Abstract

This study investigated how children's 24-hour (24-h) movement behaviours were affected by SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Previous research examined 24-h movement behaviours in Saudi Arabia seven months after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. This repeat cross-sectional study examined changes in 24-h movement behaviours 12 months after the WHO declaration. The Time 2 survey repeated five months (1 March – 15 May 2021) after Time 1 survey (1 October – 11 November 2020). The survey was distributed to parents of children aged 6–12 years across Saudi Arabia via an online survey. Children were classified as meeting 24-h movement guidelines if they reported uninterrupted sleep for 9–11 h per night, ≤ 2 h of recreational sedentary screen time (RST) per day and ≥ 60 min of moderate-to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) per day. A total of 1 045 parents from all regions of Saudi Arabia responded (42.4%). Only 1.8% of children met all components of the guidelines, compared to 3.4% in Time 1. In the present study, girls spent more days per week in MVPA ≥ 60 min duration than boys (3.0 vs 2.6; p = 0.025), while boys had spent more days per week engaged in activities that strengthened muscle and bone than girls (3.0 vs 2.8; p = 0.019). Healthy levels of physical activity (PA), sedentary behaviour (SB) and sleep further declined in Saudi children five months after the Time 1 survey. These challenges require urgent intervention to ensure children's movement behaviours improve as Saudi Arabia moves out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Sleep, Sedentary behaviour, Physical activity, Children, COVID-19

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

SARS-CoV-2

- M

Mean

- MVPA

Moderate-to Vigorous-Intensity Physical Activity

- N

Number

- P

Probability

- PA

Physical Activity

- RST

Recreational Sedentary Screen Time

- SAR

Saudi Riyal

- SB

Sedentary Behaviour

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SPSS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- ST

Screen Time

- TV

Television

- US

United States

- VG

Video Games

- WHO

World Health Organization

- PE

Physical Education

- 24-h

24-hour

Introduction

One of the health consequences of lockdowns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has been on the movement behaviours of school-aged children.1 In this paper, movement behaviours refer to physical activity (PA), sedentary behaviour (SB) – including screen time (ST) and sleep.2 Globally, many countries enforced restrictions that resulted in school-aged children not attending school, with classes delivered remotely.3 A systematic review4 that included six studies from Australia, Croatia, China, Canada, Latin America (Brazil, Chile, Colombia), and Europe (Italy and Spain) investigated changes in PA and SB from before to during the COVID-19 lockdown. These studies reported a decrease in children's PA levels, and five studies reported increases in SB. A subsequent study from Spain showed similar results.5 We conducted an initial study in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia6 which investigated the impact of COVID-19 on children's 24-hour (24-h) movement behaviours early in the pandemic, using the World Health Organization (WHO), Australian and Canadian guidelines (as no Saudi 24-h movement guidelines currently exist).2,7,8 We found that children's PA levels declined, they slept more, and their use of electronic screen devices significantly increased. To date, only two studies have examined the changes in movement behaviours at two time points during COVID-19 and both reported decreases in PA levels and increases in SB at Time 2 compared to Time 1.9,10 Neither of these two studies were from the Eastern Mediterranean region, a region where there has been a noticeable gap in the literature. We hypothesize that COVID-19 has a negative impact on Saudi children's 24-h movement behaviours. The purpose of this study was to investigate the five-month changes in movement behaviours among children in Saudi Arabia, at a time when there were governmental restrictions.

Methods

The methods of this study were identical to those reported in the previous (Time 1) study.6 This repeat cross-sectional study (Time 2) collected data between March and May 2021. The survey was promoted across all 13 regions of Saudi Arabia through the Education Policy Research Centre at the Saudi Ministry of Education in Riyadh to all elementary schools as well as on social media (Twitter and WhatsApp). Approval was obtained from the Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia (2639/2021) and the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Wollongong, Australia (HE288/2021).

For the survey to be submitted parents were required to complete all of the survey questions. The Time 1 survey6 was conducted between October and November 2020 in autumn (temperatures ranged between 24 °C [75 °F] and + 40 °C [104 °F] in September, and between 14 °C [57 °F] and + 27 °C [81 °F] in November), and during school days (remotely delivered classes online), with governmental restrictions due to COVID-19, which resulted in schools suspended. The Time 2 survey was conducted during spring (temperature ranged from + 14.5 °C [58 °F] to + 28 °C [83 °F] in March, and from + 24 °C [75 °F] to + 39 °C [102 °F] in May) and during school days (remotely delivered classes) with similar governmental restrictions. During Time 2, there was a 20-day school holiday period. During the remotely delivered classes period in Time 1 and Time 2, there were no active physical education (PE) classes online. Schooling started at 3:30 p.m. (remotely) and ended at 7 p.m.

