Abstract

Vibrio parahaemolyticus has dual flagellar systems adapted for locomotion under different circumstances. A single, sheathed polar flagellum propels the swimmer cell in liquid environments. Numerous unsheathed lateral flagella move the swarmer cell over surfaces. The polar flagellum is produced continuously, whereas the synthesis of lateral flagella is induced under conditions that impede the function of the polar flagellum, e.g., in viscous environments or on surfaces. Thus, the organism possesses two large gene networks that orchestrate polar and lateral flagellar gene expression and assembly. In addition, the polar flagellum functions as a mechanosensor controlling lateral gene expression. In order to gain insight into the genetic circuitry controlling motility and surface sensing, we have sought to define the polar flagellar gene system. The hierarchy of regulation appears to be different from the polar system of Caulobacter crescentus or the peritrichous system of enteric bacteria but is pertinent to many Vibrio and Pseudomonas species. The gene identity and organization of 60 potential flagellar and chemotaxis genes are described. Conserved sequences are defined for two classes of polar flagellar promoters. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of mutant strains with defects in swimming motility coupled with primer extension analysis of flagellar and chemotaxis transcription provides insight into the polar flagellar organelle, its assembly, and regulation of gene expression.

Many bacterial species are motile by means of flagellar propulsion (reviewed in references 5, 32, and 33). Powered by a rotary motor, the flagellum acts as semirigid helical propeller, which is attached via a flexible coupling, known as the hook, to the basal body. The basal body consists of rings and rods that penetrate the membrane and peptidoglycan layers. Associating with the basal body and projecting into the cytoplasm is a structure termed the C ring, which contains the switch proteins and acts as the core, or rotating part, of the motor. Maintenance of a flagellar motility system is a sizable investment with respect to cellular economy in terms of the number of genes and the energy that must be committed to gene expression, protein synthesis, and flagellar rotation. As a result, flagellar systems are highly regulated. A hierarchy of regulation has been elucidated for peritrichously flagellated Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (26, 27, 30). This scheme of control couples gene expression to assembly of the organelle. The pyramid of expression possesses three classes, or tiers, of genes. Genes in each class must be functional in order for expression of the subsequent class to occur. Class 1 genes, flhD and flhC, encode the master transcriptional activators of class 2 flagellar gene expression. The flhDC operon is controlled by a ς70 promoter and a number of global regulatory factors (28). The majority of the class 2 flagellar genes encode components of the flagellar export system and the basal body (21). One class 2 gene encodes an alternative sigma factor devoted to recognition of flagellar genes (44). Flagellar class 3 operons are positively controlled by the flagellar ς28 factor and negatively regulated by FlgM, an anti-sigma factor (45). The anti-sigma factor is retained within the cell until the flagellar basal body and hook are completed (18, 29). At that time, FlgM is exported, and ς28 becomes free to direct expression of class 3 genes encoding flagellin subunits, hook-associated, motor, and chemotaxis signal transduction proteins. There are additional intricacies to this cascade, e.g., transcriptional classes within classes and translational modulation coupled to basal body assembly, as well as linkage between cell division and flagellar production (1, 22, 31, 48, 49). The regulatory hierarchy established for E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium serves as the paradigm for peritrichous flagellar systems of other bacteria.

The other well-characterized set of flagellar genes and scheme of flagellar control are those of Caulobacter crescentus (reviewed in references 46 and 65). In this organism, flagellation and cell division are strikingly coupled. On cell division, the daughter cell is motile and propelled by a polar flagellum, while the mother cell is nonmotile and stalked. DNA replication is repressed in the motile cell until later in the cell cycle when that cell differentiates to a new stalked cell. Many of the genes required for flagellar biosynthesis are homologs of E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium genes; however, the flagellar hierarchy differs between C. crescentus and the enteric bacteria. The flagellar genes of C. crescentus are organized in four levels of expression with two assembly checkpoints: completion of the MS-ring-switch export complex and completion of the basal body-hook structures. Genes at the bottom of the hierarchy are transcriptionally regulated from ς54 promoters. The master transcriptional regulator at the top of the hierarchy is CtrA, a member of the response regulator family of two component signal transduction systems, and this regulator controls the initiation of DNA replication, DNA methylation, cell division, and flagellar biogenesis (11).

The flagella of V. parahaemolyticus are of particular interest because this organism possesses two flagellar systems: a peritrichous (or lateral) one that is expressed when the bacterium is on a surface or in viscous environments and a polar system that is expressed continuously, i.e., when the bacterium is grown in liquid or on surfaces (reviewed in reference 39). Thus, under some conditions the bacterium simultaneously assembles two distinct flagellar organelles. Prior genetic analysis suggests that the gene systems are distinct and that no structural or assembly components are shared; mutants isolated with defects in swarming translocation are competent for swimming motility in liquid, and swimming-defective mutants remain proficient for swarming. Energy for rotation of the two kinds of flagella derives from different sources. The sodium motive force powers rotation of the polar flagellum, and the proton motive force drives rotation of the lateral flagella. Some of the chemotaxis genes have been demonstrated to be shared by the two motility systems (53). In addition to its propulsive role in swimming, the polar flagellum is believed to act as a tactile sensor informing the bacterium of contact with surfaces. Conditions that inhibit rotation of the polar organelle induce the alternative, lateral motility system. In this work, we elucidate the genes and gene organization involved in the polar motility system. Until now the circuitry of a polar flagellar system, apart from C. crescentus, has not been traced. This work should provide a foundation for gaining insight into the flagellar organelle and regulation of flagellar gene expression for a number of polarly flagellated bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Vibrio cholerae, and other marine Vibrio species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

V. parahaemolyticus strains were cultured at 30°C. The strains used in this work are derivatives of V. parahaemolyticus BB22 (4). Strain LM1017 contains a mutation in the lateral flagellar hook gene and is unable to swarm (42). Strains were routinely propagated in heart infusion (HI) broth, which contained 25 g of HI broth (Difco) and 20 g of NaCl per liter. Marine broth 2216 (Difco) (28 g per liter) was filtered after autoclaving to remove precipitate. Solidified swarming medium was prepared by adding 15 g of Bacto-Agar (Difco) per liter to HI broth. Semisolid motility medium (M agar) contained 10 g of tryptone, 20 g of NaCl, and 3.25 g of agar per liter.

Genetic and molecular techniques.

General DNA manipulations were adapted from the methods of Sambrook et al. (52). Transposon mutagenesis with mini-Mu lac (Tetr) and the strategy for cloning the targeted gene have been described previously (58). The V. parahaemolyticus cosmid library was prepared by using the pLAFRII vector (40). Chromosomal DNA was prepared according to the protocol of Woo et al. (64). Southern blot analysis of restricted genomic DNA (52) was performed on Hybond-NX nylon membranes (Amersham Life Science).

Motility assays.

The effect of mutations on swimming motility was assessed by examining movement in M agar. To document swimming motility, plates were inoculated with 2 μl of an overnight culture of cells normalized to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 2.0. Plates were incubated and photographed using a Kodak Digital Imaging System.

Immunoblot analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was conducted as described previously (40). Resolving gels contained 12% acrylamide. Gels were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore Corp.) in buffer containing 12.5 mM Tris base, 96 mM Glycine, and 20% methanol for 90 min at 30 V. After blocking in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8], 0.15 M NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) containing 5% nonfat dry milk, blots were incubated in TBST buffer with antiflagellar antibodies. The production of antibodies to polar and lateral flagellins has been described previously (34, 42). The secondary antibody was anti-rabbit immunoglobulin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Life Sciences). It was incubated with the blot at a dilution of 1:20,000 in TBST for 1 h. Development of the immunoblot utilized the chemiluminescent Super Signal substrate (Pierce) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Primer extension analysis.

RNA was prepared with Trizol reagent (Gibco-BRL/Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Broth-grown cells were harvested in late exponential phase (OD600 = 1.0). Plate-grown cells were harvested in cold 0.3 M sucrose after 5 to 7 h of growth. Primer extension analysis was performed as described previously (38) by use of the avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

Sequence analysis.

Sequence determination on both strands was performed by the DNA Core Facility of the University of Iowa. Sequence assembly and detection of potential rho-independent transcriptional terminators were accomplished by using the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) software package. Searches for homology were performed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the BLAST network service (2). Multiple sequence alignments were performed by using the CLUSTAL W program (62).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences have been deposited in GenBank, and the accession numbers are U12817, AF069392, AF069391, U09005, and U06949.

RESULTS

Transposon mutagenesis and isolation of strains with swimming motility defects.

After mini-Mu lac (Tetr) mutagenesis of strain LM1017, a transposon bank containing approximately 15,000 mutants was screened for mutants with defects in the polar motility system. Strain LM1017 contains a lux operon fusion to the lateral flagellar hook gene; therefore, there is no contribution from the lateral flagellar system to the motility of this strain (42). Strain LM1017 expresses the lfgE::lux fusion when grown on solidified medium and is luminescent. All of the mutants with swimming motility defects produced as much light on plates as the parental strain LM1017 produced, were unable to swarm over surfaces, and failed to synthesize lateral flagellin. Strains that appeared nonmotile or poorly motile in semisolid motility (M) agar potentially possessed defects in polar flagellar structure or assembly, motor function, or chemotaxis.

Phenotypic analysis of mutants.

The majority of nonmotile mutants of E. coli are nonflagellated (Fla−) due to the nature of feedback control built into the hierarchy of gene expression (66). Loss-of-function mutations in only two genes (motA and motB) yield the Mot phenotype, which is a flagellated but paralyzed cell. Insertion of the torque-generating components of the motor into the membrane is not required for assembly of the E. coli flagellar organelle, and expression of mot genes occurs at the final stage in the hierarchy of expression (57). The phenotypes of V. parahaemolyticus motility mutants differed from E. coli. Forty mutants were segregated into four phenotypic classes: class 1, Fla− mutants were nonmotile in semisolid M agar and in the light microscope and failed to produce flagellin in immunoblots (26%); class 2, Mot− mutants were nonmotile in M agar and in the microscope but produced flagellin antigen levels equivalent to the wild-type strain (1%); class 3, Che− mutants appeared nonmotile in M agar but motile in the light microscope and produced wild-type levels of flagellin (39%); and class 4, Mot± mutants showed limited radial expansion in M agar after prolonged incubation and produced detectable, but low levels of Fla antigen (34%).

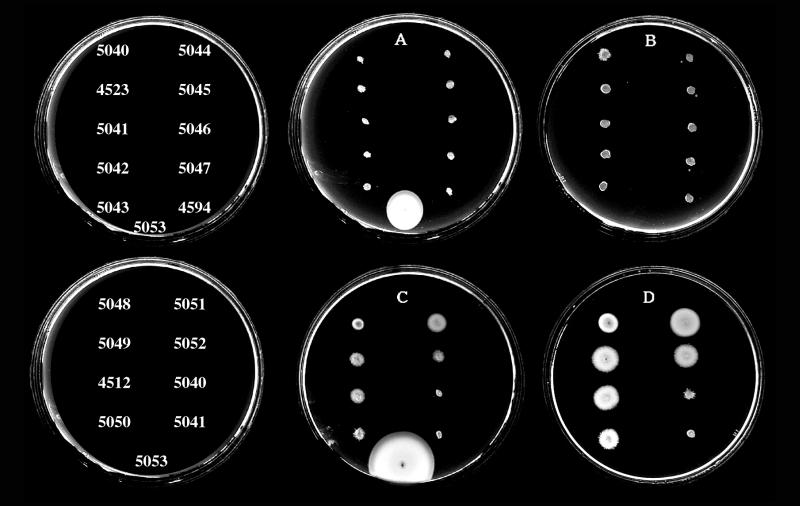

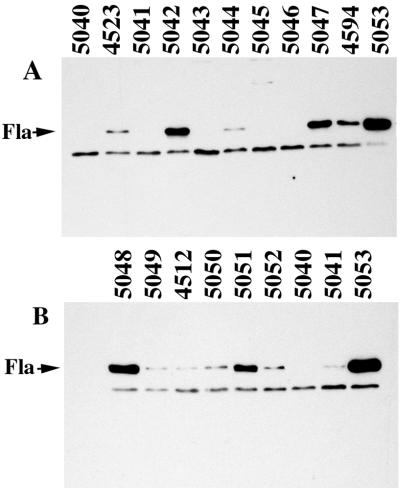

The fourth class was the unexpected class. Further analysis of a subset of mutants from this class and representative mutants of the Fla− class was pursued. Two phenotypic classes of selected motility mutants were observed in M agar: (i) completely nonmotile strains with defects that resulted in no translocation (Fig. 1, plates A and B, incubated for 10 and 24 h, respectively) and (ii) strains with lesions that allowed slight translocation after extended incubation times (Fig. 1, plates C and D, incubated for 12 and 24 h, respectively). The partial motility of Mot± mutants in M agar was not the result of reversion or suppression giving rise to motile cells because the phenotype was stable. Observation of the poorly motile strains in the light microscope revealed a small percentage (≤0.05 to 0.5%) of motile cells in each population. Motility appeared to be the result of polar flagellar propulsion because all of the mutants retained the lfg::lux reporter, were unable to swarm, and failed to produce lateral flagellin. The polar flagellin profiles that are displayed in the immunoblots (see Fig. 2) correspond to the mutants in the nonmotile and the slightly motile sets shown in Fig. 1. The mutants were observed to synthesize various levels of flagellin antigen. The correlation of motility phenotype with flagellin antigen production is shown in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Swimming motility of mini-Mu mutant strains in M agar with tetracycline. All strains were derivatives of strain LM1017. Plates A and B contain the strains indicated in the top row at the left and were incubated at 30°C for 10 and 24 h, respectively. Plates C and D contain the strains indicated in the lower row on the left and were incubated at 30°C for 12 and 24 h, respectively. Strain LM5053 was not inoculated in plates B or D. The control strain LM5053 was tetracycline-resistant and exhibited wild-type motility.

FIG. 2.

Western immunoblot analysis of polar flagellin production. Blots were reacted for 2 h with antiserum (1:1,000 dilution) directed against polar flagellins (Fla). The strain numbers are indicated above the lanes. The polar flagellins are similar in molecular size and comigrate in the resolving gel system used. An antiserum-reactive, nonflagellin band serves as a control for the amount of whole cells loaded in each lane.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypes of mini-Mu insertion mutant strains

| Strain namea | Mot phenotypeb | Fla phenotypec | Polar gene defect intervald |

|---|---|---|---|

| LM4512 | Mot± | Fla± | flgFGH |

| LM4523 | Mot− | Fla± | flgFGH |

| LM4594 | Mot− | Fla± | flgDE |

| LM5040 | Mot− | Fla− | flhBA |

| LM5041 | Mot− | Fla± | flgDE |

| LM5042 | Mot− | Fla+ | flgKL |

| LM5043 | Mot− | Fla− | flhA |

| LM5044 | Mot− | Fla± | flgHIJK |

| LM5045 | Mot− | Fla− | flhBA |

| LM5046 | Mot− | Fla− | flhBA |

| LM5047 | Mot− | Fla± | flgBC |

| LM5048 | Che− | Fla+ | cheB |

| LM5049 | Mot± | Fla± | flgFGH |

| LM5050 | Mot± | Fla± | flgBC |

| LM5051 | Mot± | Fla+ | flhAF |

| LM5052 | Mot± | Fla± | flgFGH |

| LM5053e | Mot+ | Fla+ | None |

All strains were derived from strain LM1017, which is defective for swarming motility as a result of a mutation in the lateral flagellar hook gene (lfgE313::lux).

Mot−, nonmotile in M agar and in light microscope; Mot±, slight radial expansion in M agar and a low population of motile cells in light microscope; Che−, slight radial expansion in M agar and highly motile population in light microscope.

Fla+, polar flagellar antigen levels in immunoblots equivalent to wild type; Fla−, no Fla antigen; Fla±, intermediate levels of Fla antigen.

Mutations created by mini-Mu insertion were mapped by Southern analysis to specific restriction fragments carrying indicated genes.

Wild-type phenotype for motility with random mini-Mu insertion.

Identification of polar flagellar genes: physical organization and predicted function.

The tetracycline resistance from mini-Mu and flanking chromosomal DNA was cloned from some of the mutants of each class and used as a probe to retrieve cosmids from a library of V. parahaemolyticus DNA. Each cosmid contained inserts of approximately 25 kb of DNA. Cosmids were used as probes for Southern blots containing restricted chromosomal DNA of the mutant strains. The cosmids revealed perturbations of the restriction pattern due to transposon insertion and allowed segregation of the mutants into linkage groups. DNA from mutants failing to show perturbations on Southern analysis was used to prepare subsequent substrates for cloning to retrieve additional loci. The initial sequence was obtained from the Mu-derived, tetracycline-resistant clones, and the nucleotide information obtained was used to continue sequencing on both strands of the cosmid clones.

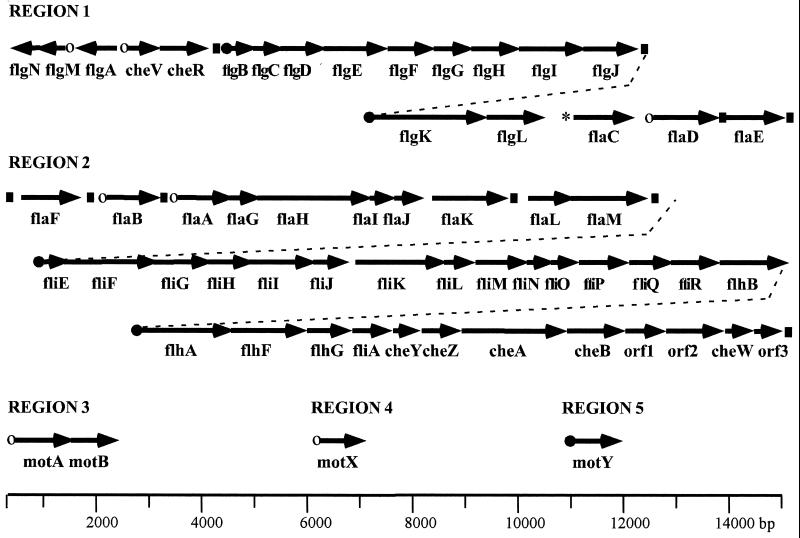

Figure 3 presents a diagram of the loci obtained and the organization of the flagellar and chemotaxis genes identified. Fifty-seven potential genes encode products which are homologous to flagellar and chemotaxis proteins of other bacterial flagellar systems. In addition, there were three open reading frames (ORFs) that coded for proteins with little resemblance to flagellar sequences in the databases. The majority of the genes occurs in two regions and may be organized in large operons. Intergenic regions of less than 60 bp separate many ORFs, and some appear to be translationally coupled. The sequences contain few transcriptional termination signals (indicated by boxes in Fig. 3). The closest homologs to many of the genes are found in V. cholerae, P. aeruginosa, and Pseudomonas putida species. For similar genes that have been sequenced in these bacteria, the gene organization also seems highly conserved between organisms.

FIG. 3.

Organization of polar flagellar gene system. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription and the extent of coding sequence for each gene. The filled circles indicate the ς54 class, and the open circles indicate the ς28 class of promoters that have been mapped by primer extension analysis. The promoter region for flaC is unusual and is indicated by the asterisk. The filled boxes indicate predicted rho-independent transcriptional terminators.

The polar flagellar system (Fla) is the default motility system and is produced continuously; therefore, most of the polar flagellar genes have been named analogously to homologs in other bacteria (20). Genes in the lateral flagellar system (Laf) are expressed under particular conditions and have been assigned designations that are permutations of the fla nomenclature. Table 2 summarizes the homology and predicted function of the gene products. By comparison with E. coli, a full complement of genes encoding flagellar structural components and the export apparatus has probably been elucidated; there are a few omissions and a few additions. The ORF directly downstream of flgM (region 1) encodes a polypeptide 141 amino acids (aa). Although it shows no homology to known flagellar gene products, we predict it may be functionally equivalent to FlgN, which is reported to act as a chaperone required for filament assembly (14), due to its size and location. Similarly, the fliT gene equivalent is missing, although there are two ORFs in region 2 (flaG and flaI) that encode proteins of similar size to E. coli FliT, which is also reported to play a chaperone-like role (14, 67). No homologs to the products of the flagellar master regulatory genes flhD and flhC exist, although alternate, potential regulatory genes, i.e., flaK, flaL, and flaM, occur in region 2. The predicted gene products, which resemble a number of two-component response regulators, show highest similarity to flagellar regulatory proteins of P. aeruginosa and V. cholerae (3, 25, 50). There are additional genes present in V. parahaemolyticus that are found in flagellar operons of other nonenteric bacteria, in particular flhF and flhG, which resemble GTP- and ATP-binding proteins, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Chemotaxis and polar flagellar genes of V. parahaemolyticus

| Region (GenBank no.) and gene | Gene product homolog or predicted function | Region (GenBank no.) and gene | Gene product homolog or predicted function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (U12817) | 2 (AF069392) | |||

| flgN | None; potential chaperone | flaF | Flagellin | |

| flgM | Anti-ς28 factor | flaB | Flagellin | |

| flgA | Necessary for P-ring addition | flaA | Flagellin | |

| cheV | Chemotaxis CheY/CheW hybrid | flaG | Slight homology to N terminus of multiple flagellins | |

| cheR | Chemotaxis methyltransferase | flaH | HAP2 | |

| flgB | Rod | flaI | None | |

| flgC | Rod | flaJ | FliS | |

| flgD | Rod | flaK | Two-component response regulator | |

| flgE | Hook | flaL | Two-component sensor kinase | |

| flgF | Rod | flaM | Two-component response regulator | |

| flgG | Rod | |||

| flgH | L ring | fliE | Hook-basal body component | |

| flgI | P ring | fliF | M ring | |

| flgJ | Peptidoglycan hydrolyzing flagellar protein | fliG | Switch component | |

| flgK | HAP1 | fliH | Fla export and assembly | |

| flgL | HAP3 | fliI | Fla export; ATP synthase | |

| flaC | Flagellin | fliJ | Fla export and assembly | |

| flaD | Flagellin | fliK | Hook length control | |

| flaE | Flagellin | fliL | Flagellar protein | |

| fliM | Switch component | |||

| fliN | Switch component | |||

| 3 (AF069391) | fliO | Fla export and assembly | ||

| motA | Na+ motor component | fliP | Fla export and assembly | |

| motB | Na+ motor component | fliQ | Fla export and assembly | |

| fliR | Fla export and assembly | |||

| flhB | Fla export and assembly | |||

| flhA | Fla export and assembly | |||

| flhF | Flagellar protein; also homologous to FtsY; potential GTP-binding protein | |||

| 4 (U09005), motX | Na+ motor component | flhG | MinD and other ATP-binding proteins | |

| fliA | RNA polymerase ς28 factor | |||

| 5 (U06949), motY | Na+ motor component | cheY | Causes change in direction of flagellar rotation | |

| cheZ | Dephosphorylates CheY | |||

| cheA | CheA kinase | |||

| cheB | Chemotaxis methylesterase | |||

| ORF1 | Soj-like and other chromosome-partitioning ATPase proteins | |||

| ORF2 | Unknown | |||

| cheW | Purine-binding chemotaxis protein | |||

| ORF3 | Unknown |

The complement of che genes and their organization are different from E. coli. Genes encoding the methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins have not been found within the flagellum-chemotaxis clusters. Novel genes include cheV (in region 1), which encodes a hybrid CheY-CheW protein that also exists in Bacillus subtilis (51) and three unusual ORFs that occur within the che gene cluster of region 2. ORF1 encodes a protein that resembles Soj of B. subtilis and other ATPase proteins involved in chromosome partitioning (55); the other ORFs encode proteins that fail to resemble proteins of known function. Similar coding regions, specifically ORF1 and ORF2, have been observed in a chemotaxis locus of P. putida (10).

Most of the predicted V. parahaemolyticus polar flagellar gene products align with flagellar counterparts in other organisms throughout the length of each protein. Some proteins show divergence at the N terminus. An example is the M ring, which is the fliF product. Alignment begins at aa 62 of V. parahaemolyticus FliF with aa 33 of E. coli FliF. Another case occurs with the product of flgH (259 aa), which potentially encodes the L ring of the flagellar basal body. The first 94 aa of V. parahaemolyticus FlgH fail to align with known FlgH proteins, whereas the remainder of the molecule produces significant alignment with other FlgH proteins, e.g., 39% identities and 57% positives with E. coli FlgH using BLAST analysis. In comparison, the full lengths of V. parahaemolyticus FlgI and E. coli FlgI align completely (46% identities and 65% positives). E. coli FlgI forms the P ring. A few proteins show significant gaps within the alignment. One striking example is FlhF (505 aa), which contains an insertion spanning 170 aa that is not found in other homologs; this domain shows limited homology with the sodium channel I of rat using BLAST analysis (35% identities and 55% positives).

Correlation of genotype with phenotype.

Sequence information coupled with restriction patterns using Southern analysis allowed assignment of lesions to specific gene intervals. The majority of the chemotaxis-defective mutants analyzed showed transposon-induced perturbations that placed the insertion defects within che clusters in region 1 or region 2. A minority (1%) of nonmotile V. parahaemolyticus mutants displayed the Mot− phenotype, and three mutants were determined to contain mutations in novel motor genes, motX and motY (35, 36). A correlation of the genotype of the Fla− and Mot± mutants examined in Fig. 1 and 2 with phenotype is presented in Table 1. Strains LM5040, LM5043, LM5045, and LM5046 produced no flagellin, and the mini-Mu insertions in these strains mapped to intervals within the flhBA locus, which encodes components of the flagellar export pathway. One other insertion in the flhBA locus was detected. The phenotype and genotype of this strain, LM5051, was puzzling until the precise mutation was cloned and sequenced. LM5051 was partially motile and produced levels of flagellin comparable to wild-type levels. Cloning and sequencing of the mini-Mu insertion of this strain revealed that the transposon was inserted into the intergenic region between flhA and flhF. Nonmotile strain LM5042 also produced as much flagellar antigen as the wild type and contained a defect in the region encoding hook-associated-like proteins (the flgKL interval). The phenotype of LM5042 matched other strains with insertions in flgK and flgL that were previously created by allelic exchange (37). All of the mutants in the Mot± class mapped in the flgB-flgH interval, which encodes hook and basal body components. Thus, mutants with defects in genes encoding assembly apparatus fail to produce a flagellum or synthesize flagellins, whereas mutants with defects in many of the genes encoding structural parts of the basal body, but not hook-associated proteins, seem to be able to occasionally synthesize a functional polar flagellum.

Six polar flagellin genes.

Prior work identified genes encoding four polar flagellin subunits that were organized in tandem in two distinct loci, flaBA and flaCD (37). Further sequencing of the flagellin-encoding loci revealed two additional flagellin genes, flaF (located upstream of flaB transcription) and flaE (located downstream of flaD transcription). Thus, the present total number of genes encoding the structural subunits of the polar flagellar filament is six. A comparison of their relatedness to each other and to the lateral flagellin is shown in Table 3. Their location, homology, and genetic analysis suggest that these are polar genes; however, none of the flagellin genes appears to be essential for polar filament formation (37).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the flagellins of V. parahaemolyticus

| Flagellin | % Identitya with other V. parahaemolyticus flagellins

|

Length (aa) | Homologb | % Identity to homologb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FlaA | FlaB | FlaC | FlaD | FlaE | FlaF | ||||

| FlaA | 100 | 78 | 65 | 78 | 48 | 67 | 376 | vcFlaB | 83 |

| FlaB | 100 | 68 | 99 | 50 | 69 | 378 | vaFlaD | 85 | |

| FlaC | 100 | 68 | 45 | 64 | 384 | vcFlaA | 78 | ||

| FlaD | 100 | 50 | 68 | 378 | vaFlaD | 85 | |||

| FlaE | 100 | 47 | 374 | vcFlaD | 49 | ||||

| FlaF | 100 | 377 | vaFlaE | 78 | |||||

| LafAc | 34 | 33 | 35 | 33 | 27 | 34 | 284 | ppFla | 41 |

Percent identities were determined by GCG BestFit analysis.

Closest homolog in another organism identified by using a BLAST search. va, vc, and pp, V. anguillarum, V. cholerae, and P. putida, respectively.

LafA is the lateral flagellin.

In order to gain insight into why this organism possesses such an extraordinary number of flagellins and to begin to elucidate flagellar transcriptional control, primer extension analysis was used to define promoter structure. Previous analysis suggested that the genes occurred in distinct transcriptional units. The flaA, flaB, and flaD genes possessed upstream sequences resembling the consensus ς28-dependent flagellar promoter (TAAA n15 GCCGTTAA [17]), and flagellin production in E. coli was shown to be dependent on the product of E. coli fliA, ς28 (42). In contrast, flaC was very poorly expressed in E. coli, and immunodetection of FlaC flagellin required the product of an additional gene, flaJ, which resembles the putative chaperone FliS (60). In E. coli, flaC expression did not require ς28.

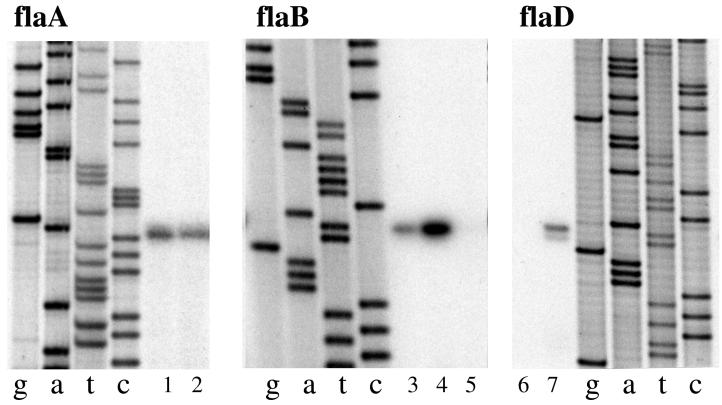

Primer extension analysis in V. parahaemolyticus supports the idea that a polar flagellum-specific ς28 recognizes the promoters of flaA, flaB, and flaD (Fig. 4 and Table 4). Primer extension products using flaA-, flaB-, or flaD-specific primers were identical in reactions using RNA prepared from broth- or plate-grown cells. Upstream of the coding sequence for flagellin F are sequences similar to the promoters of flaA, flaB, and flaD; however, we have been unable to detect a discrete primer extension product. There appears to be some readthrough transcription originating upstream of the flaF gene. Primer extension analysis suggested that flaE is cotranscribed with the flaD coding region, although the intergenic region between the flaD and flaE, which is 122 bp, contains a predicted rho-independent terminator structure. A ladder of products was obtained using reverse transcriptase that had been primed with an oligonucleotide designed to hybridize to the 5′ end of the flaE message. The lengths of the products were calculated to extend into the flaD-coding region (data not shown); therefore, it appears that flaD and flaE may be coexpressed as a single transcriptional unit. Prior genetic evidence supports this hypothesis; no polar flagellin can be detected in a ΔflaFBA ΔflaCD mutant (37).

FIG. 4.

Primer extension analysis of flagellin gene transcription. RNA was prepared from the wild-type strain BB22 after growth in HI broth (B) or on HI plates (P). The amount of RNA in each lane was as follows: 1, 2 μg (B); 2, 2 μg (P); 3, 2 μg (B); 4, 5 μg (P); 5, minus RNA; 6, minus RNA; and 7, 2 μg (B). Lanes g, a, t, and c correspond to the dideoxy nucleotide used in the sequencing reactions. Sequence and primer extension products were generated with flaA-, flaB-, or flaD-specific primers. The primers were flaA (5′-GCTGTGCGGTCATCGCAGAAACG-3′), flaB (5′-GTGTTTAATTCACTGCCATG-3′), and flaD (5′-CGGTCATCGCTGATACGTTAGTG-3′).

TABLE 4.

Flagellar promoter structure

| Gene | Promoter regionsa |

|---|---|

| Potential ς28-dependent promoters | |

| flaA | CTAAAG gatatgcatacgtc GCCGTTAA agggact G |

| flaB | CTAAAG aaatcaggttgagc GCCGTTAA taaaagt A |

| flaD | CTAAAG cttctgaatttggt GTCGTTAA tagaagt AA |

| motX | CTAAAG cttagctgcagatt GCCGATAA gtttatc A |

| motAb | CTAAAA aaatctgttctagtt GTCGATAC aagtaat A |

| cheV | CTAAAc atactgagcaaaat GCCGATAG acttagc G |

| flgMb | tTAAAG ttatcgtttggttg GTCGATAG tctggat A |

| Consensus | CTAAAG n14 G(C/T)CG(A/T)TAA n7 +1 |

| Potential ς54-dependent promoters | |

| motY | TGGC gggattt TTGC atgacaatcgtt G |

| flgB (P1)c | TGGC ttgctta TTGC agtctaaaacgtc A |

| flgB (P2) | TGGC acgctaa TTGC tatttagttatt A |

| flgK | TGGC acatctt TTGC tttcacttgtcta G |

| flhAb | aGGC gaaatgg TcGC gtataaacatt A |

| fliE | TGGC acataaa TTGC tgtgtcaatattt A |

| Consensus | TGGC n7 TTGC n11-13 +1 |

| Other promoters, flaC | tttagcaagtaatttttacggtcagtgcttatccaa A |

Defined by primer extension analysis. Underlined, capitalized nucleotide designates +1 with respect to transcription. Uppercase letters indicate residues conserved among polar flagellar promoters or with respect to consensus promoters.

Faint ladders of primer extension products suggest that the gene may also be transcribed as part of a larger transcriptional unit initiating from the promoter of an upstream gene.

Two primer extension products, labeled P1 and P2, resulted for the flgB promoter. P1 and P2 are separated by 62 bp.

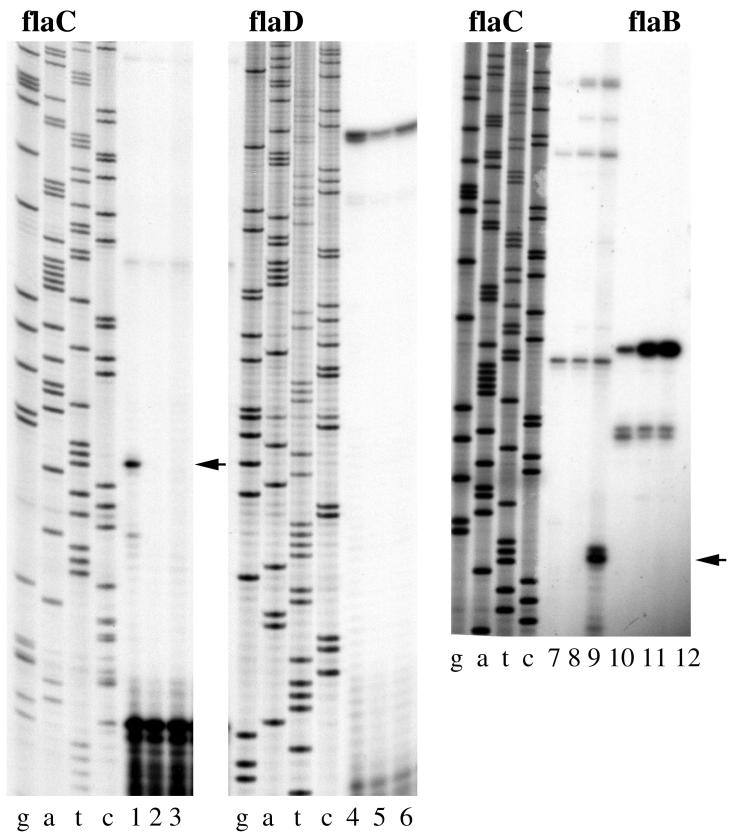

Expression of flaC is unique.

Figure 5 shows the primer extension reactions that were initiated using an oligonucleotide specific for flaC. A major product was obtained (lane 1, indicated by arrow), and the upstream sequences do not resemble the upstream regions of the other ς28-like flagellin promoters (Table 4). Moreover, the product was only observed in RNA prepared from plate-grown wild-type cells and not in RNA from wild-type cells grown in broth (lane 1 versus 2). Expression of flaC appeared to be surface dependent. The control panel, labeled flaD, demonstrates that equivalent amounts of plate- and broth-derived RNA were used. The control reactions used the same RNA preparations and a flaD-specific primer (lanes 1 and 2 compared to 4 and 5, respectively). The flaD transcript was expressed in the wild-type strain in liquid and on surfaces. We have shown previously that plate-grown cells are starved for iron (41). To examine whether the environmental signal controlling flaC expression might be the result of iron starvation or some other nutrient condition, RNA was prepared from the wild-type cells that were grown in 2216 marine broth, which is growth limiting for phosphate and iron (40, 41). No flaC-dependent primer extension product was observed under this condition, although a flaB-dependent transcript could be detected (lane 7 versus lane 10). Primer extension reactions using RNA prepared from HI broth and plate cultures that were cultured in parallel to the 2216 broth culture reproduced the surface-induced flaC product (lanes 8 and 9 versus lanes 11 and 12). There is also a ladder of large primer extension products (most evident in lanes 7 to 9), suggesting some basal level of readthrough transcription originating with the upstream flgK operon.

FIG. 5.

Primer extension analysis of flaC transcription. The arrows indicate the surface-dependent flaC primer extension product. RNA was prepared from the wild-type strain BB22 or LM1017 after growth in HI broth (B), on HI plates (P), or in 2216 marine broth (2216B). Approximately 2 μg of total RNA was used in each primer extension reaction. Reactions 1 to 3 and 7 to 9 were primed with a flaC-specific oligonucleotide. Reactions 4 to 6 were primed with a flaD-specific oligonucleotide. Reactions 10 to 12 were primed with a flaB-specific oligonucleotide. Lanes: 1, BB22 (P); 2, BB22 (B); 3, LM1017 (P); 4, BB22 (P); 5, BB22 (B); 6, LM1017 (P); 7, BB22 (2216B); 8, BB22 (B); 9, BB22 (P); 10, BB22 (2216B); 11, BB22 (B); and 12, BB22 (P). Lanes g, a, t, and c correspond to the dideoxy nucleotide used in the sequencing reactions. Sequence and primer extension products were generated with flaC-, flaD-, or flaB-specific primers. The flaC-specific primer was 5′-CTGTTACAGCCATTTTGCTCTCC-3′.

Prior work established that the mutation in LM1017 occurs in a gene (the hook gene, lfgE) near the top of the lateral flagellar hierarchy and that many surface-dependent genes, including genes coding the lateral-specific flagellar ς28 and lateral flagellin, fail to be expressed in LM1017 (42). No flaC-dependent primer extension product was obtained using RNA prepared from plate-grown LM1017 (lane 3), although flaD-specific product could be detected (lane 3 versus lane 6). Thus, flaC expression appears to require an intact lateral flagellar genetic pathway.

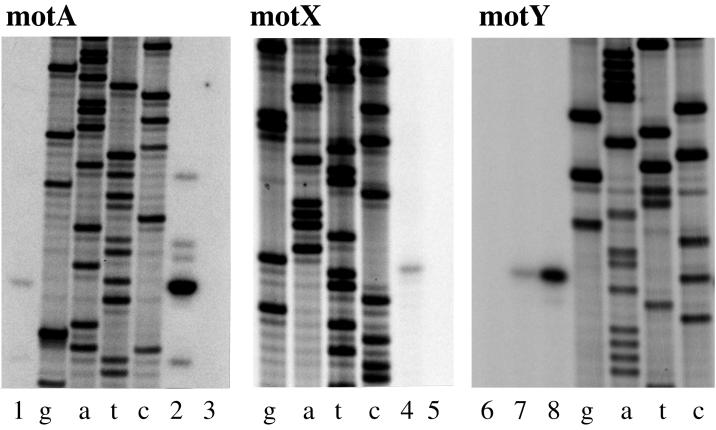

Other flagellar and chemotaxis promoters.

To establish a basis for the polar flagellar regulatory hierarchy, the transcriptional start sites for a number of other promoters were determined. The basic strategy targeted genes that possessed significant upstream, intergenic, or noncoding sequence (usually >50 bp). Figure 6 shows the primer extension products for motA, motX, and motY. Table 4 shows the tabulation of the upstream sequence information for all of the transcriptional start sites that have been determined. Both motA and motX possess upstream sequences that resemble the ς28-dependent promoters, whereas the sequences upstream of motY appear to resemble a potential ς54-dependent promoter (TGGCAC n5 TTGC, containing an invariant −24 GG motif and a conserved −12 GC motif [56]). All mot transcripts were expressed in broth- and plate-grown cells. Table 4 also shows the transcriptional start site and upstream sequences for six other genes. The promoters for cheV and flgM appear to be ς28 dependent, and fliE, flgB, flgK, and flhA appear to be ς54 dependent. The evidence suggests that flgM is also transcribed from an upstream promoter because of the presence of faint ladders of abortive primer extension products that extend to the top of the sequencing gel. There is one other relatively large intergenic gap (175 bp) in region 2, which occurs between fliJ and fliK. Using fliK-derived primers, a ladder of prominent primer extension products was observed on sequencing gels. This evidence suggests that fliK is transcribed from upstream sequences as part of an operon. Primer extension has not proved suitable for transcriptional analysis of flaK and flaL because prominent ladders of extension products are obtained. We hypothesize that some of the products may be the result of multiple species of RNA (i.e., multiple promoter control) and some may be caused by premature termination due to RNA secondary structure (i.e., a potential rho-independent terminator is found between flaK and flaL).

FIG. 6.

Primer extension analysis of mot gene transcription. RNA was prepared from the wild-type strain BB22 after growth in HI broth (B) or on HI plates (P). The amount of RNA in each lane was as follows: 1, 2 μg (P); 2, 12 μg (P); 3, minus RNA; 4, 2 μg (P); 5, minus RNA; 6, minus RNA; 7, 2 μg (B); and 8, 5 μg (P). Lanes g, a, t, and c correspond to the dideoxy nucleotide used in the sequencing reactions. Sequence and primer extension products were generated with motA-, motX-, or motY-specific primers. The oligonucleotide primers were motA (5′-CCACCGATCAAACCTATTAGGGTTGC-3′), motX (5′-CAGTAACAGTGAAGCAGCCACTG-3′), and motY (5′-GTTATCAGCCATTTATTCATC-3′).

DISCUSSION

The compilation of the repertoire of polar flagellar and chemotaxis genes of V. parahaemolyticus represents a wealth of useful information pertinent to flagellar assembly, sheath formation, polar placement, and perhaps even the connection of flagellation with the cell cycle. In addition, because the polar flagellum of V. parahaemolyticus appears to act a mechanosensor (34), an understanding of polar flagellar structure and regulation is critical for gaining insight into the mechanism of surface sensing and swarmer cell development.

Flagellar assembly.

Flagella are assembled via a type III export pathway. No consensus flagellar export signal has been defined, although a number of models have been proposed, and it seems likely that classes of sequentially exported proteins exist (8). Since V. parahaemolyticus can simultaneously assemble the lateral and polar flagella, it is an ideal system to study type III secretion determinants and the specificity of export. The sequence divergence observed between the N terminus of many (but not all) of the predicted polar V. parahaemolyticus structural proteins, as well as for the predicted chaperone-like molecules and FlgM, and components of the lateral V. parahaemolyticus system and flagellar systems of other bacteria may not only allow discernment of classes of export substrates but will also provide a system for testing potential signals.

Sheath formation and the basal body complex.

Little is known about the formation or function of flagellar sheaths, which are found in many bacteria, including marine Vibrio species, V. cholerae, Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, and Helicobacter pylori (reviewed in reference 59). These sheaths appear to be extensions of the cell outer membrane, although their composition suggests that the sheath forms a distinct, stable membrane domain. Moreover, some evidence suggests that the polar basal body structure differs from peritrichously inserted basal bodies. Two models for the basal organelle of polar flagella have been derived from electron microscopy studies of V. cholerae (sheathed), Campylobacter fetus (unsheathed), Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus (sheathed), and Wolinella succinogenes (unsheathed) (12, 13, 61). Regardless of whether the flagellum is sheathed or unsheathed, all of the studies report the existence in the basal body complex of a large convex disk situated below the outer membrane. We have also seen this disk with V. parahaemolyticus (unpublished observation). One model suggests that the disk is the P-ring equivalent (acting as the bushing associated with peptidoglycan) and that the L ring (lipopolysaccharide associated) is not present. The second model places the large disk between the P and L rings. Thus, the identity of the genes encoding basal body parts of a polar flagellum is of interest. We have found a locus encoding the V. parahaemolyticus genes for basal body and hook components. Genes for both the L and the P ring exist, providing genetic support for the second model. Whereas the V. parahaemolyticus P ring displays homology with other P rings over the full length of the protein, the N terminus of the V. parahaemolyticus L ring (FlgH) is divergent. The L ring protein of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium has been shown to be a lipoprotein and postulated to anchor the basal body in the outer membrane (54). Perhaps the nature of this protein is key to understanding differences between sheathed and unsheathed flagella. Such a possibility awaits further analysis, particularly biochemical elucidation of the N terminus of V. parahaemolyticus FlgH.

Polar flagellar placement.

One pair of genes not found in E. coli includes flhF and flhG (region 2). The flhF gene was first discovered in B. subtilis, where it was demonstrated to be required for motility (7). A nonpolar, null mutation in flhF produced nonmotile cells lacking flagella. FlhF shows homology to FtsY, which is a GTP-binding protein involved in the signal recognition particle targeting pathway. Intriguingly, the V. parahaemolyticus polar homolog contains an insertion of ∼170 aa that is not found in other homologs. The inserted domain shows homology to a eukaryotic sodium channel. It is tempting to speculate that the insertion is unique for sodium-type flagella because all of the FlhF sequences deposited in GenBank are derived from organisms that possess proton-driven flagella. Located 15 bp downstream of V. parahaemolyticus flhF is flhG, which encodes a protein that shows homology to MinD, a membrane ATPase involved in septum site determination. Perhaps FlhF and FlhG work as a pair to determine site selection of flagellar insertion. The FlhF-FlhG pair is found in a number of polarly flagellated bacteria. In P. aeruginosa, a mutation in flhG was recently shown to increase the number of polar flagella (9). It should be noted that the gene encoding ς28 is immediately downstream of flhG; in fact, translation appears to be coupled for the coding regions of flhG and fliA overlap by 10 bp.

Chemotaxis.

Mutations in two distinct loci produced chemotaxis-defective strains. Possessing different kinds of upstream controlling elements, the two che clusters appear to occur in different classes of the hierarchy. One locus in region 2 encodes most of the major cytoplasmic chemotaxis proteins, i.e., CheY, CheZ, CheA, CheB, and CheW. It seems likely that these genes are under the control of ς54 since they are very tightly linked to each other in a potential operon initiating with flhA. The second cluster, which occurs in region 1, encodes CheB and a hybrid CheY-CheW protein, similar to CheV of B. subtilis (51). Transcription of cheV clearly initiates at ς28-type promoter sequences. Although we know that che mutations in region 2 affect polar and lateral motility (53) and that che lesions in region 1 perturb polar motility, the roles that region 1 che genes play in modulating lateral motility remain to be determined. Perhaps the region 1 che genes are dedicated to the polar system.

Additional ORFs.

Three additional ORFs were found within the region 2 che locus. Two encode potential proteins of unknown function and the third encodes a protein that resembles Soj of B. subtilis and other chromosome-partitioning ATPases. In B. subtilis, Soj plays a role in cell cycle progression by coupling chromosome segregation to development (55). It seems curious that a Soj-like protein exists within a flagellum-chemotaxis operon and that this particular arrangement is found in other bacteria, e.g., P. aeruginosa and P. putida. Perhaps these novel ORFs will provide the key for a similar linkage between cell division and flagellation or development.

The polar flagellar hierarchy.

Analysis of motility mutant phenotypes provides some insight into the hierarchy of V. parahaemolyticus polar flagellar gene control and assembly. We have previously shown that mutants with defects in any of the four polar motor genes produce flagella, whereas mutants with defects in the switch genes do not (6). Switch genes are known to be required for flagellar assembly, rotation, and chemotaxis (66). The switch genes are found in region 2 along with other genes known to participate in the flagellar assembly and export pathway. Mutants with defects in the flhBA interval, which encodes components of the export apparatus, displayed the same phenotype as switch mutants, i.e., they were nonmotile, nonflagellated, and unable to synthesize flagellin. Most of these genes in region 2 are tightly linked. Precedence for large motility operons has been established in other bacteria, e.g., Borrelia burgdorferi (15). Primer extension analysis identified a potential ς54-dependent promoter preceding fliE. We postulate genes in the fliE-flhB region constitute a large flagellar operon. Downstream of flhB and preceding flhA, there is a relatively large intergenic region (230 bp). Primer extension analysis identified a promoter region, and these sequences also resembled the canonical ς54-dependent promoter.

Much of region 1 contains hook, hook-associated, and basal body genes, which also appear to be under control of ς54-like promoters preceding flgB and flgK. Mutants with defects in the hook and basal body genes yielded unexpected phenotypes. Slow radial expansion could be detected after prolonged incubation of motility plates, and some flagellin antigen was produced. We hypothesize some lateral flagellar structural parts may be able to partially substitute for loss of some polar structural components; however, substitution does not seem to be highly effective because only a few cells in each population appeared motile in the microscope. Possibly, cross-functionality of polar and lateral parts is very poor, or lateral proteins are limiting because of the genetic background of strain LM1017. Region 1 also contains the gene encoding flgM, the anti-ς28 factor. In S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, flgM is controlled by two promoters (16); this appears to be the case in V. parahaemolyticus as well. Transcription initiates immediately upstream of flgM near ς28-like sequences. Faint primer extension ladders suggest that the gene may also be cotranscribed with the upstream gene, flgA.

ς54-dependent regulation of flagellar genes is consistent with observations in other organisms. Flagellation in V. alginolyticus, V. cholerae, V. anguillarum, and P. aeruginosa has been shown to require the rpoN gene, which encodes ς54 (23, 25, 47, 63). Moreover, genes encoding ς54-type regulators exist in V. parahaemolyticus, i.e., flaK and flaM, as well as in the above-mentioned organisms (3, 25, 50, 60). FlaL resembles a two-component sensor; FlaK and FlaM resemble two-component response regulators that show homology to each other except in their C-terminal, putative DNA-binding domains. Their precise regulatory roles remain to be defined, and they may play unique roles with respect to signal input and/or output in different organisms. For example, flaK contributes to, but is not required for, motility in V. parahaemolyticus (60), whereas it appears to be essential for motility in V. cholerae and P. aeruginosa (3, 25).

To summarize, one level of polar flagellar gene transcription appears to be controlled in a ς54-dependent manner. We define the consensus promoter structure for this class of flagellar genes to be TGGC n7 TTGC n11 +1. Some of the genes in the ς54-type class are dedicated to assembly of the hook-basal body structure. Additionally, one finds the motor gene motY, hook-associated proteins 1 and 3, chemotaxis genes, and fliA, encoding ς28. In turn, this alternative sigma factor appears to be specific for the other large subset of flagellar promoters. We define the promoter structure for this class to be CTAAAG n14 G(C/T)CG(A/T)TAA n7 +1, which compares favorably with the recently revised structure of the ς28-dependent flagellar promoters of E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (TAAAGTTT n11 GCCGATAA) (19). The genes under this level of control encode additional motor parts (MotA, MotB, and MotX), chemotaxis proteins, the distal capping protein HAP2, FlgM, putative flagellar chaperones, and five flagellins.

Summary.

Thus, there are common themes in polar flagellar gene organization and regulation, but there also appear to be unique variations. The differences may reflect the lifestyle of each organism. For example, the organization of the multiple polar flagellin genes in V. parahaemolyticus is similar to loci in V. anguillarum and V. cholerae (24, 43). In these organisms, only one specific flagellin is required for motility, and its expression is under ς54-dependent control, whereas the other flagellin genes are dispensable and require ς28. The critical flagellin gene of V. anguillarum and V. cholerae is most equivalent with respect to gene location and the predicted protein sequence to V. parahaemolyticus flaC. The flaC gene is also under different environmental control from the other V. parahaemolyticus polar flagellins, which have ς28-dependent promoters. However, this gene is not essential for motility, and its regulation is not directed by ς54. The promoter structure of the flaC flagellin-encoding gene is unusual, and expression is controlled in a surface-dependent manner. What this means with respect to polar flagellar function and regulation and in the context of growth on surfaces and swarmer cell differentiation remains to be investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Deborah Noack for pioneering our primer extension studies, Jodi Enos-Berlage, Sandford Jaques, and Bonnie Stewart for helpful discussions, and the DNA Core of the University of Iowa for excellent support.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM43196 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizawa S-I, Kubori T. Bacterial flagellation and cell division. Genes Cells. 1998;3:625–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora S W, Ritchings B W, Almira E C, Lory S, Ramphal R. A transcriptional activator, FleQ, regulates mucin adhesion and flagellar gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a cascade manner. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5574–5581. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5574-5581.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belas R, Simon M, Silverman M. Regulation of lateral flagella gene transcription in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:210–218. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.210-218.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair D F. How bacteria sense and swim. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:489–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boles B R, McCarter L L. Insertional inactivation of genes encoding components of the sodium-type flagellar motor and switch of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1035–1045. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.1035-1045.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter P B, Hanlon D W, Ordal G W. flhF, a Bacillus subtilis flagellar gene that encodes a putative GTP-binding protein. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2705–2713. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chilcott G S, Hughes K T. The type III secretion determinants of the flagellar anti-transcription factor, FlgM, extend from the amino-terminus into the anti-sigma 28 domain. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:1029–1040. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasgupta N, Arora S K, Ramphal R. fleN, a gene that regulates flagellar number in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:357–364. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.357-364.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ditty J L, Grimm A C, Harwood C S. Identification of a chemotaxis gene region from Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;159:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domian I J, Reisenauer A, Shapiro L. Feedback control of a master bacterial cell-cycle regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6648–6653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelhardt H, Schuster S C, Baeuerlein E. An archimedian spiral: the basal disk of the Wolinella flagellar motor. Science. 1993;262:1046–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.8235620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferris F G, Beveridge T J, Marceau-Day M L, Larson A D. Structure and cell envelope associations of flagellar basal complexes of Vibrio cholerae and Campylobacter fetus. Can J Microbiol. 1984;30:322–333. doi: 10.1139/m84-048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser G M, Bennett J C, Hughes C. Substrate-specific binding of hook-associated proteins by FlgN and FliT, putative chaperones for flagellum assembly. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:569–580. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge Y, Charon N W. Identification of a large motility operon in Borrelia burgdorferi by semi-random PCR chromosome walking. Gene. 1997;189:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00848-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillen K L, Hughes K T. Transcription from two promoters and autoregulation contribute to the control of expression of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellar regulatory gene flgM. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7006–7015. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.7006-7015.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmann J D. Alternative sigma factors and the regulation of flagellar gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2875–2882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes K T, Gillen K L, Semon M J, Karlinsey J E. Sensing structural intermediates in bacterial flagellar assembly by export of a negative regulator. Science. 1993;262:277–1280. doi: 10.1126/science.8235660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ide N, Ikebe T, Kutsukake K. Reevaluation of the promoter structure of the class 3 flagellar operons of Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Genes Genet Syst. 1999;74:113–116. doi: 10.1266/ggs.74.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iino T, Komeda Y, Kutsukake K, Macnab R M, Matsumura P, Parkinson J S, Simon M I, Yamaguchi S. New unified nomenclature for the flagellar genes of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:533–535. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.4.533-535.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikebe T, Iyoda S, Kutsukake K. Promoter analysis of the class 2 flagellar operons of Salmonella. Genes Genet Syst. 1999;74:179–183. doi: 10.1266/ggs.74.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlinskey J E, Tsui H-C T, Winkler M E, Hughes K T. Flk couples flgM translation to flagellar ring assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5384–5397. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5384-5397.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawagishi I, Nakada M, Nishioka N, Homma M. Cloning of a Vibrio alginolyticus rpoN gene that is required for polar flagellar formation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6851–6854. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6851-6854.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klose K E, Mekalanos J J. Differential regulation of multiple flagellins in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:303–316. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.303-316.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klose K E, Mekalanos J J. Distinct roles of an alternative sigma factor during both free-swimming and colonizing phases of the Vibrio cholerae pathogenic cycle. Mol Microbiol. 1998;23:501–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komeda Y. Fusions of flagellar operons to lactose genes on a Mu lac bacteriophage. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:16–26. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.1.16-26.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Komeda Y. Transcriptional control of flagellar genes in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1315–1318. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1315-1318.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kutsukake K. Autogenous and global control of the flagellar master operon, flhDC, in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;24:440–448. doi: 10.1007/s004380050437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kutsukake K, Iino T. Role of the FliA-FlgM regulatory system on the transcriptional control of the flagellar regulon and flagellar formation in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3598–3605. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3598-3605.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kutsukake K, Ohya Y, Iino T. Transcriptional analysis of the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:741–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.741-747.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Matsumura P. Differential regulation of multiple overlapping promoters in flagellar class II operons in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:613–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macnab R M. Flagella and motility. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Gross C A, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B Jr, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macnab R M. The bacterial flagellum: reversible rotary propellor and type III export apparatus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7149–7153. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7149-7153.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarter L, Hilmen M, Silverman M. Flagellar dynamometer controls swarmer cell differentiation of V. parahaemolyticus. Cell. 1988;54:345–351. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarter L L. MotY, a component of the sodium-type flagellar motor. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4219–4225. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4219-4225.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCarter L L. MotX, a channel component of the sodium-type flagellar motor. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5988–5998. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.5988-5998.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarter L L. Genetic and molecular characterization of the polar flagellum of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1595–1609. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1595-1609.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarter L L. OpaR, a homolog of Vibrio harveyi LuxR, controls opacity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 1999;180:3166–3173. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3166-3173.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarter L L. The multiple identities of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;1:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarter L L, Silverman M. Phosphate regulation of gene expression in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3441–3449. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3441-3449.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCarter L L, Silverman M. Iron regulation of swarmer cell differentiation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:731–736. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.731-736.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCarter L L, Wright M E. Identification of genes encoding components of the swarmer cell flagellar motor and propeller and a sigma factor controlling differentiation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3361–3371. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3361-3371.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGee K, Horstedt P, Milton D L. Identification and characterization of additional flagellin genes from Vibrio anguillarum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5188–5198. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5188-5198.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohnishi I, Kutsukake K, Suzuki H, Iino T. Gene fliA encodes an alternative sigma factor specific for flagellar operons in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:1139–1147. doi: 10.1007/BF00261713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohnishi I, Kutsukake K, Suzuki H, Iino T. A novel transcriptional regulatory mechanism in the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium: an anti-sigma factor inhibits the activity of the flagellum-specific sigma factor ςF. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3149–3157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohta M, Newton A. Signal transduction in the cell cycle regulation of Caulobacter differentiation. Trends Microbiol. 1996;8:326–332. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Toole R, Milton D L, Horstedt P, Wolf-Watz H. RpoN of the fish pathogen Vibrio (Listonella) anguillarum is essential for flagellum production and virulence by the water-borne but not intraperitoneal route of inoculation. Microbiology. 1997;43:3849–3859. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pruss B M, Matsumura P. A regulator of the flagellar regulon of Escherichia coli, flhD, also affects cell division. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:668–674. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.668-674.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pruss B M, Matsumura P. Cell cycle regulation of flagellar genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5602–5604. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5602-5604.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ritchings B W, Almira E C, Lory S, Ramphal R. Cloning and phenotypic characterization of fleS and fleR, new response regulators of Pseudomonas aeruginosa which regulate motility and adhesion to mucin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4868–4876. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4868-4876.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosario M M L, Fredrick K L, Ordal G, Helmann J. Chemotaxis in Bacillus subtilis requires either of two functionally redundant CheW homologs. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2736–2739. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2736-2739.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sar N, McCarter L, Simon M, Silverman M. Chemotactic control of the two flagellar systems of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:334–341. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.334-341.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schoenhals G J, Macnab R M. Physiological and biochemical analyses of FlgH, a lipoprotein forming the outer membrane L ring of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4200–4207. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4200-4207.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharpe M E, Errington J. The Bacillus subtilis soj-spo0J locus is required for a centromere-like function involved in prespore chromosome partitioning. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shingler V. Signal sensing by ς54-dependent regulators: derepression as a control mechanism. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:409–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.388920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Silverman M, Matsumura P, Simon M. The identification of the mot gene product with Escherichia coli-lambda hybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.9.3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silverman M, Showalter R, McCarter L. Genetic analysis in Vibrio. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:515–536. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04026-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sjoblad R D, Emala C W, Doetsch R N. Bacterial sheaths: structures in search of function. Cell Motility. 1982;3:93–103. doi: 10.1002/cm.970030108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stewart B J, McCarter L L. Vibrio parahaemolyticus FlaJ, a homologue of FliS, is required for production of a flagellin. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:137–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomashow L S, Rittenberg S C. Waveform analysis and structure of flagella and basal complexes from Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus 109J. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:1038–1046. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.1038-1046.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Totten P A, Lara J C, Lory S. The rpoN gene product of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is required for expression of diverse genes, including the flagellin gene. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:389–396. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.389-396.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Woo T H S, Cheng A F, Ling J M. An application of a simple method for the preparation of bacterial DNA. BioTechniques. 1992;13:696–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu J, Newton A. Regulation of the Caulobacter flagellar gene hierarchy: not just for motility. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:233–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3281691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamaguchi S, Fujita H, Ishihara A, Aizawa S-I, Macnab R M. Subdivision of flagellar genes of Salmonella typhimurium into regions responsible for assembly, rotation, and switching. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:187–193. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.187-193.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yokoseki T, Iino T, Kutsukake K. Negative regulation by fliD, fliS, and fliT of the export of the flagellum-specific anti-sigma factor, FlgM, in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:899–901. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.899-901.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]