Abstract

Objective

To investigate effective, quality-adjusted, coverage and inequality of maternal and child health (MCH) services to assess progress in improving quality of care in Cambodia.

Design

A retrospective secondary analysis using the three most recent (2005, 2010 and 2014) Demographic and Health Surveys.

Setting

Cambodia.

Participants

53 155 women aged 15–49 years old and 23 242 children under 5 years old across the three surveys.

Outcome measures

We estimated crude coverage, effective coverage and inequality in effective coverage for five MCH services over time: antenatal care (ANC), facility delivery and sick childcare for diarrhoea, pneumonia and fever. Quality was defined by the proportion of care seekers who received a set of interventions during healthcare visits. Effective coverage was estimated by combining crude coverage and quality. We used equiplots and risk ratios, to assess patterns in inequality in MCH effective coverage across wealth quintile, urban–rural and women’s education levels and over time.

Results

In 2014, crude and effective coverage was 80.1% and 56.4%, respectively, for maternal health services (ANC and facility delivery) and 59.1% and 26.9%, respectively, for sick childcare (diarrhoea, pneumonia and fever). Between 2005 and 2014, effective coverage improved for all services, but improvements were larger for maternal healthcare than for sick child care. In 2014, poorer children were more likely to receive oral rehydration solution for diarrhoea than children from richer households. Meanwhile, women from urban areas were more likely to receive a postnatal check before getting discharged.

Conclusions

Effective coverage has generally improved in Cambodia but efforts remain to improve quality for all MCH services. Our results point to substantial gaps in curative sick child care, a large share of which is provided by unregulated private providers in Cambodia. Policymakers should focus on improving effective coverage, and not only crude coverage, to achieve the health-related Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

Keywords: Health policy, Quality in health care, International health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study included nationally representative population data to estimate effective, quality-adjusted, coverage and inequality of maternal and child health services.

This study used three waves (2005, 2010 and 2014) of surveys to observe the temporal changes in coverage, quality and inequality.

The study is limited by the type of measures included in the Demographic and Health Surveys to assess quality.

Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 aims to achieve universal health coverage (UHC), by ensuring access to quality essential health services by 2030.1 Despite substantial improvement in access to healthcare services, quality of care remains poor and variable across low and middle-income countries (LMICs).2–5 The Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems in the SDG era (ie, the HQSS Commission) estimated that high-quality health systems could save one million newborn deaths annually.4 Vulnerable groups, including the poor and the less educated, tend to receive worst quality of care.5–7 Thus, quality improvement needs to be a central pillar of UHC.

An increasing body of evidence recommends a shift from tracking ‘crude’ or ‘contact’ coverage to ‘effective’ coverage,5–9 defined as the proportion of a population in need of a service that resulted in a positive health outcome from the service.10 Recent literature have shown a gap between crude and effective coverage ranged from 40% to 60% in LMICs.7 11 12 This indicates that many patients who come in contact with the health system are not treated according to standards of care.

Cambodia is a lower middle-income country located in Southeast Asia with a population of 16.72 million people.13 Since the late 1990s, the country has experienced consistent economic growth and a reduction in poverty rates.14 In the past decades, the Cambodian government has focused on increasing utilisation of maternal and child health (MCH) services. From 2000 to 2014, Cambodia reduced its under-5 mortality rate from 124 to 35 per 1000 live births and the maternal morality ratio from 437 to 170 per 100 000 live births.15 Increased in facility deliveries and child vaccination programmes have substantially reduced these maternal and child deaths during the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) era.16 17

However, in order to achieve the health-related SDGs by 2030, maternal mortality must be reduced by an additional 60% and under-5 mortality by an additional 30%. Using Global Burden of Disease data in 2016, Kruk et al found that deaths due to poor quality care were two times as high as deaths due to non-utilisation of healthcare services in Cambodia.18 Moreover, inequality in accessing maternal and child care services across geographic locations, urban–rural residents and wealth quintile was observed in Cambodia.19 20 To avert these additional maternal and child deaths, a high-quality equitable healthcare services is needed. The first step is to monitor progress during the MDG era.

To our knowledge, no study has assessed the effective, quality-adjusted, coverage of MCH services in Cambodia. Previous research has mostly focused on the utilisation of MCH services.21–23 Thus, this study estimates the effective coverage of five MCH services and inequality in effective coverage using data from 2005 to 2014.

Methods

Data sources

This is a secondary statistical analysis using data from the Cambodia Demographic and Health Surveys (CDHS) to examine changes in crude coverage, effective coverage and inequality in effective coverage of MCH services over time. The three most recent waves—2005, 2010 and 2014—of the CDHS were included. The CDHS is a nationally representative, population-based, cross-sectional survey carried out every 4–5 years.15 Our population of interest (N) included all women of reproductive age (15–49 years old) who had at least one live birth in the past 5 years preceding each survey wave for maternal care, and all children under 5 years old living in residential households for sick childcare visits. The CDHS collects data on a wide range of health services, including across the MCH continuum of care. Sampling strategies and methodology have been described elsewhere.24

Measures

Crude coverage

Crude coverage was calculated by the proportion of women or children who needed healthcare (due to true or perceived needs) and who sought care at health facilities. We estimated crude coverage for five MCH services: antenatal care (ANC), delivery and care for diarrhoea, pneumonia and fever. ANC was defined as the proportion of women with at least one live birth in the 5 years preceding the survey who reported at least four ANC visits for their most recent birth. Delivery care was defined as the proportion of women who gave birth in the 5 years preceding the survey and who delivered at a health facility, including all public and private facilities (excluding those who gave birth at home and undefined locations).

