Abstract

RNA fingerprinting by arbitrarily primed PCR was used to isolate Sinorhizobium meliloti genes regulated during the symbiotic interaction with alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Sixteen partial cDNAs were isolated whose corresponding genes were differentially expressed between symbiotic and free-living conditions. Thirteen sequences corresponded to genes up-regulated during symbiosis, whereas three were instead repressed during establishment of the symbiotic interaction. Seven cDNAs corresponded to known or predicted nif and fix genes. Four presented high sequence similarity with genes not yet identified in S. meliloti, including genes encoding a component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, a cell surface protein component, a copper transporter, and an argininosuccinate lyase. Finally, five cDNAs did not exhibit any similarity with sequences present in databases. A detailed expression analysis of the nine non-nif-fix genes provided evidence for an unexpected variety of regulatory patterns, most of which have not been described so far.

Rhizobia are taxonomically diverse members of the α subdivision of the proteobacteria that induce the formation of specialized organs, called nodules, on the roots of leguminous plants. During nodule formation, bacteria invade the plant cells and differentiate into nitrogen-fixing bacteroids that export fixed nitrogen into the plant cells. Nodules provide the endosymbiotic bacteria with a microenvironment suitable for nitrogen (N2) fixation, including a very low ambient O2 concentration compatible with nitrogenase activity. Many plant and bacterial genes contribute to the development of a nitrogen-fixing nodule, only a few of which are known. The best-characterized bacterial symbiotic genes include those involved in nitrogenase synthesis and activity (the nif and fixABCX genes) and two operons involved in the synthesis of a respiratory oxidase with high affinity for oxygen (fixNOQP and fixGHIS). Remarkably, these two sets of genes belong to the same regulon, coordinated by the FixLJ two-component regulatory system (7). FixL is an oxygen-sensitive sensor histidine kinase that phosphorylates the FixJ transcription regulator in response to the dramatic drop in oxygen concentration that takes place inside the nodule. Phosphorylated FixJ activates the transcription of two intermediary regulatory genes, nifA and fixK, that control expression of the nif and fixNOQP genes, respectively.

We reasoned that bacterial genes whose expression is differentially regulated in nodules as compared to under free-living conditions could be of special relevance for the symbiotic interaction. With the aim of identifying such genes, we employed the RNA fingerprinting by arbitrarily primed PCR (RAP) technique (30), a method closely related to the differential display technique, which has been widely used in eukaryotes. RAP uses an arbitrary primer at a low annealing temperature for synthesizing the first strand of cDNA by reverse transcription (16), thus accommodating the lack of polyadenylation of bacterial RNAs. In this work, we compared the RNA fingerprints of bacterial cells in the nitrogen-fixing symbiotic state (bacteroids) to those of free-living cells grown under oxic or microoxic conditions in rich medium.

This work has led to the identification of a set of Sinorhizobium meliloti genes whose expression is either positively or negatively regulated during symbiosis. Sequence analysis of the corresponding expressed sequence tags (ESTs) pointed to new functions that could be important for the establishment of the symbiotic interaction. Furthermore, a detailed expression analysis of nine genes by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR showed the existence of a variety of regulatory patterns, most of which have not been described so far.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbiological material and techniques.

All S. meliloti strains used in this study were isogenic with GMI211 (lac Smr) (7). GMI5601 (lac nifAZ239::Tn5) and GMI5704 (lac fixJ2.3::Tn5) were constructed by David et al. (7). GMI942 was constructed by Foussard et al. (12). S. meliloti strains were grown at 30°C in TY complex medium (25) or in defined M9 medium (17) supplemented with 0.3 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, and 2 μM biotin. Sterilized carbon sources were added at 20 mM final concentration. Microoxic conditions were achieved either as described by de Philip et al. (8) (2% oxygen for 4 h) or using the stoppered-tube assay (STA) described by Ditta et al. (9) (<1% oxygen for 16 h).

Medicago sativa cv. Gemini seedlings were aseptically grown on agar slants made with nitrogen-free Fahraeus medium. Three-day-old plants were inoculated with the different S. meliloti strains. Nodules (0.25 g) were harvested and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen 3 weeks after inoculation or 2 weeks after inoculation where Fix− strains were involved. Nodules were ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle, and the powder was suspended in 2 ml of 50 mM Tris-hydrochloride (pH 7.6)–500 mM mannitol. Debris were sedimented by centrifugation for 5 min at 800 × g. Bacteroids were pelleted by centrifugation of the supernatant for 5 min at 12,000 × g, and stored at −80°C if necessary.

RNA preparation.

