Abstract

A cyclic version of the Entner-Doudoroff pathway is used by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to metabolize carbohydrates. Genes encoding the enzymes that catabolize intracellular glucose to pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate are coordinately regulated, clustered at 39 min on the chromosome, and collectively form the hex regulon. Within the hex cluster is an open reading frame (ORF) with homology to the devB/SOL family of unidentified proteins. This ORF encodes a protein of either 243 or 238 amino acids; it overlaps the 5′ end of zwf (encodes glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) and is followed immediately by eda (encodes the Entner-Doudoroff aldolase). The devB/SOL homolog was inactivated in P. aeruginosa PAO1 by recombination with a suicide plasmid containing an interrupted copy of the gene, creating mutant strain PAO8029. PAO8029 grows at 9% of the wild-type rate using mannitol as the carbon source and at 50% of the wild-type rate using gluconate as the carbon source. Cell extracts of PAO8029 were specifically deficient in 6-phosphogluconolactonase (Pgl) activity. The cloned devB/SOL homolog complemented PAO8029 to restore normal growth on mannitol and gluconate and restored Pgl activity. Hence, we have identified this gene as pgl and propose that the devB/SOL family members encode 6-phosphogluconolactonases. Interestingly, three eukaryotic glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) isozymes, from human, rabbit, and Plasmodium falciparum, contain Pgl domains, suggesting that the sequential reactions of G6PDH and Pgl are incorporated in a single protein. 6-Phosphogluconolactonase activity is induced in P. aeruginosa PAO1 by growth on mannitol and repressed by growth on succinate, and it is expressed constitutively in P. aeruginosa PAO8026 (hexR). Taken together, these results establish that Pgl is an essential enzyme of the cyclic Entner-Doudoroff pathway encoded by pgl, a structural gene of the hex regulon.

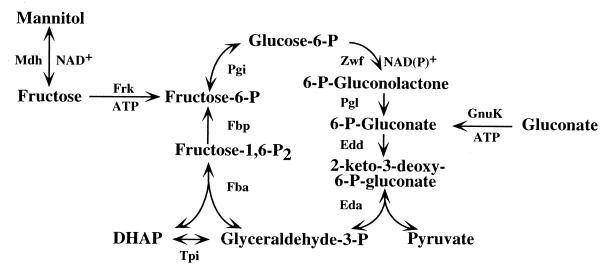

A cyclic version of the Entner-Doudoroff pathway is used by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to metabolize carbohydrates (Fig. 1) (9, 19, 36). The members of the pathway that are responsible for the metabolism of glucose to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and pyruvate are coordinately regulated and induced by growth on glycerol, fructose, mannitol, glucose, and gluconate. They are clustered in at least three operons near 39 min on the chromosome and are referred to as the hex regulon. They are under the control of the recently identified repressor hexR (29; W. D. Proctor, P. W. Hager, and P. V. Phibbs, Jr., Abstr. 98th Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1998, abstr. K-135).

FIG. 1.

Cyclic Entner-Doudoroff pathway of P. aeruginosa. In this pathway, the catabolism of mannitol occurs via glucose-6-phosphate and requires the activity of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zwf, EC 1.1.1.49), while the catabolism of gluconate does not require Zwf. Additional enzymatic activities are abbreviated as follows: Eda, 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate aldolase (EC 4.1.2.14); Edd, 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase (EC 4.2.1.12); Fbp, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (EC 3.1.3.11); Fba, fructose bisphosphate aldolase (EC 4.1.2.13); Frk, fructokinase (EC 2.7.1.4); GnuK, gluconokinase (EC 2.7.1.12); Mdh, mannitol dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.67); Pgi, phosphoglucoisomerase (EC 5.3.1.9); Pgl, 6-phosphogluconolactonase (EC 3.1.1.31); Tpi, triose phosphate isomerase (EC 5.3.1.1).

The DNA sequence of the P. aeruginosa zwf gene encoding the unique glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase of P. aeruginosa was recently reported (22). Zwf catalyzes the oxidation of glucose-6-phosphate to 6-phosphogluconolactone using either NAD or NADP as a cofactor. While 6-phosphogluconolactone can be hydrolyzed nonenzymatically to 6-phosphogluconate, the enzymatic activity (EC 3.1.1.31) was described some time ago (6). A phosphogluconolactonase activity has been identified and partially purified from Pseudomonas fluorescens (16) but, to our knowledge, has not been identified in P. aeruginosa. Purification of 6-phosphogluconolactonase has been achieved from Zymomonas mobilis (33), bovine erythrocytes (3), and bass liver (26), and in each case the enzyme appears to be a monomer of 26 to 30 kDa. Escherichia coli contains a 6-phosphogluconolactonase which is necessary for optimal growth when using the pentose phosphate shunt. Hence, pgi pgl double mutants, which cannot convert glucose-6-phosphate to fructose-6-phosphate, grow very slowly on glucose (18). The pgl gene locus was tightly linked by transductional analysis to att-λ, located at 15 min on the E. coli K-10 chromosome (17).

