Abstract

Background:

Silvery Hair Syndromes (SHS), an autosomal recessive inherited disorder, includes Chediak–Higashi syndrome (CHS), Griscelli syndrome (GS), Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome (HPS), and Elejalde syndrome. Associated immunological and neurological defects and predilection for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) makes them a distinctive entity in pediatric practice. Thorough clinical examination, bedside investigations such as peripheral blood smear (PBS) and hair microscopy, and bone marrow (BM) examination are inexpensive and reliable diagnostic tools.

Methods:

We report 12 cases with SHS (CHS, n = 06; GS, n = 04; HPS, n = 02).

Results:

8 out of 12 SHS children (CHS-05, GS-03) presented with HLH. Out of 5 cases of CHS with HLH, 2 died, 3rd is stable post-chemotherapy; 4th completed chemotherapy, underwent matched related hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), and is stable 8 months off treatment. The 5th child completed chemotherapy and is in process of transplant. One CHS child without HLH is thriving without any treatment. Of the 4 GS cases, 3 presented with HLH and received chemotherapy (HLH 2004 protocol). One lost follow-up after initial remission; another had recurrence 7 months off treatment and discontinued further treatment. The third child had recurrence 1.5 years after initial chemotherapy; HLH 2004 protocol was restarted followed by HSCT from matched sibling donor; is currently well, 2.5 years post-transplant. One child with GS had neurological features with no evidence of HLH and did not take treatment. Of 2 children with HPS, one presented with severe sepsis and the other with neurological problems. They were managed symptomatically.

Conclusion:

In SHS with HLH, chemotherapy followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a promising curative option.

KEY WORDS: Chediak–Higashi syndrome, Griscelli syndrome, hair examination, Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome, peripheral blood smear, silvery hair

Introduction

The presence of silvery hair in children can indicate underlying autosomal recessive disorders such as Chediak–Higashi syndrome (CHS), Griscelli syndrome (GS), Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome (HPS), and Elejalde syndrome. Pigmentary dilution, partial oculo-cutaneous albinism, immunological defects, increased susceptibility to pyogenic infections, and bleeding tendency are the characteristic features that may overlap, making the diagnosis difficult. Investigations such as a peripheral blood smear (PBS), bone marrow (BM), and light microscopy of the hair shaft are simple and reliable diagnostic tools. Polarized microscopy of hair shaft that uses refractive properties of keratin helps differentiate these syndromes. An evaluation for immune dysfunction is required for appropriate treatment of silvery hair syndrome (SHS).

We report SHS in children diagnosed using simple bedside investigations such as PBS, hair examinations, and other tests such as BM examination and genetic analysis.

Methodology

This case series includes 12 children with SHS diagnosed between June 2013 and March 2021 in a tertiary care pediatric center. Clinical findings provided leading clues, while PBS, BM, light, and polarized microscopy of hair substantiated the diagnosis. The outcome was assessed during the follow-up for a mean duration of 12 months. Written informed consent was taken from the respective parents for the scientific publication.

Description

Twelve children, aged 13 days–12 years with a median of 4 years were studied. The male:female ratio was 1:3. All had history of consanguinity and common clinical features, i.e., fever, silvery hair, and organomegaly with underlying genetic disorders [CHS (n = 06), GS (n = 04), and HPS (n = 02)]. Eight of 12 (66.66%) presented with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) at the time of diagnosis (GS 03; CHS 05). Photosensitivity was reported in 7 patients (CHS 05; HPS 02), and nystagmus in 4 (CHS 02; GS 01; HPS 01). Table 1 details the summary of cases. Figures 1-4 illustrate the salient features seen in our patients (Supplementary Figure (1,001.5KB, tif) : diagnosis of HPS).

Table 1.

