Abstract

The GacS-GacA two-component signal transduction system, which is highly conserved in gram-negative bacteria, is required for the production of exoenzymes and secondary metabolites in Pseudomonas spp. Screening of a Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 gene bank led to the isolation of a previously undefined locus which could restore secondary metabolite production to both gacS and gacA mutants of F113. Sequence analysis of this locus demonstrated that it did not contain any obvious Pseudomonas protein-coding open reading frames or homologues within available databases. Northern analysis indicated that the locus encodes an RNA (PrrB RNA) which is able to phenotypically complement gacS and gacA mutants and is itself regulated by the GacS-GacA two-component signal transduction system. Primer extension analysis of the 132-base transcript identified the transcription start site located downstream of a ς70 promoter sequence from positions −10 to −35. Inactivation of the prrB gene in F113 resulted in a significant reduction of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (Phl) and hydrogen cyanide (HCN) production, while increased metabolite production was observed when prrB was overexpressed. The prrB gene sequence contains a number of imperfect repeats of the consensus sequence 5′-AGGA-3′, and sequence analysis predicted a complex secondary structure featuring multiple putative stem-loops with the consensus sequences predominantly positioned at the single-stranded regions at the ends of the stem-loops. This structure is similar to the CsrB and RsmB regulatory RNAs in Escherichia coli and Erwinia carotovora, respectively. Results suggest that a regulatory RNA molecule is involved in GacA-GacS-mediated regulation of Phl and HCN production in P. fluorescens F113.

Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 was isolated as a biocontrol agent for the control of Pythium ultimum-mediated damping-off of sugar beet (35). Inhibition of Pythium ultimum has been attributed to the production of the antimicrobial agent 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (Phl) (11). However, the strain also synthesizes hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and an exoprotease. These secondary metabolites and exoprotease have previously been shown to be positively regulated by the GacS (previously LemA) and GacA two-component signal transduction system (8) common to numerous Pseudomonas spp., including P. syringae (31), P. viridiflava (18), P. aeruginosa (30), and P. fluorescens (6, 13, 17, 32). Sensor proteins such as GacS are typically transmembrane proteins that respond to environmental stimuli by autophosphorylation, followed by transfer of the phosphate to the cognate response regulator, in this case GacA. The GacA response regulator contains a DNA binding motif and is thought to activate or repress genes directly by binding to the target gene promoter. However, direct binding of GacA to putative target promoters has yet to be demonstrated.

Recent research in P. aeruginosa PAO (30) has revealed that the GacS-GacA signal transduction system contributes to a larger regulatory cascade involving acyl-homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing and alternate sigma factors. Indeed, Reimmann et al. (30) demonstrated that GacA positively controls the production of N-butyryl-homoserine lactone. Furthermore, N-butyryl-homoserine lactone was demonstrated to regulate virulence factors, such as pyocyanin, cyanide, and lipase, and to activate the transcription of rpoS, which encodes the post-exponential phase and stress response sigma factor ςS. The potential for additional factors to be involved in GacS regulation was demonstrated by Kitten and Willis (15). This research revealed that overexpression of the ribosomal proteins L35 and L20 could partially complement the gacS (lemA) mutant phenotype of P. syringae.

P. fluorescens F113 gacS mutants and gacA mutants do not synthesize Phl, HCN, or exoprotease (8). These phenotypes are restored upon complementation in trans with the respective genes. However, the direct activation of the genes responsible for these phenotypes through GacA binding has yet to be demonstrated. Indeed, activation of secondary metabolites and exoenzymes in P. fluorescens F113 may involve a more complex regulatory cascade, and evidence for this is presented here with the description of the prrB gene encoding a regulatory RNA molecule.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. fluorescens F113 and derivatives were routinely grown at 28°C in sucrose asparagine medium (34). The medium was supplemented, where indicated, with 100 μM FeCl3 for high-iron conditions. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or agar. Antibiotics when required, were added to the medium at the following concentrations: for tetracycline, 25 μg ml−1 for E. coli and 75 μg ml−1 for P. fluorescens; for chloramphenicol, 30 μg ml−1 for E. coli and 200 μg ml−1 for P. fluorescens; and for kanamycin, 25 μg ml−1 for E. coli and 50 μg ml−1 for P. fluorescens.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | ||

| F113 | Wild type, Phl+ HCN+ Prt+lac | 35 |

| FG9 | F113 gacAΩ::mini-Tn5-lac Phl− HCN− Prt−lac Kmr | 8 |

| FL33 | F113 gacSΩ::mini-Tn5-lac Phl− HCN− Prt−lac Kmr | 8 |

| FRB1 | F113 prrB::Ω-Tc, Phl+ HCN+ Prt+lac Tcr | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5-α | φ80 lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 thi-1 | 33 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBR1MCS | Cloning vector, BHR, Cmr | 16 |

