Abstract

The Mycobacterium smegmatis pncA gene, encoding nicotinamidase/pyrazinamidase, was identified. While it was similar to counterparts from other mycobacteria, the M. smegmatis PncA had little homology to the other M. smegmatis pyrazinamidase/nicotinamidase, encoded by the pzaA gene. Transformation of Mycobacterium bovis strain BCG with M. smegmatis pncA or pzaA conferred susceptibility to pyrazinamide.

Pyrazinamide (PZA), an important frontline tuberculosis drug, is a structural analog of nicotinamide. Nicotinamide and PZA are converted to nicotinic acid and pyrazinoic acid (POA), respectively, by the same enzyme, nicotinamidase/pyrazinamidase (PZase) (6, 13), although the enzyme converts the latter less efficiently, at least in the case of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (18). PZA is a prodrug that must be converted to the active form POA by the bacterial PZase in order to inhibit M. tuberculosis (6, 13). Loss of this enzyme activity is closely associated with development of PZA resistance in M. tuberculosis (6, 9, 11, 20). We have identified the nicotinamidase/PZase gene pncA, encoding a 20-kDa protein (13), and have shown that mutation in pncA is the major mechanism of PZA resistance in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis (2, 15, 16). This finding has been confirmed by other studies (5, 7, 8, 10).

To identify the PZase that is involved in PZA susceptibility, Boshoff and Mizrahi identified a PZase/nicotinamidase gene, pzaA, from naturally PZA resistant Mycobacterium smegmatis (1). The pzaA gene encodes a 50-kDa protein that does not have significant homology to the 20-kDa mycobacterial PncA proteins. Overexpression of PzaA on a multicopy plasmid conferred increased susceptibility to PZA in M. smegmatis. However, mutant strains of M. smegmatis with inactivated pzaA genes still had residual PZase activity (1), indicating the presence of some other PZase enzyme(s) in this organism. To account for the additional PZase activity in M. smegmatis, in this study, we identified the pncA gene, encoding a second nicotinamidase/PZase in M. smegmatis.

Identification of two PZase activities in M. smegmatis.

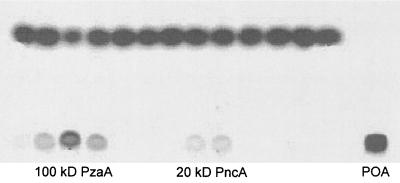

Protein extracts from M. smegmatis strain mc26 (kindly provided by Bill Jacobs) were prepared as described elsewhere (23). Soluble protein extracts were loaded on a Bio-Gel P100 (Bio-Rad) size exclusion column, which was washed with 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 1 mM EDTA. Various fractions were collected and assayed for PZase activity as described elsewhere (18). Molecular masses of enzymes were determined according to a standard curve established with known molecular weight markers (Bio-Rad). Two distinct PZase activities with molecular masses of 20 and 100 kDa in M. smegmatis were identified (Fig. 1). The 100-kDa PZase activity was about five- to sixfold higher than the 20-kDa enzyme activity in the soluble extracts as assessed by densitometry of autoradiography. The 100-kDa activity is most likely a dimer form of the PzaA enzyme with a monomer molecular mass of 50 kDa (1). Protein sequencing of the 20-kDa activity was unsuccessful. The 20-kDa PZase activity cross-reacted with a polyclonal antiserum raised against the M. tuberculosis PncA protein (data not shown). The cross-reactivity with the antiserum against M. tuberculosis PncA and the concordant molecular mass suggest that the 20-kDa activity is the PncA enzyme of M. smegmatis. However, the 20-kDa PZase activity was not identified in a previous study (1), probably because a 30-kDa cutoff was used in the purification scheme such that the 20-kDa PncA of M. smegmatis (see below) was missed.

FIG. 1.

Two PZase activities in M. smegmatis. Various fractions from the Bio-Gel P100 column were tested for PZase activity using [14C]PZA followed by thin-layer chromatography and autoradiography as described elsewhere (18). Two distinct PZase activities were identified in M. smegmatis extracts.

