Abstract

Cell growth in yeast colonies is a complex process, the control of which is largely unknown. Here we present scanning electron micrographs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae colonies, showing changes in the pattern of cell organization and cell-cell interactions during colony development. In young colonies (≤36 h), cell density is relatively low, and the cells seem to divide in a random orientation. However, as the colonies age, cell density increases and the cells seem to be oriented in a more orderly fashion. Unexpectedly, cells in starved colonies form connecting fibrils. A single connecting fibril 180 ± 50 nm wide is observed between any two neighboring cells, and the fibrils appear to form a global network. The results suggest a novel type of communication between cells within a colony that may contribute to the ability of the community to cope with starvation.

Evidence for cell-cell communication in bacteria has been accumulating in recent years. Numerous cases of coordinated activities of cells inside a colony have been described. It has been found that bacteria form complex communities that behave analogously to multicellular organisms (for a recent review, see reference 11). Multicellularity in bacteria regulates many aspects of bacterial physiology, such as self defense, hunting for prey, and specialization. Nevertheless, little is known about communal behavior in eukaryotic unicellular organisms.

Previously, we showed that the growth of well-separated Saccharomyces cerevisiae colonies is biphasic (3). In the first growth phase (∼24 cell divisions), most, if not all, cells divide rapidly at a rate similar to that observed in liquid medium and exhibit morphological, biochemical, and genetic characteristics of cells engaged in the cell cycle. At the end of this exponential growth, a transition to a slower growth phase is observed accompanied by a global change in the pattern of gene expression. The cells in the center of the colony then gradually enter the stationary phase, whereas the cells at the periphery continue to grow. The transition from the first to the second growth phases is sharp, suggesting that most cells synchronously respond to some environmental cues (3). This realization has led us to postulate the existence of some sort of intercellular communication, which might be manifested morphologically.

Cell organization increases with colony age.

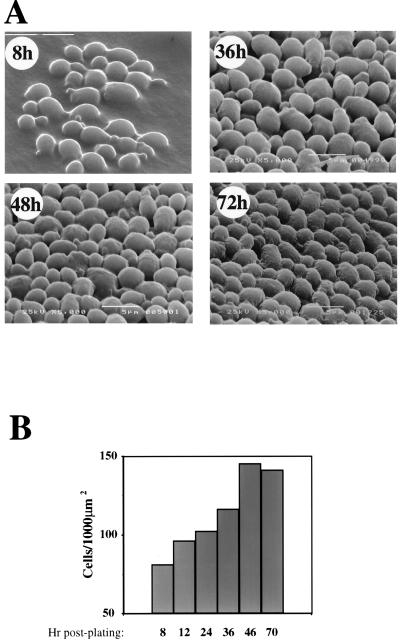

Cells in mid-logarithmic phase were plated on a solid support containing rich medium (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose [YPD]) and allowed to form colonies. Cells were allowed to undergo 4 to 5 doublings (8 h) before colonies were fixed, adapting a protocol used to fix Escherichia coli colonies (11), and inspected by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Photographs (×5,000) were taken at 45°C unless otherwise indicated. Micrographs of several colonies reveal a heterogeneous population of cells with smooth walls (Fig. 1A 8 h and results not shown). Many cells carry a bud, and some show bud scars. Micrographs of the young colonies show no discernible organization. The cells are relatively distant from each other, and the orientation of the buds with respect to the center of the colony varies from cell to cell. There is physical contact between a given cell and some of its immediate neighbors, but not with all of them.

FIG. 1.

SEM micrographs of colonies at various growth stages reveal an age-related increase in cell organization. (A) Colonies of strain SUB62 (3, 6, 7, 9, 13), grown on YPD, were fixed at the indicated time points postplating and visualized by SEM. Original magnification, ×5,000. The bar at 8 h represents 10 μm; at other time points, it represents 5 μm. (B) Top-view SEM micrographs of colonies at the indicated time points were enlarged, and the cells were counted. A total of 200 to 400 cells were counted per time point.