The bacterial pellet from a 25-ml culture (optical density at 600 nm = 0.5) or from 0.25 g of nodules was resuspended and incubated for 10 min at 65°C in 2 ml of prewarmed lysis solution (1.4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 4 mM EDTA, 75 μg of proteinase K). Proteins were precipitated by adding 1 ml of NaCl (5 M) at 4°C. Nucleic acids were precipitated from the supernatant by addition of 1 volume of isopropanol, and the pellet was resuspended in nuclease-free water. DNA was eliminated by the addition of 7.5 U of fast protein liquid chromatography-purified RNase-free DNase I (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England). RNAs were further extracted with 1 vol of a 24:24:1 mix of phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol and 1 vol of a 24:1 mix of chloroform-isoamylalcohol and then precipitated with 90% ethanol. The RNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in nuclease-free water. RNAs were quantitated by measuring the absorbancy at 260 nm. Absence of contaminating DNA in the preparation was ensured by PCR amplification, with each specific primer pair.

RAP.

The arbitrary primers used originated from an Arabidopsis thaliana primer library. They were 10 to 18 nucleotides in length, with a mean GC content of 50%.

First-strand cDNA synthesis took place in a 16.5-μl reaction volume. One microliter of total bacterial RNA (50 ng), 7.1 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated H2O, and 1 μl (50 ng) of an arbitrary primer were heated at 70°C for 10 min and quickly chilled on ice. After brief centrifugation, 3.4 μl of the following 5× buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2), 2 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol (DTT) and 1 μl of a 25 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix were added and incubated at 42°C for 2 min. After addition of 1 μl (200 U) of SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) and thorough mixing by pipetting up and down, the reaction tube was incubated for 50 min at 42°C. Reverse transcriptase was inactivated by heating at 95°C for 5 min as we observed that heating at 70°C did not fully inactivate the enzyme.

For PCR amplification, 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.4], 500 mM KCl), 1 μl of 50 mM MgCl2, 1 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix (25 mM), 1 μl of reverse primer (50 ng), 1 μl of sense primer (50 ng), 0.2 μl of [α-33P]dCTP (10 μCi/μl; 2,000 Ci/mmol), and 0.5 μl (2.5 U) of Taq DNA polymerase were added to the first-strand synthesis reaction mix. After gentle mixing, the reaction mixture was layered with 1 drop of silicone oil and submitted to a first, low-stringency, PCR cycle (94°C for 5 min, 40°C for 5 min, and 72°C for 5 min) and then 30 high-stringency cycles (94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min) and 1 cycle at 72°C for 10 min. Two microliters of 80% formamide with bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol dyes was added to 2.5 μl of each PCR sample. The samples were heated to 95°C for 3 min and electrophoresed on a standard acrylamide-urea sequencing gel. After autoradiography, the RAP products of interest were eluted from the polyacrylamide sequencing gel by incubating the gel band in Tris-HCl (10 mM)-EDTA (0.1 mM) solution at 65°C for 2 h. After centrifugation, 50 μl of eluate was reamplified by PCR using the primers and the stringent PCR conditions described above, omitting the radioisotope. Products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel, and bands of the correct size were extracted from the agarose gel with the Jetsorb kit (Genomed, Beverly Hills, Calif.). The products were directly cloned into the pGEMT vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.), or blunt-ended and cloned by standard methods (26) into an EcoRV digested pBluescript II vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.).

RT-PCR expression analyses.

Sequence data from fixN, nifH, hemA, and from each differentially expressed RAP product were used to design specific primers. Primer sequences are available at http://www.toulouse.inra.fr/lbmrpm/eng/hp_jb.htm. The reactions were performed as described above for the RAP procedure, except that (i) Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase was used, (ii) radioisotope was omitted, and (iii) the first low-stringency PCR cycle was omitted and replaced by 94°C for 3 min. RT-PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel, blotted onto a nylon membrane (Biodyne A Transfer membrane; Pall, East Hills, N.Y.) and probed with a 32P-labeled DNA probe, generated by PCR using the same set of primers. Washing of membranes was carried out in 0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 42°C for 30 min.

DNA sequence analysis.

Clones were sequenced using an ABI PRISM Dye terminator cycle-sequencing ready reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer, Oak Brook, Ill.) on an ABI 373 automated sequencer (ABI, Columbia, Md.). Database searches were conducted through the National Center for Biotechnology Information Web page using the BLAST2 package program (1). The sequences were aligned using the Multalin program and the modified blosum62 table (5). Homologous domain searches were conducted using the ProDom database (6).

RESULTS

ESTs detection by RAP.

The RAP technique (30) uses arbitrary-primed RT of RNA molecules followed by PCR (RT-PCR) to highlight differences in the composition of two different RNA populations. Briefly, a first strand of cDNA is made by RT of a subset of RNA molecules using an arbitrary primer hybridizing under poorly stringent conditions. The second cDNA strand is synthesized from a second arbitrary primer at low stringency in the presence of Taq polymerase. The resulting cDNA products are then amplified by PCR using the same pair of primers, at high stringency with simultaneous radiolabeling. The PCR products are separated by polyacrylamide-urea gel electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography. The cDNAs of interest can then be eluted from the gel and cloned for further analysis. The original RAP technique was slightly modified here in order to achieve RT, second-strand synthesis, and PCR amplification in one tube and to minimize the amount of RNA material needed (see Materials and Methods for details). The arbitrary primers used originated from an A. thaliana primer library that was available in the laboratory. Primers were 10 to 18 nucleotides in length, with a mean GC content of 50%.