Data collection

Parents of healthy children aged between 6 and 12 years who were living in Saudi Arabia were invited to participate in the study. A link to an online survey in Arabic, using the Qualtrics platform, was provided to parents. The survey was designed to take approximately 10 min to complete and consisted of three parts: parental and child demographics, child's current movement behaviours, and changes in child's movement behaviours as a result of COVID-19. Before answering the survey, parents were provided with an online parent information sheet and consent form as the first page of the survey. Parents were asked to complete a separate survey if they had more than one child (aged 6–12 years).

Survey

The survey was based on two previous surveys: a parental survey of young children's movement during COVID-1911 and the Children and Youth Movement and Play Behaviours Survey.12 It was translated into Arabic and back-translated into English to ensure the appropriateness of the questions.

Child and parent data including birth, sex, region of residence, parental education, and income were assessed using standard questions.11 Children's sleep duration, PA duration, and SB were proxy-reported by parents. Using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “a lot worse” (score = 1) to “a lot better” (score = 5), parents reported the balance of their children's overall healthy movement behaviours compared to before the COVID-19 outbreak.

Sleep quality was measured on a scale of 1–7, with 1 indicating “very difficult to settle to sleep” and 7 indicating “settles and drifts off to sleep within a few minutes”.

Children were classified as meeting the recommendation of the WHO, Australian and Canadian guidelines, if they reported uninterrupted sleep for 9–11 h per night, meeting the SB recommendation if they reported no more than 2 h of recreational sedentary screen time (RST) per day and meeting the PA recommendation if they reported ≥ 60 min of moderate-to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) per day.2,7,8 Selected items that were used in the current study are listed in Appendix A (the full survey is available in Appendix B).

Statistical analyses

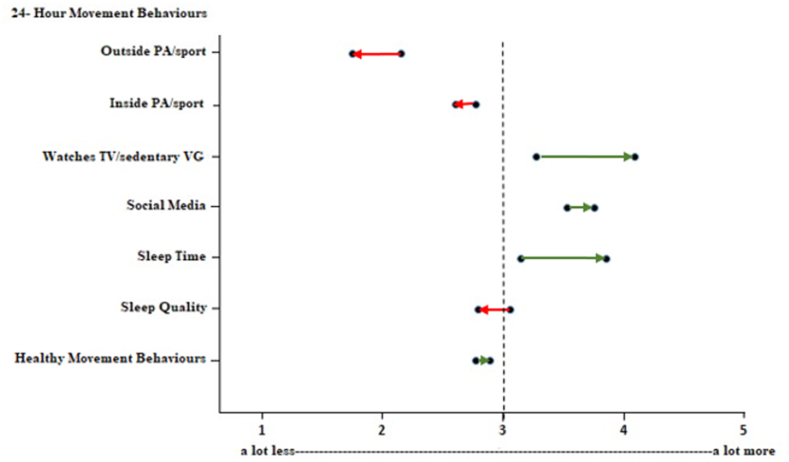

Statistical analyses were carried out in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 28, Chicago, IL, USA). Sample characteristics were summarized using means and standard deviations (SD) for all variables and the percentage of children meeting the 24-h movement guidelines.2,7,8 Gender differences in time spent in PA, SB, and sleep and in using social media were analysed using an independent samples t-test. A forest plot was used to present the parent-reported changes in 24-h movement behaviours of the children during the first (October to November, 2020) and the second time (March to May, 2021) of the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Parents and children characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographics of the parents who responded to the survey. Of those parents who expressed an interest (n = 2 464), 1 045 completed the survey (42.4%). Of these, 88.6% were Saudis and 11.4% were non-Saudis. The respondents included 587 mothers (56.2%) with an average age of 42.6 (± 9.2) years. The mean age of the children was 8.7 (± 1.9) years. Fifty-one percent of the study sample were girls. The parents’ average monthly income was $4 355. Most parents had bachelor's adegree (47%). Just under half of the sample of children were boys (49.2%). Compared with the Saudi population, our sample comprised more females, was slightly older, and had a similar monthly income and education level.13, 14, 15

Table 1.