The isolation and molecular characterization of a pgl structural gene were first reported only recently (GenBank accession no. AF029673) (P. W. Hager, M. W. Calfee, and P. V. Phibbs, Abstr. 99th Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1999, abstr. K-148). An open reading frame with homology to devB, a putative “developmentally regulated” glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, was identified immediately downstream of the P. aeruginosa Zwf coding sequence. Insertional inactivation of that devB homolog resulted in a slow-growth phenotype on mannitol and the loss of 6-phosphogluconolactonase activity. Normal growth on mannitol and 6-phosphogluconolactonase activity were restored by a plasmid containing the subcloned open reading frame, identifying the P. aeruginosa devB homolog as pgl. The expression of Pgl activity was positively regulated by growth on carbohydrates and negatively regulated by growth on succinate, a phenotype that is consistent with this gene's being a member of the hex regulon. Subsequently, a human cDNA with homology to the P. aeruginosa pgl and other devB homologs was reported to encode Pgl (8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmida | Relevant characteristicsb | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||

| PAO1 | Prototroph | Hollowayc (13) |

| PAO1838 | eda-9001 met-9020 | Matsumotod (31) |

| PAO8029 | pgl::aacC1 | This study |

| PAO8033 | aacC1, Cbr | This study |

| PAO9010 | zwf::aacC1 | 22 |

| PAO8026 | hexR::aacC1 | 29 |

| E. coli DH5α | F− φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Clonetech |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-3Zf(+) | Apr, cloning vector | Promega |

| pGEM-7Zf(+) | Apr, cloning vector | Promega |

| pTZ19R | Apr, cloning vector | PL-Pharmacia |

| pUCGM | Apr, aacC1 | Hassette (32) |

| pUCP18 | Cbr, oriV | 37 |

| pUCP22 | Cbr, oriV | 37 |

| pPZ149 | 1.2-kb BamHI fragment from pPZ300 in pTZ19R | This study |

| pPZ300 | zwf pgl eda Cbr oriV | 34 |

| pPZ303 | zwf pgl eda Cbr oriV | 34 |

| pPZ375 | Cbr oriV | 35 |

| pPZ474 | 2.9-kb BamHI fragment from pPZ300 in pGEM-3Zf(+), eda | This study |

| pPZ475 | Opposite orientation of 2.9-kb BamHI fragment in pGEM-3Zf(+), eda | This study |

| pPZ502 | 1.1-kb PstI-BamHI fragment from pPZ505 in pUCP18, eda oriV | This study |

| pPZ505 | PstI deletion of pPZ475, eda | This study |

| pPZ524 | 2.4-kb SstII fragment, zwf, in pUCP22 | This study |

| pPZ571 | 1.1-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pPZ502 in pPZ375, eda oriV | This study |

| pPZ594 | 2-kb XhoI-ApaI from pPZ303 in pGEM-7Zf(+), pgl | This study |

| pPZ595 | EcoRI-SacI deletion of pPZ594, creates unique BamHI site in pgl | This study |

| pPZ596 | 0.86-kb aacC1 cassette from pUCGM inserted into BamHI site of pPZ595 | This study |

| pPZ602 | Identical to pPZ596 except aacC1 cassette reversed | This study |

| pPZ603 | 2-kb SalI-EcoRI from pPZ594 in pUCP18, pgl oriV | This study |

P. aeruginosa gene designations are according to Holloway et al. (14)

Abbreviations: Cbr, carbenicillin resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance; aacC1, gentamicin resistance cassette.

B. W. Holloway, Monash University, Australia.

H. Matsumoto, Shinshu University, Matsumoto, Japan.

D. Hassett, University of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Genetic techniques.

The eda gene was subcloned from plasmid pPZ300 in two steps. First, both orientations of a 2.9-kb BamHI fragment from pPZ300 were cloned into pGEM-3Zf(+), creating pPZ474 and pPZ475. Second, a PstI deletion of pPZ475 (removing 1.8 kb) resulted in pPZ505. The remaining 1.1-kb fragment containing eda from pPZ475 was cut out with PstI and BamHI and ligated into the Pseudomonas-compatible vector pUCP18, creating pPZ502, in which the eda gene is in the sense orientation following the lac promoter. The antisense orientation of the eda gene relative to the lac promoter was created by moving the 1.1-kb eda fragment into the Pseudomonas-compatible vector pPZ375, creating pPZ571.

The pgl knockout strain PAO8029 and the pgl merodiploid PAO8033 were constructed as follows. The 2-kb XhoI-ApaI fragment from plasmid pPZ303, containing the pgl gene, was cloned into the XhoI site of pGEM-7Z(+), creating pPZ594. The BamHI site within the polylinker of pPZ594 was removed by digestion of pPZ594 with EcoRI and SacI with ligation of the product, creating pPZ595. The 0.9-kb SmaI fragment containing the gentamicin resistance cassette (aacC1) from pUCGM (32) was then cloned into the single remaining BamHI site of pPZ595 (after making the BamHI ends flush with T4 DNA polymerase), resulting in a disruption of the pgl coding sequence. Both orientations of aacC1 into pgl were obtained as plasmids pPZ596 and pPZ602. DNA from pPZ596 or pPZ602 was electroporated into P. aeruginosa PAO1 using the method of Enderle and Farwell (11). Three putative recombinants were isolated on L agar containing gentamicin. The characterization of two of these mutants as PAO8029 and PAO8033 is described in the Results section.

