Abstract

The complete sequence of the virulence plasmid pMT1 of Yersinia pestis KIM5 revealed a region homologous to the plasmid partition (par) region of the P7 plasmid prophage of Escherichia coli. The essential genes parA and parB and the downstream partition site gene, parS, are highly conserved in sequence and organization. The pMT1parS site and the parA-parB operon were separately inserted into vectors that could be maintained in E. coli. A mini-P1 vector containing pMT1parS was stably maintained when the pMT1 ParA and ParB proteins were supplied in trans, showing that the pMT1par system is fully functional for plasmid partition in E. coli. The pMT1par system exerted a plasmid silencing activity similar to, but weaker than those of P7par and P1par. In spite of the high degree of similarity, especially to P7par, it showed unique specificities with respect to the interactions of key components. Neither the P7 nor P1 Par proteins could support partition via the pMT1parS site, and the pMT1 Par proteins failed to support partition with P1parS or P7parS. Typical of other partition sites, supernumerary copies of pMT1parS exerted incompatibility toward plasmids supported by pMT1par. However, no interspecies incompatibility effect was observed between pMT1par, P7par, and P1par.

Yersinia pestis causes bubonic plague, an acute lethal disease of humans. Strain KIM5 contains three plasmids, pCD1 (70,504 bp), pPCP1 (9,610 bp), and pMT1 (100,984 bp). The presence of the latter two plasmids in most Y. pestis strains distinguishes them from Yersinia species that cause chronic enteric disease (9). The complete sequence of all three plasmids from Y. pestis KIM5 has been determined (15, 17). The largest plasmid, pMT1, carries some important virulence factors, including murine toxin and F1 capsular antigen (17, 31). Its sequence reveals open reading frames for a number of proteins with homologs of known function (15, 17). These include an operon encoding ParA and ParB proteins homologous to the ParA and ParB partition proteins of the plasmid prophage of bacteriophage P7 (19), which, by acting at the downstream parS partition site, promote active partition of the plasmid in Escherichia coli (15, 17).

The P7 ParA and ParB proteins are members of a family of protein pairs that are implicated in the partition of plasmid or chromosomal DNA in a wide variety of prokaryotes (23, 28). The best-studied members of these Par protein families are the ParA and ParB proteins of P1 and the SopA and SopB proteins of plasmid F from E. coli. The genes for these proteins form operons (parA-parB and sopA-sopB) with a partition site (P1parS or FsopC) placed directly downstream from the par open reading frames. (21, 22). Both ParA and ParB are essential for active partition. The ParA protein is an ATPase whose activity is stimulated by ParB and double-stranded DNA (8). It binds as part of a ParA-ParB-parS complex when ATP is continuously supplied (4). The ParB protein binds specifically to parS and does so cooperatively with the integration host factor IHF (7, 10).

Under certain circumstances, ParB binding to parS can nucleate a change in the surrounding DNA sequences that silences gene expression over a wide region (20, 26). This silencing phenomenon can affect certain plasmids containing P1parS. Derivatives of plasmid pGB2 carrying P1parS are not stabilized by the cognate Par proteins like other parS constructs. Rather, the silencing phenomenon drastically destabilizes them so that they cannot be maintained in the presence of the P1 Par proteins (18).

Although the P7par and P1par regions are similar in sequence and organization, they exhibit unique species specificities. The P1 Par proteins do not promote partition of plasmids carrying the P7parS site, nor do the P7 proteins work with P1parS (12). The two partition systems also differ in incompatibility specificity. Extra copies of the P1parS or P7parS site on a second plasmid or in the host chromosome destabilize the parent plasmid. However, they have no effect on the maintenance of the plasmid of the other plasmid species (2).

