Abstract

The vast majority of women who experience physical intimate partner violence (IPV) will likely suffer a brain injury (BI) as a result of the abuse. Accurate screening of IPV–BI can ensure survivors have access to appropriate health care and other supports, but screening results may also impact them receiving fair and equitable treatment in the legal system, and the justice they deserve. We used semi-structured interviews, combined with a contrastive vignette that described a realistic but hypothetical scenario involving IPV with or without BI, to explore the impact of BI on parenting disputes. Participants were lawyers (n = 12) whose focus is family law. Results highlight the potential adverse consequences of a positive BI screen that are influenced by the legal responsibility of counsel, the legal aid status of the woman, ongoing family dynamics, and the expectations of society while the focus on the best interests of the child is retained. Taken together, the findings reflect the legal vulnerability of women in decision-making about their capacity to parent after a BI. We conclude with recommendations for the future of IPV–BI screening aimed at mitigating risk and equipping women to navigate a legal system that has disadvantaged them, both historically and in the current context.

Keywords: neuroscience, protection of research subjects, ethics

I. INTRODUCTION

One in three women will experience intimate partner violence (IPV) in their lifetime.1 Of those who experience physical IPV, up to 92% may suffer a brain injury (BI) as a result of trauma to the head or hypoxia via strangulation.2 BI ranges in severity from mild trauma (mTBI) or concussion, characterized by transient symptoms affecting mental processes such as memory and executive function, to moderate and severe BI resulting in disorders of consciousness lasting days to years.3 IPV–BI is often complicated by neurologic and mental health comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorder.4 Although the increasing awareness of BI in the general population associated with falls, motor vehicle accidents, and sport injuries has led to increased availability of rehabilitation services through public health care systems,5 women who have experienced IPV remain clinically underserved.6 A lack of training and education about BI for frontline health care providers and shelter staff, and a lack of specialized rehabilitation programs tailored to the complexities of IPV–BI are major contributing factors to this gap.7

Research on BI in the context of IPV specifically is in its infancy, and clinical screening relies on tools such as the HELPS Brain Injury Screening Tool,8 diagnostic interviews such as the Boston Assessment of TBI-Lifetime 9 and currently unvalidated questionnaires such as the Brain Injury Severity Assessment (BISA).10 Combining such screening with objective assessments of brain dysfunction using approaches such as blood-based biomarkers or state-of-the-art neuroimaging holds great promise for better precision in confirming or ruling out BI due to IPV.11 Nonetheless, any type of screening in complex psychosocial contexts such as IPV is controversial as the potential benefits are challenged by possible harms from the outcome of the process.12 As such, two criteria must be met to justify screening: (i) the likelihood of a positive result will be significant; and (ii) the availability of an evidence-based validated treatment or intervention in response.13 In the absence of either, the ethics of screening come into question as the benchmark of beneficence is not met. In the context of IPV–BI, implementing screening procedures must be evaluated against concerns about confidentiality, psychological distress, and lack of well-defined and predictable outcomes including possible legal implications.14

Family law traditionally discriminates against women. The system was constructed upon patriarchal values and ideologies that have led to discrepancies in standards of expected behaviors for women and men.15 Given this context, findings of IPV–BI and the comorbid mental health disorders that often accompany an acute injury may be used by abusers and legal counsel to argue for a parenting arrangement that may remove a child from the care of the mother or allow for abuse or coercive control by the abuser to continue. This history, combined with the importance of screening and possibilities for accurate IPV–BI diagnosis in the future, prompts analysis of an evolving ethics landscape in both clinical medicine and research that is even more complex than before. In this paper, we applied a combination of feminist and consequentialist ethics to offer pragmatic recommendations to mitigate possible legal repercussions of BI diagnoses in women who have experienced IPV.

