Abstract

The current study assesses the extent to which government leaders’ personality traits are related to divergent policy responses during the pandemic. To do so, we use data from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker initiative (OxCGRT) to measure the speed and magnitude of policy responses across countries and NEGex, a dataset that maps the personality traits of current heads of government (presidents or prime ministers) in 61 countries. We find that world leaders scoring high on “plasticity” (extraversion, openness) were quicker to implement travel restrictions and provide financial relief as well as offered a stronger response in general (average overall response). Whereas, leaders scoring high on “stability” (conscientiousness, agreeableness, emotional stability) offered both quicker and stronger financial relief. Our findings underscore the need to account for the personality of decision-makers when exploring decision-making during the pandemic, and during similar crisis situations.

Keywords: Personality, Political elites, COVID-19, Policy

1. Introduction

“The chancellor's [Angela Merkel] rigor in collating information, her honesty in stating what is not yet known, and her composure are paying off” (Miller, 2020).

“This is a man-made disaster, and that man is Donald Trump” (Tomasky, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced governments around the world to swiftly and simultaneously respond to a new and emerging crisis (Hale et al., 2021). Yet, countries have nevertheless had diverging responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, variying from near-total lockdowns (e.g., New Zealand) to few formal restrictions (e.g., Sweden) to promoting mass public gatherings (e.g., Nicaragua). The two characterizations above of the COVID-19 crisis highlight the influence that leaders are perceived to have had on outcomes, both in terms of policy responses and health consequences (cases and deaths). While the differing responses have typically been attributed to a variety of macro-level factors, for instance, economic, cultural, and political factors, as well as, demographic risk factors and limitations in medical infrastructure (e.g., Aldrich and Lotito, 2020; Frey et al., 2020), the scholarship has so far, to our knowledge, critically overlooked the micro-level characteristics of decision-makers.

Specifically, research on the personality of political leaders strongly suggests that their personality drives their actions once in office (e.g., Lilienfeld et al., 2012; Rubenzer et al., 2000; Watts et al., 2013). Human behavior is determined by individual differences; that is, different individuals behave differently when facing similar situations. This assumption has been confirmed over the past decades in countless studies showing how human personality – “who we are as individuals” (Mondak, 2010: 2) – shapes our social and political actions (e.g., Chirumbolo and Leone, 2010; Gerber et al., 2011; Vecchione and Caprara, 2009). Furthermore, leaders' personality traits have been portrayed as impacting their governments' policies (Greenstein, 1998; Owen and Davidson, 2009). Therefore, while it has been said that crises forge the character of leaders (e.g., Koehn, 2017), the reverse could also be true. In line with this proposition, the current analysis explores the following question: Do government leaders’ personality traits impact policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis?

While some studies have investigated this question for specific countries (e.g., in Sri Lanka, see Gunasekara et al., 2022), or described the association between leadership style and health outcomes (Medeiros, Crayne, Griffith, Hardy III, & Damadzic, 2022), large-scale comparative evidence about the psychological personality of leaders and their responses to the pandemic is still missing.

With this in mind, the current study assesses the extent to which the personalities of 61 heads of government (i.e., presidents or prime ministers) is associated with divergent responses to the COVID-19 crisis. We do so by regressing country-specific policy-responses (data from Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker initiative; henceforth, OxCGRT) against data on leaders’ personality traits measured before the onset of the pandemic via a large-scale comparative expert survey (NEGex; Nai, 2019), while controlling for important covariates. Our findings highlight the association of two personality meta-traits – “stability” (conscientiousness, agreeableness, emotional stability) and “plasticity” (extraversion, openness) – with both the magnitude and promptness of government responses. Ultimately, our results support the assumption that the personality of the leader is likely to be related to policy responses during a crisis, underscoring the need to account for this, generally overlooked, micro-level political factor in subsequent research focusing on outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic and other similar crisis situations.

