Abstract

Physical rehabilitation is an effective therapy to normalize weaknesses encountered with neurological disorders such as traumatic brain injury (TBI). However, the efficacy of exercise is limited during the acute period of TBI because of metabolic dysfunction, and this may further compromise neuronal function. Here we discuss the possibility to normalize brain metabolism during the early post-injury convalescence period to support functional plasticity and prevent long-term functional deficits. Although BDNF possesses the unique ability to support molecular events involved with the transmission of information across nerve cells through activation of its TrkB receptor, the poor pharmacokinetic profile of BDNF has limited its therapeutic applicability. The flavonoid derivative, 7,8-dihydroxyflavone (7,8-DHF), signals through the same TrkB receptors and results in the activation of BDNF signaling pathways. We discuss how the pharmacokinetic limitations of BDNF may be avoided by the use of 7,8-DHF, which makes it a promising pharmacological agent for supporting activity-based rehabilitation during the acute post-injury period after TBI. In turn, docosahexaenoic acid (C22:6n-3; DHA) is abundant in the phospholipid composition of plasma membranes in the brain and its action is important for brain development and plasticity. DHA is a major modulator of synaptic membrane fluidity and function, which is fundamental for supporting cell signaling and synaptic plasticity. Exercise influences DHA function by normalizing DHA content in the brain, such that the collaborative action of exercise and DHA can be instrumental to boost BDNF function with strong therapeutic potential for reducing the deleterious effects of TBI on synaptic plasticity and cognition.

Keywords: Exercise, Traumatic brain injury, Brain, Synaptic plasticity, DHA, BDNF

Highlights

-

•

Exercise efficacy may be compromised during the acute period of brain injury.

-

•

Synergistic effects of BDNF agonist 7,8-DHF when used with exercise.

-

•

Synergistic effects of DHA on plasma membrane when used together with exercise.

Abbreviation list

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- 7,8-DHF

7,8-dihydroxyflavone

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid: C22:6n-3

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CREB

transcription factor cAMP-response-element-binding protein

- FPI

fluid percussion injury

- PGC-1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ co-activator-1α

- COII

cytochrome oxidase II

- AMPK

AMP activated protein kinase

- fMRI

Resting-state functional MRI

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major medical burden around the world involving domestic, sport, and military environments. In the United States, approximately 2.8–2.9 million emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths are related to TBI, costing annually an estimated $93 billion.1 The pathophysiology of TBI results from mechanical forces of an impact on the head and is followed by longer-lasting sequelae involving impaired metabolic function, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, increased blood-brain barrier permeability, and functional impairments in cognition and motor capacities.2

TBI treatment applied during its acute phase has been shown to prevent secondary injury by maintaining cerebral perfusion pressure and blood flow and protecting against hypotension and hypoxia.3 Post-acute treatment is targeted toward secondary effects that can extend for months or years, often affecting cognitive and emotional capacities. Pharmacological treatment used to reduce neuroinflammation and provide neuroprotection have shown little success in clinical practice.2,4 In the face of limited clinical success for pharmacological treatment modalities, new therapeutic strategies are sorely needed. Particularly, alternative and non-invasive treatments such as nutritional supplements are being explored,5 and currently, the most prevalent therapeutic treatment to promote functional recovery after TBI is physical rehabilitation.

Effects of exercise on cognitive abilities and TBI outcomes

Exercise is perceived as a necessary aspect of daily routine to maintain the overall health of the body and brain. In particular, abundant evidence supports the action of exercise on sharpening cognitive abilities throughout the lifespan such that the lack of exercise is considered a risk for the incidence of several neurological disorders. The beneficial impact of exercise on brain plasticity has been mostly associated with the action of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) on the brain and body,6 based on its involvement with neuronal regeneration, excitability, and cognitive enhancement.7 The influence of exercise on BDNF biology has been linked to hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning and memory involving various signaling systems such as CaMKII and the transcription regulator CREB.6