Southern blots.

Genomic DNA was isolated from strains PAO1, PAO8029, and PAO8033 using hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) followed by equilibrium centrifugation in a CsCl gradient (2). The genomic DNA was digested with BamHI, and 1 μg of each digest was loaded on a 1% agarose gel, electrophoresed, and transferred to a nylon membrane by capillary action (2). Digestion of pPZ595 with ApaI and XhoI yielded DNA fragments of 2 and 3 kb, representing the pgl gene and the vector, respectively. The fragments were isolated from a 1% agarose gel using Qiaex resin (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.) and labeled with [α-32P]dATP using the RadPrime DNA labeling system (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) as described by the manufacturers. Duplicate blots were probed with approximately 107 cpm of either the pgl or the vector-derived probe, washed, and exposed to X-ray film for 24 to 48 h.

Preparation of 6-phosphogluconolactone and assays of 6-phosphogluconolactonase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity.

A qualitative assay of 6-phosphogluconolactonase, including the preparation of 6-phosphogluconolactone (by lyophilization of 6-phosphogluconate) and its quantitation using hydroxylamine and ferric chloride, has been previously described (17). The extinction coefficient of the ferric hydroxymate of 6-phosphogluconolactone was assumed to be equal to that determined for δ-gluconolactone (E530 = 580 M−1). For the determination of the specific activity of 6-phosphogluconolactonase, a method based on that of Beutler et al. was employed (4). Briefly, the production of 6-phosphogluconate was followed using 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase. Assays were done at 28°C in 0.1 M Tris-Cl buffer (pH 7.5) with 0.3 mM NADP, 0.1 mM 6-phosphogluconolactone, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 U of yeast 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase assays were done at 28°C; otherwise, the assay was as previously described (15). For the preparation of extracts for enzymatic assays, cells were harvested in mid-log-phase growth following growth in minimal medium (21) with a carbon source. Cells were washed with cold 0.9% NaCl, and the cell pellets were suspended in 5% of the original culture volume of 50 mM Tris-Cl–1 mM EDTA–1 mM dithiothreitol (pH 8) and broken in a French press at 16,000 lb/in2. Extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 175,000 × g for 30 min (Sorvall T-1270, 45,000 rpm). Protein was measured by the method of Bradford (5) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Chemicals and coupling enzymes were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.), and Bradford reagent was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.).

Growth rates.

Strains were initially isolated on selective Luria-Bertani agar plates and subsequently grown overnight in liquid minimal medium containing 10 mM succinate. Fresh minimal medium cultures containing 2 mM succinate and 20 mM gluconate or 2 mM succinate and 20 mM mannitol were started with a 10% (vol/vol) inoculum from the overnight culture. For the determination of growth rates, the turbidity was measured with a Klett-Summerson colorimeter with a red no. 66 filter. Under these conditions, P. aeruginosa utilizes the available succinate for growth before shifting to metabolism of the gluconate or mannitol (23). Hence, the gluconate- and mannitol-dependent growth rates were determined from the second phase of the growth curves.

DNA sequencing.

The DNA sequences of the cloned fragments in pPZ505, pPZ149, and pPZ595 were determined by Commonwealth Biotechnologies, Inc. (Richmond, Va.). Plasmid pPZ149 contains a 1.2-kb BamHI fragment derived from pPZ300 cloned into pTZ19R.

Computer analysis of sequences.

Comparisons between individual sequences were carried out using the Genetics Computer Group software analysis package (Madison, Wis.), while comparisons to databases were carried out using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) network service at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), National Institutes of Health (1). Searches for promoter sequences were carried out using the program NNPP (www-hgc.lbl.gov/projects/promoter.html) (30).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequences of the pgl and eda genes were updated in GenBank (accession no. AF029673, 2 April 1999).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Nucleotide sequence encoding eda and pgl/devB.