| pSUP106 | Cloning vector, BHR, Tcr | 36 |

| pK18 | Cloning vector, NHR, ColE1, Kmr | 28 |

| pMP220 | Promoterless lacZ vector, IncP, Tcr | 37 |

| pRK2013 | Helper plasmid, Tra+ Mob+ ColE1 Kmr | 12 |

| pHP45-Tc | ColE1 replicon carrying an Ω-Tc; Apr Tcr | 27 |

| pCU300 | pSUP106 carrying a 5.4-kb BamHI fragment from P. fluorescens F113; Cmr | This study |

| pCU301 | pBBR1MCS carrying a 2.8-kb BamHI-HindIII fragment from pCU300; Cmr | This study |

| pCU302 | pBBR1MCS carrying a 3.3-kb BamHI-SalI fragment from pCU300; Cmr | This study |

| pCU303 | pBBR1MCS carrying a 2.1-kb BamHI-SalI fragment from pCU300; Cmr | This study |

| pCU304 | pBBR1MCS carrying a 0.85-kb HindIII-EcoRV fragment amplified from pCU301; Cmr | This study |

| pCU305 | pBBR1MCS carrying a 228-bp KpnI-BamHI fragment amplified from pCU301; Cmr | This study |

| pCU306 | pK18 carrying a 5-kb BamHI-XhoI fragment from pCU300 with Ω-Tc cassette inserted into prrB; Kmr Tcr | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Kmr, kanamycin resistant, Tcr, tetracycline resistant.

Construction of pCU300 derivatives.

The P. fluorescens F113 genomic DNA fragment was subcloned from pCU300 as a BamHI-HindIII fragment into the broad-host-range (BHR) vector pBBR1MCS to form pCU301. SalI-BamHI fragments from pCU300 were subcloned into pBBR1MCS to form pCU302 and pCU303. The M13/pUC reverse primer (P1) (5′-AGCGGATAACAATTTCACAGGA-3′) and primer P2 (5′-CTGATATCCCCTGCGTTCGT-3′), which incorporates a EcoRV site, were used to amplify the locus that was cloned in pBBR1MCS to form pCU304. A 228-bp fragment containing the putative prrB gene was amplified by PCR using the primers P3 (5′-CGTAGCGGTACCGAGCAAGCCA-3′), which carries a KpnI site, and P4 (5′-TTCGGATCCAGAAATCGCAGGC-3′), which carries a BamHI site, and cloned into the KpnI-BamHI sites of pBBR1MCS to form pCU305.

Construction of F113prrB mutant.

The BamHI-XhoI fragment of pCU300 was subcloned into the BamHI-SalI sites of the narrow-host-range (NHR) vector pK18 (28). The Ω-Tc fragment was isolated as a SmaI fragment from plasmid pHP45-Tc (27) and blunt end ligated into the SalI site (33) within prrB. The resulting pCU306 suicide construct was introduced into F113 by electroporation, and double-crossover transformants were selected as Tcr and Kms. The resulting prrB mutant (FRB1) in which the Ω-Tc fragment had inserted within the chromosomal prrB copy was verified by Southern and Northern blot hybridization.

Exoproduct assays.

Phl synthesis was assessed qualitatively using the Bacillus inhibition plate bioassay described previously (11). Pseudomonas test strains were assayed for Phl production by high-performance liquid chromatography as previously described (35). Proteolytic activity was assayed qualitatively using skim milk agar plates (9). Briefly, strains were streaked onto the plates and incubated for 72 h at 30°C, and then the diameters of the clearing zones were compared. Hydrogen cyanide production was detected qualitatively using the filter paper assay described previously (3). Quantification of hydrogen cyanide was performed as described previously (38).

DNA manipulations and cloning procedures.

Small- and large-scale plasmid DNA isolation was performed using Qiagen Plasmid Mini and Maxi kits, respectively, according to the manufacturer's specifications (Qiagen). Restriction digestion and ligation procedures were performed by the methods of Sambrook et al. (33). Chromosomal DNA was isolated by the method of Chen and Kuo (5). Following electrophoretic separation, DNA fragments were purified from gels using the QiaexII gel extraction kit according to the manufacturer's specifications (Qiagen). Plasmids were introduced into E. coli and Pseudomonas by electroporation (10) or mobilized into Pseudomonas by triparental matings using helper plasmid pRK2013 (12). Southern blotting was performed by capillary transfer of genomic DNA from 0.8% agarose gels onto a nylon membrane (Hybond N; Amersham) using an alkaline 0.4 N NaOH elution buffer. Probe labeling, hybridization, and detection were performed using the chemiluminescent DIG High prime DNA labeling and detection kit II according to the protocols of the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim).

RNA techniques.

