Abstract

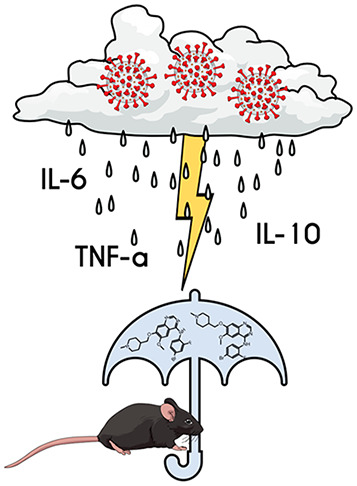

The portfolio of SARS-CoV-2 small molecule drugs is currently limited to a handful that are either approved (remdesivir), emergency approved (dexamethasone, baricitinib, paxlovid, and molnupiravir), or in advanced clinical trials. Vandetanib is a kinase inhibitor which targets the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), as well as the RET-tyrosine kinase. In the current study, it was tested in different cell lines and showed promising results on inhibition versus the toxic effect on A549-hACE2 cells (IC50 0.79 μM) while also showing a reduction of >3 log TCID50/mL for HCoV-229E. The in vivo efficacy of vandetanib was assessed in a mouse model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and statistically significantly reduced the levels of IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α and mitigated inflammatory cell infiltrates in the lungs of infected animals but did not reduce viral load. Vandetanib also decreased CCL2, CCL3, and CCL4 compared to the infected animals. Vandetanib additionally rescued the decreased IFN-1β caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice to levels similar to that in uninfected animals. Our results indicate that the FDA-approved anticancer drug vandetanib is worthy of further assessment as a potential therapeutic candidate to block the COVID-19 cytokine storm.

Introduction

Currently, three vaccines are approved for SARS-CoV-2 in the USA,1−3 and only a few drugs are approved for use including remdesivir.4 An emergency use authorization allows the protein kinase inhibitor baricitinib to be combined with remdesivir for the treatment of children above 2 years old and adults admitted to the hospital that need respiratory support.5 Dexamethasone is recommended for certain severe COVID-19 patients that are hospitalized.6 As these limited treatment options and several drugs in clinical trials7 attest, there is a global need for more therapeutic options for COVID-19. Such small molecule antivirals can be used outside of hospitals, while additional treatments to address the many symptoms of COVID-19 that are termed long-COVID8,9 are also needed. Pfizer developed the SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor PF-07321332 targeting Mpro, in combination with ritonavir (paxlovid), which was granted emergency approval by FDA. Direct acting antivirals target early stage virus replication, and most of the research efforts have been focused on finding such molecules; however, these might have a short therapeutic window, which would render them less effective if administered during the immunopathogenic phase of the disease. The cytokine storm is a major concern with COVID-19 disease,10 and new drugs are urgently needed for this, as well. Dexamethasone has been shown to improve the survival of patients when given to those with an oxygen requirement.11

The cytokine storm is caused by an imbalance in the immune system,10 and it progresses to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and can also cause multiple organ failure.10,12 Several cytokines and chemokines are increased during SARS-CoV-2 infection, and they can recruit and activate several immune cell types, such as neutrophils, macrophages, and T-lymphocytes.13 Measuring these cytokines/chemokines may help in predicting the mortality risk of infected patients.14

Studies have revealed higher levels of cytokine storm associated with more severe COVID-19 development.12 In these patients, the inflammatory substances from the cytokine storm destroy tissues, which can lead to ARDS and multiorgan failure,15 an important cause of death. Capillary leakage caused by inflammation driven by TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1, IL-8, and VEGF is one of the main causes of damaging lung function in COVID-19, leading to ARDS.12 Another important factor is that SARS-CoV-2 can interrupt the type I interferon (IFN-α and -β) release during infection by the host innate immune system,16,17 and this delayed response of type I IFN signaling allows viral replication that can cause tissue damage.18

Targeting the cytokine storm to ameliorate the hyperinflammatory state could be a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of COVID-19.13,19−21 It was previously demonstrated that the modulation of host cell signaling is essential for viral replication, and it could be therapeutically relevant.22,23 Minimizing or preventing the cytokine storm is still a significant challenge, and providing more targeted therapeutic approaches may allow for an earlier anticytokine treatment and prevention of ARDS and deaths. Multiple protein kinase inhibitors have demonstrated in vitro24−29 and in vivo activity for SARS-CoV-2, while several have been tested in clinical trials.30,31 In the current study, we evaluated vandetanib in A549-ACE2 and Caco-2 cells infected by SARS-CoV-2, followed by an in vivo efficacy study of vandetanib in an acute infection model using K18-hACE2 mice challenged with SARS-CoV-2.

Results

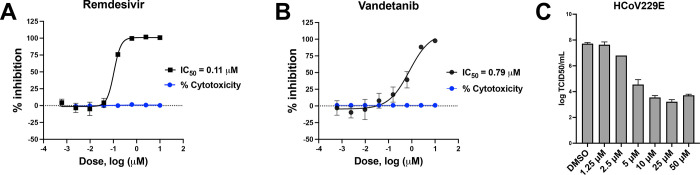

Vandetanib Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Replication In Vitro without Cell Toxicity

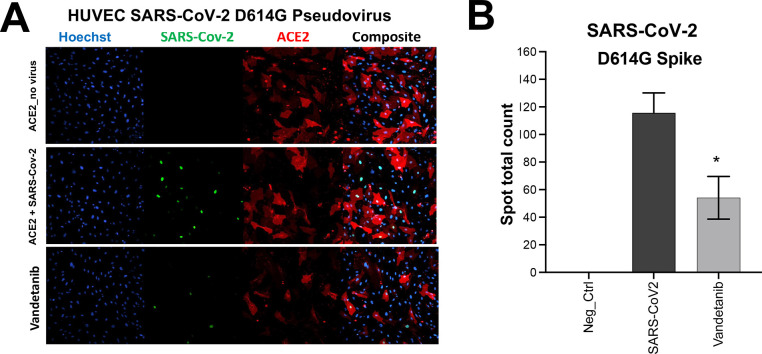

Initially, vandetanib was tested in DBT cells infected with murine hepatitis virus (MHV), which was used as a model of SARS-CoV-2 replication to evaluate its antiviral activity (IC50 1.60 μM, Figure S1). Vandetanib was also characterized in A549-ACE2 cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 using remdesivir as a positive control. Cells were incubated with compounds 1 h before the SARS-CoV-2 infection, and vandetanib (IC50 0.79 μM, SI > 12.6) showed lower potency than remdesivir (IC50 of 0.11 μM, SI > 90) (Figure 1A,B). Vandetanib was further tested in Caco-2 cells and showed an IC90 of 2 μM, SI = 2 (Table S1) as well as showed a reduction of >3 log TCID50/mL with HCoV-229E when tested at 5 μM (Figure 1C). We used a VSV-pseudotype SARS-CoV-2 assay to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein-mediated entry, and our results demonstrated that vandetanib was active at 1 μM in the SARS-CoV-2 D614G strain (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 1.

Characterization of vandetanib. SARS-CoV-2 inhibition and cytotoxicity were tested in the A549-ACE2 cell line: (A) remdesivir (SI > 90) and (B) vandetanib (SI > 12.6). (C) HCoV229E antiviral assay with vandetanib.

Figure 2.

Pseudo-SARS-CoV-2 D614G baculovirus (Montana Molecular #C1110G, #C1120G) assay in the presence of (A) vandetanib at 1 μM and its (B) graphical analysis.