Characteristic features of children with silvery hair syndrome described in this case series (Original)

| Patient characteristics | Chediak-Higashi syndrome | Griscelli syndrome | Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Case 9 | Case 10 | Case 11 | Case 12 | |

| Age | 4 y | 2 y | 6 y | 4 y | 6 y | 8 y | 2 m | 45 d | 13 d | 12 y | 5 y | 2 y |

| Sex (M/F) | F | F | F | F | M | F | M | M | F | F | F | F |

| Consanguinity degree | 2nd | 2nd | 3rd | 2nd | 3rd | 3rd | 3rd | 3rd | 2nd | 3rd | 3rd | 2rd |

| Clinical features (Fever, Organomegaly, rash) | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| *Albinism | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| *Silvery Hair | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| *Photosensitivity | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| *Nystagmus | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | + |

| *Bi/Pancytopenia | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - |

| *High ferritin | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - |

| *High | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | |

| Triglycerides | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - |

| *Bone Marrow | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| HLH evidence | - | |||||||||||

| *Mononuclear-cell inclusion bodies | + | |||||||||||

| Genetic Mutation | LYST | - | - | - | - | LYST | - | - | RAB 27A | RAB 27A | AP3B1 | AP3B1 |

| Treatment protocol | HLH 2004 | - | HLH 2004. | HLH 2004 | HLH 2004, HSCT | HLH 2004, HSCT | HLH 2004 | HLH 2004 | HLH 2004, HSCT | - | - | - |

| Follow-up | Died | Doing well | Died | Lost to follow-up | Doing well post HSCT | HSCT ongoing | Lost to follow-up | Doing well | Relapsed well post HSCT | Lost to follow-up | Doing well | Neuro-disability |

Figure 1.

Chediak–Higashi syndrome. Hyperpigmented small patches under the eyes. Silvery gray hair on the scalp and mottled pigmentation present over the face and the extremities. (Original)

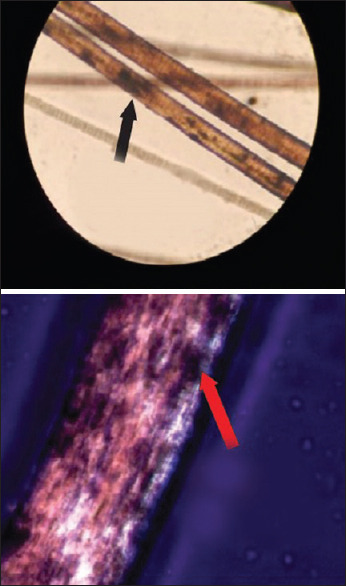

Figure 4.

Light microscopy showing giant melanosomes clumped irregularly in the medulla of the hair shaft. Polarized microscopy showing bright hair shaft with monotonous white appearance. (Original)

Figure 2.

Sparse silvery hair on the eyebrows and scalp of children with Griscelli syndrome. (Original)

Figure 3.

Chediak–Higashi syndrome. Silvery gray hair on the scalp. (Original)

The diagnosis was based on clinical presentation, signs, and laboratory evaluation (PBS, hair microscopy, and BM examination). Genetic testing was done in 6, and all were positive for characteristic gene mutation (GS 02; CHS 02, and HPS 02). Tests for immune function were done for 7 patients (CHS-4, GS-2, and HPS-1) and were normal in all.

The characteristic feature of CHS, i.e., large red inclusion-like granules in the cytoplasm of granulocytes, and lymphocytes were present in PBS and BM smear in all children with CHS. In 4/6 cases, light microscopy of hair showed regular and evenly distributed clumps of melanin pigment suggestive of CHS; 5/6 cases had HLH, who were treated as per the HLH 2004 chemotherapy protocol, which includes dexamethasone, etoposide, and ciclosporin, along with supportive care. Of the 5 CHS cases with HLH, one child completed chemotherapy, underwent matched related donor HSCT, and is stable off treatment. One child completed chemotherapy and is in the process of transplant. One child treated with chemotherapy, showed an initial response, and then lost follow-up (LFU). Two patients died; the cause of death was nonresponse to treatment with disease progression in one and recurrence post-chemotherapy in the other who had opted out of further treatment. One CHS child without HLH did not require any form of treatment.

Light microscopy of hair showed large irregular clumps of melanin granules in all GS children (4/4). Polarized microscopy of hair was done in one case where light microscopy was inconclusive; it showed a bright hair shaft with a monotonous white appearance suggestive of type 2 GS. Genetic mutation was confirmed in 2 cases {RAB 27A mutation (MIM #607624)}. Three out of 4 cases had evidence of HLH and were started on HLH 2004 treatment protocol.[1] Among them, one was LFU after initial remission; one had recurrence 7 months off treatment and did not pursue further treatment. The third child had recurrence 1.5 years after the initial chemotherapy, for which therapy was restarted (HLH 2004 protocol) and HSCT from a matched sibling donor was done. This child is currently doing well 2.5 years post-transplant. One GS case, who had neurological symptoms such as ataxia, nystagmus, dysphasia, and neuroregression with no evidence of HLH, did not go for any treatment for personal reasons.