II. METHODS

II.A. Participants and Recruitment

Participants in family law were recruited to this study through snowball sampling among the professional networks of legal scholars and community advocates in British Columbia and Ontario, Canada, and by direct contact with practicing lawyers in these provinces. They were contacted in March and April 2021 by email. We sought to have a diverse representation of gender, race, and age within the participant pool. Participants were family lawyers but were not required to have had experience with IPV or BI to be interviewed. Names and other identifying information have been removed to maintain confidentiality.

II.B. Data Collection

Approximately 1-h long, semi-structured interviews coupled with a minimally contrastive vignette16 were conducted through a secure UBC licensed Zoom account. Table 1 provides examples of the questions that guided the conversation. The vignette, situated between the interview questions, provided hypothetical information about the ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, age, employment status, mental health, history of substance use, family situation, legal history, physical health status, and IPV history of a client. The minimally contrasting detail between the two conditions was the existence of a BI resulting from IPV (Table 2). The vignette was developed and tested by vetting iterations until the research team reached consensus it contained sufficient information to provide lawyers with a basis to discuss legal knowledge and strategy. The vignette conditions were presented in the same order to each participant—first the vignette without, and then the vignette with, BI. All participants responded to questions about both conditions of the vignette and were asked to imagine themselves as the counsel for the alleged abuser for the condition specifying BI. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Table 1.

Examples of interview questions

| How often do your cases involve IPV? What effect does the presence of IPV have on your initial evaluation of a case or development of your strategy for a parenting dispute? Can you walk me through your initial thoughts on this hypothetical client? What information from this vignette would you prioritize in your strategy for a parenting dispute? What impact does a woman’s mental health diagnosis have in parenting disputes? What impact would a BI have in parenting disputes? How would your strategy change if you were the counsel for the father/alleged abuser? |

Table 2.

Contrastive vignette

| Condition | Client information |

|---|---|

| No BI present | Client A lives in North Vancouver, she is 37 years old, white, and a stay-at-home mom. She is married and together with her partner they have two children, aged 8 and 10. Client A recently fled the home with her two children to a women’s shelter because she had experienced repeated episodes of IPV. Client A has been taking anti-depressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) for 18 months for diagnosed major depressive disorder. Client A approaches your office expressing her desire for full custody of both children. |

| BI as a result of IPV | Client B lives in North Vancouver, she is 37 years old, white, and a stay-at-home mom. She is married and together with her partner they have two children, aged 8 and 10. Client B recently fled the home with her two children to a women’s shelter because she had experienced repeated episodes of IPV. Client B has been taking anti-depressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) for 18 months for diagnosed major depressive disorder and has recently been diagnosed with a traumatic BI (concussion). The concussion is linked to and likely caused by one of the incidents of IPV. Her depression has significantly worsened since her concussion. Client B approaches your office expressing her desire for full custody of both children. |

The protocol was approved by the ethics board at the University of British Columbia—Okanagan (H20–03745). All participants provided written and verbal informed consent.

II.C. Data Analysis

We used a constructivist grounded theory approach to code and analyze the data.17 In particular, we allowed for themes to emerge from the data rather than beginning with preconceived ideas or categories. For each interview transcription, author QB coded the data in three phases: (a) open coding to derive holistic and conceptual emergent themes of the conversations and knowledge provided by the participants, (b) focused coding for more specific context related to IPV–BI, and (c) axial coding to identify categories and subcategories for data from the previous two steps. Feminist ethics provided the principles to guide the analysis as it pertains to the gendered nature of IPV–BI, and centers the experiences of women; consequentialist principles provided a framework for analysis to assess the ethical status of actions based on their consequences; and, the pragmatic neuroethics lens provided the framework for solution-oriented recommendations.18 Quotes are provided to illustrate and provide richness to the themes. Ellipses are applied for readability.

