Abstract

Biodiesel can be altered when exposed to air, light, temperature, and humidity. Other factors, such as microbial or inorganic agents, also interfere with the quality of the product. In the present work, the Rancimat method and mid-infrared spectroscopy associated with chemometry, were used to identify the oxidation process of biodiesel from different feedstocks and to evaluate the antioxidant activity of butylated hydroxytoluene. The study was carried out in four steps: preparation of biodiesel samples with and without the antioxidant agent, degradation of the samples under the effect of light and heating at 70 °C, measurements of the induction period, obtention of infrared spectra, and multivariate analysis. The Fourier transform mid-infrared spectroscopy was used in combination with multivariate analysis, using techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA). The Rancimat results showed that babassu biodiesel has a higher resistance to oxidative degradation, while chicken biodiesel is the most susceptible to degradation; on the other hand, the antioxidant activity was more effective with chicken biodiesel, demonstrating that the antioxidant effect depends on the feedstock used in the production of biodiesel. The oxidative stability of babassu oil-, corn oil-, and chicken fat-based biodiesels decreased during storage both in the presence of light and at high temperature. Prior to PCA, all spectra were pre-processed with a combination of Savitzky–Golay smoothing filter with a 7-point window, baseline correction, and mean-centered data. The use of mid-infrared spectroscopy associated with PCA revealed the first two components to explain the greater variability of data, representing over 75% of total variation for all analyzed systems. In addition, it was able to separate the biodiesel samples according to the fatty acid profile of its feedstock, as well as the type of degradation to which it was subjected, the same being confirmed by HCA.

Introduction

Biodiesel is a fuel produced from triglycerides derived from renewable sources, such as vegetable oils and animal fats. These sources are subjected to a chemical reaction called transesterification in which they react with an alcohol in the presence of a catalyst to produce an alkyl ester (biodiesel) and glycerol.1 Several studies have been carried out on the production of biodiesel from low-cost raw materials, including waste frying oil2,3 and animal fat,4,5 since these inputs are of great interest for both ecological and economic reasons. Edible vegetable oils are one of the main raw materials for the production of biodiesel. However, due to objections to the use of edible oils for fuel production, other sources, such as non-edible oils of vegetable origin, waste fats with a high content of free fatty acids (FFA), etc., have been receiving more attention.6−8 The fact that biodiesel can be obtained from different raw materials makes it possible to obtain fuels with different physicochemical properties and chemical compositions.9 Although biodiesel is a promising alternative to replace petroleum diesel, it has some disadvantages, such as quality drop as a result of atmospheric oxidation during storage, when it becomes more susceptible to degradation. This causes changes in its properties over time due to hydrolytic, microbiological, and oxidative reactions. These degradation processes can be accelerated by exposure to air, moisture, metals, light, and heat or even environments contaminated by microorganisms.10 This phenomenon eventually results in insoluble deposits and increases the values of various oil properties, such as acidity index, peroxide index and iodine value, kinematic viscosity, density, and polymer content.11

In Brazil, to certify the quality of biodiesel it is necessary to analyze 24 parameters, including oxidative stability.12 This parameter reflects the susceptibility of biodiesel to undergo oxidative degradation, which is a key issue for its wide commercialization.13 Outside the specifications, the oxidative stability can cause problems during fuel storage and also affect vehicle performance, as a result of deposit formation on engine parts that can cause clogging in the fuel filter.14,15 Most of the biodiesels produced requires the addition of antioxidants to comply with the oxidative stability requirements listed in both ASTM D6751 and EN 14214.16,17 The antioxidants help to slow down the oxidation process in biodiesel caused by free radicals.18 These antioxidants can be either natural or synthetic antioxidants. Natural antioxidants occur naturally in vegetable oils, such as tocopherols, while synthetic antioxidants are derived from petroleum and have been utilized to improve the oxidation and storage stability of biodiesel, such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), tert-butylhydrooquinone (TBHQ), and propyl gallate (PrG).19

The standard method for determining the oxidative stability of biodiesel is the Rancimat, which assesses the time required to reach a critical oxidation point (induction period) and which, according to ANP specifications, must present a minimum of 8 h at 110 °C.12 It is a simple but time-consuming analytical method.

Several works with different focuses and strategies have been applied in the classificatory analysis of biodiesel. Mueller et al.20 showed that the use of infrared spectroscopy associated with multivariate analysis of the data was able to identify the vegetable oils used as raw materials in the production of biodiesel, while dos Santos et al.21 used a multivariate approach to classify diesel/biodiesel mixtures ranging between 0 and 100% of biodiesel content through discriminant analysis and cluster analysis applied to Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), discriminating between the oil source and the percentage of ester in the mixture. Spectroscopic techniques such as Fourier transformed mid-infrared (FT-MIR), near infrared (NIR), and Raman were used to discriminate 10 different samples of oils and fats and compare the performance of these different methods. The spectral features of edible oils and fats were studied, and the characteristic vibrations of the C=C double bond were identified and used for discriminant analysis (DA).22 A correlation between the near-infrared spectrum of a biodiesel sample and its feedstock was performed by Balabin and Safieva.23 This correlation was used to classify the fuel samples into 10 groups according to their origin (vegetable oil): sunflower, coconut, palm, soybean/soybean, cottonseed, castor bean, jatropha, etc. Four different multivariate data analysis techniques are used to solve the classification problem, including regularized discriminant analysis (RDA), partial least squares method/projection onto latent structures (PLS-DA), K-nearest neighbors (KNN) technique, and support vector machines (SVM). Classifying biodiesel by feedstock type (base stock) was successfully achieved, and the KNN and SVM methods were considered highly effective for biodiesel classification by feedstock oil type.