To determine whether cell organization changes during colony development, SEM analysis was performed at various time points after plating. Figure 1A (36 to 72 h) shows micrographs taken from the center of the colonies. Several changes in cell morphology and cell organization are observed as the colonies age. (i) Whereas the cell walls are smooth by up to 24 h, at later stages of colony development, they become wrinkled. (ii) Cells in the young colonies display little organization (e.g., Fig. 1A [8 and 36 h]); as the colonies develop, the distance between the cells and their neighbors seems to decrease, and the arrangement of the cells seems to be more ordered (Fig. 1A [72 h]). (iii) Quantitative support for the age-related increase in cell organization is provided by determining cell densities. Thus, in spite of the observation that the average cell size remains constant during the first 72 h of colony development (results not shown), the cell density on the surface of the colonies increases as the colonies age (Fig. 1B).

Level of cell organization increases from the edge to the center of a starved colony.

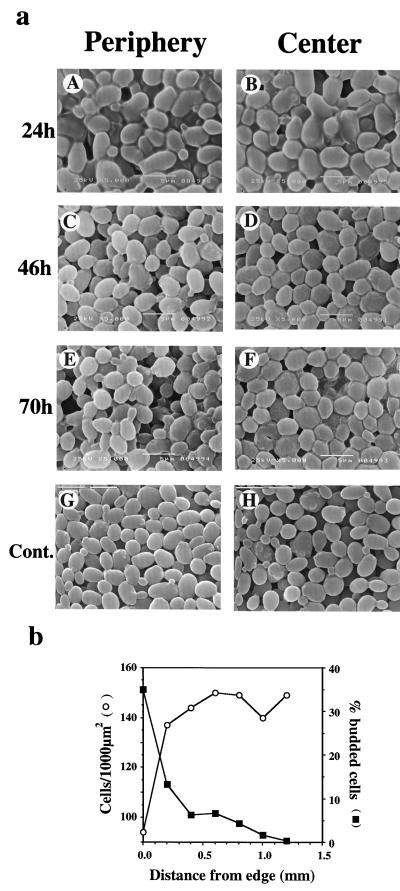

Figure 2a shows that, whereas a lack of noticeable organization is a characteristic of both the center and the periphery of young colonies (A and B), in old colonies, there is a clear difference in cell organization between the colony center and its periphery (C to F). As a control, we examined artificial colonies, which were formed by placing a packed pellet of cells on agar and immediately fixing and processing it for SEM, in exactly the same way as was done for the natural colonies. Cell organization in such “colonies” was uniform and showed no difference between the center and periphery (Fig. 2a, panels G and H), ruling out the possibility that the fixation process is affected by the location of the cells within the colony.

FIG. 2.

Cell organization depends on colony age and on the location within the colony. (a) (A to F). Top-view micrographs were taken from the colony periphery (left panels) or from the colony center (right panels). Bars represent 5 μm. (G to and H). Cells that had been grown logarithmically in liquid culture were collected, and the pellet was taken by a toothpick and placed on agar to form a colony-like structure. The artificial “colony” was immediately fixed and further processed according to the same protocol used in panels A to F. Cont., control. Micrographs of the periphery (G) and center (H) are shown. Bars represent 10 μm. (b) Top-view SEM micrographs of various locations (200 μm apart) across the radius were taken, and cell densities were determined as described for Fig. 1B and plotted as a function of the distance from the edge. In addition, cells were classified as unbudded or budded and the percent budding was similarly plotted.

In a more detailed study, in which micrographs of a 70-h-old colony were taken systematically from various locations (200 μm apart) across the colony radius, we found that cell density increases gradually from the edge to the center (Fig. 2b).

Starvation-related formation of intercellular connecting fibrils.