Parent and child characteristics at Time 2 (n = 1 045).

| Study sample | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), M (SD) | 42.6 (9.2) | |

| Parent/caregiver's relationship to the child participating in the study, n (%) | Mother | 587 (56.2) |

| Father | 458 (43.8) | |

| Nationality, n (%) | Saudi | 926 (88.6) |

| Non-Saudi | 119 (11.4) | |

| Education level, n (%) | Primary school | 43 (4.1) |

| High school | 220 (21) | |

| Diploma | 97(9.4) | |

| Bachelor's degree | 491 (47) | |

| Master's degree | 133 (12.7) | |

| PhD | 61 (5.8) | |

| Living region, n (%) | Al-Riyadh | 334 (32) |

| Al-Jouf | 39 (3.7) | |

| Al-Qassim | 36 (3.4) | |

| Al-Bahah | 16 (1.7) | |

| Asir | 44 (4.2) | |

| Eastern Province | 124 (11.8) | |

| Hail | 26 (2.4) | |

| Jazan | 14 (1.3) | |

| Mecca | 308 (29.6) | |

| Medina | 39 (3.7) | |

| Northern Borders | 21 (2) | |

| Najran | 13 (1.2) | |

| Tabuk | 31 (3) | |

| Monthly income (SAR), n (%) | 0–3 000 | 137 (13.3) |

| 3 000–7 000 | 107 (10.2) | |

| 7 000-10 000 | 135 (12.9) | |

| 10 000–15 000 | 320 (30.6) | |

| 15 000–20 000 | 238 (22.7) | |

| 20 000+ | 108 (10.3) | |

| Child demographic profile | ||

| Age (years), M (SD) | 8.7 (1.9) | |

| Gender, n (%) | Boys | 514 (49.2) |

| Girls | 531 (50.8) | |

M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, SAR = Saudi Riyal, n = number.

Children's current behaviours and changes in behaviours during COVID-19

Table 2 reports time spent on movement behaviours and the proportion of children meeting the guidelines during the COVID-19 outbreak in Saudi Arabia. Girls spent significantly more days/week in MVPA ≥ 60 min than boys (p = 0.025); however, boys spent more days in activities that strengthened their muscles and bones (p = 0.019). For the remainder of the behaviours (sleep duration and quality; ST and playing outside), there were no significant differences between boys and girls.

Table 2.

Comparison of five-months changes in children's movement behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak.

| Total sample |

Girls |

Boys |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct 2020 (n = 1 021) | Mar 2021 (n = 1 045) | p value | Oct 2020 (n = 616) | Mar 2021 (n = 531) | p value | Oct 2020 (n = 405) | Mar 2021 (n = 514) | p value | |

| Children's movement behaviors, M (SD) | |||||||||

| MVPA ≥ 60 min (days/week) | 4.52 (2.40) | 2.77 (2.67) | <0.0001 | 4.51 (2.40) | 2.95 (2.69) | <0.0001 | 4.54 (2.41) | 2.58 (2.67) | <0.0001 |

| Activities to strengthen muscles and bones (days/week) | 2.59 (2.37) | 2.89 (1.96) | <0.0001 | 2.52 (2.34) | 2.75 (2.05) | 0.08 | 2.70 (2.42) | 3.03 (1.85) | 0.21 |

| Sleep (h/day) | 9.68 (2.26) | 11.28 (2.22) | <0.0001 | 9.76 (2.42) | 11.30 (2.15) | <0.0001 | 9.55 (1.99) | 11.25 (2.28) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep quality | 5.40 (1.99) | 5.39 (1.82) | 0.93 | 5.38 (2.05) | 5.46 (1.85) | 0.51 | 5.43 (1.91) | 5.33 (1.78) | 0.40 |

| ST ≤ 2 h (days/week) | 5.39 (2.19) | 4.95 (1.89) | <0.0001 | 5.26 (2.21) | 4.84 (1.97) | <0.0001 | 5.60 (2.15) | 5.06 (1.80) | <0.0001 |

| Playing outside (h/day) |

2.19 (1.34) |

1.57 (1.03) |

<0.0001 |

2.15 (1.33) |

1.62 (1.11) |

<0.0001 |

2.26 (1.36) |

1.52 (0.93) |

<0.0001 |

| Proportion of children meeting the WHO/Australian/Canadian guidelines (%) | |||||||||

