Abstract

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) among sexual minority people has been underestimated since few decades ago despite its spreading. The current systematic review aims to review and systematize studies on factors associated with IPV perpetration within this population.

Methods

Data search was conducted on EBSCO and PubMed considering articles published until July 2022, and 78 papers were included.

Results

Although methodological limitations can affect the results found, the data demonstrated an association between IPV perpetration and psychological, relational, family of origin-related and sexual minority-specific factors, substance use, and sexual behaviors.

Conclusion

The findings emerged highlight the importance of a multidimensional approach to tackle IPV perpetration among sexual minority people and limit relapses, while increasing individual and relational wellbeing.

Policy Implications

The empirical evidence emerged can contribute to the development of policies and services tailored for sexual minority people victims of IPV, to date still scarce and often ineffective.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, IPV, IPV perpetration, Sexual minority people, Systematic review, Quantitative studies

Introduction

Couple violence suffered and perpetrated by sexual minority people1 was largely understudied until a few decades ago (Kimmes et al., 2019). In contrast, research and public opinion focused primarily on violence within heterosexual couples, influencing and being influenced by a mainstream heteronormative discourse on couple violence mainly focused on violent men who abuse their female partner because of a patriarchal and sexist culture that justify these behaviors as expression of masculinity (Rollè et al., 2020, 2021).

Nevertheless, many studies demonstrated rates of IPV among sexual minority people that are comparable, if not higher, than those identified among heterosexual couples (e.g., Walters et al., 2013; West, 2012). Establishing firm conclusions regarding the prevalence of IPV among same-sex couples seems particularly complex because of methodological limitations (e.g., lack of generalizable data, differences in the operationalization of IPV) and differences between research (Rollè et al., 2018, 2019). In addition, studies with large or representative samples have been limited and mainly conducted in US states, while data from European countries are still lacking and other research in this direction are needed. However, a representative study by Walters et al. (2013) showed alarming results: nearly one-third of sexual minority men and one-half of sexual minority women in the USA reported having suffered psychological or physical IPV in their lifetime. In addition, no significant differences emerged in the prevalence of IPV between lesbian and heterosexual women, and gay and heterosexual men (Walters et al., 2013). A meta-analysis by Badenes-Ribera et al. (2015) confirmed these results among lesbian women, finding a mean lifetime prevalence of IPV victimization of 48%.

Despite the widespread prevalence of this phenomenon, few research has been conducted on IPV among sexual minority people. A study by Edwards et al. (2015) found that only 400 (approximately 3%) out of the 14,200 studies published between 1999 and 2013 that addressed couple violence examined participants with a non-heterosexual orientation.

Although attention on couple violence among sexual minority people has increased in the last decades, the data available are still scarce, and influenced by methodological limitations. For example, most researches have used convenience samples and are cross-sectional in nature. Differences in the operative definitions of violence and sexual orientation emerged as well and make it difficult to compare results and draw firm conclusions about characteristics, antecedents, and consequences of couple violence in sexual minority people (Mason et al., 2014; Murray & Mobley, 2009).

Many similarities have been found between IPV in sexual minorities and heterosexual people such as the cycle of violence (Messinger, 2011; Walker, 1979; Whitton et al., 2019), the forms of suffered abuse (i.e., physical, psychological, sexual, and controlling violence, and unwanted pursuit), and some of the associated factors — for example, relationship satisfaction (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005), mental health (Sharma et al., 2021), personality (Landolt & Dutton, 1997), adult attachment (Bartholomew et al., 2008a, b; Gabbay & Lafontaine, 2017b), family-of-origin violence (Fortunata & Kohn, 2003), and substance abuse (Wei et al., 2020a, b).

However, peculiarities of IPV among sexual minority people emerged as well. Specifically, as highlighted in the minority stress model proposed by Meyer (1995, 2003), sexual minority people suffer particular adverse conditions (i.e., experiences of discrimination, perceived stigma, internalized homonegativity, and sexual identity concealment) that affect their individual and relational wellbeing (e.g., Hughes et al., 2022; Pachankis et al., 2021; Pachankis et al., 2018), and which seem to increase the risk to suffer or perpetrate IPV (Edwards et al., 2015; Rollè et al., 2018).

In addition, sexual minority people are affected by some specific forms of abuse: threats of outing to significant others and homonegative attitudes expressed toward the partner emerged as specific abusive tactics acted out by sexual minority persons (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2016).

Furthermore, the help-seeking process within this population is influenced by unique complexities. According to several authors (Calton et al., 2016; Cannon & Buttell, 2015; Chong et al., 2013; Ollen et al., 2017; Rollè et al., 2021), the heteronormative and homonegative climate that still permeates our societies limits the opportunity of understanding, recognizing, and managing this phenomenon. The lack of services tailored to this population and the ineffectiveness of formal sources of support have been extensively documented (Freeland et al., 2018; Lorenzetti et al., 2017; Rollè et al., 2021; Santoniccolo et al., 2021). This negatively influences the possibilities of sexual minority people who are victims or perpetrators of IPV to find help and recover from this experience.

Given similarities and differences between IPV in sexual minorities and heterosexual people, and the negative consequences this phenomenon has on victims’ physical (e.g., injuries, risk of suicidality) and psychological (e.g., symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress) wellbeing (Bartholomew et al., 2008a, b; Robinson, 2002; Strickler & Drew, 2015), understanding what variables are associated with the perpetration of IPV among sexual minority people can provide important information for clinical purposes.

Accordingly, the current paper aims to review and systematize the scientific literature focused on the exploration of factors associated to the perpetration of IPV among sexual minority people. Many studies have highlighted the lack of interventions tailored to sexual minority people who experience IPV as well as the ineffectiveness of mainstream formal sources of support, partly due by the lack of knowledge about LGBT+-related themes and specificities of IPV among sexual minorities people (see Santoniccolo et al., 2021 for a review on this topic). The implementation of policies and services capable of addressing the complexities and specificities experienced by sexual minority people involved in couple violence is still needed (Subirana-Malaret et al., 2019). Data obtained in the current review can provide empirical evidence in this direction, providing an exhaustive summary of the current knowledge on the phenomenon, which can guide the development of future prevention and intervention programs addressed to sexual minority people who perpetrate couple violence. Furthermore, the current paper aims to highlight limitations and gaps of the current literature and provide insights for future research.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Search Strategy

The current systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2009; Page et al., 2021). Two independent reviewers (TT and LR) conducted a systematic search through EBSCO (Databases: APA Psycinfo; CINAHL Complete; Family Studies Abstracts; Gender Studies Database; Race Relations Abstracts; Social Sciences Abstracts [H.W. Wilson]; Sociology Source Ultimate; Violence & Abuse Abstracts) and PubMed. No temporal limits were imposed on the search. All the articles published from the beginning of the databases to July 2022 were screened.

The following keywords were applied: violence or abuse or aggression or batter* AND partner or couple* or domestic or intimate or dating AND “same-sex” or “same-gender” or gay or lesbian* or bisex* or lgb* or homosexual* or “m*n who ha* sex with m*n” or msm or “wom*n who ha* sex with wom*n” or wsw or “m*n who ha* sex with m*n and wom*n” or msmw or “wom*n who ha* sex with wom*n and m*n” or wswm or “sexual minorit*” or “m*n who love m*n” or “wom*n who love wom*n”.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied to select the studies: (a) original research papers, (b) published in peer-review journals, (c) in the English language, (d) focused on the assessment of factors associated with the perpetration of IPV among sexual minority people (i.e., self-identified LGB+ people, people sexually or romantically attracted to people of the same-sex, people involved in same-sex relationship or people that reported non-heterosexual sexual behaviors); (e) only quantitative studies were eligible for the inclusion.