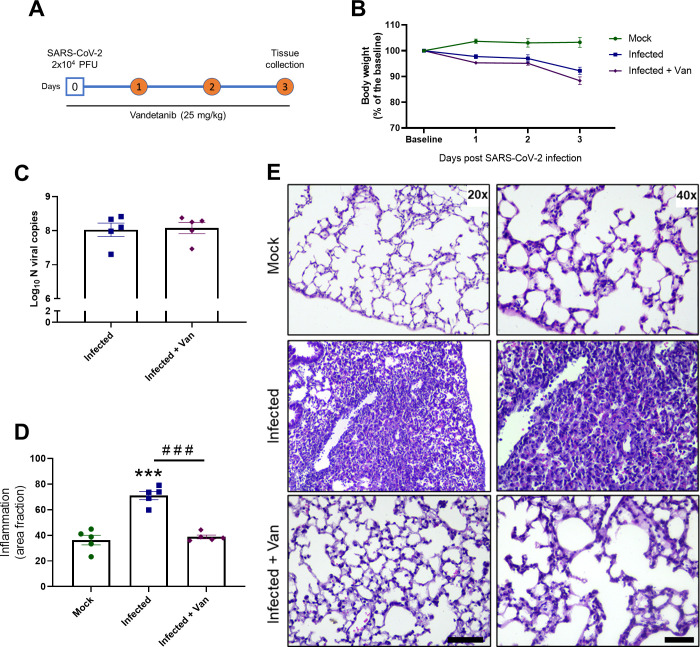

In Vivo Efficacy of Vandetanib in Mice

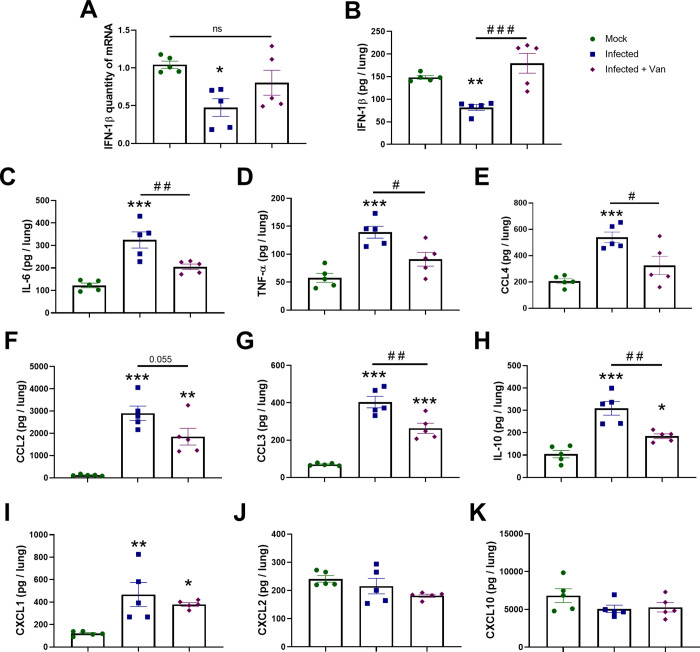

We used the K18-hACE2 mouse model of COVID-19 to evaluate the in vivo efficacy of vandetanib32−34 (8 week old females, challenged with SARS-CoV-2 2 × 104 PFU in 40 μL, intranasally). Vandetanib (25 mg/kg) was administered i.p. 1 h prior to infection and once a day subsequently for 3 days postinfection (3 dpi) (Figure 3A). Mice were euthanized on 3 dpi, and lung histopathology, cytokine levels, as well as viral load were evaluated. The group treated with vandetanib and the untreated mice lost weight compared to the control group of uninfected animals, which only received vehicle formulation (Figure 3B). We used RT-PCR to evaluate lung viral load, and although vandetanib reduced SARS-CoV-2 infection in A549-ACE2 cells, no significant reduction in viral RNA levels was observed in vivo when compared with the infected untreated mice (Figure 3C). While vandetanib did not decrease the viral load, it had a statistically significant protective effect on the lung pathology (Figure 3D,E). The untreated mice group infected with SARS-Cov-2 showed severe pathological alterations with infiltration of inflammatory cells. Vandetanib treatment showed milder infiltration and improved morphology even in the absence of the effect on the viral load. These results may indicate an effect of vandetanib on the virus-induced inflammatory process. Further analyses also showed that vandetanib treatment restored the levels of IFN-1β (Figure 4A,B) and prevented the increase of the levels of the most widely evaluated inflammatory cytokines/chemokines observed in infected mice. Vandetanib reduced IL-6, TNF-α, and CCL4 (compared with infected untreated animals) to levels similar to those found in uninfected animals (Figure 4C–E). Vandetanib also significantly reduced the levels of CCL2, CCL3, and IL-10 compared to infected animals (Figure 4F–H). CXCL1 was not affected by the treatment (Figure 4I), while CXCL2 and CXCL10 were not elevated in infected animals (Figure 4J,K). Combined, these results indicate that vandetanib reduces the cytokine storm rather than reducing SARS-CoV-2 replication in the COVID-19 mouse model that was used in this study.

Figure 3.

In vivo efficacy of vandetanib in a mouse model of COVID-19. (A) Experimental timeline: K18-hACE2 tg mice mock or infected with SARS-CoV-2 (2 × 104 PFU/40 μL saline, intranasal). Vandetanib group was treated with 25 mg/kg i.p. 1 h before virus infection. (B) Body weight was measured once a day. (C) Mice were euthanized after 3 dpi and (C) lung viral load and (D,E) lung histopathology was evaluated; ***p < 0.001 in comparison with the uninfected mock group after one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey posthoc test; ###p < 0.001 in comparison with the infected group after one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey posthoc test. Scale bar = 20×, 125 μm; 40×, 50 μm.

Figure 4.

Vandetanib decreases lung inflammation in a mouse model of COVID-19. (A) Expression of IFN-1β quantified by qPCR. Levels of (B) IFN-1β, (C) IL-6, (D) TNF-α, (E) CCL4, (F) CCL2, (G) CCL3, (H) IL-10, (I) CXCL1, (J) CXCL2, and (K) CXCL10 measured by ELISA; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 in comparison with mock group after one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey posthoc test; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 in comparison with the infected group after one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey posthoc test.

Discussion

With mounting COVID-19 infections and global death toll over 6.3 M to date (June 2022), there has been a focus on ensuring the global population are vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2. Still, we are in a race against rapidly emerging viral variants that may hamper the vaccines’ future effectiveness,35 while many countries still have little or no access to the vaccines that are available in the USA and Europe after over 2 years of this pandemic.36 There is also a critical need to develop treatments that do not require cold chain storage and can be used outside of hospitals.

Growth factor receptor signaling pathways were described to be highly activated upon infection by SARS-CoV-2, hence inhibition of these pathways prevents replication in cells.37 Vandetanib is an FDA-approved drug used to treat thyroid gland tumors (targeting VEGFR, EGFR, and RET-tyrosine kinase38) and was active in both A549-ACE2 and Caco-2 cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 and against HCoV-229E. Based on this in vitro activity profile, it was selected for further preclinical testing in a COVID-19 mouse model.

