Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to compare automated ventilation with closed–loop control of the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) to automated ventilation with manual titrations of the FiO2 with respect to time spent in predefined pulse oximetry (SpO2) zones in pediatric critically ill patients.

Methods

This was a randomized crossover clinical trial comparing Adaptive Support Ventilation (ASV) 1.1 with use of a closed–loop FiO2 system vs. ASV 1.1 with manual FiO2 titrations. The primary endpoint was the percentage of time spent in optimal SpO2 zones. Secondary endpoints included the percentage of time spent in acceptable, suboptimal and unacceptable SpO2 zones, and the total number of FiO2 changes per patient.

Results

We included 30 children with a median age of 21 (11–48) months; 12 (40%) children had pediatric ARDS. The percentage of time spent in optimal SpO2 zones increased with use of the closed–loop FiO2 controller vs. manual oxygen control [96.1 (93.7–98.6) vs. 78.4 (51.3–94.8); P < 0.001]. The percentage of time spent in acceptable, suboptimal and unacceptable zones decreased. Findings were similar with the use of closed-loop FiO2 controller compared to manual titration in patients with ARDS [95.9 (81.6–98.8) vs. 78 (49.5–94.8) %; P = 0.027]. The total number of closed-loop FiO2 changes per patient was 52 (11.8–67), vs. the number of manual changes 1 (0–2), (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

In this randomized crossover trial in pediatric critically ill patients under invasive ventilation with ASV, use of a closed–loop control of FiO2 titration increased the percentage of time spent within in optimal SpO2 zones, and increased the total number of FiO2 changes per patient.

Clinical trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier: NCT04568642.

Keywords: intensive care, pediatric intensive care, mechanical ventilation, Adaptive support ventilation, ASV, closed loop ventilation, automated ventilation, FiO2 controller

Introduction

Critically ill invasively ventilated children frequently need supplementary oxygen, which is provided in humidified warmed air, either via a stand-alone gas blender or via a blender inside the ventilator. Both hypoxemia and hyperoxemia should be adequately responded to, either by increasing or lowering the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), as deteriorations in pulse oximetry (SpO2) readings are associated with worse outcomes, including a higher mortality (1), development of retinopathy, chronic lung disease, and brain injury (2).

The Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC) guidelines suggest targeting “safe” SpO2 targets at the lowest possible FiO2. Obviously, this comes with challenges. First, a too low SpO2 increases the risk of mortality (3). Second, with use of the lowest possible FiO2, children may develop dangerous hypoxemia much easier. Last but not least, maintaining SpO2 in predefined target ranges in critically ill children is difficult due to frequent fluctuations in saturation caused by their respiratory instability. The scarcity of doctors and nurses skilled in titrating FiO2 or inadequate resources to adhere to a tight manual FiO2 regimen exacerbates these issues.

Automated, or closed–loop FiO2 control could prevent hyperoxemia and hypoxemia, incorrect use of oxygen, and reduce the workloads of intensive care unit staff. A recent meta-analysis suggest that use of automated FiO2 titrations are associated with improvement in terms of the time spent in target SpO2 ranges, reduces periods of hyperoxia and severe hypoxia on positive pressure respiratory support in preterm infants (4). It is uncertain whether this the use of closed–loop FiO2 control has similar effects in pediatric patients. Therefore, we evaluated the performance of a closed–loop FiO2 titration system in pediatric patients under Adaptive Support Ventilation. We hypothesized that oxygenation would be safer and more efficient with the use of a closed–loop FiO2 titration system.

Methods

Study design and ethics

This was a single center randomized crossover clinical trial, performed in the Dr. Behcet Uz Children's Research and Training Hospital, Izmir, Turkey. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board, and the study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04568642).

Patient selection

Patients were eligible for participation if: (1) aged between 1 month and 18 years; (2) with an ideal body weight of 7 kg; (3) receiving invasive ventilation with an FiO2 ≥ 25%; and after having received written informed consent from the legal representative. Patients were excluded if hemodynamic instable, or when it was expected that they would not stay stable in the next 5 h, or when there were air leaks around the endotracheal tube ≥40%. Patients could also not participate if the legal representatives had not given written informed consent. We also excluded patients with congenital or acquired hemoglobinopathies affecting SpO2 readings.