III. RESULTS

Twelve participants (9 women; 3 men) took part in the study (Table 3). On average, 56% of their legal cases involve some form of physical, psychological, emotional, financial, or some combination of IPV (range: 25–100% of cases). For three participants, violence against women was either the primary or sole focus of their practice.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Variable | Total (Range) |

|---|---|

| Gender a (n = 12) | |

| Man | 3 |

| Woman | 9 |

| Age (M, range) | 46.3 (29–66) |

| Race a (n = 12) | |

| White | 11 |

| Indigenous | 1 |

| Years of practice (M, range) | 12.3 (2–28) |

| 0–5 | 2 |

| 6–10 | 3 |

| 11–15 | 5 |

| 16–20 | 0 |

| 21–25 | 1 |

| 26–30 | 1 |

| Province of practice | |

| British Columbia | 4 |

| Ontario | 8 |

aParticipants were asked to self-identify.M: mean

III.A. Open and Focused Coding Results—Major Themes

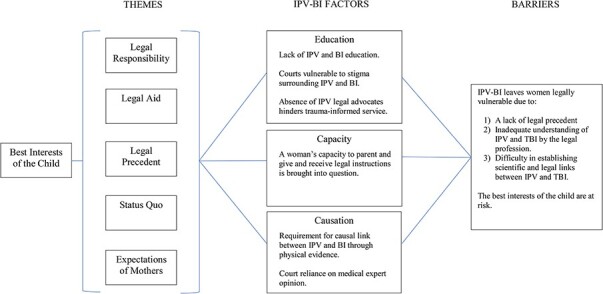

Five general themes applicable to family law, and three factors specific to IPV–BI were identified. Figure 1 shows the interactions and the connection of the themes and factors to the overarching goal of the Canadian family law system to act in the best interest of the child.

Figure 1.

Conceptual representation of general themes, IPV–BI specific factors, and resulting barriers.

III.B. Theme 1: Legal Responsibility

All participants discussed legal responsibility and how it shapes the way they present facts to the judiciary. They emphasized their legal responsibility to the client and their best interests in the face of accusations of physical violence causing BI:

009 (W; 9 years in practice (YIP); legal aid focused): […] my job is to represent my client. And at the end of the day if a judge makes the decision that I’m hoping that they’ll make that means that I’ve done my job.

However, half of the participants provided a disclaimer they would avoid representing accused abusers due to the pressures imposed by the professional legal responsibility to advocate for a client accused of morally reprehensible actions:

010 (W; 28 YIP; IPV focused): This [the legal responsibility] is why I don’t, I’ve never represented abusers. Nonetheless, my client tells me [they didn’t abuse their partner], and my obligation is to believe my client.

III.C. Theme 2: Impact of Legal Aid Certificates

All participants also discussed the impact of legal aid certificates. Each Canadian province has a program that provides legal aid certificates to those who are eligible. These certificates enable clients to seek counsel they otherwise would be unable to access due to financial constraints. Lawyers bill to and are paid directly by the legal aid program; there is no cost to clients. The reported impact of legal aid certificates involved constraints imposed by the legal aid system, including insufficient funding resulting in unpaid work, lack of IPV-informed lawyers willing to accept legal aid files, strict client eligibility requirements, and restrictions on tasks for which compensation is permitted. Participants emphasized the significance of these barriers when working with clients with mental health needs, substance use, high conflict situations, and poverty:

001 (W; 14 YIP; IPV focused): Everybody’s looking for legal aid lawyers but nobody can find them because nobody’s taking the certificates. It’s very, very hard to find lawyers who will take aid and certainly difficult to find ones that know anything about violence against women who will take legal aid.

III.D. Theme 3: Legal Precedent for Decision-Making

All participants also discussed a third major theme: the importance of legal precedent and the presence of case law that informs the decisions of judges. Participants emphasized with new topics, such as IPV–BI where there is no case law, decisions are particularly susceptible to the subjective perspective of judges and their understanding of the situation. This is especially problematic given when a judge is called to the bench, they make judgments on cases in all contexts, not just the specialization of their career as a lawyer:

009: I’d say for the most part their decisions are almost entirely based on case law and precedent. But then that’s where the subjective factors come in, where whatever evidence has been laid out in that trial, can sway a judge to do one thing or another or deviate from what the case law says.

