Abstract

Cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis is an immune complex-mediated vasculitis with a myriad of clinical manifestations. We report a rare case of a patient in her 60s with rheumatoid arthritis who presented with fever of unknown origin, cutaneous leucocytoclastic vasculitis and progressive pulmonary infiltrates with cavitation. Extensive investigation for an infectious aetiology was unrevealing. Blood investigations revealed high-titre rheumatoid factor, hypocomplementaemia, raised inflammatory markers and the presence of type 2 cryoglobulins. A diagnosis of cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis with pulmonary involvement was made, and the patient was treated with high-dose prednisolone and rituximab, which resulted in complete resolution of lung changes and marked clinical improvement. This case highlights the rarity of lung involvement, including cavitation in cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis.

Keywords: Vasculitis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Connective tissue disease, Rheumatology, Respiratory medicine

Background

Cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis is a small-sized to medium-sized vessel vasculitis commonly due to lymphoproliferative disorder, paraproteinaemia, viral infections (especially hepatitis C, HIV and hepatitis B) and autoimmune diseases; including Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis.1 2 Clinical manifestation can be protean and classically present with purpura, arthralgia and weakness, Meltzer’s triad.3 We describe a case of cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis presenting with fever of unknown origin and pulmonary infiltrates and cavitation.

Case presentation

A lady in her 60s presented with a bilateral lower limb papulopurpuric rash and excisional skin biopsy showed leucocytoclastic vasculitis with isolated C3 deposition, without IgG or IgM on immunofluorescence (figure 1). She had a 5-year history of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate 20 mg once per week and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/day. There were no other vasculitic manifestations apart from the rash. Blood investigations showed raised inflammatory markers: erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 33 mm/hour (normal, <20 mm/hour), C reactive protein (CRP) of 45 mg/L (normal, <5 mg/L), high-titre rheumatoid factor (RF) of 447 IU/mL (normal, <20 IU/mL) and low C4, <0.07 g/L (normal, 0.13–0.41 g/L). Other investigations, including antinuclear antibody, antiproteinase 3 and antimyeloperoxidase antibodies, HIV and hepatitis screening were negative. She was treated for rheumatoid vasculitis with an isolated cutaneous manifestation and given a tapering course of prednisolone with the resolution of the rash after 2 months. While on prednisolone 10 mg/day, she presented with a history of fever and lethargy for 1 week with a documented fever up to 39°C. There was no apparent source of infection and systemic review was unremarkable. Physical examination findings were unremarkable with no vasculitic rash or peripheral joint synovitis. There was no clinical focus of infection, no peripheral stigmata of endocarditis and no focal chest signs.

Figure 1.

Papulopurpuric rashes seen over the limbs (A). Skin biopsy (B) shows the presence of perivascular (*) mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the superficial dermis with associated leucocytoclastic debris and extravasated red blood cells. The infiltrate consists of lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils and conspicuous eosinophils.

Investigations

Sputum culture grew a sensitive strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae, and all other cultures, including interferon gamma release assay for tuberculosis and infective serologies, were negative. She was treated with multiple broad-spectrum antibiotics, including carbapenem, but continued to clinically deteriorate with persistent fever and rising inflammatory markers with a CRP up to 197 mg/L. A CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis performed after 1 week of antibiotics was normal. In particular, no explanation for the fever was seen. A second CT scan performed 1 week later showed a new left lower lobe cavitating lesion measuring 3.6×3.1 cm with a thickened surrounding rind (figure 2). A third interval CT scan performed 1 week later showed new ground-glass infiltrates in the upper zones bilaterally but a reduction in cavity size to 2.8×1.6 cm (figures 3 and 4). At this time, she developed a new purpuric rash over the right upper limb, and repeated blood investigations showed a rising RF titre to 1208 IU/mL and marked hypocomplementaemia, C4 of <0.07 g/L and C3 of 0.43 g/L (normal, 0.74–1.57 g/L), suggestive of cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis. A serum cryoglobulin was detected—an IgM kappa with a polyclonal IgG kappa paraprotein consistent with type 2 cryoglobulinaemia (cryocrit 2%).

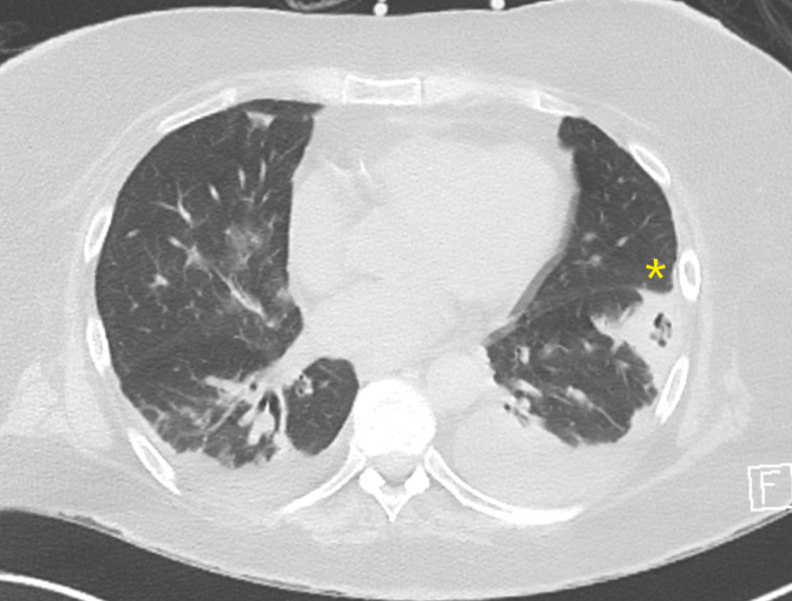

Figure 2.

CT of the thorax. Axial view showing new subpleural opacity (*) in the left lower lobe with central lucency, in keeping with cavitation measuring 3.6×3.1 cm with a thickened surrounding rind.

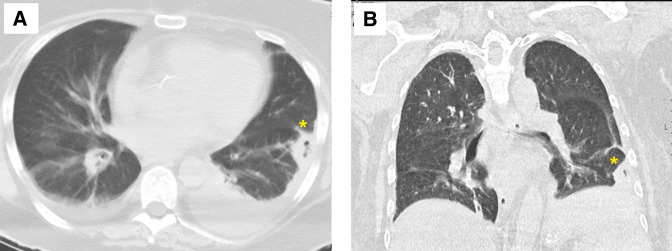

Figure 3.

Views of the CT of the thorax (A, axial; B, coronal) showing the decreased size of the thick-walled cavitating lesion(*) measuring 2.8×1.6 cm and bilateral small pleural effusion.

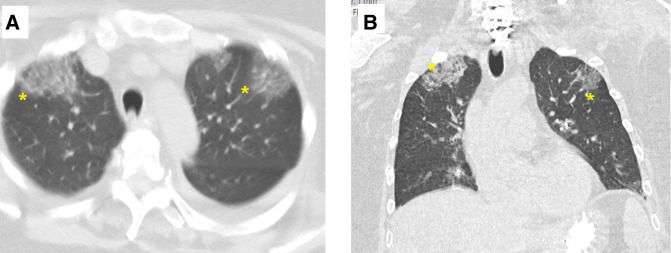

Figure 4.

Views of the CT of the thorax views (A, axial; B, coronal) showing new bilateral anterior upper lobe ground-glass infiltrates(*).

Treatment

The patient was commenced on oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg, and within 10 days, her clinical condition had significantly improved with a marked reduction in RF titre and inflammatory markers to 811 IU/mL and CRP of 28 mg/L, respectively.

Outcome and follow-up

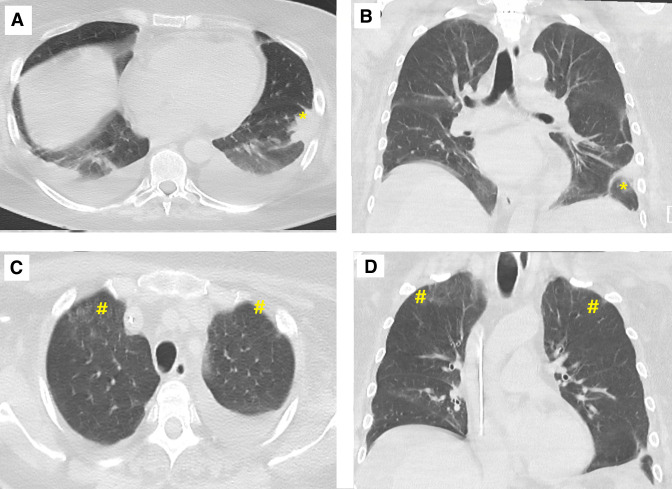

A repeat CT of the chest showed complete resolution of the cavitating lesion and ground-glass opacities (figure 5). A final diagnosis of cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis with pulmonary involvement was made. She received intravenous rituximab 1 g, weeks 0 and 2 with good clinical response, and concurrent methotrexate 25 mg/week with no recurrence of pulmonary symptoms at 4 months of follow-up.

Figure 5.

Views of the CT of the thorax views showing resolution of previously seen left lower lobe (*) cavitation (A, axial; B, coronal) and ground-glass (#) infiltrates over the upper zone (C, axial; D, coronal).

Discussion

Cryoglobulinaemia refers to the presence of immunoglobulin that precipitates in vitro at low temperatures and dissolves when rewarmed. There are three main classes of cryoglobulins: type 1 and mixed cryoglobulins (types 2 and 3) based on the Brouet classification.4 Cryoglobulinaemia can be asymptomatic or produce disease by causing vascular occlusion, hyperviscosity syndrome or cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis.1

Many clinical manifestations have been described especially arthralgia, arthritis, weakness, peripheral neuropathy, Raynaud’s phenomenon, renal involvement, purpura, ulcers and gastrointestinal manifestation such as abdominal pain or gastrointestinal haemorrhage.1 2 5 Pulmonary involvement is rare but can include dyspnoea, pleuritic chest pain, haemoptysis and imaging findings of migratory interstitial infiltrates, fibrosis, organising pneumonia and diffuse alveolar haemorrhage.2 5

A retrospective study by Trejo et al2 of 443 patients with cryoglobulinaemia found only 206 (47%) patients had a symptomatic disease. Pulmonary involvement (pulmonary infiltrates, fibrosis or haemoptysis) and fever were seen in only 9 (2%) and 21 (5%) patients, respectively.2

The pulmonary involvement seen in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis provides an insight into the spectrum of vasculitic lung manifestations, including cavitation, migratory interstitial infiltrates, consolidation, organising pneumonia and alveolar haemorrhage.5–8 The archetype is granulomatosis with polyangiitis in which lung nodules or consolidation can range from a few millimetres to more than 10 cm in diameter with cavitation. The cavities are frequently thick-walled, resulting in a CT halo sign, a rim of ground-glass opacities encircling the pulmonary lesion and reduces in size with treatment.5–8 A thick-rimmed cavity was seen in our patient (figure 2).

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one other case report of cavitation in cryoglobulinaemia. Zackrison and Katz9 reported a 75-year-old male patient with cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis who presented with recurrent migratory pulmonary infiltrates, which progressed to cavitary lesions. Lung biopsy demonstrated bronchiolitis obliterans with organising pneumonia. There was complete resolution of the lung lesions with glucocorticoids.9

Kim et al reported a 75-year-old man with mixed cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis presenting with progressive dyspnoea and CT evidence of multifocal consolidation with a lung biopsy consistent with organising pneumonia. Resolution of symptoms occurred with corticosteroid therapy.10

In our case, lung biopsy was not pursued as the patient was deemed to be at high risk for the procedure. The lung parenchymal infiltrates most likely represented organising pneumonia. Organising pneumonia can appear as ground-glass infiltrates or consolidation.5 11 Focal organising pneumonia can appear as a nodule, mass or even cavitations.11 Important differentials for migratory multifocal peripheral consolidations include organising pneumonia, eosinophilic pneumonia, pulmonary haemorrhage and pulmonary vasculitis.5 11

The major obstacle in making the diagnosis would be the exclusion of infectious causes for the clinical presentation. Certain infections can trigger transient appearance cryoglobulinaemia mostly asymptomatic, for instance, hepatitis B, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, Coxiella burnetii, parvovirus B19, tuberculosis and brucellosis.12 Hence, in a patient with cavitating lung infiltrates, the real dilemma is determining if the lesions are attributable to cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis or represent a cavitating lung infection giving rise to transient asymptomatic cryoglobulinaemia. A high index of suspicion is the key in making such a diagnosis, as delays in recognition could result in morbidity and mortality. In our case, the clinical deterioration of the patient despite broad-spectrum antibiotics and the evolution of lung infiltrates in the setting of negative cultures favoured a non-infective inflammatory process. Important surrogate markers for cryoglobulinaemia include the presence of RF and complement consumption, especially C4.

Learning points.

Cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis is a challenging diagnosis to make as it requires a high index of suspicion, and the presence of rheumatoid factor with predominant low C4 acts as a surrogate marker in mixed cryoglobulinaemia.

Patients presenting with undifferentiated constitutional symptoms with raised inflammatory markers in the absence of infection should be evaluated for cryoglobulinaemia.

This case highlights the rare manifestation of cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis with pulmonary infiltrates and cavitation.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM was the lead author involved in the design, drafting of the manuscript and patient management. PW and BN were the consultants leading the clinical management of the patient, as well editing the manuscript. NM was involved in the design and editing of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Muchtar E, Magen H, Gertz MA. How I treat cryoglobulinemia. Blood 2017;129:289–98. 10.1182/blood-2016-09-719773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trejo O, Ramos-Casals M, García-Carrasco M, et al. Cryoglobulinemia. Medicine 2001;80:252–62. 10.1097/00005792-200107000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meltzer M, Franklin EC, Elias K, et al. Cryoglobulinemia—A clinical and laboratory study. Am J Med 1966;40:837–56. 10.1016/0002-9343(66)90200-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouet JC, Clauvel JP, Danon F, et al. Biologic and clinical significance of cryoglobulins. A report of 86 cases. Am J Med 1974;57:775–88. 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90852-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castañer E, Alguersuari A, Gallardo X, et al. When to suspect pulmonary vasculitis: radiologic and clinical clues. Radiographics 2010;30:33–53. 10.1148/rg.301095103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee KS, Kim TS, Fujimoto K, et al. Thoracic manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis: CT findings in 30 patients. Eur Radiol 2003;13:43–51. 10.1007/s00330-002-1422-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohrmann C, Uhl M, Kotter E, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of Wegener granulomatosis: CT findings in 57 patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Radiol 2005;53:471–7. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komócsi A, Reuter M, Heller M, et al. Active disease and residual damage in treated Wegener's granulomatosis: an observational study using pulmonary high-resolution computed tomography. Eur Radiol 2003;13:36–42. 10.1007/s00330-002-1403-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zackrison L, Katz P. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia associated with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arthritis & Rheumatism 1993;36:1627–30. 10.1002/art.1780361119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YJ, Kim SH, Kim TH. A case of organizing pneumonia with cryoglobulinemia. The Korean Journal of Medicine 2009;77:1183–7 https://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO200910103442629.page [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epler GR. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:158. 10.1001/archinte.161.2.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos-Casals M, Stone JH, Cid MC, et al. The cryoglobulinaemias. Lancet 2012;379:348–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60242-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]