Abstract

Two putative malate dehydrogenase genes, MJ1425 and MJ0490, from Methanococcus jannaschii and one from Methanothermus fervidus were cloned and overexpressed in Escherichia coli, and their gene products were tested for the ability to catalyze pyridine nucleotide-dependent oxidation and reduction reactions of the following α-hydroxy–α-keto acid pairs: (S)-sulfolactic acid and sulfopyruvic acid; (S)-α-hydroxyglutaric acid and α-ketoglutaric acid; (S)-lactic acid and pyruvic acid; and 1-hydroxy-1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid and 1-oxo-1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid. Each of these reactions is involved in the formation of coenzyme M, methanopterin, coenzyme F420, and methanofuran, respectively. Both the MJ1425-encoded enzyme and the MJ0490-encoded enzyme were found to function to different degrees as malate dehydrogenases, reducing oxalacetate to (S)-malate using either NADH or NADPH as a reductant. Both enzymes were found to use either NADH or NADPH to reduce sulfopyruvate to (S)-sulfolactate, but the Vmax/Km value for the reduction of sulfopyruvate by NADH using the MJ1425-encoded enzyme was 20 times greater than any other combination of enzymes and pyridine nucleotides. Both the M. fervidus and the MJ1425-encoded enzyme catalyzed the NAD+-dependent oxidation of (S)-sulfolactate to sulfopyruvate. The MJ1425-encoded enzyme also catalyzed the NADH-dependent reduction of α-ketoglutaric acid to (S)-hydroxyglutaric acid, a component of methanopterin. Neither of the enzymes reduced pyruvate to (S)-lactate, a component of coenzyme F420. Only the MJ1425-encoded enzyme was found to reduce 1-oxo-1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid, and this reduction occurred only to a small extent and produced an isomer of 1-hydroxy-1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid that is not involved in the biosynthesis of methanofuran c. We conclude that the MJ1425-encoded enzyme is likely to be involved in the biosynthesis of both coenzyme M and methanopterin.

