Abstract

Shared book reading is a well-established vehicle for promoting child language and early development. Yet, existing shared reading interventions have primarily included only children age 3 years and older and high quality dialogic strategies have been less systematically applied for infants and toddlers. To address this gap, we have developed a book-sharing intervention for parents of 12- to 36-month-olds. The current study evaluated acceptability/usability and preliminary efficacy of book-sharing intervention in a randomized controlled trial. Parent-child dyads were randomized to either 8-week book-sharing intervention (n=15) or wait list control (n=15). Parent book-sharing skills were assessed at baseline, post-intervention, and 2-month follow-up. Results indicated parents found the intervention highly acceptable and useful. Parents receiving intervention demonstrated significant improvement in book-sharing strategies compared to controls at post-intervention and 2-month follow-up. The current study provides evidence for the benefit of a brief, low intensity, targeted intervention to enhance parent book-sharing with infants and toddlers.

Keywords: shared reading, book-sharing, reading, language, attention, parent-child interaction, parent coaching, infant, toddler

Shared reading is a well-established vehicle for promoting language and literacy in early childhood (Hutton et al., 2015; National Early Literacy Panel, 2008; Hargrave and Senechal, 2000). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends sharing books with infants as soon as possible to promote healthy development (Council on Early Childhood et al., 2014). Shared reading can enhance the quality of the early language environment (Logan et al., 2019; Blewitt et al., 2009), which in turn predicts more optimal long-term academic, economic and health outcomes for all children (Biermiller and Slomin, 2001; Hart and Risley, 1995). Yet, the evidence-based dialogic reading approach to support parents’ high quality shared reading with preschool and school age children has not been broadly or systematically extended into the early years. The lack of focused intervention for parents of infants and toddlers is noteworthy, given the potential for enhancing early parent-child shared reading interactions and the benefits of shared reading for enhancing child outcomes.

Benefits of Shared Reading in Childhood

The positive effects of shared reading on child language are well-established (for meta-analyses see Dowdall et al., 2020; Bus et al., 1995; for reviews see Scarborough and Dobrich, 1994; National Early Literacy Panel, 2008). Shared reading provides powerful and salient opportunities for vocabulary acquisition, and even a single reading of a book can promote new word-learning (Senechal and Cornell, 1993). When parents add shared reading to their day (compared to non-reading days), it results in significantly more parent talk, child talk and high-quality language interactions (Clemens and Kegel, 2021). The frequency of early shared reading experiences accounts for vocabulary differences observed in preschoolers, even after controlling for parent education and literacy level (Senechal et al., 1996), with an overall effect size of d = 0.59 on language and literacy outcomes (Bus et al., 1995). In fact, frequency of shared reading as early as 6 months of age predicts more optimal vocabulary by 12 months (O’Farrelly et al., 2018). The benefits for child social-emotional competence are also increasingly recognized (Wirth et al., 2019; Murray et al., 1996). Although less examined, differences in quality of parent-child shared reading also predict later child vocabulary (Malin et al., 2014; DeBaryshe, 1995). For all of these reasons, shared reading is sometimes called a ‘vocabulary acquisition device’ (Ninio, 1983), prompting the development of interventions to enhance shared reading.

Targeted interventions that coach parents to use high-quality dialogic reading strategies with preschool and school age children follow the approach developed by Whitehurst and colleagues (Arnold and Whitehurst, 1994; Whitehurst et al., 1988) to foster active child participation and language interactions during book reading. Recent meta-analyses demonstrate this approach has a significant large effect on parents’ book-sharing competence and language facilitation/contingent responding and medium to large effects on improving child communication/language (Heidlage et al., 2020; Bus et al., 1995; Dowdall et al., 2020). Beyond language, theory and accumulating evidence demonstrate high quality shared reading yields broader benefits for enhancing child cognitive and attention skills (Whitehurst et al., 1994; Vally et al., 2015; Salley et al., 2017); social emotional outcomes (Yont et al., 2003; Murray et al., 2016); and preliteracy and school readiness (Theriot et al., 2003; Bus et al., 1995). In sum, there are many benefits of parent-implemented shared reading intervention for preschool/school age children and it is reasonable to expect the benefits may be similar for infants and toddlers, yet programs that target children younger than 3 years have been limited (Heidlage et al., 2020; Dowdall et al., 2020).

Book Sharing With Infants and Toddlers

Compared to book reading interactions with older children, the term “book-sharing” is used here to capture the nature of the experience with infants and toddlers. For preschool and school ages, the focus is on a book’s words, pictures and story; in contrast, for infants and toddlers the focus is first on establishing an engaging, language-rich context to create communication opportunities and engagement with the book (e.g., grabbing, patting, opening, chewing, turning pages) and pictures, rather than focusing on reading words on a page or having to complete the whole story in sequence (Ezell and Justice, 2005).

For infants and toddlers, the book-sharing context is a particularly powerful vehicle for language promotion. First, compared to other play and daily routines, book-sharing more reliably and naturally elicits parent’s use of joint attention and language facilitation strategies (Snow and Goldfield, 1983; Fletcher et al., 2005). Second, book-sharing is ideal for parent-implemented intervention – it is a concrete routine, which increases potential for successfully coaching parent skills; it provides high density practice opportunities for new skill acquisition for parent (to use book-sharing strategies) and child (to engage and respond to communication opportunities); and finally, it is well suited for reducing disparities in the early language environment (Vally et al., 2015; Logan et al., 2019).

The lack of targeted book-sharing intervention for infants and toddlers may be due to the greater focus on emerging literacy beginning at preschool age, together with a lack of systematic guidance in the literature for modifying dialogic strategies for infants/toddlers. Successful parent-implemented intervention requires teaching pre-requisite skills, instructing regularly, requiring mastery, and emphasizing broad generalization (Ellis et al., 1991). Yet, existing book-sharing interventions that include children younger than 3 years have included a limited number and type of parent skills, a lack of developmental sequencing of skills for the infant/toddler population, and a lack of structured implementation guidance for early childhood providers (Boyce et al., 2010; Buschmann et al., 2009). To provide maximal benefit, evidence-based dialogic strategies employed with preschool children must be modified and systematically structured to create an age-appropriate, engaging, shared reading experience that matches communication needs in the early years.

Notably, recent work by Cooper and colleagues provides strong evidence for the benefit of a relatively simple (low intensity/low cost) structured book-sharing intervention with high-risk families in South Africa, who had high rates of illiteracy and no culture of book-sharing with young children (Cooper et al., 2014; Murray et al., 2016; Vally et al., 2015). In a randomized trial, parents of 14- to 16-month-old infants participated in 8 small group sessions that provided instruction in specific book-sharing skills (child participation; pointing and naming; following child’s attention; active questioning; active linking). Intervention resulted in significant improvement in parent book-sharing skills, and in child language, attention and socioemotional outcomes. Importantly, this suggests the potential for a systematic, developmentally sequenced downward extension of dialogic strategies for infants/toddlers.