Total RNA was isolated from 7 × 109 cells of wild-type P. fluorescens F113 and mutant derivatives grown for 18 h in minimal medium with sucrose as the carbon source using the RNeasy total RNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen) (14). Northern blot analysis was performed by capillary transfer of 20 μg of total RNA from a 2% agarose gel with 0.66% formaldehyde onto a positively charged nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham) using 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) buffer. Probe labeling was carried out by end labeling primers P3 and P4 with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Ltd.) and [γ-32P]ATP followed by PCR amplification using pCU305 as the template. The resulting 228-bp PCR product containing the prrB gene was purified using a High-pure-PCR purification kit (Boehringer). Hybridization was performed at 65°C overnight in 0.25 M NaH2PO4–7% sodium dodecyl sulfate and washed blots were examined by autoradiography with X-ray film (BIOMAX; Kodak). To measure the size of the PrrB transcript, a 145-bp DNA fragment was PCR amplified using primers P4 and prrBT7 (5′-AATTTAATACGACTCACTATTAGTGTCGACGGATAG-3′) which introduced a T7 promoter upstream of the prrB gene. Subsequently, in vitro transcription of this template was performed using a T7-Megashortscript kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the resulting RNA transcript was used as a size marker in Northern blot analysis.

Primer extension was performed by the method of Pujic et al. (29) with the following modification: 250 pmol of primer prrBSP1 (5′-GTTTGACCCGCCCACATTTTT-3′), which hybridized 126 nucleotides downstream of the TAATA sequence, was end labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. Labeled primer and total RNA were hybridized at 65°C for 5 min and allowed to cool at room temperature for 1 h and 30 min. Reverse transcription was performed at 42°C for 1 h using reverse transcriptase (avian myeloblastosis virus) (Boehringer).

Nucleotide sequence determination and sequence analysis.

The nucleotide sequence of the prrB region was determined by primer walking using an Applied Biosystems PRISM 310 Automated Genetic Analyser (Perkin Elmer). The sequence data were assembled using DNASTAR software package (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis.) and analyzed using the University of Wisconsin Genetic Computer Group (GCG) program FASTA (26) and BLAST (1) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, Md.).

RESULTS

Identification of a locus that restores Phl, HCN, and exoprotease production to gacS and gacA mutants.

To isolate genes capable of complementing the P. fluorescens F113 gacS and gacA mutants, a BamHI plasmid library cloned in the BHR plasmid pSUP106 (36) was mobilized into the F113gacS mutant strain FL33 (8) and screened for restoration of Phl production using the standard Bacillus bioassay (11). Plasmids which restored the Phl-synthesizing ability to FL33 were introduced into the F113 gacA mutant, FG9, and transconjugants in both strains were further characterized for protease and HCN production using the standard bioassays (see references 9 and 38, respectively). A single plasmid, pCU300, was identified which restored Phl, HCN, and protease production to both mutant strains FL33 and FG9.

To further define the region responsible for multicopy suppression of the mutant phenotypes, restriction fragments from the pCU300 insert were subcloned in the BHR vector pBBR1MCS (16), and derivatives were then screened to identify the smallest cloned fragment which could complement both the FL33 and FG9 mutant phenotypes. A 2.8-kb subclone of pCU300 in pBBR1MCS, designated pCU301, complemented the mutant phenotypes. pCU301 contained an essential SalI site in that two BamHI-SalI subclones of pCU301 (pCU302 and pCU303) did not complement FL33 and FG9. In order to determine a more precise location of the region required for phenotypic complementation of the mutants, a 850-bp region of pCU301 was PCR amplified using the primers P1 and P2. The PCR product was cloned into pBBR1MCS as a HindIII-EcoRV fragment to form pCU304, and this plasmid was found to restore Phl and HCN production to both FL33 and FG9 mutants (Fig. 1) and also significantly increased levels of Phl and HCN in the wild-type F113 when introduced in trans.

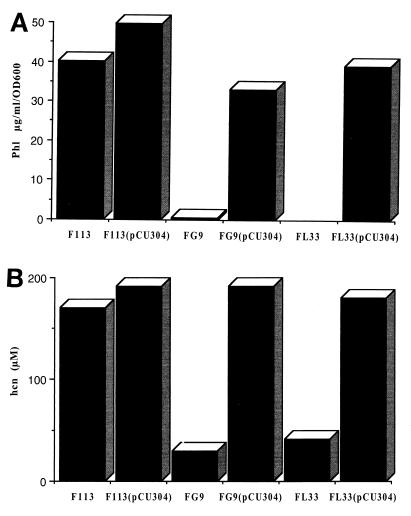

FIG. 1.

Effect of pCU304 on Phl (A) and HCN (B) production by wild-type F113 and F113gacS (FL33) and F113gacA (FG9) mutants. Introduction of the plasmid pCU304 in trans into both FL33 and FG9 mutants restored Phl and HCN production and increased Phl and HCN production in the wild type.