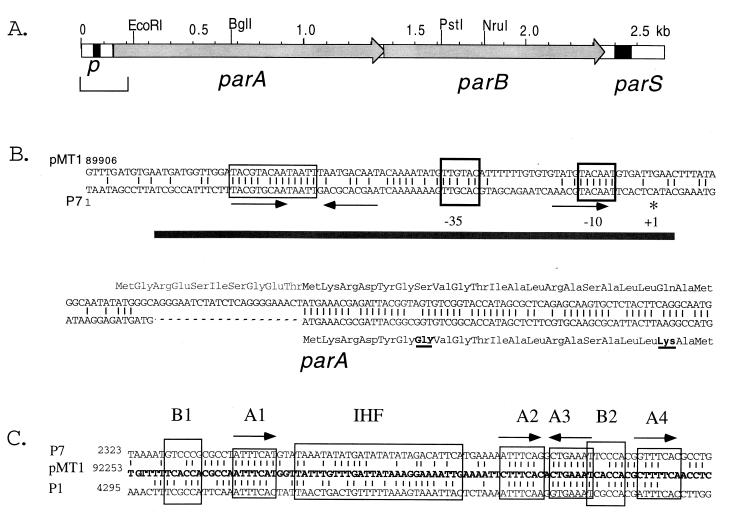

It is probable that species specificity for Par protein recognition and incompatibility specificity have the same root cause. Incompatibility is thought to be due to a competition between parS sites for plasmid pairing or plasmid attachment to some key host structure required for partition (2). If the Par protein complexes at the parS sites of two different plasmids are identical or very similar, the complexes will compete with each other for pairing or attachment. Partition sites such as P7parS and P1parS are sufficiently different that they do not form complexes with the proteins of the other species. Thus, for example, P1parS does not form a complex in the presence of the P7par system and does not compete with it. The specificity differences between P7parS and P1parS are determined by key contacts between ParB and parS which differ between the two species (25). The pMT1 sequence contains a potential parS site downstream of parB which is similar in position and sequence to those of plasmids P7 and P1 (12, 17) (Fig. 1C). The putative pMT1parS site maintains several of the features known to be important for P7parS and P1parS function (17), including the presence of well-conserved heptamer ParB binding boxes (A1, A2, and A3 in Fig. 1) and perfect direct repeats corresponding to the P1 and P7 B1 and B2 discriminator boxes (4, 12) (Fig. 1C). The P1 and P7 discriminator boxes contact ParB and are responsible for the species specificity of ParB recognition by the parS site (12). The discriminator boxes differ between P1 and P7 and are different again in pMT1 (Fig. 1). Here, we characterize the Yersinia pMT1 par system and probe its functional relationships to P7par and P1par with respect to protein recognition and incompatibility.

FIG. 1.

The pMT1par region. (A) Physical map of the pMT1par region showing the likely par promoter, the parA and parB open reading frames, and the parS site. The bracketed sequence is expanded in panel B. (B) Alignment of the upstream sequences and start of the parA open reading frames of P7 and pMT1 (15, 19). The −10 and −35 promoter elements, which are known to constitute the P7par promoter (14), are boxed, as is a well-conserved region upstream of the −35 sequence which lies within P7 operator sequences required for operon autoregulation (14). The gray bar shows the P7 region protected by ParA binding during autoregulation (14). Arrows mark imperfect repeats in the P7 sequence which were thought to be involved in ParA binding (14). An asterisk marks the major transcription start point for P7parA. A possible extension of the pMT1parA open reading frame is shown in gray lettering. (C) The parS sequences of P7, P1, and pMT1 are shown in the same alignment proposed by Lindler et al. (17). The boxed sequences B1 and B2 are the discriminator hexamers which determine the specificity differences between P7parS and P1parS for recognition by the cognate ParB protein (12). The heptamer boxes A1 through A4 are important for ParB binding (11, 12). IHF, integration host factor binding region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods and materials.

General methods and materials were used as previously described (24), unless stated otherwise.

Bacterial strains.

E. coli strain DH5α (27) was used for general DNA manipulations. Strain CC2056 (recA56 trpam thi lacZam λW82) (32) was used for the colony color assay and for incompatibility and plasmid silencing tests.

Plasmids.

Plasmids pALA1413 and pALA1414 are derivatives of plasmid pBR322 (3) which carry the parA-parB operons of P1 and P7, respectively (24). The lambda mini-P1 plasmid λcI857-P1:5RΔ1005 is a version of λcI857-P1:5R (30) that has had the P1par region deleted (1). Plasmids pALA1952 and pALA1993 (24) have the P1parS and P7parS sites, respectively, in a mini-P1 plasmid that carries the supF suppressor gene. Plasmid pALA1991 is similar to these but has no parS site. It was derived from the mini-P1 vector pALA1626 (13) by insertion into the AseI site of the supF gene from the E. coli chromosome as a PCR fragment amplified by PCR with AseI ends. When recombined with λcI857-P1:5RΔ1005 as previously described (32), pALA1952, pALA1993, and pALA1991 gave rise to λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1952, λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1993, and λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1991, respectively.