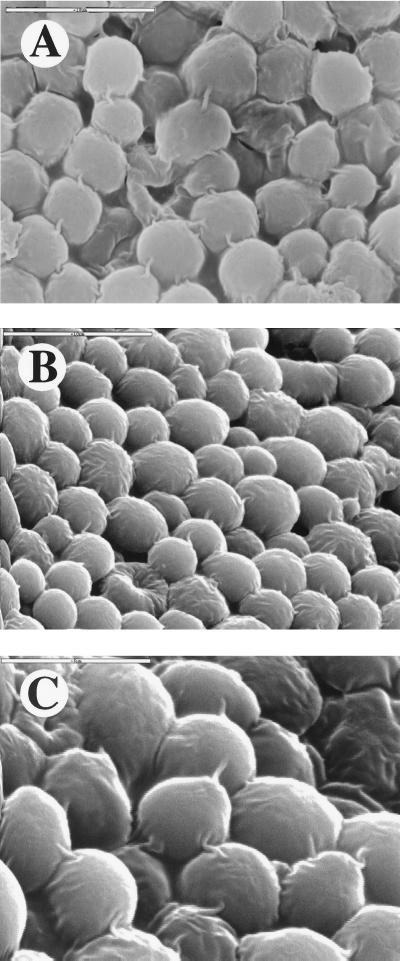

When 3-week-old colonies that had been grown on a synthetic complete (but not YPD) medium were inspected, an unexpected phenomenon was revealed: connecting fibrils that seemed to bridge neighboring cells became apparent. Because cells in old colonies are starving (3), we suspected that the appearance of the fibrils is associated with the starvation. Therefore, we challenged the colonies with more stringent starvation conditions by plating our leucine auxotroph cells on a synthetic medium with a limiting concentration of leucine. This medium could support a slow growth of tiny colonies of this strain, which appeared after a week. The colonies reached a size of ∼1 mm and could grow no further, probably because the leucine was consumed and its concentration decreased below a critical level. Under these conditions, fibrils appeared uniformly throughout the colony. They appeared in two different strain backgrounds (not shown). Since this strain is also a uracil auxotroph, cells were plated on a synthetic medium containing a limiting concentration of uracil (2 μg/ml). Again, small colonies appeared on the plate and the cells produced connecting fibrils similar to those observed in colonies starved for leucine. Thus, fibrils are produced when colonies grow on at least two different kinds of starvation media. Examples are shown in Fig. 3. Remarkably, only one fibril is detected between two neighboring cells. Thus, it seems that the number of fibrils is controlled, and their existence is likely to be biologically significant.

FIG. 3.

Intercellular connecting fibrils are found in starved colonies. Colonies were grown on plates containing synthetic medium (SD) supplemented with the standard amounts of various amino acids (14), except that the leucine concentration was limiting (1/10 that of the standard). After 3 weeks, the colonies were fixed and visualized by SEM. (A) Top view. (C) Higher magnification (originally ×10,000). Bars in panels A and B represent 10 μm, and the bar in panel C represents 5 μm.

Our work, which employs for the first time the SEM technique to investigate S. cerevisiae colonies, reveals several new features of their organization. (i) Cells in young colonies show little organization. This is different from the high degree of order found in “newborn” E. coli colonies, where communication between a daughter and a granddaughter of the colony founder cell has been found (12). (ii) As the colony develops, the average cell size remains constant, whereas cell density at the colony surface increases. These results are consistent with the observation that cells in older colonies are closer to each other and with the overall impression that the micrographs provide of increased order as the colony develops. (iii) Features characteristic of young colonies also characterize the periphery of old colonies. Note that the periphery of an old colony is the region where growth occurs and where nutrients are readily available (reference 3 and references therein). Taken together, our results demonstrate a direct correlation between the nutritional conditions that cells experience and the level of cell organization: the presence of less nutrients is correlated with a higher order of organization.

For the interpretation of the present data, it is important to consider the following observations. First, high cell density is not only a characteristic of old and large colonies, but also of tiny, yet starved, colonies that grow on leucine or uracil limiting media. Second, micrographs taken from various locations across these tiny and starved colonies show similar organization and similar cell density (results not shown). Third, we have created an artificial colony and found no difference in cell density or organization at various locations of the “colony” (see Fig. 2). Taken together, our results led us to propose that a high level of organization is a feature of starvation experienced by the colonies prior to fixation and is not a consequence of several parameters that could artifactually affect the results, such as colony size or the actual location within the colony.