Collected data

Demographic data collected using a case report form (CRF) were age (months), gender, height (cm), ideal body weight for the measured height (kg), pediatric index of mortality (PIM) score, admission diagnosis, and lung physiology during the study. Additionally, arterial blood gas (ABG) data were recorded to the CRF.

Breath–by–breath ventilation parameters collected using a MemoryBox (Hamilton Medical AG, Bonaduz, Switzerland) included FiO2 and SpO2, positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP), mean airway pressure (MAP), minute ventilation volume (MinVent), respiratory rate (RR), end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2).

Measurement and calculation

A single-use flow sensor (Hamilton Medical AG, Bonaduz, Switzerland) was placed between the endotracheal tube and the Y-piece (8) to measure the airway pressures and flows, while volume was obtained by integrating the flow signal. CO2 measurements were obtained using a mainstream CO2 sensor (Capnostat5, Philips GmbH, Germany) together with the corresponding adult/pediatric airway adapter that has a dead-space volume of 5 ml (5). Ventilation parameters were measured at each breath. Patients' SpO2 was monitored by means of a Masimo Set sensor attached to their finger (Masimo RD; Masimo Corp., Irvine, CA, USA) to provide the signal used by the closed-loop controller.

Ventilation protocol

Both spontaneously breathing and passive patients were enrolled in the study. They were intubated with an appropriately sized and inflated cuffed tube and ventilated in a semi-recumbent position with a Hamilton-S1 ventilator. If required, patients were sedated and if necessary paralyzed according to the local protocol for sedation and using Comfort behavior scale (6). The IntelliCuff device (Hamilton Medical AG, Bonaduz, Switzerland) was used to target a cuff pressure slightly lower than the patients' peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) level. In auto mode, relative cuff pressure was adjusted 2–5 cm H2O lower than PIP to ensure minimal leak around the ETT with minimal administered cuff pressure. However, according to pediatric ventilation guidelines, the maximum cuff pressure was limited to 20 cm H2O (7). Active humidification with the Hamilton-H900 (Hamilton Medical AG, Bonaduz, Switzerland) was used as required.

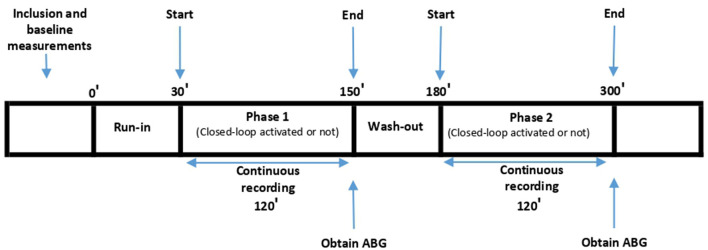

Ventilation was started with standard Adaptive Support Ventilation (ASV) 1.1 settings. ASV 1.1 is a closed-loop ventilation mode in which the clinician first enters the height of the patient to calculate ideal body weight, then determines the percentage of MinVent to be multiplied by the patient's ideal body weight. Then, using the Otis and Mead equations, this MinVent is distributed algorithmically between RR and tidal volume (VT) respecting expiratory time constant (RCexp) of the patient in order to accomplish minimum work of breath and minimum applied pressure. The attending physician subsequently checked the breathing parameters according to the study protocol and wrote them on the CRF while he began collecting data with the MemoryBox in mixed mode. Afterwards, the clinician started the first phase of the study continuing ventilation with standard ASV 1.1 with with only the FiO2 controller activated, the PEEP and minute volume controller deactivated, according to randomization. After 2.5 h of recording in the first phase, the clinician switched the patient to the alternate mode, according to the randomization order. If the patient was ventilated without the FiO2 controller activated in the first phase, the Intellivent FiO2 controller was activated in the second phase. The patient remained in the second phase for 2.5 h as well. The first 0.5 h of the first phase were considered as a run-in phase and the first 0.5 h of the second phase were considered as a wash-out phase. Therefore, the first 0.5 h of each phase were excluded from data analysis. For each patient we collected data for 120 min with the FiO2 controller activated and for 120 min with the FiO2 controller deactivated, and these time periods were compared with regard to the primary and secondary endpoints (Figure 1). The same values for both MinVent and PEEP were maintained during the two phases. Intellivent FiO2 closed-loop controller is a rule based, proportional integral controller described in Supplementary Table 1. Manual titration protocol is described in the same file, too.