Plasmid pALA2235 consists of the pMT1 sequence 89646 to 92695, containing the par region obtained as a PCR product with an NdeI extension at the left end, cut with NdeI and HindIII, and inserted between the homologous sites in the vector pET-21a (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.). The PCR primers used were 5′-GTGCCAGTTGTATCGTCTCC and 5′-TAGTGCAATCGCGTTCTGTC, and the template was pMT1 plasmid DNA (15). Using pALA2235 as a template, PCR products were obtained with the following primers: (i) 5′-CGATCGAAGCTTGCCGGAACCCCATTTTGA, (ii) 5′-TAGCAGGATCCTTATCCCTTACTCACCTGATTCTG, (iii) 5′-TAGCAGGATCCGAAAGACTTCCAGAATCAGGTGAG, (iv) 5′-TAGCAGGATCCTGGTCTGAACTGCCAATAGCG, and (v) 5′-TAGCAGGATCCTTTTTCACCACGCCAATTTCATGG.

The product of primers i and ii was digested with HindIII and BamHI, and the resulting fragment was introduced between the matching sites of plasmid pBR322 to give pALA1846, which contains the pMT1parA-parB operon (bp 89651 to 92229). The product of primers iii and iv was digested with BamHI, and the resulting fragment was introduced between the homologous sites of plasmid pALA1991 to give pALA1843, which contains a 190-bp pMT1 fragment (bp 92192 to 92385) including the parS site.

Plasmid pALA1847 was similar to pALA1843, but used primers iv and v and has the 130-bp pMT1parS fragment (bp 92255 to 92385). Plasmids pALA1843 and pALA1847 were recombined as previously described (32) with λcI857-P1:5RΔ1005 to give λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1843 and λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1847.

Plasmids pALA1839 and pALA1838 were made by excising the BamHI-EcoRI fragments of pALA1993 and pALA1952, respectively, and introducing them between the matching sites of plasmid pGB2 (6). Plasmid pALA1840 was made by insertion of the BamHI-EcoRI fragment of pALA1843, which lies downstream of pMT1parS, between the equivalent sites in pGB2, followed by insertion of the BamHI-BamHI fragment of pALA1843 into the BamHI site of the construct. The orientation of the parS sites in pALA1840, pALA1839, and pALA1838 is in the conventional sense (Fig. 1), running clockwise with respect to the pGB2 map (6).

Plasmids pALA1849, pALA1850, and pALA1851 were made by excising the BamHI-EcoRI parS regions of pALA1838, pALA1839, and pALA1840, respectively, and inserting them between the BclI and EcoRI sites of plasmid pACYC184 (5). In the case of pALA1851, this involved the simultaneous introduction of the two adjacent fragments and checking the resulting construct for the conventional orientation of pMT1parS.

The colony color partition assay.

Assays with strain CC2056 were performed by the colony color partition method (24), using pure high-titer lysates of λ-miniP1 constructs carrying chloramphenicol resistance and the parS site (32). The appropriate mini-P1 plasmid containing the respective parS site was incorporated into a λ-P1:5RΔpar phage vector (λcI857-P1:5RΔ1005) by homologous recombination, and the recombinant phages were purified as previously described (32). The isolates were introduced by infection into test cells containing plasmids supplying the P1, P7, or pMT1 Par proteins as previously described (32). They replicate as low-copy-number plasmids driven by the P1 replicon. The maintenance stability of the λ-miniP1 parS-containing plasmid was measured after 25 generations of growth of the cells without selection, scoring for the ability of the supF marker that it carries to suppress the lacZ amber mutation in the strain and hence give a red colony on lactose MacConkey indicator plates (24).

Incompatibility tests.

Determination of the ability of supernumerary parS sites to exert incompatibility against the maintenance of plasmids that are making use of a par system was carried out as follows. Colony color partition tests were carried out as described above, except that each strain carried an additional plasmid derived from the vector pACYC184 that carried the parS site from P7 (pALA1850), P1 (pALA1849), or pMT1 (pALA1851). Retention of the pACYC184 derivatives throughout the growth of the strains in liquid medium was ensured by adding 5 μg of tetracycline per ml.

