Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to radical disruptions to the routines of individuals and families, but there are few psychometrically assessed measures for indexing behavioural responses associated with a modern pandemic. Given the likelihood of future pandemics, valid tools for assessing pandemic-related behavioral responses relevant to mental health are needed. This need may be especially salient for studies involving families, as they may experience higher levels of stress and maladjustment related to school and business closures. We therefore created the Pandemic Avoidance and Concern Scales (PACS) to assess caregivers’ and youths’ adjustment to COVID-19 and future pandemics. Concern and Avoidance factors derived from exploratory factor analyses were associated with measures of internalizing symptoms, as well as other indices of pandemic-related disruption. Findings suggest that the PACS is a valid tool for assessing pandemic-related beliefs and behaviors in adults and adolescents. Preliminary findings related to differential adjustment between caregivers and youths are discussed.

Keywords: Covid-19, Pandemic, Avoidance, Concern, Assessment, Adolescents, Families

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have a substantial global impact on individuals’ psychological well-being, leading to anxiety about financial hardship (Mann et al., 2020), health, increased loneliness (Tull et al., 2020), and general psychological distress (Findlay & Arim, 2020; Li et al., 2021) world-wide. While there are extant measures designed to assess reactions to major stressful life events (e.g., McCubbin et al., 1991; Horowitz et al., 1979) and relatively minor everyday hassles (e.g., Cohen, 1994), the COVID-19 pandemic may be associated with unusual behavioural responses that are not well captured by existing stress measures. For example, unlike other large-scale disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to community lockdowns, social distancing practices, and mandated business closures (Dubey et al., 2020). Despite recent advancements in vaccine technology, complete eradication of the COVID-19 virus may not be possible given widespread infection and genotypic variants (Jabbari & Rezaei, 2020), and future pandemics are likely to increase in both frequency and severity (Tabish, 2020) given recent trends (Castillo-Chavez et al., 2015), current globalization, and governmental policies (Frutos et al., 2020; Tabish, 2020). Thus, given the limited scope of extant stress measures and the strong potential for widespread viral outbreaks in the future, there is a need for measures designed to assess responses to the unique sequalae of pandemics.

Ideally, such measures can assess pandemic-related behavioural responses across a range of ages. While adults are experiencing the aforementioned novel stressors in the context of the pandemic, the social isolation caused by school closures and community lockdowns may be especially detrimental to youths’ short- and long-term mental health (Ellis et al., 2020; Fegert et al., 2020; Magson et al., 2021). School and work closures stemming from the pandemic have also led to increased parenting stress (Brown et al., 2020; Hiraoka & Tomoda, 2020; Spinelli et al., 2020), potentially impairing caregiving which could lead to further youth impairment (Spinelli et al., 2020). Given adolescents’ potentially heightened sensitivity to social isolation (Ellis et al., 2020) and the potential for increased stress within locked-down families (Lee et al., 2020), measures that assess the behavioural impact of pandemics on family members who vary in age and developmental stage are needed.

Several groups developed pandemic impact measures early in the pandemic, including the Epidemic–Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII; Grasso et al., 2020) and the COVID Stress Scales (Taylor et al., 2020). However, many of these measures were developed for adults and have not been extensively vetted from a psychometric standpoint (i.e., rationally derived, lacking an investigation of factor structure which identifies underlying constructs). Additionally, given that repeated assessment may be needed to capture the dynamic nature of pandemics’ impact, these measures may be impractical (e.g., the EPII is over 90 items and therefore may be difficult to integrate into brief assessment batteries). While other measures are brief and developed for use with emerging adults (e.g., Kujawa et al., 2020), these have not been validated for use with both adults and adolescents, and often contain items tapping content less relevant to younger individuals (e.g., younger children may be less aware of financial strain).

The Current Study

The current study describes the development the Pandemic Avoidance and Concern Scales (PACS), a relatively brief measure of behavioral and emotional responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as a preliminary assessment of its psychometric properties. While this measure was developed specifically in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, items were designed to assess stress related to any large-scale disease outbreak, and to be developmentally appropriate for a broad age range, including adolescents and adults. With respect to study hypotheses, we predicted that youths’ and parents’ scores on the PACS would be positively correlated, given that the pandemic was likely to have a somewhat similar impact on members of the same family. We also predicted that the factor structure of the PACS would be similar for adults and adolescents, although this hypothesis was more tentative given the lack of relevant prior research. Finally, given established associations between life stress and internalizing symptoms (Harkness & Monroe, 2016), and given that the PACS was designed to capture disruption and behavioral changes stemming from the pandemic, we predicted that the PACS would be moderately associated with depressive and anxious symptoms in both caregivers and adolescents.

Methods

Participants

Participants were caregiver-youth dyads drawn from an ongoing longitudinal study of children’s emotional development (N = 409) that began when children were three-year-olds; families have been followed up multiple times over the past 13 years (e.g., Daoust et al., 2018). Families were originally recruited from the community using a combination of local and digital advertisements, as well as contacting individuals in the Western University participant pool. Children with serious mental or physical problems, as assessed by parent report in an initial screening interview, were ineligible to participate. A proxy measure of children’s cognitive ability (i.e., the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Fourth Edition; Dunn & Dunn 2007), administered when children were 3 years old, showed that participating children were, on average, in the normal range of cognitive ability (M = 113.31, SD = 14.81). Families were representative of the Ontario community from which they were recruited (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Of the original 409 families involved in the study, 301 parent-child dyads (73.6%) participated in the current study focused on family adjustment in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We initiated the first wave of data collection for the current study in March 2020, contemporaneously with local implementation of COVID-19 related public health measures. Participants were recruited on an ongoing basis throughout data collection unless they requested not to be contacted. The current study included twelve waves of data collection, with each wave spaced approximately two weeks apart. Fourteen families (3%) from the original sample dropped out of the larger study prior to the current study, 35 families (9% of the original sample) declined to participate in the current study, and 59 (14% of the original sample) did not respond to invitations to participate.

Wave 6 of data collection, collected in mid-June 2020, was used for scale development as it had the largest cross-sectional sample; 234 primary caregivers (224 mothers; Mage = 44.92 years, SD = 4.79) and 223 children (124 girls; Mage = 14.34 years, SD = 1.17) completed surveys at this time point, yielding data from 236 families (i.e., 57.7% of the original sample of 409 families provided data for current study analyses). For an 11-year-long follow-up study, this retention rate is better than expected (Teague et al., 2018). Chi-square and t-tests were used to compare the current subsample to members of original sample who did not participate in this follow-up study; the groups did not significantly different when compared on caregiver or youth age, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, maternal lifetime history of anxious or depressive disorders (assessed via clinical interview; see Vandermeer et al., 2020, for more details), or youths’ depressive or anxious symptoms at age 11 (i.e., the most proximal previous assessment wave available; all ps > 0.05). Data were collected using Qualtrics XM (Qualtrics, USA), with separate individual survey links sent by email to parents and youths to allow for independent self-report.