Cloning and sequence analysis of the M. smegmatis pncA gene.

To identify the M. smegmatis pncA gene, we amplified a partial pncA DNA fragment (about 394 bp) by PCR from M. smegmatis strain mc26 genomic DNA, using degenerate primers. The forward primer (5′CARAAYGAYTTYTGYGARGG3′) was designed according to conserved amino acid sequence QNDFCEG at positions 10 to 16 of the mycobacterial PncA proteins (18). The reverse primer (5′GCCGACSACRTCSACMTCGTC3′) was designed according to conserved amino acid sequence DEVDVVG at positions 126 to 132. PCR was performed as described elsewhere (12); conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. Sequence analysis indicated that the PCR product had a high degree of homology to the known mycobacterial PncA proteins (data not shown). The M. smegmatis pncA PCR product was used as a probe to screen an M. smegmatis λZAPII phage DNA library to obtain the complete pncA gene. A positive clone with a 2.6-kb DNA insert containing the M. smegmatis pncA gene was identified. The 2.6-kb insert was obtained by PCR using T7 and T3 primers complementary to the λZAPII vector and was subcloned into the pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen) for DNA sequencing.

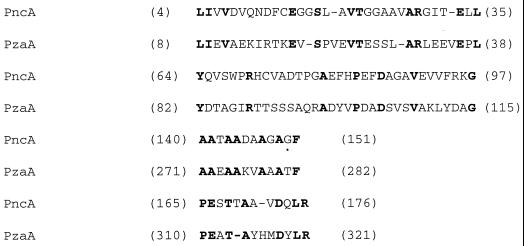

Sequence analysis indicated that the M. smegmatis pncA gene encoded a protein of 187 amino acids with a predicted mass of 19,785.91 Da. The M. smegmatis PncA had 75, 71, 69, and 33% amino acid identities to its counterparts from M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium avium, and Escherichia coli, respectively. It is interesting that while M. smegmatis PncA and PzaA both have PZase and nicotinamidase activities, they share little homology. The overall amino acid identity between the two proteins is 16.2%. A Block Maker homology search (Baylor College of Medicine search launcher) identified four regions of homology between M. smegmatis PncA and PzaA protein sequences (Fig. 2), which may be the basis for the PZase and nicotinamidase activities of both enzymes. Comparative crystallography studies are needed to understand the common mechanistic feature of the two enzymes.

FIG. 2.

Regions of conservation between M. smegmatis PncA and PzaA. Block Maker analysis of M. smegmatis PncA and PzaA shows the conserved amino acid residues in the two enzymes.

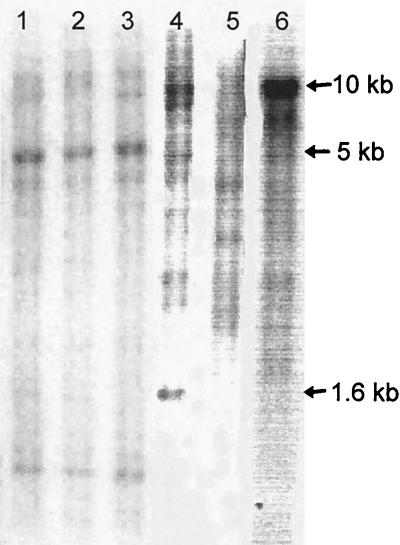

Presence of pncA homologs in mycobacteria.