The HindIII-EcoRV fragment from pCU304 was also subcloned into the multiple cloning site of the promoter-probe vector pMP220 (37). This vector was originally constructed so as to have no exogenous promoter activating transcription through the multiple cloning site and also exists in P. fluorescens in low copy (approximately one to five copies) (37). The pMP220 derivative was conjugated into strains FL33 and FG9, and transconjugants did not produce Phl, HCN, or exoprotease when assessed using standard bioassays (data not shown). This shows that prrB, under the control of its own promoter, does not complement the mutant phenotype of FL33 and FG9 and strongly suggests that prrB expression is under GacA-GacS control.

Nucleotide sequence and characterization of the complementing locus.

The 850-bp HindIII-EcoRV subclone was completely sequenced in both directions using universal primers and a primer walking strategy. Comparison with nonredundant nucleotide and protein databases using FASTA (26) and BLAST (1) protocols did not show any obvious homologues. Furthermore, none of the putative open reading frames determined using DNASTAR software had identifiable ribosome binding sites or exhibited typical Pseudomonas codon usage (24).

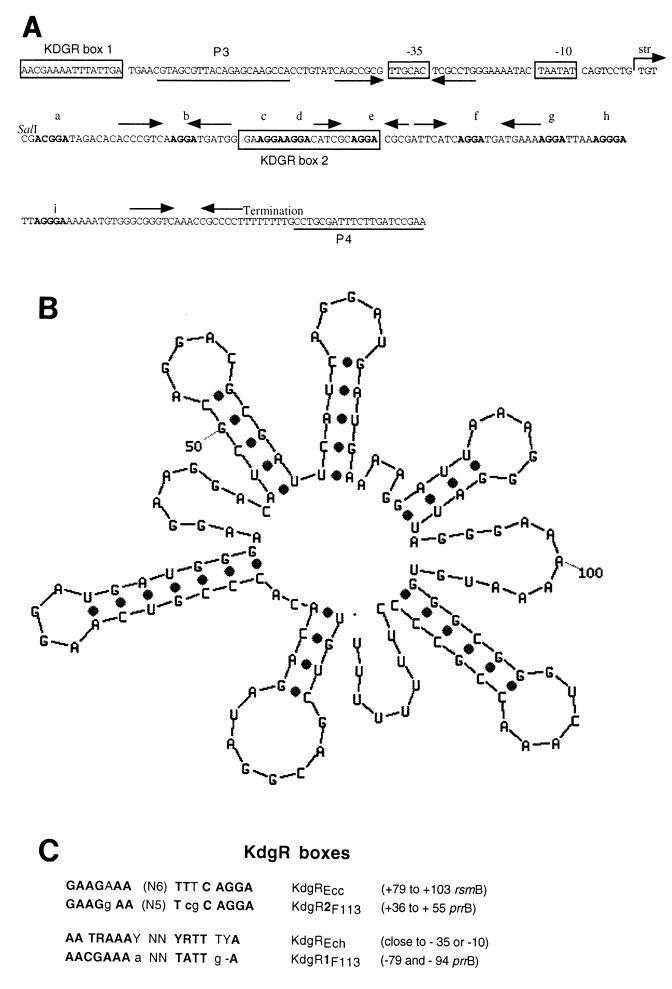

Phenotypic complementation analysis with pCU301, pCU302, and pCU303 subclones, however, revealed that the region immediately surrounding the SalI site was essential for complementing F113 gacS and gacA mutant phenotypes. Sequence analysis of this region revealed a candidate gene that spanned the SalI site and contained putative −10 and −35 sites and a Rho-independent terminator sequence. Located within the sequence were numerous imperfect repeats of the consensus sequence 5′-AGGA-3′ (Fig. 2A). The predicted RNA was surveyed using mfold (39). Results of this analysis revealed a complex secondary structure featuring multiple putative stem-loop structures. The 5′-AGGA-3′ consensus sequences were positioned at the end of predicted hairpin loops distributed throughout the molecule and in single-stranded segments between the loops (Fig. 2B). Excluding the apparent Rho-independent terminator, four of five hairpin loop structures contained the consensus sequence. This structure resembles that of the carbon storage regulatory RNA (CsrB) of E. coli (20) and the regulatory RNA (RsmB) of Erwinia carotovora (22). To determine whether this putative gene was sufficient for the suppression of the F113 gacS and gacA mutations in trans, the candidate gene was PCR amplified using primers P3 and P4 (Fig. 2A) and cloned into pBBR1MCS such that the −35 region was immediately downstream of the plasmid-encoded Plac promoter. The resulting construct pCU305 was conjugated into FL33 and FG9 and found to restore Phl, exoprotease, and HCN production using standard bioassays (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

(A) Nucleotide sequence of prrB. The first line of the sequence shows the transcription start (str) and promoter organization; −10 and −35 sequences are boxed. Putative KDGR recognition sites are boxed. The potential hairpin loop structures are identified by arrows and the 5′-AGGA-3′ imperfect repeat motifs are in boldface type. The nucleotide sequence of primers P3 and P4 used for the construction of pCU305 are underlined. (B) Secondary structure prediction for PrrB RNA generated using mfold. Note that all the repeated elements are predicted to reside in the single-stranded regions and five of the nine are specifically found in the hairpin stem-loop. (C) Nucleotide sequence alignment of Erwinia KdgR boxes with putative prrB KdgR sequences.