Plasmid silencing assays.

Strain CC2056 was transformed with pBR322 derivatives expressing the P7 (pALA1414), P1 (pALA1413), or pMT1 (pALA1846) Par proteins. Derivatives of pGB2 were constructed which carry the parS region of P7, P1, or pMT1 in the same position in the plasmid and were introduced into these strains by transformation. Silencing of the pGB2 parS derivatives in the presence of Par proteins was assayed by measuring the frequency of spectinomycin-resistant colonies produced on the transformation plates compared to the frequency produced by transformation with the pGB2 vector.

RESULTS

The pMT1par operon.

The pMT1parA and -parB open reading frames (15, 17) are very similar to their P7 counterparts (19). They show 90.5 and 67.3% amino acid identity to P7 ParA and P7 ParB, respectively, whereas the percentages of identity to the P1 equivalents are 57.4 and 47.4%, respectively. The last pMT1 parA codon overlaps the start codon for parB by 1 bp— a feature also seen in the P7 par operon. By comparison with the P7 sequence, it would seem likely that translation of pMT1parA begins at the third methionine: the 22nd amino acid in the open reading frame (Fig. 1B). In this case, the putative ParA protein would consist of 401 amino acids and the ParB protein would consist of 333 amino acids. However, it is also possible that the translation start point is at the first AUG after the putative promoter, which would give a 10-amino-acid amino-terminal extension relative to P7 ParA (Fig. 1B). There are no good matches to the consensus for ribosome binding sites (29) upstream of either potential start point. However, the known P7parA ribosome binding site is not a good match to the consensus either (14).

The likely promoter for the pMT1par operon is evident from its close similarity to the known P7 promoter (Fig. 1B). With these promoter sequences aligned, it is clear that the pMT1 sequence has considerable sequence identity to the region upstream of the P7parA promoter (Fig. 1B). This P7 region acts as an operator sequence and binds ParA to effect autoregulation of the operon (Fig. 1). The presence of common sequences within this region suggests that the pMT1 promoter is also autoregulated. The presence of the sequence TACGT(N)CAATAATT in the same relative position in P7 and pMT1 suggests that this may be responsible for ParA recognition (Fig. 1B). This is consistent with the region protected by ParA binding and with deletion analysis of the P7 operator that placed the left boundary of the operator between bp −74 and −61 relative to the transcription start point (14) (Fig. 1). Other pMT1 sequences to the right of this homology are similar to those of P7. These sequences may also be involved in operator function, because the P7 ParA footprint extends through these bases (Fig. 1B). The presence of three imperfect repeats in the P7 ParA operator region may not be important, because they are not well conserved in the pMT1 sequence (Fig. 1B).

The pMT1par system is fully functional in E. coli and shows unique specificity.

The colony color partition assay was used to determine the activity of the pMT1par region in E. coli. In this assay, the maintenance stability of a λ-miniP1 plasmid carrying a parS partition site is tested when Par proteins are supplied in trans from a pBR322 plasmid carrying the par operon (24). The putative pMT1parS site (Fig. 1C) and par operon were separately amplified by PCR using primers that introduced suitable restriction sites at the end of the pMT1 sequences. The parS site and par operon were then introduced into the λ-miniP1 and pBR322 plasmid vectors, respectively, as described in Materials and Methods. Table 1 shows that the λ-miniP1pMT1parS plasmid was stably maintained only when the pMT1 Par proteins were supplied. This effect was dependent on the presence of the pMT1parS site in the target plasmid, and the degree of stabilization was comparable with that obtained with the P7 or P1par systems (Table 1). Thus, the pMT1par system is fully functional in E. coli as judged by this assay.

TABLE 1.

Results of colony color partition assaysa

| Plasmid carrying par operon | par operon | Test plasmid with parS siteb | % Retention (25 generations) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pBR322 | None | pMT1 | <1 |

| pALA1846 | pMT1parA-parB | pMT1 | 98 |

| pALA1846 | pMT1parA-parB | pMT1 | 93c |

| pALA1414 | P7parA-parB | pMT1 | <1 |

| pALA1413 | P1parA-parB | pMT1 | <1 |

| pALA1846 | pMT1parA-parB | P7 | <1 |

| pALA1414 | P7parA-parB | P7 | 99 |

| pALA1413 | P1parA-parB | P7 | <1 |

| pALA1846 | pMT1parA-parB | P1 | 2 |

| pALA1414 | P7parA-parB | P1 | 2 |

| pALA1413 | P1parA-parB | P1 | 92 |

Retention of a test plasmid carrying the appropriate parS site was measured when a second plasmid supplying the Par proteins from the appropriate par operon was present.

The test plasmids were λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1847 (pMT1parS), λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1993 (P7parS), and λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1952 (P1parS).

λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1843 (190-bp pMT1parS fragment) was used in this test.

The colony color partition assay provides an easy means of mixing and matching different sets of Par proteins and partition sites, because these components are presented on two different plasmids. Table 1 shows that the specificity with which the pMT1 Par proteins recognize the pMT1parS site is unique; neither the P7 Par nor P1 Par proteins can support partition via pMT1parS, and the pMT1 Par proteins cannot support partition via the P7parS or P1parS sites.

The pMT1parS site exerts a unique incompatibility specificity.

Supernumerary P7parS sites exert incompatibility against plasmids partitioned by the P7par region, as do P1parS sites against plasmids supported by the P1par region (13). The pMT1parS site was inserted into a pACYC184 vector (see Materials and Methods), and the resulting plasmid was introduced into the strain used for the colony color partition assay. As shown in Table 2, extra pMT1parS sites destabilized the plasmid being maintained by pMT1par. Thus pMT1parS exerts an incompatibility effect similar to that exerted by P7 or P1parS sites against their respective par systems. Table 2 also shows that the specificity of this pMT1 incompatibility is unique: neither P7parS nor P1parS can exert incompatibility toward pMT1par, and the pMT1parS site did not exert incompatibility toward P7par or P1par.

TABLE 2.

Results of incompatibility assaysa

| parS site on target plasmid | Par protein supplied | parS site carried by pACYC184 derivative | % Retention of target plasmid (25 generations) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P7 | P7 | P7 | 3 |

| P1 | P1 | P1 | 1.5 |

| pMT1 | pMT1 | pMT1 | 1.5 |

| P1 | P1 | pMT1 | 90 |

| P7 | P7 | pMT1 | 94 |

| pMT1 | pMT1 | P7 | 93 |

| pMT1 | pMT1 | P1 | 91 |

| P1 | P1 | P7 | 90 |

| P7 | P7 | P1 | 94 |

The target plasmids were λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1993 (P7parS), λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1952 (P1parS), and λ-P1:5RΔ1005::pALA1843 (pMT1parS). The Par proteins were supplied from pALA1414 (P7 ParA and ParB), pALA1413 (P1 ParA and ParB), and pALA1846 (pMT1 ParA and ParB). Supernumerary parS sites were provided by the presence of the following pACYC184 derivatives: pALA1850 (P7parS), pALA1849 (P1parS), and pALA1851 (pMT1parS). Retention of the target plasmid during approximately 25 generations of unselected growth was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Silencing effects on the establishment of a pGB2 plasmid vector.

Plasmid pGB2 carrying the P1parS site cannot be established in cells expressing the P1 Par proteins, presumably because of the silencing of essential pGB2 genes (18) (Table 3). When this test was repeated with the P7 site and proteins, a similar result was obtained (Table 3). However, an equivalent plasmid carrying the pMT1parS site in the same position and relative orientation to the P1 and P7parS constructs could readily be introduced into cells producing the pMT1 Par proteins (Table 3). This plasmid (pALA1840) was less stably maintained in the presence of its cognate Par proteins than without and was less stably maintained than the pGB2 vector (Table 3). Thus, the pMT1parS site appears to promote a modest silencing effect in this assay, but the effect does not result in a complete block to pGB2 plasmid maintenance and establishment as is the case with the P1parS and P7parS sites.

TABLE 3.

