Abstract

The functional complementation of two Escherichia coli strains defective in the succinylase pathway of meso-diaminopimelate (meso-DAP) biosynthesis with a Bordetella pertussis gene library resulted in the isolation of a putative dap operon containing three open reading frames (ORFs). In line with the successful complementation of the E. coli dapD and dapE mutants, the deduced amino acid sequences of two ORFs revealed significant sequence similarities with the DapD and DapE proteins of E. coli and many other bacteria which exhibit tetrahydrodipicolinate succinylase and N-succinyl-l,l-DAP desuccinylase activity, respectively. The first ORF within the operon showed significant sequence similarities with transaminases and contains the characteristic pyridoxal-5′-phosphate binding motif. Enzymatic studies revealed that this ORF encodes a protein with N-succinyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferase activity converting N-succinyl-2-amino-6-ketopimelate, the product of the succinylase DapD, to N-succinyl-l,l-DAP, the substrate of the desuccinylase DapE. Therefore, this gene appears to encode the DapC protein of B. pertussis. Apart from the pyridoxal-5′-phosphate binding motif, the DapC protein does not show further amino acid sequence similarities with the only other known enzyme with N-succinyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferase activity, ArgD of E. coli.

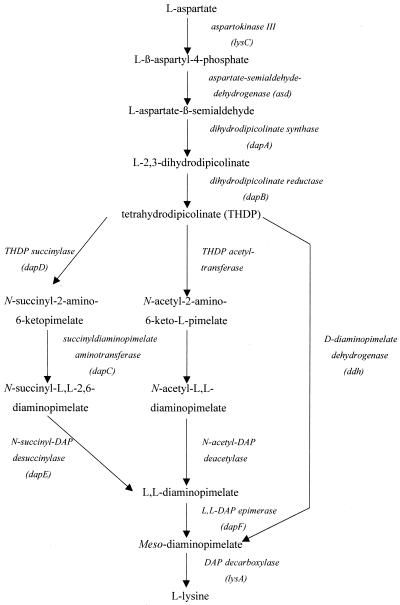

d,l-Diaminopimelate (d,l-DAP) is the direct precursor of l-lysine and moreover an important constituent of the cell wall peptidoglycan of many bacteria (39). There are three alternative pathways in bacteria leading to the synthesis of d,l-DAP (29): (i) the dehydrogenase variant in which the intermediate tetrahydrodipicolinate (THDP) common to all three pathways is converted in a single step to DAP, (ii) the succinylase variant involving two succinylated intermediates, and (iii) the acetylase variant using the acetyl residue instead of succinyl as the blocking group (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

The split pathway for the synthesis of DAP and lysine in prokaryotes. On the left is shown the succinylase branch, and on the right is shown the dehydrogenase branch. The acetylase variant in the middle is comparable to the succinylase variant but uses acetyl groups instead of succinyl groups. The symbols for genes are given below the enzymes.

In the succinylase pathway, THDP is converted by the succinyltransferase (DapD) to N-succinyl-2-amino-6-ketopimelate, which is the substrate of the aminotransferase DapC. Its product, N-succinyl-l,l-DAP, is converted by DapE, a desuccinylase, to the common product of both the succinylase and acetylase pathways, l,l-DAP (27). The acetylase and/or dehydrogenase pathways are found among members of the genus Bacillus (38), while the succinylase pathway is present in Escherichia coli (18). In Corynebacterium glutamicum, both the succinylase and dehydrogenase pathways can operate in d,l-DAP and l-lysine biosynthesis (30). This high variability and flexibility of DAP pathways might ensure the availability of a sufficient amount of meso-DAP for cell wall synthesis under different environmental conditions (37). In addition to the vital role of DAP in the cross-linking of the glycan backbones in the bacterial cell wall and in providing lysine for protein biosynthesis, DAP is a central constituent in the Bordetella pertussis tracheal cytotoxin, which is an important virulence factor that causes several pathological effects in epithelial cells (7, 21).

Since DAP is neither produced nor required by humans, many efforts have been made to study DAP biosynthetic enzymes (8, 24, 28), and DAP analogs are evaluated for their potential to inhibit bacterial growth. Furthermore, the use of DAP auxotrophic mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis BCG, Salmonella subspecies, or Helicobacter pylori as attenuated vaccine strains or for the maintenance of cloning vectors expressing foreign antigens in such attenuated strains has been proposed (9, 17, 23).