Measures

During each wave of data collection, potential PACS items (i.e., those covering pandemic-related concerns and behaviours) were administered first, followed by items assessing pandemic-related stressful events and relevant internalizing symptom measures.

Pandemic-Related Concerns and Behaviours

We initially created a pool of 18 items to assess adolescents’ and caregivers’ responses to the pandemic, 17 of which were ultimately used in the PACS1. Items were developed based on theoretical considerations (e.g., individuals may vary in their level of concern about infection), expert opinion, review of item content from existing scales (i.e., EPII; Grasso et al., 2020; Pandemic Stress Questionnaire; Kujawa et al., 2020) and findings from other recent studies that did not focus explicitly on measure development (i.e., Hawes et al., 2021). Items inquired about pandemic-related concerns (e.g., perceived likelihood of becoming infected with COVID-19) and behaviors (e.g., sanitizing surfaces because of COVID-19), as well as general mental well-being. These items were administered at every wave of data collection (i.e., at Waves 1 through 12), which occurred once every two weeks.

To examine relations between pandemic-related concerns and behavioural change, 25 items covering more stable phenomena (e.g., occupational status/activities, requirements to shelter in place, COVID status of family/friends) were administered once per month (i.e., at Waves 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 of data collection) to examine associations between the PACS and life events related to the pandemic. All monthly items were completed by the primary caregiver and a subset were also completed by participating youths in cases in which youths were likely to be knowledgeable regarding the item in question (e.g., items related to their own thoughts and behaviour). As these items are causal indicators (i.e., indicators that instantiate or give rise to experiences of life stress) rather than reflective of an underlying construct (Ellwart & Konradt, 2011), we did not expect the life events data to possess a higher-order factor structure. As such, these were excluded from analyses of factor structure and internal consistency.

A full list of questionnaire items used in the present study can be found in Table 1. After accounting for the influence of pandemic-related language (i.e., use of the phrases “COVID-19” and “pandemic”, an understanding of which was a prerequisite for participation in our study), post-hoc analyses of readability (Flesch Reading Ease, 73.8; Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, 6.5) suggested that our measure should be easily comprehended by both adults and adolescent-aged youth.

Table 1.

Pandemic Avoidance and Concern Scales (PACS) Questionnaire Items

| Item Designation | Item Text | Response Options |

|---|---|---|

| Biweekly Items | ||

| Q1 | How concerned have you been about the coronavirus (COVID-19) during the past two weeks? |

0 - Not at all 1 - A little bit 2 - Moderately 3 - Quite a bit 4 - Extremely |

| Q2 | How likely do you think it is that you could become infected with the coronavirus (COVID-19)? | |

| Q3 | During the past two weeks, which of the following behaviours have you engaged in due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic? (check all that apply) |

0 - No 1 – Yes |

| Q3.1 | Purchased hygiene products (e.g., Purell, disinfectant spray/wipes, hand soap) | |

| Q3.2 | Purchased extra food and/or beverages | |

| Q3.3 | Purchased extra health and/or beauty aid products (e.g., toilet paper, toothpaste) | |

| Q3.4 | Checked your body for signs of illness (e.g., taken temperature) | |

| Q3.5 | Called a helpline or accessed health materials on the internet for information | |

| Q4 | During the past two weeks, how often have you done the following things due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic? |

0 – Never 1 - Several times a week 2 - Once a day/daily 3 - Several times a day 4 - Many times a day |

| Q4.1 | Checked the news (newspaper, online, phone, TV) for updates on COVID-19 | |

| Q4.2 | Used a hygienic product (e.g., Purell/hand sanitizer, disinfectant spray/wipes, washed hands for much longer than usual with soap) as a precaution for COVID-19 | |

| Q4.3 | Cleaned surfaces (e.g., doorknobs, keyboards, cell phones) as a precaution for COVID-19 | |

| Q5 | During the past two weeks, how often did you purposely avoid the following activities because of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic? |

0 - Never or Not Applicable 1 - Once or twice 2 - Three or four times 3 - Every day |

| Q5.1 | Avoided going to work or school | |

| Q5.2 | Avoided public places (e.g., grocery store, restaurants, shops, gym) | |

| Q5.3 | Avoided social activities (e.g., visiting friends, clubs, extracurricular activities | |

| Q5.4 | Avoided going on a date with a friend or partner | |

| Q5.5 | Avoided public transportation (e.g., airplane, train, bus, subway) | |

| Q5.6 | Avoided touching my face | |

| Q5.7 | Avoided touching another person (e.g., shaking hands, hugging, kissing) | |

| Q5.8 | Avoided going to the doctor or hospital | |

| Q5.9 | If you avoided any of the activities listed above, why (check all that apply)? |

0 - No 1 – Yes |

| Q5.9.1 | I was concerned about being infected | |

| Q5.9.2 | I was concerned about infecting other people | |

| Monthly Items | ||

| MQ1 a | Think about your life circumstances prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, or what your life is usually like. Compared to your typical life, to what extent has the COVID-19 pandemic changed your life circumstances during the past month? Consider both positive and negative changes in making your rating. |

0 - Not at all; the COVID-19 pandemic has not impacted my life in the last month 1 - A little; the COVID-19 pandemic had a small impact on my life this past month 2 - Moderate; the COVID 19 pandemic has moderately changed my life this past month 3 - Quite a bit; the COVID-19 pandemic has had a strong impact on my life this past month 4- Extreme; the COVID-19 pandemic has had an extremely strong impact on my life this past month |

| MQ2 a | Again, think about your life circumstances prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, or what your life is usually like. Generally speaking, how do you feel about these changes that COVID-19 has brought to your life during the past month? |

-4 - Extremely negative; all the changes to my life due to COVID-19 are extremely undesirable -3 - Very negative -2 - Moderately negative -1 - A little bit negative 0 - Neutral; either no changes occurred due to COVID-19 this past month or the changes were a mix of welcome and unwelcome changes 1 - A little bit positive 2 - Moderately positive 3- Very much Positive 4 - Extremely positive; all the changes to my life due to COVID-19 are extremely welcome or positive |

| MQ3 a | During the past month, have you or others living in your home been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in any of the following ways? When relevant, you can indicate that something happened to both yourself and someone else in the home by selecting BOTH ‘a’ and ‘b’ |

0 - No / Not applicable 1 - Yes |

| MQ3.1 a | Your child(ren)’s school/classes moved to online instruction. | |

| MQ3.2 a | Change of residence | |

| MQ3.3 a b | Shelter in place (avoiding leaving the house, except to be outdoors) |

0 – No / Not applicable 1 – Yes, this happened to another person/people in my home 2 – Yes, this happened to me 3 – Yes, this happened to me AND another person/people in my home |

| MQ3.4 a b | Self-quarantine (completely avoiding contact with other people) | |

| MQ3.5 a b | Job/occupation/work moved to at home/remote/online | |

| MQ3.6 a b | Reduced hours or laid off from work | |

| MQ4.1 a b | Had to work even though in close contact with people who might be infected (e.g., customers, patients, co-workers). | |

| MQ4.2 a b | Hard time doing job well because of needing to take care of people in the home. | |

| MQ4.3 a b | Job entailed providing care of any kind to people with COVID-19 (e.g., physician, nurse, support staff, custodial). | |

| MQ4.4 a b | Had to take over teaching or instructing a child (or children) at home due to COVID-19. | |

| MQ4.5 a b | Did not have the ability or resources to talk to family or friends while separated. | |

| MQ4.6 a b | Unable to access medical care for a serious condition (e.g., dialysis, chemotherapy). | |

| MQ5 a | In the past month, have you been tested for coronavirus (COVID-19)? |

0 - No 1 - Yes |

| MQ5.1 a | If yes, what was the result of the test? |

0 - Negative 1 - Do not know 2 - Positive |

| MQ6 a | In the past month, has your child (the one in our study) been tested for coronavirus (COVID-19)? |

0 - No 1 - Yes |

| MQ6.1 a | If yes, what was the result of the test? |

0 - Negative 1 - Do not know 2 - Positive |

| MQ7 a | In the past month, do you know anyone who has tested positive for coronavirus (COVID-19)? |

0 - No 1 - Yes |

| MQ7.1 a b | If yes, who (check all that apply)? | 1 point each – Family member, romantic partner, friend, roommate, co-worker, other (please specify) |

| MQ8 a | In the past month, have you or has anyone close to you been hospitalized due to coronavirus (COVID-19)? |

0 - No 1 - Yes |

| MQ8.1 a b | If yes, who (check all that apply)? | 1 point each – Family member, romantic partner, friend, roommate, co-worker, other (please specify) |

| MQ9 a | In the past month, has anyone close to you died due to coronavirus (COVID-19)? |

0 - No 1 - Yes |

| MQ9.1 a b | If yes, who (check all that apply)? | 1 point each – Family member, romantic partner, friend, roommate, co-worker, other (please specify) |

| MQ10 a c | What is your current occupational status (check all that apply)? |

1 - Temporarily unemployed due to COVID or Laid-off/fired due to COVID. 0 - Other (i.e., current student (college), current student (high school), full-time employed and going to work, full-time employed and working from home, work part-time and going to work, work part-time and working from home, unemployed prior to coronavirus outbreak) |

| MQ11 | Over the past month, how much privacy do you have? |

2 – Much more privacy than I want / Much less privacy than I want 1 – A little more privacy than I want / A little less privacy than I want 0 – Just as much privacy as I want |

| MQ12 c | During the past week, approximately how many people each day did you interact with in person (i.e., not through use of technology)? If you did not interact with anyone in person, enter 0. |

0–0–2 individuals 1–3–4 individuals 2–5–7 individuals 3–8–10 individuals 4–11 + individuals |

| MQ13 c | During the past week, approximately how many people each day did you interact with via technology (e.g., call, text, FaceTime, Skype)? If you did not interact with anyone via technology, enter 0. Do NOT include people you also saw in person. For example, if you texted your child while also seeing them at home, do not include them in your count. | |

| MQ14 | During the past month, has the coronavirus affected how emotionally close you and others living in your home feel toward one another? |

2 - We feel much closer to each other 1 - We feel somewhat closer to each other 0 - No change - we are as close as before -1 - We feel somewhat less close to each other -2 - We feel much less close to each other |

| MQ15 | During the past month, has the coronavirus affected the degree to which there is conflict among people living in your home? |

2 - There is much less conflict/problems 1 - There is somewhat less conflict/problems 0 - There has been no change in the degree of conflict or problems -1 - There is somewhat more conflict/problems -2 - There is much more conflict/problems |

| MQ16 a | During the past month, do you have enough food or basic household items (e.g., soap, toilet paper)? |

2 – Yes 1 – We have enough of some things but are lacking others 0 - No |

| MQ17 a | During the past month, have you experienced or are you expecting a substantial reduction in personal or family income? |

3 – No change or an increase 2 – Don’t know 1 – Yes, some reduction 0 – Yes, substantial reduction |

| MQ17.1 a | If you chose a or b (i.e., you expect a reduction in income), how will this affect you, now or in the future? |

4 – Not at all 3 – Slight effect 2 – Moderate effect 1 – Strong effect 0 – Extremely strong effect |

Note: “COVID-19” and “coronavirus” can be swapped to a proximal disease event if needed in future studies. All items were translated to z-scores before entry into EFAs. a indicates questions were asked to caregivers only. b indicates items recoded as scores summed across multiple checked items. c indicates items recoded as categorical variables

Caregivers’ and Youths’ Internalizing Symptoms

Given the large literature showing associations between stressful life events and anxiety and depression (Haig-Ferguson et al., 2021; Harkness & Hayden, 2020), we examined associations between pandemic-related behaviour and caregiver and youth symptom measures completed by the relevant respondent at the selected wave of data collection to assess our measure’s predictive validity for emotional adjustment in the context of pandemic-related disruption.

General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

Caregivers completed the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006), a brief 7-item self-report measure for indexing symptoms of anxiety in adults. Developed based on criteria for generalized anxiety disorder from the DSM-IV-TR, items include “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge” and “worrying too much about different things.” Participants respond to items on a scale of 0 to 3, reflecting “not at all” to “nearly every day” based on their experiences over the past 2 weeks. Responses are summed into a single overall score; scores of 5, 10, and 15 are recommended as benchmarks of mild, moderate, and severe anxiety respectively. The GAD-7 showed excellent internal consistency (N = 223, α = 0.90) in our sample.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Caregivers also completed the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001), a brief self-report measure for indexing symptoms of depression in adults. The PHQ-9 has items representing each of the 9 diagnostic criteria for depression in the DSM-IV; items include “little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.” Respondents rate items on a scale of 0 to 3, reflecting “not at all” to “nearly every day” based on their experiences over the past two weeks. Responses are summed into a single overall score; scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 are recommended as benchmarks of mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively. 70.4% of caregivers reported minimal symptoms, 19.3% reported mild symptoms, 6% reported moderate symptoms, 1.7% reported moderately severe symptoms, and 2.6% reported severe symptoms. The PHQ-9 showed excellent internal consistency (N = 223, α = 0.90) in our sample.

Youth Self Report (YSR)

The YSR (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used to assess participating adolescents’ emotional and behavioral problems. The YSR is a 105-item self-report measure designed for ages 11 to 18 which describe behaviors related to internalizing and externalizing disorders. Adolescents rated themselves on each item on a scale of 0 (“not true”), 1 (“sometimes true”), or 2 (“very true”) based on their experience of the past two weeks; individual items were summed into relevant subscale scores. In in order to limit participant burden, only the anxious/depressed (12 items, α = 0.90), withdrawn/depressed (8 items; α = 0.84), and somatic complaints (10 items; α = 0.80) subscales were administered. The somatic complaints subscale was included given a posited increase in health-related anxiety in youth facing pandemics (Haig-Ferguson et al., 2021).