Results of plasmid silencing testsa

| Resident plasmid | Incoming pGB2-based plasmid | Relative transformation efficiencyb |

|---|---|---|

| pALA1846 (pMT1 ParA and ParB) | pALA1840 (pMT1parS) | 0.7c |

| pALA1846 (pMT1 ParA and ParB) | pALA1839 (P7parS) | 1.8 |

| pALA1846 (pMT1 ParA and ParB) | pALA1838 (P1parS) | 2.9 |

| pALA1414 (P7 ParA and ParB) | pALA1840 (pMT1parS) | 1.0 |

| pALA1414 (P7 ParA and ParB) | pALA1839 (P7parS) | <0.01d |

| pALA1414 (P7 ParA and ParB) | pALA1838 (P1parS) | 1.7 |

| pALA1413 (P1 ParA and ParB) | pALA1840 (pMT1parS) | 1.6 |

| pALA1413 (P1 ParA and ParB) | pALA1839 (P7parS) | 3.0 |

| pALA1413 (P1 ParA and ParB) | pALA1838 (P1parS) | <0.01d |

Cells containing the resident plasmid were transformed with pGB2-based plasmids with the parS site inserted in the pGB2 polylinker site.

The values obtained were normalized to the value obtained when the strain was transformed with the pGB2 vector. pGB2 DNA at 0.5 ng gave rise to ca. 500 transformants in each of the three strains.

The plasmid in this strain was lost at a rate of approximately 3% per generation during unselected growth, whereas the pGB2 vector showed no loss in the equivalent strain.

Small colonies were obtained at a relative frequency of 0.01 on the transformation plates, but these were inviable when restreaked on the same medium.

DISCUSSION

The pMT1par locus encodes a partition system that is fully functional in E. coli. It is a member of the P1-P7 family of plasmid partition elements and is very closely related to the P7 element in sequence. It is probable that the locus is important for the maintenance of pMT1, and therefore virulence, in Y. pestis. The 70-kb plasmid pCD1, also present in this species, has another putative partition system—in this case, one that is related to the sop partition system of the F plasmid (15). By employing partition systems of different generic types, the two plasmids presumably avoid interfering with each other by partition-mediated incompatibility.

Partition is likely to involve pairing of daughter plasmids and the subsequent segregation of the paired copies to opposite halves of the dividing cell (23). Inappropriate pairing of two different plasmids that have the same or similar parS sites is the likely source of partition-mediated incompatibility, because it would lead to plasmid missegregation (2). Pairing presumably involves self-recognition of the Par proteins in the partition site complex, as has been demonstrated for the R1 partition system (16). By altering the partition site and the specificity of the Par proteins that it recognizes, one plasmid can avoid pairing with its relative and avoid this source of incompatibility. In order for two plasmids to be compatible with each other, it is important that the parS sites do not recognize the Par proteins of the other species. The results presented here demonstrate that even closely related partition systems can acquire the necessary specificity differences to avoid exerting incompatibility against each other. P7par and pMT1par display different specificities for the recognition of the Par proteins by their respective parS sites, and as a consequence, the parS sites fail to exert partition-mediated incompatibility against the function of the related par systems.

The specificity difference allowing the P1 and P7 partition sites to recognize only their own cognate Par proteins resides in remarkably few critical differences in the parS sequences. The change of a total of 5 bases within the parS discriminator boxes B1 and B2 is sufficient to switch a P7par site to P1 specificity or vice versa (12) (Fig. 1). The pMT1parS site has perfect repeats corresponding to the discriminator boxes of P1 and P7, which differ in sequence from both the P7 and P1 types (Fig. 1). We are currently trying to determine whether the pMT1 discriminator boxes play an equivalent crucial role in defining pMT1 par specificity.

We have demonstrated that three highly related partition systems each exert a different incompatibility specificity. This illustrates the limitations of using incompatibility to predict relatedness. It is probable that the development of unique incompatibility specificity is frequently selected in nature because it facilitates the coexistence rather than competition of diverging plasmid species.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the expert assistance of Marilyn Powers for the operation of the automated sequencing machine.

The portion of this work undertaken at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract number W-7405-ENG-48.