Although the biochemistry of the DAP-lysine pathway is very well understood, the genes encoding enzymes involved in this pathway have not been completely characterized. Indeed, only three out of the four genes required for the succinyl pathway of E. coli, dapD, dapE, and dapF, encoding THDP succinylase, N-succinyl-l,l-DAP desuccinylase, and DAP epimerase, respectively, were known (2). Surprisingly, despite the availability of the entire genomic sequence of E. coli and other bacteria, a gene encoding the N-succinyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferase had not been identified in any organism. Only recently, ArgD of E. coli was shown to exhibit both N-acetylornithine and DAP aminotransferase activity, which indicates its participation not only in the arginine but also in the DAP-lysine biosynthesis pathways (20). In the present paper we describe a novel gene locus of B. pertussis containing the dapD and dapE genes as well as a third gene that was characterized as dapC, encoding a novel N-succinyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferase. The identification of this gene will contribute to our understanding of the DAP biosynthesis pathways and possibly to the development of novel antimicrobials targeting these essential anabolic pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (Gibco), and B. pertussis was grown on Bordet-Gengos (BG) agar plates supplemented with 15% sheep blood (3), in Stainer-Scholte broth (33), or in Stainer-Scholte broth with Casamino Acids in place of defined amino acid solutions (13). When appropriate, ampicillin (100 μg/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), gentamicin (10 μg/ml), nalidixic acid (20 μg/ml), DAP (40 μg/ml), or lysine (50 μg/ml) was added. Strains were grown aerobically at 37°C with the exception of E. coli RDE51, which was cultivated at 30°C. The preparation of competent cells, transformations, plasmid preparations, and DNA manipulations were performed according to standard protocols (26).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F−recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) sup44 relA1 λ− φ80dlacZΔM15(lacZYA-argF)U169 | Gibco BRL |

| DH5αMCR | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | 14 |

| RDE51 | araD139 thi Δ(lac)U168 strA dapE::MuCts | 25 |

| AT982 | rel-1 thi-1 dapD4 | 7 |

| AT997 | rel-1 thi-1 dapC15 | 7 |

| SM10 | RP4-2-Tc::Mu thi thr leu suIII Kanr; mobilizing donor strain | 31 |

| B. pertussis | ||

| Tohama I (TI) | Wild type | Rino Rappuoli |

| TIΔdapC | Allelic exchange mutant of TI with a 228-bp deletion in dapC | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript SK | High-copy cloning vector | Stratagene |

| pSS1129 | Bordetella suicide vector | 34 |

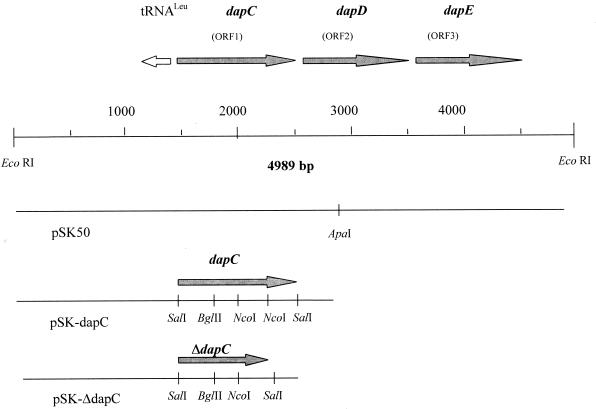

| pSK50 | 5.0-kb EcoRI fragment from TI in pSK including the dap operon of B. pertussis (Fig. 2) | This study |

| pSK-dapC | 2.9-kb ApaI fragment from pSK50 containing dapC and truncated dapD (Fig. 2) | This study |

| pSK-ΔdapC | Derivative of pSK-dapC with a 228-bp NcoI deletion | This study |

| pSS-ΔdapC | EcoRI-BamHI fragment from pSK-ΔdapC joined to pSS1129 | This study |

Complementation of E. coli mutants auxotrophic for DAP biosynthesis.

