Abstract

The FeVco cofactor of nitrogenase (VFe7S8(CO3)C) is an alternative in the molybdenum (Mo)-deficient free soil living azotobacter vinelandii. The rate of N2 reduction to NH3 by FeVco is a few times higher than that by FeMoco (MoFe7S9C) at low temperature. It provides a N source in the form of ammonium ions to the soil. This biochemical NH3 synthesis is an alternative to the industrial energy-demanding production of NH3 by the Haber–Bosch process. The role of vanadium has not been clearly understood yet, which has led chemists to come up with several stable V–N2 complexes which have been isolated and characterized in the laboratory over the past three decades. Herein, we report the EDA–NOCV analyses of dinitrogen-bonded stable complexes V(III/I)–N2 (1–4) to provide deeper insights into the fundamental bonding aspects of V–N2 bond, showing the interacting orbitals and corresponding pairwise orbital interaction energies (ΔEorb(n)). The computed intrinsic interaction energy (ΔEint) of V–N2–V bonds is significantly higher than those of the previously reported Fe–N2–Fe bonds. Covalent interaction energy (ΔEorb) is more than double the electrostatic interaction energy (ΔEelstat) of V–N2–V bonds. ΔEint values of V–N2–V bonds are in the range of −172 to −204 kcal/mol. The V → N2 ← V π-backdonation is four times stronger than V ← N2 → V σ-donation. V–N2 bonds are much more covalent in nature than Fe–N2 bonds.

Introduction

Nitrogen is one of the most important and essential elements for microorganisms, plants, and animals.1,2 Dinitrogen (N2) is the major component of the earth atmosphere (78%). All of these can breathe air but cannot directly utilize dinitrogen (N2) from the inhaled gas and hence have to expel it as is without converting it to other forms of N compounds in their cell except for a few organisms like rhizobium, azotobacter, etc.1 These bacteria have developed a variety of species genomes, which can form different protein-containing enzymes such as nitrogenase, which can nurture protein-encapsulated inorganic metal complexes such as P clusters, 4Fe–4S, and FeMoco/FeVco cofactors in oxygen free environments.2 The evolution of FeMoco, FeVco, and FeFeco in sea water via genetic analyses has been recently summarized.3 FeVco and FeFeco have been less extensively studied compared to FeMoco. However, it has been concluded that FeVco needs more electrons to produce similar equivalents of NH3 since it also produces more H2 gas. Very recently, the structural aspects of FeVco have been confirmed with a 1.35 Å structure of vanadium nitrogenase from azotobacter vinelandii.4 Combined with sunlight and Mg–ATM, nitrogenase can direct the electron carriers P clusters, 4Fe–4S, and ferredoxin to transport required numbers of electrons to the FeMoco/FeVco cofactors (Scheme 1) within the nitrogenase with some conformational changes in the protein folding, bringing them closer to facilitate the electron transfer to the inorganic core of FeMoco/FeVco cofactors.1,2 The most common nitrogenase cofactor is FeMoco,5 which is actually an anionic heterobimetallic coordination cluster MoFe7S9C1– containing a μ6-C atom in the center of it.6,7 This light element (C) bridges between six mixed-valence Fe ions, which are antiferromagnetically coupled via μ-S2– and μ6-C4– bridges. FeMoco possesses two heterocubanes Fe4S4 and MoFe3S3, which are connected via three μ-S2– and μ6-C4– bridges.6,7 Until now, the exact mode of N2 binding, activation, and mode of the reduction of N2 to NH3 have not been confirmed.1 Kinetic studies showed that N2 binding is most likely at one of the Fe ions of the (μ6-C4–)Fe6 unit. Further studies showed that a similar vanadium analogue of FeMoco (MoFe7S9C) can do a similar job in the Mo-deficient soil, which is known as FeVco.3,4 The structural analyses of vanadium nitrogenase obtained from azotobacter vinelandii showed that one of the belt sulfide ions is replaced by a carbonate anion having different proteins to adopt this carbonate anion to fit in the cavity.4 Over the last four decades, several Mo, V, and Fe ion-containing complexes have been synthesized, isolated, and characterized, containing stable Mo/V/Fe–N2 bonds.8−29 Some of these complexes have been stepwise reduced with electrons and subsequent addition of protons, and the corresponding intermediate species have been even isolated and characterized too. The M → N2 π-backdonations and elongation of N–N bond have been discussed from density functional theory (DFT) calculations, WBI values, and NBO analyses.21−23,30−34 However, the nature and strength of σ/π M ← N2/M → N2 donation/backdonations and exact orbitals involved in bonding have been rarely studied until very recently for M=Fe.35,37 There are over 20 reports9−29 purely on V–N2-containing systems, and there are several mixed vanadium and other metals containing end-on N2 bridges. A distinct feature has been observed for V–N2−V complexes. V(III) or V(I) complexes with end-on N2 bridges possess a diamagnetic ground state, while Fe–N2–Fe complexes are paramagnetic/diamagnetic in nature. It is hence suspected that the nature of bonding interaction between V and N2 is quite different and possibly very strong where a strong antiferromagnetic coupling11−22 is mediated via an end-on N2 bridge or has something to do with the electron pairing due to the chemical bonding.22 The DFT calculations of the V(II)–N2–V(II) complex22 showed that due to V → N2 ← V π-backdonation (π*) interactions, the V(dxy) + N2(π*) and V(dyz) + N2(π*) orbitals became lower in energy, accommodating two pairs of electrons from two V(III) (d2) ions, leading to a S = 0 spin ground state.22 The geometry optimization and theoretical calculations involving vanadium ions is quite challenging too.21−23 However, a V(II)–N2–V(II) complex has been shown to have a diamagnetic singlet spin ground state (S = 0) with a suggested canonical structure V(III)–N22––V(III), which has been concluded from DFT calculations and computation of Mulliken spin densities.23 V(III)–N22––V(III) has been suggested to have antiferromagnetic coupling between two V(III) centers having the lower energy dz2 and dx2–y2 orbitals with electrons on each V(III) ion.23

Scheme 1. Nitrogenase Cofactors P Cluster (a, b), [4Fe–4S] (c), and FeVco (d) Cofactors of the Nitrogenase Enzyme.

The most crucial step for activation of dinitrogen with binding of a transition metal complex is the weakening of the strong N ≡ N bond by π-backdonation (M → N2) from metal into antibonding molecular orbitals of N2. CH3C[(CH2)N(i-Pr)Li]3 or TIAME and VCl3(THF)3 react to form the dinitrogen complex (TIAME)V–N2–V(TIAME) (1) containing an end-on bridging N2 molecule.11 In the presence of nitrogen, the reaction of VCl3(THF)3 with three moles of Me3CCH2Li in diethylether produces the bridging nitrogen complex [(Me3CCH2)3V]2(μ-N2) (2).12 When VCl3(THF)3 is suspended in THF and treated with lithium di-isopropyl-amide (LDA), it forms the bridge dinitrogen complex [((i-Pr)2N)3V]2(μ-N2) (3).13 When [5,1-(C5H4CH2CH2NMe2)VCl2(PMe3)] is reduced under a nitrogen atmosphere in the presence of diphenylacetylene, a bridging dinitrogen complex {[5-(C5H4CH2CH2NMe2)]V(PhC≡CPh)(PMe3)2}2(μ-N2) (4) is formed.14 All four complexes possess a singlet (diamagnetic) spin ground state. These complexes have not been previously studied by theoretical calculations. For these complexes, the V–N bond length is between 1.704 and 1.767 Å, and the N–N bond length is in the range of 1.204–1.280 Å. The N2 unit in these compounds has a longer N–N bond length than a free N2 molecule (1.102 Å), which is due to the effect of V→N2 π-backdonation corresponding to N−N bond activation.11−14 When complex (2) is protonated with HCl, instead of hydrazine or ammonia, neopentane is produced. Due to a sterically packed ligand, neopentyl is protonated instead of nitrogen, generating neopentane.12 It prompted us to look into the bonding characteristics of these complexes. Herein, we report on the DFT, QTAIM calculations, and EDA–NOCV analyses of these four diamagnetic complexes (1–4) possessing an end-on μ-bridging N2 molecule to shed light on the V–N2 bonding with the computations of intrinsic interaction energy (ΔEint) and pairwise orbital interaction energy of the V–N2–V bonds. The formal oxidation states of V ions are +3 (1–3) and +1 (4), respectively.