All the studies that did not match the inclusion criteria reported above were excluded. In addition, the following exclusion criteria were applied: (a) studies pertaining to IPV whose methods or results did not clearly differentiate between IPV among sexual minority people and heterosexual people; (b) validation studies, meta-analyses and literature reviews; (c) qualitative studies; (d) papers focused only on factors associated to IPV victimization among sexual minority people; (e) papers that assessed factors associated with any form of IPV (regardless of victim or perpetrator status) among sexual minority people which, however, did not differentiate between variables related to perpetration and those related to victimization. These studies were excluded because they do not provide clear information on factors associated with the perpetration of IPV, and thus do not provide data which can guide the development of interventions targeted to perpetrators. Finally, (f) articles mainly focused on transpeople or self-identified heterosexual people perpetrators of IPV were excluded. However, some of the studies included in the current systematic review involved small percentages of gender minorities or self-identified heterosexual people that based on their sexual behaviors or romantic attraction were classified as sexual minority people. These studies were retained because, from our perspective, they still provide data that can inform on factors related to IPV perpetration among cisgender sexual minority people, which was the population of our interest.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

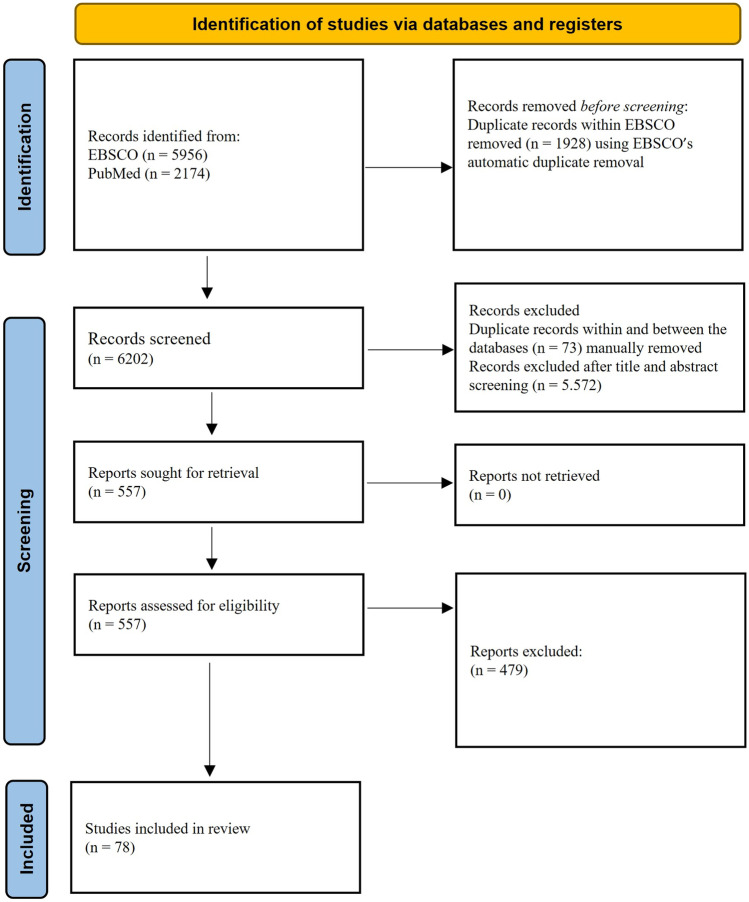

The search through EBSCO returned 5956 articles, and 4028 papers were left after duplicates removal. Of these, 414 papers were selected for full-text review after the screening of title and abstract, and 73 papers were included. PubMed provided 2174 articles in total. After the screening of title and abstract, 216 papers were selected for full-text review. The removal of duplicates between databases left 143 articles and five were included. In total, 78 articles were included in the current systematic review after full-text reading and the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Two independent reviewers analyzed the full-text and proceeded with the data extraction. Any disagreement was discussed between the reviewers in order to obtain a unanimous consensus. See Fig. 1 for a summary of the study selection procedure.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the selection procedure

Results

Seventy-eight studies were included in the current systematic review and most of them (54 studies) were conducted in the USA. Two studies were conducted in Canada, and two in the USA and Canada. Nine studies were conducted in Europe: three in Italy, two in England, one in Germany, one in Turkey and one in Spain; one study was in Turkey and Denmark. Five studies were conducted in China, one in Spanish-speaking countries (Spain, Mexico, Chile, and Venezuela), one in Latin American countries (mainly in Mexico), one in Puerto Rico, one in South Africa, and one in Hong Kong. Finally, one study assessed factors associated with IPV perpetration in the USA, Canada, Australia, UK, South Africa, and Brazil (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author(s) | Title | Country | Participants | Form(s) of IPV assessed | Assessment tool(s) | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayhan Balik and Bilgin (2021) | Experiences of minority stress and intimate partner violence among homosexual women in Turkey | Turkey | N = 149 (F) | Psychological, physical, sexual IPV, and injury | CTS2 | Outness was positively associated to physical, psychological, and sexual IPV perpetration (not to injury). Discrimination was not associated to IPV perpetration. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated only to sexual IPV perpetration |

| Bacchus et al. (2017) | Occurrence and impact of domestic violence and abuse in gay and bisexual men: a cross sectional survey | England | N = 532(M) | Negative behaviors towards the partner, defined as frightening him/her; demanding that the partner asks for permission to work, go shopping, visit relatives or visit friends; physical violence; sexual coercion | Survey developed by the authors based on Comparing Heterosexual and Same Sex Abuse in Relationships (COHSAR) survey | Depression was not associated with IPV perpetration. There was a marginal association between symptoms of mild anxiety disorder and any negative behaviors in the past 12 months, while symptoms of mild anxiety disorder were not associated with physical abuse, frightening, forcing sex, or controlling behaviors. Alcohol use was not associated with IPV perpetration. Alcohol dependence or abuse was not associated with IPV perpetration. Participants who reported frightening and physically hurting their partner were at increased risk of cannabis use compared to those who did not; there were no differences in cannabis use between those who perpetrate forcing sex or any abusive behaviors in the past 12 months, or those whose partner need to ask permission to doing activities, and those who did not; physically hurting a partner, but no other forms of abuse, was related with class A drugs use. Perpetrators of any abusive behaviors in the past 12 months were at lower risk of having a diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections (STI) than non-perpetrators; perpetrators of physical abuse, frightening, forcing sex, or controlling behaviors did not differ from those who did not perpetrate these forms of violence in the risk of having an STI diagnosis |

| Balsam and Szymanski (2005) | Relationship quality and domestic violence in women's same-sex relationship: the role of minority stress | USA | N = 272 (F) | Any IPV (physical and sexual); verbal IPV; LGB-specific tactics of psychological aggression | Conflict Tactics Scale, Revised Edition (CTS2) to assess physical/sexual and verbal IPV; 5 items developed by authors concerning LGB-specific tactics of psychological aggression | Age was not associated with IPV perpetration. Education was negatively associated with lifetime physical and sexual IPV, but not with recent IPV. Income was not associated with IPV perpetration. Dyadic adjustment was negatively associated with IPV perpetration. Gender expression was not associated with IPV perpetration. Lifetime discrimination was associated with psychological and physical/sexual (not LGB-specific abuse) IPV perpetration, while past-year discrimination was not. Experiences of discrimination were not associated with IPV perpetration. Outness was not related to IPV perpetration. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with physical/sexual IPV, and this relation was fully mediated by dyadic adjustment; internalized homonegativity was not related to psychological IPV and LGB-specific abuse |

| Bartholomew et al. (2008) | Correlates of partner abuse in male same-sex relationships | Canada | N = 186 (M) | Psychological and physical abuse | A modified version by Bartholomew et al., (2008a, b) of the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS) | Age was not associated with IPV perpetration. Less educated people were at increased risk of IPV perpetration, however, when controlling for IPV victimization this association was no longer significant. Income was negatively associated with physical, but not emotional, IPV perpetration; however, this relation was no longer significant when controlling for IPV victimization. Attachment anxiety was associated with IPV perpetration; however, only attachment anxiety assessed through interview, and not self-reported anxious attachment, was still associated with physical and psychological IPV perpetration when controlling for IPV victimization; attachment avoidance was associated with IPV perpetration, however, only attachment avoidance assessed through interview was associated with physical and psychological IPV perpetration, while self-reported attachment avoidance was not. IPV victimization was associated with IPV perpetration. Witnessing violence in the family of origin was not associated with IPV perpetration. Childhood maltreatment was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Alcohol and drug use were both positively associated with IPV perpetration; however, these relations were no longer significant when controlling for IPV victimization. HIV status was not related to IPV perpetration. Outness was positively related to IPV perpetration when controlling for internalized homonegativity, though this relation became non-significant when controlling for both internalized homonegativity and violence receipt. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Bartholomew et al., (2008a, b) | Patterns of abuse in male same-sex relationships | Canada | N = 284 (M) | Physical abuse; psychological abuse; sexual abuse; physical injury | CTS to assess physically abusive acts; 13 items derived from the latest version of the CTS and the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory both used to assess psychological abuse; 7 items developed by the authors, of which 2 used to assess sexual abuse and 5 used to assess physical injury | IPV victimization was associated with IPV perpetration. Psychological, sexual, and psychological IPV, and physical injury were associated with each other, however, the association between physical IPV and physical injury was no longer significant when controlling for IPV victimization |