Figure 1.

Study Protocol. Run-in: Patient was ventilated with the same mode as Phase 1, excluded from data analysis; Wash-out: Patient was ventilated with the same mode as Phase 2, excluded from data analysis.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was the percentage of time spent in a predefined optimal SpO2 range over the 2-h observation periods. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of time spent in the predefined acceptable, suboptimal, and unacceptable SpO2 ranges, as well as the number of FiO2 adjustments (manual or performed automatically by the closed-loop controller).

Definitions

The definitions for optimal, acceptable, suboptimal, and unacceptable SpO2 ranges are provided in Table 1. We had different predefined cut-offs for the patients at higher and lower PEEP based on PALICC and PEMVEC guidelines (7, 8).

Table 1.

SpO2 (Peripheral oxygen saturation) ranges.

| Group | Unacceptably low | Suboptimally low | Acceptably low | Optimal | Acceptably high | Suboptimally high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower PEEP (<10 cmH2O) | <85% | ≥85 and <90% | ≥90 and <93% | ≥93 and ≤97%; >97% if FiO2 = 0.21 | >97 for ≤ 60 s | >97 for >60 s |

| HigherPEEP (≥10 cmH2O) | <80% | ≥80 and <85% | ≥85 and <88% | ≥88 and ≤92%; >92% if FiO2 = 0.21 | >92 for ≤ 60 s | >92 for >60 s |

PEEP, positive end expiratory pressure; FiO2, Fraction of inspired oxygen.

Power calculation and statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated by means of a pilot study in seven patients. In those seven patients the mean difference between the two phases was 12 ± 19%, median time spent in the optimum range were 86% [55–99 (IQR)] vs. 67% [50–81 (IQR)]. Based on this pilot data, G*Power computed that we needed 30 participants to detect an effect size of Cohen's d = 0.64 with 95% power (α = 0.05, one-tailed) in a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (9). Shapiro-Wilk, skewness and kurtosis normality tests were used to check the distribution of data. Continuous data were expressed in terms of either mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR). We used a paired samples t–test to compare normally distributed data, and the Wilcoxon test when data were not normally distributed. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for the comparison between the percentage of time spent in the target SpO2 range with manual FiO2 control and the percentage with closed-loop FiO2 control, and p-values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant for all comparisons. Statistical testing was carried out with the XLSTAT statistical package (version 2016).