Mycobacterial genomic DNA was digested with BamHI and subjected to Southern blot analysis as described elsewhere (21). The DNA probe used was the 394-bp M. smegmatis pncA PCR product labeled with [32P]dCTP. After hybridization, the blot was washed under low stringency. The M. smegmatis pncA probe hybridized with a 1.6-kb BamHI fragment from M. avium (ATCC 25291) (Fig. 3, lane 4). In a previous study (17), hybridization of M. tuberculosis pncA with genomic DNA from M. smegmatis was not detected, presumably because the hybridization condition was too stringent for detection of any hybridization signal. However, with very low stringency washing at room temperature, the M. smegmatis pncA probe hybridized faintly with a 5-kb fragment from Mycobacterium bovix BCG-Pasteur and M. tuberculosis strains H37Ra and H37Rv (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 3). The M. smegmatis pncA probe hybridized strongly with a fragment of more than 10 kb (lane 6) with M. smegmatis itself but failed to hybridize to genomic DNA from M. kansasii (ATCC 12478) (lane 5).

FIG. 3.

Southern blot analysis of pncA homologs in mycobacteria using an M. smegmatis pncA probe. Lanes: 1, M. bovis BCG-Pasteur; 2, M. tuberculosis H37Ra; 3, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; 4, M. avium; 5, M. kansasii; 6, M. smegmatis.

Transformation of BCG with M. smegmatis pncA or pzaA produced functional PZase and nicotinamidase activities and restored PZA susceptibility.

The pncA and pzaA plasmid constructs for transformation of M. bovis BCG were made as follows. The PCR forward primer (5′GGAGGTACCTCTACGCGCAGACGTGATGCTCGC3′) was from −248 to −221 bp upstream of M. smegmatis pncA. The reverse primer (5′GCTGGTACCGGTGTTGCAATCATCACCCG3′) was from 16 bp downstream of the M. smegmatis pncA stop codon. These pncA primers produced a PCR product of 839 bp. The 1,688-bp DNA fragment containing the M. smegmatis pzaA gene (GenBank accession no. AF058285) and its promoter was amplified by PCR using a forward primer (5′GAGGGTACCAGCGAGGAGACCCATGTCCG3′) from 145 bp upstream of the pzaA start codon and a reverse primer (5′CCGGGTACCCAGGCCGGTGCCGAGCGCCA3′) from 25 bp downstream of the pzaA stop codon. KpnI sites (underlined) were incorporated into the PCR primers. The 839- or 1,688-bp PCR fragment containing M. smegmatis pncA or pzaA, respectively, was cloned into the KpnI site of the hygromycin mycobacterial shuttle vector p16R1 (4). The p16R1-M. smegmatis pncA and pzaA constructs and the same vector harboring the M. tuberculosis pncA gene on a 3.2-kb DNA fragment (13, 17), along with the vector control, were transformed into naturally PZA resistant M. bovis BCG-Pasteur as described elsewhere (22).

BCG is known to be a natural mutant of PncA with no apparent PZase activity due to a single change of C to G at nucleotide 169 causing an amino acid change of His in the M. tuberculosis enzyme to Asp in the M. bovis BCG enzyme (13, 14). This feature allowed us to examine the relative PZase and nicotinamidase activities of M. smegmatis PncA and PzaA, using BCG. The BCG vector control had negligible PZase or nicotinamidase activity. The M. smegmatis pncA and pzaA constructs produced 5.7- and 4.3-fold higher, respectively, nicotinamidase activity than PZase activity in BCG. While the pzaA construct produced somewhat less nicotinamidase activity than the M. smegmatis pncA construct, it produced more PZase activity in BCG (Table 1). However, the difference in PZase activity of the pzaA and pncA constructs in BCG (less than twofold) is less than that for the two enzymes in the M. smegmatis protein extract (about five- to sixfold) (Fig. 1). This difference is most likely due to different promoter activities of the two constructs in BCG versus M. smegmatis. On the other hand, while the M. tuberculosis pncA construct exhibited nicotinamidase activity similar to that of the M. smegmatis pncA or pzaA construct, it produced over 10-fold less PZase activity than the M. smegmatis pncA or pzaA construct (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities to PZA and PZase and nicotinamidase activities of BCG transformantsa

| BCG transformant | PZA MIC (μg/ml) | Mean activity (U/mg of protein) ± SD

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| PZase | Nicotinamidase | ||

