ADC 7a, 1 mg kg–1) was intravenously administered to orthotopic tumor-bearing nude mice 8 days post-implantation (average tumor volume: 100–150 mm3). No acute toxicity associated with ADC administration was observed for either ADC (Fig. S6). EGCit dual-drug ADC 7a exhibited remarkable antitumor effects (112%TGI on Day 31, Fig. 6C and Fig. S6) and survival benefits (no animal death by Day 70, Fig. 6D). This treatment outcome is comparable to our observation for EVCit variant 7b (107%TGI on Day 31) tested in our recent report(30), suggesting that the cleavable EGCit linker is as good at enhancing in vivo ADC efficacy and circulation stability as our previous EVCit linker. In contrast, even with an increased dose (3 mg kg–1), Enhertu® exhibited only moderate inhibition of tumor growth in this HER2 heterogeneous tumor model (76%TGI on Day 31, P = 0.0065, comparison control: EGCit ADC 7a). Furthermore, 4 out of 5 mice needed to be euthanized by the end of the study due to severe clinical symptoms, including tumor ulceration.

Although these studies indicate the superiority of our linker system, readers should be aware that the dosing schedule of each ADC was not adjusted based on the differences in pharmacokinetics. The payload-based half-lives of Kadcyla® and Enhertu® at the elimination phase are 3–5 days(31) and 8.23 days(32), respectively. Based on the high structural similarity to our previous EVCit ADCs(19,30), we expect the half-lives of EGCit ADCs are 12–16 days. As such, Kadcyla® and Enhertu® could have exhibited better efficacy in our studies with dose adjustment. Even so, the EGCit linker system is likely advantageous from a therapeutic window standpoint based on its improved safety profiles, as shown in Fig. 5.

Finally, we set out to establish the generalizability of our linker technology by testing in an orthotopic glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) model (Fig. 6E,F). ADC-based systemic treatment of GBM has been unsuccessful as demonstrated by the recent failure of depatuxizumab mafodotin (Depatux-M, formerly called ABT-414)(33) and AMG-595(34) in clinical trials. Using our linker technology, we could construct a panel of homogeneous anti-epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII) ADCs from N297A depatuxizumab, including conventional VCit ADC 8a, EGCit ADC 8b, and EGCit–DuoDM ADCs conjugated via PABC or p-aminobenzyl quaternary ammonium (PABQ)(35) linkage (see Supplementary Notes for preparation and characterization details). These ADCs were equally potent in EGFRvIII-positive U87ΔEGFR-luc GBM cells (Fig. S5). ADCs 8a,b were then tested in the orthotopic U87ΔEGFR-luc model (Fig. 6E). Intracranial tumor-bearing NSG mice were injected intravenously with a single dose of each ADC at 5 mg kg–1 5 days post-implantation. No acute toxicity associated with ADC administration was observed in either group (Fig. S6). The short survival time of the untreated cohort (median survival time: 16 days) demonstrates the aggressive tumor growth of this model (Fig. 6F). EGCit ADC 8b exerted remarkable therapeutic efficacy; the median survival time was extended to >256 days, and 5 out of 7 mice achieved complete remission without any symptoms or tumor lesions at the end of the study [confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 256 days post tumor implantation, Fig. S6]. In contrast, conventional VCit ADC 8a moderately extended the median survival time to 26 days (P = 0.001, vs vehicle; P = 0.0006, vs EGCit ADC 8b). All mice treated with VCit ADC 8a died or were euthanized by the end of study.