Developing Book Sharing Intervention for Parents of Infants and Toddlers

To extend existing dialogic reading approaches for preschool/school ages into infant/toddler years, we have developed Ready, Set, Share A Book! for parents of children 12- to 36-months-old. This manualized parent-training intervention is designed to be delivered by early childhood providers of varying disciplines and training backgrounds, working in a range of settings with parents of infants and toddlers (e.g., Part C, school or center-based programs, childcare, other professionals or paraprofessionals). The intervention incorporates evidence-based parent coaching practices routinely used with early intervention (Friedman et al., 2012), as described below.

The framework for Ready, Set, Share A Book! blends developmentally modified dialogic reading strategies for children 3- to 5-years-old with evidence-based language facilitation strategies for infants and toddlers (as illustrated in Table 1), and is adapted from the work of Cooper and colleagues in South Africa (Cooper et al., 2014; Murray et al., 2016; Vally et al., 2015). Dialogic reading is built on three over-arching principles (encourage child participation; provide feedback to child; adapt reading to child’s linguistic ability; Whitehurst et al., 1988), which we developmentally adapt by breaking into smaller, age-appropriate steps. From the language facilitation literature, we draw upon Milieu (MT) and Enhanced Milieu Teaching (EMT) to promote infant/toddler responsivity, language and attention (Kaiser and Trent, 2007; Kaiser and Roberts, 2013). Child participation is encouraged by aligning with MT/EMT strategies of following child lead and balancing turns (Kaiser, 1993). Child feedback is aligned with MT/EMT strategies of responding to child verbalizations (Baxendale and Hesketh, 2003), recasting child utterances (Kouri, 2005), and providing focused language stimulation (Girolametto et al., 1996). Child linguistic ability is matched by incorporating MT/EMT strategies of providing multiple word models and topically related language (Baxendale and Hesketh, 2003; Kaiser and Trent, 2007). Finally, specific book-sharing strategies are sequenced in a developmental order (early lessons incorporate foundational strategies for later skills), as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 1.

Alignment of Evidence-Based Dialogic Reading and Language Facilitation Strategies for Infants and Toddlers Within the Ready, Set, Share A Book! Intervention Approach

|

Table 2.

Ready, Set, Share A Book Overview and Parent Book sharing Skills

| Lesson | Component | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Follow Child Lead | Parent encouraged to support the child’s interest and active participation; to facilitate child’s handling of the book (help turn pages, steady, orient book). |

| Lively Voice | Parent encouraged to use engaging voice (change tone/pitch, sound effects, etc.). | |

| 2 | Naming/Pointing and Naming | Parent encouraged to point and name objects and actions in child’s visual field. |

| Praise and Positive Comments | Parent encouraged to praise child for participating in book-sharing. | |

| 3 | Naming and Repeating | Parent encouraged to name item/action and repeat at least lx. |

| Talking About Actions | Parent encouraged to name action and act it out. | |

| 4 | Elaborating | Parent encouraged to add descriptive information to a word already labeled. |

| Linking | Parent encouraged to make a connection between book content and child’s real-world experiences. With young children, linking to here and now (e.g., “there are baby’s toes, here are your toes”); with older children linking to wider experience (e.g. pictured dog is “just like the dog next door”). | |

| 5 | Asking Questions and Pausing | Parent encouraged to ask WH- question and pause for child response. For words child understands, ask child to point to object/action (e.g., “Where is the…?”). For words child says, ask questions like “What/Who is that?” and point to relevant picture. |

| 6 | Talking About Feelings | Parent encouraged to point out and talk about emotion content in the book (e.g., “The gorilla is crying. He is sad.”), using their own face/voice to convey emotions. |

| 7 | Rhyming and Pausing | Parent encouraged to pause during the rhyme and wait for child to fill-in-the-blank. |

| 8 | Review and Next Steps |

Adapted from Cooper et al. 2014.

The current study evaluates the feasibility and preliminary benefits of Ready, Set, Share A Book!. This first evaluation includes lower risk families (in community-based services through Parents As Teachers), to guide our next steps of extending the intervention to a broader range of at-risk and language delayed child populations. We examine the following specific questions: (1) whether parent-implemented book-sharing intervention would be evaluated as acceptable and useful by parents of infants/toddlers; (2) whether parents would demonstrate gains in high-quality (dialogic) book-sharing skills after participating in the intervention, compared to controls; and whether parent gains in book-sharing skills would be maintained at 2 month follow-up; and (3) an exploratory descriptive examination of whether families of different demographic characteristics benefit similarly from the intervention. This last question is exploratory given that the participating families were quite similar and largely college educated.