The RAP procedure was applied to total RNAs extracted from S. meliloti bacteria grown in rich medium under oxic, mild (2% oxygen), or severe (<1% oxygen) microoxic conditions and from symbiotic bacteroids isolated from nodules 3 weeks after inoculation of alfalfa. Different control reactions were performed: (i) a reaction without RNA to eliminate bands due to primer self-amplification, (ii) a reaction without reverse transcriptase to detect DNA contamination of the RNA preparations, and (iii) a reaction on RNAs isolated from plant roots, to identify bands due to plant RNA contamination of the bacteroid preparation. RAP reactions were performed at least two times independently to ensure that the fingerprints were reproducible.

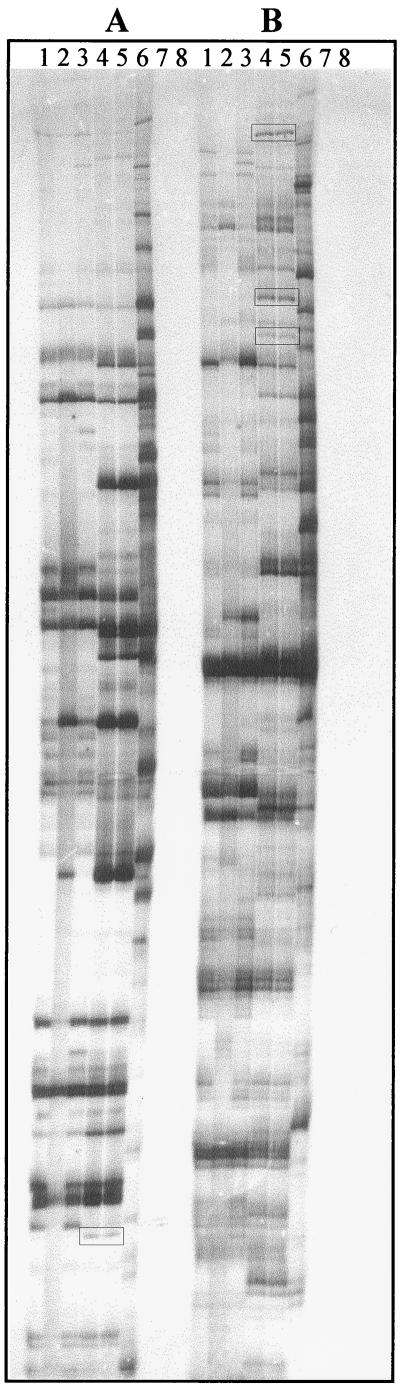

In total, 50 different pairs of primers were tested that gave rise to 32 bands reproducibly enhanced in symbiotic bacteroids (see examples in Fig. 1). These differential bands were sliced out of the gel, and the corresponding cDNA molecules were eluted. The released DNA molecules were reamplified by PCR using the same pair of arbitrary primers as originally used, and the products were either directly cloned into the pGEMT vector (Promega), or blunt ended and cloned into an EcoRV-digested pBluescript II vector (Stratagene).

FIG. 1.

S. meliloti RNA fingerprints obtained by RAP. Examples of RNA fingerprints obtained using two different primer pairs (A and B) are shown. RT-PCRs were performed on RNAs isolated from free-living oxic bacteria (lane 1), bacteria subjected to microoxic conditions (2% O2) (lane 2), and bacteria subjected to severe microoxic conditions (<1% O2) (lane 3). Lanes 4 and 5, 3-week-old bacteroids; lane 6, Medicago roots; lane 7, RT-PCR without RNA; lane 8, PCR on symbiotic RNAs (no RT step). Products differentially enhanced in symbiotic bacteroids are boxed.

In differential display techniques, contaminant cDNA species are often reamplified together with the cDNA of interest from the eluted material. A restriction-enzyme fingerprinting approach (27) was thus performed for rapid assessment of the diversity of cloned cDNA species using two tetra-nucleotide recognition site enzymes, MspI and Sau3A. Clones with the same restriction pattern should be identical, and the largest class should correspond to the gene of interest. However, we observed that, in many cases, there was no predominating cDNA class, and thus several clones presenting different restriction patterns were selected for further analysis.

ESTs sequence analysis.

Out of 90 ESTs clones sequenced, 72 were unique. Forty-nine of them were rejected as they corresponded to bacterial rRNAs or plant RNAs.