The mechanism responsible for the increased organization in starved colonies is unknown. Because there is no evidence for cell motility in S. cerevisiae, it is hard to conceive how cells in the colony can be rearranged. Therefore, it is likely that a higher level of organization is achieved by some coordination of cell division. According to this possibility, the organization must be initiated before the cells enter the stationary phase, probably when they start to sense starvation. Indeed, cell density increases gradually during development, beginning before the cells enter the stationary phase (Fig. 1B).

What adaptive advantages do yeast derive from the high degree of cell organization? At present, the answer to this question can only be speculative and teleological. When a single cell is plated on a solid and rich medium, it encounters optimal conditions for growth. It then divides at its maximal capacity and starts to form a colony. As long as nutrients are not present at limiting concentrations and there is no accumulation of toxic metabolites, the cells divide independently of each other and no coordination or communication is necessary for optimal proliferation. Hence, during this phase of colony growth, no order is required. We hypothesize that order is a burden on the individual cell because it requires energy-consuming communication. Thus, order is established only when it provides a significant biological advantage. As the colony develops, nutrients become less available to cells that are distant from the nutritious agar (3). We speculate that order is established to cope with the starvation itself, as well as with other stresses, such as dehydration, that are usually associated with long-term starvation periods. Moreover, order may also facilitate a passive capillary movement of nutrients from the agar to the top cell layers through the pores in the cell walls (see Discussion in reference 3). Another parameter that might affect organization of colony cells is the accumulation of metabolic by-products or other molecules (pheromone-like) secreted by the cells. Two well-known examples of by-products are (i) ethanol, a product of fermentation, and (ii) ammonia, a product of amino acid metabolism. Indeed, ammonia is involved in long distance communication between colonies (4). However, whether or not ammonia or other secreted materials play a role in cell-cell communication within a single colony remains to be determined.

Organization of old yeast colonies is more complex than is evident from the SEM micrographs. Inspection of lacZ-containing colonies, grown on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (X-Gal)-containing agar, revealed a complex pattern of staining in which clonal minisectors are detected. When sublethal concentrations of OsO4 were used for fixation, a differential staining of the colony cells was observed, which led to the appearance of concentric rings of dark and light stains (results not shown), similar to the patterns observed in E. coli (10, 11). However, our SEM analyses failed to detect sectors or concentric rings. It is likely that in S. cerevisiae, the differential staining is based on biochemical differences between cells rather than differences in cell organization within the colony.

In addition to the increase in the overall organization during colony development, suggesting some sort of communication between cells, we observed a possible new type of communication mediated by connecting fibrils. Under our experimental conditions, a single fibril connected two neighboring cells. This observation favors the possibility that fibril number is controlled. Their limited number suggests that they play a regulatory role rather than simply a mechanical function. The function of the fibrils remains to be determined. Two alternative, but not mutually exclusive, functions can be envisaged. (i) Fibrils may play a role in signal sensing and transduction. The signals are likely to be transmitted from one cell to its immediate neighbors. However, theoretically, the fibrils can transmit the signal from one location in the colony to a far distant location, because the fibrils and the cell walls seem to form a continuous network that connects all the cells. (ii) Fibrils serve as connecting channels for the transport of molecules from one cell to the other. Their diameter, 180 ± 50 nm, is theoretically large enough to permit the passage of macromolecules. By way of comparison, the outer diameter of the nuclear pore complex in yeast (which includes the building proteins), which serves as the only channel for nucleocytoplasmic traffic, is 100 nm (15).