Two children were diagnosed to have HPS; one presented with recurrent episodes of infection, short stature, and pancytopenia. Lymphocyte subsets and serum immunoglobulins were normal, while BM showed mildly reduced cellularity (45%). Other child had recurrent seizures refractory to antiepileptic drugs and ketogenic diet. BM examination was normal. Genetic sequencing showed mutation in the AP3B1 gene (MIM #603401) suggestive of HPS. Both children are stable on follow-up.

Discussion

Presence of silvery hair in children and neonates, particularly in a population with predominantly dark hair, is an uncommon manifestation and alarms the possibility of underlying systemic diseases.

Chediak–Higashi syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder, presents with pigment dilution, silvery hair, recurrent infections, hematological and progressive neurological manifestations. Though first described in 1943, it is still a poorly understood disease.[2] Prenatal diagnosis can be made by large acid phosphatase positive lysosomes in amniotic fluid cells, chorionic villus cells, or fetal blood leucocytes.[3]

The mean age of disease onset is 5–6 years (mean age of onset in our study is 4 years), and most children die before the age of 10 years.[4,5] The outcome in these patients is poor due to associated hemorrhage or infections. There is a possibility of relapse after chemotherapy in the exacerbation phase. Delayed diagnosis is associated with poor prognosis and lower success rate of BM transplantation; thus, identification of early signs and thorough investigation is vital for better outcomes.

PBS examination helps in differentiating CHS from other syndromes; presence of characteristic giant granules in leucocytes is the clinching diagnostic feature in PBS and BM smear.[6,7] Regular clumps of melanin pigment on light microscopy and a polychromatic appearance on polarized microscopic examination of hair shaft are seen in CHS.[6,7] The diagnosis can be confirmed by genetic studies (mutation in LYST/CHS1 gene on chromosome 1q42-43).

50%–85% of CHS patients have HLH.[3,4] In our series, out of 6 children with CHS, 5 had HLH; 3 are stable after treatment. Two children died as they did not undergo HSCT. One child without evidence of HLH is doing well without treatment and is being followed up. Our outcome is in concordance with previous reports, supporting the poor outcome in CHS with HLH.[3,4]

Griscelli syndrome's characteristic distinguishing feature is partial albinism and it is sub-classified into three types: associated neurological manifestations (GS1 - MYO5A mutation), with HLH (GS2- RAB27A mutation), and only hair and skin involvement (GS3- MLPH mutation). Hair shaft microscopy shows large irregular clumps of melanin in the medulla and a monotonous white appearance under polarized light. Treatment options differ, with specific treatment in the form of HSCT for type 2 and immune-modulation in case of significant CNS disability for type 1; no specific therapy is required for type 3.[8]

There are very few reported cases of GS (<100) worldwide, of which type 2 is most common. In our series, all four GS are of type 2, three with HLH and one with neurological symptoms only. HSCT is the primary treatment option to prevent mortality in GS with frank HLH as evidenced by previous reports and supported by our study as well.[9,10]

Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome is a rare disease that displays genetic heterogeneity; there are nine known subtypes.[11] It is characterized by oculo-cutaneous albinism, platelet storage-pool deficiency, and resultant bleeding diathesis. The storage-pool defect arises from the absence of platelet dense bodies, which contain adenosine diphosphate, adenosine triphosphate, calcium, and serotonin.[12] Patients with HPS demonstrate easy bruising and prolonged bleeding after surgical procedures. The ocular findings include reduced iris pigment with iris transillumination, decreased retinal pigment, foveal hypoplasia with a significant reduction in visual acuity (usually in the range of 20/50–20/400), nystagmus, and increased crossing of the optic nerve fibers. The accumulation of ceroid lipofuscin, an amorphous lipid-protein complex, is associated with pulmonary fibrosis[13] and granulomatous colitis. Neurological manifestations include early-onset seizures and developmental delay.[14] Of the 2 children with HPS, one is doing well on follow-up, while the other has neuro-disabilities.

In our center, of 12 children with SHS, there were 2 deaths and 3 were lost to follow-up. The remaining 7 patients are on regular follow-up and are clinically stable.

Elejalde syndrome (Neuroectodermal melano-lysosomal disease) is a rare type of silvery hair syndrome that needs to be differentiated from CHS and GS. It is characterized by silvery hair and severe CNS dysfunction without any immune dysfunction. Large granules of melanin unevenly distributed in hair shaft, abnormal melanocytes, melanosomes, and abnormal inclusion bodies in fibroblasts may be present.

Other differentials for SHS include Waardenburg syndrome and oculo-cutaneous albinism (type 1–4), which are easily distinguishable clinically as they are not associated with HLH or Immunodeficiency.

Whenever children with silvery hair are encountered in clinical practice, it should raise a high index of suspicion of underlying syndromic association, cytopenias, and immunological disorders. Hair shaft examinations, PBS, and BM are simple bedside investigations but are robust diagnostic tools. These syndromes have a good outcome if diagnosed and managed on time. Early, prompt intervention is required for effective management.

What this study adds

Adds to the existing knowledge pool about the diagnosis and management of silvery hair syndrome in children.

Meticulous clinical examination, simple bedside investigations (e.g., peripheral blood smear and hair microscopy), and bone marrow examination are inexpensive and reliable diagnostic tools in a limited resource setting.

In children with SHS and HLH, chemotherapy followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a promising curative option. Chemotherapy alone may not sustain remission. Lost to follow-up pose a challenge.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Diagnosis of Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. M. S. Latha, Consultant (Pediatric Research and Medical education), Rainbow Children's Hospital and Birthright, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad, India, for writing assistance.

References

- 1.Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124–31. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valente NYS, Machado MCMR, Boggio P, Alves AC, Bergonse FN, Casella E, et al. Polarized light microscopy of hair shafts aids in the differential diagnosis of Chediak-Higashi and Griscelli-Prunieras syndromes. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2006;61:327–32. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322006000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghaffari J, Rezaee SA, Gharagozlou M. Chédiak-Higashi syndrome. J Pediatr Rev. 2013;1:80–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maaloul I, Talmoudi J, Chabchoub I, Ayadi L, Kamoun TH, Boudawara T, et al. Chediak-Higashi syndrome presenting in accelerated phase: A case report and literature review. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2016;9:71–5. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinaver MC, Newburger P. The phagocyte system and disorders of granulopoiesis and granulocyte function. In: Orkin SH, Nathan DG, Ginsburg D, editors. Nathan and Oski's Hematology of Infancy and Childhood. 7th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2009. p. 1169. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahana M, Sacchidanand S, Hiremagalore R, Asha GS. Silvery grey hair: Clue to diagnose immunodeficiency. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:83–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.96910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy RR, Babu BM, Venkateshwaramma B, Hymavathi Ch. Silvery hair syndrome in two cousins: Chediak-Higashi syndrome vs Griscelli syndrome, with rare associations. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:107–11. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.90825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meschede IP, Santos TO, Izidoro-Toledo TC, Gurgel-Gianetti J, Espreafico EM. Griscelli syndrome-type 2 in twin siblings: Case report and update on RAB27A human mutations and gene structure. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2008;41:839–48. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2008001000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minocha P, Choudhary R, Agrawal A, Sitaraman S. Griscelli syndrome subtype 2 with hemophagocytic lympho-histiocytosis: A case report and review of literature. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2017;6:76–9. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2016.01084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pachlopnik Schmid J, Moshous D, Boddaert N, Neven B, Cortivo LD, Tardieu M, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Griscelli syndrome type 2: A single-center report on 10 patients. Blood. 2009;114:211–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-207845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seward SL, Jr, Gahl WA. Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: Healthcare throughout life. Pediatrics. 2013;132:153–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alcid J, Kim J, Bruni D, Lawrence I. A rare case of Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type 3. J Hematol. 2018;7:76–8. doi: 10.14740/jh387w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter BW. Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome complicated by pulmonary fibrosis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2012;25:76–7. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2012.11928790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ammann S, Schulz A, Krägeloh-Mann I, Dieckmann NMG, Niethammer K, Fuchs S, et al. Mutations in AP3D1 associated with immunodeficiency and seizures define a new type of Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Blood. 2016;127:997–1006. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-671636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Diagnosis of Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome