Abstract

BACKGROUND

Incidence of gallstones in those aged ≥ 80 years is as high as 38%-53%. The decision-making process to select those oldest old patients who could benefit from cholecystectomy is challenging.

AIM

To assess the risk of morbidity of the “oldest-old” patients treated with cholecystectomy in order to provide useful data that could help surgeons in the decision-making process leading to surgery in this population.

METHODS

A retrospective study was conducted between 2010 and 2019. Perioperative variables were collected and compared between patients who had postoperative complications. A model was created and tested to predict severe postoperative morbidity.

RESULTS

The 269 patients were included in the study (193 complicated). The 9.7% of complications were grade 3 or 4 according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. Bilirubin levels were lower in patients who did not have any postoperative complications. American Society of Anesthesiologists scale 4 patients, performing a choledocholithotomy and bilirubin levels were associated with Clavien-Dindo > 2 complications (P < 0.001). The decision curve analysis showed that the proposed model had a higher net benefit than the treating all/none options between threshold probabilities of 11% and 32% of developing a severe complication.

CONCLUSION

Patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists scale 4, higher level of bilirubin and need of choledocholithotomy are at the highest risk of a severely complicated postoperative course. Alternative endoscopic or percutaneous treatments should be considered in this subgroup of octogenarians.

Keywords: Cholecystitis, Gallstones, Choledocholithotomy, Elderly, Post-operative complications

Core Tip: The incidence of gallstone disease is high in octogenarian patients. There are no contraindications in performing cholecystectomy in this population, however, they may be at higher risk of complications. Herein, we will analyze perioperative variables to understand their impact on postoperative courses. Then, we will construct a model in order to help in the selection of patients aged > 80 years who need cholecystectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Extended life expectancy, coupled with the increased incidence of gallstones with aging, progressively leads to more elderly patients being evaluated for possible surgery for symptomatic gallstones[1,2].

The incidence of gallstones in those aged 80 or over is as high as 38%-53%, and it could increase up to 80% for patients over 90 years of age[3-5]. After an initial episode of biliary colic, 20%-40% of patients will experience recurrent episodes[6,7]. Within one year, 14% of patients will develop acute cholecystitis, 5% biliary acute pancreatitis (BAP) and 5% choledocholithiasis[8,9]. Acute Cholecystitis (AC) is the sixth most common gastrointestinal disease encountered in the emergency department and the second most common cause of hospital admission in the United States[10].

With the aid of modern perioperative care and laparoscopic surgery, patients between 65 and 80 years of age are now thought to have operative risks comparable to the younger population[5]. To date, the outcomes regarding the safety of cholecystectomy performed in older patients are controversial[11-13].

Age itself is one of the critical factors influencing mortality and morbidity after cholecystectomy[14,15]. The greater burden of comorbidities in elderly patients leads to reduced physiological reserve and increased susceptibility to perioperative complications[16]. Outcomes can vary widely, depending on the clinical presentation and whether the procedure is performed electively or as an emergency.

Increasing age has previously been identified as a factor which significantly reduces the likelihood of emergency and elective cholecystectomy being undertaken[12]. One of the reasons quoted for this choice was the reduced life expectancy of this group of patients. The decision about the most appropriate treatment for these patients is always challenging for the surgeon, regardless of the pattern of onset.

The purpose of this study is to assess the risks in terms of morbidity of the octogenarian patients treated with cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis (biliary colic, AC, BAP) in order to provide useful data that could help surgeons in the decision process leading to both emergency and elective surgery in this particular population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A single center retrospective cohort study was conducted on patients who underwent cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis between September 2010 and October 2019. Exclusion criteria were age < 80 years and cholecystectomies performed during other surgical procedures. Data were extracted from a retrospective institutional review board-approved database (C.E.ROM. prot. 3238/2019; I.5/263) on hepatobiliary pancreatic surgery.

Diagnosis of cholelithiasis was performed based on imaging studies: ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance (MR). AC was diagnosed and graded according to the Tokyo Guidelines (TG18)[17]. Postoperative complications were defined according to the Clavien- Dindo classification[18]. The analyzed variables included patients- age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists scale (ASA), Body Mass Index (BMI), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)[19], comorbidity, prior abdominal surgery, laboratory test, radiological imaging, Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-Pancreatography (ERCP), diagnosis at admission in urgency; disease- cholelithiasis, cholangitis, AC, TG 18 score; and operation-related- timing, admission surgery interval, surgical approach, associated procedures, operative time, afternoon or night procedure, post-operative complication according to Clavien-Dindo classification, length of hospital stay, supported discharge, mortality.

Indications and procedures

Candidates for elective cholecystectomy were those patients with previous history of cholecystitis, biliary colic and/or biliary pancreatitis in the absence of biliary tract lithiasis. In case of choledocholithiasis in the preoperative work-up, in either election or emergency setting patients were referred for preoperative or intraoperative ERCP. Postoperative ERCP was indicated solely in case of choledocholithiasis diagnosed during intraoperative cholangiography in absence of contraindications for endoscopic treatment. The indications for choledocholithotomy were the failure to resolve choledochal lithiasis endoscopically or percutaneously (including by intraoperative Rendez-vous) and Mirizzi’s syndrome type 2.