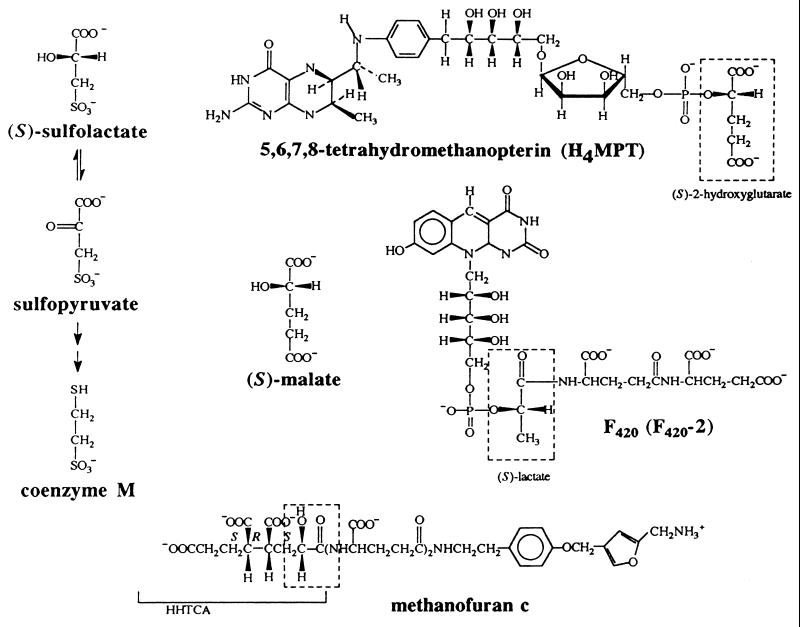

The biosynthesis of the methanogenic cofactors coenzyme M (2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid), methanopterin, coenzyme F420, and methanofuran c (Fig. 1) requires the generation of an α-hydroxy acid that either becomes a component in the final structure or serves as an intermediate in the formation of the coenzyme. In the case of coenzyme M, (S)-sulfolactate, formed from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and bisulfite, is an intermediate in the biosynthesis (28–30). In the case of methanopterin (24, 25) and several related modified folates (33, 34, 36), (S)-hydroxyglutaric acid (23) is incorporated into the coenzyme during its biosynthesis (32, 35). For coenzyme F420 (6) and its γ-polyglutamate derivatives (7, 8, 18), (S)-hydroxypropionic acid (S-lactic acid) becomes a part of the final structure. Finally, two (1R)-diastereomers of 1-hydroxy-1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid (HHTCA) serve as intermediates in the biosynthesis of the 1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid (HTCA) moiety of methanofuran (17; unpublished results), and another diastereomer of HHTCA [(1S)-HHTCA] is a component of methanofuran c (31). The HHTCA intermediates in HTCA biosynthesis have the same absolute stereochemistry at the α-hydroxy acid portion of the molecule as the pantothenic acid moiety of coenzyme A, the only other cofactor containing an α-hydroxy acid (10).

FIG. 1.

Methanogenic coenzymes that contain α-hydroxy acids as components of their structures. (S)-Sulfolactate is an intermediate in the biosynthesis of coenzyme M, and (S)-malate is an intermediate in the partial citric acid cycle.

At present, nothing is known about the enzymes required for the formation and the metabolism of these α-hydroxy acids and α-keto acids in the methanoarchaea. Based on the S-stereochemistry of the (S)-hydroxyglutaric acid present in methanopterin and the (S)-lactic acid present in coenzyme F420, it is likely that each is formed by the reduction of the corresponding α-keto acid by a NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenase related to the lactate/malate dehydrogenase group of enzymes (1, 3, 9). Likewise, it could be argued, again based on stereochemical grounds, that the oxidation of (S)-sulfolactate to sulfopyruvate occurring during the biosynthesis of coenzyme M could also be carried out by an enzyme related to the lactate/malate dehydrogenases.

Two malate dehydrogenases, designated MdhI and MdhII, were recently isolated from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum strain Marburg (22). Via the N-terminal sequences, the genes encoding the malate dehydrogenases would correspond to those encoded from the M. thermoautotrophicum (strain ΔH) genes MT1205 and MT0188, respectively (22). From genomic sequence data (21), the sequences of M. thermoautotrophicum genes MT1205 and MT0188 have 53.5 and 48.6% sequence identity, respectively, to the Methanococcus jannaschii genes MJ1425 and MJ0490 (2). In both of these organisms, these are the only two genes with any clear sequence homology to the lactate/malate family of dehydrogenases (2, 21). The M. jannaschii gene MJ0490, producing the MdhII enzyme, has 49% sequence identity to the (S)-lactate/malate dehydrogenases from bacteria and eukaryotes (1, 9), and it aligns well with the Archaeoglobus fulgidus AF0855-encoded malate dehydrogenase (16). From many sequence comparisons and site-directed mutagensis of members of this family of dehydrogenases, it could be shown that the structure of the amino acid at one conserved position can determine the substrate specificity and the coenzyme-binding specificity (9). A sequence comparison of the MJ0490 gene with those lactate/malate dehydrogenases would predict that the MJ0490 enzyme should prefer (S)-malate over (S)-lactate and NADP over NAD. The MJ1425-encoded enzyme, on the contrary, does not fit as well into the family of lactate/malate dehydrogenases. The MJ1425-encoded enzyme has 44% sequence identity with the malate dehydrogenases from the methanoarchaea Methanothermus fervidus (12) and the MTH1205-encoded enzyme mentioned above from M. thermoautotrophicum. The MJ1425-encoded enzyme has only 12% sequence identity to a malate dehydrogenase from Bacillus subtilis.

It is not clear why the M. jannaschii and M. thermoautotrophicum genomes contain two genes for malate dehydrogenases. Taking into account the lack of specificity of many of the known dehydrogenases (3, 15, 37), we considered it likely that one or more of these archaeal enzymes may be the enzyme(s) used for producing one or more of the (S)-α-hydroxy acids required for the biosynthesis of methanoarchaeal coenzymes.

To test these hypotheses, we have cloned and overexpressed the MJ0490 and MJ1425 genes from M. jannaschii and a malate dehydrogenase gene from M. fervidus in Escherichia coli and tested their protein products for the ability to reduce or oxidize desired coenzyme biosynthetic intermediates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of substrates.