Data Analytic Approach

Exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) were conducted using MPlus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) to determine the factor structure of pandemic-related behaviors and beliefs (i.e., Q1 through Q5.8). Given that individual items had different response formats (e.g., not at all to extremely for some items, never to many times per day for others), all items were transformed into standardized z-scores prior to conducting EFAs. A maximum likelihood estimator was used in all models and an oblique geomin rotation was applied given that emergent factors were expected to be correlated.

To examine the construct validity of the aforementioned items designed to tap pandemic-relevant behaviour, we used bivariate correlations to characterize associations between scales tapping these behaviours and internalizing symptoms and life events impacting the family. Factor analyses were not conducted on items covering stressful life events, which are formative constructs, rather than indicators of a latent construct (Ellwart & Kondrat; 2011). More specifically, these theoretically independent events contribute towards family stress rather than reflecting it as a latent construct. Instead, these were summed to create scale scores of “routine disruption,” “income instability,” and “COVID exposure” (for a description of these aggregate variables, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Monthly questionnaire items and descriptive statistics

| Item Designation | Item Text | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Routine Disruption | ||||

| MQ3.1 | Child’s school moved to online instruction | 0.990 | 0.093 | 0–3 |

| MQ3.2 | Change of residence | 0.020 | 0.145 | 0–3 |

| MQ3.3 | Shelter in place | 1.517 | 1.223 | 0–3 |

| MQ3.4 | Self-quarantine | 0.551 | 1.031 | 0–3 |

| MQ4.4 | Had to take over teaching or instructing a child at home | 1.681 | 0.973 | 0–3 |

| MQ4.5 | Wasn’t able to see friends | 0.055 | 0.314 | 0–3 |

| MQ11 a | Dissatisfaction with privacy | 1.360 | 0.482 | 0–2 |

| Income Instability | ||||

| MQ3.5 b | Job/occupation/work moved to at home/remote/online | 1.440 | 1.083 | 0–3 |

| MQ3.6 | Reduced hours or laid off from work | 0.852 | 1.011 | 0–3 |

| MQ4.2 | Difficult to do job because of changes at home | 0.964 | 1.095 | 0–3 |

| MQ10 | Job loss on account of pandemic | 0.164 | 0.371 | 0–1 |

| MQ16 b | Enough food/resources | 0.030 | 0.243 | 0–2 |

| MQ17 | Substantial change in income | 0.860 | 1.123 | 0–3 |

| MQ17.1c | Impact of income reduction | 0.350 | 0.775 | 0–4 |

| COVID Exposure | ||||

| MQ4.1 | Had to work in contact with people who might have pandemic disease | 0.787 | 0.989 | 0–3 |

| MQ4.3 | Job entails caretaking for people with pandemic disease | 0.133 | 0.476 | 0–3 |

| MQ5 | Was tested for pandemic disease | 0.030 | 0.182 | 0–1 |

| MQ5.1c | Results of pandemic disease test | 0.010 | 0.085 | 0–2 |

| MQ6 | Child was tested for pandemic disease | 0 | 0 | 0–1 |

| MQ6.1c | Result of child’s pandemic disease test | 0 | 0 | 0–2 |

| MQ7 | Know someone who tested positive for pandemic disease | 0.180 | 0.385 | 0–1 |

| MQ8 | Know someone who was hospitalized for pandemic disease | 0.030 | 0.171 | 0–1 |

| MQ9 | Know someone who had died from pandemic disease | 0.010 | 0.092 | 0–1 |

| MQ12 | How many people interacted with in-person | 1.917 | 1.363 | 0–4 |

Note: All items were translated to z-scores before summed into aggregate items. a indicates items recoded to reflect overall dissatisfaction, b indicates reverse-coded items, c indicates items that were offered to participants only if they had endorsed a previous relevant item and were scored as 0 if not offered

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for participating caregivers and youths are in Table 3. Participating families were primarily Caucasian (92.4%, African-Canadian = 0.4%, Asian = 2.1%, Hispanic = 2.5%, Other = 2.5%) and largely middle- to upper-class in socioeconomic status (SES; 3.1% < $20,000, 10.2% = $20,000-$40,000, 26.1% = $40,001-$70,000, 29.6% = $70,001-$100,000, 31.0% > $100,000; annual household income in Canadian Dollars).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable | Mean | (SD) | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth Age | 14.72 | (0.41) | 13.92–15.68 | 0.25 | − 0.80 |

| Caregiver’s Age | 44.76 | (4.83) | 32.35–61.11 | 0.14 | 0.52 |

| PPVT (Baseline) a | 113.31 | (14.81) | 59–147 | − 0.38 | 0.31 |

| Family Income b | 3.75 | (1.10) | 0–4 | 0.54 | − 0.48 |

| YSR Anxious/Depressed c | 5.06 | (5.13) | 0–22 | 1.14 | 0.72 |

| YSR Withdrawn/Depressed c | 3.35 | (3.27) | 0–16 | 1.35 | 1.99 |

| YSR Somatic Complaints c | 2.54 | (3.00) | 0–13 | 1.34 | 1.18 |

| Caregiver GAD-7 d | 3.77 | (4.03) | 0–21 | 1.77 | 3.66 |

| Caregiver PHQ-9 e | 3.91 | (4.70) | 0–23 | 1.97 | 4.15 |

a Standard Score on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Fourth Edition (Dunn & Dunn, 2007)

b 1 = < $20,000, 2 = $20,000-$40,000, 3 = $40,001-$70,000, 4 = $70,001-$100,000, 5 = > $100,000; all in Canadian dollars

c Subscale Score on the Youth Self Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001)

d Total Score on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006)

e Total Score on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001)

In terms of symptoms reported on the YSR (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), 85.1% of youths reported subclinical anxious-depressed symptoms, while 7.2% reported elevated symptoms, and 7.1% reported clinical levels of symptoms. Similarly, 88.7% of youths reported subclinical withdrawn-depressed symptoms, while 5% reported elevated symptoms, and 6.3% reported clinical levels of symptoms. 90.6% of youths reported subclinical somatic complaints, while 8.1% reported elevated complaints, and 1.3% reported clinical levels of complaints. Means fell below clinical thresholds for the all subscales and means from the anxious-depressed and withdrawn-depressed scales were consistent with prior work involving non-referred normative samples (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The sample mean of somatic complaints scores was elevated but sub-clinical compared to a reference sample (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), likely due to normative increases in health-related concern in the context of the pandemic.

On the GAD-7, 70% of caregivers reported minimal anxious symptoms, 21.5% reported mild symptoms, 5.6% reported moderate symptoms, and 3% reported severe symptoms. On the PHQ-9, 70.4% of caregivers reported minimal depressive symptoms, 19.3% reported mild symptoms, 6% reported moderate symptoms, 1.7% reported moderately severe symptoms, and 2.6% reported severe symptoms. Rates of moderate-to-severe anxious or depressive symptoms in our sample were somewhat lower than those of parents in a comparable, large-scale study (Sequeira et al., 2021); this may be accounted for by the relatively higher socioeconomic status of our sample.