The laparoscopic approach was performed with the patient placed in the French position. The first 10-12 mm trocar is inserted with an open technique in peri-umbilical area to achieve a 11 mmHg pneumoperitoneum. The other three trocars are positioned under direct vision in the epigastrium (5 mm), 1 Laterally in the right flank (5 mm) and 1 medially in the left flank (10 or 5 mm). In case of open conversion, access with a right subcostal laparotomy was preferred. Antibiotic prophylaxis with 3rd gen cephalosporins was administered in all patients. In case of AC a combination of antibiotics was used and continued based on clinical grounds.

In urgency and elective settings the open approach was indicated in high risk patients who had previous gastric surgery or repeated open abdominal surgery, in patients who need a surgical clearance of the common bile duct, in case of anesthetic contraindications to laparoscopy and in case of patient refusal to laparoscopy.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using MedCalc Statistical Software version 15.8 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2015). Continuous variables were shown as median and interquartile range (IQR) while categorical data were presented as numbers and percentages. Differences between complicated and uncomplicated patients were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and with the Chi square or Fisher exact tests for the categorical ones.

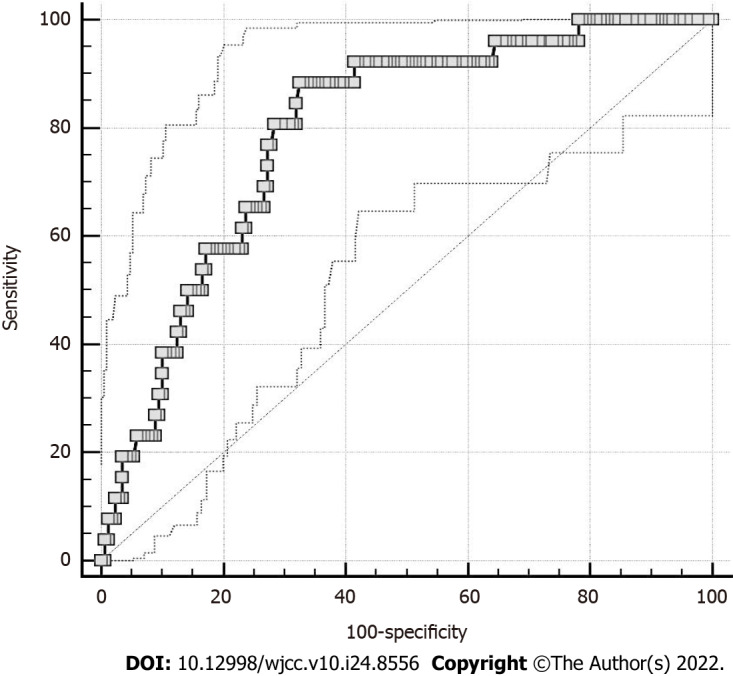

Logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the predictors of complications and major complications. The variables who displayed a P < 0.05 at multivariable analysis for Clavien-Dindo < 2 complications were merged in a model and its accuracy was assessed with a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to calculate the Area Under the curve (AUC).

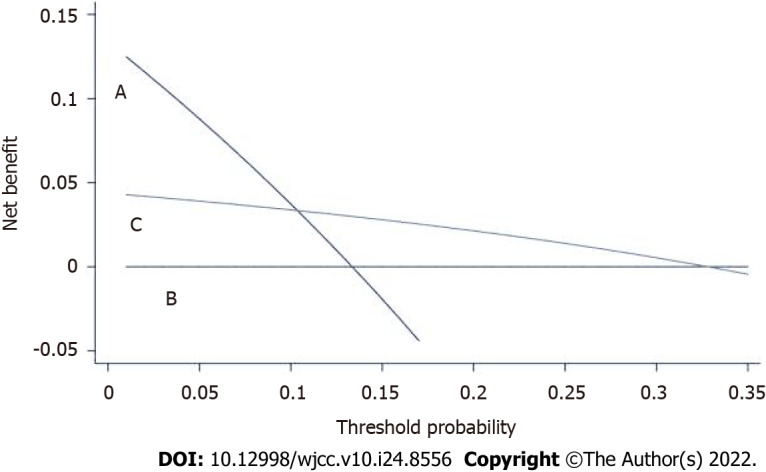

Decision curve analysis (DCA) was constructed using STATA version 15 (STATA Corp., TX, United States). DCA allowed the calculation of a clinical benefit for the prediction model in comparison with default strategies of operating all or no patient [20,21]. The DCA graph has on the y-axis the “net benefit” and on the x-axis the “threshold probability” (Pt).

The Net benefit could be calculated as follows: Net = (TP/n−FP/n)×(Pt/1−Pt).

TP and the FP are the number of patients with true- and false-positive results, respectively; n was the total number of patients, and Pt is the threshold probability of Clavien-Dindo > 2 complications. Thus, the “decision curve” resulted from plotting the Net benefit against the threshold probability and, in this study, it was used to test the utility of the constructed model in influencing the indication of performing or not the cholecystectomy in the given population. Each graph showed a curve representing the proposed model, one about performing cholecystectomy on all patients (treat all) and one about treating all patients with conservative treatment (treat none).

The study was reviewed by our expert biostatistician Leonardo Solaini, MD.