One of the major causes of ARDS and multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS) observed in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection is the cytokine storm.12,15 Some regulators of thrombotic markers, which include IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and NF-kB, were identified in severe and critical patients with COVID-19.39 Our evaluation of the in vivo efficacy of vandetanib in a murine model of infection demonstrated that vandetanib reduced IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α compared to the infected untreated animals to levels similar to those found in uninfected animals. The levels of several inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including PDGF, TNF, IL-6, and VEGF are significantly increased in severe COVID-19 patients.40 IL-6 has also been shown to correlate with respiratory failure and adverse clinical outcomes.15,41 Furthermore, a recent clinical study demonstrated that those patients with ARDS showed higher levels of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 in comparison to the non-ARDS group, and that the levels of those cytokines are associated significantly with disseminated intravascular coagulation.15 The levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were also higher in ARDS patients with acute kidney injury.15 Thus, reducing the levels of these cytokines upon treatment with vandetanib could improve prognosis in COVID-19. The host innate immune response releases cytokines such as type I interferon (IFN-α and -β) during infection, which initiates antiviral activity. However, SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural proteins can interrupt this particular response.16,17 One interesting observation is that vandetanib rescued the decreased IFN-1β caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice to levels similar to that in uninfected animals (Figure 4A). Vandetanib also decreased CCL2, CCL3, and CCL4 compared to infected animals (Figure 4F,G,E,I). These chemokines have been reported to be increased in patients with COVID-19.14 CXCL1 is highly expressed in macrophages involved in SARS-CoV-2 infection, and it is a chemoattractant for neutrophils.42 CCL2 levels were also independently correlated with mortality in COVID-19 patients, and it is known to be responsible for regulation of monocyte/macrophage migration and infiltration.43 Finally, CCL2 expression has been shown to be significantly elevated in patients with unfavorable disease outcome.44 Therefore, targeting the receptor binding of chemokines and cytokines might be a good strategy to decrease higher activation of immune cells in patients with critical COVID-19.42

Mice treated with vandetanib showed a significant treatment effect with mild infiltration, looking like uninfected mice in the histological examination of lungs. VEGF expression can be induced by dyspnea and hypoxia in lung tissues caused by ARDS. VEGF is a potent vascular permeabilizing agent and participates in lung inflammation45 and can induce vascular leakiness and pulmonary edema in the lungs of COVID-19 patients, which subsequently increases hypoxia.46,47 Therefore, any therapies that can block the signaling mediated by VEGF and the VEGF receptor could improve oxygen perfusion and anti-inflammatory response in critical COVID-19 patients. In agreement, bevacizumab, which is a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, showed improvement of oxygenation and reduced the duration of oxygen support and no deaths in severe COVID-19 patients (NCT04275414).48 Therefore, modulating VEGF using small molecule drugs such as vandetanib38 may have some clinical utility.

Kinase inhibitors can modulate several host cell targets involved in multiple virus steps of the life cycle and have been used as broad-spectrum antiviral therapies.49 Kinase inhibitors also have anti-inflammatory and cytokine inhibitory activity properties which may address lung damage from respiratory virus infections.49 Host-targeting antivirals also offer the advantage that they can exploit the host protein and pathways needed for the replication of the virus and might decrease the risk of developing resistance against them, as well.

Although we observed that vandetanib reduced SARS-CoV-2 infection in A549-ACE2 cells with a reduction of >3 log TCID50/mL of HCoV-229E and decreased viral entry in the pseudovirus assay, surprisingly, we did not observe any statistically significant reduction in the viral load in the SARS-CoV-2 mouse model. We also did not observe a decrease in the viral load with the group treated with remdesivir. Remdesivir is degraded by a serum esterase, and to perform studies in mice that mirror the pharmacokinetics and exposure that is seen in humans, Ces1c–/– mice which lack the serum esterase should be used.50 While our results may represent a suboptimal remdesivir dose, it demonstrated a positive effect on the lung pathology in mice that was comparable to that with vandetanib versus the control. The positive effects shown in our study regarding modulation of the main inflammatory cytokines and chemokines as well as prevention of lung damage demonstrated that vandetanib likely has the potential to address the cytokine storm associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although remdesivir was previously shown to decrease hospitalization time in COVID-1951 patients, only anti-inflammatory approaches have improved survival in these patients, such as dexamethasone when given to those with an oxygen requirement.11 A randomized, placebo-controlled trial using tofacitinib (Janus kinase inhibitor), with the concurrent use of glucocorticoid treatment, was reported to improve survival in COVID-19 patients.52 The SAVE-MORE trial showed that treatment with anakinra, which is recombinant human IL-1 receptor antagonist, significantly reduced the risk of worse clinical outcome in patients that were hospitalized with moderate and severe COVID-19.53

Minimizing or preventing the COVID-19-induced cytokine storm is still a significant challenge, as it will require definition of the timing for immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory agent administration. Knowing which cytokines/chemokines are important to target in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia and providing more targeted therapeutic approaches may allow for the earlier introduction of treatments of the cytokine storm. We now report that vandetanib can decrease levels in mice of several important cytokines that are significantly elevated in the COVID-19-related cytokine storm, such as IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α, and also decrease chemokines CCL2, CCL3, and CCL4. Whether this COVID-19 mouse study translates to humans infected with this virus requires further clinical research outside the scope of this study.

Conclusions

There is continued interest in kinase inhibitors for treating COVID-19, and several such as masitinib54 and others are in clinical trials.24 We now report that the FDA-approved kinase inhibitor vandetanib could be a potential drug to target the cytokine storm and prevent patients from developing ARDS. Treatment with vandetanib in the mouse model reduced key inflammatory cytokines. Vandetanib is well absorbed from the gut, reaching peak blood plasma concentrations 4–10 h after application, and has an average half-life of 19 days.55,56 The pharmacokinetic properties of vandetanib were reported to be linear over the dosage range of 50–1200 mg/day. In patients with thyroid medullary cancer, using a dose of 300 mg can reach a maximum plasma concentration of 857 ng/mL after 6 h. Vandetanib is metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and is predominantly excreted via the feces and urine, while it has a terminal excretion half-life of 20 days.38 In a study in healthy patients with dose escalation up to 1200 mg/day, vandetanib appeared to be well tolerated in the populations studied, and at the dose of 800 mg/kg, vandetanib can reach a Cmax of 1 μM.55 Vandetanib is FDA-approved and sold under the name Caprelsa (Sanofi Genzyme) in dosage forms of 100 and 300 mg. In our mouse studies, we used 25 mg/kg, which could potentially be extrapolated57 to a daily human dose of approximately 300 mg. When combined, these pharmacokinetic and the host effects leading to the prevention of lung inflammation may suggest that vandetanib has the potential to address the cytokine storm caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection that could be investigated in future clinical studies of COVID-19. While we are aware of at least one report of a patient treated with vandetanib who had COVID-19 and recovered,58 to date, it has not been assessed further in a clinical trial, which this current study may point toward.

Materials and Methods

Compounds

Vandetanib was purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE, Monmouth Junction, NJ).

SARS-CoV-2 Tested in A549-ACE2 Cells

This assay was performed as described previously,59 using A549-ACE2 mock cells or infected cells at a MOI of 0.02 with SARS-CoV-2-nLuc.60 The drugs (2×) were administered to the cells 1 h before the infection. Cytotoxicity and viral growth were evaluated 48 h postinfection using Nano-Glo luciferase and CytoTox-Glo cytotoxicity assays (Promega), respectively. Replication and toxicity were normalized to the vehicle wells on each plate.

SARS-CoV-2 Tested in Caco-2 Cells

The methodology for the reduction of virus yield (VYR) assay in the Caco-2 is identical to the Vero 76 cell assay described previously,59 and the EC90 is reported.

Murine Hepatitis Virus

Vandetanib was tested for antiviral activity against the murine hepatitis virus (MHV) infection in DBT cells. This system was used initially as a model for SARS-CoV-2 infection, and experiments were performed as described previously.61

HCoV 229E Antiviral Assay

This assay was performed as described previously.59 CPE was monitored by visual inspection at 96 h postinfection and TCID50 titers were calculated.62,63

Pseudovirus Assay

We used the kit pseudo-SARS-CoV-2 D614G Green Reporter (Montana Molecular #C1120G), and experiments were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cell imaging and analysis were conducted at Phenovista Biosciences. Compounds were diluted to 1 μM and maintained for 60 min with 2 × 109 VG/mL of pseudo-SARS-CoV-2 or pseudo-SARS-CoV-2 D614G baculovirus (Montana Molecular #C1110G, #C1120G). Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst, and images were acquired with the high content screening InCell analyzer HS6500 microscope (20× magnification) prior to fixation with PFA. Quantitative analysis was performed with the ThermoFisher HCS Studio Cell analysis suite.

K18-hACE2 Mice Infection

SARS-CoV-2 was isolated from a COVID-19 positive-tested patient.64 We used K18-hACE2 humanized mice (B6.Cg-Tg(K18-ACE2)2Prlmn/J)32,65,66 from Jackson Laboratory, which has been used as model for SARS-CoV-2-induced disease.65−71 Mice were breed in the Centro de Criação de Animais Especiais (Ribeirão Preto Medical School/University of São Paulo). Experiments were approved by the University of Sao Paulo ethics committee (protocol number 105/2021). Mice had access to food and water ad libitum. Animals were transferred to the BSL3 facility for the experimental infection.

SARS-CoV-2 Experimental Infection and Treatments

The experiments were performed as previously described64 with a few modifications. Female K18-hACE2 mice (8 weeks of age) were infected intranasally with 2 × 104 PFU of SARS-CoV-2 (in 40 μL), while uninfected mice received 40 μL of PBS. Animals were treated with vandetanib (25 mg/kg, i.p.) (n = 6) 1 h before virus inoculation on the day of infection. Five infected animals were not treated with the drug and were used as a control group. Vandetanib was also given once daily on days 1, 2, and 3 dpi. Body weight was evaluated daily, and animals were humanely euthanized on the day 3 dpi. Lungs were used for ELISA assay, viral load analysis, and histological assessment, as described previously.64

Absolute Viral Copy Quantification

A total of 800 ng of RNA from the lung was used to synthesize cDNA. cDNA synthesis and the absolute copy quantification were performed as described previously.64

ELISA Assay

ELISA assay was performed with lung homogenate as described previously.64 The following cytokines and chemokines were measured: IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-1β, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL10, CCL2, CCL3, and CCL4.

Lung Histopathological Process and Analyses

Lung histopathology was performed as described previously.64 Morphometric analysis was conducted in accordance the American Thoracic Society and European Thoracic Society (ATS/ERS) protocol.72

Acknowledgments

Dr. Mindy Davis and colleagues are gratefully acknowledged for assistance with the NIAID virus screening capabilities. The authors kindly acknowledge the technical assistance of Ieda Regina dos Santos, Marcella Daruge Grando, Juliana Trench Abumansur, and Felipe Souza. We greatly appreciate Dr. Anne M. Quinn from Montana Molecular for her generous assistance with pseudovirus testing.

Glossary

Abbreviations Used

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease

- ACE2

angiotensin converting enzyme 2

- MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c02794.

Vandetanib MHV and vandetanib Caco-2 data (PDF)

Author Contributions

† A.C.P. and G.F.G. contributed equally.

We kindly acknowledge NIH funding, 1R43AT010585-01 from NIH/NCCAM to S.E. and AI142759 and AI108197 to R.S.B. This project was also supported by the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with funding from the North Carolina Coronavirus Relief Fund established and appropriated by the North Carolina General Assembly. J.A.L. and N.J.J. were supported by the Comparative Medicine Institute at North Carolina State University through its CAVE initiative. T.M.C., J.C.A.F., and F.Q.C. received funding from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) under Grant Agreement Nos. 2013/08216-2 (Center for Research in Inflammatory Disease) and 2020/04860-8 and from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (project 88887.507155/2020–00). Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, Inc. has utilized the nonclinical and preclinical services program offered by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): S.E. and A.C.P. are employees of Collaborations Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rehman M. F. U.; Fariha C.; Anwar A.; Shahzad N.; Ahmad M.; Mukhtar S.; Farhan Ul Haque M. Novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: A recent mini review. Comput. Struct Biotechnol J. 2021, 19, 612–623. 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakidis N. C.; López-Cortés A.; González E. V.; Grimaldos A. B.; Prado E. O. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines strategies: a comprehensive review of phase 3 candidates. NPJ. Vaccines 2021, 6 (1), 28. 10.1038/s41541-021-00292-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. Y.; Wang S. H.; Tang Y.; Sheng W.; Zuo C. J.; Wu D. W.; Fang H.; Du Q.; Li N. Landscape and progress of global COVID-19 vaccine development. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 3276–3280. 10.1080/21645515.2021.1945901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman R. T.; Roth J. S.; Brimacombe K. R.; Simeonov A.; Shen M.; Patnaik S.; Hall M. D. Remdesivir: A Review of Its Discovery and Development Leading to Emergency Use Authorization for Treatment of COVID-19. ACS Cent Sci. 2020, 6 (5), 672–683. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A. C.; Patterson T. F.; Mehta A. K.; Tomashek K. M.; Wolfe C. R.; Ghazaryan V.; Marconi V. C.; Ruiz-Palacios G. M.; Hsieh L.; Kline S.; Tapson V.; Iovine N. M.; Jain M. K.; Sweeney D. A.; El Sahly H. M.; Branche A. R.; Regalado Pineda J.; Lye D. C.; Sandkovsky U.; Luetkemeyer A. F.; Cohen S. H.; Finberg R. W.; Jackson P. E.H.; Taiwo B.; Paules C. I.; Arguinchona H.; Erdmann N.; Ahuja N.; Frank M.; Oh M.-d.; Kim E.-S.; Tan S. Y.; Mularski R. A.; Nielsen H.; Ponce P. O.; Taylor B. S.; Larson L.; Rouphael N. G.; Saklawi Y.; Cantos V. D.; Ko E. R.; Engemann J. J.; Amin A. N.; Watanabe M.; Billings J.; Elie M.-C.; Davey R. T.; Burgess T. H.; Ferreira J.; Green M.; Makowski M.; Cardoso A.; de Bono S.; Bonnett T.; Proschan M.; Deye G. A.; Dempsey W.; Nayak S. U.; Dodd L. E.; Beigel J. H. Baricitinib plus Remdesivir for Hospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N Engl J. Med. 2021, 384 (9), 795–807. 10.1056/NEJMoa2031994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horby P.; Lim W. S.; Emberson J. R.; Mafham M.; Bell J. L.; Linsell L.; Staplin N.; Brightling C.; Ustianowski A.; Elmahi E.; Prudon B.; Green C.; Felton T.; Chadwick D.; Rege K.; Fegan C.; Chappell L. C.; Faust S. N.; Jaki T.; Jeffery K.; Montgomery A.; Rowan K.; Juszczak E.; Baillie J. K.; Haynes R.; Landray M. J.; Group R. C. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J. Med. 2021, 384 (8), 693–704. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apaydin C. B.; Cinar G.; Cihan-Ustundag G. Small-molecule antiviral agents in ongoing clinical trials for COVID-19. Curr. Drug Targets 2021, 22, 1986–2005. 10.2174/1389450122666210215112150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbandian A.; Sehgal K.; Gupta A.; Madhavan M. V.; McGroder C.; Stevens J. S.; Cook J. R.; Nordvig A. S.; Shalev D.; Sehrawat T. S.; Ahluwalia N.; Bikdeli B.; Dietz D.; Der-Nigoghossian C.; Liyanage-Don N.; Rosner G. F.; Bernstein E. J.; Mohan S.; Beckley A. A.; Seres D. S.; Choueiri T. K.; Uriel N.; Ausiello J. C.; Accili D.; Freedberg D. E.; Baldwin M.; Schwartz A.; Brodie D.; Garcia C. K.; Elkind M. S. V.; Connors J. M.; Bilezikian J. P.; Landry D. W.; Wan E. Y. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27 (4), 601–615. 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva Andrade B.; Siqueira S.; de Assis Soares W. R.; de Souza Rangel F.; Santos N. O.; Dos Santos Freitas A.; Ribeiro da Silveira P.; Tiwari S.; Alzahrani K. J.; Góes-Neto A.; Azevedo V.; Ghosh P.; Barh D. Long-COVID and Post-COVID Health Complications: An Up-to-Date Review on Clinical Conditions and Their Possible Molecular Mechanisms. Viruses 2021, 13 (4), 700. 10.3390/v13040700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costela-Ruiz V. J.; Illescas-Montes R.; Puerta-Puerta J. M.; Ruiz C.; Melguizo-Rodríguez L. SARS-CoV-2 infection: The role of cytokines in COVID-19 disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 54, 62–75. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horby P.; Lim W. S.; Emberson J. R.; Mafham M.; Bell J. L.; Linsell L.; Staplin N.; Brightling C.; Ustianowski A.; Elmahi E.; Prudon B.; Green C.; Felton T.; Chadwick D.; Rege K.; Fegan C.; Chappell L. C.; Faust S. N.; Jaki T.; Jeffery K.; Montgomery A.; Rowan K.; Juszczak E.; Baillie J. K.; Haynes R.; Landray M. J. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J. Med. 2021, 384 (8), 693–704. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R.; Lan Z.; Ye J.; Pang L.; Liu Y.; Wu W.; Qin X.; Guo Y.; Zhang P. Cytokine Storm: The Primary Determinant for the Pathophysiological Evolution of COVID-19 Deterioration. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 589095. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.589095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roshanravan N.; Seif F.; Ostadrahimi A.; Pouraghaei M.; Ghaffari S. Targeting Cytokine Storm to Manage Patients with COVID-19: A Mini-Review. Arch Med. Res. 2020, 51 (7), 608–612. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coperchini F.; Chiovato L.; Ricci G.; Croce L.; Magri F.; Rotondi M. The cytokine storm in COVID-19: Further advances in our understanding the role of specific chemokines involved. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021, 58, 82–91. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Yang X.; Li Y.; Huang J. A.; Jiang J.; Su N. Specific cytokines in the inflammatory cytokine storm of patients with COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome and extrapulmonary multiple-organ dysfunction. Virol J. 2021, 18 (1), 117. 10.1186/s12985-021-01588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H.; Cao Z.; Xie X.; Zhang X.; Chen J. Y.; Wang H.; Menachery V. D.; Rajsbaum R.; Shi P. Y. Evasion of Type I Interferon by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep 2020, 33 (1), 108234. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen C. K.; Lam J. Y.; Wong W. M.; Mak L. F.; Wang X.; Chu H.; Cai J. P.; Jin D. Y.; To K. K.; Chan J. F.; Yuen K. Y.; Kok K. H. SARS-CoV-2 nsp13, nsp14, nsp15 and orf6 function as potent interferon antagonists. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020, 9 (1), 1418–1428. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1780953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Zhao C.; Zhao W. Virus Caused Imbalance of Type I IFN Responses and Inflammation in COVID-19. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 633769. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.633769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein S.; Herbert J. A.; McNamara P. S.; Hedrich C. M. COVID-19: Immunology and treatment options. Clin Immunol 2020, 215, 108448. 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter A. E.; Sandeep B. V.; Rao B. G.; Kalpana V. L. Calming the Storm: Natural Immunosuppressants as Adjuvants to Target the Cytokine Storm in COVID-19. Front Pharmacol 2021, 11, 583777. 10.3389/fphar.2020.583777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradian N.; Gouravani M.; Salehi M. A.; Heidari A.; Shafeghat M.; Hamblin M. R.; Rezaei N. Cytokine release syndrome: inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines as a solution for reducing COVID-19 mortality. Eur. Cytokine Netw 2020, 31 (3), 81–93. 10.1684/ecn.2020.0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli C.; Yakimovich A.; Kilcher S.; Reynoso G. V.; Fläschner G.; Müller D. J.; Hickman H. D.; Mercer J. Vaccinia virus hijacks EGFR signalling to enhance virus spread through rapid and directed infected cell motility. Nat. Microbiol 2019, 4 (2), 216–225. 10.1038/s41564-018-0288-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleschka S.; Wolff T.; Ehrhardt C.; Hobom G.; Planz O.; Rapp U. R.; Ludwig S. Influenza virus propagation is impaired by inhibition of the Raf/MEK/ERK signalling cascade. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3 (3), 301–5. 10.1038/35060098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg E.; Parent A.; Yang P. L.; Sattler M.; Liu Q.; Liu Q.; Wang J.; Meng C.; Buhrlage S. J.; Gray N.; Griffin J. D. Repurposing of Kinase Inhibitors for Treatment of COVID-19. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37 (9), 167. 10.1007/s11095-020-02851-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranov M. V.; Bianchi F.; van den Bogaart G. The PIKfyve Inhibitor Apilimod: A Double-Edged Sword against COVID-19. Cells 2021, 10 (1), 30. 10.3390/cells10010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T. N.; Pino M.; Boddapati A. K.; Viox E. G.; Starke C. E.; Upadhyay A. A.; Gumber S.; Nekorchuk M.; Busman-Sahay K.; Strongin Z.; Harper J. L.; Tharp G. K.; Pellegrini K. L.; Kirejczyk S.; Zandi K.; Tao S.; Horton T. R.; Beagle E. N.; Mahar E. A.; Lee M. Y. H.; Cohen J.; Jean S. M.; Wood J. S.; Connor-Stroud F.; Stammen R. L.; Delmas O. M.; Wang S.; Cooney K. A.; Sayegh M. N.; Wang L.; Filev P. D.; Weiskopf D.; Silvestri G.; Waggoner J.; Piantadosi A.; Kasturi S. P.; Al-Shakhshir H.; Ribeiro S. P.; Sekaly R. P.; Levit R. D.; Estes J. D.; Vanderford T. H.; Schinazi R. F.; Bosinger S. E.; Paiardini M. Baricitinib treatment resolves lower-airway macrophage inflammation and neutrophil recruitment in SARS-CoV-2-infected rhesus macaques. Cell 2021, 184 (2), 460–475. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Chen C. Z.; Swaroop M.; Xu M.; Wang L.; Lee J.; Wang A. Q.; Pradhan M.; Hagen N.; Chen L.; Shen M.; Luo Z.; Xu X.; Xu Y.; Huang W.; Zheng W.; Ye Y. Heparan sulfate assists SARS-CoV-2 in cell entry and can be targeted by approved drugs in vitro. Cell Discov 2020, 6 (1), 80. 10.1038/s41421-020-00222-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva L.; Yuan S.; Yin X.; Martin-Sancho L.; Matsunaga N.; Pache L.; Burgstaller-Muehlbacher S.; De Jesus P. D.; Teriete P.; Hull M. V.; Chang M. W.; Chan J. F.; Cao J.; Poon V. K.; Herbert K. M.; Cheng K.; Nguyen T. H.; Rubanov A.; Pu Y.; Nguyen C.; Choi A.; Rathnasinghe R.; Schotsaert M.; Miorin L.; Dejosez M.; Zwaka T. P.; Sit K. Y.; Martinez-Sobrido L.; Liu W. C.; White K. M.; Chapman M. E.; Lendy E. K.; Glynne R. J.; Albrecht R.; Ruppin E.; Mesecar A. D.; Johnson J. R.; Benner C.; Sun R.; Schultz P. G.; Su A. I.; Garcia-Sastre A.; Chatterjee A. K.; Yuen K. Y.; Chanda S. K. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 antiviral drugs through large-scale compound repurposing. Nature 2020, 586 (7827), 113–119. 10.1038/s41586-020-2577-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Mendenhall M.; Deininger M. W. Imatinib is not a potent anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug. Leukemia 2020, 34 (11), 3085–3087. 10.1038/s41375-020-01045-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuvanshi R.; Bharate S. B. Recent Developments in the Use of Kinase Inhibitors for Management of Viral Infections. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 893–921. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drayman N.; DeMarco J. K.; Jones K. A.; Azizi S. A.; Froggatt H. M.; Tan K.; Maltseva N. I.; Chen S.; Nicolaescu V.; Dvorkin S.; Furlong K.; Kathayat R. S.; Firpo M. R.; Mastrodomenico V.; Bruce E. A.; Schmidt M. M.; Jedrzejczak R.; Muñoz-Alía M.; Schuster B.; Nair V.; Han K. Y.; O’Brien A.; Tomatsidou A.; Meyer B.; Vignuzzi M.; Missiakas D.; Botten J. W.; Brooke C. B.; Lee H.; Baker S. C.; Mounce B. C.; Heaton N. S.; Severson W. E.; Palmer K. E.; Dickinson B. C.; Joachimiak A.; Randall G.; Tay S. Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, 373, 931–936. 10.1126/science.abg5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCray P. B. Jr.; Pewe L.; Wohlford-Lenane C.; Hickey M.; Manzel L.; Shi L.; Netland J.; Jia H. P.; Halabi C.; Sigmund C. D.; Meyerholz D. K.; Kirby P.; Look D. C.; Perlman S. Lethal infection of K18-hACE2 mice infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol 2007, 81 (2), 813–21. 10.1128/JVI.02012-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oladunni F. S.; Park J. G.; Pino P. A.; Gonzalez O.; Akhter A.; Allue-Guardia A.; Olmo-Fontanez A.; Gautam S.; Garcia-Vilanova A.; Ye C.; Chiem K.; Headley C.; Dwivedi V.; Parodi L. M.; Alfson K. J.; Staples H. M.; Schami A.; Garcia J. I.; Whigham A.; Platt R. N. 2nd; Gazi M.; Martinez J.; Chuba C.; Earley S.; Rodriguez O. H.; Mdaki S. D.; Kavelish K. N.; Escalona R.; Hallam C. R. A.; Christie C.; Patterson J. L.; Anderson T. J. C.; Carrion R. Jr.; Dick E. J. Jr.; Hall-Ursone S.; Schlesinger L. S.; Alvarez X.; Kaushal D.; Giavedoni L. D.; Turner J.; Martinez-Sobrido L.; Torrelles J. B. Lethality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18 human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 transgenic mice. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 6122. 10.1038/s41467-020-19891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L.; Deng W.; Huang B.; Gao H.; Liu J.; Ren L.; Wei Q.; Yu P.; Xu Y.; Qi F.; Qu Y.; Li F.; Lv Q.; Wang W.; Xue J.; Gong S.; Liu M.; Wang G.; Wang S.; Song Z.; Zhao L.; Liu P.; Zhao L.; Ye F.; Wang H.; Zhou W.; Zhu N.; Zhen W.; Yu H.; Zhang X.; Guo L.; Chen L.; Wang C.; Wang Y.; Wang X.; Xiao Y.; Sun Q.; Liu H.; Zhu F.; Ma C.; Yan L.; Yang M.; Han J.; Xu W.; Tan W.; Peng X.; Jin Q.; Wu G.; Qin C. The pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in hACE2 transgenic mice. Nature 2020, 583 (7818), 830–833. 10.1038/s41586-020-2312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey W. T.; Carabelli A. M.; Jackson B.; Gupta R. K.; Thomson E. C.; Harrison E. M.; Ludden C.; Reeve R.; Rambaut A.; Peacock S. J.; Robertson D. L. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2021, 19 (7), 409–424. 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forni G.; Mantovani A. COVID-19 Commission of Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, R. m., COVID-19 vaccines: where we stand and challenges ahead. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28 (2), 626–639. 10.1038/s41418-020-00720-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klann K.; Bojkova D.; Tascher G.; Ciesek S.; Münch C.; Cinatl J. Growth Factor Receptor Signaling Inhibition Prevents SARS-CoV-2 Replication. Mol. Cell 2020, 80 (1), 164–174. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frampton J. E. Vandetanib: in medullary thyroid cancer. Drugs 2012, 72 (10), 1423–36. 10.2165/11209300-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aid M.; Busman-Sahay K.; Vidal S. J.; Maliga Z.; Bondoc S.; Starke C.; Terry M.; Jacobson C. A.; Wrijil L.; Ducat S.; Brook O. R.; Miller A. D.; Porto M.; Pellegrini K. L.; Pino M.; Hoang T. N.; Chandrashekar A.; Patel S.; Stephenson K.; Bosinger S. E.; Andersen H.; Lewis M. G.; Hecht J. L.; Sorger P. K.; Martinot A. J.; Estes J. D.; Barouch D. H. Vascular Disease and Thrombosis in SARS-CoV-2-Infected Rhesus Macaques. Cell 2020, 183 (5), 1354–1366. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.; Wang Y.; Li X.; Ren L.; Zhao J.; Hu Y.; Zhang L.; Fan G.; Xu J.; Gu X.; Cheng Z.; Yu T.; Xia J.; Wei Y.; Wu W.; Xie X.; Yin W.; Li H.; Liu M.; Xiao Y.; Gao H.; Guo L.; Xie J.; Wang G.; Jiang R.; Gao Z.; Jin Q.; Wang J.; Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395 (10223), 497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold T.; Jurinovic V.; Arnreich C.; Lipworth B. J.; Hellmuth J. C.; von Bergwelt-Baildon M.; Klein M.; Weinberger T. Elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP predict the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin Immunol 2020, 146 (1), 128–136. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y.; Ge Y.; Wu B.; Zhang W.; Wu T.; Wen T.; Liu J.; Guo X.; Huang C.; Jiao Y.; Zhu F.; Zhu B.; Cui L. Serum Cytokine and Chemokine Profile in Relation to the Severity of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. J. Infect Dis 2020, 222 (5), 746–754. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abers M. S.; Delmonte O. M.; Ricotta E. E.; Fintzi J.; Fink D. L.; de Jesus A. A. A.; Zarember K. A.; Alehashemi S.; Oikonomou V.; Desai J. V.; Canna S. W.; Shakoory B.; Dobbs K.; Imberti L.; Sottini A.; Quiros-Roldan E.; Castelli F.; Rossi C.; Brugnoni D.; Biondi A.; Bettini L. R.; D’Angio’ M.; Bonfanti P.; Castagnoli R.; Montagna D.; Licari A.; Marseglia G. L.; Gliniewicz E. F.; Shaw E.; Kahle D. E.; Rastegar A. T.; Stack M.; Myint-Hpu K.; Levinson S. L.; DiNubile M. J.; Chertow D. W.; Burbelo P. D.; Cohen J. I.; Calvo K. R.; Tsang J. S.; Su H. C.; Gallin J. I.; Kuhns D. B.; Goldbach-Mansky R.; Lionakis M. S.; Notarangelo L. D. An immune-based biomarker signature is associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients. JCI Insight 2021, 6 (1), e144455. 10.1172/jci.insight.144455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra B.; Pérez A. B.; Aguirre E.; Bracho C.; Valdés O.; Jimenez N.; Baldoquin W.; Gonzalez G.; Ortega L. M.; Montalvo M. C.; Resik S.; Alvarez D.; Guzmán M. G. Association of Early Nasopharyngeal Immune Markers With COVID-19 Clinical Outcome: Predictive Value of CCL2/MCP-1. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020, 7 (10), ofaa407. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. G.; Link H.; Baluk P.; Homer R. J.; Chapoval S.; Bhandari V.; Kang M. J.; Cohn L.; Kim Y. K.; McDonald D. M.; Elias J. A. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces remodeling and enhances TH2-mediated sensitization and inflammation in the lung. Nat. Med. 2004, 10 (10), 1095–103. 10.1038/nm1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner R. J.; Ladetto J. V.; Singh R.; Fukuda N.; Matthay M. A.; Crystal R. G. Lung overexpression of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene induces pulmonary edema. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2000, 22 (6), 657–64. 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.6.3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti H. H.; Risau W. Systemic hypoxia changes the organ-specific distribution of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95 (26), 15809–14. 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J.; Xu F.; Aondio G.; Li Y.; Fumagalli A.; Lu M.; Valmadre G.; Wei J.; Bian Y.; Canesi M.; Damiani G.; Zhang Y.; Yu D.; Chen J.; Ji X.; Sui W.; Wang B.; Wu S.; Kovacs A.; Revera M.; Wang H.; Jing X.; Zhang Y.; Chen Y.; Cao Y. Efficacy and tolerability of bevacizumab in patients with severe Covid-19. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12 (1), 814. 10.1038/s41467-021-21085-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg E.; Parent A.; Yang P. L.; Sattler M.; Liu Q.; Liu Q.; Wang J.; Meng C.; Buhrlage S. J.; Gray N.; Griffin J. D. Repurposing of Kinase Inhibitors for Treatment of COVID-19. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37 (9), 167. 10.1007/s11095-020-02851-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan T. P.; Sims A. C.; Graham R. L.; Menachery V. D.; Gralinski L. E.; Case J. B.; Leist S. R.; Pyrc K.; Feng J. Y.; Trantcheva I.; Bannister R.; Park Y.; Babusis D.; Clarke M. O.; Mackman R. L.; Spahn J. E.; Palmiotti C. A.; Siegel D.; Ray A. S.; Cihlar T.; Jordan R.; Denison M. R.; Baric R. S. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci. Transl Med. 2017, 9 (396), eaal3653. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigel J. H.; Tomashek K. M.; Dodd L. E.; Mehta A. K.; Zingman B. S.; Kalil A. C.; Hohmann E.; Chu H. Y.; Luetkemeyer A.; Kline S.; Lopez de Castilla D.; Finberg R. W.; Dierberg K.; Tapson V.; Hsieh L.; Patterson T. F.; Paredes R.; Sweeney D. A.; Short W. R.; Touloumi G.; Lye D. C.; Ohmagari N.; Oh M. D.; Ruiz-Palacios G. M.; Benfield T.; Fatkenheuer G.; Kortepeter M. G.; Atmar R. L.; Creech C. B.; Lundgren J.; Babiker A. G.; Pett S.; Neaton J. D.; Burgess T. H.; Bonnett T.; Green M.; Makowski M.; Osinusi A.; Nayak S.; Lane H. C. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Final Report. N Engl J. Med. 2020, 383, 1813–1826. 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes P. O.; Quirk D.; Furtado R. H.; Maia L. N.; Saraiva J. F.; Antunes M. O.; Kalil Filho R.; Junior V. M.; Soeiro A. M.; Tognon A. P.; Veiga V. C.; Martins P. A.; Moia D. D.F.; Sampaio B. S.; Assis S. R.L.; Soares R. V.P.; Piano L. P.A.; Castilho K.; Momesso R. G.R.A.P.; Monfardini F.; Guimaraes H. P.; Ponce de Leon D.; Dulcine M.; Pinheiro M. R.T.; Gunay L. M.; Deuring J. J.; Rizzo L. V.; Koncz T.; Berwanger O. Tofacitinib in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19 Pneumonia. N Engl J. Med. 2021, 385 (5), 406–415. 10.1056/NEJMoa2101643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazopoulou E.; Poulakou G.; Milionis H.; Metallidis S.; Adamis G.; Tsiakos K.; Fragkou A.; Rapti A.; Damoulari C.; Fantoni M.; Kalomenidis I.; Chrysos G.; Angheben A.; Kainis I.; Alexiou Z.; Castelli F.; Serino F. S.; Tsilika M.; Bakakos P.; Nicastri E.; Tzavara V.; Kostis E.; Dagna L.; Koufargyris P.; Dimakou K.; Savvanis S.; Tzatzagou G.; Chini M.; Cavalli G.; Bassetti M.; Katrini K.; Kotsis V.; Tsoukalas G.; Selmi C.; Bliziotis I.; Samarkos M.; Doumas M.; Ktena S.; Masgala A.; Papanikolaou I.; Kosmidou M.; Myrodia D. M.; Argyraki A.; Cardellino C. S.; Koliakou K.; Katsigianni E. I.; Rapti V.; Giannitsioti E.; Cingolani A.; Micha S.; Akinosoglou K.; Liatsis-Douvitsas O.; Symbardi S.; Gatselis N.; Mouktaroudi M.; Ippolito G.; Florou E.; Kotsaki A.; Netea M. G.; Eugen-Olsen J.; Kyprianou M.; Panagopoulos P.; Dalekos G. N.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis E. J. Author Correction: Early treatment of COVID-19 with anakinra guided by soluble urokinase plasminogen receptor plasma levels: a double-blind, randomized controlled phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2021, 27 (10), 1850. 10.1038/s41591-021-01569-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drayman N.; DeMarco J. K.; Jones K. A.; Azizi S.-A.; Froggatt H. M.; Tan K.; Maltseva N. I.; Chen S.; Nicolaescu V.; Dvorkin S.; Furlong K.; Kathayat R. S.; Firpo M. R.; Mastrodomenico V.; Bruce E. A.; Schmidt M. M.; Jedrzejczak R.; Muñoz-Alía M. Á.; Schuster B.; Nair V.; Han K.-y.; O’Brien A.; Tomatsidou A.; Meyer B.; Vignuzzi M.; Missiakas D.; Botten J. W.; Brooke C. B.; Lee H.; Baker S. C.; Mounce B. C.; Heaton N. S.; Severson W. E.; Palmer K. E.; Dickinson B. C.; Joachimiak A.; Randall G.; Tay S. Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, 373 (6557), 931–936. 10.1126/science.abg5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P.; Oliver S.; Kennedy S. J.; Partridge E.; Hutchison M.; Clarke D.; Giles P. Pharmacokinetics of vandetanib: three phase I studies in healthy subjects. Clin Ther 2012, 34 (1), 221–37. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong W.; Doroshow J. H.; Kummar S. United States Food and Drug Administration approved oral kinase inhibitors for the treatment of malignancies. Curr. Probl Cancer 2013, 37 (3), 110–44. 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair A. B.; Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic Clin Pharm. 2016, 7 (2), 27–31. 10.4103/0976-0105.177703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prete A.; Falcone M.; Bottici V.; Giani C.; Tiseo G.; Agate L.; Matrone A.; Cappagli V.; Valerio L.; Lorusso L.; Minaldi E.; Molinaro E.; Elisei R. Thyroid cancer and COVID-19: experience at one single thyroid disease referral center. Endocrine 2021, 72 (2), 332–339. 10.1007/s12020-021-02650-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl A. C.; Fritch E. J.; Lane T. R.; Tse L. V.; Yount B. L.; Sacramento C. Q.; Fintelman-Rodrigues N.; Tavella T. A.; Maranhão Costa F. T.; Weston S.; Logue J.; Frieman M.; Premkumar L.; Pearce K. H.; Hurst B. L.; Andrade C. H.; Levi J. A.; Johnson N. J.; Kisthardt S. C.; Scholle F.; Souza T. M. L.; Moorman N. J.; Baric R. S.; Madrid P. B.; Ekins S. Repurposing the Ebola and Marburg Virus Inhibitors Tilorone, Quinacrine, and Pyronaridine:. ACS Omega 2021, 6 (11), 7454–7468. 10.1021/acsomega.0c05996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y. J.; Okuda K.; Edwards C. E.; Martinez D. R.; Asakura T.; Dinnon K. H. 3rd; Kato T.; Lee R. E.; Yount B. L.; Mascenik T. M.; Chen G.; Olivier K. N.; Ghio A.; Tse L. V.; Leist S. R.; Gralinski L. E.; Schafer A.; Dang H.; Gilmore R.; Nakano S.; Sun L.; Fulcher M. L.; Livraghi-Butrico A.; Nicely N. I.; Cameron M.; Cameron C.; Kelvin D. J.; de Silva A.; Margolis D. M.; Markmann A.; Bartelt L.; Zumwalt R.; Martinez F. J.; Salvatore S. P.; Borczuk A.; Tata P. R.; Sontake V.; Kimple A.; Jaspers I.; O’Neal W. K.; Randell S. H.; Boucher R. C.; Baric R. S. SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics Reveals a Variable Infection Gradient in the Respiratory Tract. Cell 2020, 182 (2), 429–446. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.; Dickmander R. J.; Bayati A.; Taft-Benz S. A.; Smith J. L.; Wells C. I.; Madden E. A.; Brown J. W.; Lenarcic E. M.; Yount B. L.; Chang E.; Axtman A. D.; Baric R. S.; Heise M. T.; McPherson P. S.; Moorman N. J.; Willson T. M.. Host kinase CSNK2 is a target for inhibition of pathogenic β-coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2022, 10.1101/2022.01.03.474779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spearman C. The method of ‘right and wrong cases’ (‘constant stimuli’) without Gauss’s formulae. Brit J. Psychol 1908, 2, 227–242. 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1908.tb00176.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kärber G. Beitrag zur kollektiven behandlung pharmakologischer reihenversuche. Archiv f Experiment Pathol u Pharmakol 1931, 162, 480–483. 10.1007/BF01863914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl A. C.; Gomes G. F.; Damasceno S.; Godoy A. S.; Noske G. D.; Nakamura A. M.; Gawriljuk V. O.; Fernandes R. S.; Monakhova N.; Riabova O.; Lane T. R.; Makarov V.; Veras F. P.; Batah S. S.; Fabro A. T.; Oliva G.; Cunha F. Q.; Alves-Filho J. C.; Cunha T. M.; Ekins S. Pyronaridine Protects against SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Mouse. ACS Infect Dis 2022, 8, 1147–1160. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oladunni F. S.; Park J. G.; Pino P. A.; Gonzalez O.; Akhter A.; Allué-Guardia A.; Olmo-Fontánez A.; Gautam S.; Garcia-Vilanova A.; Ye C.; Chiem K.; Headley C.; Dwivedi V.; Parodi L. M.; Alfson K. J.; Staples H. M.; Schami A.; Garcia J. I.; Whigham A.; Platt R. N.; Gazi M.; Martinez J.; Chuba C.; Earley S.; Rodriguez O. H.; Mdaki S. D.; Kavelish K. N.; Escalona R.; Hallam C. R. A.; Christie C.; Patterson J. L.; Anderson T. J. C.; Carrion R.; Dick E. J.; Hall-Ursone S.; Schlesinger L. S.; Alvarez X.; Kaushal D.; Giavedoni L. D.; Turner J.; Martinez-Sobrido L.; Torrelles J. B. Lethality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18 human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 transgenic mice. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 6122. 10.1038/s41467-020-19891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L.; Deng W.; Huang B.; Gao H.; Liu J.; Ren L.; Wei Q.; Yu P.; Xu Y.; Qi F.; Qu Y.; Li F.; Lv Q.; Wang W.; Xue J.; Gong S.; Liu M.; Wang G.; Wang S.; Song Z.; Zhao L.; Liu P.; Zhao L.; Ye F.; Wang H.; Zhou W.; Zhu N.; Zhen W.; Yu H.; Zhang X.; Guo L.; Chen L.; Wang C.; Wang Y.; Wang X.; Xiao Y.; Sun Q.; Liu H.; Zhu F.; Ma C.; Yan L.; Yang M.; Han J.; Xu W.; Tan W.; Peng X.; Jin Q.; Wu G.; Qin C. The pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in hACE2 transgenic mice. Nature 2020, 583 (7818), 830–833. 10.1038/s41586-020-2312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yinda C. K.; Port J. R.; Bushmaker T.; Offei Owusu I.; Purushotham J. N.; Avanzato V. A.; Fischer R. J.; Schulz J. E.; Holbrook M. G.; Hebner M. J.; Rosenke R.; Thomas T.; Marzi A.; Best S. M.; de Wit E.; Shaia C.; van Doremalen N.; Munster V. J. K18-hACE2 mice develop respiratory disease resembling severe COVID-19. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17 (1), e1009195 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce V. M.; Costoya J. A. SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18-ACE2 transgenic mice replicates human pulmonary disease in COVID-19. Cell Mol. Immunol 2021, 18 (3), 513–514. 10.1038/s41423-020-00616-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau G. B.; Burgess S. L.; Sturek J. M.; Donlan A. N.; Petri W. A.; Mann B. J. Evaluation of K18-. Am. J. Trop Med. Hyg 2020, 103 (3), 1215–1219. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler E. S.; Bailey A. L.; Kafai N. M.; Nair S.; McCune B. T.; Yu J.; Fox J. M.; Chen R. E.; Earnest J. T.; Keeler S. P.; Ritter J. H.; Kang L. I.; Dort S.; Robichaud A.; Head R.; Holtzman M. J.; Diamond M. S. Publisher Correction: SARS-CoV-2 infection of human ACE2-transgenic mice causes severe lung inflammation and impaired function. Nat. Immunol 2020, 21 (11), 1470. 10.1038/s41590-020-0794-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Wong L. R.; Li K.; Verma A. K.; Ortiz M. E.; Wohlford-Lenane C.; Leidinger M. R.; Knudson C. M.; Meyerholz D. K.; McCray P. B.; Perlman S. COVID-19 treatments and pathogenesis including anosmia in K18-hACE2 mice. Nature 2021, 589 (7843), 603–607. 10.1038/s41586-020-2943-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia C. C. W.; Hyde D. M.; Ochs M.; Weibel E. R. An official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am. J. Respir Crit Care Med. 2010, 181 (4), 394–418. 10.1164/rccm.200809-1522ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.