The positive actions of exercise on learning and memory in humans and animals have received abundant support.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 In older adults, exercise has been shown to improve cognitive performance13,14 and to counteract mental decline associated with aging,15,16 and these effects have been associated with modifications in hippocampal size.10 In schoolchildren, exercise has been found to be associated with the cognitive performance: children who engaged in greater amounts of aerobic exercise generally performed better on verbal, perceptual, and mathematical tests.17 Exercise is also perceived as one of the most effective therapies to reduce depression across the lifespan.18 Furthermore, studies in rodents have shown the utility of exercise to promote cognitive recovery from a brain injury.19, 20, 21 Importantly, the memory improvements induced by physical exercise are accompanied by increases in cell proliferation, neurogenesis, dendritic complexity, and spine density.8,22,23

Clinical studies show that exercise therapy after TBI can improve patient outcomes, for example by improving emotional and cognitive deficits that often occur following brain injury.24 However, due to differences among individuals in terms of the extent and duration of the TBI, it is challenging to establish an effective clinical approach and there is currently no consensus as to the most effective post-TBI treatment window or recommended exercise intensity, requiring larger controlled trials.

Overcoming limitations of exercise intervention for TBI: 7,8-DHF can potentiate the action of exercise

Physical rehabilitation is an effective therapy to normalize some of the weaknesses encountered after TBI.24 However, the efficacy of exercise during metabolic depression is an important limitation as it can further compromise neuronal function. There is a need to normalize brain metabolism during the early post-injury convalescence period in order to support various mechanisms of functional plasticity to prevent long-term functional deficits. The fact that TBI imposes a state of brain vulnerability in which neurons perform at a suboptimal level, exposure to tasks involving activity can further compromise neuronal function.25 This period of neuronal vulnerability is particularly critical for TBI patients engaging in physical rehabilitation as it appears that the energy demand imposed by activity on neural circuits invalidates the use of exercise during the acute post-injury period when the brain is deficient in energy.25 Therefore, there is a pressing need to normalize brain metabolism during the early post-injury convalescence period in order to support functional plasticity to prevent long-term functional deficits.

There is a strong dependency on exercise for BDNF to accomplish several of its actions in the CNS and periphery. BDNF possesses the unique ability to support molecular events involved with the transmission of information across nerve cells and cell metabolism through activation of its TrkB receptor. However, the poor pharmacokinetic profile of BDNF 26 has limited its therapeutic applicability. The flavonoid derivative, 7,8-dihydroxyflavone (7,8-DHF), that signals through the same TrkB receptors and results in activation of BDNF signaling pathways,27 possesses a more favorable pharmacokinetic profile. Indeed, many of the pharmacokinetic limitations of BDNF are avoided by the use of 7,8-DHF, which makes it a promising pharmacological agent for supporting activity-based rehabilitation during the acute post-injury period after TBI.

While 7,8-DHF is considered a BDNF mimetic, it is a much smaller molecule with a circulating half-life that is more than 10-fold higher than that of BDNF.27 Further, 7,8-DHF has a proven safety profile and is a promising therapeutic agent27 with the potential to manifest all the therapeutic effects of BDNF – without the limitations. In particular, 7,8-DHF has been shown to provide protection against oxidative stress and glutamate toxicity,28 decrease infarct volumes in stroke, and reduce toxicity in an animal model of Parkinson's disease with significant blood-brain barrier penetration.29 In addition, in a rat model of TBI, injured animals treated with 7,8-DHF showed improved memory function, normalized levels of brain plasticity markers, and improvements in cell energy homeostasis compared to vehicle-treated animals,30 indicating that this small molecule may be an excellent candidate for the treatment of secondary injury mechanisms after TBI.

