Abstract

Simple Summary

A significant proportion of families with a clinical suggestion of Lynch syndrome and screened for the known MMR genes remain without a molecular diagnosis. These patients, who generally show a suggestive family pedigree or early-onset tumors with MMR deficiency and no detectable germline variants, are referred to as having Lynch-like syndrome. To investigate underlying and potentially predisposing variants related to Lynch-like syndrome, we performed whole-exome sequencing in patients with clinical criteria for Lynch syndrome, MMR deficiency and without germline variants. This approach allowed for the identification of new variants potentially associated with Lynch-like syndrome, providing new clues to explain the familial predisposition to Lynch syndrome-related tumors in these patients, which could lead to new screening strategies for the identification of families at risk of developing cancer.

Abstract

Lynch syndrome (LS) is the most common hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC) syndrome, characterized by germline pathogenic variants in mismatch repair (MMR)-related genes that lead to microsatellite instability. Patients who meet the clinical criteria for LS and MMR deficiency and without any identified germline pathogenic variants are frequently considered to have Lynch-like syndrome (LLS). These patients have a higher risk of CRC and extracolonic tumors, and little is known about their underlying genetic causes. We investigated the germline spectrum of LLS patients through whole-exome sequencing (WES). A total of 20 unrelated patients with MMR deficiency who met the clinical criteria for LS and had no germline variant were subjected to germline WES. Variant classification was performed according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria. Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants were identified in 35% of patients in known cancer genes such as MUTYH and ATM. Besides this, rare and potentially pathogenic variants were identified in the DNA repair gene POLN and other cancer-related genes such as PPARG, CTC1, DCC and ALPK1. Our study demonstrates the germline mutational status of LLS patients, a population at high risk of colorectal cancer.

Keywords: hereditary colorectal cancer, Lynch-like syndrome, cancer predisposition

1. Introduction

Hereditary cancer represents an important portion of the global cancer burden [1], but only a minority of such cases are attributed to known germline pathogenic variants and/or cancer-predisposing syndromes [2]. Lynch syndrome (LS) is the most common predisposing syndrome associated with colorectal cancer (CRC), accompanied by an increased risk of extracolonic cancers, such as endometrium, stomach, ovary, pancreas, ureter or renal pelvis, biliary tract, brain (mainly glioblastoma) and small bowel [3]. According to the currently accepted consensus, LS is characterized by germline variants in genes related to DNA mismatch repair (MMR), mainly the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 genes, which lead to MMR deficiency and consequent tumors with microsatellite instability (MSI) [3]. Besides this, EPCAM deletions are also a known cause of Lynch syndrome [3].

LS patients generally present fulfilling the Amsterdam criteria or one of the revised Bethesda guidelines [3] and with a pathogenic germline variant in MMR genes. However, 30% of the families with a clinical suggestion of LS and screened for the common MMR genes remain without a molecular diagnosis [3]. This subset of patients, who generally show a suggestive family pedigree or early-onset tumors with MMR deficiency and no detectable germline mutation or hypermethylation in the MMR genes, are referred to as having Lynch-like syndrome (LLS) [4]. Although the clinicopathological features of LLS patients appear to differ from those of LS patients [5] and resemble those of patients with sporadic tumors [6], the risk of colorectal cancer in these patients and their families is reported to be higher than that of sporadic tumors [7]. Furthermore, patients with LLS are often diagnosed at a younger age than patients with sporadic tumors [6,8]. This indicates, at least in part, a hereditary component of LLS.

A previous study from our group [9] evaluated 323 probands with a family history suggestive of LS. Among those, 134 tumors were MMR-deficient. Genetic testing was performed on 127 of them, and 65 (51%) did not have a pathogenic alteration at the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, or EPCAM gene, even though their tumors had MSI and loss of expression of either MMR protein, as indicated by IHC.

The underlying germline mutation spectrum of LLS is poorly explored. Some studies reported the presence of biallelic germline variants in the MUTYH gene in LLS cases [10,11], and MUTYH-associated polyposis can overlap with the LS phenotype by somatic inactivation of MMR genes [10]. Beyond this, LLS patients carrying POLE and POLD1 germline variants have also been identified [12,13]. The presence of germline variants in DNA repair genes, such as MCM8, MCM9, WRN, MCPH1, BARD1, REV3L, EXO1, POLD1, RFC1, RPA1 and MLH3, has additionally been reported in patients with LLS [8,13,14].

In that context, we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) in patients with an MMR deficiency without germline variants and identified new variants possibly associated with LLS development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