Northern analysis revealed a small RNA molecule that is regulated by GacS-GacA.

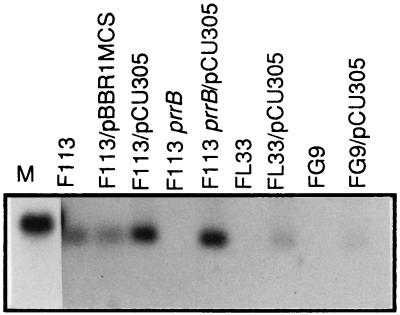

To determine whether pCU305 encoded an RNA transcript, Northern analysis was conducted with P. fluorescens F113 and the mutant strains FL33 and FG9 in the presence and absence of pCU305. Total cellular RNA was isolated from late-log-phase cultures of F113, F113/pBBR1MCS, F113/pCU305, FL33, FL33/pCU305, FG9, and FG9/pCU305 and was probed with the radiolabeled 228-bp fragment amplified from pCU305 using P3 and P4 primers. Northern blot hybridization with this probe detected a single major transcript of approximately 130 nucleotides which was present in F113, F113/pBBR1MCS, F113/pCU305, FL33/pCU305, and FG9/pCU305 but not expressed in FL33 and FG9 mutant backgrounds (Fig. 3). The putative Pseudomonas regulatory RNA molecule was designated PrrB RNA. Increased prrB transcript levels were observed in the wild type F113 and F113prrB mutant in the presence of pCU305 compared with FL33/pCU305 and FG9/pCU305. It was also interesting to note that FG9/pCU305 produced less prrB transcript than FL33/pCU305.

FIG. 3.

Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from 7 × 109 cells of wild-type P. fluorescens F113 and mutant derivatives grown for 18 h in minimal medium with sucrose as the carbon source. The wild type and mutants used are indicated above the lanes. Lane M contains an RNA marker of 145 bases obtained by in vitro transcription. The exposure time for the RNA marker was reduced in order to reduce the band intensity.

Determination of the transcription start site of PrrB RNA and identification of potential promoter elements.

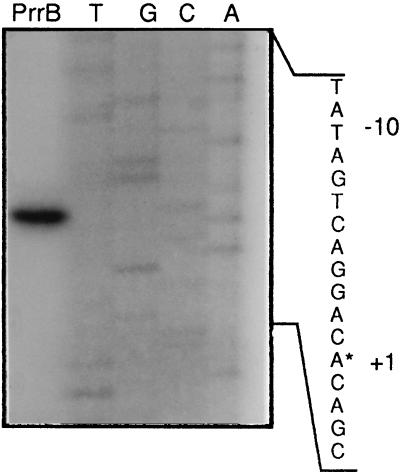

To identify the promoter responsible for prrB transcription, total RNA isolated from wild-type P. fluorescens F113 grown in minimal medium with sucrose as the carbon source was subjected to primer extension analysis (29). This analysis revealed only one specific transcript starting with the 5′ sequence TGT and identifying the transcriptional start site 9 bases downstream of the putative −10 TAATAT promoter sequence (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Mapping of the transcription start site of prrB. A 22-nucleotide primer (prrBSP1) complementary to sequence between positions −126 and −104 from the TAATAT sequence was 5′ end labeled and hybridized to total RNA isolated from the wild-type strain F113. The hybrid was extended using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase, and the extension product was resolved by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. The PrrB lane contains the extension product; the T, G, C, and A lanes contain the sequencing product obtained using prrBSP1. The transcription start site is indicated by an asterisk.

Further analysis of the sequence upstream of the transcription start site revealed inverted repeat sequences surrounding the −35 site (Fig. 2A). It is noteworthy that the inverted repeat sequences lie in close proximity to the RNA polymerase recognition sequence of the promoter.

Sequences upstream of the rsmB gene of E. carotovora contain three binding sites recognized by the regulatory protein KdgREcc (23). KdgREcc negatively regulates rsmB at the transcriptional level. Sequence analysis of the coding region of prrB revealed a sequence homologous to the KdgREcc consensus sequences (Fig. 2A and C). Furthermore, a sequence between positions −77 and −93 from the transcription start site of prrB is highly similar to the known consensus sequence recognized by KdgREch. KdgREch is a repressor that negatively regulates expression of many genes involved in pectinolysis and pectinase secretion in Erwinia chrysanthemi (25).

Construction of a PrrB mutant of P. fluorescens F113.