High-molecular-weight chromosomal DNA of the Tohama I wild-type strain was isolated as described previously (12) and digested with EcoRI. Fragments with an average size of 1 to 8 kb were ligated into the EcoRI-cleaved and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase-dephosphorylated pBluescript SK vector and cloned in E. coli DH5α (Stratagene, San Diego, Calif.). For complementation analyses, two DAP auxotrophic E. coli strains, RDE51 and AT982, lacking functional dapE and dapD loci, respectively, which are able to grow only in the presence of 50 μg of diaminopimelic acid per ml (a mixture of the three DAP isomers; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), were used. Competent cells of the RDE51 and AT982 strains were transformed with the pBluescript SK gene library from B. pertussis and selection was carried out on Luria-Bertani agar containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) but no diaminopimelic acid. Plasmid DNA was isolated from colonies grown overnight or after 2 days of incubation.

Construction of a deletion in the dapC gene.

The plasmid pSK-dapC was digested with NcoI and religated, resulting in a 228-bp in-frame deletion within the dapC gene (pSK-ΔdapC) (see Fig. 2). An EcoRI-BamHI fragment was cloned into the vector pSS1129, resulting in the construct pSS-ΔdapC, which was then transformed in the E. coli strain SM10 (31). Plasmid pSS-ΔdapC was then conjugated into B. pertussis Tohama I, plating the bacteria on BG agar plates containing DAP and lysine. Selection for allelic exchange was carried out as described elsewhere (6, 34). The presence of the deletion in the dapC gene in the respective mutants was verified by Southern blot analysis and by PCR with specific oligonucleotides (26).

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the dapCDE gene locus of B. pertussis. The arrows below the ORFs indicate their transcriptional polarity. Below the dapCDE operon the different subclones used in this study are indicated.

DNA sequence analysis.

DNA fragments derived from B. pertussis and complementing the E. coli dapD and dapE mutants were sequenced using the Applied Biosystems Prism sequencing kit from Perkin-Elmer and the automated sequencer ABI Prism 310. Sequence data for both strands were obtained by subcloning and primer walking. Analysis of the nucleotide sequences was performed using the Genetics Computer Group program package (10). Protein homology searches were conducted in the SwissProt database using the FASTA and TFASTA programs and in the Prosite database using the MOTIFS program and were further elaborated using the PILEUP program.

Determination of transaminase activity.

E. coli was grown on minimal medium consisting of (per liter) 7 g of KH2PO4, 3 g of K2HPO4, 1 g of (NH4)2SO4, 246 mg of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 1 mg of CaCl2 · 2H2O, 0.5 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O, 0.5 mg of MnSO4 · 4H2O, 0.5 mg of ZnSO4 · H2O, 0.1 mg of CuSO4 · 5H2O, 0.05 mg of thiamine, and 5.5 g of glucose · H2O. Cells were harvested after overnight incubation at 37°C, washed with 0.9% NaCl, resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and disrupted with a microtip-equipped sonifier. The homogenate was centrifuged for 20 min at 20,000 × g, and the resulting extract was applied to a PD-10 column (Amersham-Pharmacia). Determination of the N-acyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferase activity (EC 2.6.1.17) was based on the succinyl-DAP (or acetyl-DAP-)-dependent formation of glutamate from α-ketoglutarate. The assay system consisted of 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.25 mM pyridoxal-5′-phosphate, 4 mM α-ketoglutarate, 8 mM acyl-2,6-DAP, 1 mM EDTA, and gel-filtered extract. Assay mixtures were incubated at 37°C. Samples (30 μl) were taken at different time intervals, and reactions were stopped by addition of 30 μl of stop reagent (0.75 M HClO4 in 7 M ethanol), neutralized with 20 μl of neutralizing solution (0.1 M K2CO3, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]), and used for glutamate quantification. This was done by automated precolumn derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde, followed by separation by reversed phase chromatography (LC ChemStation HP 1900) with fluorometric detection (15). Protein concentration was determined after precipitation of the protein (1). All experiments were carried out at least three times.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the 5.0-kb EcoRI fragment containing the dapCDE genes of B. pertussis has been deposited in the EMBL data bank under accession number AJ009834.

RESULTS

Cloning and characterization of the dap locus of B. pertussis.

A partial gene bank from B. pertussis Tohama I DNA digested with EcoRI was established in the high-copy-number vector pBluescript SK and was used to identify six plasmids conferring a stable DAP prototrophy to the E. coli dapE mutant RDE51. All six plasmids contained a 5.0-kb EcoRI fragment (pSK50) that was also able to complement the E. coli dapD mutant AT982, which is blocked in the succinylase step of DAP biosynthesis (Fig. 1). The successful complementation of both E. coli strains, RDE51 and AT982, indicated a close linkage of the dapD and dapE genes in B. pertussis.