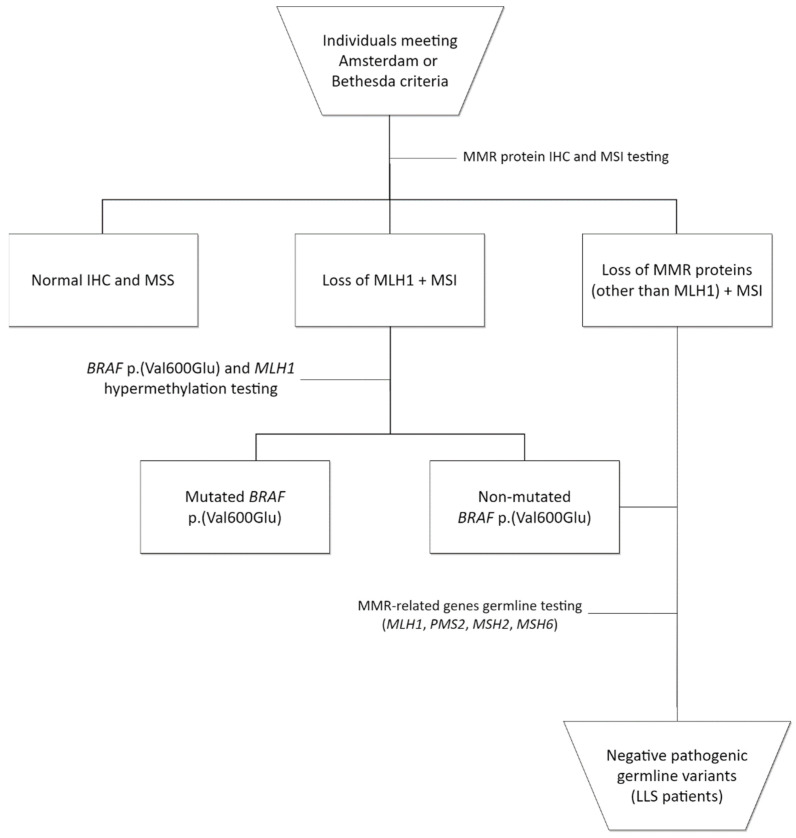

Twenty patients identified at the Oncogenetics Department of Barretos Cancer Hospital were included in this study [15]. Patients were included after signing an informed consent form, and the study was approved by the Barretos Cancer Hospital Institutional Review Board (protocol CAAE: 56164716.9.0000.5437). The patient selection followed the Lynch syndrome strategy as previously reported [9]. Briefly, samples from patients meeting the Amsterdam or Bethesda criteria underwent immunohistochemistry (IHC) for the four MMR-related proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6) and microsatellite instability (MSI) analysis. Patients with MMR-deficient tumors for PMS2, MSH2 or MSH6 underwent germline genetic testing for the respective gene. Meanwhile, patients with MLH1-deficient tumors were subjected to germline genetic testing only if they had a wild-type result in BRAF p. (Val600Glu) (BRAF V600E) analysis, regardless of their MLH1 hypermethylation status. Patients with an absence of germline variants in any of the MMR-related genes and with loss of MMR protein expression were included in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Lynch-like syndrome (LLS) patients’ identification and inclusion. IHC: immunohistochemistry; MSI: microsatellite instability.

2.2. DNA Isolation and Whole-Exome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using the QIAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit for the QIAcub automated platform (QIAGEN, Hilde, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA quantity and quality were assessed by a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). WES was conducted by SOPHiA™ genetics using an Illumina NovaSeq sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with a Whole Exome Solution Kit (version 1), including 203,058 target regions and 40,907,213 bp in 19,682 genes. The mean coverage of sequencing was 150× (99.6% above 10×, 99.4% above 20×, 99.3% above 20 and 30× and 99.3% above 40× and 50×).

2.3. Sequence Quality Control, Alignment and Variant Calling

Determination of the quality of reads, alignment and variant calling were performed as previously described [16]. The quality of reads was accessed by FASTQC [17], trimmed by Cutadapt [18] and mapped against the human genome reference (build GRCh37/hg19) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA, version 0.7.17) [19]. Postprocessing alignment was performed using Picard [20] for read duplication removal, and the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) [21] was used for quality score recalibration. Variant calling was performed by the HaplotypeCaller [22].

2.4. Variant Annotation and Classification

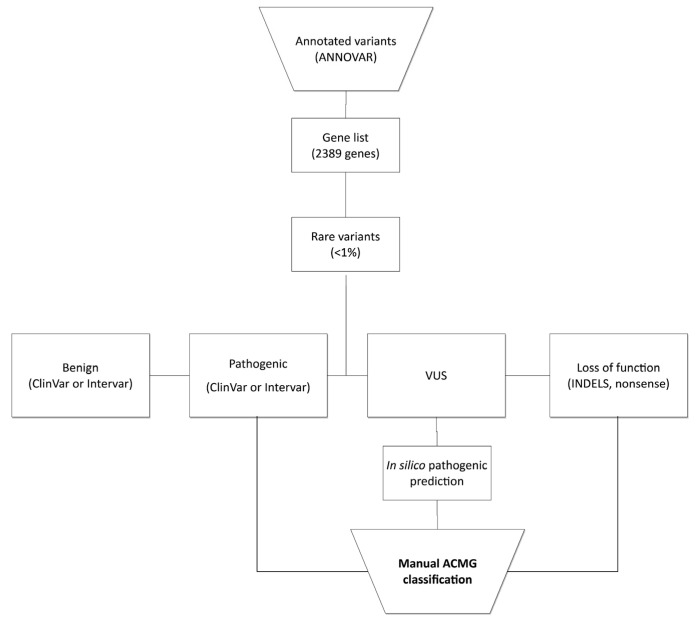

Variant annotation was performed by ANOVA. We analyzed a selected set of 2389 genes [16] (Supplementary Table S1), built from cancer-related genes (COSMIC [23], UniProt [24] and DISEASES databases [25]), hereditary syndrome cancer-related genes (extracted from commercial panels, GeneCards [26] and the Genetics Home Reference database [27]) and DNA repair genes (from Das and colleagues’ study [28]). We developed an analytical pipeline to filter variants for manual classification (Figure 2). Briefly, variants were filtered to remove those with fewer than 30 reads and a variant allele frequency below 25%. Populational databases (ABraOM and gnomAD) were used to remove variants with a minor allele frequency >1%. Pathogenic variants (defined by ClinVar or Intervar), loss-of-function variants (indels and nonsense variants) and variants of uncertain significance (VUS) with an in silico pathogenic score (REVEL >0.7 or M-CAP >0.025 for missense variants and Human Splicing Finder (HSF) for splicing variants) were selected for manual classification. Two independent researchers (the first and last authors of this study) manually classified the selected variants as benign or likely benign (I or II), VUS (III), likely pathogenic or pathogenic (IV or V) following ACMG criteria [29]. All selected variants were subjected to visual exploration in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) [30]. Variants classified as IV or V were confirmed by bidirectional Sanger sequencing.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of decision process for variant prioritization.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (v. 23) and R (v. 3.6.1) software. Descriptive data were expressed by a number, percentage, mean and standard deviation. Age comparisons between groups were performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Numbers of tumors were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare potentially pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants and tumor features.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