| Bogart et al. (2005) | The association of partner abuse with risky sexual behaviors among women and men with HIV/AIDS | USA | N = 726, 286 (F), 440 (M) | Any IPV (threats to hurt the partner, physical violence, and sexual coercion) | 8 items developed by the authors | Unprotected sex was associated with IPV perpetration |

| Carvalho et al. (2011) | Internalized sexual minority stressors and same-sex intimate partner violence | USA | N = 567, 262 (F), 305 (M) | Any IPV | 1 item developed by the authors | Perceived stigma was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Neither outness nor internalized homonegativity were related to IPV perpetration |

| Causby et al. (1995) | Fusion and conflict resolution in lesbian relationships | USA | N = 275 (F) | Verbal aggression, physical aggression, physical violence | CTS | Self-esteem was negatively associated with IPV perpetration. Share fusion was associated with physical aggression, physical/more severe violence, and psychological violence, while time fusion was only associated with physical aggression and psychological violence |

| Chong et al. (2013) | Risk and protective factors of same-sex intimate partner violence in Hong Kong | Hong Kong | N = 306, 192 (F), 114 (M) | Psychological aggression and physical assault | CTS2 | No gender differences in IPV perpetration were found; Age was not associated with IPV perpetration. Sexual orientation was not associated with IPV perpetration. Less educated people were at increased risk of IPV perpetration. Income was negatively associated with physical, but not sexual, IPV perpetration. Anger management was negatively associated with physical and psychological IPV perpetration, and the relation between anger management and physical IPV perpetration was fully mediated by psychological IPV. Self-efficacy was not associated with IPV perpetration. Cohabitation with a same-sex partner was not associated with physical or psychological IPV perpetration. Length of relationship was not associated with IPV perpetration. Dominance was positively associated with IPV perpetration; however, this relation was no longer significant when controlling for demographic variables. Relationship conflict was positively associated with physical and psychological IPV. Physical and psychological aggressions were positively correlated. Substance use (i.e., both alcohol and other drugs use) was positively associated with physical, but not psychological, IPV perpetration. Internalized homonegativity was not associated with IPV perpetration |

| Craft and Serovich (2005) | Family-of-origin factors and partner violence in the intimate relationships of gay men who are HIV positive | USA | N = 51 (M) | Physical assault, psychological aggression, sexual coercion, physical injury | CTS2 | Witnessing violence from mother-to-father was positively associated with sexual coercion, while witnessing violence from father-to-mother was not. Witnessing violence (both from mother-to-father and from father-to-mother) was not associated with psychological IPV, physical assault or physical injury perpetration |

| Craft et al. (2008) | Stress, attachment style, and partner violence among same-sex couples | USA | N = 87, 46 (M), 41 (F) | Psychological aggression; physical aggression; sexual coercion | CTS2 | No gender differences in IPV perpetration were found. Perceived stress was positively associated with IPV perpetration, and this relation was fully mediated by insecure attachment |

| Davis et al. (2016) | Associations between alcohol use and intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men | USA | N = 189 (M) | Physical and sexual, monitoring, controlling, HIV related-IPV, and emotional violence + a total score (any IPV) | IPV-GBM Scale | Alcohol use was associated with physical/sexual and emotional IPV toward both regular and casual partner, and with controlling and HIV-related IPV perpetration toward regular, but not casual, partner; monitoring IPV perpetration was not associated with alcohol use |

| Derlega et al. (2011) | Unwanted pursuit in same-sex relationships: effects of attachment styles, investment model variables, and sexual minority stressors | USA | N = 153, 84 (F), 66 (M), 3 (unidentified) | UPB perpetration; aggressive behaviors | The 28-item Relational Pursuit–Pursuer Short Form Questionnaire | Men engaged in more pursuit behaviors than women did. No gender differences were found regarding aggressive behaviors. Attachment anxiety was associated with perpetration of pursuit behaviors, but not with aggressive behaviors; attachment avoidance was not associated with pursuit or aggressive behaviors. Relationship satisfaction was not associated with perpetration of pursuit or aggressive behaviors. Higher scores in investment size, not in poor quality of alternatives or commitment in relationships, were related to perpetration of unwanted pursuit behaviors (and not with aggressive behaviors). Frequency of minority stressors experienced was not associated with perpetration of pursuit behaviors or negative behaviors |

| Edwards et al. (2021) | Minority stress and sexual partner violence victimization and perpetration among LGBQ + college students: the moderating roles of hazardous drinking and social support | USA | N = 1221, 885 (F), 175 (M), 119 (gender queer, gender nonconforming, or nonbinary), 32 (transgender), 4 (other), 6 (not disclosed) | Sexual IPV | SGM-CTS2 | IPV perpetration was positively related to IPV victimization. IPV perpetration was unrelated to problem drinking, minority stress, or social support. Minority stress (identity concealment; internalized homonegativity; stigma consciousness) was not related to perpetrating IPV. Problem drinking moderated the relation between minority stress and IPV perpetration: among those with higher levels of problem drinking, minority stress was associated with a higher likelihood of perpetration, while this relation was not significant at low levels of problem drinking. Social support did not moderate this relation |

| Edwards and Sylaska (2013) |

The Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence among LGBTQ College Youth: The Role of Minority Stress |

USA |

N = 391, 191 (M), 178 (F), 18 (genderqueer), 4 (other) |

Physical, sexual and psychological abuse | CTS2 | Experiences of discrimination were not associated with IPV perpetration. Internalized homonegativity was associated with physical and sexual IPV perpetration, but not with psychological IPV |

| Finneran and Stephenson (2014) | Intimate partner violence, minority stress, and sexual risk-taking among U.S. men who have sex with men | USA | N = 1575(M) | Physical and sexual IPV | 2 items developed by the authors | Age was not associated with IPV perpetration. Sexual orientation was not associated with IPV perpetration. Ethnicity was not associated with IPV perpetration. Education was negatively associated with physical, but not sexual, IPV perpetration. Employment was not associated with IPV perpetration. Sexual IPV perpetration was associated with psychological, but not physical, IPV perpetration; psychological IPV perpetration was associated with physical IPV perpetration. HIV status was not related to IPV perpetration. Perpetrators of physical IPV were more likely to have had unprotected anal intercourse than non-perpetrators of physical IPV; no differences in unprotected anal intercourse emerged between perpetrators of sexual IPV and non-perpetrators of sexual IPV; physical IPV, but not sexual IPV, was higher among participants who have had unprotected anal intercourses (UAI) compared with those who have not had. Homophobic discrimination was positively associated with IPV perpetration in the ANOVA test, while this relation was not significant in the logistic model. Internalized homonegativity was associated with sexual IPV, but not with physical IPV, perpetration |

| Finneran et al. (2012) | Intimate partner violence and social pressure among gay men in six countries | USA, Canada, Australia, the UK, South Africa, and Brazil | N = 2368 (M) | Physical and sexual violence | 2 items developed by the authors | Age was associated with sexual IPV perpetration only in USA (participants aged between 25 and 34 were at increased risk of IPV) and Australia (participants older than 34 were at increased risk of IPV), and not in Canada, Brazil, South Africa, UK. Education was associated with IPV perpetration only in Canada: those who had more than 12 years of education were less likely to perpetrate IPV. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with IPV only in United Kingdom. Ethnicity, HIV status, drug use, behavioral bisexuality, homophobic discrimination, and heteronormativity were not associated with IPV |

| Fontanesi et al. (2020) | The role of attachment style in predicting emotional abuse and sexual coercion in gay and lesbian people: an explorative study | Italy | N = 182, 106 (F), 76 (M) |

Emotional abuse (restrictive engulfment, denigration, hostile withdrawal, and dominance/intimidation); sexual coercion |

The Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse to assess emotional abuse; The Sexual Coercion in Intimate Relationship Scale to assess sexual coercion | No gender differences in IPV perpetration were found. Confidence was negatively associated with commitment defection and manipulation, but not with coercion of resources and violence; a positive association was found between confidence and acted emotional abuse; discomfort with closeness was negatively associated with coercion of resources and violence, but was not related to commitment defection, manipulation, and acted emotional abuse; need for approval was negatively related to coercion of resources and violence, and manipulation, but not with commitment defection or acted emotional abuse; preoccupation with relationship was positively related to commitment defection, and negatively associated to coercion of resources and violence, manipulation, and acted emotional abuse; relationship being secondary was not associated with sexual coercion or acted emotional abuse |

| Fortunata and Kohn (2003) | Demographic, psychosocial, and personality characteristics of lesbian batterers | USA | N = 100 (F); perpetrators = 38, non-perpetrators = 62 | Physical violence | The CTS-L (Lesbian): Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979) as modified by Coleman (1991) for lesbian couples | Ethnicity was not associated with IPV perpetration. Batterers’ partners had lower income than non-batterers' partners. Employment was not associated with IPV perpetration. Batterers had higher scores on the aggressive (sadistic), antisocial, avoidant, passive-aggressive, self-defeating, borderline, paranoid, and schizotypal personality scale scores and higher alcohol-dependent, drug-dependent, bipolar (manic syndrome), and delusional clinical syndrome scale scores; however, no significant differences between batterers and non-batterers emerged in the scores on compulsive, dependent, depressive, histrionic, narcissistic, schizoid, anxiety, dysthymia, PTSD, somatoform, major depression, and thought disorders scales; when controlling for desirability and debasement, group differences for the avoidant, bipolar (manic syndrome), dependent, passive-aggressive, schizoid, schizotypal, and self-defeating personality were no longer significant. Having a child was not associated with IPV perpetration. Batterers and non-batterers did not differ regarding monogamous relationships. Childhood maltreatment was positively associated with IPV perpetration. There were no differences between abusers and non-abusers in having a family member during childhood who abused substances. Alcohol use, alcohol dependence or abuse, and drug use were positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Gabbay and Lafontaine (2017a) | Do trust and sexual intimacy mediate attachment’s pathway toward sexual violence occurring in same sex romantic relationships? | Canada and USA | N = 310, 107 (M), 203 (F) | Sexual violence | CTS2 | Attachment anxiety was associated with sexual IPV perpetration; this association was fully mediated by dyadic trust and sexual intimacy in a serial mediation model; attachment avoidance was associated with sexual IPV perpetration, and this relation was partially mediated by dyadic trust and sexual intimacy in a serial mediation model |

| Gabbay and Lafontaine (2017b) | Understanding the relationship between attachment, caregiving, and same sex intimate partner violence | Canada and USA | N = 310, 107 (M), 203 (F) | Psychological and physical violence | CTS2 | No gender differences in IPV perpetration were found. Attachment anxiety was not associated with IPV perpetration; attachment avoidance was associated with physical, but not psychological, IPV perpetration, and this relation was no longer significant when controlling for receipt of violence; the proximity dimension of caregiving (and not sensitivity, compulsive caregiving and controlling caregiving) was negatively associated with physical and psychological IPV perpetration, although this relation was not significant when controlling for receipt of violence; a significant association was found between psychological IPV perpetration and both hyperactivation of the attachment and caregiving systems and deactivation of the attachment and caregiving systems, even in the presence of each other. Regarding physical IPV perpetration, only hyperactivation was still associated with physical couple violence when controlling for the effect of deactivation strategies. None of these findings were significant when receipt of violence was controlled for. IPV victimization was associated with IPV perpetration |

| Jacobson et al. (2015) | Gender expression differences in same-sex intimate partner violence victimization, perpetration, and attitudes among LGBTQ college students | USA | N = 278, 115 (M), 163 (F) | Any IPV (physical and sexual violence); psychological abuse | The Perpetration in Dating Relationships (PDR) to assess physical and sexual violence; The Safe Dates—Psychological Abuse Perpetration scale (SD-PAP) to assess psychological abuse | Masculinity was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Jones and Raghavan (2012) | Sexual orientation, social support networks, and dating violence in an ethnically diverse group of college students | USA | N = 114, 60 (M), 54 (F) | Physical dating violence; sexual dating violence | CTS2 | Being involved in a male network composed by perpetrators of violence was positively associated with dating or sexual violence only among lesbian women and not among gay men |

| Kahle et al. (2020) | The influence of relationship dynamics and sexual agreements on perceived partner support and benefit of PrEP use among same-sex male couples in the U.S | USA | N = 659 (M) | Any IPV (physical, sexual, monitoring, controlling and emotional) | IPV-GBM Scale | IPV perpetrators did not differ with non-perpetrators in thinking their partner would not support their PrEP use or in not knowing if their partner would support their PrEP use, or in their perception of benefits provided by PrEP use |

| Kelley et al. (2014) | Predictors of perpetration of men’s same-sex partner violence | USA | N = 107 (M) | Physical violence | CTS2 | Alcohol use was associated with IPV perpetration, and this relation was moderated by outness: only at high levels of outness, this association was significant. IPV perpetrators have lower levels of outness compared with non-perpetrators. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Kelly et a;. (2011) | The intersection of mutual partner violence and substance use among urban gays, lesbians, and bisexuals | USA | N = 2200, 1782 (M), 418 (F) | Physical and non-physical (verbal threats, property destruction) violence | 1 measure developed by the authors | Alcohol and drug use were not associated with IPV perpetration |

| Krahé et al. (2000) | Ambiguous communication of sexual intentions as a risk marker of sexual aggression | Germany | study 1: N = 526, 283 (F), 243 (M); study 2: N = 454, 173 (F), 281 (M) | Sexual aggression | The Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) | Token resistance was positively associated with sexual violence, while the association between sexual violence and compliance was not significant |

| Landolt and Dutton (1997) | Power and personality: an analysis of gay male intimate abuse | USA | N = 52 same-sex couples | Physical abuse; emotional abuse | CTS to assess physical abuse; Psychological Maltreatment Inventory (PMI), used to assess emotional abuse | Both actor’s and partner’s abusive personality was associated with physical and psychological IPV perpetration; more specifically, each constituent of the abusive personality of both the actor and the partner were associated with psychological IPV perpetration; for physical IPV perpetration both actor and partner effects were significant for BPO, fearful, and preoccupied attachment, while neither actor nor partner effects were significant for anger and paternal rejection, and only actor effects were significant for maternal rejection. Both actor’s and partner’s abusive personality was associated with physical and psychological IPV perpetration; more specifically, each constituent of the abusive personality of both the actor and the partner were associated with psychological IPV perpetration; for physical IPV perpetration both actor and partner effects were significant for BPO, fearful, and preoccupied attachment, while neither actor nor partner effects were significant for anger and paternal rejection, and only actor effects were significant for maternal rejection., perpetration of psychological IPV by abusers was higher when victims perceive to be in a divided-power couple compared when victims perceived to be in an egalitarian couple. No other differences regarding psychological IPV perpetration emerged when comparing victims’ perception of being in a divided-power, egalitarian or self-dominant couple; couples that disagree in their perception of relationship power dynamics (i.e., non-congruent couples) did not differ from congruent couple in their levels of IPV perpetration |

| Leone et al. (2022) | A dyadic examination of alcohol use and intimate partner aggression among women in same-sex relationships | USA | N = 163 couples (F) | Physical and psychological IPV | CTS2, PMWI | Participants’ drink per week (DPW) consumed were positively related to one's own physical, but not psychological, IPV perpetration. Partner's DPW was associated with participants’ psychological, but not physical, IPV perpetration. Participants’ hazardous alcohol use was associated with both physical and psychological IPV perpetration, while partner's hazardous drink use was associated only to psychological IPV perpetration |

| Lewis et al. (2017) | Empirical investigation of a model of sexual minority specific and general risk factors for intimate partner violence among lesbian women | USA | N = 1048 (F) | Psychological aggression (dominance-isolation (e.g., jealousy, treating as an inferior, and isolation from resources) and emotional-verbal violence (e.g., name calling, screaming, and swearing); physical violence |