DISCUSSION

Cleavable linkers with excellent in vivo stability and broad applicability are the holy grail in the field of drug delivery. Although various ADC linkers have been developed to date, either ADC efficacy or safety profile has been suboptimal in many cases. The use of stable, non-cleavable linkers (i.e., linkers without a defined cleavage mechanism) is a substantial option for avoiding premature linker cleavage. While some ADC payloads exhibit high potency irrespective of linker cleavage (e.g., MMAF)(36), many payloads require conjugation via cleavable linkers to exert full potential [e.g., MMAE, duocarmycins, and pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimers (PBDs)](36–38). These studies suggest that any residual functional group resulting from linker cleavage can lower the potency of such payloads, highlighting the necessity of traceless payload release. Incorporating a defined linker cleavage site is also crucial to ensure that such payloads can effectively exert the bystander effect upon intracellular release. However, the use of ADCs with cleavable linkers such as VCit often entails an increased risk of adverse effects and low tolerability caused by undesired payload release prior to reaching cancer milieu(21,36,39). Indeed, previous studies have reported that most VCit MMAE-based ADCs and similar conjugates at 10–40 mg kg–1 show dose-limiting hepatotoxicity in rodents(40–42). Linkers developed recently (e.g., β-glucuronide-based linkers(26,43)) may have the capacity to address this dilemma with their unique payload release mechanisms(22,44). However, the applicability of those linkers to a broad range of cancer types has not yet been fully validated. For instance, the expression level of β-glucuronidase in tumor cells has been shown to vary substantially(45). As such, the payload release efficiency and therapeutic efficacy of β-glucuronide linker-based ADCs can be limited depending on the catabolic profiles of target tumors(26,43).

This study demonstrates that the EGCit and structurally similar linkers (e.g., DGCit, EGQ, EGA) could potentially provide a general solution to circumvent clinical safety issues with their excellent in vivo stability against multiple degradation events, without losing the capability of traceless payload release. We have found that our previous EVCit linker is sensitive to human neutrophil protease-mediated degradation like conventional VCit linkers. We have identified that the P2 valine within the VCit linker provokes degradation mediated by human neutrophil proteases. Additionally, we have shown that replacing the valine with glycine effectively protects the linker from this degradation. Compared to VCit-based linkers, the EGCit linker also showed significantly decreased hydrophobicity and increased stability in mouse, monkey, and human plasma. In addition, our EGCit-based ADCs exhibited antigen-specific cytotoxicity comparable to that of conventional VCit and our previous EVCit variants in various cancer cell lines with different metabolic profiles. Along with the remarkable tumor suppression efficacy observed for various mAb–payload combinations in multiple refractory breast and brain tumor models, these findings demonstrate the broad applicability of our cleavable EGCit linker technology. Incorporating a hydrophobic amino acid such as valine at the P2 position has been commonly thought to be important to enable rapid cathepsin B-mediated linker cleavage(46,47). However, our results indicate that such linker design is not a prerequisite to enable traceless payload release rapidly enough to maximize overall in vivo efficacy. Indeed, we have confirmed that most MMAE molecules conjugated via EGCit linkers are released in KPL-4 cells in a traceless manner within 24 h. Recent reports have also demonstrated that the structural or stereochemical alteration to the P2 amino acid does not necessarily abrogate intracellular cleavage of similar ADC linkers due to the potential involvement of other cathepsins(37,48). Based on these and our findings, we speculate that proteases other than cathepsin B also play a role in traceless payload release from the EGCit linker. Although not yet performed, in-depth mechanistic studies will clarify how the interplay of proteases contribute to intracellular cleavage of the unconventional EGCit sequence.