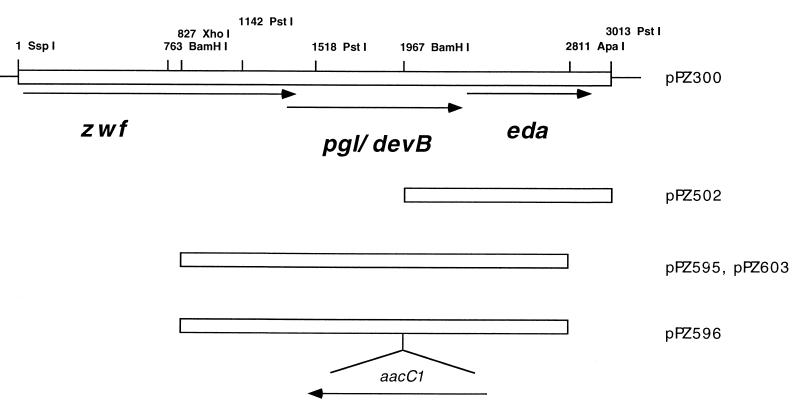

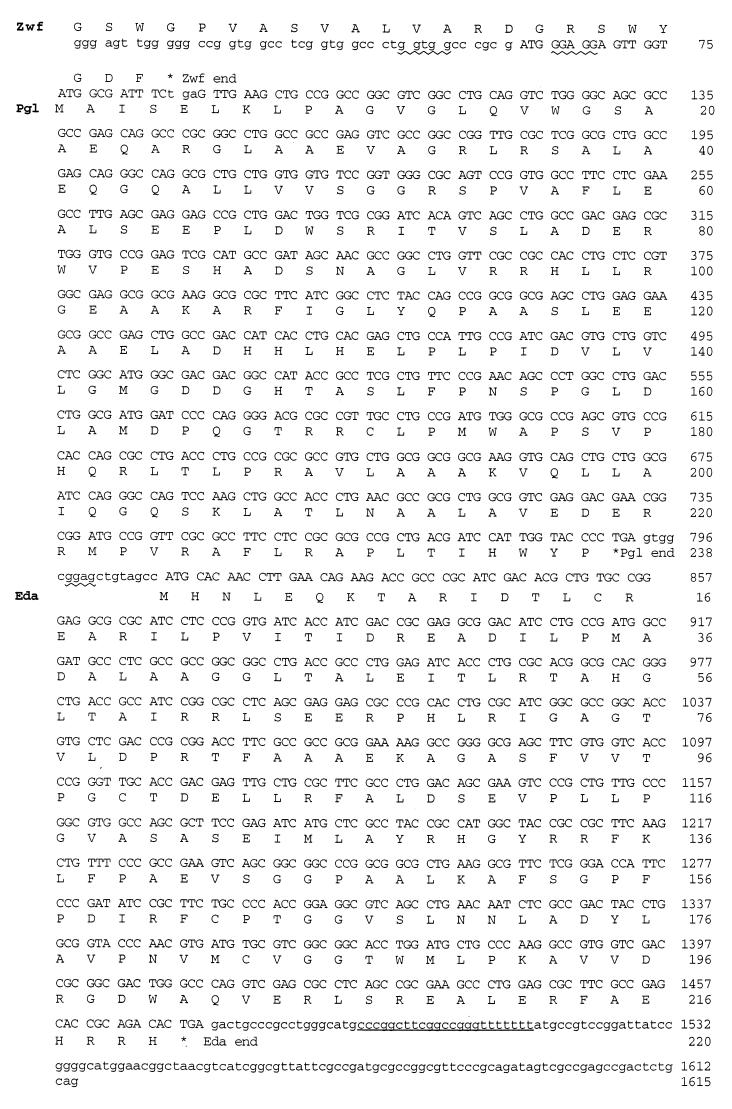

The cloning and DNA sequence of the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (zwf) of P. aeruginosa were reported recently (22). Continuing downstream from zwf, two additional open reading frames were found (summarized in Fig. 2). Earlier work established that the Entner-Doudoroff aldolase gene (eda) was closely linked to zwf (10, 31), and both genes were subsequently cloned on an 11-kb fragment of P. aeruginosa DNA (34). The smallest subclones able to complement the eda mutant PAO1838 for growth on mannitol, glucose, and gluconate contained the two orientations of a 1.1-kb BamHI-PstI DNA fragment 3′ to zwf (in plasmids pPZ502 and pPZ571). The DNA sequence of this region showed the eda gene to be 723 bp downstream of and in the same orientation as zwf (Fig. 3). The DNA sequence predicts that Eda contains 220 amino acids sharing 42% identity with its E. coli homolog. It is preceded by a Shine-Dalgarno sequence (GGAG) and followed by a potential transcription terminator. Although a promoter sequence between zwf and eda has not been identified, we presume that the 1.1-kb eda fragment does contains a promoter, since both orientations of the cloned eda gene are able to complement PAO1838.

FIG. 2.

Summary of the organization of the zwf, pgl, and eda genes and plasmids derived from pPZ300. Plasmid pPZ300 contains 11 kb of PAO1-derived DNA, of which only 3 kb is indicated here. Plasmid pPZ502 complements the eda mutant PAO1838. It was constructed by subcloning a 1-kb BamHI-PstI fragment from pPZ505 into the broad-host-range vector pUCP18. pPZ595 and pPZ603 contain the same 2-kb XhoI-SalI fragment, and pPZ603 complements the pgl mutant PAO8029. pPZ596 is a Pseudomonas suicide vector, constructed from pPZ595. It contains a gentamicin resistance cassette, aacC1, inserted into the BamHI site within pgl/devB. pPZ602 (not shown) is identical to pPZ596 except for the orientation of the aacC1 cassette.

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the pgl and eda genes. The coding sequence of Pgl begins within the 3′ end of the Zwf coding sequence at nucleotide 76. There is an alternative initiation codon for Pgl at nucleotide 61 (indicated in upper case). The coding sequence for Eda is separated from the end of Pgl by only 17 bp. Indicated are potential Shine-Dalgarno (wavy underlining) and rho-independent transcriptional termination sequences (underlined).