Care for diarrhoea, pneumonia and fever was defined, respectively, as the proportion of children who had diarrhoea, symptoms of pneumonia (a cough accompanied by short, rapid breathing and difficulty breathing as a result of a problem in the chest), or fever, in the 2 weeks preceding the survey for whom advice or treatment was sought from a health facility, including all public and private facilities except pharmacies and traditional healers.

Effective coverage

Based on the calculation used by Arsenault et al7 and Hategeka et al,6 we estimated effective coverage as:

where EC is effective coverage, Q is quality of MCH services, U is utilisation of MCH services and N is need for MCH services. Since the CDHS had only a few indicators to estimate the quality of services, the effective coverage estimates reported in this study should be considered an upper limit of the quality of MCH services.

Quality of care was defined based on four reports: the HQSS Commission’s framework,4 the WHO recommendations on ANC for a positive pregnancy experience,25 the National Strategy for Reproductive and Sexual Health of Cambodia 2017–202026 and the WHO standards for improving the quality of care for children and young adolescents in health facilities.27

Quality-adjusted ANC was estimated by the proportion of women who received at least four ANC visits and reported receiving five basic services at any point during ANC: their blood pressure was measured, a urine and a blood sample were collected, they were given or bought iron tablets or syrup, and they were counselled on potential complications to look out for during pregnancy. Quality-adjusted delivery care was defined as the proportion of women who delivered at a health facility and who reported that someone examined them or asked questions about their health before being discharged. Quality-adjusted care for diarrhoea was defined as the proportion of children who sought care at a health facility for diarrhoea and who received oral rehydration solution (ORS) from a special packet, prepackaged or from a homemade fluid. Quality-adjusted care for pneumonia was defined as the proportion of children who visited a health facility for suspected pneumonia and who received antibiotics (pills, syrup or injection). Quality-adjusted care for fever was defined as children who sought care at a health facility and received a blood test for suspected malaria. Detailed indicator definitions are shown in online supplemental table 1.

bmjopen-2022-062028supp001.pdf (88.2KB, pdf)

Inequality in effective coverage of MCH services

Inequalities in effective coverage of five MCH services were assessed using three measures of socioeconomic position: household wealth quintile, area of residence (urban vs rural) and the woman’s education level as provided by the CDHS.15 The wealth index, provided by the CDHS, is calculated based on a household’s ownership of selected assets, such as televisions and bicycles; housing construction materials and types of water access and sanitation facilities.28 The wealth index is divided into five quintiles (lowest—Q1, second—Q2, middle—Q3, fourth—Q4 and highest—Q5) based on a continuous scale of relative wealth in the country.28 Details on the calculation of the wealth index can be found elsewhere.29 The women’s education was combined into three levels (no education, primary school only and secondary or higher education).

Statistical analysis

We first used descriptive statistics to estimate crude coverage and effective coverage for the five MCH services in 2005, 2010 and 2014. Data for child pneumonia care were not available in 2005. Line graphs were used to present the trends in national averages over time for each health service. Second, we assessed inequalities in effective coverage visually using equiplots across wealth quintiles, maternal education and area of residence (urban vs rural). Finally, we used risk ratios (RRs), to compare effective coverage in 2014 between the top and bottom categories of each measure of socioeconomic position (wealth quintiles, education and urban residence). We used logistic regressions to model the log odds of effective coverage and transformed the coefficients into marginal predicted risks using postestimation commands to calculate the RR. We used the logistic, margins and nlcom commands in STATA V.16.0.30 Statistical code for RR calculation is publicly available on a GitHub repository: https://github.com/mkkim1/RiskRatio_Cambodia.git.

Two additional subanalyses were conducted. First, we estimated the crude and effective coverage in 2000 to observe the trend in the last two decades. However, due to the age of the data, we excluded the 2000 data from the main analysis (online supplemental table 2). Indicators to estimate effective coverage for facility delivery and sick childcare for fever were not available in 2000. Second, we used postpartum check-up after discharge to estimate effective coverage for childbirth and compare with the results from the main analysis (online supplemental table 3, figure 1).

All analyses, including logistic regressions, were adjusted for the survey design (clustering, stratification and survey weights) except the equiplots due to a limitation of the statistical software package. Stata SE V.16.0 was used for all analyses.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without public involvement. Public were not consuted and invited to comment on the study design and analysis.

Results

Description of the study population

A total of 53 155 women of reproductive age (15–49 years old) were included across the three survey waves. The proportion of women who gave birth within the 5 years preceding the survey slightly decreased from 34.9% in 2005 to 34.0% in 2014. Most women lived in rural areas and completed primary education (table 1). In total, 23 242 children under 5 years were included. Fever was the most prevalent child illness, with 27.1% of children suffering from fever in the 2 weeks prior to the survey in 2014 (table 1). High prevalence of fever could be explained by the high burden of malaria along the national borders, including in the western provinces of Battambang and Pailin.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample in Cambodia from 2005 to 2014

| Survey, year | 2005 N (%) | 2010 N (%) | 2014 N (%) |

| Number of households | 14 243 | 15 667 | 15 825 |

| Women (age 15–49) | 16 823 | 18 754 | 17 578 |

| Women who gave birth within 5 years of the survey | 5865 (34.9%) | 6472 (34.5%) | 5973 (34.0%) |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 2973 (17.7%) | 3936 (21.0%) | 3251 (18.5%) |

| Rural | 13 851 (82.3%) | 14 819 (79.0%) | 14 328 (81.5%) |

| Education | |||

| No education | 3270 (19.4%) | 2974 (15.9%) | 2251 (12.8%) |

| Primary | 9389 (55.8%) | 9265 (49.4%) | 8281 (47.1%) |

| Secondary and higher | 4165 (24.8%) | 6516 (34.7%) | 7047 (40.1%) |

| Wealth quintile | |||

| Lowest | 3018 (17.9%) | 3389 (18.1%) | 3144 (17.9%) |

| Second | 3165 (18.8%) | 3517 (18.7%) | 3314 (18.9%) |

| Middle | 3246 (19.3%) | 3595 (19.2%) | 3381 (19.2%) |

| Fourth | 3308 (19.7%) | 3827 (20.4%) | 3613 (20.6%) |

| Highest | 4089 (24.3%) | 4429 (23.6%) | 4128 (23.5%) |

| Maternal healthcare | |||

| Crude coverage of antenatal care and facility delivery (mean, range) | 25.1% (23.2%–27.0%) | 58.1% (56.8%–59.4%) | 80.1% (75.6%–84.6%) |

| Effective coverage of antenatal care and facility delivery (mean, range) | 12.6% (4.7%–20.5%) | 33.6% (16.2%–51.1%) | 56.4% (32.8%–80.1%) |

| Children (age<5) | 7789 | 8200 | 7253 |

| Children who had diarrhoea 2 weeks prior to the survey | 1420 (18.2%) | 1161 (14.2%) | 902 (12.4%) |

| Children who had pneumonia 2 weeks prior to the survey | 2224 (28.6%) | 1741 (21.2%) | 1531 (21.1%) |

| Children who had fever 2 weeks prior to the survey | 2576 (33.1%) | 2194 (26.8%) | 1968 (27.1%) |

| Care for sick children | |||

| Crude coverage of diarrhoea, pneumonia, and fever (mean, range) | 45.3% (41.1%–47.8%) | 69.1% (58.9%–75.5%) | 59.1% (55.5%–61.3%) |

| Effective coverage of diarrhoea, pneumonia, and fever (mean, range)* | 11.7% (2.3%–21.1%) | 25.1% (10.3%–37.3%) | 29.6% (11.5%–51.5%) |

*Effective coverage for pneumonia in 2005 was not included due to missing data in CDHS.

CDHS, Cambodia Demographic and Health Surveys.

Overall crude and effective coverage

In 2014, average crude and effective coverage were 80.1% and 56.4%, respectively, for maternal healthcare (ANC and delivery), and 59.1% and 29.6% for sick child care (care for child diarrhoea, pneumonia and fever) (table 1). For maternal health, effective coverage was increased by 21.0% and 22.8% from 2005 to 2010 and 2010 to 2014, respectively (table 1). For sick childcare, effective coverage increased by 13.4% and 4.5% from 2005 to 2010 and 2010 to 2014, respectively (table 1). Estimates for crude and effective coverage for each indicator are found in online supplemental table 2. Delivery had the highest effective coverage at 80.1% in 2014 (online supplemental table 2). Meanwhile, effective coverage for fever had the lowest effective coverage at 2.3% in 2005 (online supplemental table 2).

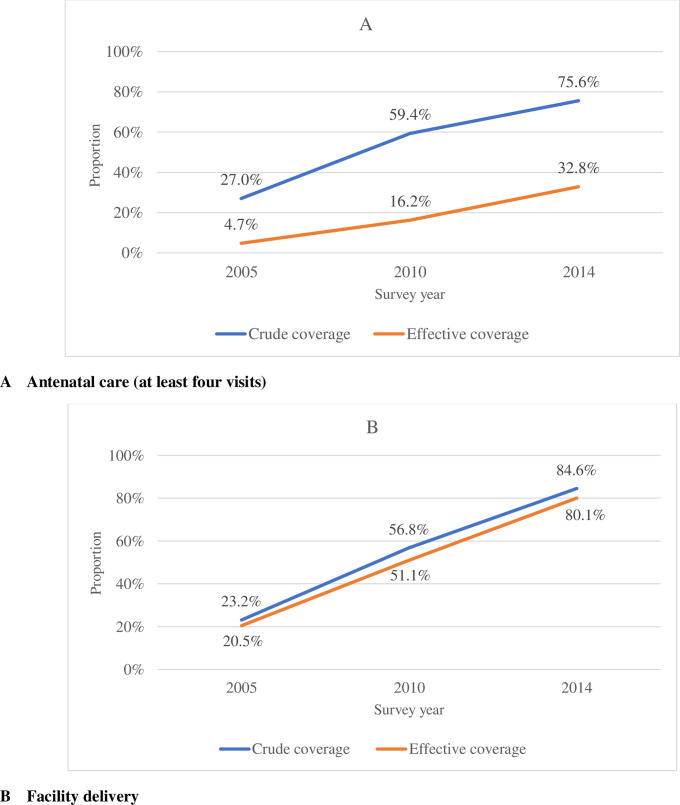

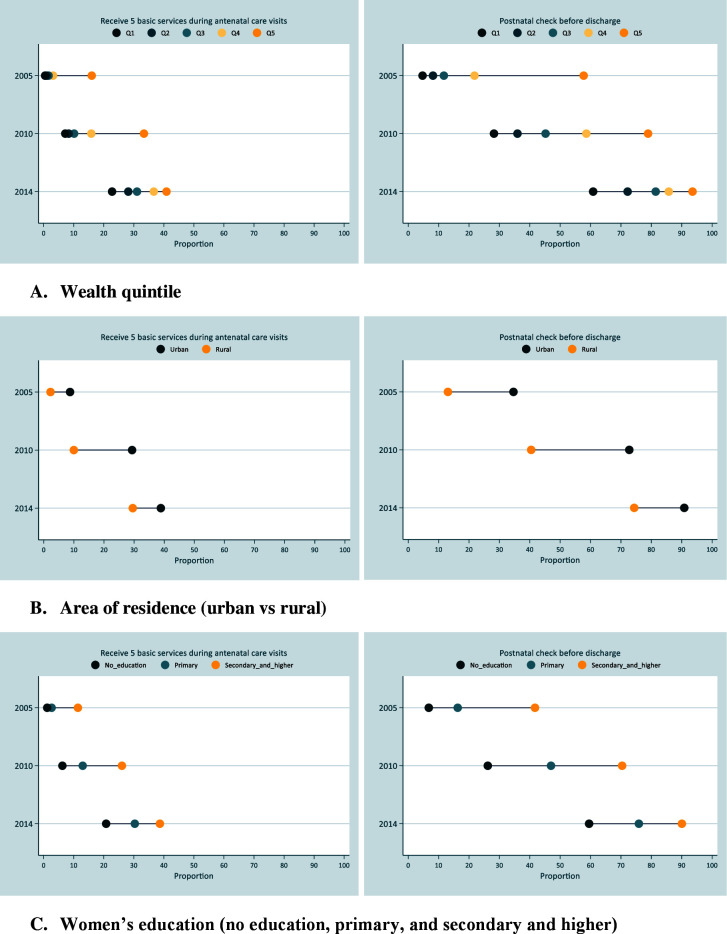

Maternal healthcare

Figure 1 shows a continuous increase in crude and effective coverage for ANC and facility delivery from 2005 to 2014. In 2014, 80.1% of women who delivered at a facility had a postnatal check before being discharged and around half of women who had four ANC visits received the five basic services during their pregnancy. Effective coverage in maternal healthcare services improved even among the poorest. For example, in 2005, only 4.7% of women in the lowest wealth quintile received a postnatal check, while this increased to 60.9% in 2014 (figure 2). The proportion of women from rural areas who received the five basic services during ANC increased by 13-folds from 2005 to 2014, from 2.2% to 29.6% (figure 2). Inequalities also appeared to be reduced according to the equiplots. However, socioeconomic inequalities in effective coverage remained in 2014. Women in the richest wealth quintile in Cambodia were 1.7 times more likely to receive all five services during ANC visits (RR=1.7, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.0) compared with the poorest and they were 1.4 times more likely to receive a postnatal check before discharge (RR=1.4, 95% CI 1.4 to 1.5) (table 2).

Figure 1.

Crude and effective coverage of maternal health care in Cambodia from 2005 to 2014. (A) at least 4 antenatal care (ANC) visits. (B) facility delivery. Effective coverage for antenatal care was estimated by the proportion of womwen who received at least four ANC visits and reported receiving five basic services at any point during ANC; their blood pressure was measured, a urine and a blood sample was collected, they were give or bough iron tablets, or syrup, and they were counseled on potential complications to look out for during pregnancy. Effective coverage for facility delivery was defined as the proportion of women who delivered at a healthy facility and who reported that someone examined them or asked questions about their health before being discharged.

Figure 2.

Equity in effective coverage of maternal health in Cambodia from 2005 to 2014 across (1) wealth quintile (2) area of residence (urban vs rural) (3) women's education (no education, primary and secondary and higher).

Table 2.

Risk ratios in effective coverage of five maternal and child health services between richest and poorest, least and most educated and urban versus rural residents, Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey 2014

| Indicators | Wealth quintile (Q5 vs Q1) | Urban–rural area | Women’s education levels (secondary or higher education vs no education) | |||

| RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | |

| Received five basic services during ANC visits | 1.7* | (1.5 to 2.0) | 1.5* | (1.3 to 1.6) | 1.9* | (1.6 to 2.2) |

| Postnatal check before discharge | 1.4* | (1.4 to 1.5) | 1.2* | (1.2 to 1.2) | 1.4* | (1.3 to 1.5) |

| Oral solution received for diarrhoea | 0.6† | (0.4 to 0.9) | 0.8 | (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.5‡ | (0.3 to 0.8) |

| Antibiotics received for pneumonia | 0.9 | (0.8 to 1.1) | 0.8* | (0.7 to 0.9) | 1.0 | (0.8 to 1.2) |

| Blood tested for malaria | 0.8 | (0.5 to 1.1) | 0.8 | (0.6 to 1.2) | 1.3 | (0.8 to 2.0) |

The RR is the ratio in effective coverage between top and bottom sub-groups: socioeconomic status—wealthiest quintile versus poorest quintile; urban and rural areas; and secondary or higher education versus no education. RR>1 indicates pro-rich distribution (higher effective coverage in the top group); RR<1 indicates pro-poor distribution (higher effective coverage in the lower sub-groups; RR=1 suggest an equal distribution in the effective coverage indicator.

*p<0.001.

†p<0.05.

‡p<0.01.

RR, risk ratio.

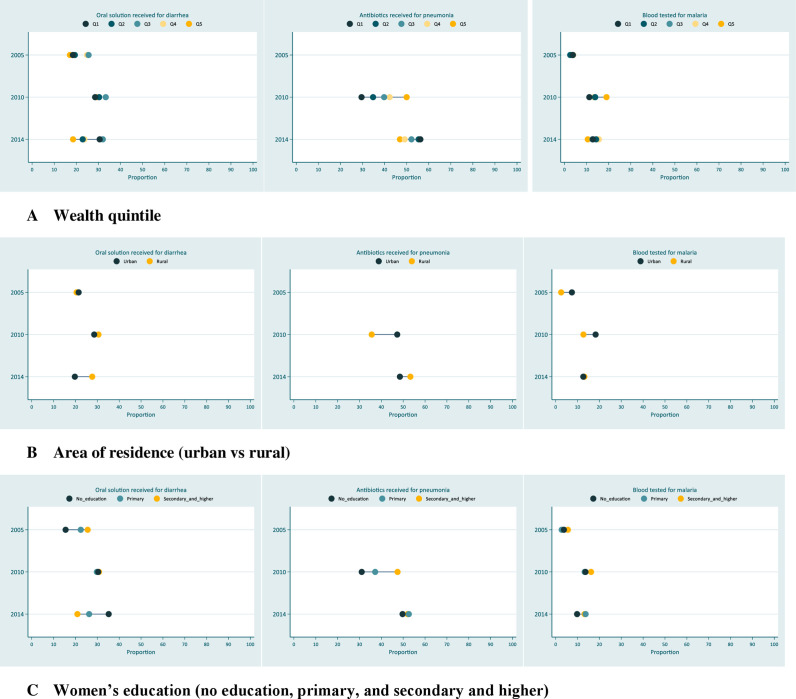

Sick child care

Figure 3 shows the trend in crude and effective coverage for sick child care. Overall, crude and effective coverage for sick child care did not improve as much as for maternal care between 2005 and 2014. The proportion of children with diarrhoea who received ORS and the proportion with fever who received a malaria test remained almost the same between 2010 and 2014 (figure 3). The proportion of children who received ORS for diarrhoea was higher in the poorest groups.

Figure 3.

Crude and effective coverage of care for child health in Cambodia from 2005 to 2014. (A) diarrhea (B) pneumonia (C) fever. Data for effective of pneumonia in 2005 were missing. Effective coverage for diarrhea was defined as the proportion of children who sought care at a health facility for diarrhea and who received oral rehydration therapy (ORT) from a special packet, pre-packaged or from a homemade fluid. Effective coverage for pneumonia was defined as the proportion of children who visited a health facility for pneumonia and who received antibiotics (pills, syrup, or injuction). Effective coverage for fever was defined as children who sought care at health facility and received a blood test for suspected malaria.

In 2014, children in the richest quintile were 0.6 times less likely to receive ORS when seeking care for diarrhoea (RR=0.6, 95% CI 0.4 to 0.9), compared with children from the poorest households (figure 4 and table 2). Similarly, children of most educated mothers were 0.5 times less likely to receive ORS for diarrhoea (RR=0.5, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.8) compared with those with no formal education (table 2).

Figure 4.

Equity in effective coverage of child health in Cambodia from 2005 to 2014 across (1) wealth quintile (2) area of residence (urban vs rural) (3) women's education (no education, primary, and secondary and higher). Data for effective coverage of pneumonia in 2005 were missing.

Discussion

In this study, we estimated crude coverage, effective coverage and inequality in effective coverage for five MCH services to assess progress in improving quality of healthcare in Cambodia from 2005 to 2014. We found that improvements in effective coverage were greater for maternal health services (ANC and facility delivery) than for curative services for sick children (diarrhoea, pneumonia and fever). Vulnerable women, including the poor, rural residents and less educated, experienced a greater improvement in effective coverage for facility delivery than ANC. Inequality gaps appeared to have been reversed for diarrhoea and pneumonia over time, where children from rural and poorer households received higher quality care than children from urban households.

Effective coverage in sick child care did not improve as much as for maternal health services. We also found a propoor distribution for sick child care—children from the poorest, less educated households and from rural areas, appeared to be more likely to receive ORS for diarrhoea and antibiotics for pneumonia, than children from richer, more educated households and urban areas. This could be because poorer children were relatively sicker but may also point to differences in quality between the types of providers used. Most curative care in Cambodia is delivered by an extensive network of loosely regulated private healthcare providers while the public sector is the predominant provider of preventive care and health promotion activities.14 31 According to the 2014 CDHS, 65% of care for child diarrhoea, fever or cough took place in the private sector.15 Private providers—mostly small practices, pharmacies or single-person practitioners—are also more prevalent in urban areas.14 The regulation of private providers in Cambodia remains a challenge where many operate without government accreditation.14 The Cambodia National Strategic Plan 2017–2020 revealed inadequate education of health professionals as an important impediment to improving the quality of health services.32 Since our results may point to large quality gaps in the private sector, the Cambodian government should regulate private healthcare providers for their curative clinical practice to ensure that patients receive quality care.

The increase in care seeking among poorer households could also have been influenced by the Health Equity Fund (HEF). The HEF, launched in 2000, is Cambodia’s largest financial protection scheme, covering the poorest one-fifth of the national population and aims to increase access to government health facilities.33 Since then, the utilisation of MCH services significantly increased among HEF-supported patients, particularly the facility deliveries.15 34 Yet, only one in two children received proper treatments at facilities. Only half of women received all five basic health services during their ANC visits.

From 2005 to 2014, the proportion of women who delivered at health facilities quadrupled. During the MDG era, several programmes have focused on improving maternal and newborn health including those led by the national government and international aid agencies, including the Korea Foundation for International Healthcare (KOFIH). Since 2013, KOFIH has implemented an integrated MCH programme to improve the quality of maternal and child healthcare services in the Battambang province by training healthcare workers—upgrading the skills of new midwives and training on partograph.35 The Government Midwifery Incentive Scheme started in 2006 aimed to increase the facility deliveries by paying midwives and other trained health personnel with cash incentives based on the number of live births they attend in public health facilities.36 These programmes may have been effective in improving both the utilisation and quality of delivery care. According to the 2014 CDHS report, 69% of deliveries took place in the public sector and 85.8% of births were attended by a midwife or a doctor.15 Nonetheless, we found a large gap in postpartum care before and after discharge which highlights missed opportunities for high-quality delivery care (online supplemental table 3 and figure 1). A meta-analysis found that receiving antenatal to postnatal care could reduce the risk of combined neonatal, perinatal and maternal mortality by 15%.37 The National Strategy for Reproductive and Sexual Health in 2017–2020 recommends four postnatal checks, one before and three after discharge.26 Despite these recommendations, mothers rarely return to the facilities after they get discharged. Inadequate transportation and long distances to health facilities might discourage women to return to the facilities after getting discharged. More outreach efforts like home visits, promotion of postnatal care during the antenatal period and at delivery are needed to ensure a continuum of delivery care for both mothers and newborns.

We found the largest difference (65.1%) between crude and effective coverage for children with fever in 2010. Effective coverage (blood test for suspected malaria) only improved by 1.1% from 2010 to 2014. This small increase in coverage might have resulted in a dramatic reduction in malaria-related deaths in Cambodia. In 2018, no malaria-related deaths were reported for the first time in the country’s history.38 The percentage of malaria cases significantly fell from 61% in 2015 to 27% in 2018.38 This promising improvement could have reduced the number of blood tests for suspected malaria cases.

Effective coverage lags behind crude coverage in Cambodia, indicating a need for improving the quality of MCH care. Similar or even lower levels of effective coverage have been found in other countries. Across 91 LMICs, effective coverage for ANC ranged from 53.8% on average in low-income countries to 93.3% in upper middle-income countries.7 In Rwanda, only 40.2% of women who gave birth in a facility in 2015 received a check-up before discharge while this estimate was almost the double (80.1%) in Cambodia.6 Quality-adjusted coverage for ANC (women who had at least 4 ANC visits and received at least 11 quality focuses intervention items) was about a half in Myanmar (14.6%) compared with Cambodia (32.8%).39 In Haiti, an average effective coverage for curative sick childcare, including taking history, testing and managing care, was 11.8% in 2013 while this estimate was almost tripled (29.7%) in Cambodia.11 Leslie et al found that effective coverage, providers’ adherence to evidence-based care guidelines, for sick childcare, was 37% in eight LMICs between 2007 and 2015.40 About 3 in 10 children received ORS in Vietnam (30.0%) and Cambodia (26.0%) in 2014.41

This study includes several limitations. First, the quality measures are not inclusive as they included only a limited number of recommended items that should be completed during MCH services. For instance, effective coverage for childbirth included only one item: check-up before discharge. Many other components of care are required for high-quality delivery care included a positive user experience (respectful, patient-centred delivery care) and high-quality intrapartum technical care. In addition, quality for sick child care was measured by whether the child received an appropriate treatment (ORS for diarrhoea, antibiotics for suspected pneumonia and blood test for suspected malaria), but the survey did not ask whether the healthcare providers explained the proper treatment instructions to the caregivers or conveyed their diagnosis. Given these limited measures, our quality estimates should be regarded as an upper bound of quality, a starting point for estimating quality-adjusted coverage rather than a definite estimate. Thus, better quality measures—user experience, competent care and timeliness of care—are needed. More studies need to go beyond utilisation of care and investigate health system quality.

Second, although we included the most recent CDHS surveys, our latest data points are from 2014. The CDHS announced an upcoming 2020–2021 survey.42 The Global Financing Facility estimated that service disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic could have the potential to leave 313 900 children without oral antibiotics for pneumonia and 77 600 women without access to facility deliveries.43 In Laos, antenatal care and postnatal care declined by an estimated 10% and 9%, respectively, immediately after the declaration of the pandemic.44 Future studies should estimate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on effective coverage in Cambodia.

Third, DHS data are self-reported by caregivers, which is subjected to recall bias. Women tend to report less accurately about care related to more complex diseases such as pneumonia,45 but they report better for more invasive procedures such as a blood test.46 To address reporting biases, other studies on quality of care have linked household surveys with facility assessments.47 In 2008, Cambodia implemented the Service Availability and Readiness Assessment, a national health facility assessment.48 Future studies should try to link different types of surveys to provide a more comprehensive picture of health system quality in Cambodia. Fourth, the findings are applicable only to the study country.

Conclusion

Despite the substantial improvement in maternal and child outcomes in the past decades in Cambodia, efforts are needed to improve quality of care. As Cambodia strives to meet the health-related SDGs by 2030, focusing on effective coverage will be important more than ever to address the residual maternal and child mortality. Additionally, inequalities across socioeconomic status need to be addressed to achieve equitable quality healthcare. Our study recommends policies to improve regulation and quality improvement efforts among the private sector where curative services for sick childcare are often provided. To our knowledge, this is the first study providing sound evidence of the quality of care in Cambodia over time. Health system strengthening efforts need to go beyond just improving the utilisation of care and start focusing on the content of care and patients’ experience. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the need for resilient, high-quality health systems more than ever. Thus, Cambodia needs to seize this moment to shift its attention and funding towards building a high-quality health system.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @mk_globalhealth

Contributors: MK and SAK are co-guarantors and co-led the overall process of publication. MK, SAK, CA were involved in the conceptualisation and interpretation of findings and helped draft the manuscript. MK and SAK conducted data analysis. JO and CEK helped draft the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Korea Foundation for International Healthcare. Award/Grant number: N/A

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are available upon request and available online from www.measuredhs.com.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This is a secondary data analysis of the Demographic Health Survey that is publicly available data. Thus, IRB approval is exempted. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.United Nations . The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2016 [Internet]. New York, 2016. Available: https://nacoesunidas.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/The_Sustainable_Development_Goals_Report_2016.pdf

- 2.Kruk ME, Chukwuma A, Mbaruku G, et al. Variation in quality of primary-care services in Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, Senegal, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:408–18. 10.2471/BLT.16.175869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruk ME, Leslie HH, Verguet S, et al. Quality of basic maternal care functions in health facilities of five African countries: an analysis of national health system surveys. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e845–55. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30180-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-Quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1196–252. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gage AD, Leslie HH, Bitton A, et al. Assessing the quality of primary care in Haiti. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:182–90. 10.2471/BLT.16.179846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hategeka C, Arsenault C, Kruk ME. Temporal trends in coverage, quality and equity of maternal and child health services in Rwanda, 2000–2015. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002768. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arsenault C, Jordan K, Lee D, et al. Equity in antenatal care quality: an analysis of 91 national household surveys. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1186–95. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30389-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen PH, Khương LQ, Pramanik P, et al. Effective coverage of nutrition interventions across the continuum of care in Bangladesh: insights from nationwide cross-sectional household and health facility surveys. BMJ Open 2021;11:e040109. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amouzou A, Leslie HH, Ram M, et al. Advances in the measurement of coverage for RMNCH and nutrition: from contact to effective coverage. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001297. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marsh AD, Muzigaba M, Diaz T, et al. Effective coverage measurement in maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health and nutrition: progress, future prospects, and implications for quality health systems. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e730–6. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30104-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leslie HH, Malata A, Ndiaye Y, et al. Effective coverage of primary care services in eight high-mortality countries. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000424. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang W, Mallick L, Allen C, et al. Effective coverage of facility delivery in Bangladesh, Haiti, Malawi, Nepal, Senegal, and Tanzania. PLoS One 2019;14:e0217853. 10.1371/journal.pone.0217853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Bank Group . World Bank Open Data | Data [Internet]. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/ [Accessed 02 Jan 2022].

- 14.World Health Organization . Regional Office for the Western Pacific. The Kingdom of Cambodia health system review [Internet].WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. xxxii, 2015: 178 p. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/208213 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statistics/Cambodia NI of, Health/Cambodia DG for, International ICF . Cambodia demographic and health survey 2014, 2015. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr312-dhs-final-reports.cfm [Accessed 05 Nov 2021].

- 16.Pierce H. Increasing health facility deliveries in Cambodia and its influence on child health. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:67. 10.1186/s12939-019-0964-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liljestrand J, Sambath MR. Socio-Economic improvements and health system strengthening of maternity care are contributing to maternal mortality reduction in Cambodia. Reprod Health Matters 2012;20:62–72. 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39620-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, et al. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet 2018;392:2203–12 https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618316684 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31668-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimenez-Soto E, Durham J, Hodge A. Entrenched geographical and socioeconomic disparities in child mortality: trends in absolute and relative inequalities in Cambodia. PLoS One 2014;9:e109044. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong R, Them R. Inequality in access to health care in Cambodia: socioeconomically disadvantaged women giving birth at home assisted by unskilled birth attendants. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015;27:NP1039–49. 10.1177/1010539511428351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W, Hong R. Levels and determinants of continuum of care for maternal and newborn health in Cambodia-evidence from a population-based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:62. 10.1186/s12884-015-0497-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chomat AM, Grundy J, Oum S, et al. Determinants of utilisation of intrapartum obstetric care services in Cambodia, and gaps in coverage. Glob Public Health 2011;6:890–905. 10.1080/17441692.2011.572081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chham S, Radovich E, Buffel V, et al. Determinants of the continuum of maternal health care in Cambodia: an analysis of the Cambodia demographic health survey 2014. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:410. 10.1186/s12884-021-03890-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rutstein SO, Rojas G. Guide to DHS statistics.;171. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . Who recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MoH/UNFPA . National Strategy for Reproductive and Sexual Health in Cambodia, 2017-2020 [Internet], 2017. Available: https://cambodia.unfpa.org/en/publications/national-strategy-reproductive-and-sexual-health-cambodia-2017-2020

- 27.World Health Organization . Standards for improving the quality of care for children and young adolescents in health facilities, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.USAID . Standard Recode Manual for DHS 6 [Internet]. MEASURE DHS/ICF International, 2013. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-dhsg4-dhs-questionnaires-and-manuals.cfm [Accessed 22 Nov 2021].

- 29.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index, 2004. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-cr6-comparative-reports.cfm [Accessed 22 Apr 2022].

- 30.Cummings P. Estimating adjusted risk ratios for matched and unmatched data: an update. Stata J 2011;11:290–8. 10.1177/1536867X1101100208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arsenault C, Kim MK, Aryal A, et al. Hospital-provision of essential primary care in 56 countries: determinants and quality. Bull World Health Organ 2020;98:735–46. 10.2471/BLT.19.245563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Planning & Health Information . The Third Health Strategic Plan 2016-2020 (HSP3) [Internet], 2016 May. Available: http://hismohcambodia.org/public/fileupload/carousel/HSP3-(2016-2020).pdf

- 33.Annear PL, Tayu Lee J, Khim K, et al. Protecting the poor? impact of the National health equity fund on utilization of government health services in Cambodia, 2006-2013. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001679. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaba MW, Baesel K, Poch B, et al. IDPoor: a poverty identification programme that enables collaboration across sectors for maternal and child health in Cambodia. BMJ 2018;363:k4698. 10.1136/bmj.k4698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee H-Y, Heo J, Koh H. Effect of a comprehensive program on maternal and child healthcare service in Battambang, Cambodia: a multivariate difference-in-difference analysis. J Glob Health Sci 2019;1. 10.35500/jghs.2019.1.e2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ir P, Korachais C, Chheng K, et al. Boosting facility deliveries with results-based financing: a mixed-methods evaluation of the government midwifery incentive scheme in Cambodia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:170. 10.1186/s12884-015-0589-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kikuchi K, Ansah EK, Okawa S, et al. Effective linkages of continuum of care for improving neonatal, perinatal, and maternal mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139288. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization . World malaria report. Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okawa S, Win HH, Leslie HH, et al. Quality gap in maternal and newborn healthcare: a cross-sectional study in Myanmar. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001078. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leslie HH, Sun Z, Kruk ME. Association between infrastructure and observed quality of care in 4 healthcare services: a cross-sectional study of 4,300 facilities in 8 countries. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002464. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen PT, Rahman MS, Le PM, et al. Trends in, projections of, and inequalities in reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health service coverage in Vietnam 2000-2030: a Bayesian analysis at national and sub-national levels. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021;15:100230. 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The DHS Program - Cambodia . Standard DHS, 2021 [Internet]. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey/survey-display-558.cfm [Accessed 26 Nov 2021].

- 43.Facility GF. Preserve Essential Health Services During the Covid-19 Pandemic Cambodia [Internet]. Available: https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/sites/gff_new/files/documents/Cambodia-Covid-Brief_GFF.pdf

- 44.Arsenault C, Gage A, Kim MK. COVID-19 and resilience of healthcare systems in ten countries. Nat Med 2022:1–11. 10.1038/s41591-022-01750-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hazir T, Begum K, El Arifeen S, et al. Measuring coverage in MNCH: a prospective validation study in Pakistan and Bangladesh on measuring correct treatment of childhood pneumonia. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001422. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stanton CK, Rawlins B, Drake M, et al. Measuring coverage in MNCH: testing the validity of women's self-report of key maternal and newborn health interventions during the Peripartum period in Mozambique. PLoS One 2013;8:e60694. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryce J, Arnold F, Blanc A, et al. Measuring coverage in MNCH: new findings, new strategies, and recommendations for action. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001423. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Neill K, Takane M, Sheffel A, et al. Monitoring service delivery for universal health coverage: the service availability and readiness assessment. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:923–31. 10.2471/BLT.12.116798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-062028supp001.pdf (88.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are available upon request and available online from www.measuredhs.com.