Attenuating antigen-independent toxicities is a challenge not only for VCit-based ADCs but also for other ADCs, regardless of linker type and cleavability. In addition to neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, hepatotoxicity is another common adverse effect that can lead to dose delays or discontinuation of treatment in severe cases. For example, 15–24% of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer treated with Kadcyla® (containing a non-cleavable linker) and Enhertu® (containing a cleavable tetrapeptide linker) showed increases in liver damage-associated enzymes, namely ALT and AST(49,50). As was the case with Mylotarg® (an anti-CD33 maytansinoid ADC with a disulfide cleavable linker)(51), XMT-1522/TAK-522 (an anti-HER2 ADC highly loaded with an auristatin analog via a labile ester linker)(52), and MEDI4276 (an anti-HER2 biparatopic ADC equipped with tubulysin via a cleavable lysine linker)(53), severe liver toxicity can be a reason for clinical hold, study discontinuation, or withdrawal from the market. The exploratory toxicology studies presented here suggest that our EGCit cleavable linker minimally contributes to the risk of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and hepatotoxicity; healthy mice tolerated a single bolus dose of our anti-HER2 EGCit MMAE ADC at 80 mg kg–1 without exhibiting significant changes in hematological parameters or liver tissue integrity. Based on the concept of allometric scaling, this dose level in mice is deemed equivalent to 6.5 mg kg–1 in humans (calculated with a conversion factor of 12.3)(54). Considering this, the tolerability of this ADC in humans may be higher than that of many ADCs currently available in the clinic (for instance, the MTD of Kadcyla® in humans is 3.6 mg kg–1). However, in-depth pharmacokinetics and toxicology studies in other models, in particular non-human primates (i.e., models expressing target antigens in normal tissues), remain to be performed for further validation. In addition, testing ADCs with the same payload/DAR and different linkers will help better understand the advantages of EGCit-based ADCs. Such efforts will also provide more clinically relevant toxicology data (including antigen-dependent toxicity) and insights into the risk of side effects, including ones that were not evaluated in this study (e.g., peripheral neuropathy)(55).

In summary, our findings support the conclusion that the cleavable EGCit linker has the potential to substantially broaden ADC therapeutic window. Because of its structural simplicity, desirable physicochemical properties, and independence from conjugation modality and payload type, this linker technology may be preferred for a variety of ADCs and other targeted drug delivery systems. However, it is important to note that the linker is not the only component determining therapeutic window; target antigen, mAb structure, payload type, payload loading rate, and conjugation method can also impact ADC efficacy and toxicity profiles. In our case, both the aglycosylated parent mAbs and our homogeneous conjugation may have played a role in minimizing overall toxicity by reducing uptake by immune cells and the liver. Therefore, any new ADC should be carefully designed by considering all these parameters. With comprehensive molecular design optimization, we believe that the EGCit linker technology will help expand the repertoire of effective, safe targeted drug delivery systems; this may provide clinicians and cancer patients with access to otherwise unrealistic treatment options such as high-dose ADC therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM138264 to K.T.), the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-19-1-0598 to K.T.), the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP150551 and RP190561 to Z.A.), the Welch Foundation (AU-0042-20030616 to Z.A.), and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (postdoctoral fellowship to Y.A.). We gratefully acknowledge the following researchers for providing the cell lines used in this study: U87ΔEGFR from Prof. Balveen Kaur (UTHealth) and KPL-4 from Dr. Junichi Kurebayashi (Kawasaki Medical School). We thank Prof. Momoko Yoshimoto (UTHealth) for providing a scientific advice on studies using human HSPCs, and Dr. Yoshihiro Otani and Dr. Kyotaro Ohno (Okayama University) for providing a clinical opinion for MRI and liver tissue analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement

Y.A., C.M.Y., N.Z., Z.A., and K.T. are named inventors on patent applications relating to the work (PCT/US2018/034363, US-2020-0115326-A1, EU18804968.8-1109/3630189). S.Y.Y.H., Y.A., C.M.Y., N.Z., Z.A., and K.T. are named inventors on a pending patent application relating to the work. All patent applications were filed by the Board of Regents of the University of Texas System. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drago JZ, Modi S, Chandarlapaty S. Unlocking the potential of antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. Nature Publishing Group; 2021;18:327–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khongorzul P, Ling CJ, Khan FU, Ihsan AU, Zhang J. Antibody–Drug Conjugates: A Comprehensive Review. Mol Cancer Res. American Association for Cancer Research; 2020;18:3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehar SM, Pillow T, Xu M, Staben L, Kajihara KK, Vandlen R, et al. Novel antibody–antibiotic conjugate eliminates intracellular S. aureus. Nature. Nature Publishing Group; 2015;527:323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang RE, Liu T, Wang Y, Cao Y, Du J, Luo X, et al. An Immunosuppressive Antibody–Drug Conjugate. J Am Chem Soc. American Chemical Society; 2015;137:3229–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esnault C, Schrama D, Houben R, Guyétant S, Desgranges A, Martin C, et al. Antibody-drug conjugates as an emerging therapy in oncodermatology. Cancers (Basel). MDPI AG; 2022;14:778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bargh JD, Isidro-Llobet A, Parker JS, Spring DR. Cleavable linkers in antibody-drug conjugates. Chem Soc Rev. Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC); 2019;48:4361–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuchikama K, An Z. Antibody-drug conjugates: recent advances in conjugation and linker chemistries. Protein Cell. 2018;9:33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang H, Liu Y, Yu Z, Sun M, Lin L, Liu W, et al. The Analysis of Key Factors Related to ADCs Structural Design. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C, Corvaïa N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody–drug conjugates. Nat Rev Drug Discov. Nature Publishing Group; 2017;16:315–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz J, Janik JE, Younes A. Brentuximab Vedotin (SGN-35). Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6428–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deeks ED. Polatuzumab Vedotin: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2019;79:1467–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang E, Weinstock C, Zhang L, Charlab R, Dorff SE, Gong Y, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Enfortumab Vedotin for Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:922–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee A. Loncastuximab Tesirine: First Approval. Drugs. 2021;81:1229–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong DS, Concin N, Vergote I, de Bono JS, Slomovitz BM, Drew Y, et al. Tisotumab Vedotin in Previously Treated Recurrent or Metastatic Cervical Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. AACR; 2020;26:1220–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott LJ. Brentuximab Vedotin: A Review in CD30-Positive Hodgkin Lymphoma. Drugs. 2017;77:435–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, Ansell SM, Rosenblatt JD, Savage KJ, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2183–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nademanee A, Sureda A, Stiff P, Holowiecki J, Abidi M, Hunder N, et al. Safety analysis of brentuximab vedotin from the phase III AETHERA trial in Hodgkin lymphoma in the post-transplant consolidation setting. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. Elsevier BV; 2018;24:2354–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson M, El-Khoueiry A, Hafez N, Lakhani N, Mamdani H, Rodon J, et al. Phase I, First-in-Human Study of the Probody Therapeutic CX-2029 in Adults with Advanced Solid Tumor Malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res 2021. page 4521–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anami Y, Yamazaki CM, Xiong W, Gui X, Zhang N, An Z, et al. Glutamic acid–valine–citrulline linkers ensure stability and efficacy of antibody–drug conjugates in mice. Nat Commun. Nature Publishing Group; 2018;9:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorywalska M, Dushin R, Moine L, Farias SE, Zhou D, Navaratnam T, et al. Molecular Basis of Valine-Citrulline-PABC Linker Instability in Site-Specific ADCs and Its Mitigation by Linker Design. Mol Cancer Ther. AACR; 2016;15:958–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao H, Gulesserian S, Malinao MC, Ganesan SK, Song J, Chang MS, et al. A potential mechanism for ADC-induced neutropenia: Role of neutrophils in their own demise. Mol Cancer Ther. American Association for Cancer Research (AACR); 2017;16:1866–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller JT, Vitro CN, Fang S, Benjamin SR, Tumey LN. Enzyme-Agnostic Lysosomal Screen Identifies New Legumain-Cleavable ADC Linkers. Bioconjug Chem. American Chemical Society; 2021;32:842–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu Z, Thorpe M, Akula S, Chahal G, Hellman LT. Extended Cleavage Specificity of Human Neutrophil Elastase, Human Proteinase 3, and Their Distant Ortholog Clawed Frog PR3—Three Elastases With Similar Primary but Different Extended Specificities and Stability [Internet]. Frontiers in Immunology. 