In order to disrupt prrB, a SmaI Ω-Tc fragment from pHP45Ω-Tc (27) was blunt end ligated within the internal SalI site in the BamHI-XhoI fragment from pCU300 and cloned in the NHR vector pK18 (28). This suicide construct, pCU306, was electroporated into P. fluorescens F113, and double-crossover recombinants were selected as being Tcr and Kms. The presence of the Ω-Tc insertion within the prrB gene of the mutant F113prrB was confirmed by Southern hybridization analysis (data not shown). A PrrB-negative phenotype was demonstrated by Northern hybridization analysis when total cellular RNA was isolated from late-log-phase cells and probed with the 228-bp fragment of pCU305 (Fig. 3). The PrrB transcript was restored in the prrB mutant when pCU305 was introduced in trans.

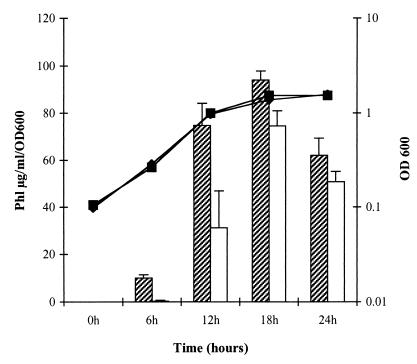

In qualitative plate assays, the prrB mutant FRB1 did not display obvious changes in Phl, HCN, or exoprotease production from that of the wild type (data not shown). However, quantitative assays showed that there was a significant decrease in Phl production by the F113prrB mutant during the mid- to late log phase of growth (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Time course of Phl production by the F113prrB mutant compared with that of the wild type. There was a significant reduction in Phl production during the mid- to late log phase of growth. Phl production of wild-type F113 ( ) and F113prrB (▭) is shown by the bars and the left y axis, and OD600 of wild-type F113 (■) and F113prrB (⧫) is shown by the curves and the right y axis.

) and F113prrB (▭) is shown by the bars and the left y axis, and OD600 of wild-type F113 (■) and F113prrB (⧫) is shown by the curves and the right y axis.

DISCUSSION

A novel gene, prrB, has been identified in the biocontrol strain P. fluorescens F113. The prrB gene was found to restore the production of Phl, HCN, and protease to gacS and gacA mutants of P. fluorescens F113. From sequence analysis, prrB is not predicted to encode a protein but was demonstrated to synthesize a small RNA molecule (PrrB RNA) which may act as a regulatory RNA molecule.

Northern analysis suggested that prrB is regulated, directly or indirectly, through the GacS-GacA two-component signal transduction system (Fig. 3), as the PrrB transcript was not detectable in either the gacA or gacS mutant. Also, when cloned in the promoterless vector, prrB did not restore secondary metabolite production in either the gacS or gacA mutant. The lower levels of prrB transcript produced by FL33/pCU305 and FG9/pCU305 compared with that of the wild-type F113 and F113prrB mutant in the presence of pCU305 may also reflect a role for GacA and GacS in the regulation of prrB.

It was interesting to note that FG9/pCU305 produced less prrB transcript than FL33/pCU305. The reason for this is unclear but could suggest uncoupling of GacA and GacS regulation in relation to prrB. To date, the mechanism of regulation by the GacA-GacS two-component system has not been completely elucidated, and although GacA has a putative DNA binding helix, the target promoters recognized by activated GacA have yet to be demonstrated. Furthermore, analysis of secondary metabolite regulation in P. aeruginosa (30) predicts that this two-component system may activate target genes through a complex regulatory cascade. Phenotypic complementation of gacS and gacA mutants by PrrB RNA suggests that PrrB may function as a regulator within a P. fluorescens GacS-GacA regulatory cascade. However, although inactivation of prrB reduces Phl and HCN production, this did not prevent synthesis of Phl, HCN, or exoprotease. Thus, PrrB RNA does influence secondary metabolite synthesis but not strongly and could be in response to some extra- or intracellular signal or as a stress response. It was interesting that the F113prrB mutant exhibited delayed Phl production, predicting that PrrB RNA may be involved in the early induction of certain secondary metabolite biosynthesis. The prrB dosage experiments mimic, to a degree, results obtained for P. aeruginosa GacA gene dosage experiments (30). In P. aeruginosa, inactivation of gacA resulted in temporal delay (an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 1.2) and reduction of cyanide production. Conversely, when gacA is overexpressed, cyanide production starts much earlier at an OD600 of 0.1. Similarly, in F113, inactivation of prrB delays Phl production (Fig. 5), and in the presence of more copies of prrB, Phl production is induced to maximum levels at low cell density (8).

Recently, Blumer et al. (2) demonstrated that in P. fluorescens CHAO, the GacA-GacS two-component system can mediate posttranscriptional regulation possibly via a recognition site overlapping the ribosome binding site. They also identified a repressor protein RsmA that can recognize the same site, suggesting that RsmA is a downstream regulatory element of the GacA-GacS control system. A RsmA repressor protein was originally identified in E. carotovora and was found to regulate secondary metabolite synthesis and ohlI (AHL synthase) expression (4, 7); this protein was homologous to CsrA, which regulated carbon storage in E. coli (19, 21). CsrA and RsmA were found to bind to cognate regulatory RNA molecules; CsrB is a 350-nucleotide regulatory RNA identified in E. coli (20), and RsmB (previously AepH) is a 259-nucleotide regulatory RNA in E. carotovora (22). It is proposed that binding to CsrB and RsmB antagonizes the regulatory activity of CsrA and RsmA, respectively. This mechanism of RNA-protein interaction has not, as yet been described in Pseudomonas species; however, the recent identification of an RsmA homologue in P. fluorescens CHAO suggests that this regulatory mechanism may exist.

In this study, the secondary structure of the prrB RNA was generated by mfold software (Fig. 2B). The structure is noteworthy for eight stem-loops with the most striking feature being the presence of imperfect 5′-AGGA-3′ repeats found predominantly in the ends of hairpin loops distributed throughout the RNA molecule and in single-stranded regions between the hairpins. This structure is similar to the regulatory RNA molecules RsmB and CsrB. It is noteworthy however, that although the secondary structure of PrrB RNA is similar to RsmB, there is little nucleotide sequence homology. Furthermore, primer extension, Northern, and sequence analyses suggested the size of the PrrB RNA molecule to be approximately 130 bases, considerably smaller than RsmB. Nevertheless, the structural similarity of PrrB with CsrB and RsmB suggests that PrrB may function in F113 in a mechanism similar to RsmB through abrogating the action of an as yet unidentified repressor of secondary metabolite synthesis. The high similarity between sequences of the repressor molecule RsmA, recently isolated from P. fluorescens CHAO (2), and CsrA (E. coli) (21) and RsmA (E. carotovora) (7) suggest that PrrB RNA is likely to interact with a RsmA-like molecule in F113.

It was interesting to note the presence of a consensus KdgREch recognition sequence upstream of the PrrB transcription start site and a KdgREcc site within the coding region of prrB. Extensive work in E. carotovora, E. chrysanthemi, and E. coli has established that KdgR is a general repressor of genes involved in pectinolysis, pectinase secretion, and also other genes including rsmB (23, 25). Our finding suggests that an as yet unidentified gene product similar to KdgR could negatively regulate prrB expression in P. fluorescens F113. If this were true, it would be prudent to investigate if KdgR is also involved in the GacA-GacS regulatory cascade.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Simon Aarons and Abdelhamid Abbas contributed equally to this work.