We included in our study a total of 20 patients with MMR deficiency but without pathogenic germline variants in the MMR-associated genes (Table 1). Most patients were female (60%), and the mean age of the first diagnosed tumor was 48 years (SD = 7.7). CRC was the first diagnosed tumor in 75% of patients (n = 15), and otherwise, the extracolonic tumors first diagnosed were endometrial (n = 2), ovarian (n = 2) and gastric (n = 1). Five patients were diagnosed with a second tumor; those included CRC, endometrium, breast and non-melanoma skin (Table 1). Amsterdam clinical criteria were fulfilled by 25% of patients. A total of 90% of patients had a family history of cancer, and 75% had LS-related tumors in the family.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with Lynch-like syndrome (LLS).

| Characteristics (n = 20) | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 12 | (60) |

| Male | 8 | (40) |

| Survival status | ||

| Followed-up | 19 | (95) |

| Deceased | 1 | (5) |

| Mean age of first diagnosed tumor (SD) | 48.2 (7.7) | |

| First diagnosed tumor | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 15 | (75) |

| Endometrium | 2 | (10) |

| Ovary | 2 | (10) |

| Stomach | 1 | (5) |

| Mean age of second diagnosed tumor (SD) | 59.2 (7) | |

| Second diagnosed tumor | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 1 | (5) |

| Endometrium | 2 | (10) |

| Breast | 1 | (5) |

| Non-melanoma skin | 1 | (5) |

| Clinical criteria | ||

| Amsterdam | 5 | (25) |

| Bethesda | 8 | (40) |

| Revised Bethesda | 7 | (35) |

SD: standard deviation.

3.2. Germline Variants’ Profile

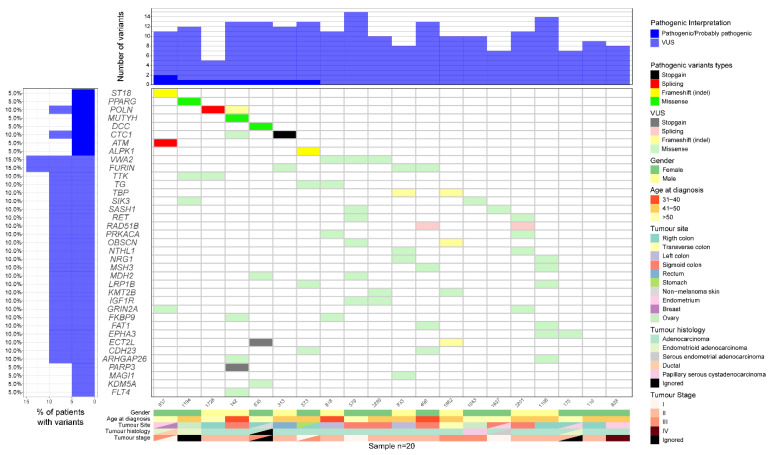

After filtering out variants, we found a total of 319 germline variants for manual prioritization on 2389 analyzed genes. Manual classification using ACMG criteria resulted in 33.5% of variants being classified as benign or likely benign (107/319), 63.9% variants of uncertain significance (204/319, Supplementary Table S2) and 2.5% pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (8/319). Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants were present in 35% of patients (7/20, Figure 3 and Table 2). These patients with pathogenic variants did not differ from patients without pathogenic variants concerning the age at first diagnosed tumor (mean age of 48.3 vs. 48.2, p = 0.974), number of family tumors (mean number of 3.7 vs. 6.7 tumors, p = 0.193), tumor grade (p = 0.650) or tumor stage (p = 0.854).

Figure 3.

Representative plot of patients carrying pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants (genes on the top) and VUS (only for genes with over 5% VUS in our patients with Lynch-like syndrome).

Table 2.

Pathogenic (V) or likely pathogenic (IV) variants identified in our patients with Lynch-like syndrome.

| ID Case | Gene | Pathogenic Variant | REVEL | AF | (Class) 1 | Tumor Site |

Age 2 | Criteria Fulfilled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1194 | PPARG |

NM_015869.5:c.1230C > A p.(Ser410Arg) |

0.767 | 1.60 × 10−5 | (IV) | ovary | 44 | Bethesda * |

| 142 | MUTYH |

NM_001128425.2:c.1187G > A p. (Gly396Asp) |

0.954 | 3.00 × 10−3 | (V) | colorectal | 39 | Bethesda |

| 1728 | POLN |

NC_000004.11(NM_181808.2):c.1375-2A > G splicing variant |

- | 4.07 × 10−6 | (V) | colorectal | 57 | Bethesda * |

| 313 | CTC1 |

NM_025099.6:c.19C > T p. (Gln7Ter) |

- | 1.68 × 10−5 | (V) | colorectal | 48 | Bethesda * |

| 573 | ALPK1 |

NM_001102406.2:c.3428_3431del p. (Asn1143ThrfsTer5) |

- | - | (IV) | stomach colorectal |

44 49 |

Bethesda |

| 635 | DCC |

NM_005215.4:c.1861G > A p. (Val621Met) |

0.303 | 2.00 × 10−4 | (IV) | colorectal non-melanoma skin |

50 56 |

Bethesda * |

| 837 | ATM |

NC_000011.9(NM_000051.3):c.3993 + 1G > A splicing variant |

- | 1.60 × 10−5 | (V) | endometrium breast |

53 58 |

Bethesda * |

| ST18 |

NM_014682.2:c.2093del p. (Lys698SerfsTer24) |

- | - | (IV) |

Af: allele frequency on gnomAD; ACMG: American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics criteria; 1 Variant classification according to ACMG criteria; 2 Age at first diagnosed tumor; * Revised Bethesda Guidelines.

3.3. Germline Variants’ Classification

Variants classified as pathogenic and likely pathogenic are shown in Table 2. A heterozygous pathogenic missense variant in the MUTYH gene (NM_001128425.2:c.1187G > A p.(Gly396Asp), Table 2) was found in a patient with CRC who was diagnosed at age 39 (ID 142, Table 2) and had a familial history of CRC of paternal lineage and esophageal cancer of maternal lineage (Supplementary Table S2 and Figure S1). The patient’s tumor showed loss of MLH1/PMS2 expression and isolated loss of MSH6 expression. This patient also showed a heterozygous nonsense variant at the PARP3 gene that was classified as VUS, as well as 11 additional variants classified as VUS (Supplementary Table S3).

A heterozygous pathogenic splicing variant was found on a DNA polymerase type-A family member, POLN (NC_000004.11(NM_181808.2):c.1375-2A > G) on patient ID 1728 (Table 2). In addition, a VUS in another DNA repair gene (ERCC5), as well as variants on the E2F7, GRHL2 and TTK genes (Supplementary Table S3), were identified in the same patient. This patient had CRC diagnosed at age 57, with loss of PMS2 expression and weak MLH1 expression, but did not show a history of tumors in the family (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Figure S2).

A CTC1 heterozygous pathogenic nonsense variant (NM_025099.6:c.19C > T p. (Gln7Ter), Table 2) was found in a patient (ID 313) who had CRC with isolated loss of MSH6, as was diagnosed at age 48; the patient had no LS-related tumors in the family (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Figure S3). Yet, this patient also showed a VUS with a high score for pathogenic prediction in the RBL1 gene and a truncating VUS in the PCM1 gene, which are both cancer-related genes (Supplementary Table S3). Further to this, we classified nine variants as VUS in several other cancer-related genes (Supplementary Table S3).

The DCC gene showed a heterozygous likely pathogenic missense variant possibly affecting the splice site at the end of exon 11 (NM_005215.4:c.1861G > A p.(Val621Met), Table 2) that we classified as likely pathogenic. The patient carrying this variant (ID 635) had CRC with loss of PMS2/MSH6 expression at age 50 and a nonmelanoma skin tumor diagnosed at age 56 (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S4). The family of the patient did not show a history of tumors (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Figure S4). In addition to the likely pathogenic variant on the DCC gene, we also identified a truncating VUS in the ECT2L gene, along with 11 variants classified as VUS in cancer-related genes (Supplementary Table S3).

3.4. Variants in Patients with Loss of MLH1 or PMS2

We identified 10 patients with tumors not expressing MLH1 or PMS2, six of whom had hypermethylation in the MLH1 promoter region. With one inconclusive exception, all MLH1-methylated cases were BRAF p. (Val600Glu) wild-type. We did not find any difference between MLH1-methylated cases and MLH1-nonmethylated cases with an MLH1 or PMS2 expression deficiency regarding the mean age at first diagnosis (mean age of 48 vs. 55.1, p = 0.591), number of family tumors (mean number of 4.8 vs. 8 tumors, p = 0.118) or presence of potentially pathogenic variants (50% vs. 25%, p = 0.571).

Potentially pathogenic variants were identified in three MLH1-hypermethylation cases. A likely pathogenic missense variant at the PPARG gene (NM_015869.5:c.1230C > A p.(Ser410Arg), Table 2) was found in a patient (ID 1194) with an ovarian tumor diagnosed at age 44. This tumor showed MSI without loss of MMR proteins and methylation of the MLH1 gene. The mother of the patient was diagnosed with meningioma at age 71, and the paternal grandfather had a gastric tumor (Supplementary Table S2 and Figure S5). We also identified 11 VUS in this patient, including a missense variant on the FANCA gene, which is involved in DNA repair damage (Supplementary Table S3).

Another likely pathogenic frameshift variant was identified in the ALPK1 gene (NM_001102406.2:c.3428_3431del p. (Asn1143ThrfsTer5), Table 2). This variant was identified in a patient (ID 573) with a gastric tumor diagnosed at age 44 and CRC diagnosed at age 49 with loss of MLH1/PMS2 expression and methylated MLH1. The patient’s brother had a pharynx tumor, and her paternal lineage developed tumors of the breast (paternal aunt) and stomach (paternal grandmother, Supplementary Table S2 and Figure S6). We also identified 12 VUS in this patient, including a missense mutation with a high score of pathogenic prediction in the EPHA5 gene and three truncating VUS in the NBPF3, NINL and RETN genes (Supplementary Table S3).

Finally, the other patient with an MLH1 methylated tumor in which pathogenic variants were identified was ID 837. In this patient, with an endometrial tumor diagnosed at age 53 and loss of MLH1/PMS2 expression, we identified two variants classified as pathogenic and likely pathogenic in the ATM and ST18 genes, respectively. This patient was further diagnosed with breast cancer at age 58. The ATM gene had a splicing variant (NC_000011.9(NM_000051.3):c.3993 + 1G > A) classified as pathogenic, and the ST18 gene had a frameshift variant (NM_014682.2:c.2093del p. (Lys698SerfsTer24), Table 2) classified as likely pathogenic (Table 2). In addition, this patient harbored 9 VUS (Supplementary Table S3), including two missense variants with high scores of pathogenic predictions in the RPN1 and TMC8 genes, respectively. The patient’s sister had a breast tumor at age 56, and her maternal lineage showed tumors of the throat, prostate and intestine (Supplementary Table S2 and Figure S7).

In addition to the three MLH1-methylated cases harboring potentially pathogenic germline variants, we also had three MLH1-methylated cases without. A patient with CRC with loss of MLH1/PMS2 expression diagnosed at age 41 (ID 1196) and a family history of pancreatic tumor (father, Supplementary Table S2) was identified as carrying VUS in the MMR-related MSH3 gene (NM_002439.5:c.1777C > T p. (Arg593Trp) and a CHEK2 VUS (NM_007194.4:c.1427C > T p. (Thr476Met), Supplementary Table S3). We also identified a high score of pathogenic prediction for missense variants in the EPHA3, LRP1B and RAB5A genes in this patient (Supplementary Table S3). Another MLH1-methylated case was identified in a patient with an ovarian tumor at age 56 and CRC with loss of MLH1/PMS2 expression at age 60 (ID 1043), and she had a family history of LS-related tumors (Supplementary Table S2). This patient was identified to have a missense VUS with a high score of pathogenic prediction in the ERCC6L2 and SIK3 cancer-related genes in addition to VUS in the SMAD6 CRC-related gene (Supplementary Table S3). A third MLH1-methylated case carrying only VUS was observed in a patient (ID 828, Supplementary Table S3) diagnosed at age 46 with an endometrial tumor, with loss of MLH1/PMS2 expression and a family history of endometrial, prostate and unidentified tumors (mother, father and paternal uncle, respectively, Supplementary Table S2).

3.5. Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS)

VUS were found in several key genes (Supplementary Table S3), with 43 genes harboring either a high score of pathogenic prediction (REVEL score > 0.7) or truncation variants. In addition to the VUS in the MMR-related MSH3 gene on patient ID 1196, we found a high pathogenic score prediction or truncation VUS on DNA repair genes CCNH (ID 116), TP53BP1 (ID 175), RAD51B (IDs 2201 and 496), NTHL1 (IDs 2201 and 933), POLH (ID 496) and RAD54L (ID 579, Supplementary Table S3).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we performed WES on germline DNA from patients with MSI positivity and loss of MMR protein expression but without germline MMR pathogenic variants. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore germline identification through WES for LLS patients in a Brazilian population. WES technologies have become accessible and have been integrated into clinical practice in recent years [31]. Although this approach has several challenges, such as data management, incidental findings and variant prioritization and/or interpretation [32], WES can be useful to uncover the underlying genetic basis of cancer predisposition [33,34].

Through our WES approach, we identified 35% of LLS patients harboring potentially pathogenic variants in cancer-related, hereditary or DNA repair genes. Previous studies that investigated the germline basis for LLS identified a wide range of variants with the potential for cancer predisposition [10,14,35]. Using WES, Xicola and colleagues identified a similar frequency of potentially pathogenic variants in DNA repair-related genes (36.4%) to that found in the current study [8]. Other potentially pathogenic germline variants have been linked to LLS patients, such as variants in POLE [35], MCM8 [14] and MUTYH [10,36].

An inherited biallelic mutation at the MUTYH gene is related to MUTYH-associated polyposis [37], and the missense MUTYH p. (Gly396Asp) variant that we found is related to abnormal MUTYH protein activity [38]. MUTYH monoallelic variant carriers had an approximately two-fold increased risk of colorectal cancer [39] and showed an increased risk of gastric, liver and endometrial tumors (3.34, 3.09 and 2.33, respectively) [40]. The prevalence of MUTYH monoallelic variants in LLS has previously been reported as 3.6% in LLS patients [10], similar to the frequency observed in our study. Furthermore, screening for MUTYH variants has been proposed for patients with MMR deficiency and the absence of MMR-related germline variants [10].

The polymerase POLN gene is involved in DNA cross-link repair and homologous recombination [41]. The variant present in our cohort is supposed to affect the splicing of POLN exon 12. The frequency of POLN-inactivating variants shown as increased in patients with pancreatic tumors compared to controls [42] and has a 6.9-fold increased risk of prostate tumors in the Chinese population [43]. An inactivating variant of the POLN gene has also been found in ovarian cancer patients, although the frequency did not differ significantly from controls [44]. Another variant affecting splicing sites was found in the DCC gene, which encodes a transmembrane protein involved in axonal guidance of neuronal growth and is frequently deleted or downregulated in CRC [45].

The CTC1 gene encodes a component of the CST complex that plays a role in telomeric integrity [46]. Variants in the CTC1 gene are associated with Coats plus syndrome [47], as well as cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts [46]. Heterozygous deleterious germline variants at the CTC1 gene have been found in myelodysplastic syndrome [48], and the nonsense mutation that we found here has been found in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia [49].

Several studies do not include MLH1-methylated cases in LLS germline investigations [8,14]. Yet, the presence of tumors with MLH1 methylation does not exclude the presence of germline variants in LS patients [9]; we identified the presence of pathogenic variants in 50% of our MLH1-methylated cases. Interestingly, there were two pathogenic variants not previously reported in the literature, which were identified in MLH1-methylated cases from our study. These were a frameshift variant on ALPK1, a gene with downregulated expression in lung and colorectal tumors [50], and a frameshift variant on ST18, a gene with tumor-suppressing activity in breast tumors [51]. Another pathogenic variant identified in MLH1-methylated cases was a missense variant in the PPARG gene, which is a member of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor subfamily, missense variants of which have been found in a family with dyslipidemia and colonic polyp formation [52] and patients with endometrial carcinoma [53]. Additionally, another pathogenic variant identified in MLH1-methylated cases was a splicing ATM variant shown in patients with ataxia-telangiectasia [54], breast [55] and pancreatic [56] tumors.

Despite the interesting and novel findings, our work has certain limitations. The restricted analysis of a prebuilt gene set limited our work, meaning we could not engage in variant discovery outside this subset of genes. Additionally, the intrinsic restriction of WES technology meant we could not investigate intronic variants or regulatory regions outside exon sequences. Nor could we investigate tumor tissue mutations beyond the BRAF p. (Val600Glu) status, which would have provided further information on the loss of heterozygosity and pathogenicity evidence, as well as the possibility of MMR biallelic mutations. Finally, the small number of patients evaluated impacted the statistical significance of the germline findings and clinical associations. Yet, despite these limitations, this study makes an important contribution to the field, given that the Brazilian population is relatively understudied. Besides this, we identified promising candidate genes involved in DNA repair, apoptosis and metabolism, among other pathways, thus providing novel information on potential LLS-related pathways and an excellent premise for future studies and the discovery/validation of novel associations between genes and diseases.

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the germline basis for Lynch-like syndrome in Brazilian patients through WES. We reported the presence of potentially pathogenic variants that could explain the familial predisposition to Lynch syndrome-related tumors without a germline basis of MMR deficiency, including cases with MLH1 methylation, which could support new screening strategies for the identification of families at risk of developing cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank the medical doctors Luis Gustavo Romagnolo and Maximiliano Cadamuro from the Oncogenetics Department of Barretos Cancer Hospital for their patient care. We thank certain staff members of the Molecular Diagnostic Center of Barretos Cancer Hospital, namely André Escremin de Paula, Gustavo Noriz Berardinelli and Gabriela Carvalho Fernandes, for processing the patients’ samples. Finally, we thank the entire hereditary cancer research team and the staff of the Molecular Oncology Research Center of Barretos Cancer Hospital for their assistance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers14174233/s1, Figures S1–S7: Representative pedigrees of the families of patients carrying putative pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants; Table S1: List of genes analyzed in the present study; Table S2: Family history and pathogenic (V) or likely pathogenic (IV) variants identified in our patients with Lynch-like syndrome; Table S3: List of VUS classified by ACMG manual curation in our patients with Lynch-like syndrome.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.I.P.; methodology, E.I.P. and E.S.A.; software, W.S. and. E.S.A.; validation, E.I.P. and F.A.O.G.; formal analysis, W.S. and E.S.A.; investigation, W.S., E.S.A. and. E.I.P.; resources, N.C., C.S.S., H.C.R.G. and E.S.A.; data curation, W.S., N.C., C.S.S. and E.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S.; writing—review and editing, W.S. and E.I.P.; visualization, W.S.; supervision, E.I.P.; project administration, E.I.P., M.E.M. and R.M.R.; funding acquisition, E.I.P., M.E.M. and R.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was reviewed and approved by Barretos Cancer Hospital’s Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 56164716.9.0000.5437). All research was performed according to the Brazilian CEP/CONEP system’s regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Variants classified will be deposited in the ClinVar database. Data that support the findings are not readily available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Requests for data access should be directed to the corresponding author, Edenir Inez Palmero.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Programa Nacional de Apoio à Atenção Oncológica (PRONON) from the Ministério da Saúde do Brasil, grant number 25000.056766/2015-64. E.I.P., M.E.M. and R.M.R. were also supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rahman N. Realizing the promise of cancer predisposition genes. Nature. 2014;505:302–308. doi: 10.1038/nature12981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang K., Mashl R.J., Wu Y., Ritter D.I., Wang J., Oh C., Paczkowska M., Reynolds S., Wyczalkowski M.A., Oak N., et al. Pathogenic germline variants in 10,389 adult cancers. Cell. 2018;173:355–370.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch H.T., Snyder C.L., Shaw T.G., Heinen C.D., Hitchins M.P. Milestones of lynch syndrome: 1895–2015. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:181–194. doi: 10.1038/nrc3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carethers J.M. Differentiating lynch-like from lynch syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:602–604. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porkka N., Lahtinen L., Ahtiainen M., Böhm J.P., Kuopio T., Eldfors S., Mecklin J.P., Seppälä T.T., Peltomäki P. Epidemiological, clinical and molecular characterization of lynch-like syndrome: A population-based study. Int. J. Cancer. 2019;145:87–98. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picó M.D., Castillejo A., Murcia Ó., Giner-Calabuig M., Alustiza M., Sánchez A., Moreira L., Pellise M., Castells A., Carrillo-Palau M., et al. Clinical and pathological characterization of lynch-like syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;18:368–374.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Win A.K., Buchanan D.D., Rosty C., MacInnis R.J., Dowty J.G., Dite G.S., Giles G.G., Southey M.C., Young J.P., Clendenning M., et al. Role of tumour molecular and pathology features to estimate colorectal cancer risk for first-degree relatives. Gut. 2015;64:101–110. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xicola R.M., Clark J.R., Carroll T., Alvikas J., Marwaha P., Regan M.R., Lopez-Giraldez F., Choi J., Emmadi R., Alagiozian-Angelova V., et al. Implication of DNA repair genes in lynch-like syndrome. Fam. Cancer. 2019;18:331–342. doi: 10.1007/s10689-019-00128-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Paula A.E., de Galvão H.C.R., Bonatelli M., Sabato C., Fernandes G.C., Berardinelli G.N., Andrade C.E.M., Neto M.C., Romagnolo L.G.C., Campacci N., et al. Clinicopathological and molecular characterization of brazilian families at risk for lynch syndrome. Cancer Genet. 2021;254–255:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castillejo A., Vargas G., Castillejo M.I., Navarro M., Barberá V.M., González S., Hernández-Illán E., Brunet J., Ramón Y., Cajal T., et al. Prevalence of germline MUTYH mutations among lynch-like syndrome patients. Eur. J. Cancer. 2014;50:2241–2250. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morak M., Heidenreich B., Keller G., Hampel H., Laner A., De La Chapelle A., Holinski-Feder E. Biallelic MUTYH mutations can mimic lynch syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;22:1334–1337. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansen A.M., Van Wezel T., Van Den Akker B.E., Ventayol Garcia M., Ruano D., Tops C.M., Wagner A., Letteboer T.G., Gómez-García E.B., Devilee P., et al. Combined mismatch repair and POLE/POLD1 defects explain unresolved suspected lynch syndrome cancers. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;24:1089–1092. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xavier A., Olsen M.F., Lavik L.A., Johansen J., Singh A.K., Sjursen W., Scott R.J., Talseth-Palmer B.A. Comprehensive mismatch repair gene panel identifies variants in patients with lynch-like syndrome. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2019;7:e850. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golubicki M., Bonjoch L., Acuña-Ochoa J.G., Díaz-Gay M., Muñoz J., Cuatrecasas M., Ocaña T., Iseas S., Mendez G., Cisterna D., et al. Germline biallelic Mcm8 variants are associated with early-onset lynch-like syndrome. JCI Insight. 2020;5:1–15. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.140698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmero E.I., Galvão H.C.R., Fernandes G.C., De Paula A.E., Oliveira J.C., Souza C.P., Andrade C.E., Romagnolo L.G.C., Volc S., Neto M.C., et al. Oncogenetics service and the brazilian public health system: The experience of a reference cancer hospital. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2016;39:168–177. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-gmb-2014-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Garcia F.A.O., de Andrade E.S., de Campos Reis Galvão H., da Silva Sábato C., Campacci N., de Paula A.E., Evangelista A.F., Santana I.V.V., Melendez M.E., Reis R.M., et al. New insights on familial colorectal cancer type X syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06782-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingett S.W., Andrews S. FastQ Screen: A Tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Research. 2018;7:1338. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.15931.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 2011;17:10. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picard Toolkit, 2019. Broad Institute, Repository. [(accessed on 12 April 2022)]. Available online: http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/

- 21.Depristo M.A., Banks E., Poplin R., Garimella K.V., Maguire J.R., Hartl C., Philippakis A.A., Del Angel G., Rivas M.A., Hanna M., et al. A Framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:491–501. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poplin R., Ruano-Rubio V., DePristo M.A., Fennell T.J., Carneiro M.O., Van der Auwera G.A., Kling D.E., Gauthier L.D., Levy-Moonshine A., Roazen D., et al. Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples. bioRxiv. 2017:1–22. doi: 10.1101/201178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tate J.G., Bamford S., Jubb H.C., Sondka Z., Beare D.M., Bindal N., Boutselakis H., Cole C.G., Creatore C., Dawson E., et al. COSMIC: The catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941–D947. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bateman A. UniProt: A worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D506–D515. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pletscher-Frankild S., Pallejà A., Tsafou K., Binder J.X., Jensen L.J. DISEASES: Text mining and data integration of disease-gene associations. Methods. 2015;74:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stelzer G., Rosen N., Plaschkes I., Zimmerman S., Twik M., Fishilevich S., Stein T.I., Nudel R., Lieder I., Mazor Y., et al. The genecards suite: From gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 2016;54:1.30.1–1.30.33. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spatz M.A. Genetics home reference. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2004;92:282–283. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das R., Ghosh S.K. Genetic variants of the DNA repair genes from exome aggregation consortium (EXAC) database: Significance in cancer. DNA Repair. 2017;52:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–423. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Wenger A.M., Zehir A., Mesirov J.P. Variant review with the integrative genomics viewer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e31–e34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y., Muzny D.M., Xia F., Niu Z., Person R., Ding Y., Ward P., Braxton A., Wang M., Buhay C., et al. Molecular findings among patients referred for clinical whole-exome sequencing. JAMA. 2014;312:1870. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertier G., Hétu M., Joly Y. Unsolved challenges of clinical whole-exome sequencing: A systematic literature review of end-users’ views Donna Dickenson, Sandra Soo-Jin Lee, and Michael Morrison. BMC Med. Genom. 2016;9:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12920-016-0213-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esteban-Jurado C., Garre P., Vila M., Lozano J.J., Pristoupilova A., Beltrán S., Abulí A., Muñoz J., Balaguer F., Ocaña T., et al. New genes emerging for colorectal cancer predisposition. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1961–1971. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i8.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trujillano D., Bertoli-Avella A.M., Kumar Kandaswamy K., Weiss M.E., Köster J., Marais A., Paknia O., Schröder R., Garcia-Aznar J.M., Werber M., et al. Clinical exome sequencing: Results from 2819 samples reflecting 1000 families. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25:176–182. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elsayed F.A., Kets C.M., Ruano D., van den Akker B., Mensenkamp A.R., Schrumpf M., Nielsen M., Wijnen J.T., Tops C.M., Ligtenberg M.J., et al. Germline variants in POLE are associated with early onset mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;23:1080–1084. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearlman R., Frankel W.L., Swanson B., Zhao W., Yilmaz A., Miller K., Bacher J., Bigley C., Nelsen L., Goodfellow P.J., et al. Prevalence and spectrum of germline cancer susceptibility gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:464. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma H., Brosens L.A.A., Offerhaus G.J.A., Giardiello F.M., de Leng W.W.J., Montgomery E.A. Pathology and genetics of hereditary colorectal cancer. Pathology. 2018;50:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ali M., Kim H., Cleary S., Cupples C., Gallinger S., Bristow R. Characterization of Mutant MUTYH proteins associated with familial colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:499–507. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones N., Vogt S., Nielsen M., Christian D., Wark P.A., Eccles D., Edwards E., Evans D.G., Maher E.R., Vasen H.F., et al. Increased colorectal cancer incidence in obligate carriers of heterozygous mutations in MUTYH. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:489–494.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Win A.K., Cleary S.P., Dowty J.G., Baron J.A., Young J.P., Buchanan D.D., Southey M.C., Burnett T., Parfrey P.S., Green R.C., et al. Cancer risks for monoallelic MUTYH mutation carriers with a family history of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2011;129:2256–2262. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moldovan G.-L., Madhavan M.V., Mirchandani K.D., McCaffrey R.M., Vinciguerra P., D’Andrea A.D. DNA polymerase poln participates in cross-link repair and homologous recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30:1088–1096. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01124-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant R.C., Denroche R.E., Borgida A., Virtanen C., Cook N., Smith A.L., Connor A.A., Wilson J.M., Peterson G., Roberts N.J., et al. Exome-wide association study of pancreatic cancer risk. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:719–722.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu J., Wei Y., Pan J., Jin S., Gu W., Gan H., Zhu Y., Ye D.W. Prevalence of comprehensive DNA damage repair gene germline mutations in Chinese prostate cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer. 2021;148:673–681. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dicks E., Song H., Ramus S.J., Van Oudenhove E., Tyrer J.P., Intermaggio M.P., Kar S., Harrington P., Bowtell D.D., Cicek M.S., et al. Germline whole exome sequencing and large-scale replication identifies FANCM as a likely high grade serous ovarian cancer susceptibility gene. Oncotarget. 2017;8:50930–50940. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarafa G., Villanueva A., Farré L., Rodríguez J., Musulén E., Reyes G., Seminago R., Olmedo E., Paules A.B., Peinado M.A., et al. DCC and SMAD4 Alterations in human colorectal and pancreatic tumor dissemination. Oncogene. 2000;19:546–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polvi A., Linnankivi T., Kivelä T., Herva R., Keating J.P., Mäkitie O., Pareyson D., Vainionpää L., Lahtinen J., Hovatta I., et al. Mutations in CTC1, encoding the CTS telomere maintenance complex component 1, cause cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson B.H., Kasher P.R., Mayer J., Szynkiewicz M., Jenkinson E.M., Bhaskar S.S., Urquhart J.E., Daly S.B., Dickerson J.E., O’Sullivan J., et al. Mutations in CTC1, encoding conserved telomere maintenance component 1, cause coats plus. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:338–342. doi: 10.1038/ng.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen W., Kerr C.M., Przychozen B., Mahfouz R.Z., LaFramboise T., Nagata Y., Hanna R., Radivoyevitch T., Nazha A., Sekeres M.A., et al. Impact of germline CTC1 alterations on telomere length in acquired bone marrow failure. Br. J. Haematol. 2019;185:935–939. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim B., Yun W., Lee S.T., Choi J.R., Yoo K.H., Koo H.H., Jung C.W., Kim S.H. Prevalence and clinical implications of germline predisposition gene mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Sci. Rep. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71386-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liao H.F., Lee H.H., Chang Y.S., Lin C.L., Liu T.Y., Chen Y.C., Yen J.C., Lee Y.T., Lin C.Y., Wu S.H., et al. Down-regulated and commonly mutated ALPK1 in lung and colorectal cancers. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep27350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jandrig B., Seitz S., Hinzmann B., Arnold W., Micheel B., Koelble K., Siebert R., Schwartz A., Ruecker K., Schlag P.M., et al. ST18 is a breast cancer tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 8q11.2. Oncogene. 2004;23:9295–9302. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Capaccio D., Ciccodicola A., Sabatino L., Casamassimi A., Pancione M., Fucci A., Febbraro A., Merlino A., Graziano G., Colantuoni V. A novel germline mutation in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ gene associated with large intestine polyp formation and dyslipidemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2010;1802:572–581. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith W.M., Zhou X.P., Kurose K., Gao X., Latif F., Kroll T., Sugano K., Cannistra S.A., Clinton S.K., Maher E.R., et al. Opposite association of two PPARG variants with cancer: Overrepresentation of H449H in endometrial carcinoma cases and underrepresentation of P12A in renal cell carcinoma cases. Hum. Genet. 2001;109:146–151. doi: 10.1007/s004390100563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitui M., Campbell C., Coutinho G., Sun X., Lai C.H., Thorstenson Y., Castellvi-Bel S., Fernandez L., Monros E., Carvalho B.T.C., et al. Independent mutational events are rare in the ATM Gene: Haplotype prescreening enhances mutation detection rate. Hum. Mutat. 2003;22:43–50. doi: 10.1002/humu.10232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tung N., Lin N.U., Kidd J., Allen B.A., Singh N., Wenstrup R.J., Hartman A.R., Winer E.P., Garber J.E. Frequency of germline mutations in 25 cancer susceptibility genes in a sequential series of patients with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:1460–1468. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young E.L., Thompson B.A., Neklason D.W., Firpo M.A., Werner T., Bell R., Berger J., Fraser A., Gammon A., Koptiuch C., et al. Pancreatic cancer as a sentinel for hereditary cancer predisposition. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4573-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Variants classified will be deposited in the ClinVar database. Data that support the findings are not readily available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Requests for data access should be directed to the corresponding author, Edenir Inez Palmero.