Descriptive statistics for caregivers’ and youths’ item-level responses are available in Appendices A and B. The majority of PACS items were significantly correlated with one another, notably within items tapping concern (i.e., Q1 through Q4.3; Mcorrelation = 0.23, Rangecorrelation = − 0.03 − 0.53) and within items tapping avoidance (i.e., Q5.1 through Q5.8; Mcorrelation = 0.31, Rangecorrelation =.-0.01 − 0.60). Item 3.5 (i.e., called a COVID helpline or accessed health materials on the internet) was minimally correlated with other PACS items in both the caregiver and youth data.

Factor Structure of Pandemic-Related Behaviours

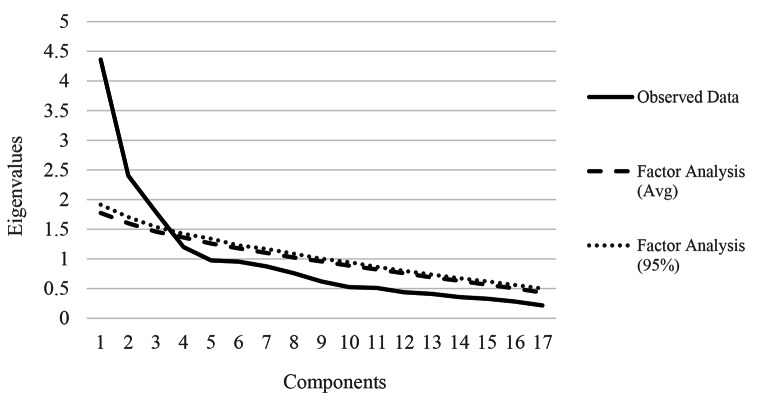

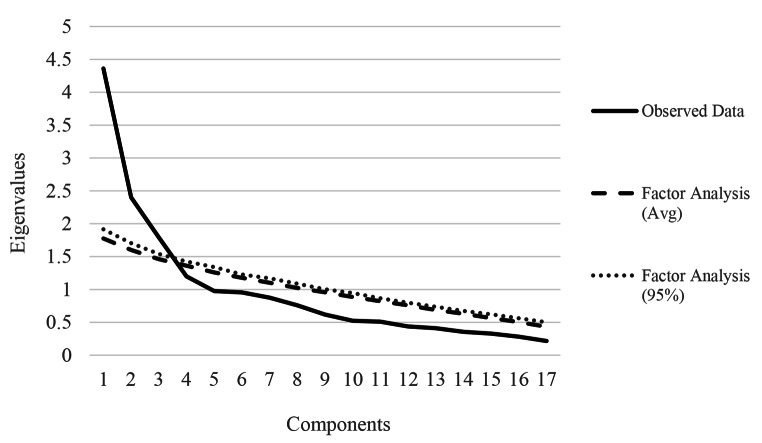

As noted in study hypotheses, we had no reason to anticipate differences between youths and adults in our measure’s factor structure. To examine the similarity of the factor structure of pandemic-related behaviors and beliefs between caregivers and adolescents, parallel analyses (Horn, 1965) were used on the EFA-derived factors in each group with principal components using 100 replications of simulated data in each group to inform the number of factors to extract in each dataset (i.e., caregiver and youth); parallel analysis indicated that a maximum of three potential factors could be extracted in the parent data (Fig. 1) and two in the youths’ data (Fig. 2). The third potential factor in the parents’ data consisted of only three items reflecting purchases during the pandemic, which we felt was not a clearly interpretable construct; thus, we focused on the more parsimonious and interpretable two-factor solutions in data from youths and caregivers.

Fig. 1.

Results of parallel analysis of caregivers’ Pandemic Avoidance and Concern Scales (PACS)

Fig. 2.

Results of parallel analysis of youths’ Pandemic Avoidance and Concern Scales (PACS)

The results of the EFA suggested that an overall two-factor model of: (1) Pandemic Concern (Q1 through Q4.3 and Q5.6) and (2) Pandemic Avoidance (Q5.1 through Q5.5, Q5.7, and Q5.8) best reflected the structure of parent and youth data, leading us to call this measure the Pandemic Avoidance and Concern Scales (PACS). Item Q3.5 was excluded from conducted EFAs as it was not associated with any factor in the parent data and had no variance in youth data. The inter-factor correlation was 0.30 and 0.26 in the parent and youth data, respectively.

See Table 4 for the identified two-factor structure of the biweekly questionnaire data for both parents and youth. In both caregivers and youths, items assessing anxious anticipation of pandemic-related dangers loaded moderately to strongly onto Factor 1 (Concern; Mloading = 0.47; Rangeloadings = 0.15 − 0.86), while items assessing avoidance of physical locations and social activities that may increase the risk for catching COVID loaded moderately to strongly onto Factor 2 (Avoidance; Mloading = 0.63; Rangeloadings = 0.27 − 0.86). In the parent data, item Q3.4 (i.e., checked self for symptoms) did not load significantly on either factor, while item Q5.6 (i.e., avoided touching face) loaded significantly on both factors, albeit more strongly on the Concern factor. In the youth data, items Q2 (i.e., perceived chance of infection) and Q3.2 (i.e., purchased extra food/drink) did not load significantly on either factor. Despite these suboptimal loadings, items which loaded onto a factor in at least one subsample were retained and attributed to the factor with which they loaded most strongly in order to allow for a unified measure between caregivers and youths. Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega for Caregiver Concern (9 items; α = 0.73, ω = 0.7), Caregiver Avoidance (8 items; α = 0.79, ω = 0.80), and Youth Avoidance (8 items; α = 0.82, ω = 0.83) indicated acceptable internal consistency for the item sets identified as reflecting each resulting factor, but the Cronbach’s alpha for Youth Concern (9 items; α = 0.69, ω = 0.71) fell slightly short of traditional cut-offs for acceptable internal consistency. The identified factor structures for parent and youth data appeared consistent, with 14 of 17 items having significant primary loadings on the same factor (e.g., Q1 assessing disease-related concern loaded moderately strongly onto the Concern factor and very weakly onto the Avoidance factor in both the parent and youth data). We formally evaluated the similarity of factor loadings in youths and caregivers using Tucker’s congruence coefficients, in which coefficients ≥ 0.90 indicate strong similarity in factor loadings (Lorenzo-Seva & ten Berge, 2006). These analyses indicated that factors loadings were very similar across caregiver and youth subsamples for both the Concern (r = .93) and Avoidance (r = .96) factors.

Table 4.

Exploratory Factor Analysis Results for Pandemic Avoidance and Concern Scales (PACS) Questionnaire Items

| Biweekly Questionnaire Items | Parent Data | Youth Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor A Loadings “PACS Concern” |

Factor B Loadings “PACS Avoidance” |

Factor A Loadings “PACS Concern” |

Factor B Loadings “PACS Avoidance” |

||

| Q1 | Disease-related concern C | 0.508 | 0.055 | 0.461 | 0.028 |

| Q2 | Perceived chance of infected C | 0.320 | 0.081 | 0.169 | − 0.054 |

| Q3.1 | Purchased hygiene products C | 0.672 | − 0.052 | 0.657 | 0.070 |

| Q3.2 | Purchased extra food/drink C | 0.417 | 0.177 | 0.207 | 0.200 |

| Q3.3 | Purchased extra health products C | 0.375 | 0.176 | 0.406 | − 0.014 |

| Q3.4 | Checked self for symptoms C | 0.151 | 0.042 | 0.390 | 0.115 |

| Q4.1 | Frequency of checking news C | 0.446 | 0.044 | 0.572 | 0.003 |

| Q4.2 | Frequency of hygiene product use C | 0.742 | − 0.120 | 0.695 | 0.022 |

| Q4.3 | Frequency of cleaning surfaces C | 0.623 | 0.002 | 0.864 | − 0.202 |

| Q5.1 | Avoided work/school A | − 0.106 | 0.266 | 0.195 | 0.428 |

| Q5.2 | Avoided public places A | 0.023 | 0.691 | 0.090 | 0.652 |

| Q5.3 | Avoided social activities A | − 0.027 | 0.782 | 0.049 | 0.812 |

| Q5.4 | Avoided dates A | − 0.143 | 0.783 | − 0.095 | 0.855 |

| Q5.5 | Avoided public transit A | 0.081 | 0.634 | − 0.179 | 0.802 |

| Q5.6 | Avoided touching face C | 0.427 | 0.241 | 0.446 | − 0.028 |

| Q5.7 | Avoided touching others A | 0.293 | 0.414 | 0.147 | 0.447 |

| Q5.8 | Avoided doctor/hospital A | 0.043 | 0.592 | 0.006 | 0.607 |

Note: Bolded items are significant at the 0.05 level

Items marked with C were used to calculate the Concern variable, while items marked with A were used to calculate the Avoidance variable

Correlations Between the PACS and Other Study Variables

See Table 5 for correlations between major study variables. Concern and Avoidance scores were unrelated to demographic variables, with the exception of girls reporting greater concern than boys. Notably, caregiver Concern and Avoidance were positively, weakly-to-moderately correlated with both caregiver anxiety and depression symptom measures, but not youth symptoms. Youth Concern was significantly, weakly positively related to all youth symptom scales, while youth Avoidance was not. The number of individuals that caregivers contacted in person or over technology was not significantly related to their own reports of Concern or Avoidance, but the number of people caregivers contacted in person was positively correlated with youths’ reported Concern. Parents’ Concern was negatively correlated with the number of individuals youths saw in person, and positively correlated with the number of individuals youths contacted via technology; youths’ own Concern was only correlated with the number of people they contacted via technology. Inter-item correlations for the PACS (i.e., item-level responses at Wave 6) are in Appendices A and B respectively; patterns of correlations indicate significant relationships within groups of items contributing to the Concern and Avoidance factors. Correlations between responses to the PACS at the two largest waves of data collection are in Appendix C; patterns of correlations indicate significant relationships for item-level responses and scale scores between Waves 6 and 7 of the study (i.e., a two-week gap between administrations).

Table 5.

Correlations between Pandemic Avoidance and Concern Scales (PACS) subscales and other study variables of interest

| Study Variables | Caregiver Data | Youth Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PACS Concern | PACS Avoidance | PACS Concern | PACS Avoidance | |

| Youth’s Age | 0.019 | 0.009 | − 0.022 | 0.010 |

| Youth’s Sex a | 0.016 | 0.023 | 0.215 ** | − 0.005 |

| Youth’s PPVT Score b | − 0.097 | 0.033 | 0.051 | 0.011 |

| Caregiver’s Age | 0.055 | 0.040 | 0.036 | − 0.004 |

| Caregiver’s Relationship to Youth c | 0.120 | 0.058 | 0.027 | 0.127 |

| Ethnicity d | 0.041 | 0.026 | 0.042 | 0.021 |

| Family Income e | − 0.053 | 0.027 | 0.092 | 0.004 |

| Caregiver PACS Concern | - | 0.298 ** | 0.324 ** | 0.140 * |

| Caregiver PACS Avoidance | 0.298 ** | - | 0.123 | 0.365 ** |

| Youth PACS Concern | 0.324 ** | 0.123 | - | 0.260 ** |

| Youth PACS Avoidance | 0.140 * | 0.365 ** | 0.260 ** | - |

| Caregiver Routine Disruption (Aggregate) | 0.182 ** | 0.092 | 0.04 | − 0.028 |

| Caregiver Income Instability (Aggregate) | 0.111 | 0.030 | 0.152 * | 0.009 |

| Caregiver COVID Exposure (Aggregate) | 0.119 | 0.154 * | 0.100 | 0.007 |

| Caregiver # of People Seen In-Person | 0.120 | − 0.020 | 0.144 * | 0.012 |

| Caregiver # of People Contacted via Technology | 0.066 | 0.087 | 0.011 | 0.035 |

| Caregiver Closeness with Family | − 0.087 | 0.082 | 0.018 | 0.037 |

| Caregiver Conflict with Family | 0.035 | 0.164 * | 0.028 | 0.055 |

| Caregiver Anxiety (GAD-7) f | 0.389 ** | 0.198 ** | 0.118 | 0.102 |

| Caregiver Depression (PHQ-9) g | 0.236 ** | 0.175 ** | 0.061 | 0.083 |

| Youth # of People Seen In-Person | − 0.198 ** | − 0.046 | − 0.070 | − 0.029 |

| Youth # of People Contacted via Technology | 0.143 * | − 0.066 | 0.168 * | < 0.001 |

| Youth Closeness with Family | − 0.093 | 0.034 | 0.130 | 0.077 |

| Youth Conflict with Family | 0.124 | − 0.042 | 0.019 | − 0.012 |

| Youth Anxious/Depressed (YSR) h | 0.101 | 0.032 | 0.261 ** | 0.078 |

| Youth Withdrawn/Depressed (YSR) h | 0.098 | − 0.032 | 0.172 * | − 0.013 |

| Youth Somatic Complaints (YSR) h | 0.095 | 0.04 | 0.150 * | 0.029 |

Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01

a male = 0, female = 1

b Standard Score on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Fourth Edition (Dunn & Dunn, 2007)

c mother = 0, father = 1

d white = 0, other = 1

e 1 = < $20,000, 2 = $20,000-$40,000, 3 = $40,001-$70,000, 4 = $70,001-$100,000, 5 = > $100,000; all in Canadian dollars.

f Total Score on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006)

g Total Score on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001)

h Subscale Score on the Youth Self Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001)

Discussion

We developed and examined the psychometric properties of a measure of parents’ and youths’ behaviour during the COVID pandemic. Although pandemics appear to be increasing in frequency, a trend that will likely continue, there are few extant measures designed to assess behaviour specifically in response to the unique context of a pandemic; those that do exist have received limited psychometric scrutiny, been developed for either youth or adults (e.g., Kujawa et al., 2020), and may be unsuitable for examining behaviour over time, given their length (e.g., Grasso et al., 2020). Thus, measures of pandemic-related behaviour with formally evaluated factor structures are needed to guide assessment efforts when administering caregiver and youth measures. Our results suggest that a two-factor structure of concern and avoidance behaviors related to COVID yields scales with good psychometric properties in both youths and adults and shows that these factors are related to extant measures of parent and youth symptoms in a meaningful way.