We thank Mary O'Connell-Motherway, Pat Higgins, and Liam Burgess for advice and technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants awarded by the Irish Health Research Board (to F.O. and S.A.), the Higher Education Authority (HEA) (to F.O.), the Irish Science and Technology Agency Forbairt (to F.O.), and the European Commission (BIO4-CT96-0027, BIO4-CT96-0181, FMRX-CT96-0039, BIO4-CT97-2227, and BIO4-CT98-0254).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D L. Basic local alignment tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumer C, Heeb S, Pessi G, Haas D. Global GacA-steered control of cyanide and exoprotease production in Pseudomonas fluorescens involves specific ribosome binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14073–14078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castric K F, Castric P A. Method for the rapid detection of cyanogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:701–702. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.2.701-702.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee A, Cui Y, Liu Y, Dumenyo C K, Chatterjee A K. Inactivation of rsmA leads to overproduction of extracellular pectinases, cellulases, and proteases in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora in the absence of the starvation/cell density-sensing signal, N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1959–1967. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1959-1967.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen W, Kuo T. A simple method for the preparation of gram negative bacterial genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2260. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.9.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corbell N, Loper J E. A global regulator of secondary metabolite production in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6230–6236. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6230-6236.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui Y, Chatterjee A, Liu Y, Dumenyo C K, Chatterjee A K. Identification of a global repressor gene, rsmA, of Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora that controls extracellular enzymes, N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone, and pathogenicity in soft-rotting Erwinia spp. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5108–5115. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5108-5115.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delany I R. Genetic analysis of the production of the antifungal metabolite 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol by the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens F113. Ph.D. thesis. Cork, Ireland: National University of Ireland; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunne C, Crowley J J, Möenne-Loccoz Y, Dowling D N, de Bruijn F J, O'Gara F. Biological control of Pythium ultimum by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia W81 is mediated by an extracellular proteolytic activity. Microbiology. 1997;143:3921–3931. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farinha M A, Kropinski A M. High efficiency electroporation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using frozen cell suspensions. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;70:221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb13982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenton A M, Stephens P M, Crowley J, O'Callaghan M, O'Gara F. Exploitation of gene(s) involved in 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol biosynthesis to confer a new biocontrol capability to a Pseudomonas strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3873–3878. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.3873-3878.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figurski D H, Helinski D R. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaffney T D, Lam S T, Ligon J, Gates K, Frazelle A, Di Miao J, Hill S, Goodwin S, Torkewitz N, Allshouse A M, Kempf H-J, Becker J O. Global regulation of expression of antifungal factors by a Pseudomonas fluorescens biological control strain. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1994;7:455–463. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-7-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg M E. Preparation and analysis of RNA. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D M, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates; 1989. p. 4.0.1-4.10.8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitten T, Willis D W. Suppression of a sensor kinase-dependent phenotype in Pseudomonas syringae by ribosomal proteins L35 and L20. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1548–1555. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1548-1555.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laville J, Voisard C, Keel C, Maurhofer M, Défago G, Haas D. Global control in Pseudomonas fluorescens mediating antibiotic synthesis and suppression of black root rot of tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1562–1566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao C H, McCallus D E, Wells J M, Tzean S-S, Kang G Y. The repB gene required for production of extracellular enzymes and fluorescent siderophores in Pseudomonas viridiflava is an analog of the gacA gene of Pseudomonas syringae. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:177–182. doi: 10.1139/m96-026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu M-Y, Gui G, Wei B, Preston III J F, Oakford L, Yüksel U, Giedroc D P, Romeo T. The RNA molecule CsrB binds to the global regulatory protein CsrA and antagonises its activity in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17502–17510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu M-Y, Romeo T. The global regulator CsrA of Escherichia coli is a specific mRNA-binding protein. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4639–4642. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4639-4642.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu M-Y, Yang H, Romeo T. The product of the pleiotropic Escherichia coli gene csrA modulates glycogen biosynthesis via effects on mRNA stability. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2663–2672. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2663-2672.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Cui Y, Mukherjee A, Chatterjee A K. Characterisation of a novel RNA regulator of Erwinia carotovora ssp. carotovora that controls production of extracellular enzymes and secondary metabolites. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:219–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Jiang G, Cui Y, Mukherjee A, Ma W L, Chatterjee A K. kdgREcc negatively regulates genes for pectinases, cellulase, protease, hairpinEcc, and a global RNA regulator in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2411–2422. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2411-2421.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minton N P, Atkinson T, Brunton C J, Sherwood R F. The complete nucleotide sequence of the Pseudomonas gene coding for carboxypeptidase G2. Gene. 1984;31:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasser W, Reverchon S, Condemine G, Robert-Baudouy J. Specific interactions of Erwinia chrysanthemi KdgR repressor with different operators of genes involved in pectinolysis. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:427–440. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prentki P, Krisch H M. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pridmore R D. New and versatile cloning vectors with kanamycin resistance marker. Gene. 1987;56:309–312. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pujic P, Dervyn R, Sorokin A, Ehrlich S D. The kdgRKAT operon of Bacillus subtilis: detection of the transcript and regulation by the kdgR and ccpA genes. Microbiology. 1998;144:3111–3118. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reimmann C, Beyeler M, Latifi A, Winteler H, Foglino M, Lazdunski A, Haas D. The global activator GacA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO positively controls the production of the autoinducer N-butyryl-homoserine lactone and the formation of virulence factors pyocyanin, cyanide, and lipase. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:309–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3291701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rich J J, Kinscherf T G, Kitten T, Willis D K. Genetic evidence that the gacA gene encodes the cognate response regulator for the lemA sensor in Pseudomonas syringae. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7468–7475. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7468-7475.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sacherer P, Défago G, Haas D. Extracellular protease and phospholipase C are controlled by the global regulator gene gacA in the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;116:155–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scler F M, Baker R. Effects of Pseudomonas putida and a synthetic iron chelator on induction of soil suppressiveness to Fusarium wilt pathogens. Phytopathology. 1982;72:1567–1573. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shanahan P, O'Sullivan D J, Simpson P, Glennon J D, O'Gara F. Isolation of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol from a fluorescent pseudomonad and investigation of physiological parameters influencing its production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:353–358. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.353-358.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon R, Priefer V, Pühler A. Vector plasmids for in vivo and in vitro manipulations of Gram negative bacteria. In: Pühler A, editor. Molecular genetics of the bacteria-plant interactions. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1983. pp. 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spaink H P, Okker R J H, Wiffelman C A, Pees E, Lugtenberg E J J. Promoters in the nodulation region of the Rhizobium leguminosarum Sym plasmid pRL1J1. Plant Mol Biol. 1987;9:27–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00017984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voisard C, Keel C, Haas D, Défago G. Cyanide production of Pseudomonas fluorescens helps suppress black root rot of tobacco under gnotobiotic conditions. EMBO J. 1989;8:351–358. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuker M, Jaeger J A, Turner D H. A comparison of optimal and suboptimal RNA secondary structure predicted by free energy minimalisation with structures determined by phylogenetic comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2707–2714. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.10.2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]