Although the methodologies used in the present study are well established and there are several works in the literature on the theme of biodiesel and oxidative stability,24,25 to our knowledge, there is no research that simultaneously evaluate the oxidative stability of babassu oil-, corn oil-, and chicken fat-based biodiesels by Rancimat, infrared, and chemometry. In addition, most works focus on the discrimination of biodiesel by feedstock type. In the present study, PCA and HCA were able to classify the biodiesel samples by feedstock type, as well as by the chemical changes caused by the different types of degradation (light and heating).

Results and Discussion

Oxidative Stability for the Oils and Fats Used in This Study

According to Lin et al.26 the oxidative stability of biodiesel is intrinsically related to the characteristics of the raw material, which makes it more susceptible to degrading agents. Based on this information, an analysis of the induction period of the raw material used for the production of biodiesels was carried out. Figure 1 shows the values of the induction periods for the oil and fat samples.

Figure 1.

Induction period vs raw materials used in biodiesel production. CHF, chicken fat; CO, corn oil; BO, babassu oil.

Animal fats, when compared to vegetable oils, have a higher percentage of palmitic and oleic fatty acids and a lower content of linoleic and linolenic fatty acids.27 The chicken fat presented low oxidative stability, probably due to the composition of the fat ingredients that normally contain large amounts of free fatty acids.28 On the other hand, the low oxidative stability of some vegetable oils is a result of the unsaturated fatty acids present in their composition, such as oleic, linoleic, and linolenic acids.29 The higher the degree of unsaturation, the more susceptible they will be to oxidation, thus justifying the low induction period presented by corn oil. The corn oil is made up of approximately 83% unsaturated fatty acids,30 as opposed to babassu oil, which consists of 85% saturated fatty acids.31 Although vegetable oils present a higher degree of unsaturation, they tend to oxidize more slowly than animal fat due to the presence of tocopherols, which act as natural antioxidants.

The induction period found for babassu biodiesel is shown in Figure 2. It can be observed that the presence of lauric fatty acid (C 12:0) provides high oxidative stability to the babassu biodiesel, which can be observed in the average induction period of 10.72 h for the pure biodiesel sample. It is also noticeable that storage factors such as light and heat cause a reduction in the induction period and that the presence of the antioxidant (BHT) reduces the degradation process by increasing the induction period.

Figure 2.

Values of the induction period for babassu biodiesel with and without the addition of the antioxidant BHT under different degrading conditions. BB, babassu biodiesel; BBBHT, babassu biodiesel with BHT; BBL, babassu biodiesel in the presence of light; BBLBHT, babassu biodiesel with BHT in the presence of light; BBH, heated babassu biodiesel; BBHBHT, heated babassu biodiesel containing BHT.

The corn biodiesel, when compared to babassu biodiesel, presents lower oxidative stability, with an induction period of 4.37 h, and linoleic acid as the predominant fatty acid (C 18:2), an unsaturated acid more susceptible to the oxidative process. The storage conditions caused a greater degradation of the samples, as it was observed for the babassu biodiesel samples. The results found for the induction period are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Induction periods for corn biodiesel with and without the addition of the antioxidant BHT under different degradation conditions. CB, corn biodiesel; CBBHT, corn biodiesel with BHT; CBL, corn biodiesel in the presence of light; CBLBHT, corn biodiesel with BHT in the presence of light; CBH, heated corn biodiesel; CBHBHT, heated corn biodiesel containing BHT.

According to Lee and Foglia,32 chicken fat contains about 60% of unsaturated fatty acids, being, therefore, more susceptible to oxidative degradation. In addition, animal fats do not contain tocopherols, which are natural antioxidants present in vegetable oils. This, and the fact that the raw material used presented low oxidative stability, contributed to the low induction period observed for chicken biodiesel, 0.44 h, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Induction period values for chicken biodiesel with and without the addition of the antioxidant BHT under different degrading conditions. CHB, chicken biodiesel; CHBBHT, chicken biodiesel with BHT; CHBL, chicken biodiesel in the presence of light; CHBLBHT, chicken biodiesel with BHT in the presence of light; CHBH, heated chicken biodiesel; CHBHBHT, heated chicken biodiesel containing BHT.