As hypothesized, parent and offspring PACS scores were moderately correlated, indicting similarity in parent-child dyads in terms of experiences and behavioral changes related to the pandemic. Relatedly, the factor structure of the PACS was similar in adults and adolescents. We intended to design PACS items that would be useful across a relatively wide developmental range, and increases in autonomy observed in adolescence (Helwig, 2006) may have allowed for youth to display more of the “adult-like” active coping behaviours assessed by the PACS (e.g., purchasing products, avoiding activities). While further validation efforts are needed, our findings suggest that the PACS is valid when used with both adults and adolescent-aged participants.

Our results suggest that the PACS scales were related to maladaptation in community-dwelling families. Specifically, we found that caregivers’ and youths’ concern (as measured by the PACS) were correlated with their internalizing symptoms, as were caregivers’ avoidance behaviors. While these correlations are significant, the proportion of shared variance suggests a degree of predictive and discriminant validity, in that symptom measures (i.e., anxiety and depression) are related to, but not redundant with, the Concern and Avoidance factors. This is unsurprising given that most measures of anxiety and depression emphasize depressive or anxious cognitions and somatic symptoms, whereas PACS items focus on the frequency of pandemic-relevant behaviours that may predict the development of anxious and depressive symptoms.

Results also indicate that common pandemic-related stressors may differentially affect parent and youth adjustment. For example, examining aggregate measures of life stress, parent-reported routine disruption and COVID exposure were significantly correlated with parent-reported Concern and Avoidance respectively, while income instability was related to youth Concern. However, given that our more general measures of life stress were completed by caregivers only, these items should be expected to be more strongly related to caregivers’ symptoms. Developing a better understanding of individuals’ experience of stress during the pandemic, as well as how these relationships might differ within families, may inform preventative efforts during future pandemics; for example, parents’ PACS Concern was associated with youths’ self-reported in-person social activity during COVID. Although examining causal relationships between stress and other factors is beyond the scope of the current study, this pattern suggests that targeting parental concern may enhance social distancing practices in youth.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to create a parallel measure of pandemic-related adjustment for caregivers and youth. While some measures are designed to allow multi-informant assessment of individuals’ adjustment, parallel measures allow for comparison of behaviors between groups (e.g., Radloff 1991; Whiteside-Mansell & Corwyn, 2003). Our creation of a parallel measure for caregivers and youth will better equip studies to speak to the potential influence of parental behaviors and beliefs about the pandemic on children’s adjustment. Further, given the understandably short development time of many measures created to assess adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic, a limited number of existing measures have had their psychometric properties assessed. Having a measure of familial adjustment with an established factor structure will enhance the rigor of future studies of adjustment during future waves of COVID and other pandemics. The relative brevity of the PACS also enhances its utility as a minimally burdensome assessment tool, which is especially important in the context of the stress of a global crisis.

Based on parallel analysis, there was a slight discrepancy in the number of indicated factors between the caregiver and the youth data, with a possible third factor in the parent data consisting of items covering the purchase of supplies. In parallel analysis of caregivers’ data, this third factor could be interpreted as “stockpiling,” although it may simply function as a proxy measure of socioeconomic status (i.e., the ability to afford to stockpile goods), especially considering its significant negative correlation with parent-reported income instability. While descriptive statistics show variance in these “stockpiling” items in both caregivers and youths (see Appendices A and B), youths are likely less responsible than their caregivers for purchasing goods in their households, which may have resulted in lower endorsement of these items, contributing to reduced internal consistency. However, retaining a two-factor structure in both parents and youth enhanced parsimony and additional analyses showed high factor congruence between subsamples when using the two-factor model. We further note that, while a unified factor structure provides significant utility when examining patterns of association between caregiver and youth behaviors, we cannot assume that comparisons of mean adult and adolescent Concern and Avoidance are valid, based on current study data. Due to our relatively small sample, we were unable to test measurement invariance in our factors, whether within individuals across time or between parents and children, an important direction for future research. Similarly, our sample size was too small to partition our data for follow-up CFAs to further evaluate identified factor structures.

We assessed purchasing behaviors in youths as well, despite the fact that youth in general are less likely than caregivers to be responsible for purchasing household goods. While descriptive statistics show variance in these “stockpiling” items in youths (see Appendices A and B), the relatively low degree of these behaviors in youths may have contributed to the lower alpha of the PACS Concern scale in adolescents. While our choice to develop a pandemic-related assessment tool during a global crisis should enhance the validity of our measure, it also led to several methodological difficulties. We chose to limit the length of our measure to minimize the burden on our participants during this period of high stress, as well as to increase its utility in a repeated measures study design. While its relative brevity makes the PACS an effective tool in meeting these goals, the need for brevity limited our ability to develop a more comprehensive measure based on a large item pool. In a less stressful and time-sensitive context, initially piloting our scale with a larger pool of items would have allowed us to select items for the final scale which most closely related to constructs of interest. Similarly, we did not include distractor or attentional items to minimize participant burden during a high-stress period, which meant that we could not examine these indices of validity. Future studies including the PACS may wish to include distractor or attentional items to increase confidence in collected data, especially when used in the context of a repeated-measures study. We also acknowledge that our data was collected in an ethnically homogenous, relatively high socioeconomic status community with a low proportion of individuals meeting criteria for moderate-to-severe clinical symptoms, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Indeed, larger studies investigating larger samples have found elevated levels of COVID-related psychosocial impairment in families with lower-income, parental mental illness, and children with pre-existing physical or mental health challenges (Tso et al., 2020). Future studies with a wider catchment area may wish to investigate these demographic factors as moderators of children’s adjustment. Further, while COVID and its societal impact has reached communities worldwide, cases of COVID in our sample community were relatively limited at this point in data collection. As such, the factor structure of our questionnaire may differ depending on the demographics of a target sample, as well as the severity of the impact of COVID in that community. Within our own sample, our relatively limited sample size also prevented us from splitting our sample to conduct a complementary confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on our proposed factor structure. In future studies, researchers interested in further validating the psychometric properties of the PACS may wish to recruit a larger size or to involve a second independent sample of participants for comparison.

While many pandemic-related stressors (i.e., lockdowns, social distancing, resource scarcity) were novel, these stressors are likely to occur in future pandemics. The PACS is constructed such that the text “COVID-19” can be replaced with other diseases and may be edited accordingly for use in future pandemics (Castillo-Chavez et al., 2015; Frutos et al., 2020; Tabish, 2020). However, given that the psychometric properties of our measure were only assessed in the context of COVID-19, we cannot be sure that the factor structure will remain consistent in the face of other social or disease stressors. Future research involving the PACS in other contexts should use confirmatory factor analysis to further validate its factor structure.