REFERENCES

- 1.Austin S, Hart F, Abeles A, Sternberg N. Genetic and physical map of a P1 miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:63–71. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.1.63-71.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin S J, Nordstrom K. Partition-mediated incompatibility of bacterial plasmids. Cell. 1990;60:351–354. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90584-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolivar F, Rodriguez R L, Green P J, Betlach M D, Boyer H W, Crosa J H, Falkow S. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene. 1977;2:95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouet J Y, Funnell B E. P1 ParA interacts with the P1 partition complex at parS and an ATP-ADP switch controls ParA activities. EMBO J. 1999;18:1415–1424. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Churchward G, Belin D, Nagamine Y. A pSC101-derived plasmid which shows no sequence homology to other commonly used cloning vectors. Gene. 1984;31:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis M A, Austin S J. Recognition of the P1 plasmid centromere analog involves binding of the ParB protein and is modified by a specific host factor. EMBO J. 1988;7:1881–1888. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis M A, Martin K A, Austin S J. Biochemical activities of the ParA partition protein of the P1 plasmid. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1141–1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferber D M, Brubaker R R. Plasmids in Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:839–841. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.2.839-841.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funnell B E. Participation of Escherichia coli integration host factor in the P1 plasmid partition system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6657–6661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funnell B E, Gagnier L. The P1 plasmid partition complex at parS. II. Analysis of ParB protein binding activity and specificity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3616–3624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes F, Austin S J. Specificity determinants of the P1 and P7 plasmid centromere analogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9228–9232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes F, Davis M A, Austin S J. Fine-structure analysis of the P7 plasmid partition site. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3443–3451. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3443-3451.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes F, Radnedge L, Davis M A, Austin S J. The homologous operons for P1 and P7 plasmid partition are autoregulated from dissimilar operator sites. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:249–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu P, Elliott J, McCready P, Skowronski E, Garnes J, Kobayashi A, Brubaker R R, Garcia E. Structural organization of virulence-associated plasmids of Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5192–5202. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5192-5202.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen R B, Lurz R, Gerdes K. Mechanism of DNA segregation in prokaryotes: replicon pairing by parC of plasmid R1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8550–8555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindler L E, Plano G V, Burland V, Mayhew G F, Blattner F R. Complete DNA sequence and detailed analysis of the Yersinia pestis KIM5 plasmid encoding murine toxin and capsular antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5731–5742. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5731-5742.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lobocka M, Yarmolinsky M. P1 plasmid partition: a mutational analysis of ParB. J Mol Biol. 1996;259:366–382. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludtke D N, Eichorn B G, Austin S J. Plasmid-partition functions of the P7 prophage. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:393–406. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch A S, Wang J C. SopB protein-mediated silencing of genes linked to the sopC locus of Escherichia coli F plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1896–1900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin K A, Friedman S A, Austin S J. Partition site of the P1 plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8544–8547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori H, Kondo A, Ohshima A, Ogura T, Hiraga S. Structure and function of the F plasmid genes essential for partitioning. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordstrom K, Austin S J. Mechanisms that contribute to the stable segregation of plasmids. Annu Rev Genet. 1989;23:37–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.23.120189.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radnedge L, Davis M A, Austin S J. P1 and P7 plasmid partition: ParB protein bound to its partition site makes a separate discriminator contact with the DNA that determines species specificity. EMBO J. 1996;15:1155–1162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radnedge L, Youngren B, Davis M, Austin S. Probing the structure of complex macromolecular interactions by homolog specificity scanning: the P1 and P7 plasmid partition systems. EMBO J. 1998;17:6076–6085. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.20.6076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodionov O, Lobocka M, Yarmolinsky M. Silencing of genes flanking the P1 plasmid centromere. Science. 1999;283:546–549. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharpe M E, Errington J. Upheaval in the bacterial nucleoid. An active chromosome segregation mechanism. Trends Genet. 1999;15:70–74. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01660-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shine J, Dalgarno L. The 3′-terminal sequence of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA: complementarity to nonsense triplets and ribosomal binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1342–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sternberg N, Austin S. Isolation and characterization of P1 minireplicons, λ-P1:5R and λ-P1:5L. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:800–812. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.2.800-812.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welkos S L, Davis K M, Pitt L M, Worsham P L, Freidlander A M. Studies on the contribution of the F1 capsule-associated plasmid pFra to the virulence of Yersinia pestis. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1995;13:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Youngren B, Austin S. Altered ParA partition proteins of plasmid P1 act via the partition site to block plasmid propagation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1023–1030. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4761842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]