The complete nucleotide sequence of the 5.0-kb EcoRI fragment of pSK50 was determined using a primer walking strategy. The DNA fragment contains three open reading frames (ORFs) consisting of 1,191, 819, and 1,137 bp, encoding putative proteins of 397, 273, and 379 amino acids (Fig. 2), respectively. A tRNA gene coding for the rare tRNALeuW was found immediately upstream of the start codon of ORF1. In all three ORFs only one codon specific for this tRNA is present, located in ORF1 at nucleotide position 58 to 60 (see Fig. 4). ORFs 1 and 2 are separated by 26 nucleotides. ORF2 and ORF3 overlap by one codon, indicating translational coupling of the two genes, suggesting that the three ORFs are organized in an operon.

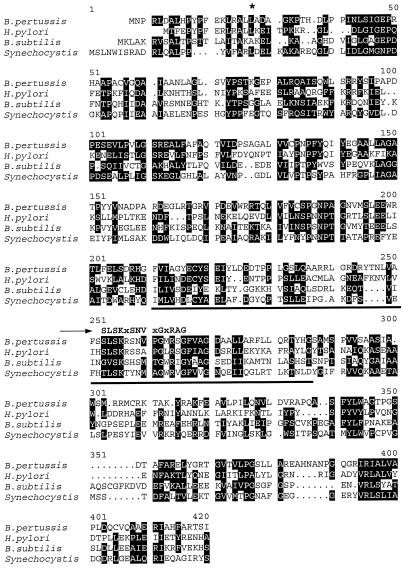

FIG. 4.

Sequence homologies between DapC and several putative aminotransferases. Shown is a multiple sequence alignment of DapC from B. pertussis and the product of three ORFs from H. pylori (36) (HP0624), B. subtilis (GenBank accession number P53001), and Synechocystis sp. (GenBank accession number D64000). Amino acids identical or similar in at least three positions are shaded. Groups of similar amino acids are as given in the legend to Fig. 3. The arrow indicates the consensus sequence of the pyridoxal-5′-phosphate binding site common to several aminotransferases. The active site lysyl residue that binds pyridoxal phosphate through Schiff base linkage is found within this consensus sequence at position 256. The bar below the sequence marks 76 amino acids which were deleted in pSK-ΔdapC. The only specific codon for the rare tRNALeuW encoded by a gene immediately upstream of ORF1 is marked by an asterisk.

Search for sequence similarities of the putative ORFs.