The S and R stereoisomers of sulfolactate were prepared by nitrous acid deamination of (S)-cysteic acid and (R)-cysteic acid (M. Graupner and R. H. White, unpublished results). Sulfopyruvate was prepared as previously described (29). 1-Oxo-1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid (KHTCA) was prepared by the condensation of the dimethylketal derivative of α-ketoglutarate with the dimethyl ester of α-bromoglutaric acid (Graupner and White, unpublished results). The compound used as substrate consisted of a racemic mixture of one part of erythro-KHTCA and two parts of threo-KHTCA. Oxalacetate, pyruvate, (S)-lactate, (S)-2-hydroxyglutaric acid, and (R)-2-hydroxyglutaric acid were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co.

Identification, cloning, and high-level expression of the gene product.

Expression of MJ1425 and MJ0490 genes in E. coli was accomplished by the following procedure. The MJ1425 and MJ0490 genes were amplified by PCR, using genomic DNA from M. jannaschii (David E. Graham, Urbana, Ill.) as the template. The primers, 5′ CATGCATATGATTTTAAAACCAGAAAATGAA 3′ and 5′ GATCGGATCCTTATTCAATATAGTCCTCAAT 3′ derived from the MJ1425 DNA sequence and primers 5′ CATGCATATGAAAGTTACAATTATAGGAGC 3′ and 5′ GATCGGATCCTTATAAGTTTTTAACTTCTTC 3′ derived from MJ0490 DNA sequence were used. The PCR products, purified via absorption and desorption to a Qia quick spin column, were digested with NdeI and BamHI and were cloned into NdeI-BamHI-digested pT7-7 plasmid vector to obtain the constructs pT7-7-MJ1425 and pT7-7-MJ0490. The constructs were transformed to E. coli TB1 for plasmid preparation and to E. coli BL21(DE3) for protein expression. The expression plasmid for the malate dehydrogenase from Methanothermus fervidus (12) was a generous gift from R. Hensel (University of Essen, Essen, Germany); it was treated in the same manner as the M. jannaschii gene containing plasmids. The cells of E. coli BL21(DE3) containing the pT7-7-MJ1425 or pT7-7-MJ0490 plasmid were incubated in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 100 mg of ampicillin per liter at 37°C to an absorbance at 600 nm of 1.0.

Protein production was then induced by the addition of isopropylthio-β-d-galactoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.1 mM, and the cells were grown for an additional 4 h at 37°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 5 min) and were frozen at −20°C until used. High-level expression of the desired gene products was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (12% polyacrylamide) of the SDS-soluble cellular proteins.

Preparation and analysis of cell extracts.

Cell extracts were prepared by sonication of the cell pellets (∼300 mg [wet weight]) suspended in 3 ml of buffer [50 mM N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (TES) (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM mercaptoethanol] followed by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 10 min). SDS-PAGE analysis of the pellets and the cell extracts showed that most (>90%) of the overexpressed proteins were present in a soluble form. Heating the extracts at 80°C for 30 min followed by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 10 min) removed most of the E. coli proteins and left essentially pure solutions of the overexpressed proteins (95% pure). These solutions were used for the analyses reported here. The protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad Protein Assay.

Measurement of enzymatic activities.

The activities of the enzymes were measured spectrophotometrically at 366 nm at 70°C in 1-ml quartz cuvettes (12). The 366-nm wavelength was used so that higher concentrations of reduced pyridine nucleotides could be used. NADH and NADPH had molar absorptivities of 1,800 M−1 cm−1 and 1,900 M−1 cm−1, respectively, at 70°C at 366 nm. For the determination of the Km and Vmax values of the various substrates, the 1.0-ml assay mixture contained 0.1 M potassium phosphate (pH 8.0), 0.3 mM NADH or NADPH, and 0 to 8 mM concentrations of the indicated substrates. Oxalacetate at 1 and 2 mM was used for the determination of the Km and Vmax of NADH and NADPH, respectively. The reaction was started by the addition of 10 μl of a 1:10 dilution of the protein solution (2 to 5 mg/ml; Bio-Rad Protein Assay), and the time-dependent decrease in NADH/NADPH absorbance was monitored for 4 min. One unit of enzyme activity refers to 1 μmol of NADH or NADPH oxidized per min.