The 723-bp region between zwf and eda has one open reading frame in the same orientation as Zwf and Eda with two potential ATG start codons located within the last eight codons of the Zwf sequence (Fig. 2). The potential initiation codons are in frame with each other, separated by only 5 codons, and both have potential Shine-Dalgarno sequences (GGUGG and GGAGG). The second initiation codon appears to be the true start site, as a P. aeruginosa-derived protein with the predicted N-terminal amino acid sequence (AISELKLPAGVGLQV) has been identified (Dennis Ohman, personal communication). This open reading frame encoding 238 amino acids has similarity to devB (from Anabaena) and SOL (from Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (see below). DevB has been proposed to be a “developmentally regulated” glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (GenBank accession no. U14553). While P. fluorescens and Pseudomonas cepacia (reclassified as Burkholderia cepacia) have two glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases that function with either NAD+ (in a catabolic role) or NADP+ (in an anabolic role) (7, 20, 25), it is clear that P. aeruginosa has a single glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity (Zwf) capable of using either NAD+ or NADP+ (22, 28). One interpretation consistent with a single zwf gene is that the open reading frame with homology to devB/SOL represents a 6-phosphogluconolactonase.

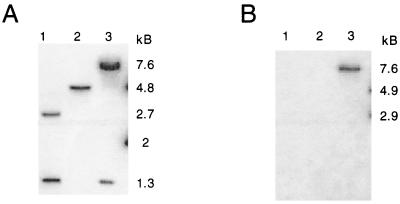

To test this hypothesis, the devB open reading frame was interrupted by insertion of the aacC1 gentamicin resistance cassette at the BamHI site. The related suicide plasmids pPZ596 and pPZ602 contain the two orientations of aacC1 (Fig. 2). After electroporation of pPZ596 and pPZ602 into P. aeruginosa PAO1, three gentamicin-resistant colonies were isolated. Two of these strains were gentamicin resistant but carbenicillin sensitive, suggesting gene replacement by recombination of the plasmid into the chromosome via double crossovers. One of these isolates was named PAO8029 and studied further. The third isolate, PAO8033, had both carbenicillin and gentamicin resistance, suggesting recombination via a single crossover. Southern blot analysis of BamHI-digested DNA isolated from PAO1, PAO8029, and PAO8033 showed that these interpretations were correct (Fig. 4). BamHI-digested PAO1 DNA contains two fragments (1.3 and 2.7 kb) that hybridized to the devB-derived probe. For PAO8029, the BamHI site within the devB gene has been replaced with the 0.8-kb aacC1 cassette, resulting in a single band of 4.8 kb. For PAO8033 there are two bands that hybridized to the devB probe, 1.3 kb and 7.7 kb (Fig. 4A). When a duplicate blot was probed with DNA derived from the plasmid vector, only PAO8033 and the plasmid controls showed hybridization (Fig. 4B). Hence, for PAO8033, the results were consistent with a single crossover of the plasmid into the amino-terminal side of the gene.

FIG. 4.

Southern blots of genomic DNA digested with BamHI. Duplicate blots were prepared as follows: lane 1, PAO1-derived DNA; lane 2, PAO8026-derived DNA; lane 3, PAO8033-derived DNA. (A) Blot hybridized with pgl-specific probe. (B) Blot hybridized with plasmid vector-specific probe.

Identification of devB as pg1.

In P. aeruginosa, Zwf activity is absolutely required for growth on mannitol but not for growth on gluconate (Fig. 1). Compared to PAO1, PAO8029 grew at a reduced rate on gluconate (50%), as did the zwf mutant strain PAO9010 (82%). However, PAO8029 grew very slowly on mannitol, with a doubling time of approximately 30 h, or 9% of the wild-type rate (Table 2). While this is the expected phenotype of a pgl mutant (see below), it could represent a leaky zwf phenotype, so we tested for complementation using various plasmids. The phenotype of very slow growth on mannitol was not complemented by a plasmid vector (pPZ375) or the vector containing zwf (pPZ524) (data not shown), but was complemented by pPZ603 containing the devB homology region (Table 2). This confirmed our supposition that this devB homolog is not a glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; instead, it represents a unique gene.

TABLE 2.

Growth rates of P. aeruginosa strains with either gluconate or mannitol as the carbon sourcea

| Strain/plasmid | Doubling time (h)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Gluconate | Mannitol | |

| PAO1 | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 2.75 ± 0.06 |

| PAO8029 | 1.80 ± 0.02 | 28.4 ± 0.92 |

| PAO8029/pPZ603 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 3.02 ± 0.22 |

| PAO9010 (zwf) | 1.11 ± 0.10 | No growth |

Strains were grown at 37°C in minimal medium containing 2 mM succinate plus either 20 mM gluconate or 20 mM mannitol. Growth rates were determined from the gluconate- or mannitol-dependent phase of growth.