Cell-cell interaction and colony organization have been observed in a number of unicellular organisms. The most thoroughly investigated examples are Dictyostelium discoideum and myxobacteria. In both organisms, organization is by far more complex than that observed in S. cerevisiae, ending in the formation of a quasidifferentiated organ, the fruiting body (1, 5). Development of the fruiting body is induced by starvation and involves cell-cell interaction. In myxobacteria, this interaction is apparently mediated by fibrils 30 nm wide, which are composed of polysaccharides and proteins (1). Extracellular appendages have also been found in other prokaryotic organisms, where they usually serve for attachment to some matrix. For example, a role in the internalization into epithelial cells has been attributed to surface appendages of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (2). Fibrilar structures have also been found in the yeast Candida albicans (8, 16). The published SEM micrographs show an irregular appearance of the fibrils. It is not clear whether these fibrils are present constitutively or are synthesized in response to some environmental cues. Nevertheless, they were found in mature colonies of the O smooth morphology (8), but there is no documentation of their presence in C. albicans colonies of other morphologies.

The fibrils found in S. cerevisiae differ from those observed in bacteria. First, only a single fibril was found between two neighboring S. cerevisiae cells, whereas in bacteria, the number is much greater (1, 2). Second, the diameter of the S. cerevisiae fibrils is significantly larger than those found in bacteria. These differences imply that the S. cerevisiae fibrils fulfill a novel function.

The picture that emerges from many studies is that colonies can be regarded as well-organized multicellular organisms rather than lines of cells that coexist in close proximity (11). According to the present study, this notion also holds true for S. cerevisiae colonies, whose level of organization has not been appreciated in the past. One distinction that can be made between unicellular organisms and “true” multicellular organisms is that organization of the former is not an obligatory feature of the cell community under all conditions, but rather an induced feature occurring in response to environmental signals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Naomi Bahat for excellent technical assistance in taking the SEM photomicrographs and James A. Shapiro for valuable advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dworkin M. Fibrils as extracellular appendages of bacteria: their role in contact-mediated cell-cell interactions in Myxococcus xanthus. Bioessays. 1999;21:590–595. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199907)21:7<590::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginocchio C C, Olmsted S B, Wells C L, Galan J E. Contact with epithelial cells induces the formation of surface appendages on Salmonella typhimurium. Cell. 1994;76:717–724. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meunier J-R, Choder M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae colony growth and aging: biphasic growth accompanied by changes in gene expression. Yeast. 1999;15:1159–1169. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19990915)15:12<1159::AID-YEA441>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palkova Z, Janderova B, Gabriel J, Zikanova B, Pospisek M, Forstova J. Ammonia mediates communication between yeast colonies. Nature. 1997;390:532–536. doi: 10.1038/37398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parent C A, Devreotes P N. Molecular genetics of signal transduction in Dictyostelium. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:411–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paz I, Abramovitz L, Choder M. Starved saccharomyces cerevisiae cells have the capacity to support internal initiation of translation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21741–21745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paz I, Meunier J R, Choder M. Monitoring dynamics of gene expression in yeast during stationary phase. Gene. 1999;236:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radford D R, Challacombe S J, Walter J D. A scanning electronmicroscopy investigation of the structure of colonies of different morphologies produced by phenotypic switching of Candida albicans. J Med Microbiol. 1994;40:416–423. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-6-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenheck S, Choder M. Rpb4, a subunit of RNA polymerase II, enables the enzyme to transcribe at temperature extremes in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6187–6192. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6187-6192.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro J A. The significances of bacterial colony patterns. Bioessays. 1995;17:597–607. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro J A. Thinking about bacterial populations as multicellular organisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:81–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro J A, Hsu C. Escherichia coli K-12 cell-cell interactions seen by time-lapse video. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5963–5974. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5963-5974.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheffer A, Varon M, Choder M. Rpb7 can interact with RNA polymerase II and support transcription during some stresses independently of Rpb4. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2672–2680. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherman F, Fink G R, Hicks J B. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoffler D, Fahrenkrog B, Aebi U. The nuclear pore complex: from molecular architecture to functional dynamics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:391–401. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whittaker D K, Drucker D B. Scanning electron microscopy of intact colonies of microorganisms. J Bacteriol. 1970;104:902–909. doi: 10.1128/jb.104.2.902-909.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]