| MVPA | 35.7 | 18.2 | <0.0001 | 32.6 | 19.8 | <0.0001 | 35.1 | 16.5 | <0.0001 |

| ST | 15.2 | 12.8 | <0.0001 | 16.6 | 14.3 | 0.001 | 13.1 | 11.3 | <0.0001 |

| Sleep | 56.9 | 26.8 | <0.0001 | 55.6 | 24.3 | <0.0001 | 58.8 | 29.4 | <0.0001 |

| 24-h combined |

3.4 |

1.8 |

<0.0001 |

3.57 |

2.1 |

<0.0001 |

2.47 |

1.6 |

<0.0001 |

| Five-months changes in children's movement behaviours during COVID-19 outbreak, M (SD) | |||||||||

| PA or sport outside | 2.16 (1.27) | 1.76 (1.16) | <0.0001 | 2.19 (1.22) | 1.75 (1.12) | <0.0001 | 2.11 (1.34) | 1.78 (1.20) | <0.0001 |

| PA or sport inside | 2.78 (1.26) | 2.61 (1.06) | <0.0001 | 2.85 (1.26) | 2.54 (1.07) | <0.0001 | 2.68 (1.23) | 2.68 (1.04) | <0.0001 |

| Watches TV or sedentary VG | 3.28 (1.23) | 4.10 (1.26) | <0.0001 | 3.49 (1.26) | 4.03 (1.30) | <0.0001 | 2.72 (1.18) | 4.18 (1.22) | <0.0001 |

| Uses social media | 3.54 (1.87) | 3.76 (1.31) | <0.0001 | 4.08 (1.85) | 3.73 (1.34) | <0.0001 | 2.60 (1.90) | 3.80 (1.27) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep quantity | 3.15 (0.94) | 3.86 (1.10) | <0.0001 | 3.17 (0.96) | 3.79 (1.15) | <0.0001 | 3.12 (0.91) | 3.93 (1.04) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep quality | 3.06 (0.95) | 2.80 (0.93) | <0.0001 | 3.07 (0.96) | 2.84 (0.97) | <0.0001 | 3.04 (0.93) | 2.77 (0.89) | <0.0001 |

| Overall healthy movement behaviours | 2.78 (1.03) | 2.90 (0.83) | 0.01 | 2.83 (1.02) | 2.91 (0.89) | 0.14 | 2.71 (1.04) | 2.88 (0.77) | 0.01 |

n = number, p = probability, MVPA = Moderate-to Vigorous-Intensity Physical Activity, ST = Screen Time, 24-h = 24-hour, WHO = World Health Organization, COVID-19 = SARS-CoV-2, M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, PA = Physical Activity, TV = Television, VG = Video games.

Regarding the proportion of children meeting the 24-h movement guidelines,2,7,8 only 1.8% met all three of the 24-h movement behaviour recommendations. When examining the behaviours separately, 26.8% of children met the sleep guidelines, 18.2% met the PA recommendation and 12.8% met the SB recommendation. The proportion of girls who met the PA and RST recommendations was significantly higher than boys (p < 0.000 1, 0.001, respectively). However, more boys met the sleep recommendation (p = 0.048).

Table 2 also reported parent perceived changes in their child's movement behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak. Children's perceived combined indoor PA and sport significantly decreased compared to before the COVID-19 outbreak (an average of 2.61 points (a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “a lot worse” [score = 1] to “a lot better” [score = 5]) out of 5.0, p = 0.037). Boys were perceived to have significantly more sleeping time than girls (average of 3.93 vs 3.79 points out of 5.0, p = 0.041). Notably, 70% of children had an electronic screen device in their bedroom.

New ways families are approaching movement behaviours

Parents were asked if there was an inside leisure activity or hobby that their child was doing a lot more during the COVID-19 outbreak, and 22.8% of parents answered yes. These included drawing (25%), playing soccer (18.2%), playing Intelligence Quotient games (21.3%), playing ping pong (11%), playing chess (9.2%), playing in the backyard (8.2%), doing handcrafts (2.9%), reading (2.1%), and learning new languages (2.1%). Only 11% of parents indicated their child was involved in a lot more outside leisure activity or hobbies during the COVID-19 outbreak. These included playing soccer (29%), hiking (26.7%), running or walking (24.2%), martial arts (6.1%), biking (4.9%), playing archery (4.6%), and swimming (4.5%).