Methods

Participants and Randomization

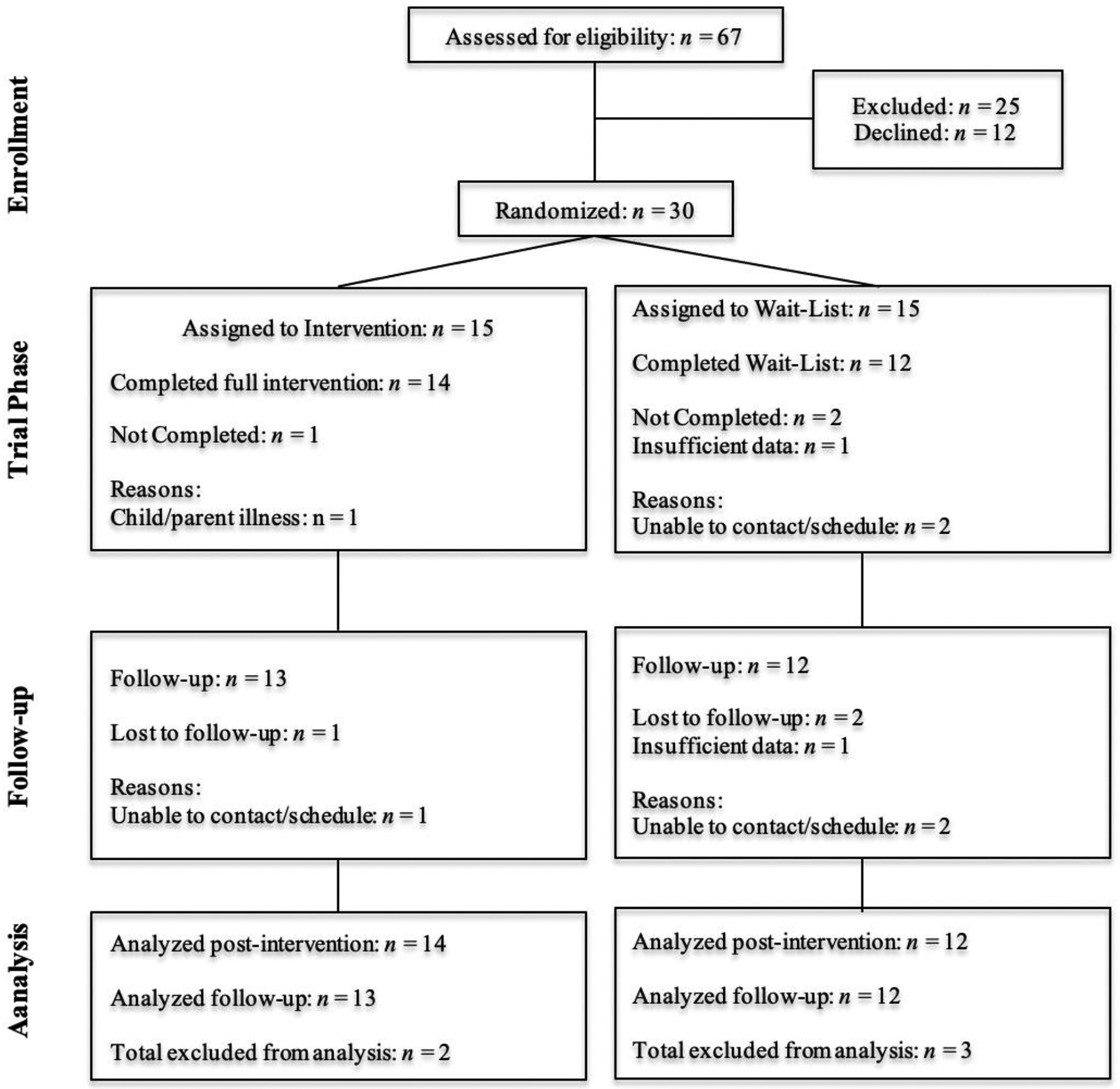

Parents and their infant/toddler (n=30) were recruited through Parents as Teachers (PAT), which targets families with high needs characteristics, but also includes low risk families. PAT offers home visits and center-based activities to provide parents with information about early development, learning and health, as well as developmental screenings and referrals for assessments. At enrollment in the study, children were between 14- and 19-months-old. All children were carried full-term (>36 weeks), able to participate in English, and without visual/hearing impairments. See Table 3 for demographics. At enrollment, dyads were randomized to Treatment (n=15) or Wait List Control Groups (n=15); see Figure 1. Control group families were invited to participate in the intervention after all follow-up assessments were completed. Child age during intervention (for both treatment and control groups) ranged from 14 to 22 months. One participant in the treatment group was removed from all final analyses due to attendance (fewer than 6 intervention sessions). Three participants were removed from the control group (2 did not attend post-intervention or follow-up assessments; 1 did not complete book-sharing at assessment). Written informed consent was obtained from parents prior to initiation of study activities. The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at the University of Kansas Medical Center (HSC #3704). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Kansas Medical Center (Harris et al., 2009).

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample at Baseline.

| Intervention (n=14) | Wait List Control (n=12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Age in Months (SD) | 15.7 (1. 4) | 15.9 (1.6) | t(24) = −.17, p=.87 |

| Range | 14–18 | 14–18 | |

| Child Sex ratio (M:F) | 10:4 | 8:4 | X2(1) = .07, p=.79 |

| Child Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 12 | 10 | z=.17, p=.87 |

| African American | 2 | 0 | z=1.36, p=.17 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 | 0 | |

| Multiple | 0 | 2 | z=1.59, p=.11 |

| Hispanic/Latino - Caucasian | 2 | 1 | z=.47, p=.64 |

| Maternal Age (years) | 32.2 (4.6) | 30.9 (4.9) | t(24) = .69, p=.50 |

| Maternal Education | |||

| High School/Some College | 7% | 33% | z=1.69, p=.09 |

| College | 71% | 33% | z=1.94, p=.052 |

| Graduate School | 21% | 33% | z=.68, p=.50 |

| Maternal Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 12 | 10 | z=.17, p=.87 |

| African American | 2 | 0 | z=1.36, p=.17 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 | 0 | |

| Multiple | 0 | 2 | z=1.59, p=.11 |

| Hispanic/Latino - Caucasian | 2 | 1 | z=.47, p=.64 |

| Home Language | |||

| English only | 71% | 75% | z=.20, p=.84 |

| Second language (>10% but less than 50%) | 29% | 25% | |

| StimQ-Toddler READ Scale Score (possible range 0–18) | 13.5 (2.3) | 14 (2.2) | t(24) = −.57, p = .71 |

| CSBS Total Standard Scores | 92.7 (12.8) | 97.7 (10.4) | t(24) = −1.1, p = .41 |

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram for trial.

Ready, Set, Share A Book! Intervention

Ready, Set, Share A Book! (Salley and Daniels, 2017) included education and coaching for parents on dialogic book-sharing over 8 sessions (45 min each) delivered weekly. This dosage and intensity are in line with book-sharing interventions for toddlers (Heidlage et al., 2020). Intervention was delivered in small-groups (4–5 dyads) in a community PAT playroom. Sessions were manualized and delivered by research assistant facilitators, trained (half-day instruction with role play and practice) and supervised by licensed providers (DD, BS). Facilitators led the same groups each week; families occasionally attended different groups (due to illness, family scheduling conflicts). Each session included group instruction (25–30 minutes) and individual coaching (5–10 minutes for each dyad; approximately 15 minutes to complete individual coaching sessions for the whole group).)Each group had 2–3 facilitors who co-led the group instruction and then provided coaching; during coaching time, families remained in the large playroom until their turn for a 1:1 session in individual breakout rooms. Parents took home the book of the week and a weekly guide card with tips/reminders for using book-sharing strategies.

Group instruction began with a check-in (i.e., What was your baby’s favorite part of the book?, What was the hardest part of book-sharing this week? etc.) to allow group encouragement and problem-solving. Group education (facilitated by PowerPoint) involved general information about development (e.g., early brain growth, pre-literacy, etc.), followed by introduction of a new book-sharing strategy (e.g., how to use the skill; why the skill is beneficial), with facilitator modeling with the book of the week, and video examples of parent-child dyads using the skill. Target skills are presented in Table 2.

Individual coaching was 1:1 with each parent-child dyad and a facilitator. Following the “Teach-Model-Coach-Review” approach (Roberts et al., 2014), the facilitator offered reinforcement, guidance and modeling to support skill learning and mastery. Facilitators coached at least 5 specific opportunities for parents to use the new skill and at least 5 opportunities for using previous skills. Facilitators used the following coaching strategies: reinforcing (praise) parent skill use; modeling skills for parent; and instructing the parent to use the skill. To examine fidelity of implementation, 33% of coaching sessions (across all facilitators) were randomly selected and coded offline by trained observers; facilitator fidelity was 88.4% for new skills and 85.7% for previous skills.

Evaluation Measures

All dyads visited the lab to complete assessments at baseline (1 week before treatment); post-intervention (1 week after treatment); and at 2-month follow-up (8 weeks after treatment).

Questionnaire Measures.