The oxidative activity was determined by following the reduction of NAD+ or NADP+ at 366 nm. The buffer used in this assay consisted of 0.4 M hydrazine and 1 M glycine, pH 9.5 (11). The concentrations of NAD+ and NADP+ were 2 mM; the reductant substrates were present at 0 to 8 mM. For the determination of Km and Vmax and their associated errors, the kinetic data were fitted with Lineweaver-Burke equation using KaleidaGraph for Macintosh (version 3.08d).

Product identification.

The products of the NADH/NADPH-dependent reductions of each of the substrates were identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The general procedure in each case was to incubate the enzyme with the substrates, isolate the products, convert the products into suitable methyl ester derivatives, and analyze them by GC-MS using a known sample as a reference. In the case of the identification of sulfolactate, 100 μl of a cell extract containing the protein encoded from gene MJ1425 was mixed with 275 μl of 50 mM TES (pH 8.0) and incubated for 1 h at 50°C in the presence of 13 mM NADH and 6.7 mM sulfopyruvate. After the addition of an equal volume of 95% ethanol, the sample was heated for 5 min at 100°C and centrifuged (10 min, 14,000 × g) to produce a clear solution. After evaporation of the ethanol, the residue was dissolved in 0.5 ml of water, passed through a Dowex 50-8X (H+) column (0.5 by 1.5 cm), and evaporated to dryness. After the sample was dissolved in methanol (100 μl), an ether solution of diazomethane (300 μl) was added which generated a cloudy yellow color, and the sample was clarified by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 5 min). The resulting separated clear solution was then evaporated to dryness, dissolved in methylene dichloride, and analyzed by GC-MS (29). The remaining compounds were assayed as their methyl esters, as previously described (13). The absolute stereochemistry of malate and α-hydroxyglutaric acid was established by GC-MS of their methyl ester derivatives using a type G-TA Chiraldex column (0.25 mm by 40 m; Advanced Separation Technologies Inc., Whippany, N.J.) programmed from 95 to 180°C at 3°C per min. GC-MS was used in these analyses so that positive identification of the GC peaks could be established even in the complex mixtures. Both of these samples gave very well separated peaks that were easily assigned to the respective R and S isomers.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Reactions catalyzed by the overproduced enzymes.

The MJ1425-encoded enzyme, which we call MdhI, catalyzed the NADH-dependent reduction of oxalacetate, α-ketoglutarate, sulfopyruvate, and to a much lower extent, 1-oxo-1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid (KHTCA) (Table 1). The Vmax/Km for reduction by NADPH was less than 2% of those observed with NADH. The MJ0490-encoded enzyme, which we call MdhII, catalyzed the reduction of only oxalacetate and sulfopyruvate. Either NADH or NADPH serves as reductant for these reactions, with NADPH being only marginally effective for the MdhI catalyzing reduction of oxalacetate and α-ketoglutarate. Based on the measured Vmax/Km for these different substrates and coenzymes, it is clear that the NADH-dependent reduction of sulfopyruvate by the MJ1425-derived enzyme is the most efficient reaction measured. The M. fervidus MdhIII (MF-MdhIII) catalyzed only the reduction of oxalacetate and sulfopyruvate. Like the MJ1425-encoded enzyme, this reduction proceeds more efficiently with NADH than with NADPH. Although the amino acid sequence of the M. fervidus enzyme is homologous to the MJ1425-encoded protein, this enzyme did not catalyze the reduction of α-ketoglutarate. Since the structure of the methanopterin C1 carrier in M. fervidus is not known, this finding may indicate that these cells simply do not produce α-hydroxyglutarate, since it is not needed for the biosynthesis of their C1 carrier. Because of the differences in the specificity of this enzyme compared with both the MJ1425- and MJ0490-encoded enzymes, we are calling this enzyme MdhIII.

TABLE 1.

NADH- and NADPH-dependent enzymatic reductions of various α-keto acids by the MJ1425-encoded enzyme, the MJ0490-encoded enzyme, and the MF-malate dehydrogenase

| Substrate | Cosubstratea | MJ1425 (MdhI)

|

MJ0490 (MdhII)

|

MF (MdhIII)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) | Vmax/Km (min−1 mg−1) | Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) | Vmax/Km (min−1 mg−1) | Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) | Vmax/Km (min−1 mg−1) | ||

| Oxalacetate | NADH | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 47 ± 2.0 | 356 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 29 ± 1.9 | 120 | 0.11 ± 0.027 | 27 ± 1.6 | 240 |

| Oxalacetate | NADPH | 5.32 ± 1.0 | 38 ± 3.6 | 7 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 49 ± 1.5 | 160 | 0.95 ± 0.20 | 34 ± 2.8 | 36 |

| Sulfopyruvate | NADH | 0.04 ± 0.008 | 370 ± 22 | 10,000 | 1.3 ± 0.032 | 43 ± 4.1 | 34 | 0.07 ± 0.019 | 120 ± 14 | 1,700 |

| Sulfopyruvate | NADPH | 0.21 ± 0.026 | 31 ± 1.7 | 148 | 0.19 ± 0.019 | 69 ± 5.0 | 590 | 0.21 ± 0.017 | 81 ± 2.3 | 390 |

| α-Ketoglutarate | NADH | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 49 ± 3.2 | 26 | NAb | NA | ||||

| KHTCA | NADH | 15 ± 6.7 | 6 ± 2.1 | 0.4 | NA | NA | ||||

The cosubstrate concentrations were 0.3 mM NADH and 0.3 mM NADPH.

NA, no activity detectable (<0.1 U/mg) at substrate concentrations up to 10 mM.

A consistent observation among the MdhI and MdhIII enzymes is the much lower Km for the substrates with NADH compared to those with NADPH. We have not found any examples of such large differences in the Km of substrate changes by the different pyridine nucleotides. The results can, however, be rationalized by the decreased affinity of the anionic substrates for the enzyme that has bound the more anionic NADPH. The Km and Vmax for NADH with the MJ1425-derived enzyme were, respectively, 0.01 ± 0.001 mM and 29 ± 0.5 U/mg at 1 mM oxalacetate. The Km and Vmax for the MJ0490-derived enzyme were, respectively, 0.01 ± 0.002 mM and 13 ± 0.26 U/mg at 2 mM oxalacetate.

The MJ1425-encoded enzyme catalyzed the oxidation of the S isomers of malate, α-hydroxyglutarate, and sulfolactate (Table 2). No reaction could be detected for the (R)-sulfolactate and the (R)-α-hydroxyglutaric acid, indicating that the MJ1425-encoded enzyme oxidizes only the S isomers. The MJ0490-encoded enzyme catalyzed the oxidation of (S)-malate and (S)-sulfolactate (observed only in the presence of NADP), whereas the MF-Mdh catalyzed these reactions only in the presence of NAD. Again, the MF-malate dehydrogenase—as we expected from its relationship to the MJ1425-encoded enzyme—did not accept (S)-α-hydroxyglutarate as a substrate. (S)- and (R)-lactate were not oxidized by any of the enzymes with NAD or NADP.

TABLE 2.

NAD+- and NADP+-dependent enzymatic oxidations of various α-hydroxy acids by the MJ1425-encoded enzyme, the MJ0490-encoded enzyme, and the MF-malate dehydrogenase

| Substrate | Cosubstratea | MJ1425 (MdhI)

|

MJ0490 (MdhII)

|

MF (MdhIII)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) | Vmax/Km (min−1 mg−1) | Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) | Vmax/Km (min−1 mg−1) | Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) | Vmax/Km (min−1 mg−1) | ||

| (S)-Malate | NAD+ | 0.02 ± 0.004 | 11 ± 0.56 | 480 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.6 ± 0.01 | 4 | 0.05 ± 0.12 | 1.9 ± 0.064 | 37 |

| (R)-Malate | NAD+ | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 3 ± 0.2 | 9 | NDb | ND | ND | ND | ||

| (S)-Malate | NADP+ | 0.03 ± 0.004 | 2 ± 0.04 | 57 | 0.025 ± 0.005 | 3 | 110 | ND | ND | |

| (S)-Sulfolactate | NAD+ | 0.04 ± 0.006 | 22 ± 1.7 | 551 | NAc | 0.07 ± 0.015 | 1.6 ± 0.08 | 22 | ||

| (S)-Sulfolactate | NADP+ | 0.39 ± 0.006 | 2 ± 0.26 | 6 | 4.6 ± 0.06 | 3 ± 0.22 | 1 | ND | ND | |

| (S)-α-Hydroxyglutarate | NAD+ | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 8 ± 0.4 | 15 | NA | ND | ND | |||

The cosubstrate concentrations were 1 mM NAD or 1 mM NADP.

ND, not determined.

NA, no activity detectable (<0.1 U/mg) at substrate concentrations of up to 10 mM.

The Km and Vmax values for the MJ1425-encoded enzyme (Table 1) indicate that the enzyme at expected physiological concentrations of substrates would produce both (S)-hydroxyglutaric acid and (S)-malate. If the MJ1425-encoded enzyme were present at a concentration high enough to supply all of the malate needed by the cells, it would also produce far more (S)-hydroxyglutaric acid than would be needed for the biosynthesis of methanopterin, despite the fact the enzyme has a higher Km for α-ketoglutarate than for oxalacetate. Thus, MdhI can clearly produce the (S)-α-hydroxyglutaric acid required for the biosynthesis of methanopterin by the reduction of α-ketoglutarate.

Sulfopyruvate was found to be reduced to sulfolactate by all of the enzymes much more efficiently than oxalacetate (Table 1). Furthermore, the reaction kinetics of the MJ1425-encoded enzyme and the MF-malate dehydrogenase showed substrate inhibition at very low sulfopyruvate concentrations (0.1 mM for both enzymes), as has been reported with other malate dehydrogenases (14). This phenomenon has also been observed with the malate dehydrogenase from ox heart mitochondria but with oxalacetate used as the substrate (5). The malate dehydrogenase from pig heart mitochondria has been shown to use sulfopyruvate very poorly as substrate (26); the Vmax/Km value was 460 times less than that for oxalacetate. Sulfolactate was not a substrate for the chicken liver NADP-dependent malate enzyme but was in fact an inhibitor (27). The MJ0490-encoded enzyme also prefers sulfopyruvate as a substrate, but the differences of the Vmax/Km values compared to those for oxalacetate are not as pronounced as with the MJ1425-encoded enzyme or the MF-malate dehydrogenase. In the biosynthesis-relevant direction—that is, the oxidation of (S)-sulfolactate to sulfopyruvate (30)—only the MJ1425-encoded enzyme and the MF-malate dehydrogenase were found to oxidize (S)-sulfolactate using NAD as the oxidant, whereas the MJ0490-encoded enzyme prefered to oxidize (S)-malate over (S)-sulfolactate using NADP (Table 2). None of the enzymes catalyzed the oxidation of (R)-sulfolactate. These results indicate the possible involvement of the MJ1425-encoded enzyme and the MF MdhIII in the coenzyme M biosynthetic pathway and are consistent with only the (S)-sulfolactate being an intermediate in coenzyme M biosynthesis, as previously described (30).

The MJ1425-encoded enzyme could carry out the reduction of the KHTCA with NADH. Despite the fact that the high Km of 15 mM makes the reduction of questionable biochemical relevance, the GC-MS analysis of the produced isomer was shown to be xylo-HHTCA, an isomer different from that involved in HTCA biosynthesis (31). Considering the stereospecificity of the MJ1425-encoded enzyme for the (S)-isomers (Table 2), the isomer produced by the MJ1425-encoded enzyme could be assigned to (S)-xylo-HHTCA. From these results, we conclude that the naturally occurring isomers of HHTCA must be produced by an enzyme that reduces the keto acid group to the hydroxy acid with R stereochemistry, as opposed to the S stereochemistry observed here. These results clearly demonstrate that neither of these enzymes is involved in the biosynthesis of the HHTCA intermediates used in HTCA biosynthesis.

Pyruvate was found not to serve as a substrate for either enzyme with either of the reduced pyridine nucleotides. Thus, the source of the (S)-lactate present in coenzyme F420 is still unknown. This finding could indicate that the lactate moiety of F420 may arise by an alternate route, perhaps by the reduction of PEP.

If the MJ1425-encoded enzyme is indeed involved in the biosynthesis of these coenzymes, we may expect that this gene could be in a cluster of other genes that are involved in the biosynthesis of the coenzymes. In M. jannaschii, the MJ1425 gene is located within a group of genes that has no clear relationship to coenzyme biosynthesis. However, the homologous gene in M. thermoautotrophicum, MHT1205, is next to the recently established sulfopyruvate decarboxylase genes MTH1206 and MTH1207 encoding another enzyme involved in coenzyme M biosynthesis. This finding thus establishes a genetic link of this gene to the biosynthesis of coenzyme M.

In conclusion, the data presented here are consistent with the idea that the MdhI enzyme may participate in the biosynthesis of coenzyme M and methanopterin by catalyzing the oxidation of sulfolactate to sulfopyruvate in the biosynthetic pathway to coenzyme M and in supplying α-hydroxyglutarate for the biosynthesis of methanopterin. This enzyme would thus function in these cells in a multiple capacity, not only functioning as part of a NADPH:NAD transhydrogenase (22) but also supplying metabolites for the biosynthesis of coenzymes. This enzyme thus joins an established but growing list of enzymes, such as hexokinase (4), transaminases (20), fatty acid synthases, acetohydroxy acid synthases (23a), nucleoside mono and diphosphate kinases (19), and the AksA enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of coenzyme B (13), that are able to catalyze more than one metabolically essential reaction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation grant MCB963086.

REFERENCES

- 1.Birktoft J J, Fernley R T, Bradshaw R A, Banaszak L J. Amino acid sequence homology among the 2-hydroxy acid dehydrogenases: mitochondrial and cytoplasmic malate dehydrogenases from a homologous system with lactate dehydrogenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;79:6166–6170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.20.6166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J-F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Weidman J F, Fuhrmann J L, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Kelley J M, Peterson J D, Sadow P W, Hanna M C, Cotton M D, Roberts K M, Hurst M A, Kaine B P, Borodovsky M, Klenk H-P, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bur D, Lutaen M A, Wynn H, Provencher L R, Jones J B, Gold M, Friesen J D, Clark A R, Holbrook J J. An evaluation of the substrate specificity and asymmetric synthesis potential of the cloned L-lactate dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Can J Chem. 1989;67:1065–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crane R K. Hexokinases and pentokinases. In: Boyer P D, Lardy H, Myrback K, editors. The enzymes. Vol. 6. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1962. pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies D, Kun E. Isolation and properties of malic dehydrogenase from ox-heart mitochondria. Biochem J. 1957;1957:307–316. doi: 10.1042/bj0660307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eirich L D, Vogels G D, Wolfe R S. Proposed structure of coenzyme F420 from Methanobacterium. Biochemistry. 1978;17:4583–4593. doi: 10.1021/bi00615a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorris L G M, van der Drift C, Vogels G D. Separation and quantification of cofactors from methanogenic bacteria by high-performance liquid chromatography: optimum and routine analyses. J Microbiol Methods. 1988;8:175–190. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorris L G M, van der Drift C. Cofactor contents of methanogenic bacteria reviewed. Biofactors. 1994;4:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goward C R, Nicholls D J. Malate dehydrogenase: a model for structure, evolution, and catalysis. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1883–1888. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill R K, Chan T H. The absolute configuration of pantothenic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;38:181–183. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohorst J J. L-(−)-Malate determination with malate dehydrogenase and DPN. In: Bergmeyer H-U, editor. Methods of enzymatic analysis. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1963. pp. 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honka E, Fabry S, Niermann T, Palm P, Hensel R. Properties and primary structure of the L-malate dehydrogenases from the extremely thermophilic archaebacterium Methanothermus fervidus. Eur J Biochem. 1990;188:623–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell D M, Harich K, Xu H, White R H. The α-keto acid chain elongation reactions involved in the biosynthesis of coenzyme B (7-mercaptoheptanoylthreonine phosphate) in methanogenic Archaea. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10108–10117. doi: 10.1021/bi980662p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kagawa T, Bruno P L. NADP-malate dehydrogenase from leaves of Zea mays: purification and physical, chemical and kinetic properties. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;260:674–695. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim M-J, Whitesides G M. l-Lactate dehydrogenase: substrate specificity and use as a catalyst in the synthesis of homochiral 2-hydroxy acids. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:2959–2964. doi: 10.1007/BF02921743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langelandsvik A S, Steen I H, Birkeland N K, Lien T. Properties and primary structure of a thermostable L-malate dehydrogenase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:59–67. doi: 10.1007/s002030050470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leigh J A, Reinhart L L, Jr, Wolfe R S. Structure of methanofuran, the carbon dioxide reduction factor of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:3636–3640. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin X, White R H. Occurrence of coenzyme F420 and its γ-monoglutamyl derivative in nonmethanogenic archaebacteria. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:444–448. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.1.444-448.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parks R E, Jr, Agarwal R P. Nucleoside diphosphokinases. In: Boyer P D, editor. The enzymes, 3d ed. VIII. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pittard A J. Biosynthesis of the aromatic amino acids. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 458–484. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Potheir B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Safer H, Patwell D, Prabhakar S, McDougall S, Shimer G, Goyal A, Pietrokovski S, Church G M, Daniels C J, Mao J, Rice P, Nölling J, Reeve J N. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautrophicum. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson H, Tersteegen A, Thauer R K, Hedderich R. Two malate dehydrogenases in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Arch Microbiol. 1998;170:38–42. doi: 10.1007/s002030050612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thurston-Solow B, White R H. The absolute stereochemistry of 2-hydroxyglutaric acid present in methanopterin. Chirality. 1997;9:678–680. [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Umbarger H E. Biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 442–457. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Beelen P, Strassen A P M, Bosch J W G, Vogels G D, Guijt W, Haasnoot C A G. Elucidation of the structure of methanopterin, a coenzyme from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, using two-dimensional nuclear-magnetic-resonance techniques. Eur J Biochem. 1984;138:563–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb07951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Beelen P, Labro J F A, Labro J T, Keltjens J T, Geerts W J, Vogels G D, Laarhoven W H, Haasnoot C A G. Derivatives of methanopterin, a coenzyme involved in methanogenesis. Eur J Biochem. 1984;139:359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinstein C L, Griffith O W. β-Sulfopyruvate: chemical and enzymatic syntheses and enzymatic assay. Anal Biochem. 1986;156:154–160. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein C L, Griffith O W. Cysteinesulfonate and β-sulfopyruvate metabolism: partitioning between decarboxylation, transamination, and reduction pathways. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3735–3743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White R H. Biosynthesis of coenzyme M (2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid) Biochemistry. 1985;24:6487–6493. [Google Scholar]

- 29.White R H. Intermediates in the biosynthesis of coenzyme M (2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid) Biochemistry. 1986;25:5304–5308. [Google Scholar]

- 30.White R H. Characterization of the enzymatic conversion of sulfopyruvate and L-cysteine into coenzyme M (mercaptoethanesulfonic acid) Biochemistry. 1988;27:7458–7462. [Google Scholar]

- 31.White R H. Structural diversity in the methanofuran from different methanogenic bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4544–4597. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4594-4597.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White R H. Biosynthesis of methanopterin. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5397–5404. doi: 10.1021/bi00474a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White R H. Structure of the modified folates in the thermophilic archaebacteria Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochemistry. 1993;32:745–753. doi: 10.1021/bi00054a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White R H. Structures of the modified folates in the extremely thermophilic archaebacteria Thermococcus litoralis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3661–3663. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3661-3663.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White R H. Biosynthesis of methanopterin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3447–3456. doi: 10.1021/bi952308m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White R H. Structural characterization of modified folates in Archaea. Methods Enzymol. 1997;281:391–401. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)81046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilks H M, Halsall D J, Atkinson T, Chia W N, Clarke A R, Holbook J J. Designs for a broad substrate specificity keto acid dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8587–8591. doi: 10.1021/bi00489a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]