Abstract

Objective

Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is a common complication affecting approximately one-third of patients after cardiac surgery and valvular interventions. This umbrella review systematically appraises the epidemiological credibility of published meta-analyses of both observational and randomised controlled trials (RCT) to assess the risk and protective factors of POAF.

Methods

Three databases were searched up to June 2021. According to established criteria, evidence of association was rated as convincing, highly suggestive, suggestive, weak or not significant concerning observational studies and as high, moderate, low or very low regarding RCTs.

Results

We identified 47 studies (reporting 61 associations), 13 referring to observational studies and 34 to RCTs. Only the transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) approach was associated with the prevention of POAF and was supported by convincing evidence from meta-analyses of observational data. Two other associations provided highly suggestive evidence, including preoperative hypertension and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio. Three associations between protective factors and POAF presented a high level of evidence in meta-analyses, including RCTs. These associations included atrial and biatrial pacing and performing a posterior pericardiotomy. Nineteen associations were supported by moderate evidence, including use of drugs such as amiodarone, b-blockers, glucocorticoids and statins and the performance of TAVR compared with surgical aortic valve replacement.

Conclusions

Our study provides evidence confirming the protective role of amiodarone, b-blockers, atrial pacing and posterior pericardiotomy against POAF as well as highlights the risk of untreated hypertension. Further research is needed to assess the potential role of statins, glucocorticoids and colchicine in the prevention of POAF.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42021268268.

Keywords: Meta-Analysis, Atrial Fibrillation, Cardiac Surgical Procedures, Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement, Risk Factors

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is a common complication after cardiac surgery and valvular interventions.

Numerous risk factors for POAF have been identified, but there is no credibility assessment.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Only a few identified risk factors and protective factors of POAF were supported by high-level evidence; namely, amiodarone, b-blockers, atrial pacing and posterior pericardiotomy against POAF as protective factors and untreated hypertension as a risk factor.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study provides a broad picture of the non-genetic risk factors associated with the risk for POAF and evaluates their level of evidence across published meta-analyses.

These findings allow for robust classifications that can be used for future policymaking and future studies on POAF prevention.

Introduction

Acute or new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF) in the immediate postoperative period is classified as postoperative AF (POAF).1 POAF is a common complication affecting over 30% of patients following cardiac surgery or valvular intervention.2 3 AF episodes after cardiac surgery are typically brief and self-terminating,4 with the highest incidence occurring between days 2 and 4 after cardiac surgery.5 POAF is an independent risk factor for numerous adverse events, including increased risk of stroke, prolonged hospital stays and a doubling of all-cause mortality.3 6

Identifying and targeting modifiable risk factors may reduce the risk of POAF. However, risk prediction for POAF is complex. Propensity for POAF is due to a combination of preoperative, perioperative and postoperative factors.3 Predisposing factors such as age, left ventricular dysfunction, hypertension and left atrial enlargement are strongly associated with POAF.5 7 Local inflammation associated with surgical lesions and postoperative pericarditis,3 8 9 prolonged mechanical ventilation, pulmonary infections and electrolyte imbalances also appear to be linked to POAF.4 5 7 Moreover, adrenergic activation seems to be involved: the use of inotropic drugs increases the risk for POAF, while b-blockers reduce this risk.5 10

Although numerous meta-analyses on risk factors for POAF have been published, there is still no complete and concise summary of the research. Thus, the prevention and management of POAF after cardiac surgery and cardiac interventions remain a major challenge.

We aimed to summarise the existing evidence on risk and protective factors associated with POAF among published meta-analyses through an umbrella review. An umbrella review is a systematic collection, evaluation and synthesis of the existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses on a specific topic.11 It can be applied to provide a comprehensive picture of risk and protective factors for a specific disease and has already been implemented in several clinical entities.12 13 Using standardised methods used in umbrella review, we ranked the evidence from existing meta-analyses on POAF according to sample size, strength of the association and the presence of various biases.11 14

Methods

Data selection, search strategy and selection criteria

In this study, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses15 reporting guidelines and the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines16 (online supplemental appendix 1) were followed. An a priori protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database.

openhrt-2022-002074supp001.pdf (285.9KB, pdf)

Bibliographic databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane review and Cochrane database of clinical trials) were searched from inception through 28 May 2021, to identify systematic reviews with meta-analysis of observational or randomised controlled trials (RCT) examining associations between non-genetic risk or protective factors and risk for POAF. The search algorithm used was broad to identify all eligible studies with terms related to AF and meta-analysis and is presented in online supplemental appendix 2. Reference lists from eligible studies were also hand searched to identify additional studies.

Two researchers (DK and MS) independently searched for eligible articles. The same researchers examined the full texts of the recovered articles for eligibility. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussions with a third researcher (EC).

We included only meta-analyses of observational studies with a cohort, case–control or nested case–control study design and RCTs. Whenever multiple meta-analyses assessed the same risk or protective factor, we included only the meta-analysis with more studies.17 All reported outcomes were considered for inclusion.