Comparison between Time 1 and Time 2 during the COVID-19 outbreak

Table 2 compared the results from Time 1 to Time 2 in terms of how movement behaviours have been affected by COVID-19 among Saudi children. For the entire sample, there were significant differences between Time 1 and Time 2, for all considered variables (p < 0.000 1), except for sleep quality. These differences showed a decrease in children's MVPA and playing outside, and an increase in activities to strengthen muscles and bones, ST, and sleep duration. The analysis of the results for girls and boys separately was in line with the total sample results, with the exception of activities to strengthen muscles and bones, where there was not a significant change for boys. The proportion of the total sample (boys and girls) meeting the MVPA, RST, sleep, and the 24-h combined guidelines significantly decreased (p < 0.000 1) in Time 2 compared to Time 1.

As seen in Fig. 1, parents perceived changes in children's movement behaviours from Time 1 to Time 2 significantly decreased (p < 0.000 1), including children's outside and inside PA and sport and sleep quality, while sleep duration, watching television (TV) or playing sedentary video games, and the use of social media significantly increased (p < 0.000 1).

Fig. 1.

Parent-reported changes in 24-h movement behaviours in Saudi children (6–12 years) during the first (October 2020) and second time (March 2021) of the COVID-19 pandemic. Scores are based on a 5-point scale ranging from “a lot less” (score 1) to “about the same” (score 3) to “a lot more” (score 5). Green arrows represent when October 2020 (Time 1) scores ranked less compared with March 2021 (Time 2) within the same variable. Red arrows represent when October 2020 (Time 1) scores ranked higher compared with March, 2021 (Time 2) within the same variable. PA = physical activity. VG = video games.

Discussion

The findings of this study confirmed our hypothesis that COVID-19 has a negative impact on Saudi children's 24-h movement behaviours. This repeated cross-sectional study assessed the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on movement behaviours of Saudi children during the period March to May, 2021, compared with our initial results from October to November, 2020. The results showed that only 1.8% of children (1.6% of boys and 2.1% of girls) met all recommendations of the 24-h movement guidelines. Twenty-seven percent of children met the sleep recommendation, 18.2% met the PA recommendation and 12.8% met the SB recommendation compared to Time 1 where 57% met the sleep recommendation, 35.7% met the PA recommendation and 15.2% met the SB recommendation.

The results of the comparison between Time 1 and Time 2 showed that COVID-19 had a significant impact and affected children's movement behaviours negatively within a short period of time. The percentage of children meeting the combined 24-h movement guidelines in Time 2 decreased significantly when compared to Time 1. Our findings are consistent with the results of a Canadian study9 which reported a decrease in the proportion of children who met movement guidelines in Time 2 (4.5%) compared to Time 1 (4.8%) due to the impact of COVID-19. However, our results showed that the percentage of girls who met movement guidelines was higher than of boys (2.1% vs 1.6%). Our findings are also consistent with the results from nine European countries10 which showed that 9.3% of children met the WHO PA recommendation in Time 2 compared to 19% in Time 1, while the proportion of children who did not meet RST recommendation was high in both phases (60.6% [weekdays] and 47.7% [weekend days] in Time 2 compared to 69.5% [weekdays] and 64% [weekend days] in Time 1).

These results were somewhat expected as tighter government restrictions were introduced over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic which further limited children's opportunities to play outdoors,15 which has been shown to be positively associated with children's PA levels.17

School closures could be another reason for the decrease in children's PA levels, as children, in general, were more physically active at school pre-COVID-19.12 A study involving 785 Canadian children (10.57 ± 0.7 years)18 and a systematic review of 68 studies19 showed that not walking to school was associated with a decrease in PA levels. Furthermore, as there were no active PE classes online, this may have contributed to a further reduction in children's PA levels. A European study showed that 57% of children who were active during online PE classes during the COVID-19 outbreak met the WHO PA recommendations.16

The sleep patterns of children in the current study have been affected by policy changes as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. To ensure working parents could assist children in their schooling, the Saudi Ministry of Education mandated that schooling started at 3:30 p.m. (online) and ended at 7p.m. These changes to daily routines may also have affected the time that children went to sleep. In addition, the absence of a structured day time schedule could have further hindered opportunities to meet ST and PA recommendations, as shown in a study conducted on 8 395 children from 10 European countries.16