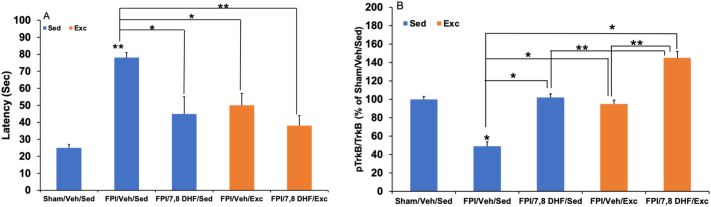

TBI impairs BDNF-TrkB signaling, which could account for the compromised plastic capacity and energy homeostasis that occurs at the earliest stages of brain injury.30 7,8-DHF greatly complements the action of exercise31 to fulfill the energy demands imposed by TBI (Fig. 1). In particular, the TrkB agonist 7,8-DHF normalizes brain energy deficits and reestablishes more normal patterns of functional connectivity during the post-TBI period. Moderate fluid percussion injury (FPI) was performed and 7,8-DHF (5 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered in animals subjected to FPI that had access to voluntary wheel running for 7 days after injury. While 7,8-DHF treatment and exercise individually mitigated TBI-induced effects, administration of 7,8-DHF concurrently with exercise facilitated memory performance and augmented levels of markers of cell energy metabolism peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ co-activator-1α (PGC-1α), cytochrome oxidase II (COII) and AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK). Resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) acquired 2 weeks after injury showed that 7,8-DHF with exercise enhanced hippocampal functional connectivity, and suggests 7,8-DHF and exercise to promote increases in functional connectivity. Signaling through the BDNF receptor activates the transcription factor cAMP-response-element-binding protein (CREB) which is an important regulator of PGC-1α. PGC-1α regulates mitochondrial biogenesis in close association with BDNF [5], and these actions lead to changes in COII expression through AMPK with nuclear-encoded proteins promoting mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) transcription. These results have important implications for post-injury rehabilitation therapy because they show that treatment with 7,8-DHF prepares the brain to benefit from earlier rehabilitation after injury by alleviating metabolic dysfunction and enhancing plasticity. These results strongly suggest that the combined actions of 7,8-DHF and exercise facilitate energy homeostasis during the early phases of TBI.

Fig. 1.

(A) 7,8-DHF and exercise elevates hippocampal levels of TrkB phosphorylation and the combination of exercise and 7,8-DHF show a synergistic effect among rats subjected to fluid percussion injury (FPI). Data are presented as percentage (%) of Sham/Veh/Sed (mean ± SEM). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test. (B) 7,8-dihydroxyflavone (7,8-DHF; 5 mg/kg, i.p.) or exercise reduced latency time in the Barnes maze in rodents subjected to FPI. The combination of 7,8-DHF and exercise show a synergistic trending effect in latency times. Data collected during a 5-min testing session are presented as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, relative to Sham/Veh/Sed; One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test.

DHA can help restore plasma membrane homeostasis

Another limitation encountered in TBI and other neurological disorders is the disruption of plasma membrane homeostasis,32 the appropriate function of which is integral to normal synaptic plasticity mechanisms.33 The plasma membrane is the site of regulation of signaling events that are crucial for neuronal functions that are disrupted in TBI such as excitatory neurotransmitter efflux,34 energy metabolism, and oxidative stress.35

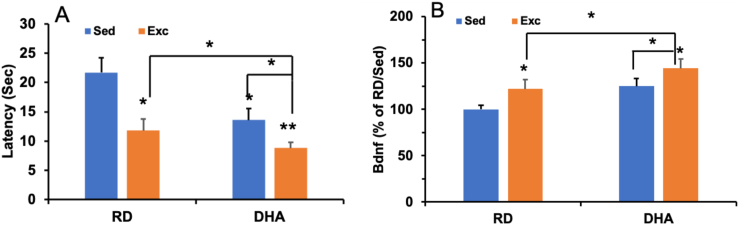

Docosahexaenoic acid (C22:6n-3; DHA) is abundant in the phospholipid composition of plasma membranes in the brain and its action is important for brain development and adult plasticity. DHA is a major modulator of synaptic membrane fluidity and function, which is fundamental for supporting cell signaling 36,37 and synaptic plasticity33,38 that are crucial for brain function and plasticity. We have found that a short 12-day exposure to a DHA-enriched diet significantly increases learning ability, and these effects are enhanced by the concurrent application of voluntary exercise.38 The effects of the DHA diet and exercise on cognitive enhancement were paralleled by elevations in BDNF, and the activated forms of the synaptic proteins CREB, synapsin I, and CaMKII, important for hippocampal learning. Levels of the Akt signaling system were also elevated in proportion to BDNF levels suggesting an action of BDNF on Akt signaling in our paradigm. The enhanced actions of the DHA diet and exercise on cognition and neuroplasticity suggest a possible mechanism by which specific aspects of lifestyle integrate their actions at the molecular level to influence neuronal vitality and function (Fig. 2) (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

(A) DHA and exercise improves learning performance in the Morris water maze. The results demonstrate that rodents fed a DHA-enriched perform better with lower escape latency than rats fed a regular diet and maintained under sedentary conditions (RD/Sed). Exercise can boost the effect of DHA showing lower latency (DHA/Exc) to find the platform compared with DHA-enriched diet-fed rats (DHA/Sed) or exercised rats fed a RD. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01. (B) DHA and exercise elevate levels of Bdnf in the hippocampus of rats, and the combination of exercise and DHA had a synergistic effect. The values are expressed as percent of RD-Sed group (mean S.E.M.). ∗p < 0.05.

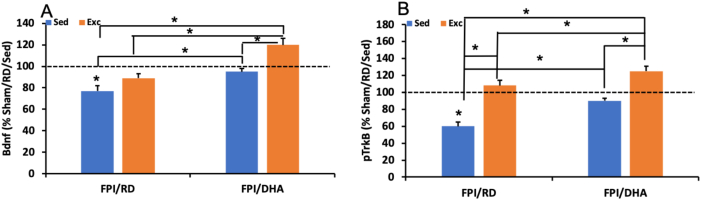

Fig. 3.

Exercise and DHA supplementation mitigated a reduction in hippocampal levels of Bdnf (A) and p-TrkB (B) after FPI. The combination of DHA and exercise had a synergistic effect. ∗p < 0.05. FPI, fluid percussion injury; Sed, sedentary; Exc, exercise.

Exercise also seems to influence DHA function by normalizing DHA content in the brain, a process that appears to be mediated through enzymes that control the metabolism of DHA in the membrane.33,38,39 The collaborative action of exercise and DHA has been shown to be also instrumental to compensate for the reduction in the levels of BDNF and the activation of the BDNF receptor p-TrkB, and for protecting against decay in the spatial learning ability after TBI (Fig. 3).39 These findings suggest that the combined actions of exercise and DHA supplementation have strong therapeutic potential for reducing the deleterious effects of TBI on membrane homeostasis, synaptic plasticity, and cognition. Although the separate applications of exercise or DHA supplementation were sufficient to counteract the TBI-related reductions of Acox1 and 17 -HSD4, exercise boosted the effects of DHA on Acox1. The effects of exercise or diet were also sufficient to counteract the reduction of iPLA2 after TBI while the combined actions of DHA and exercise produced a greater elevation of iPLA2.33 The combined applications of the DHA diet and exercise were more effective than the separate applications of DHA and exercise on the spatial learning ability after TBI. The overall evidence suggests that increased levels of BDNF under the actions of DHA and exercise may serve to support cognition and synaptic plasticity. Our previous study demonstrated that a combination of DHA and exercise can potentiate the cognition and BDNF-related plasticity in intact rats.33,38,39

Conclusion

Abundant evidence points to the power of physical activity to promote the overall health of the brain and body throughout the lifespan. In particular, exercise has been shown to be an effective therapy to normalize weaknesses associated with neurological disorders such as traumatic brain injury (TBI). The fact that TBI is associated with an early period of metabolic dysfunction, complicates the action of exercise as this also consumes metabolic energy. Therefore, there is a need to find ways to boost the action of exercise when it is mostly needed such as during the acute period of TBI. BDNF has been shown to be an important molecular mediator for the action of exercise on brain plasticity and function. Although BDNF possesses the unique ability to support synaptic plasticity and transmission of information across nerve cells through, the poor pharmacokinetic profile of BDNF has limited its therapeutic applicability. The flavonoid derivative, 7,8-dihydroxyflavone (7,8-DHF), signals through the same TrkB receptors used by BDNF and results in activation of downstream BDNF signaling pathways. The pharmacokinetic limitations of BDNF are avoided by the use of 7,8-DHF, which makes it a promising pharmacological agent for supporting activity-based rehabilitation during the acute post-injury period after TBI. Indeed, compelling evidence points to the possibility to normalize brain metabolism during the early post-injury convalescence period to support functional plasticity and prevent long-term functional deficits. In turn, the omega 3 fatty acid DHA offers another possibility to support the action of BDNF-mediated plasticity related to the action of exercise. DHA is abundant in the phospholipid composition of plasma membranes in the brain and its action is important for brain development and plasticity. DHA is a major modulator of synaptic membrane fluidity and function, which is fundamental for supporting cell signaling and synaptic plasticity. Exercise influences DHA function by normalizing DHA content in the brain, such that the collaborative action of exercise and DHA can be instrumental to boost BDNF function with strong therapeutic potential for reducing the deleterious effects of TBI on membrane homeostasis, synaptic plasticity, and cognition. Even further, based on reports about the separate beneficial actions of 7,8-DHF and DHA on the pathology of TBI, it is highly possible that both of these components can have an additional benefit when both are combined together. Given the intrinsic potential of exercise to promote health in the brain and body after brain injury, further studies to determine the potential synergistic actions of exercise, 7,8-DHF and DHA may prove highly relevant.

Submission statement

This work has not been submitted for publication elsewhere and all the authors listed have approved the manuscript enclosed.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed to write the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that do not have conflicts of interest relevant to this review.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers: NS111378; NS117148; NS050465; NS116838).

References

- 1.Lo J, Chan L, Flynn S. A systematic review of the incidence, prevalence, costs, and activity and work limitations of amputation, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, back pain, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, stroke, and traumatic brain injury in the United States: a 2019 update. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102(1):115–131. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearn ML, Niesman IR, Egawa J, et al. Pathophysiology associated with traumatic brain injury: current treatments and potential novel therapeutics. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2017;37(4):571–585. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0400-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vella MA, Crandall ML, Patel MB. Acute management of traumatic brain injury. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97(5):1015–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galgano M, Toshkezi G, Qiu X, Russell T, Chin L, Zhao LR. Traumatic brain injury: current treatment strategies and future endeavors. Cell Transplant. 2017;26(7):1118–1130. doi: 10.1177/0963689717714102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucke-Wold BP, Logsdon AF, Nguyen L, et al. Supplements, nutrition, and alternative therapies for the treatment of traumatic brain injury. Nutr Neurosci. 2018;21(2):79–91. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2016.1236174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaynman S, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Hippocampal BDNF mediates the efficacy of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20(10):2580–2590. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang CS, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. BDNF signaling in context: from synaptic regulation to psychiatric disorders. Cell. 2022;185(1):62–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lista I, Sorrentino G. Biological mechanisms of physical activity in preventing cognitive decline. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30(4):493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9488-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC. Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(6):295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):3017–3022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Praag H, Christie BR, Sejnowski TJ, Gage FH. Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(23):13427–13431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez-Pinilla F, Hillman C. The influence of exercise on cognitive abilities. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(1):403–428. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colcombe SJ, Kramer AF, McAuley E, Erickson KI, Scalf P. Neurocognitive aging and cardiovascular fitness: recent findings and future directions. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;24(1):9–14. doi: 10.1385/JMN:24:1:009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassilhas RC, Viana VA, Grassmann V, et al. The impact of resistance exercise on the cognitive function of the elderly. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1401–1407. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318060111f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yaffe K, Fiocco AJ, Lindquist K, et al. Predictors of maintaining cognitive function in older adults: the Health ABC study. Neurology. 2009;72(23):2029–2035. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a92c36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heyn PC, Johnson KE, Kramer AF. Endurance and strength training outcomes on cognitively impaired and cognitively intact older adults: a meta-analysis. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(6):401–409. doi: 10.1007/BF02982674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sibley BA, Etnier JL. The relationship between physical activity and cognition in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2003;15(3):243–256. doi: 10.1123/pes.15.3.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rethorst CD, Trivedi MH. Evidence-based recommendations for the prescription of exercise for major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(3):204–212. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000430504.16952.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grealy MA, Johnson DA, Rushton SK. Improving cognitive function after brain injury: the use of exercise and virtual reality. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(6):661–667. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griesbach GS, Hovda DA, Molteni R, Wu A, Gomez-Pinilla F. Voluntary exercise following traumatic brain injury: brain-derived neurotrophic factor upregulation and recovery of function. Neuroscience. 2004;125(1):129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chin LM, Keyser RE, Dsurney J, Chan L. Improved cognitive performance following aerobic exercise training in people with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(4):754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Praag H. Neurogenesis and exercise: past and future directions. NeuroMolecular Med. 2008;10(2):128–140. doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(3):266–270. doi: 10.1038/6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Huang Z, Xia H, Xiong J, Ma X, Liu C. The benefits of exercise for outcome improvement following traumatic brain injury: evidence, pitfalls and future perspectives. Exp Neurol. 2022;349:113958. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griesbach GS, Gomez-Pinilla F, Hovda DA. Time window for voluntary exercise-induced increases in hippocampal neuroplasticity molecules after traumatic brain injury is severity dependent. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(7):1161–1171. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agrawal R, Tyagi E, Vergnes L, Reue K, Gomez-Pinilla F. Coupling energy homeostasis with a mechanism to support plasticity in brain trauma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842(4):535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C, Wang Z, Zhang Z, et al. The prodrug of 7,8-dihydroxyflavone development and therapeutic efficacy for treating Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(3):578–583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718683115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J, Chua KW, Chua CC, et al. Antioxidant activity of 7,8-dihydroxyflavone provides neuroprotection against glutamate-induced toxicity. Neurosci Lett. 2011;499(3):181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang SW, Liu X, Yepes M, et al. A selective TrkB agonist with potent neurotrophic activities by 7,8-dihydroxyflavone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(6):2687–2692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913572107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal R, Noble E, Tyagi E, Zhuang Y, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Flavonoid derivative 7,8-DHF attenuates TBI pathology via TrkB activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(5):862–872. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishna G, Agrawal R, Zhuang Y, et al. 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone facilitates the action exercise to restore plasticity and functionality: implications for early brain trauma recovery. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863(6):1204–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bigford GE, Alonso OF, Dietrich D, Keane RW. A novel protein complex in membrane rafts linking the NR2B glutamate receptor and autophagy is disrupted following traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(5):703–720. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chytrova G, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Exercise contributes to the effects of DHA dietary supplementation by acting on membrane-related synaptic systems. Brain Res. 2010;1341:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biegon A. Cannabinoids as neuroprotective agents in traumatic brain injury. Curr Pharmaceut Des. 2004;10(18):2177–2183. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ansari MA, Roberts KN, Scheff SW. Oxidative stress and modification of synaptic proteins in hippocampus after traumatic brain injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(4):443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stillwell W, Shaikh SR, Zerouga M, Siddiqui R, Wassall SR. Docosahexaenoic acid affects cell signaling by altering lipid rafts. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2005;45(5):559–579. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2005046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calder PC, Yaqoob P. Understanding omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(6):148–157. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu A, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Docosahexaenoic acid dietary supplementation enhances the effects of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Neuroscience. 2008;155(3):751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu A, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Exercise facilitates the action of dietary DHA on functional recovery after brain trauma. Neuroscience. 2013;248:655–663. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]