We excluded meta-analyses with (1) study designs other than the ones stated before (eg, cross-sectional), (2) a non-systematic selection of the included studies, or non-systematic reviews, (3) examining genetic variants of AF, (4) studies published in non-English language, (5) insufficient data for quantitative synthesis or (6) study-specific effect estimates for continuous exposures were reported as mean difference rather than relative risk (RR) measures, such as OR, HR, RR. The reasons for exclusion after a full-text review are presented in the supplementary material (online supplemental etable 1, Appendix 3).

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two researchers (DK and MS) using a predefined extraction form (EXCEL 365). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. The extracted data included information on the first author’s name, year of publication, journal, standard identifier (DOI), number of component studies, total sample size and the risk or protective factors assessed, with the RR estimate (such as OR, HR, RR), alongside with their 95% CIs. For each component study, we collected the first author’s name, year of publication, study design, sample size (exposure and non-exposure) and the RR estimates (ie, HR, OR, RR) with the corresponding 95% CI.

Quality assessment

The RoB per included meta-analysis was assessed using the MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR2) tool (available at https://amstar.ca/Amstar-2.php). This tool appraises randomised and non-randomised studies and evaluates criteria within 10 original domains. Two reviewers (DT and MS) performed the quality assessment and checked by a third investigator in case of disagreement (EC).18

Data synthesis and analysis

We used standardised methods and state-of-the-art approaches for data synthesis and analysis in this umbrella meta-analysis.13 19 Specifically, the effect size (ES) of different studies reported in each meta-analysis were extracted, for each association, and the pooled ESs and 95% CIs were recalculated, using random-effects models.20 This was because of the expected heterogeneity, in particularly observational studies.20

Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 metric.21 I2 varies between 0% and 100% and measures the variability of ES due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error.21 An I2 value greater than 50% corresponds to substantial heterogeneity. The small study effect bias (ie, whether small studies tend to yield more significant ES than the larger ones) was evaluated using the Egger regression asymmetry test.22 A p value <0.10 was considered to provide adequate evidence for small study effects.

Finally, the excess significance bias was measured to evaluate whether more studies had statistically significant results than anticipated.23 The anticipated number of statistically significant studies per association was calculated by adding the statistical power estimates for each component study. The ES of the larger study was used (ie, the study with the smallest SE) in each meta-analysis to calculate the power of each study using a non-central t distribution. A p value ≤0.10 was considered significant for excess significance bias.23 All analyses were performed using Stata V.17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Assessment of epidemiological credibility

Relevant associations of risk and protective factors with POAF derived from observational studies were classified into five categories according to the evidentiary power of their associations: convincing (class I), highly suggestive (class II), suggestive (class III), weak (class IV) and not significant (NS) (online supplemental etable 1, appendix 4). Following previous umbrella reviews,13 we considered as convincing the associations with>1000 cases a highly significant association (p-value<1 × 10−6), no large between-study heterogeneity, no evidence of excess significance bias or small study effects, and a 95% prediction interval excluding the null value. Highly suggestive evidence needed >1000 cases, a highly significant association (p value <1×10−6 by random-effects model), and a statistically significant effect in the largest study. Suggestive evidence required>1000 cases and p value <0.001 by random-effects model. Associations with a p value >0.05 in the random-effects meta-analysis were considered non-significant.

Ιn RCTs, the credibility of evidence was categorised according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) levels of evidence (GLE) using a standardised set of rules.24 25 The evaluated areas included: (1) imprecision, by the sample size in the pooled analysis (if 100–199 participants, GLE was downgraded by one level; if <100 participants, downgraded by two levels); (2) RoB of trials, by the proportion of participants in the pooled measured to have low RoB for randomization and observer blinding (if <75% of participants had low RoB or RoB not reported, GLE was downgraded by one level); (3) inconsistency, by heterogeneity (if I² >75%, downgraded by one level) and (4) RoB of the systematic review, based on AMSTAR 2 questionnaire (if moderate quality, downgraded by one level; if low or critically low quality, downgraded by two levels). Then, the associations were graded as high, moderate, low or very low by GLE (online supplemental etable 2, appendix 4).

Patient and public involvement

No participants were involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of the research question or outcome measures.

Results

Literature search

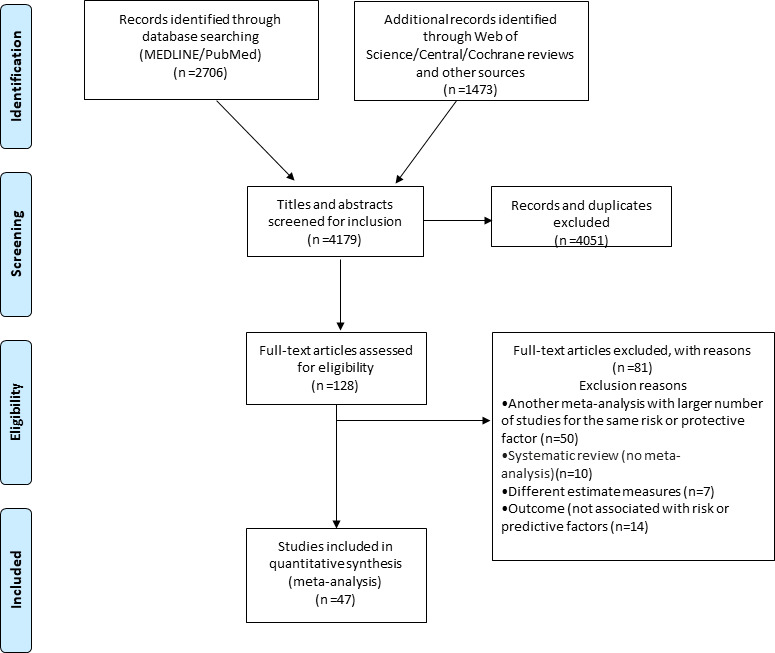

The initial search yielded 4179 publications. After evaluating titles and abstracts, 128 eligible articles were identified. Eighty-one articles were excluded after a full-text review (online supplemental etable 1, appendix 3), and 47 articles were subsequently included for analysis (13 meta-analyses of observational studies and 34 meta-analyses of RCTs, reported overall 49 associations; figure 1; online supplemental etable 1, appendix 5).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Meta-analyses of observational studies

The median number of meta-analyses included in meta-analyses of observational studies was 7.5 (IQR=4.3–11.8), the median number of participants was 4349 (IQR=1219–30 273) and the median number of cases were 1036 (IQR=343–7373).

In the meta-analyses of observational studies, 10 of the 13 studied associations (77%) had a nominally statistically significant effect (p≤0.05) under the random-effects models, and three of those (23%) achieved a p value <10-6. Seven associations (54%) had more than 1000 cases per association. Significant heterogeneity (I2>50%) was found in eight associations (62%), and only three associations (23%) had a 95% prediction interval that excluded the null value. In 10 associations (77%), the ES of the largest study had a nominally statistically significant effect (p≤0.05). Finally, small study effects were found for two associations (15%), and excess significance bias was found for four (31%).

The quality of meta-analyses of observational studies assessed by AMSTAR2 was high in five meta-analyses, moderate in five and low or critically low in three (table 1; online supplemental etable 1, appendix 5).

Table 1.

Predictors for postoperative AF, in meta-analyses of observational studies

| Author, year | Predictor | Exposed/unexposed as included in MA | k | n/N | Metric | ES (95% CI) | P | PI include null value | I2 | SSE | ESB | LS sign | CE | CES2 (n>1000) | AMSTAR 2 quality |

| Angsubhakorn 2020 | Non-transfemoral transcatheter AVR | Transfemoral transcatheter AVR or non-transfemoral AVR | 7 | 1262/5681 | RR | 2.95 (2.43 to 3.58) | 8.2×10–28 | No | 40.62 | No | No | Yes | I | I | Critically low |

| Liu 2020 | Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | High or low neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | 12 | 1330/9262 | OR | 1.39 (1.26 to 1.53) | 1.9×10–11 | No | 95.15 | No | Yes | Yes | II | II | High |

| Zhou 2017 | Preoperative hypertension | Preoperative hypertension or normotension | 25 | 92658/130087 | RR | 1.07 (1.0.5 to 1.09) | 9.1×10–15 | No | 54.88 | No | Yes | Yes | II | II | Moderate |

| Litton 2012 | Preoperative BNP/NT-proBNP | High BNP/NT-proBNP or low BNP/NT-proBNP | 4 | 530/1115 | OR | 2.89 (1.04 to 8.04) | 0.041 | Yes | 91.23 | No | No | Yes | IV | IV | Critically low |

| Phan 2016 | Obesity | Obese or not | 32 | 16608/86984 | OR | 1.21 (1.06 to 1.38) | 0.006 | Yes | 89.36 | No | Yes | No | IV | IV | High |

| Liu 2018 | Blood transfusion | Blood transfusion or not | 8 | 7491/31069 | OR | 1.55 (1.08 to 2.21) | 0.016 | Yes | 97.09 | No | Yes | Yes | IV | IV | High |

| Qaddoura 2014 | OSAS | OSAS or not | 7 | 264/700 | OR | 1.84 (1.14 to 2.96) | 0.012 | Yes | 51.69 | No | No | Yes | IV | IV | Moderate |

| Sun 2020 | RAASi | RAASi use in TAVR or not | 2 | 280/1532 | RR | 0.73 (0.59 to 0.91) | 0.004 | NP | 0.45 | NP | No | Yes | IV | IV | Moderate |

| Chen 2020 | CHA2DS2-VASC SCORE | CHA2DS2-VASc≥2 or CHA2DS2-VASc<2 | 8 | NA/NA | OR | 1.46 (1.25 to 1.72) | 3.2×10–6 | Yes | 0.000 | Yes | NA | Yes | IV | III | Moderate |

| Athanasiou 2004 | Off-pump elderly | Off-pump or not | 8 | 809/3017 | OR | 0.70 (0.51 to 0.95) | 0.022 | Yes | 49.07 | No | NP | Yes | IV | IV | Critically low |

| Guan 2020 | Off-pump | On- or off-pump CABG | 13 | 6431/31039 | OR | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.12) | 0.515 | Yes | 0.073 | No | NP | No | NS | NS | High |

| Yousuf Salmasi 2020 | Mini sternotomy | Mini-sternotomy or right anterior thoracotomy | 5 | 616/2234 | OR | 0.67 (0.25 to 1.78) | 0.425 | Yes | 91.00 | No | No | No | NS | NS | Moderate |

| Chen 2019 | RAASi | RAASi use in cardiac surgery or not | 11 | 7018/27885 | OR | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.2) | 0.368 | Yes | 67.29 | Yes | NP | Yes | NS | NS | High |

CHADS VASc: congestive heart failure, hypertension, age >75 years, diabetes, stroke, vascular disease, age >65, female sex.

OSAS: obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; AF, atrial fibrillation; AVR, aortic valve replacement; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CE, class of evidence; CES, class of evidence sensitivity analysis; ES, effect size; ESB, excess significance bias; I2, heterogeneity; K, number of studies for each factor; LS, largest study with significant effect; n, number of cases; N, total number of cohorts per factor; NA, not assessable; NP, not pertinent, because the number of observed studies is less than the expected; NR, not reported; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-natriuretic peptide; PI, prediction interval; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RR, risk ratio; SSE, small study effects.

When the criteria for the credibility of evidence were applied, one (8%) association presented convincing evidence (table 1; online supplemental etable 1, appendix 5) concerning the use of non-transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) versus transfemoral TAVR. Two other associations (15%) presented highly suggestive evidence for risk factors: preoperative hypertension and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio. The remaining seven (54%) statistically significant associations between risk or protective factors and POAF presented weak evidence (table 1; online supplemental etable 1, appendix 5), while three associations (23%) were NS (table 1; online supplemental etable 1, appendix 5). The three factors with convincing and highly suggestive evidence in the principal analysis did not change their class of evidence when the criterium with greater than 1000 cases per association was excluded (table 1).

Meta-analyses of randomised studies

The median number of studies included in meta-analyses of RCTs was 10 (IQR=4.8–13), the median number of cases was 344 (IQR=201–707) and the median number of participants was 1692 (IQR=834–2526) (table 2; online supplemental appendix).

Table 2.

Statistical significant predictors for postoperative AF, in meta-analyses of RCTs

| Author, year | Predictor | Exposed/unexposed as included in MA | k | n/N | Metric | ES (95% CI) | P | PI include null value | I2 % | SSE | ESB | LS sign | High RoB | GLE | AMSTAR 2 quality |

| Ruan 2020 | Atrial pacing | Atrial pacing or not | 21 | 511/2002 | OR | 0.57 (0.43 to 0.76) | 0.0002 | Yes | 35.04 | No | Yes | No | ≤25% | High | High |

| Ruan 2020 | Bi-atrial pacing | Bi-atrial pacing or not | 10 | 235/1014 | OR | 0.44 (0.26 to 0.76) | 0.002 | Yes | 57.55 | No | Yes | No | ≤25% | High | High |

| Hu 2016 | Posterior pericardiotomy | Posterior pericardiotomy or not | 10 | 329/1648 | OR | 0.36 (0.23 to 0.56) | 0.0000 | Yes | 56.36 | No | Yes | Yes | ≤25% | High | High |

| Liu 2019 | Dexmedetomidine | Dexmedetomidine use or not | 13 | 335/1684 | OR | 0.70 (0.49 to 0.98) | 0.037 | Yes | 29.82 | No | No | No | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Guerra 2017 | Ranolazine | Ranolazine use or not | 3 | 176/700 | OR | 0.30 (0.13 to 0.69) | 0.004 | Yes | 66.00 | No | No | Yes | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Patti 2015 | Statin pre-treatment | Statin pre-treatment or not | 11 | 303/1106 | OR | 0.41 (0.32 to 0.53) | 0.000 | Yes | 0.00 | No | NP | Yes | ≤25% | Moderate | High |

| Putzu 2016 | Perioperative statin therapy | Perioperative statin therapy or not | 19 | 1255/4737 | OR | 0.53 (0.35 to 0.81) | 0.003 | Yes | 90.90 | No | Yes | Yes | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Guo 2014 | PUFAs alone and in combination therapy with vitC+vitE | PUFAs alone and in combination therapy with vitC+vitE or not | 11 | 956/3137 | OR | 0.61 (0.44 to 0.86) | 0.005 | Yes | 68.84 | Yes | Yes | No | >25% | Moderate | Moderate |

| Guo 2014 | EPA/DHA ratio1:2 | EPA/DHA ratio1:2 or 1:2 | 11 | 956/3137 | OR | 0.61 (0.44 to 0.86) | 0.005 | Yes | 68.84 | Yes | Yes | No | >25% | Moderate | Moderate |

| Gillespie 2005 | Amiodarone | Amiodarone or not | 15 | 762/2941 | OR | 0.5 (0.42 to 0.60) | 0.0000 | No | 0.00 | No | NP | Yes | ≤25% | Moderate | Moderate |

| DiNicolantonio 2014 | Carvedilol use | Carvedilol or metoprolol use | 4 | 135/497 | OR | 0.50 (0.28 to 0.90) | 0.020 | Yes | 45.88 | No | No | No | ≤25% | Moderate | High |

| Li 2015 | Landiolol | Landiolol use or not | 9 | 217/807 | RR | 0.40 (0.30 to 0.53) | 0.0000 | No | 20.15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Ho 2009 | Hydrocortisone | Hydrocortisone use or not | 18 | 455/1509 | RR | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.86) | 0.0002 | No | 0.00 | No | No | Yes | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Geng 2017 | Perioperative antioxidant therapy | Perioperative antioxidant therapy use or not | 11 | 464/1544 | RR | 0.55 (0.42 to 0.72) | 0.0000 | Yes | 54.44 | Yes | Yes | Yes | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Lennerz 2017 | Colchicine | Colchicine use or not | 5 | 354/1744 | RR | 0.66 (0.52 to 0.85) | 0.001 | Yes | 24.68 | No | No | No | >25% | Moderate | Moderate |

| Liu 2014 | Prophylactic NAC use | Prophylactic NAC use or not | 10 | 253/1026 | OR | 0.56 (0.38 to 0.83) | 0.004 | Yes | 14.06 | No | No | No | ≤25% | Moderate | Critically low |

| Langlois 2017 | PUFA | PUFA supplementation or not | 17 | 1074/3614 | OR | 0.67 (0.49 to 0.90) | 0.008 | Yes | 62.14 | No | Yes | No | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Liu 2014 | Low dose glucocrorticoids | Low dose glucocrorticoids use or not | 5 | 285/843 | RR | 0.71 (0.55 to 0.92) | 0.008 | Yes | 31.82 | No | No | Yes | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Liu 2015 | Medium dose glucocrorticoids | Medium dose glucocrorticoids use or not | 19 | 1915/5968 | RR | 0.76 (0.60 to 0.96) | 0.020 | Yes | 49.57 | Yes | Yes | No | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Liu 2015 | Glucorticoids | Glucorticoids use or not | 27 | 2255/7019 | RR | 0.77 (0.66 to 0.90) | 0.001 | Yes | 40.08 | Yes | Yes | No | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Khan 2020 | TAVR in patients with aortic stenosis with low risk | TAVR or SAVR | 3 | 563/2633 | OR | 0.13 (0.09 to 0.18) | 0.0000 | Yes | 48.84 | No | No | Yes | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Khan 2020 | TAVR in patients with aortic stenosis with intermediate risk | TAVR or SAVR | 2 | 812/3692 | OR | 0.23 (0.16 to 0.33) | 0.0000 | NP | 76.17 | NP | No | Yes | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Khan 2020 | TAVR in patients with low and intermediate risk | TAVR or SAVR | 4 | 1375/6325 | OR | 0.17 (0.12 to 0.24) | 0.0000 | No | 82.84 | Yes | No | Yes | >25% | Moderate | High |

| Chatterjee 2013 | Oral amiodarone | Oral amiodarone or not | 8 | 472/1906 | RR | 0.58 (0.47 to 0.72) | 0.0000 | No | 36.28 | No | No | Yes | ≤25% | Low | Low |

| Chatterjee 2013 | IV amiodarone | IV amiodarone or not | 15 | 598/2044 | RR | 0.57 (0.43 to 0.75) | 0.0001 | Yes | 68.26 | Yes | Yes | Yes | ≤25% | Low | Low |

| Chatterjee 2013 | Preoperative amiodarone | Preoperative amiodarone or not | 11 | 585/2231 | RR | 0.55 (0.46 to 0.64) | 0.0000 | No | 18.49 | No | No | Yes | ≤25% | Low | Low |

| Chatterjee 2013 | Peri/postoperative amiodarone p | Peri/postoperative amiodarone or not | 12 | 482/1717 | RR | 0.55 (0.38 to 0.80) | 0.001 | Yes | 57.85 | Yes | Yes | Yes | ≤25% | Low | Low |

| Miller 2005 | Magnesium | Magnesium administration or not | 20 | 577/2490 | OR | 0.53 (0.38 to 0.74) | 0.0002 | Yes | 59.67 | Yes | Yes | No | >25% | Low | Critically low |

| Wiesbauer 2007 | B-blockers | B-blockers use or not | 26 | 1019/3959 | OR | 0.38 (0.29 to 0.49) | 0.0000 | No | 45.04 | Yes | Yes | Yes | >25% | Low | Critically low |

| Violi 2014 | Antioxidants | Antioxidants use or not | 15 | 481/1738 | RR | 0.58 (0.45 to 0.76) | 0.0001 | Yes | 54.39 | Yes | Yes | No | >25% | Low | Critically low |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CE, class of evidence; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; ES, effect size; ESB, excess significance bias; GLE, GRADE level of evidence; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; I2, heterogeneity; K, number of studies for each factor; LS, largest study with significant effect; n, number of cases; N, total number of cohort per factor; NA, not assessable; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; NP, not pertinent, because the number of observed studies is less than the expected; NR, not reported; OSAS, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; PI, prediction interval; PUFAs, polyunsaturated fatty acids; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RoB, risk of bias; RR, risk ratio; SAVR, surgical aorta valve replacement; SSE, small study effects; TAVR, transcatheter aorta valve replacement; vit, vitamin.

Overall, 30 of the 48 (63%) associations reported a nominally significant summary result at p<0.05 (19 had p≤0.001). Twenty-one (44%) did not show considerable heterogeneity (I2<50%), and only seven associations (15%) had a 95% prediction interval that excluded the null value. Nineteen (40%) showed small study effects, and 21 (44%) showed excess significance bias. The ES of the largest study had a nominally statistically significant effect (p≤0.05) in 19 (40%) associations.

The quality of included meta-analyses of RCTs was scored as high in 20, moderate in 5 and low or critically low in 9 (online supplemental appendix 5).

By applying the credibility criteria for meta-analyses of RCTs, three (6%) associations between protective factors and POAF presented a high GLE (tables 2 and 3; online supplemental etable 1, appendix 5): atrial or biatrial pacing and the performance of a posterior pericardiotomy. Twenty associations (42%) of protective factors and the risk for POAF presented a moderate GLE, for instance, the use of amiodarone, beta-blockers, colchicine and glucocorticoid as well as TAVR as compared with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) (tables 2 and 3; online supplemental etable 1, appendix 5). The remaining seven (14%) statistically significant associations between protective factors and POAF presented low GLE, while 18 associations (38%) were not statistically significant (table 2; Online supplemental etable 1, appendices 5 and 6).

Table 3.

Summary of associations with high epidemiological credibility of risk and protective factors with the risk of postoperative atrial fibrillation

| Level of credibility | Associations |

| Meta-analyses including Observational studies | |

| Convincing | Transfemoral transcatheter AVR |

| High suggestive | Preoperative hypertension, high neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio |

| Grade level of evidence | |

| Meta-analyses including RCTs | |

| High | Atrial pacing, biatrial pacing, posterior pericardiotomy |

| Medium | Dexmedetomidine, glucocorticoids (general, low, medium doses), hydrocortisone, ranolazine, statin (pre-treatment and perioperative), antioxidant, PUFAs (alone or in combinations with Vitamin C and E), amiodarone, colchicine, TAVR compared with SAVR, landiolol, carvedilol, prophylactic NAC use |

AVR, aortic valve replacement; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; PUFAs, polyunsaturated fatty acids; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SAVR, surgical aorta valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aorta valve replacement.

Discussion

This study reviewed 47 meta-analyses of observational and randomised design and found 40 significant associations of preoperative and postoperative risk and protective factors for POAF. Few of these were supported by convincing evidence or high GLE evidence, namely, the transfemoral TAVR versus non-transfemoral approach, the use of atrial or biatrial pacing and the choice of posterior pericardiotomy.

This study is the first umbrella review that systematically assesses the potential risk and protective factor associated with POAF across broad spectrum of meta-analyses of observational and randomised studies and grade the evidence by using well-established criteria of credibility.19 25 26 Umbrella review methods have been previously used to assess the associations between other adverse health conditions with potential risk and protective factors, such as AF,13 adiposity27 and vitamin D concentration.26 This method is appropriate for a research area that is undoubtedly complex and ambiguous.3 6 The large number of included patients (more than 400 000) in combination with the high number of cases per association enabled robust classifications. Furthermore, the AMSTAR 2 tool for quality assessment of the included meta-analyses allowed for a confident interpretation of our results. Hence, our proposed grading needs to be considered when planning future studies on preventive models of POAF.

POAF is a common complication after repair of severe aortic stenosis.28 Data from a meta-analysis of observational studies29 showed that non-transfemoral TAVR versus transfemoral TAVR increases the risk of POAF threefold, a finding supported by convincing evidence. Contrary to the transfemoral approach, patients undergoing transapical TAVR require a pericardiotomy and several studies have shown that pericardial injury can lead to postoperative inflammation and the subsequent development of POAF. Furthermore, meta-analyses of RCTs30 for patients at low and intermediate surgical risk showed a significant risk reduction for POAF using TAVR compared with SAVR. This finding is to be expected since an open procedure is associated with more postoperative inflammation, enhanced sympathetic stimulation and oxidative stress as opposed to a minimally invasive procedure such as TAVR.28 31

One of the modifiable preoperative factors associated with POAF, supported by highly convincing evidence, was hypertension.32 Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for AF,33 and its adequate management during the preoperative period may protect against POAF by reducing both high left ventricular filling pressures and easing atrial stretch.32–34

In our study, the most critical perioperative protective factors for POAF prevention, that did not involve medical therapy, were atrial or biatrial pacing and posterior pericardiotomy, both supported by high GLE.35 Overdrive atrial pacing might prevent POAF by reducing the risk of bradycardia and bradycardia-mediated atrial ectopic beats.3 In the meta-analysis by Ruan et al,35 the reduction in POAF risk with moderate heterogeneity and high quality according to AMSTAR 2 was meaningful. Posterior pericardiotomy is a risk-reducing procedure for postoperative pericarditis by making an incision in the posterior pericardium and connecting the pericardial to the left pleural space.3 We found that about two-thirds as many patients undergoing cardiac surgery were protected from POAF when posterior pericardiotomy was used compared with not, at the expense of more pleural effusions.36

More than 10 pharmacological treatments have been studied as preventive treatment options against POAF. Drugs provided statistically significant prevention of POAF in meta-analyses of RCTs with at least moderate GLE included amiodarone,37 statins,38 colchicine,39 b-blockers (carvedilol and landiolol)40 41 and glucocorticoids.42 Amiodarone and b-blockers are established treatments for AF and POAF, recommended in the current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines (Class I, level of evidence A),33 a recommendation supported by our results. However, the use of statins, colchicine and glucocorticoids can also be considered, even if they are not directly recommended by the current ESC guidelines.33 Due to their anti-inflammatory actions,3 these medications may play a protective role against POAF in the preoperative management of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, as shown by our results based on meta-analyses of RCTs, supported by a moderate level of evidence.

Furthermore, ranolasine appears to have a protective role against POAF. However, the results are based on meta-analysis with few events.43 Controversial results have also been shown for the effects of fish oils44 45 and antioxidants46 47 and should not be broadly recommended before cardiac surgery, according to our analysis.

In this study, we described the broad picture of risk and protective factors that have been studied for POAF. However, our study has several limitations that should be reported. First, asymmetry and excess significance tests offer bias clues but not definitive proof. Second, even we appraised the quality of the included meta-analyses, we did not assess the quality of their off-studies. Component studies should be qualitatively assessed in the original meta-analyses. Third, although we evaluated many risks and protective factors, there might be other factors of POAF that have not yet been evaluated in published meta-analyses, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe heart failure. Fourth, the associations supported by convincing or highly suggestive evidence based on observational data can be considered strong but are not evidence of causality. Fifth, the grading criteria applied in the credibility assessment are not validated in empirical studies. However, they are proposed by expert panels of well-renowned epidemiologists.25 48

Conclusions

Although POAF is a common complication after cardiac surgery and has been thoroughly studied over the last decades, only 6 of the 61 (9.8%) associations reported here were supported by high-level evidence. While some associations might be genuine, there is still a degree of uncertainty. In our study, we were able to confirm the protective role of TAVR versus non-TAVR or SAVR, along with the protective role of amiodarone, B-blockers, atrial pacing and posterior pericardiotomy against POAF, and the risk of untreated hypertension. In addition, our analysis suggests that statins, glucocorticoids and colchicine may play a role in preventing POAF. Further investigation by meta-analyses of individual participant data may facilitate the study of sources of between-study heterogeneity and identify risk and protective factors of POAF in specific subpopulations.49

Footnotes

Contributors: EC, DT and ED designed the study. MS and DK performed a comprehensive screening of the literature, selected the studies included in the meta-analysis and abstracted the data items. ED and DT performed the statistical analysis. EC drafted the manuscript and is the guarantor of the paper. EC, ED, DT, MS, DK, LOK, FV, EIC, JA, EF, CA, CT, and HW interpreted the results and edited the manuscript critically. All the co-authors have read and accepted this version of the manuscript.

Funding: Emmanouil Charitakis has received funding from ALF grants (County Council of Östergötland) RÖ818141.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Lubitz SA, Yin X, Rienstra M, et al. Long-term outcomes of secondary atrial fibrillation in the community: the Framingham heart study. Circulation 2015;131:1648–55. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jørgensen TH, Thyregod HGH, Tarp JB, et al. Temporal changes of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients randomized to surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Int J Cardiol 2017;234:16–21. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobrev D, Aguilar M, Heijman J, et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: mechanisms, manifestations and management. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019;16:417–36. 10.1038/s41569-019-0166-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funk M, Richards SB, Desjardins J, et al. Incidence, timing, symptoms, and risk factors for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Am J Crit Care 2003;12:424–33. 10.4037/ajcc2003.12.5.424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathew JP, Fontes ML, Tudor IC, et al. A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. JAMA 2004;291:1720–9. 10.1001/jama.291.14.1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg JW, Lancaster TS, Schuessler RB, et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery: a persistent complication. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;52:665–72. 10.1093/ejcts/ezx039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aranki SF, Shaw DP, Adams DH, et al. Predictors of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery surgery. current trends and impact on hospital resources. Circulation 1996;94:390–7. 10.1161/01.cir.94.3.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruins P, te Velthuis H, Yazdanbakhsh AP, et al. Activation of the complement system during and after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: postsurgery activation involves C-reactive protein and is associated with postoperative arrhythmia. Circulation 1997;96:3542–8. 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hak Łukasz, Myśliwska J, Wieckiewicz J, et al. Interleukin-2 as a predictor of early postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiopulmonary bypass graft (CABG). J Interferon Cytokine Res 2009;29:327–32. 10.1089/jir.2008.0082.2906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shantsila E, Watson T, Lip GYH. Atrial fibrillation post-cardiac surgery: changing perspectives. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1437–41. 10.1185/030079906X115658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ioannidis JPA. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ 2009;181:488–93. 10.1503/cmaj.081086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellou V, Belbasis L, Tzoulaki I, et al. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson's disease: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;23:1–9. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belbasis L, Mavrogiannis MC, Emfietzoglou M, et al. Environmental factors, serum biomarkers and risk of atrial fibrillation: an exposure-wide umbrella review of meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2020;35:223–39. 10.1007/s10654-020-00618-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ioannidis J. Next-generation systematic reviews: prospective meta-analysis, individual-level data, networks and umbrella reviews. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1456–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (moose) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raglan O, Kalliala I, Markozannes G, et al. Risk factors for endometrial cancer: an umbrella review of the literature. Int J Cancer 2019;145:1719–30. 10.1002/ijc.31961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dragioti E, Solmi M, Favaro A, et al. Association of antidepressant use with adverse health outcomes: a systematic umbrella review. JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76:1241–55. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ioannidis JPA, Trikalinos TA. An exploratory test for an excess of significant findings. Clin Trials 2007;4:245–53. 10.1177/1740774507079441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schünemann HBJ, Guyatt G, Oxman A. Grade Handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations, 2013. Available: https://gradepro.org/

- 25.Pollock A, Farmer SE, Brady MC, et al. An algorithm was developed to assign GRADE levels of evidence to comparisons within systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;70:106–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theodoratou E, Tzoulaki I, Zgaga L, et al. Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. BMJ 2014;348:g2035. 10.1136/bmj.g2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim MS, Kim WJ, Khera AV, et al. Association between adiposity and cardiovascular outcomes: an umbrella review and meta-analysis of observational and Mendelian randomization studies. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3388–403. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahim B, Malaisrie SC, George I, et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation or flutter following transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement: partner 3 trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:1565–74. 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angsubhakorn N, Kittipibul V, Prasitlumkum N, et al. Non-transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement approach is associated with a higher risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung Circ 2020;29:748–58. 10.1016/j.hlc.2019.06.716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan MR, Kayani WT, Manan M, et al. Comparison of surgical versus transcatheter aortic valve replacement for patients with aortic stenosis at low-intermediate risk. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2020;10:135–44. 10.21037/cdt.2020.02.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maesen B, Nijs J, Maessen J, et al. Post-operative atrial fibrillation: a maze of mechanisms. Europace 2012;14:159–74. 10.1093/europace/eur208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou A-G, Wang X-X, Pan D-B, et al. Preoperative antihypertensive medication in relation to postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2017;2017:1–12. 10.1155/2017/1203538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European association of Cardio-Thoracic surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Gattobigio R, et al. Impact of blood pressure variability on cardiac and cerebrovascular complications in hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2007;20:154–61. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruan Y, Robinson NB, Naik A, et al. Effect of atrial pacing on post-operative atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass grafting: pairwise and network meta-analyses. Int J Cardiol 2020;302:103–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu X-L, Chen Y, Zhou Z-D, et al. Posterior pericardiotomy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Cardiol 2016;215:252–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillespie EL, Coleman CI, Sander S, et al. Effect of prophylactic amiodarone on clinical and economic outcomes after cardiothoracic surgery: a meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother 2005;39:1409–15. 10.1345/aph.1E592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patti G, Bennett R, Seshasai SRK, et al. Statin pretreatment and risk of in-hospital atrial fibrillation among patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a collaborative meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials. Europace 2015;17:855–63. 10.1093/europace/euv001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lennerz C, Barman M, Tantawy M, et al. Colchicine for primary prevention of atrial fibrillation after open-heart surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2017;249:127–37. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DiNicolantonio JJ, Beavers CJ, Menezes AR, et al. Meta-analysis comparing carvedilol versus metoprolol for the prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:565–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li L, Ai Q, Lin L, et al. Efficacy and safety of landiolol for prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:10265–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu C, Wang J, Yiu D, et al. The efficacy of glucocorticoids for the prevention of atrial fibrillation, or length of intensive care unite or hospital stay after cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Ther 2014;32:89–96. 10.1111/1755-5922.12062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guerra F, Romandini A, Barbarossa A, et al. Ranolazine for rhythm control in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2017;227:284–91. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo X-Y, Yan X-L, Chen Y-W, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for postoperative atrial fibrillation: alone or in combination with antioxidant vitamins? Heart Lung Circ 2014;23:743–50. 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu T, Korantzopoulos P, Shehata M, et al. Prevention of atrial fibrillation with omega-3 fatty acids: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Heart 2011;97:1034–40. 10.1136/hrt.2010.215350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Violi F, Pastori D, Pignatelli P, et al. Antioxidants for prevention of atrial fibrillation: a potentially useful future therapeutic approach? A review of the literature and meta-analysis. Europace 2014;16:1107–16. 10.1093/europace/euu040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hemilä H, Suonsyrjä T. Vitamin C for preventing atrial fibrillation in high risk patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2017;17:49. 10.1186/s12872-017-0478-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ioannidis JPA, Boffetta P, Little J, et al. Assessment of cumulative evidence on genetic associations: interim guidelines. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:120–32. 10.1093/ije/dym159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ 2010;340:c221. 10.1136/bmj.c221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2022-002074supp001.pdf (285.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.