In conclusion, we developed a measure designed to assess pandemic-related stress in youth and parents. Avoidance and concern factors were found in both youth and adults; these factors were meaningfully correlated with internalizing symptoms and the impact of COVID-19 on households.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Insight Grant, a BrainsCAN Accelerator grant, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) via the Canada Graduate Scholarships – Doctoral Program (CGS-D). These agencies had no role in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, report writing, or the submission of this paper for publication.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to declare.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The questionnaires and methodology for this study was approved by the Western University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (Ethics approval number: 15,121 S). Informed consent was obtained from all participating caregivers on behalf of themselves and their participating child, and assent was obtained from all participating youth.

Research Data

Data used to support the findings in this paper can be accessed via the Open Science Framework. Potentially identifying data (i.e., participant ethnicity, income, caregiver’s relationship to youth; used only in supplementary correlations) have been redacted to protect participant confidentiality.

Footnotes

In developing the item pool, two of the authors (K.L.H. and E.P.H.) contributed their expertise in the assessment of stressful life events and in the development of depression and anxiety. Another author (K.S.) contributed expertise in questionnaire development more specifically.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Andrew R. Daoust, Email: adaoust3@uwo.ca

Kasey Stanton, Email: kaseyjstanton@gmail.com.

Matthew R. J. Vandermeer, Email: mvande66@uwo.ca

Pan Liu, Email: pliu261@gmail.com.

Kate L. Harkness, Email: harkness@queensu.ca

Elizabeth P. Hayden, Email: ehayden@uwo.ca

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10862-022-09995-3.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multiinformant assessment. Burlington, VT: ASEBA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Peña S, Watamura SE, Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child abuse & neglect. 2020;110:104699. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Chavez C, Curtiss R, Daszak P, Levin SA, Patterson-Lomba O, Perrings C, Towers S. Beyond Ebola: Lessons to mitigate future pandemics. The Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(7):e354–e355. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. Perceived stress scale. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. 1994;10:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Daoust AR, Kotelnikova Y, Kryski KR, Sheikh HI, Singh SM, Hayden EP. Child sex moderates the relationship between cortisol stress reactivity and symptoms over time. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2018;87:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Lavie CJ. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2020;14(5):779–788. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn DM. Peabody picture vocabulary test. Minneapolis: Pearson Assessments; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement. 2020;52(3):177. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwart T, Konradt U. Formative versus reflective measurement: An illustration using work–family balance. The Journal of psychology. 2011;145(5):391–417. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.580388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health. 2020;14:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay LC, Arim R, Kohen D. Understanding the perceived mental health of Canadians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health reports. 2020;31(4):22–27. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202000400003-eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frutos R, Lopez Roig M, Serra-Cobo J, Devaux CA. COVID-19: the conjunction of events leading to the coronavirus pandemic and lessons to learn for future threats. Frontiers in medicine. 2020;7:223. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, D. J., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Ford, J. D., & Carter, A. S. (2020). The Epidemic–Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII). University of Connecticut School of Medicine

- Haig-Ferguson A, Cooper K, Cartwright E, Loades ME, Daniels J. Practitioner review: health anxiety in children and young people in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy. 2021;49(2):129–143. doi: 10.1017/S1352465820000636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Hayden EP. The Oxford Handbook of Stress and Mental Health. USA: Oxford University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Monroe SM. The assessment and measurement of adult life stress: Basic premises, operational principles, and design requirements. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2016;125(5):727. doi: 10.1037/abn0000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes, M. T., Szenczy, A. K., Klein, D. N., Hajcak, G., & Nelson, B. D. (2021). Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.Psychological Medicine,1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Helwig CC. The development of personal autonomy throughout cultures. Cognitive Development. 2006;21(4):458–473. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2006.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka, D., & Tomoda, A. (2020). The relationship between parenting stress and school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Horn JL. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30(2):179–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02289447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic medicine. 1979;41(3):209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbari P, Jabbari F, Ebrahimi S, Rezaei N. COVID-19: a chimera of two pandemics. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness. 2020;14(3):e38–e39. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa, A., Green, H., Compas, B., Dickey, L., & Pegg, S. (2020). Exposure to COVID-19 Pandemic Stress: Associations with Depression and Anxiety in Emerging Adults in the US. PsyArXiv. June, 29 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. J., Ward, K. P., & Rodriguez, C. (2020). Longitudinal Analysis of Short-term Changes in Relationship Conflict During COVID-19: A Risk and Resilience Perspective.Journal of Interpersonal Violence [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li J, Long X, Zhang Q, Fang X, Fang F, Lv X, Xiong N. Emerging evidence for neuropsycho-consequences of COVID-19. Current neuropharmacology. 2021;19(1):92–96. doi: 10.2174/1570159X18666200507085335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Seva U, Ten Berge JM. Tucker’s congruence coefficient as a meaningful index of factor similarity. Methodology. 2006;2(2):57–64. doi: 10.1027/1614-2241.2.2.57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magson NR, Freeman JY, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2021;50(1):44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann FD, Krueger RF, Vohs KD. Personal economic anxiety in response to COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;167:110233. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin MA, McCubbin HI. Family stress theory and assessment: The resiliency model of family stress, adjustment, and adaptation. In: McCubbin HI, Thompson A, editors. Family assessment inventories for research and practice. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison; 1991. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of youth and adolescence. 1991;20(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira SL, Morrow KE, Silk JS, Kolko DJ, Pilkonis PA, Lindhiem O. National norms and correlates of the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 in parents of school-age children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2021;30(9):2303–2314. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-02026-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli M, Lionetti F, Pastore M, Fasolo M. Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:1713. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada (2017). Immigration and diversity: Population projections for Canada and its regions, 2011 to 2036

- Tabish, S. A. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Emerging perspectives and future trends.Journal of public health research, 9(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, Asmundson GJ. Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;72:102232. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teague S, Youssef GJ, Macdonald JA, Sciberras E, Shatte A, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Hutchinson D. Retention strategies in longitudinal cohort studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC medical research methodology. 2018;18(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0586-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tso, W. W., Wong, R. S., Tung, K. T., Rao, N., Fu, K. W., Yam, J. C., & Wong, I. C. (2020). Vulnerability and resilience in children during the COVID-19 pandemic.European child & adolescent psychiatry,1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tull MT, Edmonds KA, Scamaldo KM, Richmond JR, Rose JP, Gratz KL. Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychiatry research. 2020;289:113098. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandermeer MR, Liu P, Ali OM, Daoust AR, Joanisse MF, Barch DM, Hayden EP. Orbitofrontal cortex grey matter volume is related to children’s depressive symptoms. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2020;28:102395. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside-Mansell L, Corwyn RF. Mean and covariance structures analyses: An examination of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale among adolescents and adults. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2003;63(1):163–173. doi: 10.1177/0013164402239323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.