008 (W; 5 YIP): I’m not sure that the judges really have the information and understand at this point what all is involved in strangulation or traumatic brain injury.

All participants acknowledged the current construction of family law significantly relies on legal precedent in decision-making. Therefore, as participants explained, the absence of such legal precedent limits the ability of the system to appropriately address new issues such as IPV–BI.

III.E. Theme 4: Family Dynamics

Given a setting in which the family law system acts in the best interests of the child, participants explained judges prefer to keep both parents involved. All participants reported judges will prioritize dual parent involvement despite a history of IPV over disrupting the status quo and a child’s routine.

III.F. Theme 5: Expectations of Mothers

Participants described the difference in expectations of women compared with men relating to health and parenting styles. Ten participants recounted specific experiences where mental health diagnoses or substance use issues for fathers were dismissed as irrelevant, whereas the same diagnoses in women would garner intense scrutiny and investigation:

001: ...any tiny little thing that is raised about a woman’s parenting is somehow completely under the spotlight, where he [the father] is actively engaging in behavior that is highly problematic...

010: I think a lot of judges, […] would be more concerned that a mother who they would see as the primary nurturer might have an illness that would affect her ability to parent.

III.G. Axial Coding Results—IPV–BI Specific Factors

(i) Factor 1: IPV and BI education

All participants reported a lack of education about IPV in law school. They received relevant training through continuing professional development seminars about IPV, including information about how lawyers can properly advocate for, and work with, survivors of abuse, or acquired information through media coverage of brain injuries such as concussion and chronic traumatic encephalopathy in collision sports. Some participants reported they had acquired knowledge about BI through undergraduate studies, personal experience, or previous employment in the health sector before beginning a career in law.

Those participants who reported experience in attending and developing specialized domestic violence training for legal professionals (n = 5) noted that judges are not required to have training about IPV. One participant reported a court experience with a judge who appeared to be dismissive of the experience:

002 (W; 12 YIP): but [judges need to display] an understanding and also willingness to really acknowledge it and engage with it, as opposed to just saying, Oh, well, this was, you know, people were behaving in this way or that way while they were together but now they’re separated so we don’t really need to talk about it anymore.

(ii) Factor 2: Capacity of the client

Concerns about a woman’s capacity to parent, and her capacity to give and receive legal instructions due to a BI emerged when participants discussed the vignette with the BI condition:

007 (W; 14 YIP): The other side will basically turn around to say, well... they’ve got a significant brain injury therefore they’re not competent to be able to care for the children.

They reported claims by opposing counsels that IPV–BI renders a woman unfit to parent are absurd, raised the same personal concern about capacity. Some participants even acknowledged their own hypocrisy:

009: (laughing) Okay this is awful. So it depends. There’s not enough information there but if I was representing Dad, depending on what he was saying to me, we might make the claim that mom isn’t mentally stable to have her children in her care. You hear that a lot? Isn’t that bad?

Every participant also expressed concern about the capacity of a client to give and receive legal instructions after a BI:

012 (W; 2 YIP): Perhaps one of the considerations I have to be taking when dealing with someone who's dealing with a brain injury is capacity. Giving instructions, memory, a good solid understanding of what I'm recommending and the implications of that and implications of their choices.

They further noted the importance of receiving medical assessments from a woman’s physician confirming she is capable of participating in the legal processes.

(iii) Factor 3: Causation

Proving or establishing plausible causation between an incident of IPV and a BI emerged as the third factor in the interviews:

005 (W; 5 YIP): […] if the [screening] tool is determining whether the brain injury is a result of intimate partner violence that could be valuable. […] it's a piece of evidence that shows that the violence occurred.

One barrier to establishing causation between IPV and BI is the requirement for direct evidence of assault. All participants emphasized evidence available through physical wounds and witnesses testimony is necessary to surmount this barrier:

012: What sort of violence was she experiencing? … Unless it was really awful, like really awful, I would be saying we're going to have a lot of trouble with this, we're going to need all the evidence we can get.

In these conversations about causation and IPV–BI screening tools, participants also highlighted the importance of the expert opinions of physicians:

004 (W; 11 YIP): I do know that judges tend to defer to the experts, right. So if you had an expert come in and say, I’ve been I spent my life doing this and studying this, and this is the tool and this is how it works. The judges are going to probably defer to that.

However, participants also emphasized the barriers to access of expert opinion or expert evidence on IPV–BI, and in situations where a client is on a legal aid certificate:

010: even if let’s say she's able to afford an expert to come in who can talk about the TBI and talk about why she’s more depressed now and what treatment she’s undergoing for the TBI, but based on what I've learned in the past year, I don't think there's an expert, a TBI expert, who’s able to say 100%, the TBI came from the domestic violence.

IV. DISCUSSION

Through interviews that combined questions about IPV and a contrastive vignette involving BI, we found five themes that represent considerations for lawyers in parenting disputes: (i) legal responsibility, (ii) legal aid certificates, (iii) legal precedent, (iv) family dynamics, and (v) expectations of mothers. Three additional factors elaborate the complexities introduced by IPV–BI and its potential impact on parenting disputes: (a) IPV and BI education, (b) capacity of the client, and (c) causation. These themes and factors operate under and are influenced by the overarching legislation that guides the priority of parenting disputes within an evolving family law system that includes changes to The Divorce Act enacted in March 2021.

Canadian family law professionals aim to act in the best interests of the child and current legislation supports them doing so. Capacity to parent is therefore a factor that often receives significant scrutiny in parenting disputes. Deliberations regarding the capacity to parent have a history of incorporating medical information, questioning a parent’s capacity based on their health status.19 It is important to note although confidentiality laws do apply to physician–patient relationships in Canada, the best interests of the child takes priority, and the confidentiality privilege can be violated. Therefore, current legislation and confidentiality laws surrounding health information leave women vulnerable to health information such as IPV–BI not just being disclosed in a court of law regardless of their preference, but being critically examined and weaponized by opposing counsel. Findings of this study show participants expect counsel for an abuser to use IPV–BI as a way to minimize a mother’s capacity to parent. This is consistent with past uses of medical information such as mental health disorders in parenting disputes involving IPV.20 Although an increased understanding of mental health has now rendered these strategies outdated and unsuccessful in completely stripping mothers of access to her children, these claims are still used to force mothers to engage in psychological examinations at regular intervals (eg every 6 months) to prove she is still capable of parenting her children. Given that the understanding of IPV–BI is in its infancy, women who experience IPV–BI are susceptible to uncertainty and stigma as were women with mental health disorders in the recent past. In addition, the lack of validated diagnostic tools and treatment plans means women are at greater risk of opposing counsel gaining traction with judges who prefer to rely on expert opinion and medical evidence of capacity, and can only be reassured with validated treatments and interventions when health status is called to question. Without an improved and gendered understanding of IPV–BI by those in the legal system, sexist, patriarchal ideologies may continue to perpetuate violence against women through discrepancies in what society considers a capable mother.

IV.A. Ethical Recommendations for Future IPV–BI Screening

The findings of this study suggest IPV–BI adds an additional element to parenting disputes that leaves women legally vulnerable. This vulnerability can be attributed to sexism and the resulting differential views and expectations of women as mothers, the license to violate physician-patient privilege in family law, and pragmatic barriers presented by the lack of legal precedent, inadequate knowledge and awareness of IPV and BI, and the difficulty in establishing physical evidence of causal links between an incident of IPV and the BI. Given these findings, we offer four principled strategies to improve future IPV–BI research and screening (Table 4):

Table 4.

Ethicolegal issues identified and resulting recommendations

| Issue | Ethicolegal recommendation | Action item |

|---|---|---|

| Court reliance on physician testimony | Expert allyship | Proactive involvement of physicians throughout IPV–BI screening. Ensure physicians are aware of all information and willing to advocate in court if necessary. |

| Lack of informed IPV and BI advocacy for women | Establish trauma-informed legal team | Connect participants to legal professionals educated in IPV, IPV–BI, and trauma-informed legal practices. |

| Interpretation of BI and its impact on parenting capacity | Assessment of parenting capacity | Include an assessment of a BI in evaluating parenting capacity with IPV–BI screening tools and resulting reports. |

| Possible indirect harms of participation | Transparency and the right to opt-out | Prioritize transparency before and throughout the screening process to ensure participants know the potential legal implications of screening and diagnostic results and understand their right to opt-out. |

IV.B. Recommendation 1: Expert Allyship

Relationships between organizations screening for IPV–BI and medical experts (ie physicians) should be prioritized. Proactive involvement of trauma and violence-informed physicians streamlines expert testimony in family law cases where IPV–BI is present. Expert allyship is especially important, whereas research teams work to formally validate IPV–BI screening tools. It is important to note although other allied health professionals may have intimate knowledge of an individual’s IPV–BI recovery and functioning, all participants noted physician opinion carries the most significant weight in the current legal system.

IV.C. Recommendation 2: Trauma-Informed Legal Teams

In the absence of an overhaul of the legal curriculum, organizations providing screening and support for women experiencing IPV–BI should establish and provide legal contacts to properly trained experts who can assist with factors pertaining to IPV. This solution involves connecting participants to legal professionals with significant education and experience with the complexities that IPV and BI present within parenting disputes.

IV.D. Recommendation 3: Assessment of Parenting Capacity

Screening tools and assessments for IPV–BI should incorporate a specific assessment of the BI in relation to its impact on the ability to parent. Aside from the obvious benefit for the health of the victim, this would be a means to proactively ensure such information is available for court. It may also prevent intense court-ordered psychological examination processes that often continue at regular intervals once the initial parenting dispute has concluded.21

IV.E. Recommendation 4: Transparency and the Right to Opt-Out

Victims should be made aware of the possible use of IPV–BI information in parenting disputes including, for example, on-line resources such as the ABI Toolkit (https://abitoolkit.ca/service-provision/screening-for-brain-injury/). Transparency about possible legal implications throughout the process of IPV–BI screening upholds autonomy and reinforces the right of an individual to opt-out of a screening process. This is especially important as screening and diagnostics for IPV–BI evolve from questionnaire-based screening to medical imaging and blood biomarker diagnostic tools that may hold great weight in Canadian law. Although opting out may harm a person by removing access to health care and rehabilitation services, the possible legal consequences of IPV–BI screening is the trade-off. Transparency allows for affected individuals to make an informed decision they believe is best for themselves and their children.

These recommendations provide strategies to address the identified barriers presented by inserting IPV–BI into the current construction of Canadian family law. It is important to note these recommendations must be applied using an intersectional lens, and be tailored to each individual with the help of their medical and legal teams. Until the legal and societal systems catch up to the science and sociology behind IPV–BI, these recommendations should be applied to protect women who have experienced IPV–BI from further victimization. We acknowledge more nuanced analyses are necessary to make broad, structural recommendations on how to address patriarchal values ingrained in Canadian family law and build a more just legal system free of discrimination. Nonetheless, the recommendations in this paper address IPV–BI specifically and the current flaws in the legal system in an effort to help combat stigma, sexism, and ignorance, and to aid women in what is a ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’ dilemma.

IV.F. Limitations

Results of this study are transferable but not generalizable. The transferability of the findings in this study can be affected by several factors, including the location in which it was conducted. This study only included participants from the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia in Canada. In addition, although we acknowledge IPV is not an experience exclusive to cis, heterosexual women, the single vignette used in this study depicted women experiencing IPV at the hands of a man. Future studies should be conducted on IPV–BI in same-sex relationships, and with individuals whose gender identity lies outside of the traditional binary. The single vignette also focused on mild trauma only. Different forms and severities of BI can naturally be expected to have varying impacts on both the input to, and outcome of parenting disputes. The pool of participants was small and lacks diversity. We were not able to interrogate the data for gender or cultural differences. Many of the participants also reported a lack of experience with racialized clients or communities and failed to provide insight into this significant aspect of family law.

V. CONCLUSIONS

IPV has historically been minimized or dismissed in Canadian family law.22 The results of the current study suggest IPV still leaves women legally and medically vulnerable. We suggest expert allyship, trauma-informed legal teams, parenting capacity assessments, and transparency about the benefits and harms of opting in or out of screening as pragmatic, principled, and ethical strategies to help remedy the continued victimization of women who have experienced IPV–BI.

FUNDING

This research was supported by the Canadian Department of Women and Gender Equality and an anonymous donor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the participants for their time and expertise as well as Karen Mason and Isabel Grant for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

World Health Organization, 2014.

Jacquelyn C. Campbell et al., The Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Probable Traumatic Brain Injury on Central Nervous System Symptoms, 27 J. Women’sHeal. 761–767 (2018); Gwen Hunnicutt et al., The Intersection of Intimate Partner Violence and Traumatic Brain Injury: A Call for Interdisciplinary Research, 32 J. Fam. Violence 471–480 (2017).

Nicholas D. Schiff & Steven. Laureys, Disorders of Consciousness (2009).

Glynnis Zieman, Ashley Bridwell & Javier F. Cárdenas, Traumatic Brain Injury in Domestic Violence Victims: A Retrospective Study at the Barrow Neurological Institute, 34 J. Neurotrauma 876–880 (2017); Murray B. Stein & Colleen Kennedy, Major Depressive and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Comorbidity in Female Victims of Intimate Partner Violence, 66 J. Affect. Disord. 133–138 (2001); Eve Valera & Howard Berenbaum, Brain Injury in Battered Women, 71 J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 797–804 (2003); Jonathan D. Smirl et al., Characterizing Symptoms of Traumatic Brain Injury in Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence, 33 BrainInj. 1529–1538 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2019.1658129.

R. Brock Frost et al., Prevalence of Traumatic Brain Injury in the General Adult Population: A Meta-Analysis, 40 Neuroepidemiology 154–159 (2013).

Stephen T. Casper & Kelly O’Donnell, The Punch-Drunk Boxer and the Battered Wife: Gender and Brain Injury Research, 245 Soc. Sci. Med. 112688 (2020).

Maria A. Pico-Alfonso et al., The Impact of Physical, Psychological, and Sexual Intimate Male Partner Violence on Women’s Mental Health: Depressive Symptoms, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, State Anxiety, and Suicide, 15 J. Women’sHeal. 599–611 (2006); Blake Nicol et al., Using Behavior Change Theory to Understand How to Support Screening for Traumatic Brain Injuries Among Women Who have Experienced Intimate Partner Violence, 2 Women’sHeal. Reports (NewRochelle, N.Y.) 305–315 (2021); Halina Lin Haag et al., Battered and Brain Injured: Assessing Knowledge of Traumatic Brain Injury Among Intimate Partner Violence Service Providers, 28 J. Womens. Health (Larchmt). 990–996 (2019).

Halina Lin Haag et al., Battered and Brain Injured: Traumatic Brain Injury Among Women Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence – A Scoping Review., Trauma. ViolenceAbuse 1524838019850623 (2019), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31170896 (last visited Jul 5, 2022).

Catherine B. Fortier et al., The Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime Semistructured Interview for Assessment of TBI and Subconcussive Injury Among Female Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence of Research Utility and Validity, J. HeadTraumaRehabil. 37 (2021).

Valera and Berenbaum, supra note 4.

Tara E. Galovski et al., A Multi-Method Approach to a Comprehensive Examination of the Psychiatric and Neurological Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence in Women: A Methodology Protocol, 12 Front. Psychiatry (2021); Jirapat Likitlersuang et al., Neural Correlates of Traumatic Brain Injury in Women Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Structural and Functional Connectivity Neuroimaging Study, 37 J. HeadTraumaRehabil. E30–E38 (2022).