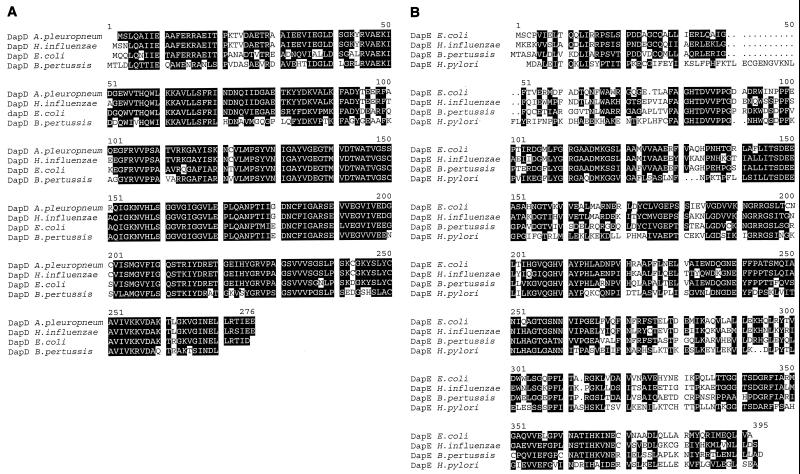

The 5.0-kb EcoRI fragment derived from B. pertussis complements auxotrophic E. coli mutants with defective dapD and dapE genes on media lacking DAP. Indeed, the growth characteristics of the complemented mutants are very similar to that of the E. coli wild-type strain (data not shown). Consequently, comparison of the amino acid sequences revealed high similarities between the putative protein encoded by ORF2 and the DapD proteins from E. coli (25), Haemophilus influenzae (11), and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (19) and between the protein deduced from the DNA sequence of ORF3 and the DapE proteins from E. coli (4), H. influenzae (11), and H. pylori (36). Similarities shown in Fig. 3 range from 79 to 82% (DapD) and from 58 to 77% (DapE). These data demonstrate that ORF2 and ORF3 do indeed code for the Bordetella counterparts of the THDP succinylase DapD and the N-succinyl-l,l-DAP desuccinylase DapE, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Sequence homologies between the DapD and DapE proteins of several bacteria. Shown are multiple sequence alignments of DapD of A. pleuropneumoniae (GenBank accession number P41396), H. influenzae (GenBank accession number P45284), and E. coli (GenBank accession number K02970) to the product of ORF2 (DapD B. pertussis) (A) and of DapE of E. coli (GenBank accession number X57403), H. influenzae (GenBank accession number P444514), and H. pylori (36) (HP0212) (B) to the product of ORF3 (DapE B. pertussis). Amino acids identical or similar in at least three proteins are shaded. Groups of similar amino acids are as follows: D, E, Q, and N; A, S, G, P, and T; F, Y, and W; K, H, and R; V, L, I, and M; and C.

ORF1 encodes a hypothetical protein with an overall amino acid similarity of about 40% to several putative proteins from H. pylori (36), Bacillus subtilis (32), Synechocystis sp. (16) and other bacteria (Fig. 4). The motif search revealed that the amino acid sequences of ORF1 and the homologous proteins contain a pyridoxal-5′-phosphate attachment site (Fig. 4), which is a characteristic feature of transaminases (35). Accordingly, at least one of the proteins with significant sequence similarities to B. pertussis ORF1, AspB from B. subtilis, was shown to exhibit aminotransferase activity (32).

Characterization of ORF1 and elucidation of its function as a transaminase involved in DAP biosynthesis.

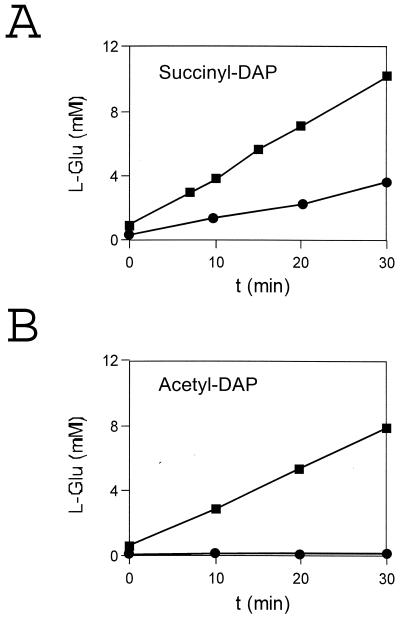

The sequence analysis and the close linkage of ORF1 to the THDP succinylase- and N-succinyl-l,l-DAP desuccinylase-encoding genes dapD and dapE suggested that it might encode the N-succinyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferase converting the product of the succinylase to the substrate of the desuccinylase. We therefore functionally characterized the gene product of ORF1 by directly assaying for transaminase activity. For this purpose, the E. coli strain DH5αMCR was transformed with pSK50 containing the 5.0-kb EcoRI fragment with the entire operon consisting of ORF1, dapD, and dapE, with plasmid pSK-dapC, a derivative of pSK50 containing only ORF1 and a truncated dapD, or, as controls, with plasmid pSK-ΔdapC or the vector alone (Fig. 2). When the extracts of the two control strains were incubated with succinyl-DAP and α-ketoglutarate, formation of l-glutamate was obtained only due to the chromosomally encoded transaminase activity of E. coli (Fig. 5A). However, when the extract of E. coli pSK50 or pSK-dapC was used in the enzyme assay, a significant increase in succinyl-DAP-dependent l-glutamate accumulation was observed (Fig. 5A). Based on the amount of protein present in the respective assay of recombinant E. coli strains, the following specific activities (in micromoles minute−1 milligram of protein−1) were determined by subtracting the basal activity and by calculation of the amount of protein present in the assay: with pSK50, 0.014 ± 0.006, and with pSK-dapC, 0.013 ± 0.005. Therefore, ORF1 exhibits transaminase activity and was accordingly designated dapC. In addition to succinyl-DAP, acetyl-DAP was also applied as a substrate for the transaminase, since the various bacteria analyzed so far possess succinyl-DAP- or acetyl-DAP-specific enzyme activities when assayed in crude extracts (30, 38). Using acetyl-DAP as an alternative substrate, a significant activity with extracts of E. coli pSK50 and pSK-dapC was detected (Fig. 5B), whereas extracts of E. coli pSK and pSK-ΔdapC showed almost no transaminase activity. The specific activity for extracts of E. coli pSK50 or pSK-dapC with acetyl-DAP as the substrate was calculated (see above) to be 0.0047 ± 0.001 μmol min−1 mg of protein−1. The low background activity is consistent with the inability of the E. coli enzyme to use acetyl-DAP as a substrate when assayed in extracts.