In the present study, school-aged children had a school holiday for 20 days during Time 2, which may have negatively impacted their movement behaviours.20 A study investigated the changes in sleep and PA of 154 United States (US) school-aged children (5–9 years) showed that a 1-week holiday had a negative impact on sleep, while a 3-week holiday had more increase in children's SB (33 min) and decrease in MVPA (12 min) per day.21 The structured days hypothesis indicates that during the unstructured days (e.g. school holidays), children's sleep, SB, and PA are less regulated compared to structured days (e.g. school days),19 therefore, there might be fewer opportunities for children to meet the 24-h movement guidelines during school holidays. This could be another reason that may explain the decline in children's movement behaviours.

The number of children in this study who had an electronic screen device in their bedroom increased from Time 1 (40%) to Time 2 (70%). This may explain the decrease in the proportion of children meeting the ST recommendation, as having these electronic screen devices in children's bedrooms negatively affects their sleep quality and duration.22 Our numbers align with what was reported in a study from the US which indicated that 75% of US children, aged 6–17 years (mean age: 11.4), had an electronic screen device in their bedroom.23 The authors reported that 90% of children had insufficient sleep time and that having household rules and regular sleep-wake routines may encourage children to have better sleep.23

As the data of this repeated cross-sectional study were from all the 13 regions of Saudi Arabia, there may be some differences and disparities between urban and rural areas in meeting the recommendations of movement behaviours due to the level of government restrictions and COVID-19 infections in each region. In addition, there are differences in the climate of the 13 regions in Saudi Arabia due to its large area. The climate is moderate in the west and the southwestern areas, hot in the interior areas, and hot and humid in the coastal areas.24 These differences in the weather may play an important role in meeting 24-h movement guidelines as reported in a study that examined the relationship between climate indicators and daily detected COVID-19 cases in Saudi Arabia which showed a positive association between the spread of COVID-19 and temperature among the top Saudi cities (Riyadh, Jeddah, Makkah, Madinah, and Dammam) affected by COVID-19.25

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first known from an Arabian country to provide data on school-aged children's 24-h movement behaviour at two points of time during the COVID-19 outbreak. Moreover, this study provided data across all the 13 regions of Saudi Arabia since there is no nationally representative data of 24-h movement behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak. A limitation of the study is that movement behaviours were assessed via a parent survey as collecting data using device-based measures on a large sample was not possible due to the COVID-19 restrictions. As the data were anonymous, the differences from Time 1 to Time 2 could be due to differences in the samples, in addition to COVID-19.

Conclusion

This follow-up study provided evidence of the impact of the COVID-19 restrictions on Saudi children's movement behaviours and investigated the changes in these behaviours over the two time periods during the COVID-19 restrictions. Due to the difference in the COVID-19 infection rate in several regions of Saudi Arabia, it is recommended for future studies to be conducted by region. As no Saudi 24-h movement guidelines currently exist, we recommend the development of such guidelines for children in Saudi Arabia as they have significant public health benefits. The findings of this study contribute to supporting the efforts to mitigate the negative impact of this pandemic, as part of the response strategies, and for future pandemics.

Submission statement

All authors have read and agree with manuscript content and while this manuscript is being reviewed for this journal, the manuscript will not be submitted elsewhere for review and publication.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, Y.A.A., A.-M.P. and A.D.O.; methodology, Y.A.A., A.-M.P. and A.D.O.; data collection and management, Y.A.A., formal analysis, Y.A.A., writing—original draft preparation, Y.A.A.; writing—review and editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from the Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia (2639/2021) and the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Wollongong, Australia (HE288/2021). This survey collected data between March and May, 2021. A link to an online survey in Arabic, using the Qualtrics platform, was provided to parents. Before answering the survey, parents were provided with an online parent information sheet and consent form as the first page of the survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the parents and their children whose support and collaboration made this study possible. YA is supported by King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. ADO is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Investigator Grant (APP1176858).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smhs.2022.05.001.

Contributor Information

Yazeed A. Alanazi, Email: yana918@uowmail.edu.au.