Primavera A. Spagnolo & David Goldman, Neuromodulation Interventions for Addictive Disorders: Challenges, Promise, and Roadmap for Future Research, 140 Brain 1183–1203 (2017).

Victoria J. Palmer, Jane S. Yelland & Angela J. Taft, Ethical Complexities of Screening for Depression and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Intervention Studies, 11 BMC PublicHealth (2011); Kristin D. McLaughlin, Ethical Considerations for Clinicians Treating Victims and Perpetrators of Intimate Partner Violence, 27 EthicsBehav. 43–52 (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1185012; Nikita Arora et al., We Should Routinely Screen for Domestic Violence (Intimate Partner Violence) in the Emergency Department, 21 Can. J. Emerg. Med. 701–705 (2019).

Palmer, Yelland, and Taft, supra note 13.

Peter G. Jaffe, Claire V. Crooks & Samantha E. Poisson, Common Misconceptions in Addressing Domestic Violence in Child Custody Disputes, 54 Juv. Fam. Court J. 57–67 (2003); Suzanne Zaccour, Crazy Women and Hysterical Mothers: The Gendered Use of Mental-Health Labels in Custody Disputes, 31 Can. J. Fam. L. 57 (2018); Suzanne Zaccour, Does Domestic Violence Disappear from Parental Alienation Cases? Five Lessons from Quebec for Judges, Scholars, and Policymakers, 33 Can. J. Fam. Law (2020); Donna Martinson & Margaret Jackson, Family Violence and Evolving Judicial Roles: Judges as Equality Guardians in Family Law Cases, 30 Can. J. Fam. Law (2017); Melanie F. Shepard & Annelies K. Hagemeister, Perspectives of Rural Women: Custody and Visitation with Abusive Ex-Partners, 28 J. WomenSoc. Work 165–176 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109913490469.

Kenneth Burstin, Eugene B. Doughtie & Avi Raphaeli, Contrastive Vignette Technique: An Indirect Methodology Designed to Address Reactive Social Attitude Measurement1, 10 J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 147–165 (1980); Laura Y. Cabrera & Peter B. Reiner, A Novel Sequential Mixed-Method Technique for Contrastive Analysis of Unscripted Qualitative Data: Contrastive Quantitized Content Analysis, 47 Sociol. MethodsRes. 532–548 (2018).

Kathy Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis (2006).

Alison M. Jaggar, Feminist Ethics, inTheBlackwellGuide toEthicalTheory 433–460 (2017), http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/b.9780631201199.1999.00022.x (last visited Jun 19, 2021); EricRacine, Pragmatic Neuroethics: Improving Treatment and Understanding of The Mind-Brain (2010).

Zaccour, supra note 15.

Id.; Ashley R. Jutchenko, Parental Mental Illness: The Importance of Requiring Parental Mental Health Evaluations in Child Custody Disputes, 56 Fam. CourtRev. 664–678 (2018).

Jutchenko, supra note 20.

Echo A. Rivera, April M. Zeoli & Cris M. Sullivan, Abused Mothers’ Safety Concerns and Court Mediators’ Custody Recommendations, 27 J. Fam. Violence 321–332 (2012); Jennifer L. Hardesty & Lawrence H. Ganong, How Women Make Custody Decisions and Manage Co-Parenting with Abusive Former Husbands, 23 J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 543–563 (2006); Martinson and Jackson, supra note 15; Jaffe, Crooks, and Poisson, supra note 15.

Contributor Information

Quinn Boyle, School of Health and Exercise Sciences, University of British Columbia Okanagan, Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada; Neuroethics Canada, Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Judy Illes, Neuroethics Canada, Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Deana Simonetto, Department of History and Sociology, University of British Columbia Okanagan, Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada.

Paul van Donkelaar, School of Health and Exercise Sciences, University of British Columbia Okanagan, Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada.