Abstract

Aim

To present a case of rapid onset on neovascular glaucoma following the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Background

COVID-19 has various ocular manifestations such as conjunctivitis, uveitis, retinal vasculitis, and so on. However, to date, the development of neovascular glaucoma has not been reported in COVID-19.

Case description

A 50-year-old male with a history of COVID-19 3 weeks ago presented with left eye (OS) central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) and right eye (OD) cystoid macular edema with disc and microvascular leakage on multimodal imaging. After being managed conservatively for 2 weeks, the patient developed OD neovascular glaucoma with intraocular pressure (IOP) of 44 mm Hg and angle neovascularization (NVA) on gonioscopy. The patient was started on topical antiglaucoma medications (AGM) with panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) and responded well with complete regression of NVA, CME, and normal IOP after 3 weeks.

Conclusion

This is the first reported case of rapid onset of NVG secondary to COVID-19-induced retinal vasculitis. COVID-19-associated prothrombotic state with secondary retinal vascular involvement can potentially trigger such NVG. Such NVG responds well with topical AGM and PRP therapy.

Clinical significance

Given the global COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative to be vigilant regarding the various vision-threatening manifestations associated with the disease such as the NVG.

How to cite this article

Soman M, Indurkar A, George T, et al. Rapid onset Neovascular Glaucoma due to COVID-19-related Retinopathy. J Curr Glaucoma Pract 2022;16(2):136-140.

Keywords: Central retinal artery occlusion, COVID-19, Neovascular glaucoma, Panretinal photocoagulation, Retinal vasculitis

Background

The COVID-19 outbreak caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has affected multiple vascular tissues in the body and the eye is no exception. The infection causes an increase in the inflammatory response, hypoxic damage, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), ultimately leading to arterial and venous thromboembolic ocular disease.1 While various ocular surface diseases, retinal, and optic nerve manifestations have been described with varying severity,2 reports of glaucoma do not exist. We report a case with rapid onset neovascular glaucoma in one eye of a patient otherwise having bilateral retinal vascular pathology.

Case Description

A 50-year-old male with no significant systemic comorbidities presented with complaints of a sudden loss of vision in the left eye of 2 weeks duration. He was earlier diagnosed as a primary angle-closure glaucoma suspect in both eyes and had undergone Yag peripheral iridectomy in both eyes. Three weeks before the symptoms, he was diagnosed positive for COVID-19 by RT-PCR with mild respiratory symptoms requiring hospitalization and recovered without other complications. On examination, the BCVA was 6/6 in the right eye and light perception in the left eye. The intraocular pressure was 20 mm of Hg in both eyes. Anterior segment examination showed bilateral patent peripheral iridotomy and grade 2 RAPD in the left eye. Gonioscopy examination showed an open anterior chamber angle without peripheral anterior synechiae or neovascularization. Dilated fundus evaluation in the right eye was unremarkable except for a dull foveal reflex while the left eye revealed arterial narrowing with faint retinal opacification (Fig. 1). Fundus fluorescein angiography revealed microvasculitis, perifoveal hyperfluorescence, and disc leakage in the right eye suggestive of nonocclusive retinal vasculitis with macular edema and delay in the filling of the retinal arteries with a delayed arteriovenous transit time suggestive of CRAO in the left eye (Figs 2A to D). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed cystoid macular edema with submacular detachment in the right eye and inner retinal atrophy with small subfoveal pigment epithelial detachment in the left eye (Figs 2E and F). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) was normal in the right eye and abnormal in the left eye (Fig. 3). The visual field was recorded in the right eye, which was normal (Fig. 3). He was started on topical steroids in the right eye. Left eye ocular massage was done. He was sent to the physician for a thromboembolic workup including carotid Doppler, routine blood investigations, a workup for coagulopathy including D-Dimer levels and ANA profile, all of which were normal. Two weeks later he presented with significant corneal edema with gonioscopic evidence of angle neovascularization in the right eye (Fig. 4) while the left eye remained so. The intraocular pressure recorded was 44 mm Hg in the right eye and 18 mm Hg left eye. OCT of the right eye however revealed a spontaneous decrease in CME (Fig. 5). The right eye secondary glaucoma was managed with oral Acetazolamide, a topical combination of Brimonidine with Timolol and Dorzolamide followed by pan-retinal photocoagulation. Three weeks after treatment he had well-regressed angle new vessels, normal IOP, and no macular edema in the right eye with 6/6 vision and continues to be on follow-up. The left eye revealed resolved CRAO (PL vision) with normal IOP and no new vessels.

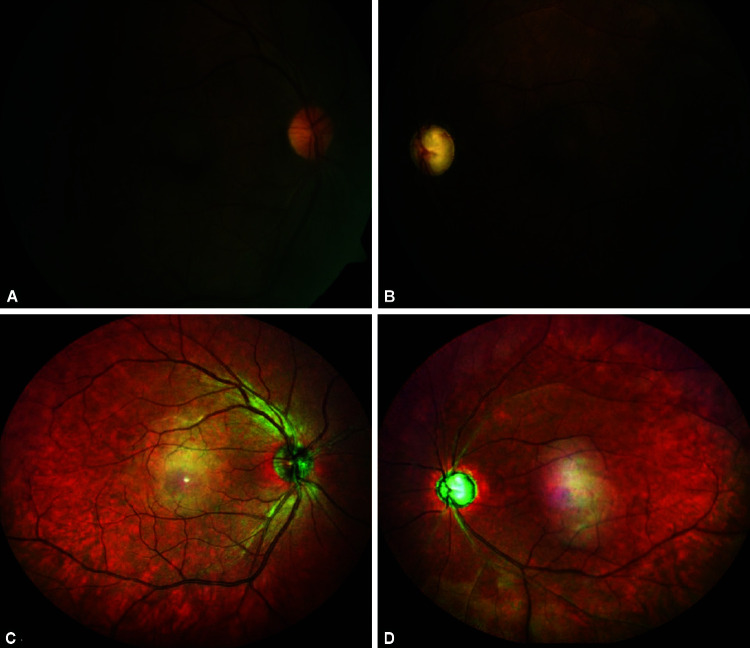

Figs 1A to D.

(A) Clinical photograph showing normal disk in the right eye; (B) Glaucomatous disk in the left eye with attenuated arterioles; (D) Note the altered reflective signals from the ischemic retina (arrow) in the left eye; (C and D) Central ghost maculopathy artifacts (arrowhead) seen on wide-field multicolor imaging in both eyes

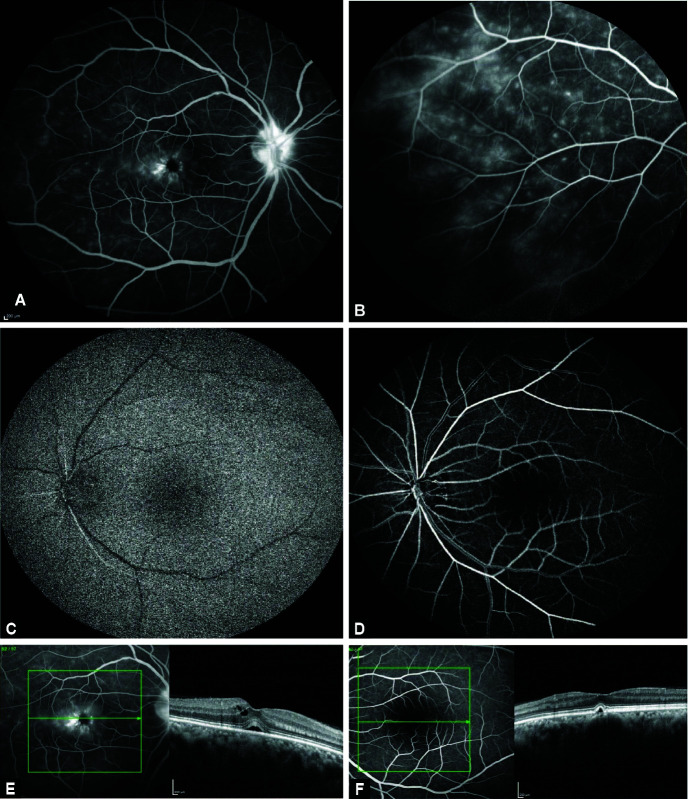

Figs 2A to F.