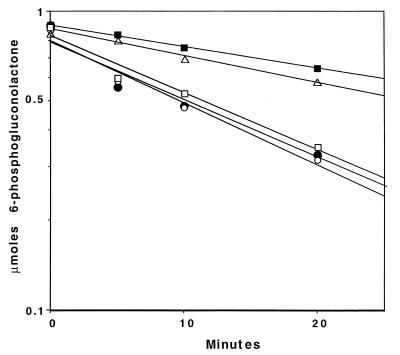

The phenotype of very slow growth on mannitol for PAO8029 is reminiscent of E. coli phosphogluconolactonase mutants (17, 18). Hence, we assayed for 6-phosphogluconolactonase after growing P. aeruginosa PAO1, PAO9010 (zwf), PAO8029, and PAO8029 containing pPZ603 with gluconate as the carbon source. The ferric hydroxymate assay of 6-phosphogluconolactonase activity that measures the disappearance of the substrate is essentially qualitative because of a relatively high nonenzymatic rate and the presence of the γ and δ 6-phosphogluconolactones in the substrate (17). Nevertheless, it is clear from the data in Fig. 5 that extracts from PAO1 and PAO9010 had phosphogluconolactonase activity, while the PAO8029 extract was essentially identical to the control without extract protein. An extract of PAO8029 containing plasmid pPZ603 also had phosphogluconolactonase activity, demonstrating complementation of the gene. Hence, the P. aeruginosa devB homolog was identified as pgl.

FIG. 5.

Extracts of strain PAO8029 lack 6-phosphogluconolactonase. Assays contained 6-phosphogluconolactone and either water (▵) or 100 μg of cell-free extract protein derived from strain PAO1 (□), PAO8029 (■), PAO8029 containing plasmid pPZ603 (●), or PAO9010 (zwf) (○). At the indicated times, the reactions were terminated, and remaining 6-phosphogluconolactone was converted to a ferric hydroxymate and quantified colorimetrically. Strains were grown on minimal medium containing 20 mM gluconate as the sole carbon source, and cell extracts were prepared as described in the text.

Given the nonenzymatic rate of hydrolysis for 6-phosphogluconolactone (with a t1/2 of approximately 50 min; see Fig. 5), the dramatic reduction in growth rate for the pgl mutant strains grown on mannitol might seem surprising. However, this phenotype is consistent with the normally short metabolic lifetime of 6-phosphogluconolactone, as pointed out by Scopes (33). However, this would not account for the reduced rate of growth by strain PAO8029 on gluconate (compared to PAO1 and PAO9010 in Table 2). Since the cyclic Entner-Doudoroff pathway in P. aeruginosa would allow the synthesis of 6-phosphogluconolactone, we suggest that the substrate for Pgl, 6-phosphogluconolactone, is toxic.

It seems essential that there should be similar amounts of 6-phosphogluconolactonase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in the cell in order to maintain a balanced flux through this metabolic pathway. A quantitative assay for 6-phosphogluconolactonase, in which the 6-phosphogluconolactonase is coupled to a 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, showed that there are similar levels of these activities in extracts from PAO1 cells grown on gluconate (353 ± 26 mIU/mg for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 388 ± 41 mIU/mg for 6-phosphogluconolactonase).

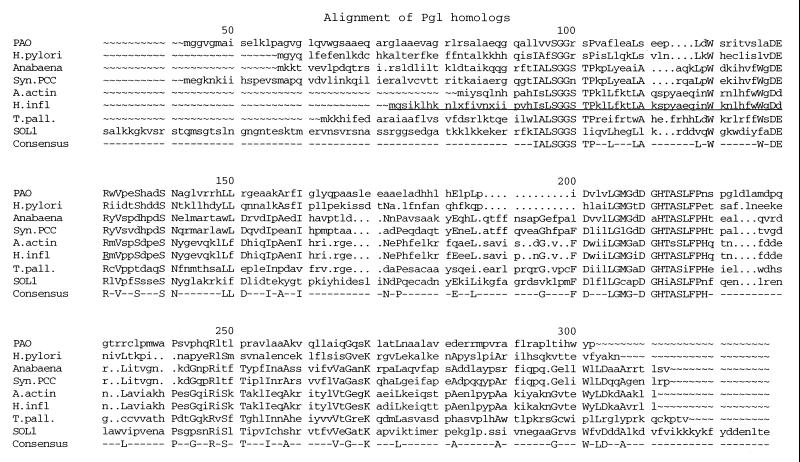

Conservation within the Pgl family.

A search of the NCBI databases using the BLAST program (1) with the deduced amino acid sequence for Pgl as a query turned up a large number of family members, previously identified as DevB or SOL homologs. Alignment of several such members revealed important regions of conservation (motifs) that may include the active-site residues of 6-phosphogluconolactonase (Fig. 6). The two most conserved regions include IALSGGSTP and LGMG-DGHTASLFPH. Note that the genomic sequence of the Haemophilus influenzae 6-phosphogluconolactonase homolog (devB; HIO556) is truncated prior to this first motif (12). However, the upstream sequence of H. influenzae does encode this motif with an appropriate ATG start codon (underlined in Fig. 6), as well as two internal stop codons (indicated as x in Fig. 6). We suggest either that the stop codons are sequencing artifacts or that H. influenzae has a mechanism for translating through them. A cDNA encoding a human cytosolic Pgl has recently been cloned and expressed in E. coli and shown to have Pgl activity (8). In addition to observing its homology with P. aeruginosa Pgl, the bacterial DevB, and the yeast SOL proteins, these authors also identified a less conserved homology with glucosamine-6-phosphate isomerase.

FIG. 6.

Alignment of amino acid sequences for representative homologs of the P. aeruginosa phosphogluconolactonase. The homologs were identified using the BLAST program and were aligned with Genetics Computer Group programs. The consensus sequence was generated using a plurality of five. The sequences include the PAO-derived sequence reported here, and ones from Helicobacter pylori (GenBank accession no. AE000616), Anabaena (Swiss-Prot. accession no. P46016), Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6083 (DDBJ accession no. D90916), Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (DDBJ accession no. D88189), H. influenzae (Swiss-Prot. accession no. Q57039), Treponema pallidum (GenBank accession no. AAC65464), and S. cerevisiae SOL1 (Swiss-Prot. accession no. P50278). Sequence numbers refer to the S. cerevisiae SOL1 amino acid sequence (residues 1 to 30 not shown). Additional N-terminal sequence for the H. influenzae homolog (underlined) was deduced from the DNA sequence (12).

The overlapping nature of Zwf and Pgl in P. aeruginosa suggests a very tight translational control, perhaps necessary to balance their enzymatic activities. In general, the prokaryote-derived members of the pgl family are found next to zwf (24), with the notable exception of E. coli. Since pgl was originally identified and mapped in E. coli K-10 (an HfrC derivative of K-12), we were surprised when searches using BLAST failed to identify an obvious homolog in E. coli. The closest might be nagB (8) (GenBank accession no. M19284), whose map position is 1 min from the E. coli pgl gene.

In general, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases are highly conserved proteins of about 500 amino acids. However, the rabbit microsomal glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, derived from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, contains 763 amino acids, with a “noncatalytic domain” in the middle of the enzyme (27). The “noncatalytic domain” contains the second Pgl motif (residues 399 to 411 of the rabbit microsomal glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase are GMGtDGHTASLFP). Likewise, the amino acid sequence of the unusual glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase of the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, begins with a Pgl domain (33a). The recently described hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from human bone marrow also contains a Pgl domain, located in the carboxy-terminal third of the gene (8, 24). Thus, it appears that these animals have evolved a simple solution for efficient metabolic flux through glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphogluconolactonase by combining both activities into a single protein.

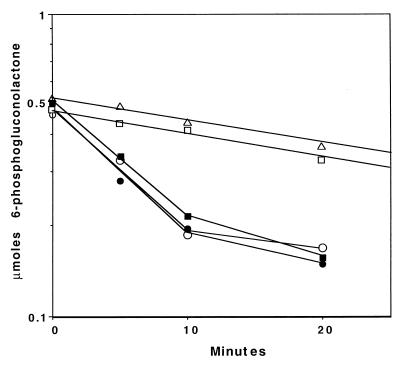

pg1 is a member of the hex regulon.

Since pgl follows zwf directly, both in the arrangement of the genes and in metabolic pathway function, it seemed likely that they would be coordinately regulated. Growth with gluconate as the carbon source induced glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zwf), while growth on succinate did not (340 ± 18 mIU/mg versus 3 ± 3 mIU/mg). Similarly, we observed that PAO1 had 6-phosphogluconolactonase activity when grown on gluconate but not when grown on succinate (Fig. 7). Recently, the repressor for the hex regulon has been identified (29; Procter et al., abstr. K-135). The HexR protein represses the expression of all the enzymes in the hex regulon by binding to DNA sequences upstream of each operon. Inactivation of HexR by insertion of a gentamicin resistance cassette into the chromosomal copy of hexR results in constitutive expression of the hex regulon (29; Procter et al., abstr.). In the hexR mutant strain PAO8026, 6-phosphogluconolactonase activity was present at equivalent levels when the strain was grown on either gluconate or succinate (Fig. 7). Thus, pg1 is under the control of HexR and is demonstrated to be another member of the hex regulon.

FIG. 7.

pg1 is a member of the hex regulon. Assays contained 6-phosphogluconolactone and either water (▵) or 100 μg of cell extract protein derived from strain PAO1 grown with succinate (□) or gluconate (■) as the sole carbon source or PAO8026 (hexR) grown with succinate (○) or gluconate (●) as the sole carbon source. At the indicated times, reactions were terminated, and the remaining 6-phosphogluconolactone was quantified colorimetrically.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ann Covert-Rinaldi for technical assistance and Dan Martin, Jeff Smith, and Dennis Ohman for their critical comments.