Of the 23 remaining clones, 4 corresponded to already-known S. meliloti nifB, nifH, fixB, and fixC genes. In addition, three of the clones were predicted to encode proteins homologous to Nif proteins from other rhizobium species (Table 1). We identified these genes as the likely nifD, nifE, and nifK orthologues of S. meliloti. nifHDKE and fixABCX expression in S. meliloti strain 2011 was indeed known from previous work (29) to be specifically induced under symbiotic conditions as compared to free-living microoxic conditions (see also Discussion).

TABLE 1.

Sequence similarities between predicted RAP translation products and proteins in databases

| Product | Size (amino acids) | Most similar sequence(s) (accession no.) | % Identity | % Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAP3 | 74 | PDH, Z. mobilis (Y12884) | 47 | 65 |

| RAP5 | 33 | ARGH, H. influenzae (P44314) | 66 | 78 |

| RAP6 | 90 | WAPA, B. subtilis (Q07833) | 34 | 49 |

| RAP6 | 90 | RHSD, E. coli (P16919) | 29 | 49 |

| RAP8 | 160 | COPB, X. campestris (B36868) | 36 | 50 |

| RAP8 | 160 | PCOB, E. coli (S52254) | 31 | 49 |

| RAP17 | 42 | NifB, S. meliloti (P09824) | 100 | |

| RAP18 | 50 | NifD, Rhizobium sp. (M26961) | 75 | 81 |

| RAP19 | 61 | NifE, Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 (P55673) | 86 | 91 |

| RAP20 | 45 | NifH, S. meliloti (V01215) | 100 | |

| RAP21 | 38 | NifK, Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 (P19067) | 98 | 98 |

| RAP22 | 50 | FixB, S. meliloti (P09819) | 100 | |

| RAP23 | 63 | FixC, S. meliloti (P09820) | 100 |

Sequence analysis of the other 16 RAP cDNAs (97 to 505 bp in size) revealed that 4 of them putatively encode proteins with homology to proteins present in databases (Table 1). The remaining clones did not show any sequence similarity to known sequences. The bacterial origin of all these cDNAs was ensured by hybridizing Southern blots of S. meliloti genomic DNA with each cloned cDNA as a probe (data not shown).

RAP3 showed similarity with the E1p component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex from the α-proteobacteria Zymomonas mobilis and Rickettsia prowazekii and from mitochondria. The PDH complex consists of three enzymes: PDH (E1p), dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase (E2p), and lipoamide dehydrogenase (E3) (22). The prediction that RAP3 encoded the E1p component of the complex was validated by further sequence analysis (3). The PDH complex catalyzes the synthesis of acetyl coenzyme A and has indeed been postulated to be a key enzyme of carbon metabolism in bacteroids.

The RAP5 protein showed limited but very high sequence similarity (66% identity over 33 amino acids) with argininosuccinate lyases from Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli, and Z. mobilis (AAD19417). Argininosuccinate lyase, encoded by the argH gene in E. coli, contributes to the last step of arginine biosynthesis. No other potential homologs to RAP5 besides argininosuccinate lyases were detected using the BLASTX 2.0.10 program (Expect = 1). Hence we identified RAP5 as the possible argH orthologue.

RAP6 is predicted to encode a protein with similarity to the wall-associated protein WAPA from Bacillus subtilis (Q07833) (11) and to the Rhs proteins from E. coli (14) (Table 1). The sequence similarity was observed within a domain (domain PD004656 [ProDom release 99.2]) only detected so far in WAPA and Rhs proteins. These proteins have been proposed to be ligand-binding proteins at the surface of the bacterial cell.

The RAP8 translation product showed similarity with CopB of Xanthomonas campestris and Pseudomonas syringae and with PcoB of E. coli (Table 1). The sequence similarity was observed on a relatively large portion of the protein (160 amino acids) and specifically with CopB of X. campestris and P. syringae (P12375) and PcoB of E. coli. Again, the region of similarity lies within a domain (domain PD024328 [ProDom release 99.2]) that is unique to these proteins. The cop operon from P. syringae encodes two periplasmic proteins, CopA and CopC; an outer membrane protein, CopB; and a probable inner membrane protein, CopD. Together, these proteins contribute to copper resistance in sequestering and compartmentalizing copper in the periplasm and outer membrane (4, 18).

Expression analysis of the RAP genes by RT-PCR.

Detailed expression analysis of the RAP genes, except those corresponding to nif and fix genes, was performed by RT-PCR on different total RNA preparations. Using specific primers designed from the DNA sequence of the different clones, RT-PCR products were obtained and subjected to Southern hybridization. Specific radiolabeled probes were generated by PCR amplification of the corresponding clones. As a control, the constitutively expressed S. meliloti hemA gene (2) was in the same way subjected to the RT-PCR procedure using hemA-specific primers. No RT-PCR product was detected in reaction mixture controls that contained no reverse transcriptase, thus excluding a contamination of the RNA preparations by DNA. RT-PCRs were performed at least two times independently to assess reproducibility.