Results

Patients

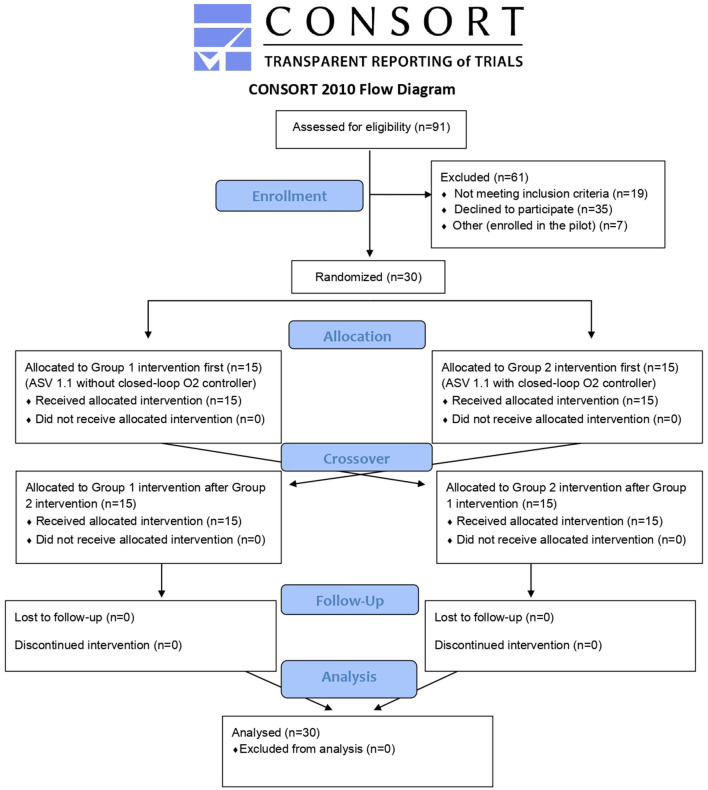

During the period from October 2020 and April 2021, investigators in the PICU of the Dr. Behcet Uz Children's Research and Training Hospital screened a total of 91 intubated and mechanically ventilated patients for inclusion. Of those, 19 were excluded due to meeting at least one of the exclusion criteria and informed consent was not given for a further 35 patients. Of the 37 included patients, the first seven were enrolled for the pilot study and the remaining 30 were enrolled in the present study (Figure 2). Their baseline characteristics, which include their oxygenation index (OI) (10), and pediatric index of mortality 3 (PIM3) scores (11), can be seen in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Consort 2010 flow diagram.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the patients.

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Gender ratio (%f/%m) | 40/60 |

| Age (months) | 21 (11–48) |

| Height (cm) | 93.5 (71.8–111.5) |

| IBW (kg) | 13.5 (8.8–19.8) |

| OI | 3.9 (3–7) |

| PIM3 | 11.9 (5.9–21.2) |

| Admission diagnosis ( n , %) | |

|

Respiratory A.pneumonia A.bronchiolitis LRTI Chylothorax Laryngotracheomalacia |

9, 30 |

|

Neurologic SE Meningoencephalitis |

7, 23 |

|

Renal/Metabolic RTA HUS DKA |

5, 17 |

|

Cardiovascular VSD PDA AS |

3, 10 |

|

HAI CLABSI |

2, 7 |

|

Other Trauma Gastrointestinal surgery |

4, 13 |

| Lung physiology ( n , %) | |

| Restrictive | 10, 33 |

| Mixed | 10, 33 |

| Obstructive | 5, 17 |

| Normal | 5, 17 |

Data are expressed in median and interquartile range (25th−75th) or percentage.

IBW, Ideal body weight; ABW, Actual body weight; OI, Oxygenation index, PIM3, Pediatric index of mortality 3, probability of death; A.pneumonia, Acute pneumonia; A.bronchiolitis, Acute bronchiolitis; LRTI, Lower respiratory tract infection; VSD, Ventricular septal defect; PDA, Patent ductus arteriosus; AS, Aortic stenosis; RTA, Renal tubular acidosis; HUS, Hemolytic uremic syndrome; DKA, Diabetic Keto Acidosis; SE, Status epilepticus; HAI, Healthcare-associated infections; CLABSI, Central line related blood stream infection.

Ten patients had restrictive lung disease, while five had obstructive and a further ten mixed lung disease. Five patients had a normal lung condition. Patient's respiratory mechanics and ventilation variables during the two study phases are shown in Table 3. Also, ABG parameters were presented in Table 4. Seven of the 30 patients met the criteria for mild pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome (PARDS), four for moderate and one for severe PARDS. The way the study was designed meant there was no change to either MinVent or PEEP.

Table 3.

Ventilation parameters during study phases.

| Ventilation variable | ASV + FiO2 controller (n = 30) | ASV + Manual FiO2 (n = 30) | p1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MinVent (l/min) | 2.9 (2.4–3.5) | 2.9 (2.4–3.4) | 0.642 |