RESULTS

Overall, 269 patients (179 urgent vs 90 elective cholecystectomies) were included in the analysis. Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. Overall, 193 (71.7%) patients had a complicated postoperative course (Table 2). ASA score was significantly higher in the patients who had postoperative complications (P = 0.002). Median leukocyte (12850 versus 9300, P = 0.009) and platelets (272000 vs 197000, P < 0.0001) counts at admission were higher in the complicated group. Bilirubin levels were lower in patients who did not have any postoperative complications (0.82 vs 1.11, P = 0.011). The open approach (23.8% vs 13.0%) was more common in the group who had postoperative complications (P = 0.012). The complicated group had more intraoperative cholangiography (46.1 vs 65.3%). The uncomplicated group had more cholecystectomies which were performed during afternoon/night (31.6 vs 48.2%, P = 0.014).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics and their comparison according to the occurrence of postoperative complications

|

Variables

|

Total cohort (n = 269)

|

Uncomplicated (n = 76)

|

Complicated (n = 193)

|

P

value

|

| Age | 83 | 83 (82-85) | 83 (82-87) | 0.686 |

| Sex (M:F) | 126:143 | 344:200 | 92:101 | 0.686 |

| ASA | ||||

| 1 | 1 (0.0) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0.002 |

| 2 | 62 (23.0) | 27 (35.5) | 35 (18.1) | |

| 3 | 179 (66.5) | 48 (63.2) | 131 (67.9) | |

| 4 | 27 (10.0) | 1(1.3) | 26 (13.5) | |

| BMI | 24.8 (24-25.1) | 26.3 (22.9-28.2) | 24.2 (21.1-27.4) | 0.062 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 3 (1-4) | 3 (2-4) | 2 (1-4) | 0.145 |

| Prior upper abdomen surgery | 34 (12.6) | 11 (32.3) | 23 (67.7) | 0.548 |

| Leucocytes (× 109/L) | 11685 (10520-12957) | 9300 (7315-13917) | 12850 (8020-18200) | 0.009 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 236 (183-352) | 197 (165-262) | 272 (189-340) | < 0.0001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.01 (0.58-1.91) | 0.82 (0.41-1.53) | 1.11 (0.62-2.1) | 0.011 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 82 (19.7-225) | 46.4 (9-184.6) | 85.7 (22.2-231.0) | 0.135 |

| Antiplatelet | 110 (40.9) | 28 (36.8) | 82 (42.5) | 0.412 |

| Anticoagulant therapy | 64 (23.8) | 12 (15.8) | 52 (26.9) | 0.057 |

| Acute cholecystitis Tokyo grade | 0.147 | |||

| Mild | 36 (20.1) | 11(14.5) | 25 (13) | |

| Moderate | 75 (42.0) | 18 (23.7) | 57 (29.6) | |

| Severe | 68 (37.9) | 10 (13.2) | 58 (30.0) | |

| Diagnosis at admission in urgency | 0.374 | |||

| A.C. | 69 (38.5) | 19 (27.6) | 50 (72.4) | |

| A.C. + cholangitis | 19 (10.6) | 1 (5.2) | 18 (94.8) | |

| A.C. + choleperitoneum | 25 (14.0) | 5 (20) | 20 (80) | |

| A.C. + biliary colic | 38 (21.2) | 9 (23.7) | 29 (76.3) | |

| A.C. + biliary pancreatitis | 28 (15.7) | 7 (25) | 21(75) | |

| Preoperative ERCP | 23 (8.6) | 11 (14.5) | 12 (6.2) | 0.053 |

| Admission-surgery interval | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-3) | 0.051 |

| Operative time (min) | 100 (73-141) | 90 (66-120) | 105 (75-150) | 0.021 |

| Surgical approach | 0.012 | |||

| Laparoscopy | 53 | 115 | ||

| Open | 6 (7.9) | 46 (23.8) | ||

| Converted to open | 17 (23.4) | 32(16.6) | ||

| Intraoperative cholangiography | 161 (58.9) | 35 (46.1) | 126 (65.3) | 0.0005 |

| Choledocholithotomy | 15 (5.6) | 4 (5.3) | 11 (5.7) | 1 |

| Transcystic biliary decompression | 22 (8.2) | 3 (3.9) | 19 (9.8) | 0.147 |

| Intraoperative ERCP | 28 (10.4) | 6 (7.9) | 22 (11.4) | 0.508 |

| Afternoon night-procedure | 117 (43.5) | 24 (31.6) | 93(48.2) | 0.014 |

| Length of hospital stay | 5 (3-8) | 3 (2-6) | 6 (4-9) | < 0.0001 |

| Supported discharge | 47 (17.5) | 9 (11.9) | 38 (19.7) | 0.154 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI: Body mass index; A.C.: Acute cholecystitis; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography.

Table 2.

Detailed postoperative complications according to the Clavien Dindo scale

|

|

Election

|

Urgency

|

| Grade 1 | 31 | 54 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 18 | 6 |

| Pain | 13 | 48 |

| Grade 2 | 19 | 59 |

| Pneumonia | 6 | 13 |

| Mild pancreatitis | 0 | 7 |

| Ileus-delayed flatus | 5 | 16 |

| Septic status | 0 | 12 |

| Urinary problems | 8 | 11 |

| Grade 3 | 3 | 13 |

| Bile leak | 0 | 3 |

| Cholangitis/retained CBD stone | 1 | 6 |

| Bleeding | 1 | 3 |

| Respiratory failure | 1 | 1 |

| Grade 4 | 0 | 10 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0 | 1 |

| Arrhythmia | 0 | 3 |

| Respiratory failure | 0 | 2 |

| Acute renal failure | 0 | 4 |

| Grade 5 | 0 | 4 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0 | 3 |

| Pulmonary failure | 0 | 1 |

CBD: Common bile duct.