The 28-item short form of the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI) to assess psychological aggression; the 12 physical assault items from the CTS2 to assess physical violence |

While physical violence perpetration and victimization were each other associated, only the association between psychological IPV perpetration and psychological IPV victimization was significant, but the opposite directional path was not. A complex relation between discrimination, internalized homonegativity, perpetrator trait anger, perpetrator’s and partner’s alcohol problems, perpetrator’s relationship dissatisfaction, and psychological and physical violence |

| Lewis et al. (2018) | Discrepant drinking and partner violence perpetration over time in lesbians’ relationships | USA | N = 1052(F) | Physical assault; psychological maltreatment | 12 items from the physical assault subscale and six items from the Injury subscale of the CTS2 for physical aggression; the short form of the PMWI for psychological aggression | Physical aggression was associated with discrepant drinking between partners at a later time point, while discrepant drinking was not related to subsequent physical aggression; discrepant drinking was associated with subsequent psychological aggression and vice versa |

| Li et al. (2019) | Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among same-sex couples: the mediating role of intimate partner violence | USA | N = 144 same-sex couples | Physical IPV; psychological IPV | The Conflict Tactics Scale-Couple Form Revised (CTS-CF-R) | Relationship satisfaction was negatively associated with psychological, but not physical, IPV perpetration. Participants’ and partner’s internalized homonegativity were associated with psychological, but not physical, IPV |

| Li et al. (2022) | Sexual minority stressors and intimate partner violence among same-sex couples: commitment as a resource | USA | N = 144 couples, 109 (F), 35 (M) | Physical and psychological IPV | The Conflict Tactics Scale-Couple Form Revised (CTS-CF- R; Straus et al., 1996) | Internalized homophobia and discrimination were positively associated to IPV perpetration, while commitment in the relationship was negatively associated to IPV perpetration. Commitment moderated the association between internalized homonegativity and partner's (not participants’) psychological (not physical) IPV perpetration: when commitment was high, this association was no longer significant. No other moderating effects of commitment on the association between internalized homonegativity and participants’ or partner’s IPV perpetration were found. Own’s commitment (not partner's commitment) moderated the association between own’s discrimination (not partner's discrimination), and participants’ and partner’s psychological IPV perpetration prevalence and frequency: at high levels of commitment these relations were no longer significant. No other moderating effects of own’s or partner’s commitment in the relation between own’s or partner’s discrimination and participants’ or partner’s IPV perpetration prevalence or frequency were found. Individuals’ (not partner's) internalized homophobia was positively related to a higher frequency (not prevalence) of individuals’ own and the partner’ psychological (not physical) IPV perpetration through lower levels individuals own’ commitment (not through partner's commitment). Individuals’ discrimination (not partner’s discrimination) was negatively related to frequency (not prevalence) of individual's own and the partner’s psychological (not physical) IPV perpetration through higher levels of partner’s commitment (not individual's own commitment). Individuals’ (not partner’s) internalized homophobia was positively related to individual’s own and the partner’s physical (not psychological) IPV perpetration through lower levels of individual’s own commitment. Individuals’ (not partner’s) discrimination was negatively related to lower likelihood of individuals’ own and the spouses’ physical (not psychological) IPV perpetration through higher levels of partner’s (not individual's own) commitment. No other mediating effects of commitment on IPV perpetration were detected |

| Li & Zheng (2021) | Intimate partner violence and controlling behavior among male same-sex relationships in China: relationship with ambivalent sexism | China | N = 272 (M) | Psy, phys, sex, inj; cold violence (economic and personal control, emotional and sexual negligence); dominance, emotional control, financial control, intimidation, social/isolation, and threats | CTS2S; Cold Violence Scale; 34-item scale designed by the researchers | Number of sexual partner was positively related only to perpetration of emotional negligence, emotional control, and threats, but not to psychological, physical, sexual IPV, and injury, economic and personal control, dominance, financial control, intimidation, social/isolation. Both benevolent and hostile sexism toward women was positively associated to Cold Violence perpetration, but not to IPV or controlling behaviors perpetration. Hostile attitudes toward men were positively related only to controlling behaviors perpetration, while Hostile sexism toward men was not associated to IPV perpetration, cold violence, or controlling behaviors |

| Longares et al. (2018a) | Insecure attachment and perpetration of psychological abuse in same-sex couples: a relationship moderated by outness | Spanish-speaking people who were mostly residents in Spain (44.26%), Mexico (20%), Chile (8.5%), and Venezuela (8.5%) | N = 305, 157 (M), 148 (F) | Psychological abuse | Adaptation of the 19 items on the Psychological Abuse in Intimate Partner Violence Scale (EAPA-P) | Insecure adult attachment was associated with psychological IPV; outness moderated this relation: at low levels of overall outness, the relationship between insecure attachment and psychological IPV was not significant; similarly, at low and high levels of outness to religion this association was not significant; outness to the family did not moderate the association between insecure attachment and psychological IPV. Overall outness, and not outness to religion and outness to the family, was positively related to psychological IPV perpetration |

| Longares et al. (2018b) | Psychological abuse in Spanish same-sex couples: prevalence and relationship between victims and perpetrators | Spain | N = 107, 54 (M), 53 (F) | Psychological abuse | Items developed by authors | No gender differences in IPV perpetration were found. IPV victimization was associated with IPV perpetration |

| Mason et al. (2016) | Minority stress and intimate partner violence perpetration among lesbians: negative affect, hazardous drinking, and intrusiveness as mediators | USA | N = 342 (F) | Physical IPV | CTS2 | A complex relation between general life stress, distal and proximal minority stressors, negative affect, hazardous alcohol use, intrusiveness, and physical IPV perpetration was detected |

| McKenry et al. (2006) | Perpetration of gay and lesbian partner violence: a disempowerment perspective | USA | N = 77, 40 (M), 37 (F) | Physical violence | CTS2 | Non-perpetrating females reported higher psychological adjustment compared with non-perpetrating males, and male and female perpetrators. IPV perpetrators experienced more family stress than non-perpetrators. Self-esteem was negatively associated with IPV perpetration. Perpetrators have less secure attachment style than non-perpetrators. Relationship satisfaction was not associated with IPV perpetration. Dependence was not related to IPV perpetration. Perceived power differentials were not associated with IPV perpetration. Masculinity was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Witnessing violence in the family of origin was not associated with IPV perpetration. Perpetrators of IPV grew up in lower SES families than non-perpetrators. Alcohol use was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Messinger et al. (2021) | Sexual and gender minority intimate partner violence and childhood violence exposure | USA | N = 457 (FAB SGM) | Physical and psychological violence | Two items developed by the authors | Older and Black and Latin participants were more likely to perpetrate IPV than younger and White participants. Parental verbal and physical IPV were positively associated to psychological e physical IPV. Childhood sexual abuse was related only to physical IPV perpetration. To witness violence between siblings was positively associated only to psychological IPV perpetration; to witness parental violence to both physical and psychological IPV. Gender of perpetrator of violence in the family of origin was not associated to IPV perpetration |

| Milletich et al. (2014) | Predictors of women’s same-sex partner violence perpetration | USA | N = 209 (F) | Physical violence | CTS2 | Less educated people were at increased risk of IPV perpetration. Fusion was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Dominance/accommodation was not directly associated with IPV perpetration; however, an indirect relation mediated by fusion was found between these variables. Witnessing violence in the family of origin was not associated with IPV perpetration. Internalized homonegativity was not directly related to IPV perpetration, while there was a positive indirect association between these variables that was mediated by fusion |

| Miltz et al. (2019) | Intimate partner violence, depression, and sexual behavior among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in the PROUD trial | England | N = 436 (M) | Any IPV (psychological, physical and sexual) | 10 items developed by the authors | Sexual orientation was not associated with IPV perpetration. Ethnicity was not associated with IPV perpetration. Less educated people were at increased risk of IPV perpetration. Employment was not associated with IPV perpetration. Depression was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Drug use during sex was associated with IPV perpetration. Years at anal sexual debut and number of sexual partners were not associated with IPV. perpetration. Having group sex was associated with perpetration of lifetime, but not past year, IPV. Unprotected sex was not associated with IPV perpetration. Outness was not related to IPV perpetration. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Oringher and Samuelson (2011) | Intimate partner violence and the role of masculinity in male same-sex relationships | USA | N = 117 (M) | Physical assault, sexual coercion and injury | CTS2 | A positive association was found between physical IPV victimization and physical IPV perpetration, and between sexual IPV victimization and sexual IPV perpetration; sexual and physical IPV perpetration were positively associated. Several dimensions of masculinity were associated with physical IPV perpetration: suppression of vulnerability and aggressiveness were both positively related to physical IPV perpetration, while avoidance of dependency on other was negatively related to physical IPV perpetration; the association between self-destructive achievement and dominance, and physical IPV perpetration was not significant; no dimensions of masculinity were associated with sexual IPV perpetration |

| Pepper and Sand (2015) | Internalized homophobia and intimate partner violence in young adult women’s same-sex relationships | USA | N = 40 (F) | Physical aggression, psychological assault, sexual coercion, injury | CTS2 | Psychological maladjustment was positively associated with psychological, but not physical or sexual, IPV perpetration. Hostility was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Emotional instability was positively related to physical and psychological IPV perpetration, but not with sexual IPV. Negative worldview was associated with psychological, but not physical or sexual, IPV perpetration. Emotional unresponsiveness was not associated with IPV perpetration. Negative self-esteem and self-adequacy were not associated with IPV perpetration. Dependence was not related to IPV perpetration. Physical IPV victimization was associated with physical IPV perpetration; psychological IPV victimization was associated with psychological IPV perpetration; sexual IPV victimization was not associated with sexual IPV perpetration. Sexual coercion perpetration was associated only with the religious attitudes toward Lesbianism dimension of the Lesbian Internalized Homonegativity Scale (LIHS), while it was not related to any other dimension of the LIHS. Internalized homonegativity was not related to physical and emotional IPV perpetration |

| Pistella et al. (2022) | Psychosocial impact of Covid-19 pandemic and same-sex couples conflict: the mediating effect of internalized sexual stigma | Italy | N = 232, 131 (F), 101 (M) | Any IPV | CTS2S | Couple conflict and IPV victimization were positively related to IPV perpetration; sexual satisfaction was negatively related to IPV perpetration. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19, age, internalized sexual stigma, relationship duration, religiosity, and involvement in LGB associations were not related to IPV perpetration |

| Poorman and Seelau (2001) | Lesbians who abuse their partners: using the FIRO-B to assess interpersonal characteristics | USA | N = 15 (F) | Psychological abuse | The Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation-Behavior (FIRO-B) | Perpetrators had lower expressed and wanted inclusion, and expressed and wanted affection compared with non-perpetrators; However, expressed and wanted control did not differ between perpetrators and non-perpetrators, and there were no differences between the groups in the differences between expressed and wanted inclusion, expressed and wanted affection or expressed and wanted control |

| Reuter et al. (2015) | An exploratory study of teen dating violence in sexual minority youth | USA | N = 782, 444 (M), 338 (F) | Physical, psychological, sexual, and relational violence | The Conflict in Adolescent Dating and Relationship Inventory (CADRI) | No gender differences in IPV perpetration were found. Sexual orientation was associated with severe, and not any, TDV perpetration. Hostility was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Social support was not related to IPV perpetration. Witnessing violence in the family of origin was not associated with IPV perpetration. Alcohol use was not associated with IPV perpetration |

| Schilit et al. (1990) | Substance use as a correlate of violence in intimate lesbian relationships | USA | N = 107 (F) | Any IPV (sexual, physical and emotional) | A questionnaire developed by the authors | Participants’ alcohol use, but not partner's alcohol use, was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Participants’ and partner's drug use were not associated with IPV perpetration |

| Schilit et al. (1991) | Intergenerational transmission of violence in lesbian relationships | USA | N = 104 (F) | Sexual, verbal-emotional and physical abuse | A 70-items questionnaire developed by the authors | Witnessing intimate partner violence in the family of origin was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Childhood maltreatment was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Sharma et al. (2021) | Sexual agreements and intimate partner violence among male couples in the U.S.: an analysis of dyadic data | USA | N = 386 same-sex couples | Physical, sexual, monitoring, controlling and emotional IPV | IPV-GBM Scale | Depression was positively associated with IPV perpetration; however, this association was not significant among couples who stipulated a sexual agreement. Length of relationship was not associated with IPV perpetration. Participants’ and partner's alcohol or drug use were not associated with IPV perpetration |

| Stephenson and Finneran (2016) | Minority stress and intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men in Atlanta | USA | N = 1075(M) |

Physical/sexual, monitoring, controlling, HIV-related and emotional IPV |

IPV-GBM Scale | HIV status was not related to IPV perpetration. Homonegativity was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Stephenson and Finneran (2017) | Receipt and perpetration of intimate partner violence and condomless anal intercourse among gay and bisexual men in Atlanta | USA | N = 1100 (M) | Physical/sexual, monitoring, controlling and emotional violence | IPV-GBM Scale | Condomless anal intercourse was associated with physical, sexual, emotional, and controlling IPV, while not with monitoring IPV |

| Stephenson et al., (2011a) | Intimate partner violence and sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men in South Africa | South Africa | N = 521 (M) | Physical and sexual IPV | 2 items developed by the authors | Age was not associated with IPV perpetration. Non-White participants were at increased risk of IPV perpetration. Less educated people were at increased risk of IPV perpetration. Number of gay friends was not associated with physical IPV perpetration. Having had partner of both sexes or only female partners, or having sex with partners other than the main partner were not related to IPV perpetration. Use of lubrification was not associated with physical IPV perpetration. Perpetrators of physical IPV were more likely to have had unprotected anal intercourse than non-perpetrators of physical IPV; no differences in unprotected anal intercourse emerged between perpetrators of sexual IPV and non-perpetrators of sexual IPV; both sexual and physical IPV were higher among participants who have had unprotected anal intercourses (UAI) compared with those who have not. Perceived stigma was not associated with IPV perpetration. Gay identity development was not related to IPV perpetration |

| Stephenson et al., (2011b) | Dyadic characteristics and intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men | USA | N = 528(M) | Emotional, physical, and sexual IPV | Four items from the Psychological Abuse scale from CTS2 to assess emotional IPV; six items developed by the authors were used to assess physical violence; three items developed by the authors were used to assess sexual coercion | Age and age differences between the partners were not associated with IPV perpetration. Ethnicity was not associated with IPV perpetration. Education was negatively associated with emotional and sexual, but not physical, IPV perpetration. Relationship satisfaction was negatively associated with psychological, but not physical or sexual, IPV perpetration. Perpetrators of emotional or physical violence showed lower levels of communal coping, couple efficacy, and couple outcome preferences; in addition, perpetrators of emotional abuse (not those who perpetrated physical or sexual abuse) had lower degree of concordance with the partner lifestyle topics. Perpetrators of sexual violence had lower communal coping scores compared with non-perpetrators, while they did not differ in couple efficacy and couple outcome preferences. Participants who reported to be HIV-positive were at increased risk of physical, but not emotional or sexual, IPV perpetration. There was a negative association between sexual IPV perpetration and perceived local stigma-couple, but not with perceived local stigma-individual. No significant associations between perceived local stigma and physical or emotional IPV perpetration were found |

| Stephenson et al. (2013) | Dyadic, partner, and social network influences on intimate partner violence among male–male couples | USA | N = 403 (M) | Physical and sexual violence | 2 items developed by the authors | Having assertiveness abilities reduced the probability to perpetrate sexual coercion. Sexual victimization in the family of origin was associated with sexual IPV perpetration, while suffering physical and psychological victimization in the family of origin were not |

| Stults et al. (2021a) | Determinants of intimate partner violence among young men who have sex with men: the P18 cohort study | USA | N = 526 (M) | Physical, psychological, and sexual IPV | Three yes–no questions | Latin participants were at increased risk of IPV perpetration compared to White and Black participants. IPV perpetration was positively associated to lifetime IPV, relationship status, depression, personal gay-related stigma, and marijuana and other substance use. In contrast, SES, childhood mistreatment, impulsivity, PTSD, public gay-related stigma, and alcohol use were not associated to IPV perpetration |

| Stults et al., (2015a) | Intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization among YMSM: the P18 cohort study | USA | N = 600 (M) | Any IPV (verbal abuse, physical violence, sexual coercion) | 3 items developed by the authors | Depression was positively associated with IPV perpetration; however, this relation was no longer significant when controlling for childhood maltreatment. PTSD and loneliness were positively associated with IPV perpetration at a bivariate level; however these relations were not significant in the regression model when controlling for childhood maltreatment. Impulsivity was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Involvement in LGB + support agencies was positively associated with IPV perpetration. IPV victimization was associated with IPV perpetration. Childhood maltreatment was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Personal-local stigma was positively associated with IPV perpetration, while the relation between public-gay related stigma and IPV was not significant |

| Stults et al. (2016) | Intimate partner violence and sex among young men who have sex with men | USA | N = 528(M) | Any IPV (physical, sexual and emotional) | A modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale by Feldman et al. (2007) | Participants who reported two or more instances of anal receptive and insertive sex had higher risk of perpetrating couple violence compared with those who reported no instances of these behaviors. Unprotected sex was associated with IPV perpetration |

| Stults et al. (2015b) | Intimate partner violence and substance use risk among young men who have sex with men: The P18 cohort study | USA | N = 528(M) | Any IPV (physical, sexual and emotional) | A modified version of the conflict tactics scale by Feldman et al. (2007) | Alcohol use was not associated with IPV perpetration. Drug use was positively related to IPV perpetration |

| Stults et al., (2021b) | Sociodemographic differences in intimate partner violence prevalence, chronicity, and severity among young sexual and gender minorities assigned male at birth: the P18 cohort study | USA | N = 665 (AMAB) | Physical, sexual, psychological, any IPV, injury | CTS2 | Transgender participants reported higher levels of severe injury perpetration prevalence (not minor injury, physical, psychological, and sexual IPV) than cisgender participants. Cisgender people reported higher levels of minor sexual IPV perpetration chronicity (the groups did not differ on the other forms of violence perpetrated in terms of prevalence or chronicity). Asian participants had higher levels of minor sexual IPV perpetration prevalence than White participants, while they did not differ from Latin, Black, and multiracial participants. No other differences between ethnic groups emerged on IPV perpetration prevalence. White and Black reported higher levels of minor sexual IPV perpetration chronicity than Asian participants. No other differences between ethnic groups emerged on IPV perpetration chronicity. Bisexual people reported higher levels of injury and severe sexual IPV perpetration prevalence than gay people; no other differences emerged between bisexual and gay participants in terms of IPV prevalence or chronicity. Participants who earned less than $5000 were less like to report minor psychological perpetration prevalence but more likely to report severe injury and sever sexual IPV perpetration prevalence than those who earned less. Participants who earned less than $5.000 were less likely to report minor sexual IPV perpetration chronicity than participants who earned less. No other differences emerged in IPV prevalence or chronicity between these two groups. Education was not related to IPV perpetration prevalence, while non-graduate students reported higher levels of minor psychological IPV perpetration chronicity than graduate students. No other differences emerged between these two groups |

| Suarez et al. (2018) | Dyadic reporting of intimate partner violence among male couples in three U.S. cities | USA | N = 160 same-sex couples | Physical/sexual, monitoring, controlling, HIV-related and emotional IPV | Intimate Partner Violence Among Gay and Bisexual Men (IPV-GBM) Scale | Age was negatively associated with IPV perpetration. Cohabitation was associated with increased risk of IPV perpetration. Participants’ Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with IPV perpetration, while partner’s internalized homonegativity was not |

| Swann et al. (2021) | Intersectional minority stress and intimate partner violence: the effects of enacted stigma on racial minority youth assigned female at birth | USA | N = 249 (FAB) | Severe psychological violence, severe physical violence, and sexual IPV; SGM-Specific IPV tactics | SGM-CTS2; SGM-Specific IPV Tactics Scale | Heterosexist enacted stigma was positively related to psychological and sexual IPV perpetration, but not to physical or sexual and gender minority-specific IPV. Racist enacted stigma was positively related to physical and sexual IPV perpetration. Heterosexist stigma moderated the association between racist enacted stigma and psychological IPV perpetration: this relation was significant only at low and mean levels of heterosexist stigma, while at high levels of heterosexist discrimination it was not significant. Heterosexist stigma moderated the relation between racist discrimination and sexual and gender minority-specific IPV perpetration: participants with high levels of heterosexist discrimination were at increased risk of sexual and gender minority-specific IPV perpetration than those at the mean. No other interaction effects were detected between racist and heterosexist discrimination, and IPV perpetration |

| Swan et al. (2021) | Discrimination and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration among a convenience sample of LGBT individuals in Latin America | Latin America (Mexico (n = 92), with a minority residing in Ecuador (n = 2), Argentina (n = 1), Colombia (n = 1), Guatemala (n = 1), Paraguay (n = 1), and the Dominican Republic (n = 1)) | N = 99, 39 (F), 51 (M), 5 (Intersex), 1 (transman), 2 (transwomen), 1 (other) | Physical, psychological, sexual IPV, injury | CTS2 | All forms of IPV perpetration and victimization were significantly positively correlated; all forms of IPV were correlated to the other heterosexism subscale, but not with the other dimensions of heterosexism (harassment/rejection; heterosexism at work/school) |

| Taylor and Neppl (2020) | Intimate partner psychological violence among GLBTQ college students: The role of harsh parenting, interparental conflict, and microaggressions | USA | N = 379, 228 (F), 106 (M), 45 (gender minority) | Psychological violence | CTS2 | Experiencing microaggressions was positively associated with IPV perpetration, and this relation was moderated by sexual orientation (i.e., having a bisexual orientation increased the strength of the association between microaggressions and IPV perpetration) |

| Telesco (2003) | Sex role identity and jealousy as correlates of abusive behavior in lesbian relationships | USA | N = 105(F) | Physical and psychological abuse + a total score | The 30 item abusive behavior inventory (ABI) | Dependence was not related to IPV perpetration. Jealousy was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Perceived power imbalances were not associated with IPV perpetration. Gender expression was not associated with IPV perpetration |

| Tognasso et al. (2022) | Romantic attachment, internalized homonegativity and same-sex intimate partner violence perpetration among lesbian women in Italy | Italy | N = 325, 311(F), 2 (transgender women), 12 (other) | Physical, psychological, sexual, and any IPV | CTS2S | Attachment avoidance was positively related to psychological, physical, and any IPV, but not to sexual IPV. The association between Attachment avoidance, and psychological and any IPV was partially mediated by internalized homonegativity. Attachment anxiety was positively related to psychological and any IPV perpetration, but not to physical and sexual IPV. These associations were partially mediated by internalized homonegativity |

| Toro-Alfonso and Rodríguez-Madera (2004) | Sexual coercion in a sample of Puerto Rican gay males | Puerto Rico | N = 302 (M) | Sexual coercion | A questionnaire developed by the authors | Having assertiveness abilities reduced the probability to perpetrate sexual coercion. Sexual victimization in the family of origin was associated with sexual IPV perpetration, while suffering physical and psychological victimization in the family of origin were not. Addictive behaviors were positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Turell et al. (2018) | Disproportionately high: an exploration of intimate partner violence prevalence rates for bisexual people | US |

N = 439, 184 (M), 206 (F), 5 (transwomen), 4 (transmen), 35 (genderqueer/fluid), 5 (Undecided) |

Any IPV (physical and psychological abuse) | ABI | Participants' age and age differences between the partners were not associated with IPV perpetration; partner's age was negatively associated with IPV perpetration. Gender identity was not associated with IPV perpetration. Having a bisexual partner was associated with IPV perpetration. Black/African American and indigenous participants were at increased risk of IPV perpetration. Length of relationship was not associated with IPV perpetration. Having a child was not associated with IPV perpetration. Being in an open relationship and infidelity were both associated with abuse perpetration. Bisexual participants involved in bisexual local or online community were at increased risk of IPV perpetration than those not involved in bisexual communities; however, in the path analysis, involvement in bisexual communities was not directly associated with IPV perpetration. Bi-negativity was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Ummak et al. (2021) | Untangling the relationship between internalized heterosexism and psychological intimate partner violence perpetration: a comparative study of lesbians and bisexual women in Turkey and Denmark | Turkey and Denmark | N = 449, 418 (F), 10 (transgender), 12 (complex) | Psychological IPV | MMEA Scale | Turkish participants were more likely to report all forms of psychological IPV perpetration (restrictive engulfment; denigration; hostile withdrawal; dominance/intimidation) than Danish participants. Bisexual participants were more likely to report all forms of psychological IPV perpetration, except for dominance/intimidation, than Lesbian participants. Internalized heterosexism was positively related to each form of IPV perpetration. Sexual orientation moderated only the relation between internalized heterosexism and dominance/intimidation: among bisexual this relation was not significant. This interactional effect was found both among Turkish and Danish participants. No other moderating effects of sexual orientation or country were detected |

| Waterman et al. (1989) | Sexual coercion in gay and lesbian relationships: predictors and implications for support services | USA | N = 70, 36 (F), 34 (M) | Forced sex; Physical violence |

1 item developed by authors assessing forced sex perpetration; CTS to assess physical violence |

No gender differences in IPV perpetration were found. Physical IPV victimization was associated with physical IPV perpetration, while the association between sexual IPV victimization and perpetration was significant only among men |

| Wei et al. (2020a) |

Multilevel factors associated with perpetration of five types of intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men in China: an ecological model-informed study |

China | N = 578 (M) |

Physical IPV; sexual IPV; monitoring IPV; controlling IPV; emotional IPV; a total score (any IPV) |

IPV-GBM Scale | Bisexual people were at increased risk of IPV perpetration compared to homosexual people. Self-esteem was negatively associated with IPV perpetration; Self-efficacy was negatively associated with emotional IPV perpetration. Perceived instrumental support by family, friends and colleagues was negatively associated with IPV perpetration. Involvement in social activities within the LGB community was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Emotional, controlling, monitoring, sexual, and physical IPV perpetration were all correlated to each other. Drug use during sex was associated with IPV perpetration. An age of 18 or older at sexual debut was positively associated with controlling behaviors and negatively related to emotional IPV. Number of sexual partners was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Perceived stigma was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Wei et al. (2020b) | Effects of emotion regulation and perpetrator- victim roles in intimate partner violence on mental health problems among men who have sex with men in China | China | N = 578 (M) | Physical, sexual, monitoring, controlling, emotional, any IPV | Five items derived from the IPV-GBM Scale | Age, ethnicity, education level, marital status, job, and sexual orientation were not related to IPV perpetration. Age of first homosexual intercourse of 18 or older was negatively associated with physical and psychological perpetration, but not with sexual, monitoring, or controlling IPV. Higher self-esteem was negatively associated only with sexual violence perpetration. Being ever engaged in transactional sex was positively associated only with perpetration of monitoring IPV. Drug use was not related to any form of IPV perpetration. Physical and monitoring, physical and emotional, sexual, and controlling, sexual and emotional, and monitoring and emotional IPV perpetration were positively associated with each other. No other association between the forms of perpetrated IPV emerged. Any IPV perpetration and any IPV victimization were associated with each other |

| Wei et al. (2021) | Prevalence of intimate partner violence and associated factors among men who have sex with men in China | China | N = 431 (M) | Physical, sexual, monitoring, controlling, and emotional IPV | IPV-GBM Scale | Monitoring and any IPV perpetration (not physical, emotional, sexual, and controlling IPV) were positively associated to suicidality. Monitoring, controlling, emotional, and any IPV perpetration (not physical and sexual IPV) were negatively related to general mental health. Emotional and monitoring IPV (not physical, emotional, sexual, and controlling IPV) were positively related to depression |

| Whitton et al. (2019) | Intimate partner violence experiences of sexual and gender minority adolescents and young adults assigned female at birth | USA | N = 352 (F) | Minor psychological IPV, Severe psychological IPV, Minor physical IPV, Severe physical IPV, Injury, Sexual IPV, Coercive control, SGM-specific IPV, Cyber abuse + a total score | The SGM Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (SGM-CTS2); The Coercive Control Scale; the SGM-Specific IPV Tactics Scale; The Cyber Abuse Scale | Age was not associated with IPV perpetration. Participants’ gender identity was not associated with IPV perpetration; participants with a gender minority partner were at increased risk of IPV perpetration than participants with a cisgender partner. Sexual orientation was not associated with IPV perpetration. Black and Latin participants were at increased risk of IPV perpetration |

| Whitton et al. (2021) | Exploring mechanisms of racial disparities in intimate partner violence among sexual and gender minorities assigned female at birth | USA | N = 308 (AFAB SGM) | Minor psychological, severe psychological, physical, and sexual IPV | SGM-CTS2 | Black participants were more likely to report physical, psychological, and sexual IPV perpetration than White participants; Latinx participants were more likely to report more severe psychological, and physical, and sexual IPV perpetration than White participants. No other differences emerged between Black, Latin, and White participants on minor or severe psychological, physical, or sexual IPV perpetration. Child abuse experiences, witnessing violence between parents, and racial discrimination were related to each form of IPV. Economic stress and social support were related to each form of violence except for minor psychological perpetration. Sexual and Gender Minority victimization was positively related only to minor psychological IPV perpetration, while internalized sexual stigma was not related to IPV perpetration. Identifying as Black or Latinx (vs. White) had an indirect effect on severe psychological perpetration via racial discrimination, identifying as Black or Latinx (vs. White) was indirectly associated with minor psychological perpetration through child abuse. Direct effects of race were nonsignificant in these models, except for Black identity in the prediction of severe psychological perpetration and physical perpetration. No other indirect effects of child abuse experiences, witnessing violence between parents, economical stress, racial discrimination, or social support in the association between ethnicity and IPV perpetration |

| Wong et al. (2010) | Harassment, discrimination, violence, and illicit drug use among young men who have sex with men | USA | N = 526(M) | Physical violence | Adaptation of a scale developed by Smith et al. (1995) to measure intimate partner violence among battered women, including 3 items asking about physical violence perpetration | Caucasian participants were more likely to report physical and emotional, but not sexual, IPV perpetration than African American participants. Drug use was related to IPV perpetration |

| Wu et al. (2015) |

The association between substance use and intimate partner violence within Black male same-sex relationships |

USA | N = 74 (M) | Psychological, physical, sexual and injurious IPV | CTS2 | Alcohol use was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Methamphetamine use was associated with IPV perpetration, while marijuana, powered or rock/crack cocaine, or heroin use were not |

| Zavala (2017) | A multi-theoretical framework to explain same-sex intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization: a test of social learning, strain, and self-control | USA | N = 665, 195 (M), 470 (F) | Any IPV | CTS2 | Age was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Non-white participants were at increased risk of IPV perpetration. Depression was positively associated with IPV perpetration. Self-control was negatively associated with IPV perpetration. Social support was not related to IPV perpetration. Anti-gay violence was positively associate with IPV perpetration. Perceived stigma was not associated with IPV perpetration. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with IPV perpetration |

| Zhu et al. (2021) | Moderating effect of self-efficacy on the association of intimate partner violence with risky sexual behaviors among men who have sex with men in China | China | N = 578 (M) | Physical, sexual, monitoring, controlling, emotional, and any IPV | IPV-GBM | Inconsistent condom use with regular partners was positively associated to monitoring and any IPV perpetration, while not to physical, emotional, sexual, and controlling IPV perpetration. Inconsistent condom use with casual partners and multiple regular partners was positively related only to sexual IPV perpetration. Having multiple casual sexual partners was only related to emotional, monitoring, and any IPV perpetration. Self-efficacy moderated the relation between multiple casual sexual partners and emotional IPV perpetration: at high levels of self-efficacy the relation between multiple casual sexual partners and emotional IPV perpetration was no longer significant. No other moderating effect of self-efficacy on the association between risky sexual behaviors and IPV perpetration were found |