2018. Available from: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anami Y, Tsuchikama K. Transglutaminase-Mediated Conjugations. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2078:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anami Y, Xiong W, Gui X, Deng M, Zhang CC, Zhang N, et al. Enzymatic conjugation using branched linkers for constructing homogeneous antibody–drug conjugates with high potency. Org Biomol Chem. Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC); 2017;15:5635–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyon RP, Bovee TD, Doronina SO, Burke PJ, Hunter JH, Neff-LaFord HD, et al. Reducing hydrophobicity of homogeneous antibody-drug conjugates improves pharmacokinetics and therapeutic index. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:733–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao H, Gulesserian S, Ganesan SK, Ou J, Morrison K, Zeng Z, et al. Inhibition of Megakaryocyte Differentiation by Antibody–Drug Conjugates (ADCs) is Mediated by Macropinocytosis: Implications for ADC-induced Thrombocytopenia. Mol Cancer Ther. American Association for Cancer Research; 2017;16:1877–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yardley DA, Krop IE, LoRusso PM, Mayer M, Barnett B, Yoo B, et al. Trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1) in Patients With HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Previously Treated With Chemotherapy and 2 or More HER2-Targeted Agents: Results From the T-PAS Expanded Access Study. Cancer J. 2015;21:357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poon KA, Flagella K, Beyer J, Tibbitts J, Kaur S, Saad O, et al. Preclinical safety profile of trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1): mechanism of action of its cytotoxic component retained with improved tolerability. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;273:298–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamazaki CM, Yamaguchi A, Anami Y, Xiong W, Otani Y, Lee J, et al. Antibody-drug conjugates with dual payloads for combating breast tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambert JM, Chari RVJ. Ado-trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1): An Antibody–Drug Conjugate (ADC) for HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. J Med Chem. American Chemical Society; 2014;57:6949–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okamoto H, Oitate M, Hagihara K, Shiozawa H, Furuta Y, Ogitani Y, et al. Pharmacokinetics of trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd), a novel anti-HER2 antibody-drug conjugate, in HER2-positive tumour-bearing mice. Xenobiotica. 2020;50:1242–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips AC, Boghaert ER, Vaidya KS, Mitten MJ, Norvell S, Falls HD, et al. ABT-414, an Antibody–Drug Conjugate Targeting a Tumor-Selective EGFR Epitope. Mol Cancer Ther. American Association for Cancer Research; 2016;15:661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamblett KJ, Kozlosky CJ, Siu S, Chang WS, Liu H, Foltz IN, et al. AMG 595, an anti-EGFRvIII antibody-drug conjugate, induces potent antitumor activity against EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastoma. Mol Cancer Ther. American Association for Cancer Research (AACR); 2015;14:1614–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staben LR, Koenig SG, Lehar SM, Vandlen R, Zhang D, Chuh J, et al. Targeted drug delivery through the traceless release of tertiary and heteroaryl amines from antibody–drug conjugates. Nat Chem. Nature Publishing Group; 2016;8:1112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doronina SO, Mendelsohn BA, Bovee TD, Cerveny CG, Alley SC, Meyer DL, et al. Enhanced activity of monomethylauristatin F through monoclonal antibody delivery: effects of linker technology on efficacy and toxicity. Bioconjug Chem. American Chemical Society (ACS); 2006;17:114–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caculitan NG, Chuh JDC, Ma Y, Zhang D, Kozak KR, Liu Y, et al. Cathepsin B Is Dispensable for Cellular Processing of Cathepsin B-Cleavable Antibody–Drug Conjugates [Internet]. Cancer Research. 