FIG. 5.

Transaminase activity in crude extracts of E. coli strains harboring plasmids containing different parts of the B. pertussis dapCDE locus, as quantified by l-glutamate accumulation, with either pSK50 (■) or pSK (●) and N-succinyl-l,l-DAP as substrate (A) or with either pSK-dapC (■) or pSK (●) and N-acetyl-l,l-DAP as substrate (B). The protein amount in the respective assay was 37 μg with pSK50 and 22 μg with pSK (Fig. 5A) and 114 μg with pSK50 and 44 μg with pSK (Fig. 5B), respectively.

Characterization of a B. pertussis dapC mutant.

To further substantiate the participation of ORF1 in the DAP-lysine biosynthesis pathway, we tried to introduce by allelic exchange the dapC allele containing the deletion of its pyridoxal phosphate binding motif into the chromosome of B. pertussis. However, despite the addition of DAP and lysine to the selection medium, after several independent attempts we were able to identify only a single mutant out of several hundred clones screened that carried the deletion within the dapC gene (data not shown). The only obvious phenotype of this mutant was a significantly reduced generation time compared with that of the wild type (7.05 ± 0.60 h versus 5.57 ± 0.30 h). The addition of DAP or lysine to the medium had no obvious effect and did not influence the generation time of this mutant.

DISCUSSION

The investigation of a chromosomal locus of B. pertussis able to complement E. coli dapD and dapE mutants led to the identification of a new gene, dapC. Due to the close linkage of these three genes they appear to constitute an operon with dapC being the first gene in the order of transcription. The dapD and dapE genes encode enzymes with THDP succinylase and N-succinyl-l,l-DAP desuccinylase activity, respectively, and their amino acid sequences show extensive similarities with their E. coli counterparts (Fig. 3). The dapC gene codes for a protein sharing significant sequence similarities with several aminotransferases. The presence of the dapC gene within the putative DAP operon prompted us to investigate its possible involvement in DAP biosynthesis. In fact, a transaminase is required to convert the product of DapD, N-succinyl-2-amino-6-ketopimelate, to the substrate of DapE, N-succinyl-l,l-2,6-DAP. Accordingly, transaminase activity could be detected in crude lysates of an E. coli strain transformed with the B. pertussis dapC gene using N-succinyl-DAP as a substrate. Interestingly, N-acetyl-DAP was also accepted as a substrate, although with about half of the activity observed for N-succinyl-DAP. We conclude that dapC encodes the transaminase involved in DAP biosynthesis of B. pertussis and that its most likely substrate in vivo is N-succinyl-l,l-DAP.

In early experiments with extracts of E. coli, Weinberger and Gilvarg (38) demonstrated a quite strict requirement of the E. coli N-succinyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferase, which accepted N-succinyl-l,l-DAP but not N-succinyl-meso-DAP as a substrate. More recently, similar experiments using the purified enzyme contradicted these findings and showed that the purified E. coli transaminase accepted compounds with rather large structural alterations at the position of the succinyl group (8). These data are in agreement with our results regarding the substrate specificity of the B. pertussis enzyme. In fact, many transaminases are known to exhibit quite relaxed substrate specificities (30). The apparently much less pronounced sequence conservation among DapC homologs of different bacteria as compared to the strong sequence conservation of DapD or DapE proteins of different organisms (Fig. 3 and 4) could represent the structural counterpart of this characteristic feature.