| VT/IBW (ml/kg) | 7.5 (6.4–8.1) | 7.4 (6.3–8.4) | 0.19 |

| RR (b/min) | 29.3 (23.1–38.8) | 29.5 (24.3–35.9) | 0.257 |

| PetCO2 (mmHg) | 42 (33.4–50.3) | 42.8 (33.7–54.1) | 0.17 |

| PIP (cmH2O) | 20.2 (14–26.6) | 20 (15.4–25.5) | 0.719 |

| PEEP (cmH2O) | 5 (5–6.5) | 5 (5–6.5) | 1 |

| FiO2 (%) | 31.4 (25.1–44.1) | 36.5 (30–49) | <0.001 |

| FiO2 adjustment (n/2h) | 52 (11.8–67) | 1 (0–2) | <0.001 |

| Ti (s) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.234 |

| Te (s) | 1.3 (0.9–1.7) | 1.4 (0.9- 1.7) | 0.176 |

| SpO2 (%) | 96.2 (95.8–96.8) | 97 (95.2–97.6) | 0.245 |

| SpO2 DOT (%) | 96.4 (93.6–98.7) | 78.4 (51.4–98) | <0.001 |

| OI | 3.1 (2.4–6) | 3.5 (2.6–6.6) | <0.001 |

| S/F | 300.7 (210.8–382.2) | 254.1 (189.2–302.4) | <0.001 |

| TO2 (l/min) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | <0.001 |

Data are expressed in median and interquartile range (25–75th) and compared between ASV+closed loop FiO2 controller and ASV+ Manuel FiO2 titration groups by Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p1).

ASV, Adaptive support ventilation; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; VT, tidal volume expired; IBW, ideal body weight; RR, respiratory rate; PetCO2, end-tidal carbondioxide; PIP, peak inspiratory pressure; Ti, inspiratory time; Te, expiratory time; SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation; SpO2DOT, peripheral oxygen saturation duration in optimal target; OI, oxygenation index; S/F, peripheral oxygen saturation to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio; TO2, therapeutic oxygen use.

Table 4.

ABG parameters.

| ABG variable | ASV + Closed-loop FiO2 (n = 30) | ASV + Manual FiO2 (n = 30) | p1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.36 (7.24–7.44) | 7.36 (7.23–7.43) | 0.13 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 97.5 (89.5–114.5) | 102 (91.8–117) | 0.936 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 38.5 (32.8–48.3) | 38 (32.7–46.5) | 0.873 |

Data are expressed in median and interquartile range (25–75th) and compared between Closed-loop FiO2 and manual FiO2 group by Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p1).

ABG, Arterial blood gas; ASV, Adaptive support ventilation; PaO2, partial oxygen content; PaCO2, partial carbon dioxide content.

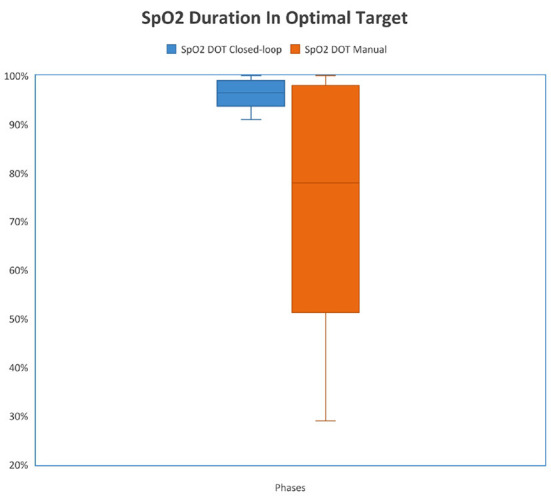

Time spent in optimal SpO2 zones

Patients spent more time in the target SpO2 range when the FiO2 controller was activated. During the study phase with closed-loop FiO2 control, patients spent 96.1% (93.7–98.6 [IQR]) of their time in the optimal range compared to 78.4% [51.3–94.8 (IQR)] of their time in the optimal range when FiO2 was controlled manually (p < 0.001).

Time spent in acceptable, suboptimal, and unacceptable SpO2 zones

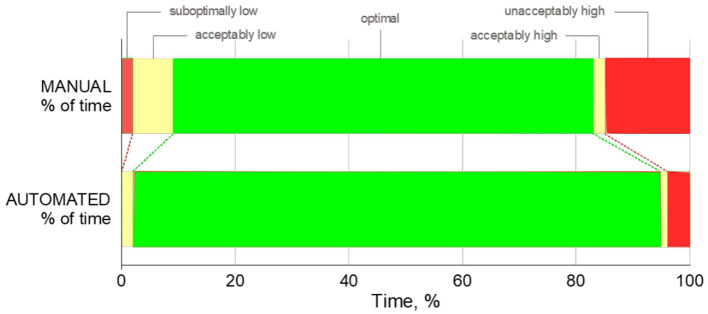

Patients spent less time in the unacceptably low, sub-optimally low, acceptably low, and sub-optimally high zones while the FiO2 controller was activated with p-values 0.032, 0.008, 0.004 and 0.001, respectively. There was no significant difference at the time spent in the acceptably high zone (p = 0.151). A comparison of the percentage of time spent in optimal SpO2 ranges is shown in Figures 3, 4.