| M. smegmatis pncA | 3.1 | 1,432 ± 271 | 8,065 ± 29 |

| M. smegmatis pzaA | 25 | 1,775 ± 205 | 7,549 ± 676 |

| M. tuberculosis pncA | 50 | 119 ± 6 | 9,920 ± 962 |

| Vector control | >500 | 12 ± 2 | 35 ± 9 |

| M. tuberculosis H37Ra | <50 | 64 ± 8 | 1,359 ± 50 |

| M. smegmatis mc26 | >2,000 | 360 ± 20 | 1,173 ± 150 |

Cell extracts were prepared as described elsewhere (23). Relative PZase and nicotinamidase activities were assayed using [14C]PZA (52 mCi/mmol) and [14C]nicotinamide (45.4 mCi/mmol) as described previously (18). One unit of PZase or nicotinamidase is defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 nM POA or nicotinic acid in 1 h at 37°C (19).

Transformation of BCG with M. smegmatis pncA or pzaA conferred susceptibility to PZA (Table 1). The susceptibility to PZA was determined on 7H11 agar plates (pH 5.5) containing 3.1, 6.2, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, or 500 μg of PZA per ml as described elsewhere (18). It is interesting that BCG transformed with the M. smegmatis pncA construct became highly susceptible to PZA, with an MIC of 3.1 μg/ml, whereas BCG transformed with the pzaA construct was susceptible to 25 μg of PZA per ml. However, the degree of susceptibility to PZA for the two constructs did not correlate with the amount of PZase activity expressed in BCG (Table 1). It is possible that the liquid-grown cultures used for measurement of PZase activity had bacterial populations that did not overexpress PZase activity, which could result in a difference in the amount of PZase from the plate-grown bacteria for determining the MIC. Alternatively, this may reflect different effects of overexpression of PzaA versus PncA on the viability of the organism in addition to the ability to convert PZA to POA.

In this study, we found that M. smegmatis has a second PZase activity of 20 kDa encoded by the pncA gene in addition to the 50-kDa PZase encoded by the pzaA gene (1). Despite ample PZase activities, M. smegmatis is highly resistant to PZA. We have shown that this natural PZA resistance of M. smegmatis relates to its highly active efflux mechanism for POA (23). In contrast, the susceptible M. tuberculosis has only a single PZase enzyme encoded by the pncA gene. Despite the presence of several PzaA homologs (AmiD, AmiC, AmiB2, and GatA) in M. tuberculosis (3), they apparently do not have PZase activity and are not involved in PZA action since PZA-resistant M. tuberculosis strains with pncA mutations lack PZase (6, 9, 11, 20). Mutations of pncA render M. tuberculosis deficient in PZase activity and lead to acquired PZA resistance because of impaired ability of the enzyme to convert PZA to active POA. The unique susceptibility of M. tuberculosis to PZA correlates with its defective POA efflux mechanism (23). While overexpressing PzaA on a multicopy plasmid in M. smegmatis could cause increased susceptibility in this organism (MIC from over 2,000 to 150 μg of PZA per ml) (1), we have shown here that similarly overexpressing PzaA or PncA conferred much higher PZA susceptibility in the POA efflux-deficient M. tuberculosis complex organism BCG (MICs of 25 and 3.1 μg/ml).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The M. smegmatis pncA sequence has been assigned GenBank accession no. AF117900.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants (AI40584 and AI44063) and the Potts Memorial Foundation.