(A) Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) shows disk leakage, perifoveal leakage; and (B) microvascular leakages in the right eye; and (C) delayed arm retinal; and (D) prolonged arteriovenous transit time in the left eye (E) optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows cystoid macular edema (CME) with submacular detachment in the right eye; and (F) inner retinal minimal reflectivity and atrophy with small pigment epithelial detachment in the left eye

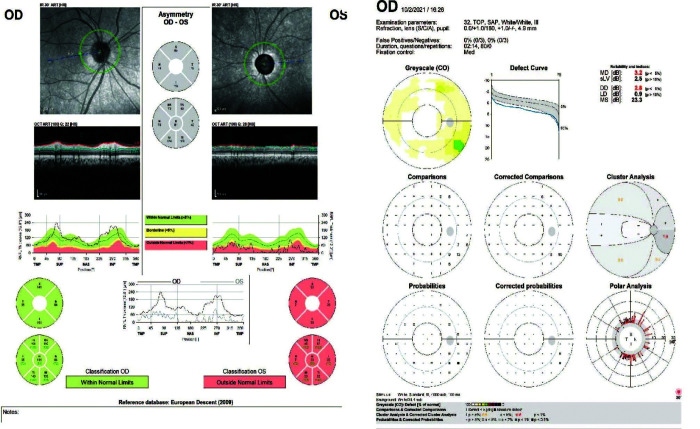

Fig. 3.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) analysis showing normal RNFL in the right eye and abnormal left eye. The right eye octopus 32 field is normal

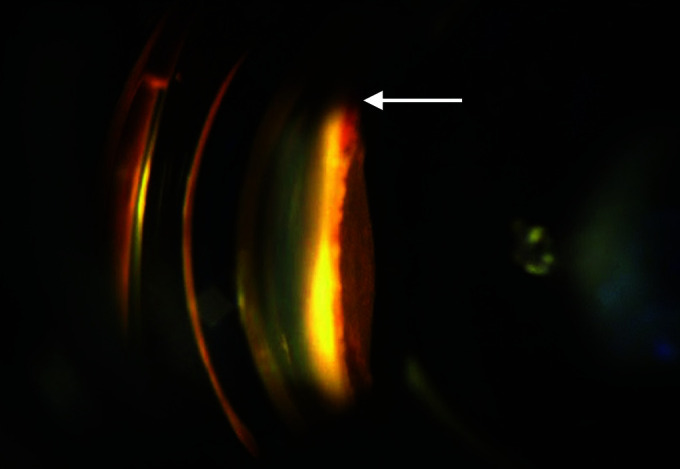

Fig. 4.

Gonioscopy of the right eye revealing neovascularization of the angle (white arrow)

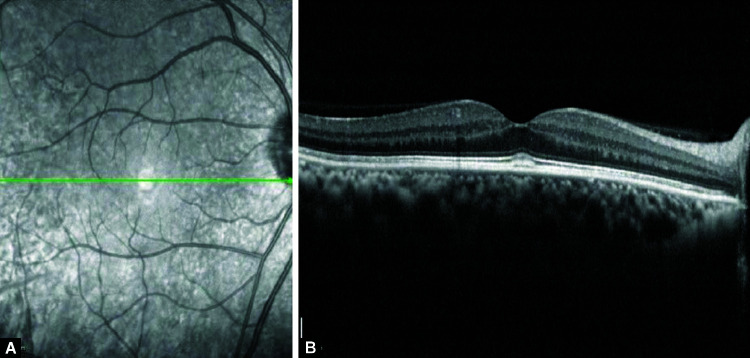

Figs 5A and B.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows resolution of cystoid macular edema (CME) and submacular detachment in the right eye, at last follow-up

Discussion

We report a case of a middle-aged COVID infected male presenting 3 weeks later with two different retinal events and rapid progression to neovascular glaucoma in one eye. To our knowledge, such a rapid onset of secondary glaucoma after COVID related ocular disease has not been reported in the literature to date.

In neovascular glaucoma, exam findings can be subtle, requiring the ophthalmologist to maintain a high index of suspicion of conditions that are commonly associated such as diabetic retinopathy, central retinal vein occlusion, or ocular ischemic syndrome.3,4 Though NVG is associated with iris neovascularization, in entities like ischaemic CRVO rarely, there may be neovascularization of angle without neovascularization of the pupillary border.5 The primary event in NVG is thus a condition leading to retinal hypoxia and ischemia which disrupts the balance between pro-and anti-angiogenic factors, thereby stimulating angiogenesis. Common angiogenic factors include vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs), hepatocyte growth factor, insulin-like growth factor, tumor necrosis factor, and inflammatory cytokines (especially IL-6).6

Ocular involvement in COVID infection may be a direct manifestation of viral infection as seen in ocular surface diseases7,9 and neuritis10,11 while retinal involvement is usually secondary to thrombotic after events or exacerbated inflammatory responses.12,17 COVID-19 infection-induced prothrombotic vascular endothelial microenvironment as a precipitating cause of artery occlusion has been hypothesized. These events occur a few weeks to months after the active viremia stage and may even occur in those who have been started on anticoagulant therapy.15,16 The left eye of this patient probably developed arterial occlusion by this mechanism. Type 3 hypersensitivity with deposition of immune complexes in vessel walls causing autoimmune vasculopathy has also been speculated in some eyes.18 The right eye of the patient probably manifested this form of presentation with microvascular leakages, disk edema, and cystoid macular edema.