The degradation of the samples became even more evident when subjected to storage conditions, which can be seen by the very low values of the induction period, 0.08 and 0.0, for the samples without BHT when subjected to the influence of light and heating, respectively. The addition of the antioxidant significantly increased the induction period of the biodiesel samples. The antioxidant (BHT) showed greater effectiveness when used in chicken biodiesel. These results confirm the studies by Varatharajan and Pushparani, which shows that BHT is more effective in preserving animal fat than in vegetable oil.33

Biodiesel Analysis by Infrared Spectroscopy

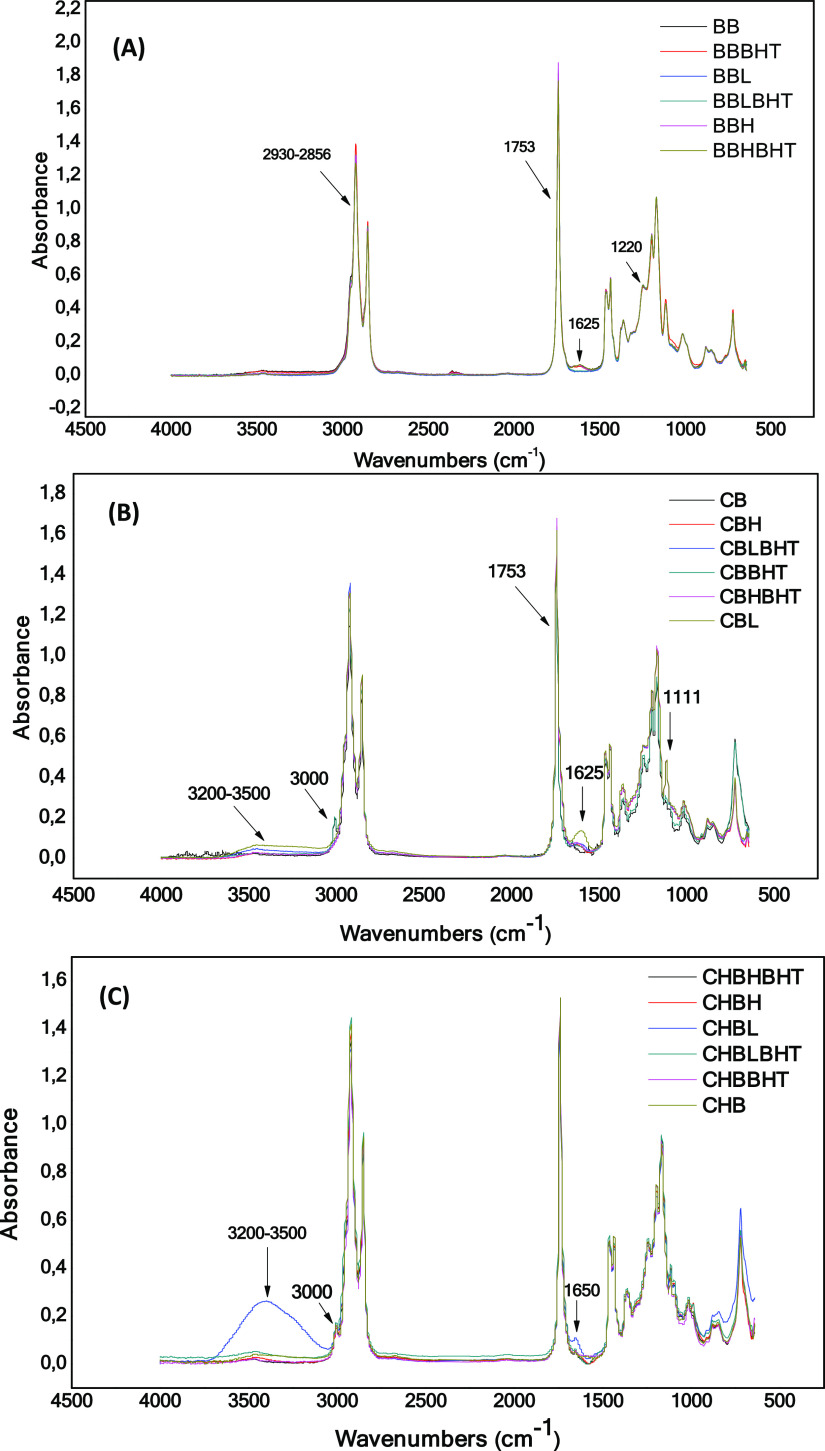

The qualitative analysis of babassu biodiesel in the infrared region revealed characteristic absorption bands for the main functional groups present in the molecules of this fuel. Figure 5A shows absorption bands characteristic of intense axial deformation of the group C=O (carbonyl) and an average axial absorption of C–O (ester) at 1753 and 1220 cm–1, respectively. It is also possible to observe bands attributed to the axial deformation of the C–H (sp3) bond at 2930–2856 cm–1, confirmed by the band around 1380 cm–1 derived from the symmetric angular deformation of the C–H bond of the methyl group and another at 720 cm–1 attributed to the out-of-plane asymmetric angular deformation of σ (sp3-s) C–H.34,35 It was not possible to verify signals corresponding to the antioxidant in the biodiesel spectrum. However, a small band appears at approximately 1625 cm–1 when biodiesel is subjected to external factors such as the presence of light. According to van de Voort et al.,36 this region is characteristic of the angular deformation of HOH. Figure 5B shows the infrared spectra for corn biodiesel with and without the addition of BHT under the influence of different storage conditions. The image shows a strong band at 1753 cm–1 referring to the carbonyl group, medium bands referring to axial deformation of CO (ester) at 1170 and 1207 cm–1, and the out-of-plane angular deformation of (CH2)n groups at 720 cm–1. It is also possible to observe a band around 3000 cm–1 referring to the group H—C= (presence of unsaturation), which is not observed for the babassu biodiesel since the absence of this absorbance is related to its low content of unsaturation. Regarding the BHT influence, again, it was not possible to observe signs of the antioxidant in the corn oil biodiesel spectrum. Spectral changes in 1111 and 1625 cm–1 and between 3200 and 3500 cm–1 appear as a characteristic of C–O (ester) axial deformation, HOH angular deformation, and OH stretch vibration, respectively. The latter is related to the formation of peroxides and acids generated as oxidation products. In addition, the band around 3000 cm–1 for cis C=C bonds disappears with the oxidation time, indicating the replacement of a hydrogen of the cis double bond by a free radical.30

Figure 5.

Infrared spectra of biodiesels: control sample and degraded samples with and without the addition of the antioxidant BHT. (A) Babassu biodiesel, (B) corn biodiesel, and (C) chicken fat biodiesel.

