Abstract

Our work provides evidence that a sequence characteristic of FNR binding sites, when interacted with by a trans-acting factor, activates anaerobic transcription of the nifLA operon in Enterobacter cloacae. DNA gyrase activity has been found to be important for the anaerobic transcription of the nifLA promoter. Our results suggest that anaerobic regulation of the nifLA operon is mediated through the control of the promoter region-binding trans-acting factor at the transcriptional level, while DNA supercoiling functions in providing a topological requirement for the activation of transcription.

In the nitrogen-fixing (nif) enteric bacteria Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae, the nif genes are regulated by the activity of the ntrC, ntrA, nifA, and nifL genes at the transcriptional level (2, 3, 4, 24). nifL and nifA constitute an operon which is regulated by the product of ntrC or autoregulated by the product of nifA, NifA (5, 9). NifA acts as a positive regulator in conjunction with NtrA to activate nif genes (19), while the product of nifL, NifL, acts as a repressor of nif genes under oxygen or in an excess of fixed nitrogen (13).

Our previous investigations showed that the nifLA promoter is highly sensitive to oxygen and that NifA is inactivated by NifL under oxygen (5, 15, 23). Accordingly, we hypothesized that nif regulation by oxygen is mediated at two different levels. First, at the transcriptional level, the oxygen sensitivity of the nifLA promoter ensures that the nifLA promoter and, hence, all other nif promoters are repressed by oxygen; second, at the posttranslational level, NifL interacts with NifA in the presence of oxygen. As the result of a shortage of active NifA, the expression of other nif genes is blocked.

Direct interaction of NifL and NifA has been demonstrated by the two-hybrid system test (16, 23). As to the question of aerial regulation of the nifLA promoter, most investigators have claimed that neither FNR nor the oxrC gene product is involved in the expression of nifLA in response to oxygen (14). Since the activity of the K. pneumoniae nifLA promoter can be prevented by inhibition of DNA gyrase activity, they thus held that aerobic-anaerobic regulation of the nifLA promoter is mainly mediated through the level of DNA supercoiling (6, 8). Our present work demonstrated that an upstream sequence of the nifLA promoter characteristic of the FNR binding sequence, when bound by the trans-acting factor from the bacterial cells, activates anaerobic expression of the nifLA operon. We also proved that DNA gyrase is truly important for anaerobic transcription of the nifLA promoter. A mechanism for aerobic regulation of the nifLA promoter is proposed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. cloacae E26 | Wild type | 20 |

| E. coli | ||

| CJ236 | dut-1 ung-1 thi-1 relA1/pCJ105(camrF′) | 21 |

| JM105 | supE endA sbcB15 hsdR4 rpsL thi Δ(lac-proA) F′ [traD36 proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15] | 21 |

| JM110 | dam dcm supE44 endA1 hsdR17 thi leu rpsL lacY galK galT ara tonA thr tsx Δ(lac-proAB) F′ [traD36 proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15] | 21 |

| YMC9 | endA1 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 ΔlacU169 fnr+ crp+ gyr+ | 19 |

| DH5α | supE44ΔlacU169(φ80lacZΔM15) fnr+ crp+ hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 21 |

| JRG2865 | Δ(tyrR-fnr-rac-trg)17 zdd-230::Tn9Δcrp Δ(lacIPOZYA)X74 galU galK rpsL | 12 |

| Plasmids | ||

| M13mp19 | Sequencing vector | 21 |

| M13mp19-nifLAp | E. cloacae nifLAp (SphI-HaeIII fragment) in M13mp19 | This work |

| M13mp19-nifLAp-D | E. cloacae nifLAp (SphI-HaeIII fragment) in M13mp19; FNR site consensus sequence deleted [Δ(HpaI-BglI)] | This work |

| M18mp19-nifLAp-m1 | E. cloacae nifLAp in M13mp19; FNR site consensus sequence mutated to CCGAT CTGG GGCCC | This work |