At baseline, parents completed a demographics questionnaire. The StimQ Preschool READ Scale (Dreyer et al., 1994) was completed to describe the home reading environment. To characterize child language level, parents completed the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile: Infant/Toddler Checklist (CSBS-DP; Wetherby and Prizant, 2002), a screening measure that yields a norm-referenced score indicating risk for communication impairment.

Parent Book Sharing Skills.

At each assessment visit, parents were asked to look at a book (Clap Hands by Helen Oxenbury) with their child for 5 min, just as they would if they were at home. Parent-child book-sharing was video recorded during assessment visits and during intervention coaching sessions. Interactions were coded offline by trained observers (blind to condition) for frequency of parent book-sharing skills (see Table 2) during the first 5 minutes of codable interaction; inter-rater reliability of coders k=.615.

Acceptability/Usability.

After participating in Ready, Set, Share A Book!, treatment group parents completed an anonymous online questionnaire (via Redcap). Parents rated perceived changes in their knowledge and ability to use book-sharing strategies and child engagement during book-sharing. See Table 4 for questionnaire.

Table 4.

Parent Experience (Acceptability/Usability) Survey

| Please answer each question about your experience. | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Why did you decide to participate? |

| 2. | Did you find this experience to be helpful for you and your child? |

| 3. | What did you find most helpful? |

| 4. | Would you recommend this experience to other families? |

| 5. | What suggestions do you have for improving the experience for other families? |

| 6. | Please describe any changes in how you approach book-sharing with your child. |

| 7. | Please describe any changes you have noticed in your child during book-sharing or as a result of book-sharing. |

|

Please rate each question after your participation

in Ready, Set, Share A Book! (0=No Change, 50=Some Improvement, 100=Significant Improvement) | |

| 8. | My understanding of the importance of book-sharing |

| 9. | My confidence in sharing books with my child |

| 10. | My knowledge and ability to share books with my child |

| 11. | My child’s interest in books (e.g., bringing books to parent, looking at books, etc.) |

| 12. | My child’s enjoyment with books |

| 13. | My child’s attention during book-sharing |

| 14. | My child’s participation in book-sharing (e.g., turning pages, pointing at pictures, vocalizing/words, etc.) |

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize parent acceptability/usability data to address research question one. Multilevel modeling (MLM) analyses were conducted using the MIXED procedure within SAS (9.4) to address research question two regarding differences in parent skill between groups. In these models, observations (Level-1 units) were nested within participants (Level-2 units). The repeated effect of time (baseline and post-intervention) was modeled in the first set to examine intervention effects. Similar models were evaluated for the effect of time (baseline and follow-up) to examine maintenance effects. Planned comparisons examined the simple effect of differences between groups at baseline, post-intervention, or follow-up. Planned comparisons examined simple effects across time within each group. The main analyses reported in this manuscript are completer analyses for those who attended at least 6 of the 8 treatment sessions, because our aim was to be conservative in our estimation of treatment effects within this relatively small pilot. Thus, our results are efficacy results, rather than effectiveness results, and provide information about the effectiveness of the intervention when implemented as intended. As a preliminary step towards a future examination of effectiveness, we examined intent to treat models and included three additional participants who only had baseline observations, and one participant who only attended 4 intervention sessions but had baseline and post-intervention data available. These intent to treat results are presented briefly in text and fully in Supplements 1 and 2. To determine if families with different demographic characteristics benefited from intervention, we examined change in total skill rates from week 1 to week 6 using paired-samples t-tests. It should be noted that larger changes are needed when sample sizes are smaller to be considered as a significant change. Descriptive summaries of skill rates over time were provided for demographic categories with very small sample sizes. Standardized mean differences were calculated for each group.

Results

Dyads in treatment and control groups were similar in terms of background and demographics (see Table 3). While the intervention group had a high percentage of participants with college degrees as compared with the waitlist control group, the difference was not statistically significant (p=.052). The proportion in each category of maternal education was not statistically significantly different across treatment conditions. Treatment dyads completed at least 6 of 8 sessions, except for 1 dyad which only attended 5 sessions and was excluded from analyses. We also ran intent to treat models with all available observations that were of sufficient length to be included. See Figure 1 for participant data for assessment visit completion.

Acceptability/Usability

Parents in the treatment group (n=14) were highly positive about the intervention, rating the experience as beneficial and helpful for their child and family (100% rated as 100 = “significant improvement”). All parents (100%) indicated they would recommend the experience to other families. Parent reasons for participating included: supporting child communication/development (64%); and providing a positive experience for their child (29%).

Parents rated their improvement in knowledge of the importance of book-sharing very highly, with a mean of 89.7 (SD=15) on a 100-point scale. Improvement in parent understanding ranged from 50 to 100, with 85% reporting “significant improvement” (> 80) in knowledge of importance of book-sharing with their child. Parents also rated gains in book-sharing confidence very highly, with a mean of 82.4 (SD=25). Improvement in confidence ranged from 17 to 100, with 71% reporting “significant improvement” (> 80) in their confidence in book-sharing with their child. Finally, parents rated gains in their ability to book-share with their child, which were also very positive with a mean of 84.9 (SD=14). Improvement in parent ability ranged from 67 to 100, with 71% reporting “significant improvement” (> 80).

Parents rated their child’s book-sharing gains after completing the intervention on a 100-point Likert scale (0 “no change”; 50 “some improvement”; 100 “significant improvement”). Parent responses indicated positive changes in child interest in books, with a mean of 72.6 (SD=20.2) and 36% reporting large improvement (> 80). Parent responses indicated positive changes in child enjoyment of books, with a mean of 76.08 (SD=21.1) and 43% reporting large improvement (> 80). Parents also reported positive change in child attention during book-sharing, with a mean of 79.2 (SD=17.8) and 64% reporting large improvement (> 80). Finally, parents rated their child’s participation during book-sharing, with a mean of 79.9 (SD=21.8) and 73% reporting large improvement (> 80).

Parent Book Sharing Gains

Parent book-sharing skills taught during intervention were individually examined at baseline, post-intervention, and follow-up. Total skill rate across all 12 skills (Table 5) was calculated for each occasion. Parents’ average rate (per minute) was calculated for each book-sharing skill.

Table 5.

Summary of Intervention Interaction Effects and Significant Simple Effects on Parent Skills

| Time × Condition | Baseline Simple Effect | Post-Intervention Simple Effect | Treatment Simple Effect | Control Simple Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow Child Lead | F(1,22)=.11, p=.75, d=.15 | F(1,22) = 4.55, p=.04, d=.71 | |||

| Lively Voice | F(1,22) = 3.35, p=.08, d=.89 | F(1,22) = 3.96, p=.06, d=.92 | F(1,22) = 7.90, p=.01, d=.97 | ||

| Naming | F(1,22) = 4.26, p=.05, d=.82 | F(1,22) = 6.06, p=.02, d=.70 | |||

| Pointing and Naming | F(1,22) = .07, p=.79, d=.15 | ||||

| Praise and Positive Comments | F(1,22) = .55, p=.47, d=.39 | F(1,22) = 3.02, p=.09, d=.71 | |||

| Naming and Repeating | F(1,22) = .15, p=.70, d=.32 | ||||

| Talking About Actions | F(1,22) = .64, p=.44, d=.31 | F(1,22) = 4.85, p=.04, d=.73 | |||

| Elaborating | F(1,22) = .01, p=.99, d=.01 | F(1,22) = 5.04, p=.04, d=.83 | F(1,22) = 5.49, p=.03, d=.83 | ||

| Linking | F(1,22) = 1.05, p=.32, d=.35 | F(1,22) = 6.27, p=.02, d=.84 | F(1,22) = 6.79, p=.02, d=.63 | ||

| Asking Questions | F(1,22) = 5.47, p=.03, d=1.65 | F(1,22) = 8.72, p < .01, d=1.55 | F(1,22) = 18.91, p< .001, d=2.14 | ||

| Rhyming and Pausing | Not modeled- 0 means | ||||

| Talking About Feelings | F(1,22) = .79, p=.38, d=.01 | ||||

| Total Skills (12) | F(1,22) = 3.75, p=.066, d=.79 | F(1,22) = 10.86, p=.003, d=1.25 | F(1,22) = 14.61, p=.0009, d=1.09 |

Intervention effects.

There were significant differences between groups for change in book-sharing skill use (significant time by condition interactions) from baseline to post-intervention for naming, F(1,22)=3.35, p=.05, and asking questions, F(1,22)=5.47, p=.03. Treatment parents increased naming from 1.22 times / minute on average at baseline to 1.77 times / minute at post-intervention; in comparison, control parents were relatively stable in rate of naming (average 1.26 and 1.16 / minute at baseline and post-intervention); see Table 6 for LS means. Control parents did not change significantly in their rates of any single skills from baseline to post-intervention (see Table 7, control group simple effects column). The treatment group increased significantly in their total skill use, F(1,22)=14.61, p=.0009, from 13.12 total skills / minute at baseline to 19.46 skills / minute at post-intervention. Specifically, treatment group parents increased significantly in following child’s lead, lively voice, naming, linking, and asking questions. The treatment group rate of skill use was significantly different from the controls at post-intervention for talking about/acting out actions, elaborating, linking, and asking questions (note, groups were not statistically significantly different at baseline in any skills, except for elaborating which treatment parents used somewhat more than controls).

Table 6.

Summary of Maintenance Interaction Effects and Significant Simple Effects on Parent Skills

| Time × Condition | Baseline Simple Effect | Maintenance Simple Effect | Treatment Simple Effect | Control Simple Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow Child Lead | F(121)=.36 p=.55, d=.26 | F(121)=4.02 p=.06, d=.61 | |||

| Lively Voice | F(121)=.77 p=.39, d=.31 | ||||

| Naming | F(121)=7.91 p=.01, d=1.33 | F(121)=11.49 p=.003, d=1.24 | F(121)=5.96 p=.02, d=.81 | ||

| Pointing and Naming | F(121)=.46 p=.50, d=.45 | F(121)=3.15 p=.09 d= .84 | |||

| Praise and Positive Comments | F(121)=.13 p=.72, d=.18 | F(121)=3.55 p=.07, d=.70 | |||

| Naming and Repeating | F(121)=.46 p=.50, d=.68 | F(121)=3.89 p=.06, d=1.03 | F(121)=5.33 p=.03, d= 1.22 | ||

| Talking About Actions | F(121)=.10 p=.76, d=.10 | ||||

| Elaborating | F(121)=6.10 p=.02, d=1.29 | F(121)=3.86 p=.06, d= .81 | F(121)=8.32 p=.01, d= 1.06 | ||

| Linking | F(121)=.31 p=.59, d=.23 | F(121)=5.06 p=.04, d= .75 | |||

| Asking Questions | F(121)=13.37 p=.002, d=2.36 | F(121)=16.39 p<.001, d=2.42 | F(121)=29.46 p< .001, d=2.49 | ||

| Rhyming and Pausing | F(121)=.94 p=.34, d*=.65 | F(121)=4.66 p=.04, d*=1.00 | |||

| Talking About Feelings | F(121)=.88 p=.36, d*=.63 | ||||

| Total Skills (12) | F(121)=2.93 p=.10, d=.71 | F(121)=8.46 p=.008, d=1.18 | F(121)=7.73 p=.011, d=.82 |

d* Uses pooled raw SD across all observations because baseline was all 0.

Table 7.

Intervention Least Squares Means and Standard Errors for Individual Parent Skills

| Baseline | Post-Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Group | Control Group | |||

| Follow Child Lead | .68 (.11) | .68 (.11) | .36 (.10) | .43 (.11) |

| Lively Voice | 1.60 (.48) | 1.56 (49) | 3.00 (.46) | 1.66 (.49) |

| Naming | 1.22 (.24) | 1.26 (.25) | 1.77 (.23) | 1.16 (.25) |

| Pointing and Naming | 1.53 (.35) | 1.49 (.35) | 1.85 (.33) | 1.96 (.35) |

| Praise/Positive Comments | .52 (.17) | .10 (.17) | .53 (.16) | .34 (.17) |

| Naming and Repeating | .40 (.18) | .27 (.18) | .72 (.17) | .47 (.18) |

| Talking About Actions | 2.09 (.37) | 1.44 (.38) | 2.52 (.35) | 1.39 (.38) |

| Elaborating | .98 (.20) | .35 (.20) | 1.09 (.18) | .46 (.20) |

| Linking | 2.45 (.48) | 1.48 (.490 | 3.71 (.46) | 2.03 (.49) |

| Asking Questions | 1.66 (.40) | 1.77 (.40) | 3.89 (.37) | 2.28 (.40) |

| Rhyming and Pausing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Talking About Feelings | < .0001 (.02) | < .0001 (.02) | .03 (.02) | < .0001 (.02) |

| Total Skills (12) | 13.12 (1.60) | 10.41 (1.63) | 19.46 (1.51) | 12.16 (1.63) |

| Maintenance Least Squares Means and Standard Errors for Individual Parent Skills | ||||

| Baseline | Follow-Up | |||

| Control Group | Control Group | |||

| Follow Child Lead | .67 (.11) | .68 (.11) | .51 (.11) | .40 (.11) |

| Lively Voice | 1.52 (.36) | 1.56 (.36) | 1.65 (.35) | 1.23 (.36) |

| Naming | 1.19 (1.21) | 1.26 (.21) | 1.84 (.20) | .85 (.21) |

| Pointing and Naming | 1.49 (.39) | 1.49 (.39) | 2.31 (.37) | 1.87 (.39) |

| Praise/Positive Comments | .53 (.16) | .10 (.16) | .62 (.16) | .30 (.16) |

| Naming and Repeating | .40 (.14) | .27 (.14) | .85 (.13) | .47 (.14) |

| Talking About Actions | 2.08 (.35) | 1.44 (.36) | 1.87 (.34) | 1.07 (.36) |

| Elaborating | .97 (.22) | .35 (.22) | .80 (.22) | 1.17 (.22) |

| Linking | 2.54 (.49) | 1.48 (.49) | 3.32 (.47) | 1.80 (.49) |

| Asking Questions | 1.83 (.43) | 1.77 (.43) | 4.32 (.41) | 1.90 (.43) |

| Rhyming and Pausing | < .0001 (.02) | < .0001 (.02) | .05 (.01) | .02 (.02) |

| Talking About Feelings | < .0001 (.02) | < .0001 (.02) | .05 (.02) | < .0001 (.02) |

| Total Skills (12) | 13.26 (1.73) | 10.41 (1.76) | 18.14 (1.68) | 11.07 (1.76) |

Intervention Effects in Intent to Treat Analysis.