The 9.7% (n = 26) of complications were grade 3 or 4 according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. The in-hospital mortality rate was 1.5% (n = 4) while the 90 d mortality rate was 3.9% (n = 7). The three patients who died after discharge but within 90 days of surgery had had a postoperative course with Clavien-Dindo grade < 3 (Table 2). All cases of postoperative deaths occurred after open or converted urgent cholecystectomy.

At 24 mo follow-up, 195 were alive (85.9%) while 32 (14.1%) died for unrelated causes. For 23 (8.8%) patients last follow-up was at 90 days. At multivariable analysis, performing an intraoperative cholangiography (2.99, 1.43-6.24; P = 0.003), the diagnosis of cholangitis at admission (12.7, 1.61-100.1; P = 0.016), platelets count (1.00, 1.00-1.01; P = 0.0008), the laparoscopic approach (0.10, 0.02-0.46; P = 0.003) were significantly associated with postoperative complications (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for postoperative complications

|

Variables

|

Univariate analysis

|

P

value

|

Multivariate analysis

|

P value |

|

OR (95%CI)

|

OR (95%CI)

|

|||

| Age | 1.00 (0.93-1.08) | 0.864 | ||

| Sex | 0.85 (0.50-1.46) | 0.562 | ||

| ASA | ||||

| 1 | NA | NA | ||

| 2 | 0.51 (0.28-0.93) | 0.027 | ||

| 3 | Ref. | 1 | ||

| 4 | 9.53 (1.26-72.1) | 0.029 | ||

| BMI | 0.92 (0.85-1.01) | 0.072 | ||

| CCI | 0.82 (0.43-1.60 | 0.611 | ||

| Prior upper abdomen surgery | 0.79 (0.36-1.72) | 0.559 | ||

| Leucocytes | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.009 | ||

| Platelets | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.013 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.0008 |

| Bilirubin | 1.23 (0.97-1.57) | 0.081 | ||

| C-reactive protein | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.195 | ||

| Antiplatelet | 1.33 (0.77-2.31) | 0.311 | ||

| Anticoagulant therapy | 1.922 (0.96-3.85) | 0.065 | ||

| Acute cholecystitis Tokyo grade | ||||

| Mild | 1.55 (0.67-3.35) | 0.324 | ||

| Moderate | 2.19 (1.11-4.32) | 0.023 | ||

| Severe | 4.54 (2.00-10.3) | 0.0003 | ||

| BIliary colic | 3.43 (1.70-6.93) | 0.0006 | ||

| Biliary pancreatitis | 1.24 (0.51-3.04) | 0.635 | ||

| Gallbladder cancer | 1.95 (0.22-17.1) | 0.543 | ||

| Choleperitoneum | 1.61 (0.58-4.45) | 0.36 | ||

| Cholangitis | 12.0 (1.59-89.7) | 0.019 | 12.7 (1.61-100.1) | 0.016 |

| Preoperative ERCP | 0.38 (0.16-0.91) | 0.03 | ||

| Admission-surgery interval | 1.04 (0.95-1.14) | 0.326 | ||

| Laparoscopy | 0.28 (0.11-0.69) | 0.005 | 0.10 (0.02-0.46) | 0.003 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 1.81 (0.37-1.42) | 0.354 | ||

| Choledocholithotomy | 1.07 (0.33-3.46) | 0.914 | ||

| Intraoperative cholangiography | 2.12 (1.23-3.64) | 0.007 | 2.99 (1.43-6.24) | 0.003 |

| Intraoperative ERCP | 1.47 (0.57-3.78) | 0.423 | ||

| Transcystic biliary decompression | 2.57 (0.73-8.95) | 0.138 | ||

| Afternoon night procedure | 2.12 (1.21-3.74) | 0.009 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI: Body mass index; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography; CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; NA: Not available.

ASA 4 patients (12.6, 4.27-37.3; P < 0.0001), performing a choledocholithotomy (10.2, 2.04-51.1; P = 0.005) and bilirubin levels (1.4, 1.33-1.75; P = 0.002) were significantly associated with Clavien-Dindo > 2 complications (Table 4) for the whole population.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for postoperative complications with Clavien-Dindo grade > 2

| Variables |

Univariate analysis

|

P

value

|

Multivariate analysis

|

P value |

|

OR (95%CI)

|

OR (95%CI)

|

|||

| Age | 1.08 (0.98-1.18) | 0.122 | ||

| Sex | 0.64 (0.30-1.38) | 0.255 | ||

| ASA | ||||

| 1 | NA | |||

| 2 | 0.14 (0.02-1-12) | 0.064 | ||

| 3 | Ref. | 1 | ||

| 4 | 6.14 (2.48-15.3) | 0.001 | 12.6 (4.27-37.3) | < 0.0001 |

| BMI | 1.12 (1.00-1.26) | 0.05 | ||

| CCI | 1.19 (0.87-4.21) | 0.237 | ||

| Prior upper abdomen surgery | 1.92 (0.72-5.12) | 0.193 | ||

| Leucocytes | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.021 | ||

| Platelets | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.545 | ||

| Bilirubin | 1.37 (0.44-4.28) | 0.014 | 1.41 (1.33-1.75) | 0.002 |

| C-reactive protein | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.252 | ||

| Antiplatelet | 0.96 (0.44-2.08) | 0.916 | ||

| Anticoagulant therapy | 2.03 (0.91-4.53) | 0.083 | ||

| Acute cholecystitis Tokyo grade | ||||

| Mild | 3.33 (0.71-15.7) | 0.128 | ||

| Moderate | 3.38 (0.86-13.2) | 0.08 | ||

| Severe | 8.02 (2.21-29.0) | 0.001 | ||

| Biliary colic | 0.79 (0.33-1.87) | 0.599 | ||

| Biliary pancreatitis | 0.26 (0.03-1.98) | 0.194 | ||

| Choleperitoneum | 2.89 (1.05-7.95) | 0.039 | ||

| Cholangitis | 1.37 (0.44-4.28) | 0.579 | ||

| Preoperative ERCP | 0.74 (0.16-3.33) | 0.696 | ||

| Admission-surgery interval | 1.05 (0.99-1.11) | 0.115 | ||

| Laparoscopy | 0.18 (0.08-0.40) | < 0.001 | ||

| Conversion to open surgery | 1.81 (0.75-4.35) | 0.185 | ||

| Choledocholithotomy | 4.58 (1.45-14.5) | 0.009 | 10.2 (2.04-51.1) | 0.005 |

| Transcystic biliary decompression | 5.81 (2.20-15.4) | 0.0004 | ||

| Intraoperative cholangiography | 0.86 (0.40-1.86) | 0.706 | ||

| Intraoperative ERCP | 1.38 (0.44-4.28) | 0.579 | ||

| Afternoon night procedure | 1.82 (0.84-3.91) | 0.126 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI: Body mass index; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography; CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; NA: Not available.

The ROC curve analysis showed that the model including the three variables to predict Clavien-Dindo > 2 complications had an AUC of 0.79 (0.73-0.85) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve representing the accuracy of the model.

The decision curve analysis is shown in Figure 2. According to the graph, the treating all strategy may be harmful in terms of Clavien-Dindo > 2 complications in patients with threshold probabilities > 13%. The proposed model showed a higher Net benefit than the treating all/none options between threshold probabilities of 11% and 32% of developing a Clavien-Dindo > 2 complication.

Figure 2.

Decision curve analysis of Clavien-Dindo > 2 complications following cholecystectomy for gallstone disease. Decision curve analysis included three main strategies: to perform cholecystectomy on all patients; the net benefit of surgery to none patients; to treat the patients according the proposed model (Net Benefit: CL2). A: Treat all; B: Treat none; C: Proposed model.

DISCUSSION

Even though gallstones increase with aging, older patients are less likely to undergo cholecystectomy[1,22]. In fact, it has been estimated that less than a quarter of elderly patients who meet the criteria for elective cholecystectomy undergo surgery[1,22]. This is because increasing age is a negative predictor after cholecystectomy, due to the higher perceived surgical risks, especially after hospitalization for complications of gallstones[1]. In this clinical arena, the availability of a tool to support the surgeon in his decision making is of utmost importance.

Cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstone disease is associated with a high postoperative complication rate in octogenarians. However, it must be highlighted that only 9.7% of patients had a severe complication, indicating that cholecystectomy could remain a treatment option in this population. In line with this assumption, the NICE 2014[23] and TG18[17] guidelines did not suggest an age cut-off to surgically treat symptomatic gallstone disease or cholecystitis.

Other reports showed similar high morbidity rates ranging between 14.7% and 51%[24-27].

Only 3 studies with populations with similar characteristics reported complications graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification and all found that the majority of complications were Clavien-Dindo grade 1-2 characteristics [28-30].

The feasibility of cholecystectomy in octogenarians was evaluated in different studies that confirmed its safety, but in the investigated “all comers” groups the surgical treatment in an elective setting always represented more than half of the cases[28]. Differently, the population analyzed in this study was characterized by a limited number of patients (33.5%) treated electively with cholecystectomy.

In addition, according to our analysis, cholecystectomy seemed to be associated with acceptable safety parameters in moderate-severe acute cholecystitis. As such, 90 d mortality in our cohort was 2.6%. This is similar to what has been reported by the two largest single-center studies which showed in-hospital mortality ranging between 4% to 4.8%[28,31].This was also confirmed by a recent systematic review comparing the outcomes of patients with 65-79 vs ≥ 80 years which showed a mortality rate of 0%-4.6% in the older age group[5].

A severely complicated postoperative course, may have a dramatic impact on the elderly patients who may not return to their previous level of activity[32].

Our analysis could find those factors which could help in predicting those patients at risk of having a severely complicated postoperative course.

According to the decision curve analysis our model may be of use in selecting those elderly patients at the lowest risk of severe complications for whom cholecystectomy should be performed.

We found that ASA 4 patients with elevated bilirubin levels and in need of choledocholithotomy had the highest risk of developing a Clavien-Dindo > 2 complication. The risk of a Clavien-Dindo > 2 complication was nearly 80% for this subgroup of patients.