Results and Discussion

In addition to the literature review,8−29 we used computational methods such as optimization, NBO, QTAIM, and EDA–NOCV to investigate the geometrical parameters and bonding nature of the complexes (see Scheme 2). Our calculations were done at the BP86-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVPP level of theory. We also checked that the geometrical parameters computed at the BP86 and TPSS levels of theory are very similar (see SI).

Scheme 2. Previously Reported Modeled Complexes Containing N2 as a Bridged Ligand between Two Vanadium Metal Centers.

For the complexes presented in Scheme 2, we carried out geometry optimization and vibrational frequency computations in singlet and triplet electronic states. Complexes 1–4 are more stable in their singlet states11−14 than their triplet states by 16.0–35.9 kcal/mol.

Each V atom of complexes 1–3 adopts11−13 a pseudotetrahedral coordination geometry with a N4 or C3N donor set. Two V(III/I) centers are connected/bridged by a 1,2-μ-N2 (end-on) molecule. The coordination geometry of the V center in 4 appears14 to be similar although it is bonded to a η5-cp ring and a C≡C triple bond of diphenylacetylene. The CPh–C–C–CPh torsion angle (4.4°) in 4 is significantly lower than that of a free diphenylacetylene ligand, suggesting a significant charge flow from the V(I) center to the acetylene triple bond via V → C≡C (side-on) π-backdonation. Two phenyl groups are cis to each other. Two N atoms of the amino group attached to the cp ring are not bonded to the V(I) centers of 4. Six neopentyl tBu groups are oriented toward the bridging N≡N unit, shielding this core. The V–N2 bond lengths of complexes 1–4 in their optimized geometries, as shown in Figure 1, lie in the range of 1.705–1.765 Å, which are very similar to those of the experimentally observed V–N2 bond length (1.704–1.767 Å)1−4 obtained from X-ray single-crystal diffraction (Figure 1). The V–N2 bond lengths in 1–4 are significantly different than that of the rarely isolated stable V≡N complex (1.565(4) Å).23 The V−NN2 bond lengths are in the order 1 < 2 < 3 < 4. The significant backdonation from metal to nitrogen causes the shorter bond lengths in complexes 1–3 when these values are compared with that (1.103) of the free N2 molecule.11−14

Figure 1.

Optimized geometries of complexes 1–4 at the BP86-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVPP level of theory at their singlet states. Bond lengths are in Å and bond angles are in degree (°). Nitrogen atoms are represented with blue spheres, vanadium metal atoms with violet spheres, and carbon atoms with gray-colored spheres. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

In complex 1,11 there is a strong backdonation from metal to nitrogen, which could be due to the donation of a lone pair of electrons from the nitrogen atom of the TIAME ligand to vanadium. It causes an increase in electron density in vanadium, enabling more electron backdonation from vanadium to the dinitrogen unit of the complex, consequently shortening the bond. Although the same thing can happen in complex 3,13 namely, the transfer of a lone pair of electrons from a diisopropylamide’s nitrogen atom to the vanadium metal. However, the donation may not be as strong as in complex 3 due to waging nature of a iPr substituent in three noncyclic N(iPr2) ligands (3), whereas in complex 1, the ligand is directionally chelating, resulting in stronger donations of electron densities of lone pair of electrons of adjacent N atoms in complex 1 as opposed to complex 3. Due to the nonchelating nature of the ligand in complex 3, backdonation from vanadium metal to the nitrogen ligand is likely to be less than that in complex 2,12 resulting in a longer V–N2 bond length in complex 3. Note that the formal oxidation states of 1–3 and 4 are +3 and +1, respectively. The formal charges on the V metals may also be the reason for different V–N bond lengths. It is apparent that due to the poor backdonation from vanadium metal to the dinitrogen ligand, the V–N2 bond length in complex 4 is longer than those of the other three complexes 1, 2, and 3. The PMe3 and acetylene ligands, which are known as π-acceptor ligands, also compete for V → PMe3/acetylene π-backdonations. As a result, the effective share of electron densities reduces, possibly resulting in a lesser extent of π-backdonation to the dinitrogen ligand from vanadium. As a result, the V–N2 bond length is slightly longer in complex 4 than those of the other complexes. The N–N bond length follows the order 4 < 3 < 2 < 1.11−14 However, their values are very close to each other, 1.215–1.246 Å, which are slightly different than experimentally reported N–N bond lengths (1.204–1.280 Å).11−14 These differences can be attributed to the solvation and/or intermolecular forces in solid states.35b The V–N–N bond angle measured for these complexes is nearly equal to 180°, implying that four atoms, two vanadium atoms, and two nitrogen atoms of the N2 unit are linearly bonded.

The V–N bond dissociation energy, as shown in Table 1, of these complexes is found to be in the order 1 (De = +110.48 kcal/mol) > 2 (De = +102.78 kcal/mol) > 3 (De = +88.64 kcal/mol) > 4 (De = +79.38 kcal/mol), which is expected after observing that the V–N bond length and the dissociation of the N2 unit is endergonic (Table 2(1)) and follow the same order as that of the V–N bond dissociation energy, i.e., 1 (ΔG = +82.70 kcal/mol) > 2 (ΔG = +67.12 kcal/mol) > 3 (ΔG = +50.92 kcal/mol) > 4 (ΔG = +48.29 kcal/mol). The endergonicity of dissociation of the N2 unit is the highest in 1, followed by 2 and 3, and the lowest in 4, which indicates that complex 1 is thermodynamically more stable than complexes 2, 3, and 4. The energy gap between FMO (frontier molecular orbitals), i.e., the energy gap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) (ΔH–L), can also be used to evaluate a system’s electronic stability. For these species, the HOMO–LUMO energy gap follows the order 1 (ΔH–L = 2.077 eV) > 2 (ΔH–L = 1.991 eV) > 3 (ΔH–L = 1.836 eV) > 4 (ΔH–L = 1.470 eV) suggesting that complex 1 is more electronically stable and less reactive than 2, 3, and 4 based on the HOMO–LUMO energy gap (Scheme 3). This stability order could be owing to the bulky character of the ligands connected to the vanadium metal center. Chelation in a complex is an entropy-friendly process. As we move on from complex 2 to complex 4, the bulkiness of the ligand increases, causing complex 4 to lose stability. As a result, we can deduce that the HOMO–LUMO energy gap of a complex reduces as the bulky nature of the ligand increases.22,23

Table 1. Dissociation Energy (V−N2−V Bonds) and Gibbs Free Energy of Dissociation of N2 in the Complexes at the BP86-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVPP Level of Theorya.

| complex | dissociation energy, De (kcal/mol) | Gibbs energy, ΔG (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 110.48 | 82.70 |

| 2 | 102.78 | 67.12 |

| 3 | 88.64 | 50.92 |

| 4 | 79.38 | 48.29 |

Energy is given in kcal/mol.

Table 2. NBO Analysis of Complexes 1–4 at the BP86-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVPP Level of Theorya.

| complex | bond | ON | polarization and hybridization (%) | WBI | q(N2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | V–N σ | 1.95 | V: 22.50% s(31.6%), p(13.2%) d(55.2%) | N: 77.50% s(63.6%), p(36.4%) | 1.70 | –0.312 |

| V–N π | 1.74 | V: 28.66% p(29.1%), d(70.9%) | N: 71.34% p(99.96%) | |||

| V–N π | 1.75 | V: 29.13% p(27.4%), d(72.6%) | N: 70.87% p(99.96%) | |||

| N–N σ | 1.97 | N: 50.22% s(36.3%), p(63.7%) | N: 49.78% s(35.2%), p(64.8%) | 1.500 | ||

| 2 | V–N σ | 1.96 | V: 20.5% s(25.3%), p(12.8%), d(61.9%) | N: 79.5% s(63.8%), p(36.2%) | 1.67 | –0.415 |

| V–N π | 1.80 | V: 31.7% p(3.8%), d(96.2%) | N: 68.3% p(100.0%) | |||

| V–N π | 1.80 | V: 31.7% p(3.8%), d(96.2%) | N: 68.3% p(100.0%) | |||

| N–N σ | 1.98 | N: 50.0% s(36.1%), p(63.9%) | N: 50.0% s(36.1%), p(63.9%) | 1.52 | ||

| 3 | V–N σ | 1.92 | V:15.7% s(25.0%), p(31.4%), d(43.6%) | N: 84.3% s(64.7%), p(35.3%) | 1.48 | –0.638 |

| V–N π | 1.78 | V: 31.5% p(17.0%), d(83.0%) | N: 68.5% p(100.0%) | |||

| V–N π | 1.69 | V: 22.2% p(36.0%), d(64.0%) | N: 77.8% p(100.0%) | |||

| N–N σ | 1.98 | N: 50.0% s(34.9%), p(65.1%) | N: 50.0% s(34.9%), p(65.1%) | 1.52 | ||

| 4 | V–N | 1.53 | –0.001 | |||

| N–N | 1.73 | |||||

There was no solvent media included. Wiberg bond indices (WBI), polarization, hybridization of distinct bonds, occupation number (ON), and partial charges (q).

Scheme 3. Effect on the HOMO–LUMO Energy Gap on Changing the Ligand Coordinated to the Vanadium Metal Center from Complexes 1–4.

To determine the nature of chemical bonding and orbital interaction of these complexes, we used energy and charge density methods such as NBO, QTAIM, and EDA–NOCV to perform quantum chemical computations. Figure 2 shows the orbital images of these complexes from the NBO calculations performed at the BP86-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVPP level of theory. The Wiberg bond indices (WBI) of the N–N bond for these complexes are in the range of 1.50–1.73 Å, which are significantly smaller than that of the free N2 molecule (3.03), suggesting the transfer of a significant amount of charge densities from V(III/I) → N2 π-backdonation. The WBI values of the N–N bonds in these complexes are in the sequence 1 > 2 = 3 > 4, suggesting that complex 1 possesses higher π-backdonation than complexes 2, 3, and 4. The WBI values for corresponding V–N2 bonds are in the range of 1.48–1.70 (Table 2). These V–NN2 bonds are significantly polarized toward N2 due to differences in their electronegativity values. The NBO analyses revealed an accumulation of electron/charge densities (−0.638 to −0.001) on the N2 units of 1–4, again suggesting that vanadium to dinitrogen (V → N2) π-backdonations are stronger than V ← N2 σ-donations. In complex 4, there is a negligible charge accumulation on the N2 unit. The computed NPA charges are 0.504 (1), 0.711 (2), and 0.885 (3) on each vanadium, and −0.687 and −0.681 on two V atoms of 4.

Figure 2.

NBOs of complexes 1–4 at the BP86-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVPP level of theory.

The BCP at the (3, −1) topological point (bond critical point; small green sphere) in the Laplacian of the electron density contour plot of these complexes (1–4), shown in Figure 3, is directed away from the center of the bond, indicating that the bond is slightly polarized (Figure 4), which is compatible with the NBO analysis. The V–NN2 bond is polarized toward the N atom of the N2 unit, according to NBO analysis, due to higher π-backdonation from vanadium to nitrogen (V → N2) than σ-donation from nitrogen to vanadium (V → N2). The electron density is concentrated on the nitrogen atom in these complexes, as demonstrated by the contour plot shown in Figure 3, which is in good agreement with the charge concentration revealed by the NBO analysis. There is a bond parameter, called bond ellipticity (ε = λ1/λ2–1), where λ1 and λ2 are the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix, which measure the deviation of the distribution of electron densities from the cylindrical shape as a measure of the bond order. If the bond ellipticity value at BCP (3, −1) εBCP is close to zero, then the bond will be either a single or a triple bond due to the cylindrical contours of electron density (ρ(r)) along the bond path, but if the εBCP is greater than zero, then the bond will be a double bond. The bond ellipticity value (εBCP) for the V–NN2 bond of these complexes is given in Table 2(3), which lies in the range of 0.000–0.177.

Figure 3.

For V–N–N–V, a contour plot of the Laplacian distribution [∇2ρ(r)] in complexes 1–4 is given. The charge concentration (∇2ρ(r) < 0) is depicted by blue solid lines, while charge depletion (∇2ρ(r) > 0) is depicted by red dotted lines. The small green sphere represents the bond critical point (BCP) along the bond path, and the thick solid blue lines linking the atomic basins depict the zero-flux surface crossing the molecular plane. Nitrogen atoms are symbolized by blue atoms, while vanadium atoms are symbolized by pink atoms.

Figure 4.

MEP surface plots of complexes 1–4 in Cartesian coordinates calculated with DFT at the BP86-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVPP level of theory. Electronegative regions are shown in various colors. The minimum electrostatic potential (i.e., more electron charge density) is depicted in red, while the maximum electrostatic potential (i.e., less electron charge density) is depicted in dark blue. Yellow and light blue show the intermediate.

Table 2 does not include the occupancy of the V–NN2 bond and the N–N bond of complex 4 because NBO computations were unable to determine these values as they were lower than the threshold occupancy. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface plots of these complexes’ positively and negatively charged electrostatic potential are shown in Figure 4.

The triple bond between vanadium and nitrogen in the N2 unit is confirmed by NBO analysis. Table 3 further shows that the bond ellipticity value (BCP) for these complexes’ N–N bond is very near to zero, indicating the possibility of either a single or a triple bond. The single bond between two nitrogen atoms in N2 is confirmed by the NBO analysis. The parameter η, which can be computed using the ratio |λ1|/λ3, where λ1 and λ3 are the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix, represents the bond type and softness. If the number is less than 1.0, it implies closed-shell interactions, as the electron density shrinks away from the BCP for these interactions. If the value is more than 1, then the bond is said to be covalent. The η value for the V–N bond is in the range of 0.174–0.196, which is less than 1.0, signifying that these bonds are formed via closed-shell interactions. The fact that the value for the N–N bond is greater than 1.0 and falls between 1.172 and 2.496 suggests the covalent nature of the N–N bond. The covalent character of the N–N bond is further shown by the relatively high electron density ρ(r) and total energy density H(r) near the bond critical point (BCP). The positive Laplacian of BCP electron density, ∇2ρ(r), and the relatively lower electron density ρ(r) at BCP (Table 3) of V–N show that charge is ejected from that region, covalency is weak, and electrostatic interactions are present. The negative Laplacian of BCP electron density, ∇2(r), for the N–N bond of these complexes implies shared interaction between two N atoms of the N2 unit (Table 3). The higher the electron density is at the bond critical point, the stronger the bond. Table 2(3) shows that the V–NN2 bond strength of the complexes is in the order 1 ≈ 2 > 3 > 4, which is consistent with the V–N bond dissociation energy given in Table 1, and the electron density at BCP for the N–N bond of these complexes is in the order 1 < 2 < 3 < 4, indicating that the N–N bond strength follows the same order as the V–NN2 bond dissociation energy. The ratio |2G(r)/V(r)| also provides details of the nature of interactions. If the value is less than 1, the interaction is covalent. If the −G(r)/V(r) ratio is greater than 1.0, the interaction is totally noncovalent. Table 3 shows that for these complexes, the ratio |2G(r)/V(r)| for the N–N bond is smaller than 1.0, indicating that the interaction between two N atoms is covalent.

Table 3. Electron Density (ρ(r)), Laplacian (∇2ρ(r)), Total Energy Density (H(r)), Potential Energy Density (V(r)), Kinetic Energy Density (G(r)), Ellipticity (εBCP), and Eta (η) Values from AIM Analysis of Complexes 1–4 (Singlet State)a.

| complex | bond | ρ(r) | ∇2ρ(r) | H(r) | V(r) | G(r) | εBCP | η | |2G(r)/V(r)| | –G(r)/V(r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | V–N | 0.181 | 0.902 | –0.074 | –0.374 | 0.300 | 0.000 | 0.174 | 1.604 | 0.802 |

| N–N | 0.463 | –1.267 | –0.616 | –0.914 | 0.298 | 0.000 | 1.172 | 0.652 | 0.326 | |

| 2 | V–N | 0.182 | 0.886 | –0.075 | –0.372 | 0.297 | 0.000 | 0.183 | 1.597 | 0.798 |

| N–N | 0.471 | –1.306 | –0.633 | –0.940 | 0.307 | 0.000 | 2.496 | 0.653 | 0.326 | |

| 3 | V–N | 0.171 | 0.864 | –0.064 | –0.345 | 0.281 | 0.129 | 0.185 | 1.629 | 0.814 |

| N–N | 0.474 | –1.306 | –0.640 | –0.953 | 0.313 | 0.004 | 1.186 | 0.657 | 0.328 | |

| 4 | V–N | 0.157 | 0.788 | –0.052 | –0.301 | 0.249 | 0.177 | 0.196 | 1.654 | 0.827 |

| N–N | 0.503 | –1.452 | –0.710 | –1.057 | 0.347 | 0.010 | 1.249 | 0.656 | 0.328 |

Values are in a.u.

It has been established that NBO and QTAIM often may not be able to accurately provide the nature of chemical bonds and orbital involved in the formation of the chemical bonds of interest. We investigated the V–N2 bond of complexes 1–4 by EDA–NOCV (energy decomposition analyses coupled with natural orbital for chemical valence)50,51,56−60 analyses to estimate the intrinsic interaction energy (ΔEint) and pairwise orbital interaction energies to shed light on the nature of the metal–dinitrogen bond. EDA–NOCV calculations (one complex (4); see SI) showed that the nature of the bonds between V and N2 are dative σ/π-bonds rather than electron-sharing σ/π-bonds. The ((L)V)2 and N2 fragments prefer to form bonds in their singlet states rather than in quintet states, which has been confirmed from the lower absolute value of orbital interaction energy (ΔEorb).

L = TIAME (1), (Me3CCH2)3 (2), ((iPr)2N)3 (3), {η5-(C5H4CH2CH2NMe2)}(PhC≡ CPh)(PMe3) (4).

The interaction energy (ΔEint) of the complexes 1–4 lies between −172.1 and −204.0 kcal/mol in the order 1 > 2 > 3 > 4, suggesting that the ΔEint values of V(III)–N2–V(III) bonds in 1–3 are significantly higher than those of V(I)–N2–V(I) bonds in 4. Note that 4 possesses an olefin bonded to each V(I) center. The V–N2 bond dissociation energies (De) of 1–4 are in the range of 79–110 kcal/mol having an order of 1 > 2 > 3 > 4 (Table 1). The De of the V–N2−V bond in 1 is higher by 30 kcal/mol that that of 4, which could be partially due to the competitive V–olefin interactions in 4. The interaction energy is larger than the dissociation energy of the V–N2−V bond (Table 1). The interactions energy (ΔEint) (−116.9 kcal/mol)35a of Fe(I)–N2–Fe(I) bonds36 previously reported singlet diiron–N2 complex is significantly lower than those of V(III/I)–N2–V(III/I) bonds in 1–4 (−172.1 and −204.0 kcal/mol). The V → N2 ← V π-backdonation is four times stronger than V ← N2 → V σ-donation. V–N2 bonds are much more covalent in nature than Fe–N2–Fe bonds.35a,36

This difference arises due to the preparative energy, which requires fragment preparation energy and additional energy for electronic excitation to the reference spin energy states of all of the fragments. The attractive dispersion energies of two V–N2 bonds of 1–4 are approximately 2–3% of the total interaction energy. The average Pauli repulsion energy (ΔEPauli) of 1–4 is nearly 65% of the overall attractive interaction energies, following the order 1 > 2 > 3 > 4. The contribution due to the electrostatic interaction energies (ΔEelstat) and orbital interaction energies (ΔEorb) between 2(L)V(III/I) and N2 fragments to the overall ΔEint in 1–4 is in the range of ∼27–33 and ∼63–71%, respectively, suggesting that the latter is 2.5 times higher than the former. The V–N2 bonds of 1–4 are dominated by covalent interactions, which decrease in the order 1 < 2 < 3 < 4 (Table 4).

Table 4. EDA–NOCV Results at the BP86-D3(BJ)/TZ2P Level of V–N2 Bonds of (LV)2(μ-N2) Complexes 1–4 Using Neutral (LV)2 in the Electronic Singlet State and Neutral N2 Fragments in the Electronic Singlet State as Interacting Fragmentsa.

| energy | interaction | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔEint | –204.0 | –204.9 | –196.6 | –172.1 | |

| ΔEPauli | 393.29 | 357.7 | 339.6 | 332.2 | |

| ΔEdispb | –13.4 (2.2%) | –14.09 (2.5%) | –15.0 (2.8%) | –15.1 (3.0%) | |

| ΔEelstatb | –160.6 (26.9%) | –164.9 (29.3%) | –167.4 (31.2%) | –167.6 (33.2%) | |

| ΔEorbb | –423.3 (70.9%) | –383.6 (68.2%) | –353.8 (66.0%) | –321.4 (63.8%) | |

| ΔEorb(1)c | (LV)2 ← N2(3σg+) σ e– donation | –40.7 (9.6%) | –42.3 (11.0%) | –35.6 (10.1%) | –33.7 (10.5%) |

| ΔEorb(2)c | (LV)2 ← N2(2σu+) σ e– donation | –26.0 (6.2%) | –26.2 (6.8%) | –23.1 (6.5%) | –22.1 (6.9%) |

| ΔEorb(3)c | (LV)2 → N2(1πg) π e– backdonation | –173.8 (41.1%) | –154.8 (40.4%) | –150.4 (42.5%) | –154.8 (48.2%) |

| ΔEorb(4)c | (LV)2 → N2(1πg′) π e– backdonation | –173.8 (41.1%) | –144.7 (37.7%) | –125.3 (35.4%) | –91.3 (28.4%) |

| ΔEorb(rest)c | –9.0 (2.1%) | –4.1 (3.9%) | 19.4 (5.5%) | –19.5 (5.7%) |

Energy is given in kcal/mol.

Values in the parentheses indicate the contribution to the total attractive interaction ΔEelstat + ΔEorb+ ΔEdisp.

Values in parentheses show the contribution to the total orbital interaction ΔEorb..

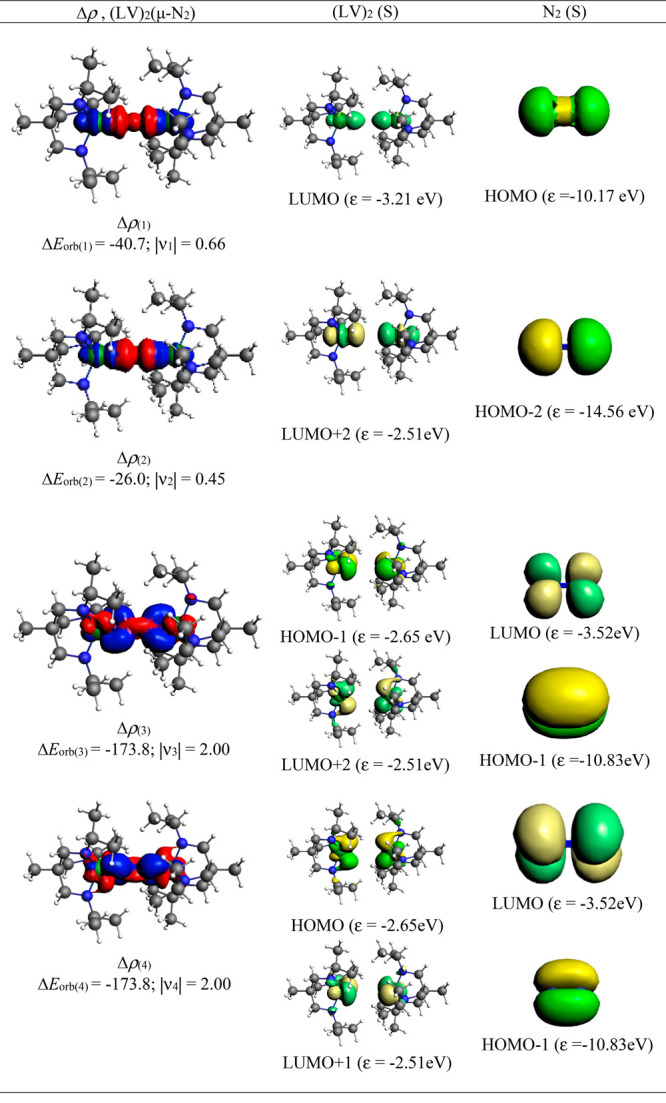

The breaking of the total orbital interaction energy (ΔEorb) into pairwise interaction energy identifies the exact orbitals on the fragments and gives pairwise stabilization energy of each set of interactions as (ΔEorb(n)) (n = 1–4). The symbols 3σg+, 2σu+, 1πg, and 1πu represent molecular orbitals σ2p–2p, σ2s–2s*, π2p–2p, and π2p–2p of N2, respectively. NOCV analyses of 1–4 revealed that there are two sets of interactions between two (L)V(III/I) and one N2 fragment: V ← N2 σ-donation (ΔEorb(1–2)) and V → N2 π-backdonation (ΔEorb(3–4)). The V ← N2 σ-donation ΔEorb(1) [(LV)2 ← N2(3σg+)] and ΔEorb(2) [(LV)2 ← N2(2σu+)] of 1–4 contribute 9–11% and 6–7%, respectively, to the total orbital interaction energy (ΔEorb). The V → N2 π-backdonation ΔEorb(3) [(LV)2 → N2(1πg)] and ΔEorb(4) [(LV)2 → N2(1πg′)] of 1–4 contribute 40–48% and 28–41%, respectively, to the total orbital interaction energy (ΔEorb). The V → N2 π-backdonation (∼75–82%) is nearly four times stronger than V ← N2 σ-donation (∼16–17%). However, ΔEorb(3)/ΔEorb(4) of 1–4 show a synergistic effect [V → N2 and V ← N2]. Figures 5–8 show how the deformation densities and related molecular orbitals reveal the direction of the charge flow for complexes 1–4.11−14 The first two orbital terms ΔEorb(1) and ΔEorb(2) represent σ-electron donation from HOMO (3σg+) and HOMO – 2 (2σu+) of N2 into vacant d-orbitals (LUMO, LUMO + 1, LUMO + 2 and LUMO + 3) of the vanadium metal center. The last two terms ΔEorb(3) and ΔEorb(4) represent the V → N2 π-backdonations from occupied d-orbitals (HOMO, HOMO – 1) of vanadium metal into the unoccupied degenerate π*-orbital LUMO (1πg and 1πg′) of dinitrogen following the order 1 > 2 > 3 > 4. However, the deformation densities (Figures 5–8) suggest the involvement of simultaneous V ← N2 π-donation (Scheme 4) [from filled bonding π-orbitals of N2 (1πu; π2p–2p) to vacant antibonding orbitals of vanadium], resulting in the increased π-contributions to the total orbital interactions. This observation from EDA–NOCV analysis explains the two π-occupancies from the NBO analysis. The shapes of the orbitals of the ((L)V)2 fragment in 1 and 3 significantly differ due to the participation of lone pairs of electrons on N atoms in π-bonding (dvanadium – pligand) with the d-orbitals of V(III) centers when they are compared with those of 2. The splitting of the two V–alkyne bonds show that intrinsic interaction energy (ΔEint) of V–alkyne is significantly higher, suggesting that V → alkyne/V ← alkyne interactions (Figure 9) are stronger than those of the V–N2 bond of 4 (Table 5). The ΔEorb(1–4) shows V ← alkyne σ-donation of 4, while the ΔEorb(5-6) represents V → alkyne π-backdonations, which are four times higher than V ← alkyne σ-donation. These competitive V−alkyne interactions may have reduced the V → N2 π-backdonations in 4; otherwise, V center of 4 being at the formal oxidation state of +1 will be able to exert N2 V → alkyne π-backdonations, leading to the lower V−N2 intrinsic interaction energy (ΔEint) when it is compared with those of 1−3.

Figure 5.

Shape of the deformation densities Δρ(1)–(4) that correspond to ΔEorb(1)–(4), and the associated MOs of (LV)2(μ-N2) (1), and the fragment orbitals of (LV)2 and N2 in the singlet state at the BP86-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level. Isosurface values of 0.003 au for Δρ(1–4). The size of the charge migration in e is determined by the eigenvalues |νn|. The direction of the charge flow of the deformation densities is red → blue.

Figure 8.

Shape of the deformation densities Δρ(1)–(4) that correspond to ΔEorb(1)–(4), and the associated MOs of (LV)2(μ-N2) (4), and the fragment orbitals of (LV)2 in the singlet state and N2 in the singlet state at the BP86-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level. Isosurface values of 0.003 au for Δρ(1–4). The size of the charge migration in e is determined by the eigenvalues |νn|. The direction of the charge flow of the deformation densities is red → blue.

Scheme 4. Orbital Interactions for the Formation of V–N2–V σ/π-Bonds in Complexes 1–4.

Figure 9.

Shape of the deformation densities Δρ(1)–(6) that correspond to ΔEorb(1)–(6), and the associated MOs of L2V2(C2Ph2)2 (1-S), and the fragment orbitals of [L2V2] in the singlet state and (C2Ph2) in the singlet state at the BP86-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level. Isosurface values of 0.001 au for Δρ(1–6) The eigenvalues νn give the size of the charge migration in e. The direction of the charge flow of the deformation densities is red → blue. ΔEorb energies are given in kcal/mol.

Table 5. EDA–NOCV Results at the BP86-D3(BJ)/TZ2P Level of L2V2–(C2Ph2)2 Bonds of (L2(C2Ph2)2)V Complex 4 Using Neutral (L2(C2Ph2)2)V in the Singlet State and Neutral C2Ph2 in the Singlet State as Fragmentsa.

| energy | interaction | [L2V2] (S) + (C2Ph2)2 (S) (4) |

|---|---|---|

| ΔEint | –239.5 | |

| ΔEPauli | 401.9 | |

| ΔEdispb | –62.3 (9.7%) | |

| ΔEelstatb | –263.1 (41.0%) | |

| ΔEorbb | –316.0 (49.3%) | |

| ΔEorb(1)c | [L2V2] ← (C2Ph2) σ e– donation | –21.8 (7.0%) |

| ΔEorb(2)c | [L2V2] ← (C2Ph2) σ e– donation | –20.3 (6.4%) |

| ΔEorb(3)c | [L2V2] ← (C2Ph2) π e– donation | –10.8 (3.4%) |

| ΔEorb(4)c | [L2V2] ← (C2Ph2) π e– donation | –8.2 (2.6%) |

| ΔEorb(5)c | [L2V2] → (C2Ph2) π e– backdonation | –118.4 (37.5%) |

| ΔEorb(6)c | [L2V2] → (C2Ph2) π e– backdonation | –115.1 (36.4%) |

| ΔEorb(rest)c | –21.4 (6.7%) |

Energy is given in kcal/mol.

Values in the parentheses show the contribution to the total attractive interaction ΔEelstat + ΔEorb + ΔEdisp.

Values in parentheses show the contribution to the total orbital interaction ΔEorb.

Figure 6.

Shape of the deformation densities Δρ(1)–(4) that correspond to ΔEorb(1)–(4), and the associated MOs of (LV)2(μ-N2) (2), and the fragment orbitals of (LV)2 and N2 in the singlet state at the BP86-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level. Isosurface values of 0.003 au for Δρ(1–4). The size of the charge migration in e is determined by the eigenvalues |νn|. The direction of the charge flow of the deformation densities is red → blue.

Figure 7.

Shape of the deformation densities Δρ(1)–(4) that correspond to ΔEorb(1)–(4), and the associated MOs of (LV)2(μ-N2) (3), and the fragment orbitals of (LV)2 and N2 in the singlet state at the BP86-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level. Isosurface values of 0.003 au for Δρ(1–4). The size of the charge migration in e is determined by the eigenvalues |νn|. The direction of the charge flow of the deformation densities is red → blue.

In conclusion, the current study elucidates the bonding and stability of experimentally reported stable vanadium–dinitrogen complexes 1–4 by employing DFT, NBO, QTAIM, and EDA–NOCV techniques. The quantum computations suggest that complexes 1–4 are more stable in the singlet state. The WBI and bond ellipticity values (from QTAIM) correlate well, suggesting a triple bond character between each vanadium and dinitrogen and a single/weak triple bond between two nitrogen atoms of the N2 unit. There is an accumulation of charge on the N2 unit, which also signifies that there is a flow of charge from vanadium to nitrogen. The NBO analysis also suggests that the V−N2−V bonds of complex 1 are stronger than those of 2, 3, and 4. The electronic stability order for the complexes is expected to be in the order 1 > 2 > 3 > 4. The η value suggests that the V–N2 bond is formed via closed-shell interactions and the N–N bond has a covalent character as expected. The NBO and QTAIM analyses both suggest that the V–N2 bond is polarized towards N2 unit due to the charge flow. The EDA–NOCV analysis predicts that the covalent character between vanadium and dinitrogen decreases from complex 1 to complex 4. It also predicts that there is stronger π-backdonation (V → N2) than the σ-donation (V ← N2) in all of the complexes and it follows the order 1 > 2 > 3 > 4; in addition, there is simultaneously π-donation from degenerate occupied HOMO – 1 (1πu and 1πu′) of dinitrogen to vacant d-orbitals of vanadium, resulting in an increase in the π-contributions to the total orbital interactions. The EDA–NOCV analyses of all four complexes (1–4) revealed that intrinsic interaction energy (ΔEint) of V–N2–V bonds (−172 to −204 kcal/mol) is significantly higher than that of the previously reported Fe–N2–Fe bonds (−116.9 kcal/mol). The V → N2 ← V π-backdonation is four times stronger than V ← N2 → V σ-donation. V–N2 bonds are more covalent in nature than Fe–N2 bonds. These results are significant from the point of view of vanadium nitrogenase (FeVco) since very little has been studied about FeVco. The N2 binding site in FeVco has not been confirmed yet. It is worth mentioning that previously reported37b cyclic Ti3(CO)3 was theoretically predicted to have σ+π aromaticity, having the cyclic Ti3 unit stabilized via entirely π-backdonation from Ti3 → (CO)3, which is remarkable.

Computational Method

Geometry optimizations and vibrational frequencies calculations of four previously reported stable dinitrogen-bonded vanadium complexes 1, 2, 3, and 4 in different spin states (singlet (S) and triplet (T)) have been carried out in the gas phase at the BP86-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVPP38−43 level using the Gaussian 16 program package.44 The NBO 6.0 program45 has been used to perform NBO analysis46,47 to evaluate natural bond orbitals, partial charges(q) on the atoms, Wiberg bond indices (WBI),48 and occupation numbers (ON). The absence of imaginary frequencies ensures the minima on the potential energy surfaces. The nature of V(III/I)–N2–V(III/I) bonds of all of the species has been analyzed by energy decomposition analysis (EDA)49 coupled with natural orbital for chemical valence (NOCV)50,51 using the ADF 2018.105 program package.55 EDA–NOCV calculations have been performed at the BP86-D3(BJ)/TZ2P52−54 level of theory utilizing the geometries optimized at the BP86-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVPP level. Generalized gradient approximations (GGAs)38−41 include both the electron density and its gradient at each point. The distribution of electron densities due to differences between the electronegativity values of an atom pair like V–N, C–V, or C–N is hence also more accurately taken care of in the GGA BP86 functional.56−60 The EDA–NOCV method involves the decomposition of the intrinsic interaction energy (ΔEint) between two fragments into four energy components, as follows

| 1 |

where the electrostatic ΔEelstat term originates from the quasi-classical electrostatic interaction between the unperturbed charge distributions of the prepared fragments; the Pauli repulsion ΔEPauli is the energy change associated with the transformation from the superposition of the unperturbed electron densities of the isolated fragments to the wavefunction, which properly obeys the Pauli principle through explicit antisymmetrization and renormalization of the production of the wavefunction. Dispersion interaction, ΔEdisp, is also obtained since we included empirical dispersion with D3(BJ). The orbital term ΔEorb comes from the mixing of orbitals, charge transfer, and polarization between the isolated fragments. This can be further divided into contributions from each irreducible representation of the point group of an interacting system, as follows

| 2 |

The combined EDA–NOCV method is able to partition the total orbital interactions into pairwise contributions of the orbital interactions, which are important in providing a complete picture of the bonding. The charge deformation Δρk(r), which comes from the mixing of the orbital pairs ψk(r) and ψ–k(r) of the interacting fragments, gives the magnitude and the shape of the charge flow due to the orbital interactions (eq 3), and the associated orbital energy ΔEorb presents the amount of orbital energy coming from such interactions (eq 4).

| 3 |

| 4 |

Readers are further referred to the recent review articles to know more about the EDA–NOCV method and its application.56−60 However, the EDA–NOCV analysis of paramagnetic species is quite challenging.35,37 N2 has been considered in singlet and ligand vanadium in different spin states for our EDA–NOCV fragmentations and analyses (see Table S1 in the SI). The charge flow has been shown by deformation densities, red → blue.56

Acknowledgments

S.M. thanks CSIR for SRF. K.C.M thanks SERB for the ECR grant (ECR/2016/000890) and IIT Madras for the seed grant. The authors dedicate this work to Prof. Dr. K. Mangala Sunder on the occasion of his 65th Birthday.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c04472.

EDA–NOCV results at the BP86-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level of V–N2 bonds, optimized coordinates for complexes 1–4 at the BP86 level of theory, QTAIM, and optimized coordinates (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hoffman B. M.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C. Climbing Nitrogenase: Toward a Mechanism of Enzymatic Nitrogen Fixation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 609. 10.1021/ar8002128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossland J. L.; Tyler D. R. Iron–dinitrogen coordination chemistry: Dinitrogen activation and reactivity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 1883. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A. K.; McShea H.; Kolaczkowski B.; Kaçar B. Reconstructing the evolutionary history of nitrogenases: Evidence for ancestral molybdenum-cofactor utilization. Geobiology 2020, 18, 394. 10.1111/gbi.12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Burns R. C.; Fuchsman W. H.; Hardy F. W. F. Nitrogenase from vanadium-grown Azobacter, isolation; characterization; and mechanistic implications. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1971, 42, 353–358. 10.1016/0006-291X(71)90377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sippel D.; Einsle O. The structure of vanadium nitrogenase reveals an unusual bridging ligand. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 956–960. 10.1038/nchembio.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai R.; Minteer S. D. Nitrogenase Bioelectrocatalysis: From Understanding Electron-Transfer Mechanisms to Energy Applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 2736. 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spatzal T.; Schlesier J.; Burger E. M.; et al. Nitrogenase FeMoco investigated by spatially resolved anomalous dispersion refinement. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10902 10.1038/ncomms10902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsson R.; Neese F.; DeBeer S. Revisiting the Mössbauer Isomer Shifts of the FeMoco Cluster of Nitrogenase and the Cofactor Charge. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 1470. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishibayashi Y.Transition Metal-Dinitrogen Complexes Preparation and Reactivity; Nishibayashi Y., Ed.; Wily-VCH verlag GmbH & Co: kGaA, Boschstr, 2019; Vol. 12, p 69469, Print ISBN: 978-3-527-34425-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine P. P.; Yonke B. L.; Zavalij P. Y.; Sita L. R. Dinitrogen complexation and extent of N≡N activation within the group 6 “end-on-bridged” dinuclear complexes; {(η5-C5Me5)M[N(i-Pr)C(Me)N(i-Pr)]}2(μ-η1,η1-N2) (M = Mo; W). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12273–12285. 10.1021/ja100469f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman L. M.; Farrell W. S.; Zavalij P. Y.; Sita L. R. Steric switching from photochemical to thermal reaction pathways for enhanced efficiency in metal-mediated nitrogen fixation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14856–14859. 10.1021/jacs.6b09789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmangles N.; Jenkins H.; Ruppa K. B.; Gambarotta S. Preparation and characterization of a vanadium(III) dinitrogen complex supported by a tripodal anionic amide ligand. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1996, 250, 1–4. 10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05323-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buijink J.-K. F.; Meetsma A.; Teuben J. H. Electron-deficient vanadium alkyl complexes, synthesis and molecular structure of the vanadium(III) dinitrogen complex [(Me3CCH2)3V]2(μ-N2). Organometallics 1993, 12, 2004–2005. 10.1021/om00030a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.-I.; Berno P.; Gambarotta S. Dinitrogen fixation; ligand dehydrogenation; and cyclometalation in the chemistry of vanadium(III) amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 6927–6928. 10.1021/ja00094a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Liang X.; Meetsma A.; Hessen B. Synthesis and structure of an aminoethyl-functionalized cyclopentadienyl vanadium(I) dinitrogen complex. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 7891–7893. 10.1039/c0dt00499e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edema J. J. H.; Meetsma A.; Gambarotta S. Divalent vanadium and dinitrogen fixation, the preparation and X-ray structure of (μ-N2){[(o-Me2NCH2)C6H4]2V(Py)}2(THF)2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 6878–6880. 10.1021/ja00199a079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edema J. J. H.; Stauthamer W.; van Bolhuis F.; et al. Novel vanadium(II) amine complexes, a facile entry in the chemistry of divalent vanadium. Synthesis and characterization of mononuclear L4VCl2 [L = amine; pyridine], X-ray structures of trans-(TMEDA)2VCl2 [TMEDA=N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine] and trans-Mz2V(py)2 [Mz = o-C6H4CH2N(CH3)2; py=pyridine]. Inorg. Chem. 1990, 29, 1302–1306. 10.1021/ic00332a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ferguson R.; Solari E.; Floriani C.; et al. Fixation and reduction of dinitrogen by vanadium(II) and vanadium(III), synthesis and structure of mesityl(dinitrogen)vanadium complexes. Angew. Chem. 1993, 105, 453–455. 10.1002/ange.19931050331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, 396 - 397.

- Berno P.; Hao S.; Minhas R.; Gambarotta S. Dinitrogen fixation versus metal–metal bond formation in the chemistry of vanadium(II) amidinates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 7417–7418. 10.1021/ja00095a059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vidyaratne I.; Gambarotta S.; Korobkov I.; Budzelaar P. H. M. Dinitrogen partial reduction by formally zero- and divalent vanadium complexes supported by the bis-iminopyridine system. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 1187–1189. 10.1021/ic048358+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidyaratne I.; Crewdson P.; Lefebvre E.; Gambarotta S. Dinitrogen coordination and cleavage promoted by a vanadium complex of a σ, π, σ-donor ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 8836–8842. 10.1021/ic701219h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson R.; Solari E.; Floriani C.; et al. Stepwise reduction of dinitrogen occurring on a divanadium model compound, a synthetic, structural, magnetic, electrochemical, and theoretical investigation on the [V=N=N=V]n+ [n=4–6] based complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 10104–10115. 10.1021/ja971229q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groysman S.; Villagrán D.; Freedman D. E.; Nocera D. G. Dinitrogen binding at vanadium in a tris(alkoxide) ligand environment. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10242–10244. 10.1039/c1cc13645c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran B. L.; Pinter B.; Nichols A. J.; et al. A planar three-coordinate vanadium(II) complex and the study of terminal vanadium nitrides from N2, a kinetic or thermodynamic impediment to N–N bond cleavage?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13035–13045. 10.1021/ja303360v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Milsmann C.; Turner Z. R.; Semproni S. P.; Chirik P. J. Azo N=N bond cleavage with a redox-active vanadium compound involving metal–ligand cooperativity. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 5482–5486. 10.1002/ange.201201085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5386 - 5390. [DOI] [PubMed]

- a Kilgore U. J.; Sengelaub C. A.; Pink M.; et al. A transient VIII–alkylidene complex, oxidation chemistry including the activation of N2 to afford a highly porous honeycomb-like framework. Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 3829–3832. 10.1002/ange.200705931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3769 - 3772. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rehder D.; Woitha C.; Priebsch W.; Gailus H. trans-[Na(thf)][V(N2)2(Ph2PCH2CH2PPh2)2], structural characterization of a dinitrogenvanadium complex; a functional model for vadadiumnitrogenase. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992, 28, 364–365. 10.1039/c39920000364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gailus H.; Woitha C.; Rehder D. Dinitrogenvanadates(−I), synthesis; reaction and conditions for their stability. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1994, 23, 3471–3477. 10.1039/DT9940003471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe N. C.; Schrock R. R.; Müller P.; Weare W. W. Synthesis of [(HIPTN=CH2CH2)3N]V compounds (HIPT=3,5-(2,4,6-i-Pr3C6H2)2C6H3) and an evaluation of vanadium for the reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 9197–9205. 10.1021/ic061554r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi Y.; Arashiba K.; Tanaka H.; Eizawa A.; Nakajima K.; Yoshizawa K.; Nishibayashi Y. Catalytic Reduction of Molecular Dinitrogen to Ammonia and Hydrazine Using Vanadium Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 9064. 10.1002/anie.201802310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson B. D.; Peters J. C. Fe-Mediated HER vs N2RR: Exploring Factors That Contribute to Selectivity in P3EFe(N2) (E = B, Si, C) Catalyst Model Systems. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 1448. 10.1021/acscatal.7b03068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.; Sloane F. T.; Blondin G.; Abboud K. A.; García-Serres R.; Murray L. J. Dinitrogen Activation upon Reduction of a Triiron(II) Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1499. 10.1002/anie.201409676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Čorić I.; Holland P. L. Insight into the Iron–Molybdenum Cofactor of Nitrogenase from Synthetic Iron Complexes with Sulfur, Carbon, and Hydride Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7200. 10.1021/jacs.6b00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe L. A.; Ogawa T.; Schrock R. R.; Müller P. Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia Catalyzed by Molybdenum Diamido Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9132. 10.1021/jacs.7b04800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo J. Jr.; Peters J. C. Catalytic Nitrogen-to-Ammonia Conversion by Osmium and Ruthenium Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 16105. 10.1021/jacs.7b10204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Devi K.; Gorantla S. M. N. V. T.; Mondal K. C. EDA-NOCV analysis of carbene-borylene bonded dinitrogen complexes for deeper bonding insight: A fair comparison with a metal-dinitrogen system. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43, 757. 10.1002/jcc.26832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gorantla S. M. N. V. T.; Mondal K. C. Estimations of Fe0/-1–N2 Interaction Energies of Iron(0)-Dicarbene and its Reduced Analogue by EDA-NOCV Analyses: Crucial Steps in Dinitrogen Activation Under Mild Condition. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 3465–3475. 10.1039/D1RA08348A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett C. H.; Agapie T. Activation of an Open Shell, Carbyne-Bridged Diiron Complex Toward Binding of Dinitrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10059. 10.1021/jacs.0c01896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Devi K.; Gorantla S. M. N. V. T.; Mondal K. C. Dinitrogen Binding Relevant to FeMoco of Nitrogenase: Clear Visualization of σ-Donation and π-Backdonation from Deformation Electron Densities around Carbon/Silicon-Iron Site. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202100931 10.1002/ejic.202100931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Foroutan-Nejad C.; Shahbazian S.; Rashidi-Ranjbar P. The critical re-evaluation of the aromatic/antiaromatic nature of Ti3(CO)3: a missed opportunity?. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 4576. 10.1039/c0cp01519a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behaviour. Phys. Rev. A. 1988, 38, 3098. 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P. Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B. 1986, 33, 8822. 10.1103/PhysRevB.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Ehrlich S.; Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456. 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057. 10.1039/b515623h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.et al. Gaussian 16, revision A.03; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Glendening E. D.; Landis C. R.; Weinhold F. NBO 6.0: Natural bond orbital analysis program. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 1429. 10.1002/jcc.23266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis C. R.; Weinhold F.. The NBO View of Chemical Bonding. In The Chemical Bond: Fundamental Aspects of Chemical Bonding; Frenking G.; Shaik S., Eds.; Wiley, 2014; pp 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Weinhold F.; Landis C.R.. Valency and Bonding, A Natural Bond Orbital Donor–Acceptor Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wiberg K. B. Application of the pople-santry-segal CNDO method to the cyclopropylcarbinyl and cyclobutyl cation and to bicyclobutane. Tetrahedron 1968, 24, 1083. 10.1016/0040-4020(68)88057-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler T.; Rauk A. On the calculation of bonding energies by the Hartree Fock Slater method. Theor. Chim. Acta 1977, 46, 1–10. 10.1007/BF02401406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoraj M.; Michalak A. Donor–Acceptor Properties of Ligands from the Natural Orbitals for Chemical Valence. Organometallics 2007, 26, 6576. 10.1021/om700754n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Mitoraj M.; Michalak A. Applications of natural orbitals for chemical valence in a description of bonding in conjugated molecules. J. Mol. Model. 2008, 14, 681. 10.1007/s00894-008-0276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mitoraj M. P.; Michalak A.; Ziegler T. A Combined Charge and Energy Decomposition Scheme for Bond Analysis. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 962. 10.1021/ct800503d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E.; Baerends E. J. Optimized Slater-type basis sets for the elements 1–118. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1142. 10.1002/jcc.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenthe E. v.; Baerends E. J.; Snijders J. G. Relativistic regular two-component Hamiltonians. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 4597. 10.1063/1.466059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E.; Baerends E. J.; Snijders J. G. Relativistic total energy using regular approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101, 9783. 10.1063/1.467943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ADF2017, SCM, Theoretical Chemistry; Vrije Universiteit: Amsterdam, The Netherlands: http://www.scm.com.

- Zhao L.; Pan S.; Holzmann N.; Schwerdtfeger P.; Frenking G. Chemical Bonding and Bonding Models of Main-Group Compounds. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8781. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.; Hermann M.; Schwarz W. H. E.; Frenking G. The Lewis electron-pair bonding model: modern energy decomposition analysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2019, 3, 48. 10.1038/s41570-018-0060-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorantla S. M. N. V. T.; Pan S.; Mondal K. C.; Frenking G. Stabilization of Linear C3 by Two Donor Ligands: A Theoretical Study of L-C3-L (L=PPh3, NHCMe, cAACMe). Chem. - Eur. J. 2020, 26, 14211. 10.1002/chem.202003064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorantla S. M. N. V. T.; Pan S.; Mondal K. C.; Frenking G. Revisiting the Bonding Scenario of Two Donor Ligand Stabilized C2 Species. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 291. 10.1021/acs.jpca.0c09951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorantla S. M. N. V. T.; Mondal K. C. Energy Decomposition Analysis Coupled with Natural Orbitals for Chemical Valence and Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shift Analysis of Bonding, Stability, and Aromaticity of Functionalized Fulvenes: A Bonding Insight. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 17798–17810. 10.1021/acsomega.1c00648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.