| M13mp19-nifLAp-m2 | E. cloacae nifLAp in M13mp19; FNR site consensus sequence mutated to CCGAT CTGG ATCGA | This work |

| pUC18 | Cloning vector | 21 |

| pUC18-nifLAp-mc | E. cloacae nifLAp-lacZ fusion in pGD926; T−111, C−112, and C−121 mutated to G−111, T−112, and G−121 | This work |

| pGD926 | Tcr IncP lacZ fusion vector | 7 |

| pPW926 | E. cloacae nifLAp-lacZ fusion in pGD926; FNR site consensus sequence is CCGAT CTGG ATCAA | This work |

| pPW-D926 | E. cloacae nifLAp-lacZ fusion in pGD926; ΔHpaI-BglI (FNR site consensus sequence deleted) | This work |

| pAP926 | E. cloacae nifLAp-lacZ fusion in pGD926; FNR site consensus sequence mutated to CCGAT CTGG GGCCC | This work |

| pCL926 | E. cloacae nifLAp-lacZ fusion in pGD926; FNR site consensus sequence mutated to CCGAT CTGG ATCGA | This work |

| pST926 | E. cloacae nifLAp-lacZ fusion in pGD926; base pairs T−111, C−112, and C−121 mutated to G−111, T−112, and G−121 | This work |

| pMK90 | E. coli gyrA cloned in pKC16 | 18 |

| pMK47 | E. coli gyrB cloned in pKC16 | 18 |

| pDO531 | K. pneumoniae nifLAp-lacZ fusion in pRK248 | 9 |

DNA manipulations.

Preparation of plasmids DNA, endonuclease digestion, ligation, and transformation were carried out essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (21).

Construction of nifLA promoter mutants.

Initially, the E. cloacae nifLA promoter (Fig. 1) was cloned in vector M13mp19. The resultant clone is referred to as M13mp19-nifLAp. The M13mp19-nifLAp DNA was digested with BglI and HpaI, filled in with Klenow polymerase, and ligated to yield M13mp19-nifLAp-D, where the FNR site consensus sequence upstream of the nifLA promoter was deleted. Promoter mutant clones M13mp19-nifLAp-m1 and M13mp19-nifLAp-m2, with a mutation in the FNR site consensus sequence, were constructed by oligonucleotide-mediated mutagenesis as described by Sambrook et al. using a 0.5-kb BamHI-to-HindIII fragment of the nifLA promoter region carried in M13mp19-nifLAp as a target (21). A 26-mer mutant primer (5′AACAGGCGTTAACAGGGCCCAGATCG3′) complementary to bases −63 to −38 with the four most conserved bases mismatched with respect to the FNR consensus was synthesized and used to construct M13mp19-nifLAp-m1. Another 24-mer mutant primer (5′ACAGGCGTTAACATCGATCCAGAT3′) complementary to bases −62 to −39 with one most conserved base mismatched was synthesized and used to construct M13mp19-nifLAp-m2. The 26-mer primer and the 24-mer primer create a unique restriction ApaI or ClaI endonuclease site in each case. It can be used to screen the desired mutants.

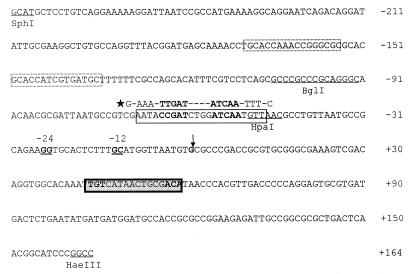

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the E. cloacae nifLA promoter region. The NtrC binding site is shown as a dashed box, the consensus sequence of the FNR site is boxed, the NifA binding site is shadowed, the ς54-RNA polymerase recognition site is double underlined, the transcription start site is indicated by the arrow, and the restriction endonuclease site is underlined. The conserved sequence of the FNR site is indicated by the star.

Promoter mutant clone pUC18-nifLAp-mc, with alteration of base pairs outside the FNR site consensus, was constructed by PCR (1). The first-round PCR was performed with mutant primer 5′GGCGGGCGCTGCAGACGAAATCTGCTGGCG3′, which complements bases −99 to −128 upstream of the nifLA transcription start site, and primer 5′AGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGGA3′, which complements phage M13. The double-stranded product was purified and used as one of the primers in the second-round PCR along with primer 5′GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT3′, which anneals to the other side of M13. M13mp19-nifLAp double-stranded DNA was used as the template in both PCR rounds. The final PCR product containing the mutations was then cloned in vector pUC18 to give rise to pUC18-nifLAp-mc.

All of the mutants obtained as described above were rescreened by DNA sequencing. nifLAp-lacZ translational fusions pPW926, pPW-D926, pAP926, pCL926, and pST926, respectively, were constructed by digesting M13mp19-nifLAp, M13mp19-nifLAp-D, M13mp19-nifLAp-m1, M13mp19-nifLAp-m2, and pUC18-nifLAp-mc with BamHI and HindIII. The resultant 0.5-kb fragments, each of which contains the nifLA promoter region, were then cloned into the same restricted plasmid, pGD926.

Assay of β-galactosidase.

Bacteria were grown aerobically for 24 h at 28°C in nitrogen-free minimal medium supplemented with 0.01% casein hydrolysate, 1 mg of vitamin B1 per liter, 20 mg of glutamine per liter, and appropriate antibiotics (5). Cells were pelleted, washed, and resuspended in the same medium and then grown under aerobic or anaerobic (flashing with nitrogen) conditions for 8 h. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed as described by Miller (17).

DNA binding assay.

Binding of protein to the FNR site consensus sequence was monitored by measuring the reduction in the electrophoretic mobility of the labeled probe DNA fragments as described by Fried and Crothers (11). In a 20-μl total sample volume, 3.5 pmol of an [α-32P]dATP-labeled double-stranded probe was incubated with 14 μg of protein extracts containing 3 μg of calf DNA for 25 min at 25°C. A DNA fragment with the sequence 5′TTAATGCCGTCGAATACCGATCTGGATCAATGTTAACGCCTGTT3′, followed by the nifLA promoter containing the FNR binding site consensus sequence, and a DNA fragment with the sequence 5′TTAATGCCGTCGAATACCGATCTGGGGCCCTGTTAACGCCTGTT3′, followed by the nifLA promoter with the FNR binding site consensus sequence mutated, were synthesized as probes. Protein-DNA complexes were separated by 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then autoradiographed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A sequence upstream of the nifLA promoter and its role in the activity of the nifLA operon.

As reported previously for E. cloacae E26, there are three cis-acting elements residing in the region upstream of the nifLA operon: the ς54-RNA polymerase recognition site at −24 to −12, the NtrC binding site at −171 to −135, and the NifA binding site at positions +44 to +59 from the transcription start site (TSS) (5). Through analysis of the DNA sequence of the nifLA promoter, we found a sequence, CCGAT-N4-ATCAA, at positions −69 to −48 from the TSS (Fig. 1) which is characteristic of the sequence of an FNR binding site (10, 22). In order to know the role of this defined sequence in the activity of the nifLA operon under anaerobic conditions, we constructed a promoter mutant with a 48-bp BglI-to-HpaI fragment including the consensus FNR binding site upstream of the TSS deleted and cloned it into plasmid pGD926 to form a nifLApΔ-lacZ translational fusion. After it was introduced into E. cloacae E26 or Escherichia coli YMC9, the β-galactosidase activity of the fusion was measured. As shown in Table 2, deletion of the consensus FNR binding site caused a marked decrease in the activity of the nifLA promoter under anaerobic conditions. Furthermore, we made promoter mutants by site-directed mutagenesis. One mutant contains the sequence CCGAT CTGG GGCCC, where the conserved sequence ATCAA was changed to GGCCC, and another mutant contains the sequence CCGAT CTGG ATCGA, where the ATCAA sequence was changed to ATCGA. In addition, a mutant with base pairs T−111, C−112, and C−121 outside the FNR binding site consensus sequence changed to G−111, T−112, and G−121 was constructed and used as a control. After these mutants were cloned into pGD926 to form nifLAp-lacZ fusions, their activities were measured. Data in Table 2 show that either deletion or alteration of the sequence of the consensus FNR site produced low activity under anaerobic conditions, whereas mutation at sites outside of this sequence did not affect the anaerobic expression of the fusion (Table 2). These results substantiate the evidence that the consensus FNR site upstream of the nifLA promoter is important for regulation of the nifLA operon.

TABLE 2.

Expression of E. cloacae nifLAp-lacZ fusions in E. cloacae and E. coli strainsa

| Strain (plasmid) | Genotype of relevant host (plasmid) | β-Galactosidase activityb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | N2 | ||

| E. cloacae | |||

| E26(pGD926) | Wild type (promoterless lacZ) | 1 | 3 |

| E26(pPW926) | Wild type (nifLAp-lacZ) | 141 | 1,177 |

| E26(pPW-D926) | Wild type (nifLApΔ-lacZ) | 57 | 91 |

| E26(pAP926) | Wild type (nifLApm1-lacZ) | 139 | 165 |

| E26(pCL926) | Wild type (nifLApm2-lacZ) | 141 | 169 |

| E26(pST926) | Wild type (nifLApmc-lacZ) | 161 | 1,217 |

| E. coli | |||

| YMC9(pGD926) | fnr+ crp+ (promoterless lacZ) | 2 | 3 |

| YMC9(pPW926) | fnr+ crp+ (nifLAp-lacZ) | 127 | 1,296 |

| YMC9(pPW-D926) | fnr+ crp+ (nifLApΔ-lacZ) | 33 | 37 |

| YMC9(pAP926) | fnr+ crp+ (nifLApm1-lacZ) | 125 | 465 |

| YMC9(pCL926) | fnr+ crp+ (nifLApm2-lacZ) | 119 | 290 |

| YMC9(pST926) | fnr+ crp+ (nifLApmc-lacZ) | 178 | 933 |

| JRG2865(pPW926) | Δfnr Δcrp (nifLAp-lacZ) | 129 | 1,439 |

| DH5α(pPW926) | fnr+ crp+ gyrA96 (nifLAp-lacZ) | 3 | 15 |

| DH5α(pPW926, pMK47) | fnr+ crp+ gyrA96 (nifLAp-lacZ gyrBc) | 5 | 12 |

| DH5α(pPW926, pMK90) | fnr+ crp+ gyrA96 (nifLAp-lacZ gyrAc) | 74 | 854 |

β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods, and values are means of results from at least three independent measurements.

In Miller units.

Constitutively expressed.

A trans-acting factor binds to the defined sequence upstream of the nifLA promoter.

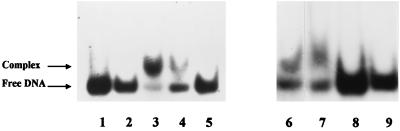

To test if there is a trans-acting factor bound to the defined sequence upstream of the nifLA promoter which enhances the anaerobic expression of the nifLA operon, a gel mobility shift assay was conducted. The fragments encompassing the consensus FNR site or its variants were incubated with the soluble protein extracts from E. cloacae or E. coli and assayed for DNA-protein complex formation. As shown in Fig. 2, a slower-migrating complex was detected following incubation of the probe containing the FNR site consensus sequence with the cell extracts. In contrast, no complex was detected following incubation of the probe containing the mutated consensus sequence of the FNR site with the cell extracts. We thus concluded that a trans-acting factor binding to the FNR consensus sequence is present in E. cloacae and also in E. coli.

FIG. 2.

Gel mobility shift assay of a DNA fragment containing the FNR site consensus sequence incubated with protein extracts from E. cloacae E26 (lanes 2 to 5), E. coli YMC9 (lanes 7 and 9), and E. coli JRG2865 (lane 6). Lanes: 1 and 8, labeled DNA fragment; 2, 3, 6, and 7, labeled DNA fragment incubated with protein extract from anaerobic culture; 4, labeled DNA fragment incubated with protein extract from aerobic culture; 5 and 9, labeled DNA fragment containing mutated FNR site consensus sequence incubated with protein extract from an anaerobic culture. The reaction mixture in lane 2 also contained 300 pmol of unlabeled probe DNA as a specific competitor.

When plasmid pPW926 carrying the E. cloacae nifLAp-lacZ fusion was transferred to E. coli fnr mutant strain JRG2865, which fails to produce FNR, the fusion was just as active as it was in the wild-type E. coli strain (Table 2). As assessed by a gel mobility shift assay using the DNA fragment encompassing the FNR site consensus sequence, followed by incubation with protein extract of E. coli fnr mutant strain JRG2865, a DNA-protein complex was also consistently formed, as it was when the DNA fragment was incubated with the protein extract of the wild-type strain of E. coli (Fig. 2). From these results, we concluded that a trans-acting factor other than FNR binds to the putative FNR site and operates in the expression of the nifLA promoter in E. coli. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that FNR is capable of binding to the consensus sequence of the FNR site to activate the nifLA promoter in E. cloacae.

Superhelical status of DNA and activity of the nifLA promoter.

Before the identification of a regulatory factor responding to oxygen status, it has been reported that the K. pneumoniae nifLA promoter requires a specific degree of negative supercoiling for expression, which is only possible under anaerobic conditions (6, 8). To examine this possibility, we tested influence of gyrase activity on the transcription of the E. cloacae nifLA promoter by introducing the nifLAp-lacZ fusion into an E. coli DH5α gyrA mutant or into gyrA+ strains of E. coli and E. cloacae in the presence of a gyrase inhibitor. The known gyrase-dependent K. pneumoniae nifLAp-lacZ fusion (6, 8) was also run as a control. The results showed that expression of the nifLAp-lacZ fusion has been markedly halted both in the gyrA mutant and in the gyrA+ strains with the presence of the gyrase inhibitors under aerobic or anaerobic conditions (Tables 2 and 3). When a plasmid carrying constitutively expressed gyrA was introduced into the gyrA DH5α mutant harboring the nifLAp-lacZ fusion, the activity of the fusion was restored. However, a gyrB clone did not have the same effect (Table 2). Curiously, the nifH operon of Rhizobium meliloti, which is known to be insensitive to oxygen (unpublished data), appears to be DNA gyrase dependent too. These results confirm the earlier inference that DNA gyrase activity is crucial for transcription of the nifLA operon and possibly other nif genes.

TABLE 3.

Effects of coumermycin A1 and novobiocin on β-galactosidase activities of nifLAp-lacZ translation fusions

These findings have significantly advanced our understanding of the mechanism of oxygen regulation of nifLA transcription. The trans-acting factor, which responds to the redox status, activates the nifLA promoter when bound to the defined sequence upstream of the nifLA promoter, while DNA supercoiling produced by the activity of gyrase functions in providing a topological requirement for the bound trans-acting factors, presumably through the process of looping of DNA between the sites of the NtrC and the trans-acting factors, thus enhancing the cooperative interaction between those bound trans-acting factors for activation of transcription.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. R. Guest for the gift of JRG2865.