This research was supported by the Brody School of Medicine of East Carolina University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, et al. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer H P, Srihari T, Jochims J C, Hofer H W. 6-Phosphogluconolactonase: purification, properties and activities in various tissues. Eur J Biochem. 1983;133:163–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutler E, Kuhl W, Gelbart T. Blood cell phosphogluconolactonase: assay and properties. Br J Haematol. 1986;62:577–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1986.tb02970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodie A F, Lipmann F. Identification of a gluconolactonase. J Biol Chem. 1955;212:677–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacciapuoti A F, Lessie T G. Characterization of the fatty acid-sensitive glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas cepacia. J Bacteriol. 1977;132:555–563. doi: 10.1128/jb.132.2.555-563.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collard F, Collet J, Gerin I, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Van Schaftingen E. Identification of the cDNA encoding human 6-phosphogluconolactonase, the enzyme catalyzing the second step of the pentose phosphate pathway. FEBS Lett. 1999;459:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conway T. The Entner-Duoderoff pathway: history, physiology and molecular biology. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;103:1–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuskey S M, Wolff J A, Phibbs P V, Jr, Olsen R H. Cloning of genes specifying carbohydrate catabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:865–871. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.865-871.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enderle P J, Farwell M A. Electroporation of freshly plated Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells. BioTechniques. 1998;25:954–958. doi: 10.2144/98256bm05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, FitzHugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, Lui L-I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Sprriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holloway B W. Genetics of Pseudomonas. Bacteriol Rev. 1969;33:419–443. doi: 10.1128/br.33.3.419-443.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holloway B W, Romling U, Tummler B. Genomic mapping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Microbiology. 1994;140:2907–2929. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hylemon P B, Phibbs P V., Jr Independent regulation of hexose catabolizing enzymes and glucose transport activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;48:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90813-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwasaki K. Studies on 6-phosphogluconolactonase in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Seikagaku. 1965;37:788–793. . (In Japanese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kupor S R, Fraenkel D G. 6-Phosphogluconolactonase mutants of Escherichia coli and a maltose blue gene. J Bacteriol. 1969;100:1296–1301. doi: 10.1128/jb.100.3.1296-1301.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kupor S R, Fraenkel D G. Glucose metabolism in 6 phosphogluconolactonase mutants of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:1904–1910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lessie T G, Phibbs P V., Jr Alternative pathways of carbohydrate utilization in pseudomonads. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:359–387. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lessmann D, Schimz K L, Kurz G. d-Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Entner-Doudoroff enzyme) from Pseudomonas fluorescens: purification, properties and regulation. Eur J Biochem. 1975;59:545–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch W H, Franklin M. Effect of temperature on diauxic growth with glucose and organic acids in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Arch Microbiol. 1978;118:133–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00415721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma J-F, Hager P W, Howell M L, Phibbs P V, Jr, Hassett D J. Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa zwf gene encoding glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, an enzyme important in resistance to methyl viologen (paraquat) J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1741–1749. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1741-1749.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacGregor C H, Wolff J A, Arora S K, Hylemon P B, Phibbs P V., Jr . Catabolite repression control in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In: Galli E, Silver S, Witholt B, editors. Pseudomonas: molecular biology and biotechnology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason P J, Stevens D, Diez A, Knight S W, Scopes D A, Vulliamy T J. Human hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (glucose 1-dehydrogenase) encoded at 1p36: coding sequence and expression. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1999;25:30–37. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1999.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maurer P, Lessmann D, Kurz G. d-Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases from Pseudomonas fluorescens. Methods Enzymol. 1982;89D:261–270. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)89047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medina-Puerta M M, Gallego-Iniesta M, Garrido-Pertierra A. Purification of 6-phosphogluconolactonase from bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) liver. Biochem Int. 1988;17:1011–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozols J. Isolation and the complete amino acid sequence of lumenal endoplasmic reticulum glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5302–5306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phibbs P V, Jr, McCowen S M, Feary T W, Blevins W T. Mannitol and fructose catabolic pathways of Pseudomonas aeruginosa carbohydrate-negative mutants and pleiotropic effects of certain enzyme deficiencies. J Bacteriol. 1978;133:717–728. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.2.717-728.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Proctor W D. Genetic and biochemical characterization of HexR, a negative regulator of carbohydrate utilization of the hex regulon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Ph.D. dissertation. Greenville, N.C: East Carolina University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reese M G, Harris N L, Eeckman F H. Large scale sequencing specific neural networks for promoter and splice site recognition. In: Hunter L, Klein T E, editors. Biocomputing: Proceedings of the 1996 Pacific Symposium. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roehl R A, Feary T W, Phibbs P V., Jr Clustering of mutations affecting central pathway enzymes of carbohydrate catabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:1123–1129. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.3.1123-1129.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schweizer H P. Small broad-host-range gentamicin resistance cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques. 1993;15:831–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scopes R K. 6-Phosphogluconolactonase from Zymomonas mobilis. FEBS Lett. 1985;193:185–188. [Google Scholar]

- 33a.Shahabuddin M, Rawlings D J, Kaslow D C. A novel glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in Plasmodium falciparum: cDNA and primary protein structure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1219:191–194. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Temple L, Cuskey S M, Perkins R E, Bass R C, Morales N M, Christie G E, Olsen R H, Phibbs P V., Jr Analysis of cloned structural and regulatory genes for carbohydrate utilization in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6396–6402. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6396-6402.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Temple L, Sage A, Christie G E, Phibbs P V., Jr Two genes for carbohydrate catabolism are divergently transcribed from a region of DNA containing the hexC locus in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4700–4709. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4700-4709.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Temple L M, Sage A E, Schweizer H P, Phibbs P V., Jr . Carbohydrate catabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In: Montie T C, editor. Pseudomonas. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 35–72. [Google Scholar]

- 37.West S E H, Schweizer H P, Dall C, Sample A K, Runyen-Janecky L J. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1994;128:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]