The addition of the additional cases influenced the time by condition interaction for one individual skill, use of lively voice. In the completers analysis, this effect was not statistically significant, p=.08, but in the completers efficacy analysis this effect was significant, p=.03 with treatment parents increasing this skill while control parents did not. Additionally, the time by condition interaction for parents’ total rate of using of book-sharing skills was significant in the ITT analysis p=.01, as compared to p=.066 in the completers models.

Maintenance Effects.

There were significant differences in changes from baseline to maintenance between groups in naming, elaborating, and asking questions. Treatment parents increased in naming from a rate of 1.19 (at baseline) to 1.84 (at follow-up) on average; in contrast, control parents were stable at rates of 1.26 and .85 (at baseline and follow-up, respectively). Similarly, treatment parents increased from asking questions at a rate of 1.83 (at baseline) to 4.32 (at follow-up); control parents were stable in asking questions with rates of 1.77 and 1.90 at baseline and follow-up, respectively. Interestingly, control parents increased significantly in rate of elaborating from .35 (at baseline) to 1.17 (at follow-up), while intervention parents remained stable in this skill. There were significant differences between groups in total skill use at follow-up, F(1,21)=8.64, p=.008, and treatment parents’ increase in skills over baseline was maintained at 2 month follow-up F(1,21) = 7.73, p=.011. Groups differed in naming, linking, and asking questions at follow-up. Treatment parents maintained an increase in naming, repeating, asking questions, and rhyming and pausing over baseline rates.

Families with Different Characteristics Can Benefit From Intervention

To examine whether families with varied demographic characteristics benefitted similarly from the intervention, we examined skill gains (rate per minute) between intervention sessions in week 1 and week 6 (week 6 was chosen to reflect maximal skill use, since week 7 involved a rhyming book which limited parents ability to use the other skills). Data from participants in the waitlist control group who completed intervention training after the randomized trial portion of the study were included in this analysis. The overall sample size is smaller than 26 because multiple families missed either the week 1 or week 6 session. Applying an intent to treat approach, we describe patterns of improvement for parents with characteristics of interest who were not part of the statistical tests.

When a sufficient number of participants were represented in a category, we evaluated whether the change in skill rate was statistically significant for those participants. For demographic characteristics represented by less than 5 participants, we presented the change in rate descriptively, but did not examine whether this was a statistically significant change. The change in rates of skill use can be compared descriptively between groups to provide preliminary evidence about similarity of effects for different types of families.

Maternal Age.

To examine whether parents could gain book-sharing skills regardless of age, we compared gains demonstrated by older parents (age >32 years; n=5) to those of younger parents (<= 32 years; n=9). Age 32 represented a point in the age distribution with a gap that allowed dichotomizing into discrete groups. Younger parents increased rate of total skills significantly (p=.001), from 8.75 (SD=4.20) in week 1 to 17.55 (SD=5.01) in week 6; standardized mean difference was 3.86. Older parents also increased significantly in rate of total skills (p=.005), from 12.38 (SD=5.90) in week 1 to 18.84 (SD=5.55) in week 6; standardized mean difference was 2.55. Thus, both older and younger parents increased book-sharing skills during intervention with large effect sizes providing preliminary evidence that parent use of the skills can be increased regardless of maternal age.

Child Age.

We compared gains of parents with younger children (14–15 months; n=7) to those of parents with older children (16–18 months; n=7). Parents with younger children increased significantly in rate (p < .001) from 8.65 (SD=4.69) in week 1 to 15.89 (SD=4.55) in week 6; standardized mean difference was 2.53. Parents with older children increased in rate significantly (p < .001) from 11.90 (SD=5.14) in week 1 to 20.84 (SD=4.49) in week 6; standardized mean difference was 4.74. Thus, parents with both younger and older children demonstrated large skill gains providing preliminary evidence that parents of both younger and older children can increase in their use of these skills.

Maternal Education.

We compared gains demonstrated by parents who attended graduate school or obtained a graduate degree (n=4) to those who graduated college (n=10). Parents with graduate degrees or some graduate school increased significantly in rate (p=.017), from 11.28 (SD=6.95) in week 1 to 18.82 (SD=4.17) in week 6; standardized mean difference was 2.43. Parents with a college degree increased significantly in rate (p <.001) from 9.55 (SD=4.34) in week 1 to 17.69 (SD=5.52) in week 6; standardized mean difference was 3.30. Thus, parents of both educational backgrounds demonstrated large skill gains. One parent with less than college degree demonstrated changes in total skills from 3.6 to 16.32. A second parent with less than college increased from 20.3 to 26.37.

Child Development.

Two children had CSBS standard scores less than 85, while 12 had scores greater than 85. Parents whose children scored below 85 increased in rate, from 6.44 (SD=.54) in week 1 to 12.32 (SD=1.64) in week 6; standardized mean difference was 2.70. Parents whose children scored above 85 increased significantly in rate (t(11) = 11.42, p< .001 from 10.64 (SD=5.15) in week 1 to 18.96 (SD=4.78) in week 6; standardized mean difference was 3.30. Thus, parents of children with developmental delays increased in their skill usage by more than 2.5 standard deviations, a rate that is somewhat similar to the 3.3 standard deviation increase for parents whose development is not delayed.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to evaluate feasibility and preliminary benefits of a systematic, brief/low intensity book-sharing intervention for parents of infants and toddlers. We applied a targeted, developmentally sequenced, manualized approach to coach parent use of high-quality book-sharing strategies with children under 3 years of age. Our results support the preliminary efficacy of Ready, Set, Share A Book! as a parent-coaching intervention to support book-sharing with infants and toddlers. This study extends well-established benefits of shared reading intervention (Dowdall et al., 2020) to a younger population and replicates work of Cooper and colleagues (Vally et al., 2015; Murray et al., 2016; Cooper et al., 2014).

Notably, Ready, Set, Share A Book! was considered acceptable/usable by all parents, which provides data on feasibility of evaluating this intervention in a larger randomized controlled trial. Almost all parent-child dyads attended all eight sessions. Not only was the intervention well received, but parents felt the experience benefitted their book-sharing knowledge/confidence and ability. Accordingly, parents also observed changes in their child’s engagement (interest, enjoyment, attention, participation) during book-sharing at home. Enhancing parent capacity and child engagement are key intervention targets, because of their reciprocal relationship and importance for boosting frequency and quality of home book-sharing (Arnold and Whitehurst, 1994). Research indicates that parent knowledge and beliefs about book-sharing not only vary widely, but also directly impact parent home literacy practices (DeBaryshe, 1995; Weigel et al., 2006). Practically speaking, even modest gains in parent knowledge/confidence and/or child engagement may create key momentum for more positive book-sharing interactions and home literacy routines.

Ready, Set, Share A Book! had clear benefit for improving parents’ high quality book-sharing skills. Parents who received the intervention, compared to controls, significantly increased their overall use of high-quality book-sharing skills (48% gain in total rate from baseline) with a large effect (d=1.09). Notably, control parents did not evidence significant gains in any skills over the 4 month study period, indicating direct instruction is needed to meaningfully boost parents’ book-sharing strategies with very young children. Results of the current study suggest that while some strategies may be used more easily and naturally (e.g., lively voice), other more complex skills (e.g., linking) may require instruction and coaching to be effectively utilized with infants/toddlers. Book-sharing skills that most consistently benefitted from intervention (with medium to large effects, ranging from d=.63 to d=2.14) were naming, asking questions, linking and elaborating. These skills enhance quality of book-sharing by providing focused language stimulation and consistent opportunities for child responding (Girolametto et al., 1996). Our findings also suggest modification may be necessary to better support parent skill acquisition for strategies that demonstrated less clear or inconsistent gains, including pointing and naming, pausing to fill-in-the-blank, talking about/acting out actions and feelings. For example, using additional video examples and more focused modeling may be helpful (Huebner and Meltzoff, 2005) to evaluate in future trials. Current results also suggest that some book-sharing skills (e.g., rhyming and pausing to fill-in-the-blank) are more easily learned (or applied) by parents after a child has achieved a communication threshold for responding.

When examined intervention effects by applying a more rigorous intent to treat models, it is notable that even in this small sample size we observed significant effects for parents’ total rate of using book-sharing skills. An additional positive outcome was that parent book-sharing skills were maintained at follow-up 2 months after intervention ended (37% gain in total rate from baseline) with a large effect (d=.82). Results provide preliminary support for utility of the intervention for promoting change in key skills and is particularly significant given the relatively short duration and low intensity of intervention. Equipping parents with foundational skills may prepare them to deploy more advanced dialogic strategies to match later child gains in linguistic and cognitive ability.

The current study contributes to the literature indicating that targeting book-sharing during the period of emerging language has strong potential to optimize early language interactions (e.g., responsive, contingent, and social-emotionally attuned conversations) (Dowdall et al., 2020; Bus et al., 1995; for reviews see Scarborough and Dobrich, 1994; National Early Literacy Panel, 2008). Children in literacy-rich homes (with book-sharing occurring at least once daily) are estimated to hear a cumulative 1.4 million more words in the first 5 years, compared to children who are not read to (Logan et al., 2019); notably, this estimate only includes number of words on the page and not additional language interactions and conversations parents may have with their child during book-sharing. It is possible that the modest effects of dialogic intervention during preschool and early childhood (U.S. Department of Education IES What Works Clearinghouse, 2015) may be magnified when implemented during the critical period of emerging language development. Thus, systematic book-sharing intervention may have strong potential to shift the downstream trajectory of school readiness and early academic success for young children.

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations of the current study include the small sample size, relatively educated and low risk status, which restricts generalizability to a broader infant/toddler population. It is possible this may have restricted the gains observed for some parent book-sharing skills, or that intervention would have different acceptability/usability with a more diverse, at-risk population. Still, results provide a critical baseline for further evaluation and data were promising with respect to the potential for intervention to benefit families of different characteristics (i.e., parents of different ages and education levels and children with different language levels all demonstrated large skill gains). The reliability of our behavioral coding of parent use of book-sharing skills was within acceptable levels but still relatively low, due to the difficulty of the coding scheme as multiple parent behaviors often aligned with a single utterance. Therefore the results should be interpreted with caution.

Next steps will involve a larger randomized controlled trial with infants/toddlers of varying risk status (including those with/at-risk for language impairment), parents of varying education levels and a more diverse population of families to evaluate efficacy for parent and child outcomes. Considering potential cultural differences, along with parent values and preferences related to books (Daniels et al., 2021) and shared reading will be critical for identifying ways this manualized intervention approach may be tailored to meet the needs of diverse families.

Future research should also consider benefits of parent implemented book-sharing intervention for infant/toddler development, including language and narrative comprension. Finally, this relatively brief, low-intensity intervention is conducive to early childhood services (where providers address multiple parent goals within time-limited services), and it will be important to target delivery within early intervention systems that serve infants and toddlers, to evaluate the acceptability and efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Peter Cooper and Lynne Murray whose work was adapted for the current study and who kindly shared guidance.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Children’s Mercy Hospital Katharine Beery Richardson Grant; Kansas Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center [HD 002528]. Content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of funders.

References

- Arnold DS and Whitehurst GJ (1994) Accelerating language development through picture book reading: A summary of dialogic reading and its effects. In: Dickinson DK (ed) Bridges to literacy: Approaches to supporting child and family literacy. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, pp.103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Baxendale J and Hesketh A (2003) Comparison of the effectiveness of the Hanen Parent Programme and traditional clinic therapy. International Jounral of Language and Communication Disorders 38(4): 397–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biermiller A and Slomin N (2001) Estimating root word vocabulary growth in normative and advantaged populations: Evidence for a common sequence of vocabulary acquisition. Journal of Educational Psychology 93(3): 498–520. [Google Scholar]

- Blewitt P, Rump K, Shealy S, et al. (2009) Shared book reading: When and how questions affect young children’s word learning. Journal of Educational Psychology 101(2): 294–304. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce LK, Innocenti MS, Roggman LA, et al. (2010) Telling Stories and Making Books: Evidence for an Intervention to Help Parents in Migrant Head Start Families Support Their Children’s Language and Literacy. Early Education & Development 21(3): 343–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bus AG, van Ijzendoorn MH and Pellegrini AD (1995) Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: A meta- analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy. Review of Educational Research 65: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann A, Jooss B, Rupp A, et al. (2009) Parent based language intervention for 2-year-old children with specific expressive language delay: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Disease in Childhood 94: 110–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens LF and Kegel CAT (2021) Unique contribution of shared book reading on adult-child language interaction. J Child Lang 48(2): 373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper PJ, Vally Z, Cooper H, et al. (2014) Promoting mother–infant book sharing and infant attention and language development in an impoverished South African population: A pilot study. Early Childhood Education Journal 42(2): 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Council on Early Childhood, High PC and Klass P (2014) Literacy promotion: an essential component of primary care pediatric practice. Pediatrics 134(2): 404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels D, Salley B, Walker C, et al. (2021) Parent book choices: How do parents select books to share with infants and toddlers with language impairment? Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. DOI: 10.1177/1468798420985668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBaryshe BD (1995) Maternal belief systems: Linchpin in the home reading process. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 16(1): 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dowdall N, Melendez-Torres GJ, Murray L, et al. (2020) Shared Picture Book Reading Interventions for Child Language Development: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child Development 91(2): e383–e399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer BP, Mendelsohn AL, Kruger HA, et al. (1994) StimQ: A new scale for assessing the home environment. Reliability and validity. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 150(4): suppl 47. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis ES, Deshler DD, Lenz K, et al. (1991) An instructional model for teaching learning strategies. Focus on Exceptional Children 23(6): 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ezell HK and Justice LM (2005) Shared storybook reading: Building young children’s language and emergent literacy skills. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher KL, Perez A, Hooper C, et al. (2005) Responsiveness and attention during picture-book reading in 18-month-old to 24-month-old toddlers at risk. Early Child Development and Care 175(1): 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M, Woods J and Salisbury C (2012) Caregiver coaching strategies for early intervention providers: Moving toward operational definitions. Infants and Young Children 25: 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Girolametto L, Pearce P and Weitzman E (1996) Interactive focused stimulation for toddlers with expressive vocabulary delays. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 39(6): 1274–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave AC and Senechal M (2000) Book Reading Intervention with Preschool Children Who Have Limited Vocabularies: The Benefits of Regular Reading and Dialogic Reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 15(1): 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thieklke R, et al. (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 42(2): 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B and Risley TR (1995) Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Brookes: Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Heidlage JK, Cunningham JE, Kaiser AP, et al. (2020) The effects of parent-implemented language interventions on child linguistic outcomes: A meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 50: 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner CE and Meltzoff AN (2005) Intervention to change parent–child reading style: A comparison of instructional methods. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 26(3): 296–313. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton JS, Horowitz-Kraus T, Mendelsohn AL, et al. (2015) Home reading environment and brain activation in preschool children listening to stories. Pediatrics 136(3): 466–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser A (1993) Parent-implemented language intervention: An environmental perspective. In: Kaiser AP and Gray DB (eds) Enhancing children’s communication. Baltimore: Brookes, pp.63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser AP and Roberts MR (2013) Parent-implemented enhanced milieu teaching with preschool children who have intellectual disabilities. Journal of Speech, Langugage, Hearing Research 56: 295–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser AP and Trent JA (2007) Communication intervention for young children with disabilities: Naturalistic approaches to promoting development. In: Odom SL, Horner RH, Snell ME, et al. (eds) Handbook of Developmental Disabilities. New York, NY: Guilford Press, pp.224–245. [Google Scholar]

- Kouri TA (2005) Lexical training through modeling and elicitation procedures with late talkers who have specific language impairments and developmental delays. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 48(1): 157–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JAR, Justice LM, Yumus M, et al. (2019) When children are not read to at home: The million word gap. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 40(5): 383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin JL, Cabrera NJ and Rowe ML (2014) Low-income minority mothers’ and fathers’ reading and children’s interest: Longitudinal contributions to children’s receptive vocabulary skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 29(4): 425–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, De Pascalis L, Tomlinson M, et al. (2016) Randomized controlled trial of a book-sharing intervention in a deprived South African community: effects on carer-infant interactions, and their relation to infant cognitive and socioemotional outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 57(12): 1370–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Fiori-Cowley A, Hooper R, et al. (1996) The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother-infant interactions and later infant outcome. Child Development 67: 2512–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Early Literacy Panel (2008) Developing Early LIteracy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel. Washington, DC: National Center for Family Literacy. [Google Scholar]

- Ninio A (1983) Joint book reading as a multiple vocabulary acquisition device. Developmental Psychology 19(3): 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrelly C, Doyle O, Victory G, et al. (2018) Shared reading in infancy and later development: Evidence from an early intervention. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 54: 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MY, Kaiser AP, Wolfe C, et al. (2014) Effects of the Teach-Model-Coach-Review Instructional approach on caregiver use of language support strategies and children’s expressive language skills. Journal of Speech-Language-Hearing-Research 57: 1851–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salley B and Daniels D (2017) Ready, Set, Share A Book! An intervention program to promote language, learning and pre-literacy.

- Salley B, Daniels D, Murray L, et al. (2017) Preliminary efficacy of a book sharing intervention for caregivers and infants. In: American Speech Language Hearing Association, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough HS and Dobrich W (1994) On the efficacy of reading to preschoolers. Developmental Review 14: 245–302. [Google Scholar]

- Senechal M and Cornell EH (1993) Vocabulary acquisition through shared reading experiences. Reading Research Quarterly 28: 360–374. [Google Scholar]

- Senechal M, LeFevre J, Hudson E, et al. (1996) Knowledge of storybooks as a predictor of young children’s vocabulary. Journal of Educational Psychology 88: 520–536. [Google Scholar]

- Snow CE and Goldfield BA (1983) Turn the page please: Situation-specific language acquisition. Journal of Child Language 10(3): 551–569. [Google Scholar]

- Theriot JA, Franco SM, Sisson BA, et al. (2003) The impact of early literacy guidance on language skills of 3-year-olds. Clinical Pediatrics 42(2): 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education IES What Works Clearinghouse (2015) Early Childhood Education Intervention Report: Shared Book Reading. Reportno. Report Number|, Date. Place Published|: Institution|

- Vally Z, Murray L, Tomlinson M, et al. (2015) The impact of dialogic book-sharing training on infant language and attention: A randomized controlled trial in a deprived South African community. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 56(8): 865–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel DJ, Martin SS and Bennett KK (2006) Mothers’ literacy beliefs: Connections with the home literacy environment and pre-school children’s literacy development. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 6(2): 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby A and Prizant G (2002) Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile and Infant-Toddler Checklist (CSBS-DP). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ, Epstein JN, Angell AL, et al. (1994) Outcomes of an emergent literacy intervention in Head Start. Journal of Educational Psychology 86(4): 542. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ, Falco FL, Lonigan CJ, et al. (1988) Accelerating language development through picture book reading. Developmental Psychology 24: 552–559. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth A, Ehmig SC, Drescher N, et al. (2019) Facets of the Early Home Literacy Environment and Children’s Linguistic and Socioemotional Competencies. Early Education and Development 31(6): 892–909. [Google Scholar]

- Yont KM, Snow CE and Vernon-Feagans L (2003) The role of context in mother–child interactions: An analysis of communicative intents expressed during toy play and book reading with 12-month-olds. Journal of Pragmatics 35(3): 435–454. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.