The chicken fat biodiesel, as well as corn oil biodiesel, undergoes spectral changes, which indicate the degradation of biodiesel caused by storage conditions. The changes appear at 1650 cm–1, as C=C stretching vibrations of olefins, and between 3200 and 3500 cm–1, with the latter appearing more sharply, as can be seen in Figure 5C. In both cases, the incidence of light on the biodiesel was the one that most influenced the degradation; however, in the corn biodiesel, there was the elimination of the band close to 3000 cm–1, corresponding to the stretching of the C=C bond, which was not observed for chicken biodiesel. This behavior is an indication that CHB, as it has a higher proportion of saturated fatty acids in its composition when compared to CB, should be less susceptible to the replacement of a hydrogen from a double bond by a free radical. It is also observed that the experiments carried out in the presence of BHT tend to inhibit the oxidation process of biodiesel since the profile of the spectra is close to the control biodiesel.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Corn, Babassu, and Chicken Biodiesel Samples

Figure 6A shows the score plot for PC1 (94% variance) versus PC2 (4% variance) for corn biodiesel. When subjected to the presence of light and heating, there is a clear separation between freshly prepared and degraded biodiesel, when analyzed from the perspective of the first component. This behavior confirms what was observed in the analysis of the spectra. According to PC2, light exposure caused a greater spectral variation, but the addition of BHT was effective in reducing the oxidation process. A similarity between the data distribution in the PCA and the values presented by the Rancimat method was also noted, meaning that the samples subjected to heating and light where the antioxidant was added are aligned with the natural corn biodiesel sample. The trends observed in the principal component analysis were confirmed by the dendrogram obtained by HCA (Figure 6B). Two groups are observed, a smaller one formed by the control biodiesel with and without BHT and a larger one formed by the degraded biodiesel.

Figure 6.

(A) PC1 versus PC2 score plot of corn biodiesel infrared spectra. (B) HCA dendrograms of corn biodiesel infrared spectra. CB, corn biodiesel; CBBHT, corn biodiesel with BHT; CBL, corn biodiesel in the presence of light; CBLBHT, corn biodiesel with BHT in the presence of light; CBH, heated corn biodiesel; CBHBHT, heated corn biodiesel with BHT.

Analyzing the score plot for babassu biodiesel (Figure 7A), it is possible to observe that, unlike what happened with the CB, the data show a certain dispersion of the scores, that is, group discrimination is not as evident as in the previous case. This is probably because this raw material consists mostly of saturated fatty acids. Approximately 50% of babassu oil is made up of lauric acid (C12:0). Thus, babassu biodiesel is more resistant to the oxidation process. Figure 7A also shows a separation between the biodiesel submitted to the degradation process and the control biodiesel, with the PC1 × PC2 plot representing 78% of the total variance. The exploratory analysis by PCA of the spectra of degraded biodiesel by light and heating did not show significant differences for the samples with BHT, indicating that the antioxidant has little influence on the structural changes of the degraded babassu biodiesel. Biodiesels subjected to heating, with and without the addition of BHT, positioned themselves with negative scores on PC1 and positive on PC2, while those exposed to light showed negative scores on both PC1 and PC2.

Figure 7.

(A) PC1 versus PC2 scores plot of babassu biodiesel infrared spectra. (B) HCA dendrograms of babassu biodiesel infrared spectra. BB, babassu biodiesel; BBBHT, babassu biodiesel with BHT; BBL, babassu biodiesel in the presence of light; BBLBHT, babassu biodiesel with BHT in the presence of light; BBH, heated babassu biodiesel; BBHBHT, heated babassu biodiesel with BHT.

The data used for the construction of the score plot were also applied to obtain the dendrogram (Figure 7B). A similarity was observed between the two graphs, which means that they present the same tendency for separation between groups. Considering the degradation of biodiesel, it was observed that inside the cluster, there was a subdivision into two others sub-clusters. These subdivisions were associated with the type of degradation (by light or heating).

Both chicken fat and corn oil biodiesels have the structure of their alkyl esters altered when subjected to the degradation process since chicken fat biodiesel consists mostly of unsaturated fatty acids (40% oleic acid).37 In addition, animal fat is low in tocopherol, which makes it more susceptible to oxidation reactions. Figure 8A shows the score plot for the discrimination of chicken fat biodiesel when subjected to degradation processes. The best visual representation was obtained from the PC1 × PC2 plot, representing 93% of the total variation. Light presented a greater effect on biodiesel degradation, illustrating a typical case of photooxidation. In liquids like biodiesel, light penetrates in depth, which results in larger portions of FAME (fat acid methyl ester) become deteriorated.29 Studies on the influence of light and temperature on biodiesel stability were presented by Aquino et al.38 where tests with copper and brass immersed in biodiesel exposed to light caused higher corrosion rates than when subjected to high temperatures. The trends observed in the principal component analysis were confirmed by the HCA dendrogram (Figure 8B), where two clusters are observed, one for the biodiesel degraded by light and the other for the heated samples with and without BHT.

Figure 8.

(A) PC1 versus PC2 scores plot of chicken fat biodiesel infrared spectra. (B) HCA dendrograms of chicken fat biodiesel infrared spectra. CHB, chicken biodiesel; CHBHT, chicken biodiesel with BHT; CHBL, chicken biodiesel in the presence of light; CHBLBHT, chicken biodiesel with BHT in the presence of light; CHBH, heated chicken biodiesel; CHBHBHT, heated chicken biodiesel with BHT.

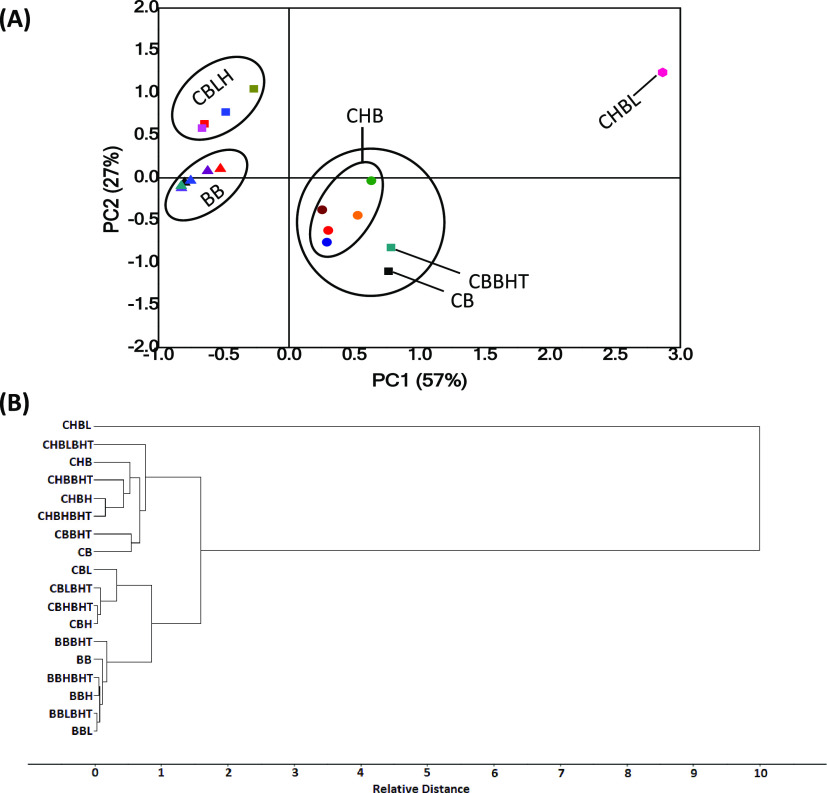

When the spectra of the three biodiesel samples (corn, babassu, and chicken) under the different degrading conditions were subjected together to the PCA analysis, four very distinct groups can be observed (Figure 9A), being the first component responsible for 57% of the data variation. The separation in PC1 is mainly due to the chemical decomposition of the samples since the corn biodiesel, when oxidated, gradually shows a decrease in the band corresponding to the cis bond (C=C), becoming structurally more similar to the more saturated babassu biodiesel. The control corn biodiesel with BHT is very similar to the chicken biodiesel when subjected to heating and the incidence of light because chicken biodiesel does not suffer interference in the cis bond (C=C). However, exposure to light during the storage of chicken biodiesel causes significant changes in its composition. It can also be observed that the protective effect of BHT was greater for chicken biodiesel exposed to light. A similar behavior was observed in the HCA plot (Figure 9B), where chicken biodiesel in the presence of light presented itself as a sample very different from the others. The other samples were grouped into three other classes: chicken biodiesel (natural and degraded by heating) and natural chicken biodiesel, corn biodiesel (natural and degraded), and babassu biodiesel (natural and degraded).

Figure 9.

(A) PC1 versus PC2 score plot of the infrared spectra of corn, babassu, and chicken biodiesels. (B) HCA dendrograms of the infrared spectra of corn, babassu, and chicken biodiesel. BB, natural and degraded babassu biodiesel; CBLH, corn biodiesel in the presence of light and heating; CHB - natural and degraded chicken biodiesel without presence of light; CB, corn biodiesel; CBBHT, corn biodiesel with BHT; CHBL, chicken biodiesel in the presence of light.

Figure 10A shows the scores plot for joint analysis of biodiesel samples and the raw material used in their production. PC1 (with 74% of the variance) separates biodiesel from oil samples, while PC2 (23%) separates the samples of biodiesel and babassu oil from the samples of biodiesel and corn and chicken fat oils. Although the samples of vegetable oils and different types of biodiesel are on opposite sides in Figure 10, it is evident that the origin of the oil has an influence on their location in the plot, noticed by the similar distribution of both biodiesel and oils samples over PC2. The dendrogram (Figure 10B) grouped the samples into three groups with characteristics similar to those presented by the PCA, obeying the same similarity relationship.

Figure 10.

(A) PC1 versus PC2 score plot of the infrared spectra of biodiesel and the raw material used in its production. (B) HCA dendrograms of the biodiesel and raw material infrared spectra. CB, corn biodiesel; CO, corn oil; CHF, chicken fat oil; CHB, chicken biodiesel; BB, babassu biodiesel; BO, babassu oil.

Conclusions

In the present work, Rancimat and infrared combined with PCA and HCA were used to evaluate the oxidative stability of three biodiesels obtained from different raw materials and subjected to storage conditions such as high temperature and the presence of light. The antioxidant effectiveness of the BHT was also evaluated.

The analyses carried out with Rancimat showed in general that the exposure of biodiesel to light was the storage condition that most affected oxidative stability. Among the studied biodiesels, babassu showed a higher resistance to oxidative degradation and BHT has higher antioxidant effectiveness for chicken biodiesel. The results indicate that it is possible to understand and identify changes in the biodiesel degradation process quickly and without the need for sample preparation, as well as the raw material used in the production of biodiesel, using the ATR/FTIR method combined with multivariate chemometric techniques (PCA and HCA). The scores associated with the principal components revealed that the spectral characteristics extracted are correlated with the chemical structure of the analyzed biodiesels. Both techniques, Rancimat and infrared combined with chemometry, provide information on the different oxidative levels. However, the formation of volatile species, which occurs only in the last oxidation stage, has been verified only in the Rancimat method.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Samples

All reagents were of analytical grade and were used as received without further purification. Ethanol and methanol were acquired by Merck. Sodium hydroxide and potassium hydroxide were purchased from Synth. The antioxidant BHT was purchased from Isofar. Chicken fat and commercial oils from corn and babassu were used as raw materials for the production of biodiesel. The samples were stored in plastic bottles and kept refrigerated until the beginning of biodiesel production.

Biodiesel Production

Biodiesel samples at laboratory scale were prepared by transesterification of vegetable oils and animal fat using the following procedure: (a) for the biodiesel production from chicken oil, the procedure was performed as described by Lin and

Tsai39 with modifications using 1% catalyst (NaOH) and a methanol/oil molar ratio of 12:1, with a reaction time of 2 h at 40 °C under magnetic stirring. The reaction mixture was kept under stirring and controlled temperature. The separation step by the difference in density between the light (biodiesel) and heavy (glycerin) phases was processed in a separating funnel. (b) For the production of biodiesel from corn and babassu, the oils were dried in an oven for 2 h at 80 °C. A total of 1.5 g of the potassium hydroxide catalyst (KOH) and 35 mL of methanol were used for every 100 g of vegetable oil. The reaction products were obtained after 2 h of stirring at 40 °C and separated in a separating funnel.

Identification and Storage of Biodiesel Samples under Different Degrading Conditions

The data set consisted of pure babassu biodiesel (BB), corn biodiesel (CB), and chicken biodiesel (CHB) samples. To evaluate the antioxidant effect, additional samples of babassu, corn, and chicken biodiesel containing BHT (1000 mg/kg), identified as BBBHT, CBBHT, and CHBBHT, respectively, were analyzed. The biodiesel samples were subjected to oxidation for 5 days in two different conditions, natural light exposure, and heating in an oven at 70 °C. A total of 21 samples were analyzed.

IR Spectroscopic Analysis

The medium infrared spectra were obtained with a Nicolet IR 200 spectrometer from Thermo Scientific in attenuated total reflectance mode (FTIR-ATR). Each spectrum was obtained from an average of 32 scans in the range of 4000 to 650 cm–1, with a resolution of 4 cm–1.

Oxidative Stability

The procedure used to determine oxidative stability was the one described in the European Standard 14112. The equipment used in the tests was the biodiesel Rancimat 873 (Metrohm). According to the method described, 3 g of the sample are oxidized by an airflow (10 L/h at 110 °C) in a measuring cell supplied with distilled water. The induction period was determined by measuring the conductivity. The experiments were carried out in at least duplicate.

Multivariate Data Analysis

All spectra were submitted to multivariate analysis using tools such as principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA). The PCA and HCA models were built using the Unscrambler X software. The data were pre-processed with a combination of a Savitzky–Golay smoothing filter with a 7-point window, baseline correction, and mean-centered data.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to FAPEMA and CNPq for financial support. The research facilities for this work provided by IFMA and UFMA are also gratefully acknowledged.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Knothe G.; Krahl J.; Gerpen J. H.. The Biodiesel Handbook; 2nd ed.; Campaign, Illinois; AOCS Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Encinar J. M.; Gonzalez J. F.; Rodríguez-Reinares A. Ethanolysis of used frying oil. Biodiesel Preparation and Characterization. Fuel Process. Technol. 2007, 88, 513–522. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2007.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yogeeswara T.; Devendra U.; Kalaisselvane A. Physical and chemical characterization of waste frying palm oil biodiesel and its blends with diesel. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2225, 030003. [Google Scholar]

- Canakci M.; Van Gerpen J. Biodiesel production from oils and fats with high free fatty acids. Trans. ASAE 2001, 44, 1429–1436. 10.13031/2013.7010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dias J. M.; Alvim-Ferraz M. C.; Almeida M. F. Mixtures of vegetable oils and animal fat for biodiesel production: influence on product composition and quality. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 3889–3893. 10.1021/ef8005383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fattah I. R.; Masjuki H. H.; Kalam M. A.; Hazrat M. A.; Masum B. M.; Imtenan S.; Ashraful A. M. Effect of antioxidants on oxidation stability of biodiesel derived from vegetable and animal based feedstocks. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 356–370. 10.1016/j.rser.2013.10.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W.; Wan F. Immobilization of polyoxometalate-based sulfonated ionic liquids on UiO-66-2COOH metal-organic frameworks for biodiesel production via one-pot transesterification-esterification of acidic vegetable oils. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 365, 40–50. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W.; Wang H. Immobilized polymeric sulfonated ionic liquid on core-shell structured Fe3O4/SiO2 composites: A magnetically recyclable catalyst for simultaneous transesterification and esterifications of low-cost oils to biodiesel. Renewable Energy 2020, 145, 1709–1719. 10.1016/j.renene.2019.07.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yaakob Z.; Narayanan B. N.; Padikkaparambil S.; Unni K. S.; Akbar P. M. A review on the oxidation stability of biodiesel. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2014, 35, 136–153. 10.1016/j.rser.2014.03.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondioli P.; Gasparoli A.; Della Bella L.; Tagliabue S.; Toso G. Biodiesel stability under commercial storage conditions over one year. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2003, 105, 735–741. 10.1002/ejlt.200300783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G.; Kumar D.; Johari R.; Singh C. P. Enzymatic transesterification of Jatropha curcas oil assisted by ultrasonication. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011, 18, 923–927. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anp.gov.br. Brasília: Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis - Resolução N° 45, de 25 de Agosto de 2014 - DOU 26.08.2014.

- Karavalakis G.; Hilari D.; Givalou L.; Karonis D.; Stournas S. Storage stability and ageing effect of biodiesel blends treated with different antioxidants. Energy 2011, 36, 369–374. 10.1016/j.energy.2010.10.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schober S.; Mittelbach M. The impact of antioxidants on biodiesel oxidation stability. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2004, 106, 382–389. 10.1002/ejlt.200400954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. Y.; Kim D. K.; Lee J. P.; Park S. C.; Kim Y. J.; Lee J. S. Blending effects of biodiesels on oxidation stability and low temperature flow properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1196–1203. 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H.; Wang A.; Salley S. O.; Simon K. Y. The effect of natural and synthetic antioxidants on the oxidative stability of biodiesel. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2008, 85, 373–382. 10.1007/s11746-008-1208-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Supriyono; Sulistyo H.; Almeida M. F.; Dias J. M. Influence of synthetic antioxidants on the oxidation stability of biodiesel produced from acid raw Jatropha curcas oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 132, 133–138. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rial R. F.; Freitas O. N.; dos Santos G.; Nazário C. E. D.; Viana L. H. Evaluation of the oxidative and thermal stability of soybean methyl biodiesel with additions of dichloromethane extract ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Renewable Energy 2019, 143, 295–300. 10.1016/j.renene.2019.04.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; He Q. S.; Corscadden K.; Caldwell C. Improvement on oxidation and storage stability of biodiesel derived from an emerging feedstock camelina. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 157, 90–98. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2016.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller D.; Ferrão M. F.; Marder L.; Da Costa A. B.; Schneider R. C. S. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and multivariate analysis for identification of different vegetable oils used in biodiesel production. Sensors 2013, 13, 4258–4271. 10.3390/s130404258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos V. H. J. M.; Bruzza E. D. C.; De Lima J. E.; Lourega R. V.; Rodrigues L. F. Discriminant Analysis and Cluster Analysis of Biodiesel Fuel Blends Based on Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 4905–4915. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b00447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.; Irudayaraj J.; Paradkar M. M. Discriminant analysis of edible oils and fats by FTIR, FT-NIR and FT – Raman spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2005, 93, 25–32. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.08.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balabin R. M.; Safieva R. Z. Biodiesel classification by base stock type (vegetable oil) using near infrared spectroscopy data. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 689, 190–197. 10.1016/j.aca.2011.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focke W. W.; Westhuizen I. V. D.; Oosthuysen X. Biodiesel oxidative stability from Rancimat data. Thermochim. Acta 2016, 633, 116–121. 10.1016/j.tca.2016.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa L. S.; de Moura C. V. R.; de Moura E. M. Action of natural antioxidants on the oxidative stability of soy biodiesel during storage. Fuel 2021, 288, 119632 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.; Cunshan Z.; Vittayapadung S.; Xiangqian S.; Mingdong D. Opportunities and challenges for biodiesel fuel. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 1020–1031. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.09.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archile A.; Benitez B.; Rangel L.; Izquierdo P.; Huerta Leidenz N.; Márquez Salas E. J. Perfil de ácidos grasos de las principales grasas y aceites desponibles para consume en la ciudad de Maracaibo. Revista Cientifica 1997, 07, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Gerpen J.V.; Shanks B.; Pruszko R.. Biodiesel Production Technology; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden (Colorado), 2004, 01–105. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy04osti/36244.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Meira M.; Quintella C. M.; Tanajura Ados S.; Fernando J. D.; da Costa Neto P. R.; Pepe I. M.; Santos M. A.; Nascimento L. L. Determination of the oxidation stability of biodiesel and oils by spectrofluorimetry and multivariate calibration. Talanta 2011, 85, 430–434. 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva F. A.; Borges M. F. M.; Ferreira M. A. Métodos para avaliação do grau de oxidação lipídica e da capacidade antioxidante. Química Nova 1999, 22, 94–103. 10.1590/S0100-40421999000100016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martini W. S.; Porto B. L. S.; de Oliveira M. A. L.; Sant’Ana A. C. Comparative Study of the Lipid Profiles of Oils from Kernels of Peanut, Babassu, Coconut, Castor and Grape by GC-FID and Raman Spectroscopy. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2018, 29, 390–397. 10.21577/0103-5053.20170152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. T.; Foglia T. A. Synthesis, purification, and characterization of structured lipids produced from chicken fat. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2000, 77, 1027–1034. 10.1007/s11746-000-0163-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varatharajan K.; Pushparani D. S. Screening of antioxidant additives for biodiesel fuels. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2017–2018. 10.1016/j.rser.2017.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kachel M.; Matwijczuk A.; Przywara A.; Kraszkiewicz A.; Koszel M. Profile of Fatty Acids and Spectroscopic Characteristics of Selected Vegetable Oils Extracted by Cold Maceration. Agric. Eng. 2018, 22, 61–71. 10.1515/agriceng-2018-0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buiatte J. E.; Guimarães E.; Mitsutake H.; Gontijo L. C.; Santos D. Q.; Neto W. B. Qualitative and Quantitative Monitoring of Methyl Cotton Biodiesel Content in Biodiesel/Diesel Blends Using MIR Spectroscopy and Chemometrics Tools. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2016, 27, 84–90. 10.5935/0103-5053.20150251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van de Voort F. R.; Ismail A. A.; Sedman J.; Emo G. Monitoring the oxidation of edible oils by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1994, 71, 243–253. 10.1007/BF02638049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feddern V.; Kupski L.; Cipolatti E.; Giacobbo G.; Mendes G.; Badiale-Furlong E.; Souza-Soares L. Physico-chemical composition, fractionated glycerides and fatty acid profile of chicken skin fat. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2010, 112, 1277–1284. 10.1002/ejlt.201000072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino I.; Hernandez R.; Chicoma D.; Pinto H.; Aoki I. Influence of light, temperature and metallic ions on biodiesel degradation and corrosiveness to copper and brass. Fuel 2012, 102, 795–807. 10.1016/j.fuel.2012.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. W.; Tsai S. W. Production of biodiesel from chicken wastes by various alcohol-catalyst combinations. J. energy South. Afr. 2015, 26, 36–45. 10.17159/2413-3051/2015/v26i1a2219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]