Figure 3.

Comparison of duration in optimal target (DOT) SpO2 between study phases. {The median percentage of time spent in the optimal zone was 96.4% [93.6–98.7 (IQR)] when the FiO2 controller was activated and the median percentage of time spent in the optimal zone was 78.4% [51.4–98 (IQR)] when FiO2 was controlled manually (p < 0.001)}.

Figure 4.

Percentage of time spent in unacceptably high/low, acceptably high/low, optimal SpO2 zones. For illustrative purposes, width of each bar represents the mean percentage of time spent.

Number of adjustments made to the FiO2 controller

Another secondary outcome was the number of adjustments made to the FiO2 controller. In the phase of closed-loop FiO2 control, the median number of adjustments was 52 [11.8–67 (IQR)], while the number of FiO2 adjustments during the manual phase was 1 [0–2 (IQR)].

Subgroup analysis

For the normal PEEP group (<10 cm H2O), the median SpO2 in the closed-loop phase was 94.7% [93.6–95.4 (IQR)], whereas the same value for the manual phase was 95.6 % [93.2–96.4 (IQR)] (p = 0.229). For the higher PEEP group (≥10 cm H2O), the median SpO2 in the closed-loop phase was 89.4% [87.6–90.9 (IQR)], whereas the same value for the manual phase was 90 % [88.1–92.1 (IQR)] (p = 0.688). For the closed-loop phase the median OI ratio was 3.1 [2.4–6 (IQR)], the median FiO2 was 31.4% [25.1–44.1 (IQR)], and the median therapeutic O2 usage was 0.3 L/min [0.1–0.7 (IQR)], whereas the same values for the manual phase was 3.5 [2.6–6.6 (IQR)], 36.5% [30–49.1 (IQR)] and 0.5 L/min [0.2–0.9 (IQR)], respectively.

Pediatric ARDS subgroup with closed-loop FiO2 control, patients spent 95.9% [81.6–98.8 (IQR)] of their time in the optimal range compared to 78% [49.5–94.8 (IQR)] of their time in the optimal range when FiO2 was controlled manually. Also, they spent less time in the unacceptably low, sub-optimally low, acceptably low, and sub-optimally high zones while the FiO2 controller was activated, too. In the phase of closed-loop FiO2 control, the median number of adjustments for the PARDS subgroup was 57 [47–69 (IQR)], while the number of FiO2 adjustments during the manual phase was 1 [0–2 (IQR)].

Discussion

In this randomized crossover clinical trial, we compared the percentage of time spent in the target SpO2 range during closed-loop FiO2 control vs. during manual control of FiO2 by the physician in pediatric intensive care patients ventilated in ASV mode. This rule based proportional integral closed-loop FiO2 controller is commercially available since 2011. The groups with a target oxygenation range of 93% to 97% when set PEEP was below 10 cm H2O and 88% to 92% when set PEEP was equal or above 10 cmH2O, may represent the vast majority of mechanically ventilated patients in pediatric intensive care. The median time spent in the target SpO2 range was 96.1% [93.7–98.6 (IQR)] during the closed-loop phase, whereas the same value was 78.4% [51.3–94.8 (IQR)] in the manual phase. This result was consistent with similar studies performed previously in preterm infants (4, 12–16). We can conclude that the automated FiO2 controller performs better and is more effective than manual setting of FiO2 in terms of maintaining patients in the optimal SpO2 range. The median FiO2 in the closed-loop phase was 31.4%, whereas the same value during the manual phase was 36.5% (p < 0.001). The median oxygenation index (OI) in the closed-loop phase was 3.1 [2.4–6 (IQR)], whereas the same value during the manual phase was 3.5 [2.6–6.6 (IQR)]. We also calculated the therapeutic O2 usage, with the median O2 usage being 0.5 L/min [0.2–0.9 (IQR)] in the manual phase, decreasing to 0.3 L/min [0.1–0.7 (IQR)] in the automated phase. This decrease in FiO2 use and OI may represent a more efficient use of therapeutic oxygen. A similar decrease was also noted by Bourassa et al. with their automated FiO2 titration device (17). Considering the surge in demand for mechanical ventilation and the possible scarcity of oxygen gas supply for these patients during pandemics, closed-loop FiO2 control may contribute to a more sparing use of this therapeutic agent (18–20). Friedman et al. aimed to characterize mechanical ventilation patterns in children receiving VV-ECMO and explore whether such practices are correlated to clinical outcomes (21). They found that after adjusting for sickness severity, FiO2 remained the only variable that could be modified. They also found that a 10% rise in FiO2 may be associated for 38% increase of the mortality of aforementioned group (21). The median FiO2 percentage during the automated phase was 31.4 [25.1–44.1 (IQR)], which was less than the median FiO2 during the manual phase at 36.5 [30–49.1 (IQR)]. Based on Friedman's study, it is possible that closed-loop FiO2 control may lower mortality in this population. The median number of manual adjustments required for patients in the manual phase of the study period was 1 [0–2 (IQR)], which means that the clinician may have to change the FiO2 setting at least 12 times per day. Bearing in mind the need during a pandemic for isolation measures and for donning personal protective equipment before entering an isolation room each time an adjustment is made, there may have been too little appreciation of this advantage with a closed-loop system prior to the pandemic.

Due to the small number of patients enrolled in the study, PARDS subgroups cannot be statistically analyzed. Furthermore, the automated FiO2 controller can be used only in ASV mode, which does not allow us to analyze the performance of the oxygen controller in other modes and patients below 7 kg of IBW. However, the ASV 1.1 algorithm was recently found to be safe in pediatric patients in terms of using less driving pressure (22). Another limitation was the unblinded bedside clinicians, who were aware that the closed-loop FiO2 controller was active. More stringent manual titration policy in the control group may have benefited the control group. However, we tried to compare closed- loop FiO2 control vs. standard care applied at the study site. Lastly, 2-h comparisons may not represent the whole course of a real clinical condition; however, due to the need for stable and similar oxygen demand we had to change patients over after 2 h.

Conclusion

In this randomized crossover trial in pediatric patients with different lung conditions, the percentage of time spent in the target SpO2 range in ASV 1.1 with closed-loop FiO2 control was greater compared to the time spent in the target SpO2 zone in ASV 1.1 with manual FiO2 control. The use of closed-loop FiO2 control with ASV 1.1 may therefore contribute to maintaining ventilation in the target range of SpO2 in invasively ventilated pediatric patients.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to an IRB decision which was made in the interest of ensuring patient confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to GC, drgokhanceylan@gmail.com.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board, Dr. Behcet Uz Children's Research and Training Hospital, Izmir, Turkey. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

ES, GC, ST, PH, MC, OS, UK, GA, and HA conceived and designed the study. ES, GC, ST, PH, MC, MS, FS, OS, and UK acquired and analyzed. GC, FS, GA, DN, MS, and HA interpreted the data. GA, GC, and HA did the statistical analysis. ES, GC, DN, MS, and HA drafted the manuscript. OS, GC, ST, PH, MC, ES, UK, and HA had full access to all of the data. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, responsible for the final decision to submit for publication, and have seen and approved the manuscript.

Funding

The participating centers received only material support from Hamilton Medical AG. They received ventilators for the duration of this study.

Conflict of interest

Authors GC, DN, and MS report conflicts of interest, they are both employed by Hamilton Medical AG in the Department of Medical Research. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The handling editor DB declared a past co-authorship with the author MS.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Laubscher for providing data conversion and providing math-lab code to analyze the study data.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.969218/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Stenson B, Brocklehurst P, Tarnow-Mordi W. Increased 36-week survival with high oxygen saturation target in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. (2011) 364:1680–2. 10.1056/NEJMc1101319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn JT, Bancalari E, Snyder ES, Goldberg RN, Feuer W, Cassady J, et al. A cohort study of transcutaneous oxygen tension and the incidence and severity of retinopathy of prematurity. N Engl J Med. (1992) 326:1050–4. 10.1056/NEJM199204163261603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt B, Whyte RK, Asztalos EV, Moddemann D, Poets C, Rabi Y, et al. Effects of targeting higher vs lower arterial oxygen saturations on death or disability in extremely preterm infants: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. (2013) 309:2111–20. 10.1001/jama.2013.5555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitra S, Singh B, El-Naggar W, McMillan DD. Automated versus manual control of inspired oxygen to target oxygen saturation in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinatol. (2018) 38:351–60. 10.1038/s41372-017-0037-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Respironics . Capnostat mainstream CO2 sensor technical specifications [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dijk M, Peters JWB, van Deventer P, Tibboel D. The COMFORT Behavior Scale: A tool for assessing pain and sedation in infants. AJN Am J Nurs. (2005) 105:33–6. 10.1097/00000446-200501000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kneyber MCJ, de Luca D, Calderini E, Jarreau P-H, Javouhey E, Lopez-Herce J, et al. Recommendations for mechanical ventilation of critically ill children from the Paediatric Mechanical Ventilation Consensus Conference (PEMVECC). Intensive Care Med. (2017) 43:1764–80. 10.1007/s00134-017-4920-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Group TPALICC. Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: consensus recommendations from the pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2015) 16:428–39. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. (2007) 39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newth CJL, Stretton M, Deakers TW, Hammer J. Assessment of pulmonary function in the early phase of ARDS in pediatric patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. (1997) 23:169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straney L, Clements A, Parslow RC, Pearson G, Shann F, Alexander J, et al. Paediatric index of mortality 3: an updated model for predicting mortality in pediatric intensive care*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2013) 14:673–81. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31829760cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds PR, Miller TL, Volakis LI, Holland N, Dungan GC, Roehr CC, et al. Randomised cross-over study of automated oxygen control for preterm infants receiving nasal high flow. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2019) 104:F366–f371. 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waitz M, Schmid MB, Fuchs H, Mendler MR, Dreyhaupt J, Hummler HD. Effects of automated adjustment of the inspired oxygen on fluctuations of arterial and regional cerebral tissue oxygenation in preterm infants with frequent desaturations. J Pediatr. (2015) 166:240–244.e241. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lal M, Tin W, Sinha S. Automated control of inspired oxygen in ventilated preterm infants: crossover physiological study. Acta Paediatr. (2015) 104:1084–9. 10.1111/apa.13137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaam AH, Hummler HD, Wilinska M, Swietlinski J, Lal MK, Pas AB. Automated versus manual oxygen control with different saturation targets and modes of respiratory support in preterm infants. J Pediatr. (2015) 167:545–50.e1-2. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claure N, Bancalari E, D'Ugard C, Nelin L, Stein M, Ramanathan R. Multicenter crossover study of automated control of inspired oxygen in ventilated preterm infants. Pediatrics. (2011) 127:e76–83. 10.1542/peds.2010-0939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourassa S, Bouchard P-A, Dauphin M, Lellouche F. Oxygen conservation methods with automated titration. Respir Care. (2020) 65:1433–42. 10.4187/respcare.07240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelissen H, de Grooth H-J, Smulders Y, Wils E-J, de Ruijter W, Vink R, et al. Effect of low-normal vs high-normal oxygenation targets on organ dysfunction in critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2021). 10.1001/jama.2021.13011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bikkina S, Kittu Manda V, Adinarayana Rao UV. Medical oxygen supply during COVID-19: a study with specific reference to state of Andhra Pradesh, India. Mater Today Proc. (2021). 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.01.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra S, Wang L, Ma H, Yiu KCY, Paterson JM, Kim E, et al. Estimated surge in hospital and intensive care admission because of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in the Greater Toronto Area, Canada: a mathematical modelling study. CMAJ Open. (2020) 8:E593–604. 10.9778/cmajo.20200093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman ML, Barbaro RP, Bembea MM, Bridges BC, Chima RS, Kilbaugh TJ, et al. Mechanical ventilation in children on venovenous ECMO. Respir Care. (2020) 65:271–80. 10.4187/respcare.07214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ceylan G, Topal S, Atakul G, Colak M, Soydan E, Sandal O, et al. Randomized crossover trial to compare driving pressures in a closed-loop and a conventional mechanical ventilation mode in pediatric patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. (2021) 56:3035–43. 10.1002/ppul.25561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to an IRB decision which was made in the interest of ensuring patient confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to GC, drgokhanceylan@gmail.com.