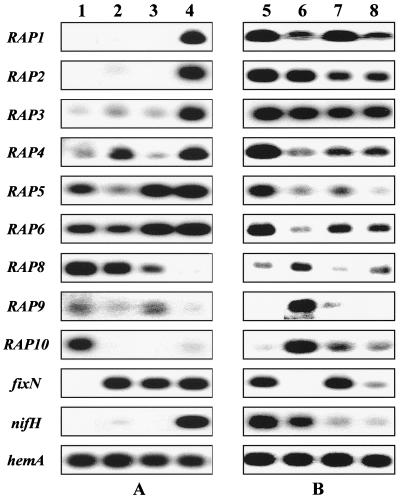

To validate the RT-PCR procedure under our experimental conditions, the expression profiles of the nifH and fixN genes were determined by this technique. nifH and fixN are two S. meliloti symbiotic genes whose regulation of expression has been characterized in detail using gene fusions. nifH and fixN expression is regulated by the nifA and fixK genes, respectively, in response to low oxygen signalling mediated by the FixLJ system (7). Results obtained by RT-PCR (Fig. 2) were in full accordance with previous data. Expression of fixN was indeed detected under both microoxic and symbiotic conditions (Fig. 2A), whereas nifH expression was almost exclusively detected under symbiotic conditions, as reported before (26).

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR expression analysis of selected RAP products. All reactions were performed under stringent conditions using specific primers (see Materials and Methods for experimental details). (A) Autoradiographs of RT-PCRs on RNAs isolated from free-living oxic bacteria (lane 1), bacteria subjected to microoxic conditions (2% O2) (lane 2), and bacteria submitted to severe microoxic conditions (<1% O2). Lanes 1 to 3, growth in TY rich medium; lane 4, 3-week-old bacteroids. hemA, control. (B) Expression patterns of RAP genes in nifA, fixK, and fixJ regulatory mutants of S. meliloti. RT-PCRs were performed on RNAs isolated from symbiotic bacteroids 2 weeks after inoculation of alfalfa with the wild-type strain (GMI 211) (lane 5), a fixK mutant (GMI 942) (lane 6), a nifA mutant (GMI 5601) (lane 7), and a fixJ mutant (GMI 5704) (lane 8).

Seven ESTs (RAP7, -11, -12, -13, -14, -15, and -16) appeared to be constitutively expressed according to the RT-PCR assay (data not shown) and thus might be false positives of the RAP screening procedure.

Three ESTs, RAP1, -2, and -3, corresponded to genes almost exclusively expressed under symbiotic conditions (Fig. 2A). Clearly, expression of these genes is not solely mediated by oxygen limitation. In order to test the possible effect of the carbon source on their expression, RT-PCRs were performed on S. meliloti RNAs isolated from free-living cells grown in M9 minimal medium containing either mannitol or succinate as the sole carbon source. RAP1, -2, and -3 genes showed no or very weak expression in these media, much like cells grown in TY rich medium (data not shown). In further work (3), we have found that RAP3 expression can be induced upon free-living conditions by the addition of pyruvate to the culture medium. By contrast, pyruvate had no effect on RAP1 and RAP2 expression (data not shown).

RAP4, RAP5, and RAP6 corresponded to genes expressed under both symbiotic conditions and at least one of the microoxic conditions tested. RAP5 and RAP6 were expressed to levels similar to that detected in nodules when pure cultures were subjected to the STA that reproduces the scarce oxygen environment of the nodule (9). RAP4 had a more complex pattern of regulation since it was expressed under mild but not severe microoxic conditions.

Lastly, three ESTs (RAP8 to -10) corresponded to genes whose expression was repressed in symbiosis. These three ESTs clearly corresponded to false positives of our initial screening procedure (see Discussion). They were nevertheless retained for further analysis, as they clearly pointed to regulatory events operating inside the nodule. RAP8 and RAP10 were partially repressed in the absence of oxygen, thus suggesting that their expression is under oxygen control.

In summary, in addition to seven nif and fix genes whose expression was known before this work to be induced under symbiotic conditions, six ESTs were isolated that were indeed preferentially expressed in bacteroids and three were fortuitously isolated that were instead down-regulated in symbiosis. (The nucleotide sequences of these 16 RAP products are available at http://www.toulouse.inra.fr/lbmrpm/eng/hp_jb.htm.)

Expression analysis of the symbiotically regulated genes in nif and fix mutants of S. meliloti.

To test whether expression of the newly isolated genes was controlled by the fixLJ, fixK, nifA regulatory pathway, RT-PCRs were performed on RNAs isolated from selected mutants of S. meliloti. RNAs were extracted from bacteroids of the wild type (GMI211), fixK (GMI942), nifA (GMI5601), and fixJ (GMI5704) S. meliloti strains (Fig. 2B). Because non-nitrogen-fixing nodules senesce rapidly, RNAs were extracted from mutant and wild-type bacteroids only 2 weeks after inoculation of alfalfa.

RT-PCRs showed that fixN expression depended both on fixJ and fixK, whereas nifH expression was abolished in both a fixJ and a nifA mutant (Fig. 2B). These data are fully consistent with those described before, using gene fusions (6, 26).

No effect of the fixJ, fixK, and nifA mutations was detected on RAP3 symbiotic expression. RAP3 is thus a clear example of a gene whose expression is induced in bacteroids independently of oxygen and of the fixLJ regulatory cascade and whose expression does not depend on the nitrogen fixation status of the nodule. RAP1 and RAP2 genes showed reduced expression in a fixJ mutant (Fig. 2B). In addition, RAP1 expression was reduced in a fixK mutant, whereas RAP2 expression was reduced in a nifA mutant. These results suggest a positive, albeit partial, control of RAP1 and RAP2 expression by fixK and nifA, respectively.

By contrast, expression of RAP4, -5, and -6 was markedly decreased in all three nif and fix mutants tested. We hypothesized that this could be a consequence of the Fix− status of these nodules. Further support for this hypothesis came from the observation that RAP4 symbiotic expression was also greatly decreased in a nifH mutant (data not shown). This feature thus clearly distinguishes RAP4, -5, and -6 from the known nif and fix genes whose expression is not affected by the Fix− status of the nodule (see nifH and fixN in Fig. 2B).

The RAP8, RAP9, and RAP10 genes were clearly derepressed in the fixK mutant, thus suggesting their symbiotic repression is mediated by the FixK transcriptional regulator.

DISCUSSION

Detection of differential transcription by RAP.

Genetics is the method of choice for identifying bacterial genes involved in complex, symbiotic or pathogenic, interactions. Because some of these genes can be essential for free-living bacteria and because not all of them display a clear phenotype upon inactivation, molecular techniques are also of interest. As far as the rhizobium-legume symbiosis is concerned, the in vivo expression technology strategy, originally developed in plant and animal pathogens (21), has been recently used to identify bacterial genes expressed within the nodule (20). Also, a transcriptional survey of the recently sequenced 500-kb symbiotic plasmid of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 (13) was performed by reverse-Northern blotting (23). Here we report on another approach, based on the RAP molecular technology (30) in an effort to identify new bacterial genes regulated during symbiosis. The use of both the in vivo expression technology and RAP approaches is based on the hypothesis that genes specifically expressed in bacteroids could be of special importance for establishment of the symbiosis. The RAP approach allowed us to isolate 13 ESTs corresponding to S. meliloti genes activated in bacteroids. Seven of these 13 ESTs corresponded to known or predicted nif and fix genes of S. meliloti, including nifB, nifD, nifE, nifH, nifK, fixB, and fixC. These genes are under the control of the NifA transcriptional activator. It is known from previous work that expression of a nifH-lacZ fusion, although it depends on the fixLJ-nifA regulatory cascade, cannot be obtained under free-living microoxic conditions in strain 2011, which we used in this work (28). The reason for this lack of nifH expression in pure culture is not completely clear. We previously proposed that NifA synthesis or activity could be limiting under nonsymbiotic conditions in strain 2011 (28, 29). In the present work, we have confirmed using RT-PCR that nifH expression was indeed restricted to nodules (Fig. 2A). Thus, isolation of nifA-dependent genes in the course of the RAP screening procedure is consistent with the literature.

We observed a high proportion of contaminants and false positives in our screening, many of which were of ribosomal origin, as already described (19). We also isolated sequences of plant origin probably because abundant plant mRNAs copurified with bacteroids.

Three products were isolated that corresponded to genes actually repressed under symbiotic conditions, i.e., that had a pattern of expression opposite to what we expected. The likely reason that explains isolation of these sequences is the following. As described above, a band that appears differential on a gel (Fig. 1) actually consists of several molecular species, of which relative abundance may vary. We suspect that the RAP8, -9, and -10 sequences were isolated, for they corresponded to poorly abundant but readily clonable contaminant species. Nevertheless, these genes were retained for further analysis as their characterization might reveal genetic and physiological regulations operating during symbiosis. In addition, it is known in other rhizobia that turning some genes off, such as nod genes in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae, is essential for normal establishment of the symbiotic interaction (15). Thus, the characterization of these repressed genes is of interest as it could shed light on critical changes occurring during bacteroid differentiation.

New symbiotically regulated S. meliloti genes.

Identification of orthologues from limited sequence data is of course difficult. The forthcoming availability of the complete sequence of the genome of S. meliloti (http://sequence.toulouse.inra.fr/meliloti.html) will help solve this problem. However, the high similarity observed over the full length of the RAP sequences suggests that the predictions we have made in this work are reasonably safe. For example, further sequence analysis of RAP3 indeed confirmed that it encodes the α-subunit of the PDH complex of S. meliloti (3). It has been proposed that PDH contributes, together with malic enzymes, to the synthesis of acetyl coenzyme A from malate and succinate, which are the restricted carbon sources of bacteroids (10).

Although limited in length, the similarity observed between the RAP5 product and the ArgH proteins is very high, thus suggesting that RAP5 encodes argininosuccinate lyase, the last enzyme of the arginine biosynthetic pathway.

The predicted RAP6 product shared similarity with WAPA from B. subtilis (11) and Rhs components from E. coli (14). Wall-associated proteins of gram-positive bacteria are involved in cell wall metabolism, secretion, adhesion, and other cell surface-associated functions. However the precise function of WAPA is still obscure. The Rhs elements are complex sequences, assembled from several discrete components, found in the chromosomes of many natural E. coli strains. The biological function of these elements has not been established, but it was proposed that the Rhs core proteins are binding proteins of the cell surface and provide the cell with an advantage in a specific habitat, such as a eukaryotic host or the soil or water environment (14). The presence of such proteins at the surface of bacteroids could be important for interaction with the host cell.

Among the sequences repressed in bacteroids, the RAP8 product showed similarity with CopB of X. campestris and P. syringae and the E. coli pcoB operon, which are implicated in copper transport. Copper is of special importance for the rhizobium-legume symbiosis, since bacteroids synthesize a copper-containing cbb3 oxidase that allows them to cope with the very low oxygen concentration of the nodule. A specific transport system has been identified in B. japonicum and S. meliloti that uses a P-type ATPase, FixI, to transport copper inside the bacteroids (24). RAP8 repression associated with fixGHIS expression in symbiotic conditions thus may reflect an adaptation of copper metabolism in bacteroids.

Regulation of the new S. meliloti genes.

Symbiotic expression of nine RAP genes was investigated in the known regulatory mutants, fixJ, fixK, and nifA by RT-PCR. As a control, the profile of expression of nifH and fixN, two S. meliloti symbiotic genes whose expression has been studied in great detail with gene fusions, was determined in the RT-PCR assay. Data obtained using these two techniques were in full agreement, thus validating the RT-PCR procedure. The RT-PCR assay, however, should be considered only as a semiquantitative assay under our experimental conditions. Nevertheless, we are confident that major and reproducibly observed changes reported here are indeed meaningful.

Most of the selected RAP genes exhibited original profiles of expression. As for RAP1 and RAP2, RAP3 expression is induced in the symbiotic stage as compared to that under free-living conditions. Symbiotic expression of RAP3 did not depend on the fixLJK-nifA regulatory pathway. Moreover, we have found recently that expression of the corresponding pdhA gene is not triggered in minimal M9 medium using either mannitol or succinate as a carbon source (3). Instead high expression of pdhA (RAP3) was observed in the presence of pyruvate, likely acting as a coinducer (3). Although RAP1, -2, and -3 all displayed initially the same pattern of expression (Fig. 2A), several lines of evidence indicate that RAP1 and RAP2 are under a different genetic control than RAP3. First, RAP1 and RAP2 expression is not influenced by pyruvate. Second, whereas RAP3 expression is completely independent of the fixLJ regulatory operon, both RAP1 and RAP2 expression was partly but reproducibly weakened in a fixJ background. Moreover, RAP1 expression was lowered in a fixK background as compared to the wild type but was unaffected by a nifA mutation. Conversely, RAP2 expression was weakened in a nifA background and unaffected in a fixK mutation. This suggests that RAP1 and RAP2 might be under fixK and nifA control, respectively.

fixK clearly acts also as a repressor. In the case of RAP8, RAP9, and RAP10, whose expression is repressed in bacteroids, strong derepression was observed in a fixK mutant. Thus, fixK represses directly or indirectly expression of these genes. However, for RAP9 and -10, no significant derepression was observed in a fixJ mutant in spite of the fact that fixJ positively regulates fixK expression (2). One possibility to rationalize this observation would be that fixJ positively regulates RAP9 and RAP10 expression. Such a situation has been already reported for nifA and fixK, which are indeed both under positive control by fixJ and negative control by fixK.

Finally, RAP4, -5, and -6 clearly differed from known nif and fix genes since their symbiotic expression was reduced in Fix− mutants, including a nifH mutant in the case of RAP4. We thus propose that symbiotic expression of these genes depends not only on oxygen but also on the nitrogen fixation status of the nodule.

Detailed studies are now required to assess the validity of the hypotheses made above and to clarify the underlying genetic pathways. The present work is highly complementary to the S. meliloti genome sequencing project which is under way. Knowledge of the complete genome sequence will help in characterizing further the genes described here. Inversely, the present work will contribute to functional genetics as it will point to regions of the genome which might be of special relevance for symbiosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. Labeur and L. Mène-Saffrane for their contribution to this work, L. Sauviac for automatic cycle sequencing, and J. Gouzy for expert help in sequence analysis. J. V. Cullimore and F. Ampe are gratefully acknowledged for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the European Union in the frame of the BIOTECH programme (FIXNET, BIOT4-CT97-2319). D.C. was supported by a doctoral fellowship from the French Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche and by the FIXNET program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batut J, Daveran-Mingot M L, David M, Jacobs J, Garnerone A M, Kahn D. fixK, a gene homologous with fnr and crp from Escherichia coli, regulates nitrogen fixation genes both positively and negatively in Rhizobium meliloti. EMBO J. 1989;8:1279–1286. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabanes, D., P. Boistard, and J. Batut. Symbiotic induction of pyruvate dehydrogenase genes from Sinorhizobium meliloti. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Cooksey D A. Copper uptake and resistance in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corpet F, Gouzy J, Kahn D. Recent improvements of the ProDom database of protein domain families. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:263–267. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David M, Daveran M L, Batut J, Dedieu A, Domergue O, Ghai J, Hertig C, Boistard P, Kahn D. Cascade regulation of nif gene expression in Rhizobium meliloti. Cell. 1988;54:671–683. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Philip P, Batut J, Boistard P. Rhizobium meliloti Fix L is an oxygen sensor and regulates R. meliloti nifA and fixK genes differently in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4255–4262. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4255-4262.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ditta G, Virts E, Palomares A, Kim C H. The nifA gene of Rhizobium meliloti is oxygen regulated. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3217–3223. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.3217-3223.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driscoll B T, Finan T M. NAD(+)-dependent malic enzyme of Rhizobium meliloti is required for symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:865–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster S J. Molecular analysis of three major wall-associated proteins of Bacillus subtilis 168: evidence for processing of the product of a gene encoding a 258 kDa precursor two-domain ligand-binding protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:299–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foussard M, Garnerone A M, Ni F, Soupene E, Boistard P, Batut J. Negative autoregulation of the Rhizobium meliloti fixK gene is indirect and requires a newly identified regulator, FixT. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:27–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4501814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freiberg C, Fellay R, Bairoch A, Broughton W J, Rosenthal A, Perret X. Molecular basis of symbiosis between Rhizobium and legumes. Nature. 1997;387:394–401. doi: 10.1038/387394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill C W, Sandt C H, Vlazny D A. Rhs elements of Escherichia coli: a family of genetic composites each encoding a large mosaic protein. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:865–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight C D, Rossen L, Robertson J G, Wells B, Downie J A. Nodulation inhibition by Rhizobium leguminosarum multicopy nodABC genes and analysis of early stages of plant infection. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:552–558. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.552-558.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang P, Pardee A B. Differential display of eukaryotic messenger RNA by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Science. 1992;257:967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1354393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills S D, Jasalavich C A, Cooksey D A. A two-component regulatory system required for copper-inducible expression of the copper resistance operon of Pseudomonas syringae. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1656–1664. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1656-1664.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagel A, Fleming J T, Sayler G S. Reduction of false positives in prokaryotic mRNA differential display. BioTechniques. 1999;26:641–643. doi: 10.2144/99264bm11. , 648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oke V, Long S R. Bacterial genes induced within the nodule during the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:837–849. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osbourn A E, Barber C E, Daniels M J. Identification of plant-induced genes of the bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pathovar campestris using a promoter-probe plasmid. EMBO J. 1987;6:23–28. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel M S, Roche T E. Molecular biology and biochemistry of pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes. FASEB J. 1990;4:3224–3233. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.14.2227213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perret X, Freiberg C, Rosenthal A, Broughton W J, Fellay R. High-resolution transcriptional analysis of the symbiotic plasmid of Rhizobium sp. NGR234. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:415–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preisig O, Zufferey R, Hennecke H. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum fixGHIS genes are required for the formation of the high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:297–305. doi: 10.1007/s002030050330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg C, Boistard P, Denarie J, Casse-Delbart F. Genes controlling early and late functions in symbiosis are located on a megaplasmid in Rhizobium meliloti. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;184:326–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00272926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoham N G, Arad T, Rosin-Abersfeld R, Mashiah P, Gazit A, Yaniv A. Differential display assay and analysis. BioTechniques. 1996;20:182–184. doi: 10.2144/96202bm04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soupene E. Régulation symbiotique de l'expression de gènes impliqués dans la fixation de l'azote lors de l'interaction Rhizobium meliloti- Medicago sativa: rôle de l'oxygène. This. Toulouse, France: Université Paul Sabatier; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soupene E, Foussard M, Boistard P, Truchet G, Batut J. Oxygen as a key developmental regulator of Rhizobium meliloti N2- fixation gene expression within the alfalfa root nodule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3759–3763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welsh J, Chada K, Dalal S S, Cheng R, Ralph D, McClelland M. Arbitrarily primed PCR fingerprinting of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4965–4970. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]