2017. page 7027–37. Available from: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-17-2391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang D, Le H, Cruz-Chuh JD, Bobba S, Guo J, Staben L, et al. Immolation of p-Aminobenzyl Ether Linker and Payload Potency and Stability Determine the Cell-Killing Activity of Antibody–Drug Conjugates with Phenol-Containing Payloads. Bioconjug Chem. American Chemical Society; 2018;29:267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alley SC, Benjamin DR, Jeffrey SC, Okeley NM, Meyer DL, Sanderson RJ, et al. Contribution of linker stability to the activities of anticancer immunoconjugates. Bioconjug Chem. American Chemical Society (ACS); 2008;19:759–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doronina SO, Toki BE, Torgov MY, Mendelsohn BA, Cerveny CG, Chace DF, et al. Development of potent monoclonal antibody auristatin conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:778–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyon RP, Setter JR, Bovee TD, Doronina SO, Hunter JH, Anderson ME, et al. Self-hydrolyzing maleimides improve the stability and pharmacological properties of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Biotechnol. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2014;32:1059–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S, Zhou D, Zheng C, Xiong P, Zhu W, Zheng D. Preclinical evaluation of a novel antibody-drug conjugate targeting DR5 for lymphoblastic leukemia therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics. Elsevier BV; 2021;21:329–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chuprakov S, Ogunkoya AO, Barfield RM, Bauzon M, Hickle C, Kim YC, et al. Tandem-Cleavage Linkers Improve the In Vivo Stability and Tolerability of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 2021;32:746–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su Z, Xiao D, Xie F, Liu L, Wang Y, Fan S, et al. Antibody-drug conjugates: Recent advances in linker chemistry. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:3889–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gregson SJ, Barrett AM, Patel NV, Kang G-D, Schiavone D, Sult E, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer antibody-drug conjugates with dual β-glucuronide and dipeptide triggers. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;179:591–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson JJ, Meares CF. Cathepsin substrates as cleavable peptide linkers in bioconjugates, selected from a fluorescence quench combinatorial library. Bioconjug Chem. American Chemical Society (ACS); 1998;9:618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubowchik GM, Firestone RA, Padilla L, Willner D, Hofstead SJ, Mosure K, et al. Cathepsin B-labile dipeptide linkers for lysosomal release of doxorubicin from internalizing immunoconjugates: model studies of enzymatic drug release and antigen-specific in vitro anticancer activity. Bioconjug Chem. American Chemical Society (ACS); 2002;13:855–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salomon PL, Reid EE, Archer KE, Harris L, Maloney EK, Wilhelm AJ, et al. Optimizing Lysosomal Activation of Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) by Incorporation of Novel Cleavable Dipeptide Linkers. Mol Pharm. 2019;16:4817–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan H, Endo Y, Shen Y, Rotstein D, Dokmanovic M, Mohan N, et al. Ado-trastuzumab emtansine targets hepatocytes via human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 to induce hepatotoxicity. Mol Cancer Ther. American Association for Cancer Research (AACR); 2016;15:480–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Modi S, Park H, Murthy RK, Iwata H, Tamura K, Tsurutani J, et al. Antitumor Activity and Safety of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients With HER2-Low-Expressing Advanced Breast Cancer: Results From a Phase Ib Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1887–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang ES, Baron J. Management of toxicities associated with targeted therapies for acute myeloid leukemia: when to push through and when to stop. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. American Society of Hematology; 2020;2020:57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mersana Therapeutics, Inc. Mersana Therapeutics Announces Partial Clinical Hold for XMT-1522 Clinical Trial [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2021 Dec 15]. Available from: https://ir.mersana.com/news-releases/news-release-details/mersana-therapeutics-announces-partial-clinical-hold-xmt-1522

- 53.Pegram MD, Hamilton EP, Tan AR, Storniolo AM, Balic K, Rosenbaum AI, et al. First-in-Human, Phase 1 Dose-Escalation Study of Biparatopic Anti-HER2 Antibody-Drug Conjugate MEDI4276 in Patients with HER2-positive Advanced Breast or Gastric Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2021;20:1442–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nair AB, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm. Medknow; 2016;7:27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahalingaiah PK, Ciurlionis R, Durbin KR, Yeager RL, Philip BK, Bawa B, et al. Potential mechanisms of target-independent uptake and toxicity of antibody-drug conjugates. Pharmacol Ther. Elsevier BV; 2019;200:110–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings in this study are available within the paper, its supplementary Data file, or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.