This may indicate the need of considering alternative non-operative approaches for this subgroup of patients, preferring endoscopic/percutaneous options.

Our paper appears to be the first in the literature to document a statistically significant correlation between the use of choledocholithotomy and complications.[33,34] This may be due to the fact that our analysis focused on a very select population of patients with > 80 years of age. This finding may suggest considering a surgical-endoscopic 'rendez-vous' procedure as an alternative to choledocholithotomy[35]. However, additional studies on this approach on the oldest-old populations are warranted to confirm this hypothesis.

The limitations of this study are linked to its retrospective nature whose outcomes may be confounded by selection bias. As such, the cohort may include the fittest patients, for whom a definitive treatment like cholecystectomy may not represent a major risk. In addition, we could not provide data on frailty which may be another factor to consider when dealing with the oldest-old patients. This might have helped in creating an even more accurate model in predicting patients at risk for severe postoperative complications following cholecystectomy for gallstone disease. Finally, since the study is based on a surgical database, we could not consider those patients treated only with percutaneous/endoscopic procedures which might be considered a treatment option for a subpopulation of octogenarians.

CONCLUSION

ASA 4 patients with higher levels of bilirubin at admission who may need a choledocholithotomy are at the highest risk of a severely complicated postoperative course. These factors should be included in the decision-making process in defining the ideal elderly patients to be submitted to cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis in either an emergency or elective setting.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Incidence of gallstones in those aged ≥ 80 years is as high as 38%-53%. This population is at higher risk of complication following cholecystectomy with postoperative morbidity rates up to over 50%.

Research motivation

The decision-making process for selecting patients undergoing surgery is challenging. A model which can identify the patients at the highest risk would be helpful for selecting the ideal candidate for cholecystectomy in a population aged ≥ 80 years.

Research objectives

The purpose of this study is to assess the perioperative risk of the octogenarian patients treated with cholecystectomy and to create a model that could help surgeons in the decision-making process leading to surgery in this population.

Research methods

An institutional review board-approved database was exploited to analyze all patients aged ≥ 80 years who had cholecystectomy between 2010 and 2019. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the perioperative variables associated with postoperative complications. Then a model was created and tested to predict severe postoperative morbidity.

Research results

Clavien-Dindo complications rate > 2 was 9.7%. A model including American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scale 4 patients, performing a choledocholithotomy and bilirubin levels were associated with Clavien-Dindo > 2 complications (P < 0.001). The decision curve analysis showed that the proposed model had a higher net benefit than the treating all/none options between threshold probabilities of 11% and 32% of developing a severe complication.

Research conclusions

Patients with ASA 4, higher level of bilirubin and need of choledocholithotomy are at the highest risk of a severely complicated postoperative course.

Research perspectives

Future analyses confirming these results should focus on alternative endoscopic or percutaneous treatments that may be more suitable treatments for this subgroup of octogenarian.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Dr. Angelo Paolo Ciarrocchi for revising the language editing.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of ROMAGNA CEROM (10/04/2019) (Approval No. 3238/2019 I.5/263).

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: April 27, 2022

First decision: May 30, 2022

Article in press: July 22, 2022

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dai YC, China; Sato M, Japan; Zarnescu NO, Romania S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

Contributor Information

Fabrizio D'Acapito, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy.

Leonardo Solaini, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy; Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna 40126, Italy. leonardo.solaini2@unibo.it.

Daniela Di Pietrantonio, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy.

Francesca Tauceri, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy.

Maria Teresa Mirarchi, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy.

Elena Antelmi, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy.

Francesca Flamini, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy.

Alessio Amato, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy.

Massimo Framarini, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy.

Giorgio Ercolani, Department of General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì 47121, Italy; Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna 40126, Italy.

Data sharing statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due privacy policies but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Bergman S, Sourial N, Vedel I, Hanna WC, Fraser SA, Newman D, Bilek AJ, Galatas C, Marek JE, Monette J. Gallstone disease in the elderly: are older patients managed differently? Surg Endosc. 2011;25:55–61. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergman S, Al-Bader M, Sourial N, Vedel I, Hanna WC, Bilek AJ, Galatas C, Marek JE, Fraser SA. Recurrence of biliary disease following non-operative management in elderly patients. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3485–3490. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsui Y, Hirooka S, Sakaguchi T, Kotsuka M, Yamaki S, Yamamoto T, Kosaka H, Satoi S, Sekimoto M. Bile Duct Stones Predict a Requirement for Cholecystectomy in Older Patients. World J Surg. 2020;44:721–729. doi: 10.1007/s00268-019-05241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekici U, Yılmaz S, Tatlı F. Comparative Analysis of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Performed in the Elderly and Younger Patients: Should We Abstain from Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in the Elderly? Cureus. 2018;10:e2888. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lord AC, Hicks G, Pearce B, Tanno L, Pucher PH. Safety and outcomes of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the extremely elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Chir Belg. 2019;119:349–356. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2019.1658356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed I, Innes K, Brazzelli M, Gillies K, Newlands R, Avenell A, Hernández R, Blazeby J, Croal B, Hudson J, MacLennan G, McCormack K, McDonald A, Murchie P, Ramsay C. Protocol for a randomised controlled trial comparing laparoscopic cholecystectomy with observation/conservative management for preventing recurrent symptoms and complications in adults with uncomplicated symptomatic gallstones (C-Gall trial) BMJ Open. 2021;11:e039781. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epari KP, Mukhtar AS, Fletcher DR, Samarasam I, Semmens JB. The outcome of patients on the cholecystectomy waiting list in Western Australia 1999-2005. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:703–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurusamy KS, Davidson BR. Surgical treatment of gallstones. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:229–244, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray AC, Markar S, Mackenzie H, Baser O, Wiggins T, Askari A, Hanna G, Faiz O, Mayer E, Bicknell C, Darzi A, Kiran RP. An observational study of the timing of surgery, use of laparoscopy and outcomes for acute cholecystitis in the USA and UK. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:3055–3063. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-6016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, Dellon ES, Eluri S, Gangarosa LM, Jensen ET, Lund JL, Pasricha S, Runge T, Schmidt M, Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Burden of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1731–1741.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akasu T, Kinoshita A, Imai N, Hirose Y, Yamaguchi R, Yokota T, Iwaku A, Koike K, Saruta M. Clinical characteristics and short-term outcomes in patients with acute cholecystitis over aged >80 years. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19:208–212. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiggins T, Markar SR, Mackenzie H, Jamel S, Askari A, Faiz O, Karamanakos S, Hanna GB. Evolution in the management of acute cholecystitis in the elderly: population-based cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:4078–4086. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Heesewijk AE, Lammerts RGM, Haveman JW, Meerdink M, van Leeuwen BL, Pol RA. Outcome after cholecystectomy in the elderly. Am J Surg. 2019;218:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nassar Y, Richter S. Management of complicated gallstones in the elderly: comparing surgical and non-surgical treatment options. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2019;7:205–211. doi: 10.1093/gastro/goy046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamarajah SK, Karri S, Bundred JR, Evans RPT, Lin A, Kew T, Ekeozor C, Powell SL, Singh P, Griffiths EA. Perioperative outcomes after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4727–4740. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07805-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Botto F, Alonso-Coello P, Chan MT, Villar JC, Xavier D, Srinathan S, Guyatt G, Cruz P, Graham M, Wang CY, Berwanger O, Pearse RM, Biccard BM, Abraham V, Malaga G, Hillis GS, Rodseth RN, Cook D, Polanczyk CA, Szczeklik W, Sessler DI, Sheth T, Ackland GL, Leuwer M, Garg AX, Lemanach Y, Pettit S, Heels-Ansdell D, Luratibuse G, Walsh M, Sapsford R, Schünemann HJ, Kurz A, Thomas S, Mrkobrada M, Thabane L, Gerstein H, Paniagua P, Nagele P, Raina P, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ, McQueen MJ, Bhandari M, Bosch J, Buckley N, Chow CK, Halliwell R, Li S, Lee VW, Mooney J, Furtado MV, Suzumura E, Santucci E, Leite K, Santo JA, Jardim CA, Cavalcanti AB, Guimaraes HP, Jacka MJ, McAlister F, McMurtry S, Townsend D, Pannu N, Bagshaw S, Bessissow A, Duceppe E, Eikelboom J, Ganame J, Hankinson J, Hill S, Jolly S, Lamy A, Ling E, Magloire P, Pare G, Reddy D, Szalay D, Tittley J, Weitz J, Whitlock R, Darvish-Kazim S, Debeer J, Kavsak P, Kearon C, Mizera R, O'Donnell M, McQueen M, Pinthus J, Ribas S, Simunovic M, Tandon V, Vanhelder T, Winemaker M, McDonald S, O'Bryne P, Patel A, Paul J, Punthakee Z, Raymer K, Salehian O, Spencer F, Walter S, Worster A, Adili A, Clase C, Crowther M, Douketis J, Gangji A, Jackson P, Lim W, Lovrics P, Mazzadi S, Orovan W, Rudkowski J, Soth M, Tiboni M, Acedillo R, Garg A, Hildebrand A, Lam N, Macneil D, Roshanov PS, Srinathan SK, Ramsey C, John PS, Thorlacius L, Siddiqui FS, Grocott HP, McKay A, Lee TW, Amadeo R, Funk D, McDonald H, Zacharias J, Cortés OL, Chaparro MS, Vásquez S, Castañeda A, Ferreira S, Coriat P, Monneret D, Goarin JP, Esteve CI, Royer C, Daas G, Choi GY, Gin T, Lit LC, Sigamani A, Faruqui A, Dhanpal R, Almeida S, Cherian J, Furruqh S, Afzal L, George P, Mala S, Schünemann H, Muti P, Vizza E, Ong GS, Mansor M, Tan AS, Shariffuddin II, Vasanthan V, Hashim NH, Undok AW, Ki U, Lai HY, Ahmad WA, Razack AH, Valderrama-Victoria V, Loza-Herrera JD, De Los Angeles Lazo M, Rotta-Rotta A, Sokolowska B, Musial J, Gorka J, Iwaszczuk P, Kozka M, Chwala M, Raczek M, Mrowiecki T, Kaczmarek B, Biccard B, Cassimjee H, Gopalan D, Kisten T, Mugabi A, Naidoo P, Naidoo R, Rodseth R, Skinner D, Torborg A, Urrutia G, Maestre ML, Santaló M, Gonzalez R, Font A, Martínez C, Pelaez X, De Antonio M, Villamor JM, García JA, Ferré MJ, Popova E, Garutti I, Fernández C, Palencia M, Díaz S, Del Castillo T, Varela A, de Miguel A, Muñoz M, Piñeiro P, Cusati G, Del Barrio M, Membrillo MJ, Orozco D, Reyes F, Sapsford RJ, Barth J, Scott J, Hall A, Howell S, Lobley M, Woods J, Howard S, Fletcher J, Dewhirst N, Williams C, Rushton A, Welters I, Pearse R, Ackland G, Khan A, Niebrzegowska E, Benton S, Wragg A, Archbold A, Smith A, McAlees E, Ramballi C, Macdonald N, Januszewska M, Stephens R, Reyes A, Paredes LG, Sultan P, Cain D, Whittle J, Del Arroyo AG, Sun Z, Finnegan PS, Egan C, Honar H, Shahinyan A, Panjasawatwong K, Fu AY, Wang S, Reineks E, Blood J, Kalin M, Gibson D, Wildes T. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a large, international, prospective cohort study establishing diagnostic criteria, characteristics, predictors, and 30-day outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:564–578. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Wakabayashi G, Kozaka K, Endo I, Deziel DJ, Miura F, Okamoto K, Hwang TL, Huang WS, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Noguchi Y, Shikata S, Ukai T, Higuchi R, Gabata T, Mori Y, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Jagannath P, Jonas E, Liau KH, Dervenis C, Gouma DJ, Cherqui D, Belli G, Garden OJ, Giménez ME, de Santibañes E, Suzuki K, Umezawa A, Supe AN, Pitt HA, Singh H, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Teoh AYB, Honda G, Sugioka A, Asai K, Gomi H, Itoi T, Kiriyama S, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Matsumura N, Tokumura H, Kitano S, Hirata K, Inui K, Sumiyama Y, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:41–54. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vickers AJ. Decision analysis for the evaluation of diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular markers. Am Stat. 2008;62:314–320. doi: 10.1198/000313008X370302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:565–574. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riall TS, Adhikari D, Parmar AD, Linder SK, Dimou FM, Crowell W, Tamirisa NP, Townsend CM Jr, Goodwin JS. The risk paradox: use of elective cholecystectomy in older patients is independent of their risk of developing complications. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:682–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warttig S, Ward S, Rogers G Guideline Development Group. Diagnosis and management of gallstone disease: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;349:g6241. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuy S, Sosa JA, Roman SA, Desai R, Rosenthal RA. Age matters: a study of clinical and economic outcomes following cholecystectomy in elderly Americans. Am J Surg. 2011;201:789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oldani A, Calabrò M, Maroso F, Deiro G, Ravizzini L, Gentile V, Magaton C, Amato M, Gentilli S. Early surgical management of acute cholecystitis in ultra-octogenarian patients: our 5-year experience. Minerva Chir. 2019;74:203–206. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4733.18.07719-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loozen CS, van Ramshorst B, van Santvoort HC, Boerma D. Early Cholecystectomy for Acute Cholecystitis in the Elderly Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Surg. 2017;34:371–379. doi: 10.1159/000455241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lupinacci RM, Nadal LR, Rego RE, Dias AR, Marcari RS, Lupinacci RA, Farah JF. Surgical management of gallbladder disease in the very elderly: are we operating them at the right time? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:380–384. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835b7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De la Serna S, Ruano A, Pérez-Jiménez A, Rojo M, Avellana R, García-Botella A, Pérez-Aguirre E, Diez-Valladares LI, Torres AJ. Safety and feasibility of cholecystectomy in octogenarians. Analysis of a single center series of 316 patients. HPB (Oxford) 2019;21:1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2019.03.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunt LM, Quasebarth MA, Dunnegan DL, Soper NJ. Outcomes analysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the extremely elderly. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:700–705. doi: 10.1007/s004640000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costi R, DiMauro D, Mazzeo A, Boselli AS, Contini S, Violi V, Roncoroni L, Sarli L. Routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis in octogenarians: is it worth the risk? Surg Endosc. 2007;21:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novello M, Gori D, Di Saverio S, Bianchin M, Maestri L, Mandarino FV, Cavallari G, Nardo B. How Safe is Performing Cholecystectomy in the Oldest Old? World J Surg. 2018;42:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desserud KF, Veen T, Søreide K. Emergency general surgery in the geriatric patient. Br J Surg. 2016;103:e52–e61. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X, Huang ZJ, Zhong JY, Ran YH, Ma ML, Zhang HW. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with primary closure is safe for management of choledocholithiasis in elderly patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2019;18:557–561. doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paganini AM, Feliciotti F, Guerrieri M, Tamburini A, Campagnacci R, Lezoche E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and common bile duct exploration are safe for older patients. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1302–1308. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.La Barba G, Gardini A, Cavargini E, Casadei A, Morgagni P, Bazzocchi F, D'Acapito F, Cavaliere D, Curti R, Tringali D, Cucchetti A, Ercolani G. Laparoendoscopic rendezvous in the treatment of cholecysto-choledocholitiasis: a single series of 200 patients. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:3868–3873. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due privacy policies but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.