Though angiographically the initial presentation appeared not severely ischaemic, the possible existence of two pathologic events namely inflammatory and thrombotic could have worsened the underlying ischemia and precipitated the occurrence of neovascular glaucoma in the right eye in 2 weeks. Secondary endotheliitis, which leads to mechanical vasoconstriction, cytokine storm which activates clotting factors, and stasis with hypoxia can stimulate pro-coagulation mechanisms.19 However identification of underlying thrombotic event could not be found in our case as also reported by Walinjkar et al.12 Also the patient had an uncomplicated stay at the hospital during the active COVID state with no documented signs of thrombosis or cytokine storm. It is possible that a more refined investigative panel would have identified some underlying prothrombotic state. A worsening clinical picture probably warrants a more elaborate quest for proof of such mechanisms and titrate management.

Conclusion

Considering the ensuing COVID-19 pandemic, patients with the retinal vascular or inflammatory disease may present with rapid onset neovascular glaucoma as a consequence of the primary retinal pathology. In addition to antiglaucoma medications, there is a role of pan-retinal photocoagulation and possibly anti-VEGF therapy in these eyes.

Clinical Significance

Ophthalmologists should be alert of patients presenting with rapid onset of NVG in the backdrop of COVID-19, and plan relevant investigations and institute early intervention.

Orcid

Jay U Sheth https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3590-7759

Unnikrishnan Nair https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0894-5124

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript None

References

- 1.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sen M, Honavar SG, Sharma N, et al. COVID-19 and eye: a review of ophthalmic manifestations of COVID-19. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:488–509. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_297_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shazly TA, Latina MA. Neovascular glaucoma: etiology, diagnosis and prognosis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2009;24(2):113–121. doi: 10.1080/08820530902800801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayreh SS. Neovascular glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007;26(5):470–485. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodrigues GB, Abe RY, Zangalli C, et al. Neovascular glaucoma: a review. Int J Retin Vitr. 2016;14(2):26. doi: 10.1186/s40942-016-0051-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senthil S, Dada T, Das T, et al. Neovascular glaucoma - a review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(3):525–534. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1591_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Deng C, Chen X, et al. Ocular manifestations and clinical characteristics of 535 cases of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a cross-sectional study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020;98(8):e951–e959. doi: 10.1111/aos.14472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Güemes-Villahoz N, Burgos-Blasco B, García-Feijoó J, et al. Conjunctivitis in COVID-19 patients: frequency and clinical presentation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(11):2501–2507. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04916-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tisdale AK, Chwalisz BK. Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of coronavirus disease 19. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2020;31(6):489–494. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawalha K, Adeodokun S, Kamoga GR. COVID-19 induced acute bilateral optic neuritis. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2020;8:2324709620976018. doi: 10.1177/2324709620976018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walinjkar JA, Makhija SC, Sharma HR, et al. Central retinal vein occlusion with COVID-19 infection as the presumptive etiology. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(11):2572–2574. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2575_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheth JU, Narayanan R, Goyal J, et al. Retinal vein occlusion in COVID-19: a novel entity. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(10):2291–2293. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2380_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaba WH, Ahmed D, Al Nuaimi RK, et al. Bilateral central retinal vein occlusion in a 40year old man with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e927691-1–e927691-5. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.927691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acharya S, Diamond M, Anwar S, et al. Unique case of central retinal artery occlusion secondary to COVID-19 disease. IDCases. 2020;21:e00867. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumitrascu OM, Volod O, Bose S, et al. Acute ophthalmic artery occlusion in a COVID-19 patient on apixaban. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(8):104982. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zapata MÁ, Banderas García S, Sánchez-Moltalvá A, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities in patients after COVID-19 depending on disease severity. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020:bjophthalmol-2020-317953. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker RC. COVID-19-associated vasculitis and vasculopathy. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. 2020;50(3):499–511. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02230-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Insausti-García A, Reche-Sainz JA, Ruiz-Arranz C, et al. Papillophlebitis in a COVID-19 patient: Inflammation and hypercoagulable state. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;32(1):NP168–NP172. doi: 10.1177/1120672120947591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]