Abstract

Marinomonas mediterranea is a melanogenic marine bacterium expressing a multifunctional polyphenol oxidase (PPO) able to oxidize substrates characteristic for laccases and tyrosinases, as well as produce a classical tyrosinase. A new and quick method has been developed for screening laccase activity in culture plates to detect mutants differentially affected in this PPO activity. Transposon mutagenesis has been applied for the first time to M. mediterranea by using different minitransposons loaded in R6K-based suicide delivery vectors mobilizable by conjugation. Higher frequencies of insertions were obtained by using mini-Tn10 derivatives encoding kanamycin or gentamycin resistance. After applying this protocol, a multifunctional PPO-negative mutant was obtained. By using the antibiotic resistance cassette as a marker, flanking regions were cloned. Then the wild-type gene was amplified by PCR and was cloned and sequenced. This is the first report on cloning and sequencing of a gene encoding a prokaryotic enzyme with laccase activity. The deduced amino acid sequence shows the characteristic copper-binding sites of other blue copper proteins, including fungal laccases. In addition, it shows some extra copper-binding sites that might be related to its multipotent enzymatic capability.

Melanins are dark-colored polyphenolic pigments synthesized by different organisms through the entire phylogenetic scale, from bacteria to mammals. In higher organisms and some bacteria, such as Streptomyces and Rhizobium, melanin is made by using l-tyrosine as a precursor and tyrosinase as the key enzyme (EC 1.14.18.1). This enzyme catalyzes two reactions (31): ortho hydroxylation of l-tyrosine (cresolase activity) into l-dopa and its subsequent oxidation to yield l-dopaquinone (catecholase activity). After formation of this o-quinone, the pathway can proceed spontaneously since that quinonic compound is very reactive, and it undergoes a series of reactions involving oxidation, isomerization, and polymerization that lead to the final melanin pigment.

Tyrosinases are polyphenol oxidases (PPOs) that belong to the group of nonblue copper proteins. The other important group of PPOs are the blue-copper proteins named laccases (EC 1.10.3.2) since their first description was in the lacquer tree (42). Laccases are multicopper proteins characterized by the presence in the molecule of three different types of copper (28), whereas tyrosinases only have a pair of type III coppers. Experimentally, tyrosinases and laccases have been classically differentiated on the basis of substrate specificity and sensitivity to inhibitors, although they are able to oxidize an overlapping range of diphenolic compounds. The most important difference is that only tyrosinases show cresolase activity and only laccases are able to oxidize methoxy-activated phenols such as syringaldazine (40).

In fact, laccases have been found abundantly distributed in plants and numerous fungi, where its involvement in melanin formation and a variety of different, and sometimes contradictory, physiological functions has been frequently proposed (40). In bacteria, laccase activity has been rarely described. It was described for the first time in Azospirillum lipoferum (19) and more recently in two marine bacteria, Marinomonas mediterranea and strain 2-40 (37). Strikingly, laccase activity in these marine strains is due to a unique multifunctional PPO that shows not only laccase but also tyrosinase activity.

M. mediterranea is a melanogenic bacterium recently isolated from the Mediterranean Sea (36, 37). It is the first prokaryotic cell found to show tyrosinase and laccase activities, since it contains two different PPOs. One of them appears to be a classical sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-activated tyrosinase, similar to some eukaryotic tyrosinases (29, 41). The other PPO is a multipotent enzyme able to oxidize a wide range of substrates characteristic for both tyrosinases and laccases (34). This enzyme has been partially purified and characterized as a blue multicopper membrane-bound protein (18).

It has also been found that tyrosinase and laccase are simultaneously expressed in some fungi (23), and different isozymes of these PPOs are present in numerous species (16, 25). It is assumed that tyrosinase is involved in melanin synthesis and laccase is involved in other cellular processes such as formation of fruiting bodies, sexual differentiation, and lignolysis. However, the functions of each enzyme have never been well delimited.

The unique characteristics of M. mediterranea PPOs made us think that it would be an interesting model with which to gain knowledge on the physiological roles of tyrosinases and laccases. Due to the overlapping substrate specificities and a series of common features (enzymatic copper proteins, etc.), the classical methods for protein purification are not enough to unambiguously distinguish the function and properties of each enzyme; therefore, molecular techniques are necessary. Unlike chemical mutagenesis, transposon-generated mutations determine gene disruption, being very powerful tools for the genetic analysis of bacteria (7, 13). So far, those molecular techniques have been rarely applied to marine bacteria. To our knowledge, transposon mutagenesis has been applied to members of the genus Vibrio (6) and to a Pseudomonas strain (1, 39), but there is no report on its application to the genus Alteromonas or Marinomonas. In this paper, we describe the development of transposon mutagenesis for M. mediterranea. This technique has allowed us to obtain a mutant strain affected in the multipotent PPO and to clone the gene encoding this enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Inorganic salts to prepare buffers and culture media were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Peptones and yeast extract were from Oxoid Ltd. (Basingstoke, England). All substrates for the enzymatic assays and the antibiotics were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.), except 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (DMP), which was from Fluka Chemie (Bucks, Switzerland). Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (33). When required, this medium was supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain | Description and/or relevant genotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| M. mediterranea | ||