In the literature confusion still exists regarding the gene symbol-enzyme relationships of the dapC and dapD genes (22), and in several database annotations dapD genes are still incorrectly reported to encode the N-succinyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferases instead of the THDP succinylases (2). Moreover, in none of the bacterial genomes sequenced so far could a candidate gene encoding a DAP-specific aminotransferase be identified (20). In this respect, it is worth mentioning that the B. pertussis dapCDE locus was not able to functionally complement the only available E. coli strain (AT997) (data not shown) that was isolated as a dapC mutant (5) but later did not prove to have a clear phenotype. In fact, it was impossible to reconcile the originally reported map position of the mutation and the genome sequence of E. coli.

A major breakthrough in our understanding of these puzzling findings was recently achieved in a study which shows that in E. coli the argD-encoded N-acetylornithine aminotransferase also exhibits N-succinyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferase activity and appears to be engaged in both pathways (20). This finding is of particular importance because it may provide an explanation for the unusual difficulties we experienced with the genetic inactivation of the dapC gene of B. pertussis. Assuming that the dapC gene product is participating in additional biosynthetic pathways, its deletion may require suppressor mutations in other aminotransferases, which generally show quite low substrate specificities, to supply the lost function(s). In fact, the only dapC mutant of B. pertussis that was obtained exhibits a general growth defect which appears to be independent of the presence of DAP or lysine in the culture medium. The involvement of the B. pertussis DapC protein in additional pathways will be the subject of future investigations.