Anthony D. Okely, Email: tokely@uow.edu.au.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.López-Gil J.F., Tremblay M.S., Brazo-Sayavera J. Changes in healthy behaviors and meeting 24-h movement guidelines in Spanish and Brazilian preschoolers, children and adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown. Children. 2021;8(2):83. doi: 10.3390/children8020083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okely A.D., Ghersi D., Loughran S.P., Cliff D.P., Shilton T., Jones R.A. 2019. Australian 24-hour movement guidelines for children (5-12 years) and young people (13-17 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour.https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian-24-hour-movement-guidelines-for-children-5-to-12-years-and-young-people-13-to-17-years-an-integration-of-physical-activity-sedentary-behaviour-and-sleep Accessed April 21, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ECLAC-UNESCO . 2020. Education in the time of COVID-19.https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/45905/1/S2000509_en.pdf Accessed April 21, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stockwell S., Trott M., Tully M., et al. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2021;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medrano M., Cadenas-Sanchez C., Oses M., Arenaza L., Amasene M., Labayen I. Changes in lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 confinement in Spanish children: a longitudinal analysis from the MUGI project. Pediatr Obes. 2021;16(4):1–11. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alanazi Y.A., Parrish A.-M., Okely A.D. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on 24-hour movement behaviours among children in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional survey. Child Care Health Dev. 2022 doi: 10.1111/cch.12999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tremblay M.S., Carson V., Chaput J.-P., et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metabol. 2016;41(6):S311–S327. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bull F.C., Al-Ansari S.S., Biddle S., et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore S.A., Faulkner G., Rhodes R.E., et al. Few Canadian children and youth were meeting the 24-hour movement behaviour guidelines 6-months into the COVID-19 pandemic: follow-up from a national study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metabol. 2021;46(10):1225–1240. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2021-0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovacs V.A., Brandes M., Suesse T., et al. Are we underestimating the impact of COVID-19 on children's physical activity in Europe?—a study of 24 302 children. Eur J Publ Health. 2022;32(3):494–496. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckac003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okely A.D., Kariippanon K.E., Guan H., et al. Global effect of COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep among 3- to 5-year-old children: a longitudinal study of 14 countries. BMC Publ Health. 2021;21(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10852-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore S.A., Faulkner G., Rhodes R.E., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: a national survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2020;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00987-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.General Authority for Statistics Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Labor Force. General Authority for Statistics. 2017 https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/814 Accessed April 21, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 14.General Authority for Statistics Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Education and Training Survey 2017. General Authority for Statistics. 2017 https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/5656 Accessed April 21, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 15.General Authority for Statistics Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Household Income and Expend Survey 2018. General Authority for Statistics. 2018 https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/37 Accessed April 21, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs V.A., Starc G., Brandes M., et al. Physical activity, screen time and the COVID-19 school closures in Europe – an observational study in 10 countries. Eur J Sport Sci. 2022;22(7):1094–1103. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2021.1897166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee E.-Y., Bains A., Hunter S., et al. Systematic review of the correlates of outdoor play and time among children aged 3-12 years. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2021;18(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faulkner G., Stone M., Buliung R., Wong B., Mitra R. School travel and children's physical activity: a cross-sectional study examining the influence of distance. BMC Publ Health. 2013;13(1):1166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larouche R., Saunders T.J., John Faulkner G.E., Colley R., Tremblay M. Associations between active school transport and physical activity, body composition, and cardiovascular fitness: a systematic review of 68 studies. J Phys Activ Health. 2014;11(1):206–227. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2011-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weaver R.G., Armstrong B., Hunt E., et al. The impact of summer vacation on children's obesogenic behaviors and body mass index: a natural experiment. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2020;17(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01052-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver R.G., Beets M.W., Perry M., et al. Changes in children's sleep and physical activity during a 1-week versus a 3-week break from school: a natural experiment. Sleep. 2019;42(1):1–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hale L., Guan S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;21:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buxton O.M., Chang A.-M., Spilsbury J.C., Bos T., Emsellem H., Knutson K.L. Sleep in the modern family: protective family routines for child and adolescent sleep. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.General Authority for Statistics. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia . 2019. General Information about The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. General Authority for Statistics.https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/page/259 Accessed January 26, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdel-Aal M.A.M., Eltoukhy A.E.E., Nabhan M.A., AlDurgam M.M. Impact of climate indicators on the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;29(14):20449–20462. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17305-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.