| MMB-1 | Wild type, Rifs Gms | 36 |

| MMB-1R | MMB-1, spontaneously Rifr | This work |

| ng56 | MMB-1, ng mutant, amelanotic | 36 |

| ngd67 | MMB-1, ng mutant, DMPO (−) | This work |

| Tn101 | MMB-1R, ppoA::Tn10(Gm) | This work |

| E. coli S17-1 (λpir) | Tpr Smr, recA thi hsdRM+, λpir phage lysogen RP4::Mu::Km Tn7 | 13 |

| E. coli DH5α | Commercially available | |

| E. coli ED 8654 | Commercially available | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUX1Lac | pUEX1 + 2.8-kb laccase gene from basidiomycete PM1 | 9 |

| pMELD | pGEM-T + 1.5-kb tyrosinase gene from R. meliloti GR4 | 27 |

| pABOR70 | Apr, Tn10-based mel delv. vt. | 21 |

| pCOS5 | Apr Cmr, cosmid vector | 10 |

| pSUP102-Gm Tn5-B21 | ori p15A, mob RP4, Cmr Gmr; Tn5:LacZ Tcr, delv. vt. | 35 |

| pBSL299 | ori R6K, mob RP4, Apr; mini-Tn5 Smr, delv. vt. | 4 |

| pUT Tc | ori R6K, mob RP4, Apr; mini-Tn5 Tcr, delv. vt. | 12 |

| pUT Km | ori R6K, mob RP4, Apr; mini-Tn5 Kmr, delv. vt. | 12 |

| pLOFKm | ori R6K, mob RP4, Apr; mini-Tn10 Kmr, delv. vt. | 21 |

| pLBT | ori R6K, mob RP4, Apr; mini-Tn10:lac:kan, delv. vt. | 1 |

| pBSL181 | ori R6K, mob RP4, Apr; mini-Tn10 Cmr, delv. vt. | 3 |

| pBSL182 | ori R6K, mob RP4, Apr; mini-Tn10 Gmr, delv. vt. | 3 |

| pKT230 | Double replicon, ori p15A, IncQ/P4 incompatibility group, mob RP4, Smr Kmr | 5 |

| pUC19 | Commercially available | |

| pLB1 | Apr Gmr; pUC19 + 12.7-kb SphI fragment of chromosomal DNA from strain Tn101 | This work |

| pPPO | Apr, pUC19 + 2.2-kb HindIII-EcoRI PCR-generated fragment containing ppoA | This work |

| pBluescriptKSII | Commercially available | |

| pKα | Apr, pBKSII + 1.5-kb SacI-XhoI fragment of chromosomal DNA from strain Tn101 | This work |

| pKβ | Apr, pBKSII + 3.7-kb SacI-XhoI fragment of chromosomal DNA from strain Tn101 | This work |

| pKK | Apr, pBKSII + 2.4-kb SacI-KpnI fragment subcloned from pKβ | This work |

delv. vt., delivery vector; ng, nitrosoguanidine.

M. mediterranea was usually grown in marine broth, Agar 2216 (Difco), or several marine media (complex MMC, DIC, and minimal MMM). MMC has been previously described (18). DIC is a modification of MMC in which no Mg2+ was added to allow detection of tetracycline resistance. This medium contained per liter: 30 g of NaCl, 4 g of Na2SO4, 0.7 g of KCl, 1.25 g of CaCl2, 75 mg of K2HPO4, 100 mg of iron citrate, 5 g of peptone, and 1 g of yeast extract. MMM is a chemically defined medium containing, per liter, 20 g of NaCl, 7 g of MgSO4 7H2O, 5.3 g of MgCl2 5H2O, 0.7 g of KCl, 1.25 g of CaCl2, 25 mg of FeSO4 7H2O, 5 mg of CuSO4 5H2O, 75 mg of K2HPO4, 2 g of sodium glutamate, and 6.1 g of Tris base. The media were adjusted to pH 7.4.

Conjugation and transposon mutagenesis.

Plasmids containing different transposons were mobilized from donor E. coli S17-1 (λpir) into M. mediterranea by conjugation. Usually, the spontaneous rifampicin-resistant (Rifr) M. mediterranea MMB-1R was used, so that antibiotic was added to MMC to counterselect E. coli. It was also possible to counterselect E. coli by growing the cells in MMM. Donor and recipient strains were grown overnight in LB and MMC media, respectively, with appropriate antibiotics for plasmid and transposon resistance markers. Then, both strains were reinoculated into fresh media without antibiotics and were allowed to reach the exponential phase of growth. Conjugation was performed on the surface of an agar plate. Several media were assayed: LB with 15 g of NaCl per liter, marine agar 2216, and LB2216, obtained by mixing equal amounts of the previous two media. A 40-μl sample of the exponentially growing recipient cells was spotted on the surface of the plate and allowed to dry before 40 μl of the donor E. coli was added onto the previous spot. Controls with only M. mediterranea or E. coli were also carried out. The plates were incubated overnight and then cells were collected by scraping and were suspended in 1 ml of MMC. Appropriate dilutions were plated on selective media. A second antibiotic to which the transposon or plasmid encoded resistance was also included. A series of preliminary experiments were performed to establish optimal antibiotic concentrations for M. mediterranea.