It is interesting that, apart from the pyridoxal-5′-phosphate binding motif, the DapC protein of B. pertussis and ArgD of E. coli do not show further amino acid sequence similarities, and accordingly, BLAST searches with DapC in the E. coli genome sequence or vice versa with ArgD in the B. pertussis genome sequence resulted in the alignment with several other putative aminotransferases with high significance values, but not with each other (data not shown). The identification of ArgD of E. coli and of DapC of B. pertussis as enzymes with N-succinyl-l,l-DAP aminotransferase activities finally solves a long-lasting debate and closes an important gap in our knowledge about this crucial biosynthetic pathway specific to eubacteria. Moreover, the involvement of proteins with entirely different primary structures in identical biosynthetic steps poses interesting evolutionary questions and has important consequences for the design of antimicrobial drugs directed against such enzymes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Degussa AG for the synthesis of succinyl-DAP and acetyl-DAP, Klaus Hantke (Tübingen) for the DAP auxotroph E. coli mutants, and Carol Gibbs and Dagmar Beier for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to T.M.F., by grant SFB479/A2 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, and by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie to R.G.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bensadoun A, Weinstein D. Assay of proteins in the presence of interfering materials. Anal Biochem. 1976;70:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(76)80064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berlyn M K B. Linkage map of Escherichia coli E-12, edition 10: the traditional map. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:814–984. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.814-984.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordet J, Gengou O. L'endotoxine coquelucheuse. Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 1909;23:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouvier J, Richaud C, Higgins W, Bogler C, Stragier P. Cloning, characterization, and expression of the dapE gene of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5265–5271. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5265-5271.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukhari A I, Taylor A L. Genetic analysis of diaminopimelic acid- and lysine-requiring mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1971;105:844–854. doi: 10.1128/jb.105.3.844-854.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbonetti N H, Khelef N, Guiso N, Gross R. A phase variant of Bordetella pertussis with a mutation in a new locus involved in the regulation of pertussis toxin and adenylate cyclase toxin expression. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6679–6688. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6679-6688.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cookson B T, Hwei-Ling C, Herwaldt L A, Goldman W E. Biological activities and chemical composition of purified tracheal cytotoxin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2223–2229. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.2223-2229.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox R J, Sherwin W A, Lam L K P, Vederas J C. Synthesis and evaluation of novel substrates and inhibitors of N-succinyl-L,L-diaminopimelate aminotransferase (DAP-AT) from Escherichia coli. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7449–7460. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtiss R, III, Nakayama K, Kelley S M. Recombinant avirulent Salmonella vaccine strains with stable maintenance and high level expression of cloned genes in vivo. Immunol Investig. 1989;18:583–596. doi: 10.3109/08820138909112265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchs T M, Deppisch H, Scarlato V, Gross R. A new gene locus of Bordetella pertussis defines a novel family of prokaryotic transcriptional accessory proteins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4445–4452. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4445-4452.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldner M, Jakus C M, Rhodes H K, Wilson R J. The amino acid utilization by phase I Bordetella pertussis in a chemically defined medium. J Gen Microbiol. 1966;44:439–444. doi: 10.1099/00221287-44-3-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant S G, Jessee J, Bloom F R, Hanahan D. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4645–4649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones B N, Gilligan J P. ο-Phthaldialdehyde precolumn derivatization and reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography of polypeptide hydrolysates and physiological fluids. J Chromatogr. 1983;266:471–482. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)90918-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneko T, Tanaka A, Sato S, Kotani H, Sazuka T, Miyajima N, Sugiura M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. I. Sequence features in the 1 MB region from map position 64% to 92% of the genome. DNA Res. 1995;2:153–166. doi: 10.1093/dnares/2.4.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karita M, Etterbeek M L, Forsyth M H, Tummuru M K R, Blaser M J. Characterization of Helicobacter pylori dapE and construction of a conditionally lethal dapE mutant. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4158–4164. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4158-4164.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kindler S H, Gilvarg C. N-succinyl-L-α,ɛ-diaminopimelic acid deacylase. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:3532–3535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lalonde G, O'Hanley P D, Stocker B A, Denich K. Characterization of a 3-dihydroquinase gene from Actinobacter pleuropneumoniae with homology to the eukaryotic genes qa-2 and QUTE. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ledwidge R, Blanchard J S. The dual biosynthetic capability of N-acetylornithine aminotransferase in arginine and lysine biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3019–3024. doi: 10.1021/bi982574a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luker K E, Tyler A N, Marshall G R, Goldman W E. Tracheal cytotoxin structural requirements for respiratory epithelial damage in pertussis. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:733–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patte J-C. Biosynthesis of threonine and lysine. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 528–541. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavelka M S, Jr, Weisbrod T R, Jacobs W R., Jr Cloning of the dapB gene, encoding dihydrodipicolinate reductase, from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2777–2782. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2777-2782.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterkofsky B, Gilvarg C. N-succinyl-L-diaminopimelic-glutamic transaminase. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:1432–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richaud C, Richaud F V, Martin C, Haziza C, Patte J-C. Regulation of expression and nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli dapD gene. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:14824–14828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scapin G, Blanchard J S. Enzymology of bacterial lysine biosynthesis. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1998;72:279–324. doi: 10.1002/9780470123188.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scapin G, Reddy S G, Blanchard J S. Three-dimensional structure of meso-diaminopimelic acid dehydrogenase from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13540–13551. doi: 10.1021/bi961628i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scapin G, Cirilli M, Reddy S G, Gao Y, Vederas J C, Blanchard J S. Substrate and inhibitor binding sites in Corynebacterium glutamicum diaminopimelate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3278–3285. doi: 10.1021/bi9727949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrumpf B, Schwarzer A, Kalinowski J, Pühler A, Eggeling L, Sahm H. A functionally split pathway for lysine synthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4510–4516. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4510-4516.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorokin A, Azevedo V, Zumstein E, Galleron N, Ehrlich S D, Serror P. Sequence analysis of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome region between the serA and kdg loci cloned in a yeast artificial chromosome. Microbiology. 1996;142:2005–2016. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stainer D W, Scholte M J. A simple chemically defined medium for the production of phase I Bordetella pertussis. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;63:7501–7510. doi: 10.1099/00221287-63-2-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stibitz S, Yang M S. Subcellular localization and immunological detection of proteins encoded by the vir locus of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1991;174:4288–4296. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4288-4296.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sung M-H, Tanizawa K, Tanaka H, Kuramitsu S, Kagamiyama H, Hirotsu K, Okamoto A, Higuchi T, Soda K. Thermostable aspartate aminotransferases from a thermophilic Bacillus species. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2567–2572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomb J F, White O, Kerlavage A R, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wehrmann A, Phillip B, Sahm H, Eggeling L. Different modes of diaminopimelate synthesis and their role in cell wall integrity: a study with Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3159–3165. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3159-3165.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinberger S, Gilvarg C. Bacterial distribution of the use of succinyl and acetyl blocking groups in diaminopimelic acid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1970;101:323–324. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.1.323-324.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Work E. A new naturally occurring amino acid. Nature. 1950;165:74–75. doi: 10.1038/165074b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]