This work was supported by grants from the Commission of the European Communities, the National High Technology “863” Programs of China, and the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barik S. Site-directed mutagenesis by double polymerase chain reaction: megaprimer methods. In: White B A, editor. PCR protocols: current methods and applications. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1993. pp. 277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchanan-Wollaston V, Cannon M C, Beynon J L, Cannon F C. Role of the nifA gene product in the regulation of nif expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nature (London) 1981;294:776–778. doi: 10.1038/294776a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchanan-Wollaston V, Cannon M C, Cannon F C. The use of cloned nif (nitrogen fixation) DNA to investigate transcriptional regulation of nif expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;184:102–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00271203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Bruijn F J, Hilgert U, Stigter J, Schneider M, Heiner M A, Klosse U, Pawlowski K. Regulation of nitrogen fixation and assimilation genes in the free living versus symbiotic state. In: Gresshof P M, editor. Nitrogen fixation: achievements and objectives. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1990. pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng X B, Shen S C. Structure and oxygen sensitivity of the nifL promoter of Enterobacter cloacae. Sci China. 1995;38:60–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimri G P, Das H K. Transcriptional regulation of nitrogen fixation genes by DNA supercoiling. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;212:360–363. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ditta G, Schmidhauser T, Yakobson E, Lu P, Liang X W, Finlay D R, Guiney D, Helinski D R. Plasmids related to the broad host range vector, pRK290: useful for gene cloning and for monitoring gene expressing. Plasmid. 1985;13:129–153. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(85)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon R A, Henderson N C, Austin S. DNA supercoiling and aerobic regulation of transcription from the Klebsiella pneumoniae nifLA promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9933–9946. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.21.9933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drummond M, Clements J, Merrick M, Dixon R. Positive control and autogenous regulation of the nifLA promoter in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nature (London) 1983;301:301–307. doi: 10.1038/301302a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eiglmeier K, Honore N, Luchi S, Lin E C C, Cole S T. Molecular genetics analysis of FNR-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:869–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried M, Crothers D M. Equilibria and kinetics of lac repressor-operator interactions by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:6505–6525. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.23.6505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green J, Guest J R. Regulation of transcription at ndh promoter of Escherichia coli by FNR and novel factors. Mol Microbiol. 1993;12:433–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill S, Kennedey C, Kavanagh E, Goldberg R B, Hanau R. Nitrogen fixation gene (nifL) involved in oxygen regulation of nitrogenase synthesis in K. pneumoniae. Nature (London) 1981;290:424–426. doi: 10.1038/290424a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill S. Redox regulation of enteric nif expression is independent of the fnr gene product. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;29:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong Q-T, Wu Q-L, Ma Z-F, Shen S-C. Oxygen sensitivity of the nifL promoter of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:353–356. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.353-356.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei S, Pulakat L, Gavini N. Genetic analysis of nif regulatory genes by utilizing the yeast two-hybrid system detected formation of a NifL-NifA complex that is implicated in regulated expression of nif genes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6535–6539. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6535-6539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J H. Experiment in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. pp. 352–355. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizuuchi K, Mizuuchi M, O'Dea H M, Gellert M. Cloning and simplified purification of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase A and B proteins. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9199–9201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ow D W, Ausubel F M. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism genes by nifA gene product in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nature (London) 1983;301:307–313. doi: 10.1038/301307a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu Y S, Zhou S P, Mo X Z, Ye S G, Cai X W, Ma C L, Mao C A, Chen Y H, He S Y, Deng R F. Study of nitrogen fixation bacteria associated with rice root: the characteristics of nitrogen fixation by Alcaligenes faecalis strain A15 and Enterobacter cloacae strain E26. Acta Microbiol Sin. 1981;21:473–475. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawers G, Kaiser M, Sirko A, Freundlich M. Transcriptional activation by FNR and CRP: reciprocity of binding-site recognition. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:835–845. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2811637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao H, Zhu J, Shen S C. NifL, an antagonistic regulator of NifA interacting with NifA. Sci China. 1998;41:303–308. doi: 10.1007/BF02895106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu J-B, Li Z-G, Wang L-W, Shen S-S, Shen S-C. Temperature sensitivity of a nifA-like gene in Enterobacter cloacae. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:357–359. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.357-359.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]