Total numbers of recipient cells were calculated by plating the conjugation suspension in MMC with rifampicin (50 μg/ml). Transposition frequencies were calculated as the ratio of recipient cells expressing transposon-encoded antibiotic resistance versus the total number of cells. In order to check the stability of the delivery vector in the recipient cell, cellular suspensions were also plated in media containing the plasmid marker.

Southern blot analysis and probe labeling.

Chromosomal DNA was extracted from several independent transconjugants: Rifr, ampicillin-sensitive (Amps), gentamycin-resistant (Gmr), or kanamycin-resistant (Kmr) M. mediterranea obtained after the E. coli S17-1 (λpir) (pBSL182) or (pLBT) × M. mediterranea MMB-1R matings. Southern blot analysis was carried out after digesting these samples with different restriction enzymes. A 0.9-kb SacI fragment of pBSL182 or a NotI fragment of pLBT encompassing the genes coding for antibiotic resistances was used as a digoxigenin-labeled probe.

Probes encoding tyrosinases from Rhizobium meliloti (27) or Streptomyces (21) or PM1 laccase (9) were labeled with [α-32P]ATP by using random primers (Boehringer radiolabeling kit) to explore possible homologue genes. ppoA was also labeled in the same way for use as a probe in Northern blotting. RNA was isolated from M. mediterranea cultures in exponential and early stationary phase by centrifugation in CsCl.

Screening for mutants affected in PPO activity.

M. mediterranea mutants affected in melanization were detected by visually inspecting the pigmentation of the surviving colonies in complex medium (MMC). Mutants in laccase activity were detected in 0.5% agarose plates containing 2 mM DMP in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 5. Surviving microorganisms were allowed to grow for 3 or 4 days and were then replicated by using a toothpick in DMP and MMC plates. Laccase activity was detected by the quick appearance of a bright orange color in the DMP plate.

Cloning of the transposon-interrupted and complete ppoA genes from M. mediterranea.

Isolated genomic DNA of M. mediterranea Tn101 was digested with SphI and ligated to pUC19 digested with the same enzyme. The ligation mixture was transformed in E. coli DH5α, and transformants were selected for ampicillin and gentamycin resistance. The plasmid obtained (LB1) was subcloned in pBluescript KS II by using the SacI restriction sites that the transposon has close to both IS10 sequence edges and XhoI or KpnI restriction sites in the M. mediterranea chromosomic DNA. The DNA adjacent to the insertion point was sequenced by using the forward and reverse M13 universal primers.

The complete ppoA gene was amplified from the chromosome of wild-type M. mediterranea by PCR by using the proofreading Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and the primers MFEF (forward), TTGAAGCTTCCATAGACAGCAATCTAAC, and MFER (reverse), TTTGAATTCATGCACCAGTCTGCTT, designed from the LB1 plasmid sequence. These oligonucleotides respectively incorporated cloning HindIII and EcoRI restriction sites. PCR consisted of 25 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 61°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 6 min 15 s. The mixture contained 5% dimethylsulfoxide, 1 μg of each primer, and 100 ng of template DNA. After digestion of the amplified product with the mentioned enzymes, it was cloned in pUC19, yielding a plasmid with an insert of approximately 2.2 kb.

Enzymatic determinations in cell extracts and gel electrophoresis.

Total cell extracts, membrane, and soluble fractions were prepared as previously described (18). Tyrosine hydroxylase and dopa oxidase activities were determined by monitoring the respective oxidations of 2 mM l-tyrosine and l-dopa at 475 nm in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 5.0. For tyrosine hydroxylase activity, 25 μM l-dopa was added to the assay mixture to eliminate the lag period (37). When required, the activities were also assayed in the presence of 0.02% SDS. Dimethoxyphenol oxidase and syringaldazine oxidase activities were respectively determined by monitoring the oxidation of 2 mM DMP at 468 nm in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 5.0, or the oxidation of 50 μM syringaldazine at 525 nm, pH 6.5 (36). Reference cuvettes always had the same composition except for the enzymatic extract. In all cases, 1 U was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the appearance of 1 μmol of product per min at 37°C. Specific activities were normalized by milligram of protein, measured by using the bicinchoninic acid kit (Pierce Europe). Polyacrylamide electrophoresis under nondissociating conditions and subsequent specific PPO gel staining using l-dopa in the presence or absence of SDS were performed as previously described (36).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the ppoA gene of M. mediterranea reported in this paper has been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession number AF184209.

RESULTS

Laccase activity detection and transposon mutagenesis in M. mediterranea.

In a previous report, we communicated that amelanotic M. mediterranea mutants selected after nitrosoguanidine treatment were specifically affected in the SDS-activated tyrosinase activities (36). We were also interested in obtaining complementary mutants affected in the multipotent laccase-like PPO, the second PPO that this microorganism seemed to contain. Different methods were assayed in order to simplify the detection of this enzymatic activity. The addition to the culture plates of laccase substrates, such as guaiacol, did not allow the detection of this activity, mainly because the appearance of dark bacterial melanin hindered the observation of the expected yellowish-colored product resulting from laccase action on that substrate. However, laccase activity could be easily detected by taking part of a colony with a toothpick and picking it in a 0.5% agarose plate containing 2 mM DMP. Under these conditions, the wild-type M. mediterranea, as well as the amelanotic mutant strain ng56 (36), yielded a bright orange color. The applicability of this method to detect null-laccase mutants was checked by submitting M. mediterranea to nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis. It was observed that it could be possible to isolate mutants, such as ngd67, with a phenotype complementary to strain ng56. That is, they produced melanins but did not show laccase activity.

We approached the problem of cloning the gene by transposon mutagenesis. As this technique has not been previously reported for study of the genus Marinomonas, different transposons and delivery vectors were assayed. The conditions of conjugation between E. coli S-17 and M. mediterranea were optimized by using plasmids pKT230 and pSUP102Gm. These plasmids contain the mob region from plasmid RP4 and the p15 origin of replication. They could be mobilized at high frequencies and were able to replicate in M. mediterranea (Table 2). At 25°C, the mixed LB2216 medium yielded higher conjugation frequencies than cultures at 37°C or other media, so these conditions were selected for conjugation experiments.

TABLE 2.

Exconjugant frequencies obtained by conjugation between M. mediterranea and E. coli S17-1 (λpir)

| Vector | Transposon | Selection medium and marker (μg/ml)a | Resistance frequency | Spontaneous resistance | Plasmid replicationb | Transposition event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pKT230 | None | MMC Rif Km (50) | 1 × 10−2 | <10−8 | + | |

| pKT230 | None | MMM Km (50) | 2 × 10−2 | <10−8 | + | |

| pSUP102-Gm | Tn5-B21 | DIC Rif Tc (10) | 5.8 × 10−4 | <10−8 | +(Cmr Gmr) | − |

| pUT Tc | mini-Tn5 Tc | DIC Rif Tc (10) | <10−8 | <10−8 | − | − |

| pBSL299 | mini-Tn5 | 2216 Rif Sm (10) | 8 × 10−6 | 5.6 × 10−6 | − | − |

| pUT Km | mini-Tn5 | MMC Rif Km (50) | 3.1 × 10−6 | <10−8 | − | + |

| pBSL181 | mini-Tn10 | MMC Rif Cm (10) | <10−8 | <10−8 | − | − |

| pBSL182 | mini-Tn10 | MMC Rif Gm (10) | 9.5 × 10−5 | 3 × 10−7c | − | + |

| pLOF Km | mini-Tn10 | MMC Rif Km (50) | 6.6 × 10−4 | <10−8 | − | + |

| pLBT | mini-Tn10:lac:km | MMC Rif Km (50) | 1.1 × 10−4 | <10−8 | − | + |

Rif, rifampicin; Km, kanamycin; Tc, tetracycline; Cm, chloramphenicol; Gm, gentamycin; Sm, streptomycin.

Estimated by determining growth in the presence of the antibiotic whose resistance is plasmid encoded.

Spontaneous Gmr mutants resulted in very small colonies that were easily differentiated from true transpositions.

Plasmids containing the ori R6K behaved as true suicidal vectors in M. mediterranea. Thus, several plasmid derivatives containing mini-Tn5 (4, 13) and mini-Tn10 (3, 21) were tested (Table 2). Mini-Tn10 derivatives yielded higher exconjugant frequencies than mini-Tn5, although the antibiotic marker also affected that parameter. The best transposition results were obtained with kanamycin and gentamycin as resistance markers.

Chromosomal DNA was extracted from several independent transconjugants of M. mediterranea obtained after the E. coli S17-1 (λpir) (pBSL182) or (pLBT) × M. mediterranea MMB-1R matings. Southern blot analyses were carried out by using the genes coding for antibiotic resistance as probes. A single band of different sizes was observed in each one, indicating that a single, random insertion event took place (data not shown).

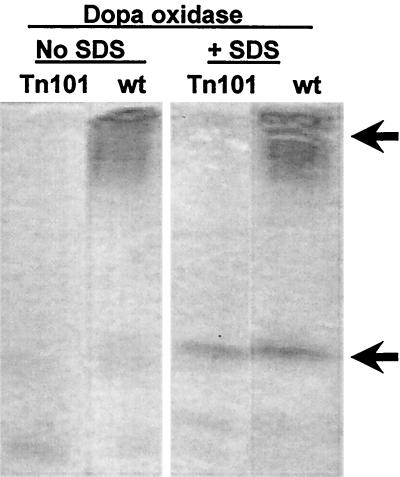

Several thousand exconjugants obtained by using plasmid pBSL182, pLOFKm, or pLBT were inspected for the formation of dark-pigmented melanized colonies and for their capacity to oxidize DMP. One mini-Tn10 mutant affected in the oxidation of DMP was detected, although we were unable to detect any amelanotic mutants. This mutant was obtained by using plasmid pBSL182, and hence, it was Gmr. It was denominated M. mediterranea Tn101, and it was phenotypically very similar to nitrosoguanidine mutant ngd67. Consistent with the qualitative tests used for mutant detection, the enzymatic oxidase assays indicated that both strains retained soluble SDS-activated tyrosinase activities, but they were affected in membrane-bound multipotent PPO activity (Table 3). In addition, when cellular extracts of wild-type M. mediterranea and mutant strain Tn101 were subject to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under nondissociating conditions (36), it was observed that the mutant strain retained the SDS-activated tyrosinase while the broad band corresponding to the membrane-bound PPO was lost (Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

Specific activities (milliunits per milligram) in the soluble and membrane fractions of cell extracts from wild-type and mutant M. mediterranea strains

| Activitya | Wild type | Tn101 | ngd67 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble | |||

| TH | 20.1 | 14.1 | 17.6 |

| THSDS | 243.8 | 683.7 | 420.0 |

| DO | 106.0 | 74.2 | 80.2 |

| DOSDS | 916.2 | 954.0 | 916.0 |

| DMPO | 226.5 | NDb | ND |

| SO | 51.3 | ND | ND |

| Membrane bound | |||

| TH | 88.5 | ND | ND |

| DO | 839.0 | ND | ND |

| DMPO | 3,572.3 | ND | ND |

| SO | 895.5 | ND | ND |

TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; DO, dopa oxidase; DMPO, dimethoxyphenol oxidase; SO, syringaldazine oxidase; THSDS, TH in the presence of 0.02% SDS; DOSDS, DO in the presence of 0.02% SDS.

ND, not detectable.

FIG. 1.

Electrophoretic analysis of the PPO activity in wild-type (wt) M. mediterranea and mutant strain Tn101. Polyacrylamide gels (10%) were run under nondissociating conditions and were stained for dopa oxidase activity in the absence and presence of 0.02% SDS. Upper arrow points to the multipotent PPO that can be stained with either laccase or tyrosinase substrates. Lower arrow points to the SDS-activated tyrosinase.

ppoA sequencing and analysis.

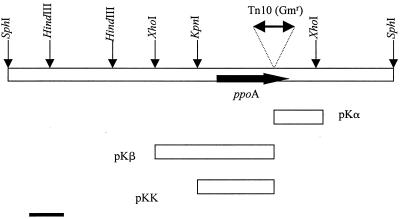

The chromosomal region flanking the mini-Tn10 insertion in M. mediterranea Tn101 was cloned by a marker rescue experiment. Chromosomal DNA from this strain was digested with the restriction enzyme SphI and was ligated to pUC19. The transformants in E. coli DH5α were selected for gentamycin and ampicillin resistance. A plasmid (pLB1) was obtained with an insert containing the mini-Tn10 transposon and two flanking regions of M. mediterranea chromosomal DNA of approximately 8.1 and 3.8 kb (Fig. 2). The two SacI restriction sites close to both IS10 sequences of the transposon were used for subcloning the flanking regions to the insertion point. SacI/XhoI digestions of pLB1 were ligated to the corresponding site of plasmid pBluescript KS II obtaining plasmids pKα and pKβ comprising, respectively, the sequences downstream and upstream of the transposon insertion site. Finally, a SacI/KpnI fragment of plasmid pKβ was subcloned into pUC19, generating the plasmid pKK (Fig. 2). The sequencing of the plasmids pKα and pKK indicated that the transposon was inserted in an open reading frame 1 (ORF1), designated ppoA for PPO, of 2,091 bp (GenBank accession no. AF184209). The accuracy of the sequence was checked by PCR amplification from wild-type M. mediterranea and sequencing this ppoA. The analysis of this sequence revealed that the transposon had inserted in the chromosome, generating a 9-bp direct duplication that is a characteristic feature of Tn10 (7).

FIG. 2.

Genetic map of the chromosomal region around ppoA cloned in plasmid LB1, by marker rescue. The site of Tn10 insertion is marked by a triangle. Relevant restriction sites are marked. The fragments subcloned in different plasmids are indicated at the bottom. Bar = 1 kb.

ORF1 starts with two codons, TTG and ATG, that might encode the initial methionine. However, no putative ribosome binding site could be detected upstream of them. Thus, the methionine situated at position 22 in this ORF1 seems to be the most likely candidate for the transductional start of ppoA, as it is preceded by a region resembling the promoter consensus, as well as by a putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence. In consequence, a protein of 675 amino acids showing a signal peptide seems to be codified by the ppoA gene. Another feature of this gene is that 21 nucleotides downstream of the TAA stop codon, a palindromic sequence was found (AAAAGCGAGCCAAAGGCTCGCTTTT) that is a putative intrinsic transcription terminal signal.

ppoA is preceded by a small ORF2 of 309 bp, not showing homology to any other gene. The sequencing of the approximately 400 bp upstream of the ORF2 to complete the insert in pKK revealed what seemed to be the 3′ end of another gene.

Preliminary experiments studying regulation reveal that the ppoA gene seems to be transcriptionally regulated and that the proposed promoter is controlling its expression. Northern analysis with 32P-labeled ppoA probe reveals a significant increase in the mRNA content of M. mediterranea cultures reaching the early stationary phase. However, the increase in mRNA is not comparable to the large increase in the enzymatic activity observed at that stage (18).

The sequence deduced for PpoA shows all four characteristic copper-binding sites of blue copper proteins. Table 4 shows an alignment among the different prokaryotic blue copper proteins and the deduced sequence from the cloned ORF1, illustrating that the four copper-binding sites are very well conserved. Moreover, ORF1 has other additional histidine clusters (29HQTDHASH and 167HHNH) that might also be involved in additional copper binding and might be related to the multifunctional activity of this enzyme, sharing laccase and tyrosinase capabilities (34).

TABLE 4.

Alignment of the four characteristic copper-binding sites (A, B, C, and D) in some prokaryotic blue multicopper proteins and a fungal laccase included for comparison

| Proteina | Copper-binding site

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| M. mediterranea, PpoA (AF184209) | HTH | HAH | HPYHIH | HCHILDH |

| P. syringae, Cu resistance (P12374) | HWH | HSH | HPIHLH | HCHLLYH |

| X. campestris, Cu resistance (L19222) | HWH | HSH | HPIHLH | HCHLLYH |

| E. coli, hypothetical protein (AAC73234) | HWH | HPH | HPFHIH | HCHLLEH |

| Streptomyces antibioticus, phenoxazinone synthase (Q53692) | HLH | HDH | HPMHIH | HCHLLEH |

| A. aoelicus, hypothetical protein (AAC07157.1) | HWH | HPH | HPMHIH | HCHILEH |

| Bacillus subtilis, CotA (P07788) | HLH | HDH | HILIHLH | HCHILEH |

| Basidiomycete PM1 laccase (Z12156) | HWH | HSH | HPFHLH | HCHIDFH |

Protein accession numbers appear in parentheses.

Regarding the ppoA gene in mutant strains, the site of the Tn10 insertion in the mutant Tn101 was located relatively close to the 3′ extreme of the gene, truncating the ORF1 at 529M. Furthermore, the ppoA gene from mutant strain ngd67 was also amplified and sequenced, revealing a nonsense mutation in which the codon 328 (TGG) coding for W changed to stop codon TGA. In both cases, copper-binding motifs C and D are suppressed, supporting the complete lost of enzymatic activity. On the other hand, no mutation was detected in the ppoA gene of the amelanotic mutant ng56.

DISCUSSION

Based on kinetic data and cellular localization studies, we had proposed that M. mediterranea is a melanogenic bacterium containing two different PPOs (36): an unusual multipotent PPO able to oxidize substrates characteristics of both tyrosinase and laccase (18, 34) and an SDS-activated tyrosinase. To explore their respective cellular functions and the structures of these enzymes, we needed to develop methods for detecting mutants affected differentially in both PPOs.

The detection of the SDS-activated tyrosinase can be easily done by checking the melanization of the colony (36). Using that method, we have already detected ng56 and some other amelanotic mutants lacking that activity but still expressing the multifunctional PPO. We now present a rapid test for this activity in agar plates containing DMP. According to this test, the wild-type and the mutant ng56 strains showed no differences, indicating that tyrosinase is not involved in the DMP oxidation. However, the test has proven to be an effective method for the detection of the laccase-lacking mutants, such as ngd67 and others, that had lost multipotent PPO activity but which were still able to synthesize melanins.

A systematic transposon mutagenesis of M. mediterranea with the mini-Tn10 transposons encoding gentamycin resistance allowed us to clone the multipotent PPO gene. This technique has already been used in the study of other marine bacteria (1, 39). Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA revealed that the transposition was a single event on the bacterial chromosome. However, the randomness of the insertion is uncertain, since after screening thousands of mutant strains, only one (Tn101) affected in the multifunctional PPO was found, and no amelanotic mutants phenotypically similar to ng56 and presumably affected in the SDS-activated tyrosinase gene have been so far detected. Further rounds of mutagenesis are underway to assess this point.

M. mediterranea Tn101 was obtained by using pBSL182. Marker rescue experiments allowed the cloning and characterization of the gene in which the gentamycin resistance marker was inserted. These data support the existence of two different PPOs encoded at different loci. The strains Tn101 and ngd67 are specifically affected in the multipotent membrane-bound PPO as shown by direct enzymatic activity measurements (Table 3) and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis staining (Fig. 1). The site of the transposon insertion easily accounts for this phenotype, as two characteristic copper centers of laccases (Table 4, columns C and D) are lost either by transposon insertion (Tn101) or by a premature stop codon (ngd67). In contrast, their cellular extracts maintained the SDS-activated oxidation of tyrosine and dopa. These strains are pigmented, indicating that the SDS-activated tyrosinase is the only PPO activity required for pigmentation. This point is important, since laccase activity has been involved in the melanization of A. lipoferum (17) and in the formation of fungal dihydroxynaphthalene-melanins (15). In contrast, our data support most of the bacterial strains so far studied, where l-tyrosine is the most common substrate for melanization and tyrosinase has been linked to this process (27, 32).

The protein sequence of PpoA revealed a signal peptide that it is very likely involved in its transport to the membrane (30). The mature protein remains bound to the membrane rather than released to the periplasmic space, and it is released by lipase treatment of membrane preparations (18), supporting the existence of a covalent link. Although the position for the hydrolysis site of the signal peptide will remain uncertain until direct sequencing of the N terminus of the purified mature protein, cleavage after 25A would permit the preservation of 26C in the N terminus, which would also allow for the anchoring of the protein to the membrane through a thioester bond, as a prokaryotic membrane lipid attachment protein (prosite PDOC00013 [20]).

The ppoA gene from M. mediterranea shows the four characteristic copper centers for laccases and other blue-copper proteins, but the similarity scores of ppoA from M. mediterranea with fungal laccases are quite low (around 40) (38). This fact accounts for the negative results obtained in all of our previous attempts to clone the multipotent laccase-like PPO gene by using genes from related PPO, such as prokaryotic tyrosinases or fungal laccases, to probe genomic digested DNA (10). In turn, PpoA differs from typical laccases in that it has cresolase activity, oxidizing l-tyrosine and other related monophenols that are specific substrates of tyrosinase. Further studies will be necessary in order to clarify the relationship between the presence of additional copper-binding domains and the range of substrates for this PPO. The histidine-containing motifs (HQTDHASH) occurring in the amino termini of ppoA or the HHNH cluster sited between amino acids 167 and 170 could be involved in its unique multifunctional catalytic properties. Directed mutagenesis studies are planned in the near future to correlate the presence of those binding copper sites with the enzymatic activities.

The prokaryotic blue-multicopper proteins constitute a group of proteins with different functions whose putative PPO activities have not been profoundly studied. Streptomyces phenoxazinone synthase is involved in antibiotic synthesis (22), CotA is expressed during the sporulation of Bacillus (14), the proteins from Pseudomonas syringae and Xanthomonas campestris are involved in copper resistance (24, 26), and there are other hypothetical proteins proposed from the systematic genomic sequencing of strains such as E. coli (8) and Aquifex aoelicus (11) without known function. Other, still uncloned, laccases have been found to be involved in other functions, as is the laccase from A. lipoferum, which is under the same control as the synthesis of components of the respiratory chain (2). At this point, the physiological role of the PpoA protein from M. mediterranea is unclear. The comparison of PpoA with other bacterial blue-multicopper proteins using the BLAST 2 Sequences (38) shows that the alignment score is significant, but low (Table 5). It is tempting to speculate that PpoA may be involved in some kind of response to stress conditions, since its expression is induced during the stationary phase of growth (18). This work has shown that M. mediterranea is amenable to genetic manipulation. The characterization of the mutant strain Tn101 in comparison with the wild type is in progress, but it has not yet revealed any phenotypic alteration except the loss of the multipotent PPO activity. Hopefully, the combination of different approaches will help to clarify the physiological role of this unique PPO, as well as its possible relationship with the SDS-activated tyrosinase responsible for melanin pigmentation.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of bacterial multicopper proteinsa

| Protein | Alignment score with

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECH | AAH | PSS | BCotA | PCR | XCR | |

| PpoA | 79.6 | 55.8 | 49.6 | 44.9 | 34 | 32.8 |

| ECH | 179 | 109 | 122 | 79.2 | 55.4 | |

| AAH | 116 | 161 | 52.7 | 42.2 | ||

| PSS | 267 | 36 | 33.2 | |||

| BCotA | 41.8 | 46.9 | ||||

| PCR | 774 | |||||

Alignment scores obtained for the different prokaryotic blue multicopper proteins using the program BLAST 2 Sequences (38). PCR, copper resistance factor from P. syringae; XCR, copper resistance, X. campestris; ECH, hypothetical protein, E. coli; PSS, phenoxazinone synthase, S. antibioticus; AAH, hypothetical protein, A. aoelicus; BCotA, sporulation protein, B. subtilis; PpoA, multipotent PPO, M. mediterranea.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant PB97-1060 from the CICYT, Spain. P. Lucas-Elío and E. Fernández were recipients of predoctoral fellowships from, respectively, Séneca Foundation (Comunidad Autónoma de Murcia) and Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Spain.

We are grateful to R. Santamaría, J. Olivares, M. Alexeyev, V. de Lorenzo, S. Kjelleberg, and T. D. Connell for providing bacterial strains and plasmids and to J. C. García-Borrón for helpful suggestions. We also thank the DNA sequencing service of CIB, Madrid, Spain, for their excellent and rapid work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertson N A, Stretton S, Pongpattanakitshote S, Östling J, Marshall K C, Goodman A E, Kjelleberg S. Construction and use of a new vector/transposon, pLBT::mini-Tn10:lac:kan, to identify environmentally responsive genes in a marine bacterium. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;140:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(96)00196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexandre G, Bally R, Taylor B L, Zhulin I B. Loss of cytochrome c oxidase activity and acquisition of resistance to quinone analogs in a laccase-positive variant of Azospirillum lipoferum. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6730–6738. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6730-6738.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexeyev M F, Shokolenko I N. Mini-Tn10 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis and gene delivery into the chromosome of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1995;160:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00141-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexeyev M F, Shokolenko I N, Croughan T P. New mini-Tn5 derivatives for insertion mutagenesis and genetic engineering in Gram-negative bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:1053–1055. doi: 10.1139/m95-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagdasarian M, Lurz R, Rückert B, Franklin F C H, Bagdasarian M M, Frey J, Timmis K N. Specific purpose plasmid cloning vectors. II. Broad host range, high copy number, RSF1010-derived vectors, and a host-vector system for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene. 1981;16:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belas R, Mileham A, Simon M, Silverman M. Transposon mutagenesis of marine Vibrio sp. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:890–896. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.3.890-896.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg C M, Berg D E, Groisman E A. Transposable elements and the genetic engineering of bacteria. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 879–925. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coll P M, Tabernero C, Santamaría R, Pérez P. Characterization and structural analysis of the laccase I gene from the newly isolated lignolytic basidiomycete PM1 (CECT 2971) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4129–4135. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4129-4135.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connell T D, Matone A J, Holmes R K. A new mobilizable cosmid vector for use in Vibrio cholerae and other Gram− bacteria. Gene. 1995;153:85–87. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00804-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deckert G, Warren P V, Gaasterland T, Young W G, Lenox A L, Graham D E, Overbeek R, Snead M A, Keller M, Aujay M, Huber R, Feldman R A, Short J M, Olson G J, Swanson R V. The complete genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. Nature. 1998;392:353–358. doi: 10.1038/32831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in Gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lorenzo V M, Timmis K N. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in Gram-negative bacteria with Tn-5 and Tn-10-derived mini-transposons. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:386–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan W, Zheng L B, Sandman K, Losick R. Genes encoding spore coat polypeptides from Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edens W E, Goings T G, Dooley D, Henson J M. Purification and characterization of a secreted laccase of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3071–3074. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.7.3071-3074.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eggert C, Temp U, Eriksson K E L. The ligninolytic system of the white rot fungus Pycnoporus cinnabarinus: purification and characterization of the laccase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1151–1158. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1151-1158.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faure D, Bouillant M L, Bally R. Isolation of Azospirillum lipoferum 4T Tn5 mutants affected in melanization and laccase activity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3413–3415. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3413-3415.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernández E, Sanchez-Amat A, Solano F. Location and catalytic characteristics of a multipotent bacterial polyphenol oxidase. Pigm Cell Res. 1999;12:331–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1999.tb00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Givaudan A, Effosse A, Faure D, Potier P, Bouillant M L, Bally R. Polyphenol oxidase from Azospirillum lipoferum isolated from rice rhizosphere: evidence for laccase activity in non-motile strains of Azospirillum lipoferum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;108:205–210. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi S, Wu H C. Lipoproteins in bacteria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1990;22:451–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00763177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in Gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh C J, Jones G H. Nucleotide sequence, transcriptional analysis, and glucose regulation of the phenoxazinone synthase gene (phsA) from Streptomyces antibioticus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5740–5747. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5740-5747.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber M, Lerch K. The influence of copper on the induction of tyrosinase and laccase in Neurospora crassa. FEBS Lett. 1987;219:335–338. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee Y A, Hendson M, Panopoulos N J, Schroth M N. Molecular cloning, chromosomal mapping, and sequence analysis of copper resistance genes from Xanthomonas campestris pv. juglandis: homology with small blue copper proteins and multicopper oxidase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:173–188. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.173-188.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansur M, Suárez T, Fernández-Larrea J B, Brizuela M A, González A E. Identification of a laccase gene family in the new lignin-degrading basiodiomycete CECT 210197. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2637–2646. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2637-2646.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mellano M A, Cooksey D A. Nucleotide sequence and organization of copper resistance genes from Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2879–2883. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2879-2883.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercado-Blanco J, Garcia F, Fernandez-Lopez M, Olivares J. Melanin production by Rhizobium meliloti GR4 is linked to nonsymbiotic plasmid pRmeGR4b: cloning, sequencing and expression of the tyrosinase gene mepA. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5403–5410. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5403-5410.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Messerschmidt A, Huber R. The blue oxidases, ascorbate oxidase, laccase and ceruloplasmin. Modelling and structural relationships. Eur J Biochem. 1990;187:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore B M, Flurkey W H. Sodium dodecyl sulfate activation of a plant polyphenoloxidase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4982–4988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pomerantz S H. The tyrosine hydroxylase activity of mammalian tyrosinase. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pomerantz S H, Murthy V V. Purification and properties of tyrosinases from Vibrio tyrosinaticus. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1974;160:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(74)80010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E J, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez-Amat A, Solano F. A pluripotent polyphenol oxidase from the melanogenic marine Alteromonas sp. shares catalytic capabilities of tyrosinases and laccases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:787–792. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon R, Quandt J, Klipp W. New derivatives of transposon Tn5 suitable for mobilization of replicons, generation of operon fusions and induction of genes in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1989;80:161–169. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solano F, García E, Pérez de Egea E, Sanchez-Amat A. Isolation and characterization of strain MMB-1 a novel melanogenic marine bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3499–3506. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3499-3506.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solano F, Sanchez-Amat A. Studies on the phylogenetic relationships of melanogenic marine bacteria. Proposal of Marinomonas mediterranea sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:1241–1246. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-3-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tatusova T A, Madden T L. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:247–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Techkarnjanaruk S, Pongpattanakitshote S, Goodman A E. Use of a promoterless lacZ gene insertion to investigate chitinase gene expression in the marine bacterium (Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain S) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2989–2999. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.2989-2996.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thurston C F. The structure and function of fungal laccases. Microbiology. 1994;140:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittenberg C, Triplett E L. A detergent-activated tyrosinase from Xenopus laevis. I. Purification and partial characterization. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:12535–12541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida H. Chemistry of lacquer (Urushi) part I. J Chem Soc. 1883;43:231–237. [Google Scholar]