We acknowledge receipt of the λZAPII M. smegmatis genomic DNA library and [14C]PZA from the NIH AIDS Reagents Program (Rockville, Md.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Boshoff H I M, Mizrahi V. Purification, gene cloning, targeted knockout, overexpression, and biochemical characterization of the major pyrazinamidase from Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5809–5814. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5809-5814.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng S J, Thibert L, Sanchez T, Heifets L, Zhang Y. pncA mutations as a major mechanism of pyrazinamide resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: spread of a monoresistant strain in Quebec, Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:528–532. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.3.528-532.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garbe T, Barathi J, Barnini S, Zhang Y, Abou-Zeid C, Tang D, Mukherjee R, Young D. Transformation of mycobacterial species using hygromycin resistance as selectable marker. Microbiology. 1994;140:133–138. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirano K, Takahashi M, Kazumi Y, Fukasawa Y, Abe C. Mutation in pncA is a major mechanism of pyrazinamide resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997;78:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(98)80004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konno K, Feldman F M, McDermott W. Pyrazinamide susceptibility and amidase activity of tubercle bacilli. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967;95:461–469. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.95.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemaitre N, Sougakoff W, Truffot-Pernot C, Jarlier V. Characterization of new mutations in pyrazinamide-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and identification of conserved regions important for the catalytic activity of the pyrazinamidase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1761–1763. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marttila H J, Marjamaki M, Vyshnevskaya E, Vishnevskiy B I, Otten T F, Vasilyef A V, Viljanen M K. pncA mutations in pyrazinamide-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from northwest Russia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1764–1766. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClatchy J K, Tsang A Y, Cernich M S. Use of pyrazinamidase activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a rapid method for determination of pyrazinamide susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;20:556–557. doi: 10.1128/aac.20.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mestdagh M, Fonteyne P A, Realini L, Rossau R, Jannes G, Mijs W, De Smet K A L, Portaels F, Van Den Eeckhout E. Relationship between pyrazinamide resistance, loss of pyrazinamidase activity, and mutations in the pncA locus in multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2317–2319. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller M, Thibert L, Desjardins F, Siddiqi S, Dascal A. Testing of susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide: comparison of Bactec method with pyrazinamidase assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2468–2470. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2468-2470.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scorpio A, Zhang Y. Mutations in pncA, a gene encoding pyrazinamidase/nicotinamidase, cause resistance to the antituberculous drug pyrazinamide in tubercle bacillus. Nat Med. 1996;2:662–667. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scorpio A, Collins D, Whipple D, Cave D, Bates J, Zhang Y. Rapid differentiation of bovine and human tubercle bacilli based on a characteristic mutation in the bovine pyrazinamidase gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;32:106–110. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.106-110.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scorpio A, Lindholm-Levy P, Heifets L, Gilman R, Siddiqi S, Cynamon M H, Zhang Y. Characterization of pncA mutations in pyrazinamide-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:540–543. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sreevatsan S, Pan X, Zhang Y, Kreiswirth B, Musser J M. Mutations associated with pyrazinamide resistance in pncA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:636–640. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Z H, Scorpio A, Zhang Y. The pncA gene from the naturally pyrazinamide-resistant Mycobacterium avium encodes pyrazinamidase and confers pyrazinamide susceptibility to resistant M. tuberculosis complex organisms. Microbiology. 1997;143:3367–3373. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-10-3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Z H, Zhang Y. Reduced pyrazinamidase and the natural resistance of Mycobacterium kansasii to the antituberculosis drug pyrazinamide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:537–542. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanigawa Y, Shimoyama M, Ueda I. Nicotinamide deamidase from Flavobacterium peregrinum. Methods Enzymol. 1980;66:132–136. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(80)66450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trivedi S S, Desai S G. Pyrazinamidase activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis—a test of sensitivity to pyrazinamide. Tubercle. 1987;68:221–224. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(87)90058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Garcia M J, Lathigra R, Allen B, Moreno C, van Embden J D A, Young D. Alterations in the superoxide dismutase gene of an isoniazid-resistant strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2160–2165. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2160-2165.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Garbe T, Young D. Transformation with katG restores isoniazid sensitivity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates resistant to a range of drug concentrations. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:521–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Scorpio A, Nikaido H, Sun Z. Role of acid pH and deficient efflux of pyrazinoic acid in the unique susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2044–2049. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2044-2049.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]