2. Leaders, their personality, and policies

Politicians play an important role in policy-making. Research has shown that the composition of legislatures, the characteristics of the politicians that sit in them, not only influences the topics that are debated (Saalfeld and Kyriakopoulou, 2010), but also the actual policies that are ultimately enacted (Clayton and Zetterberg, 2018). Political leaders also impact policies. Legislative politics have become quite leader-centric in terms of image and decision-making (McAllister, 2007; Savoie, 2008). The scholarship demonstrates that a change of leadership generally entails a shift in policy positions for political parties (Adams et al., 2004). This is often also the case for governments; even if the governing party remains the same, as the change from Theresa May to Boris Johnson in the United Kingdom and from Rafael Correa to Lenin Moreno in Ecuador arguably illustrate.

Scholars have theorized that the aspects that derive political leaders’ capacity to influence policy reside around their personal backgrounds (e.g., Alexander and George, 1956). Particularly, personality traits of leaders have been highlighted as being associated with specific policy directions undertaken by their governments (Greenstein, 1998; Owen and Davidson, 2009). Specifically, the partisan and ideological preferences of political elites have been shown to align along the Big Five Inventory (BFI) (Hanania, 2017; Joly et al., 2018).

The BFI summarizes differences in human personality along five basic traits: extraversion (sociability, energy, charisma), agreeableness (cooperative and pro-social behaviors, conflict avoidance, tolerance, pleasantness), conscientiousness (discipline, responsibility, organization, dependability), emotional stability (calm, detachment, low emotional distress, low anxiety), and openness (curiosity, intelligence, and a tendency to make new experiences) (John and Srivastava, 1999; McCrae and John, 1992). Evidence from previous studies on the public at large and on political elites provides insights as to how these five personality traits of decision-makers could influence their response to a crisis (De Hoogh, Den Hartog, & Koopman, 2005; Fredrickson et al., 2003; Graziano et al., 2007; Riolli et al., 2002; Seibert and Kraimer, 2001). Indeed, the COVID-19 crisis presents an opportunity to explore this assumption. Based on the scholarship that demonstrates that leaders not only impact policy-making but that their personality traits have an influence on policy outcomes, we expect that a leader's personality is likely related to the policy-responses enacted during the COVID-19 crisis in terms of both magnitude and promptness.

Furthermore, the scholarship points to a simplified schema of the personality of public figures around two traits: “stability” and “plasticity” (Caprara et al., 2007; Silvia et al., 2009). That is, the five separate personality traits of the BFI align into two broader macro-traits. DeYoung and colleagues (2007; 2006) discuss these two “higher-order factors”. The first one includes converging agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability into what is termed the “stability” meta-trait. Based on research on agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability, the “stability” meta-trait would be associated with pro-social interactions, intelligence, and positive self-image (Hibbing et al., 2011; Hills and Argyle, 2001; Jensen-Campbell, Gleason, Adams and Malcolm, 2003). The second meta-trait, “plasticity” converges extraversion and openness, and would be associated with charismatic leadership and creativity (Bono and Judge, 2004; Mondak and Halperin, 2008).

Given the complex nature of the dynamics at play, we refrain from developing specific formal expectations for the effects of each of the two specific meta-traits. Nonetheless, existing evidence in social and political psychology literature suggests several avenues for potential effects. First, as a meta-trait “stability” is associated with stronger scores on conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability. All these traits seem intuitively associated with a stronger response, but also potentially with a more cautious (i.e., delayed in time) approach. Conscientiousness is often linked with stronger achievement orientation (working hard and persistence in the pursuit of individual goals), dependability (strong organizational skills and general responsible behaviors), and a marked preference for projection and planning (Judge et al., 1999; Seibert and Kraimer, 2001). Conscientious individuals perform well in challenging situations, where their discipline and proclivity for perseverance allows them to map and overcome the challenges they face (Hochwarter et al., 2000). Some evidence does indeed exist that a more “pragmatic” leadership style, focused on the most immediate issues and needs, was associated with fewer COVID-19 infections in the first months of the pandemic (Medeiros et al., 2022). At the same time, excessive conscientiousness can reflect “obsessionality, perfectionism, rigidity and slowness to respond” (Furnham, 2017: 1880), which could be associated with a more cautious and slow overall response to the crisis. Agreeableness is positively associated with empathy and a stronger urge towards helping behaviors, and individuals high in this trait are “more willing to risk negative outcomes to help others in both ordinary and extraordinary situations” (Graziano et al., 2007: 587), including strangers. Finally, emotional stability has been frequently associated with higher resilience in times of crisis (Fredrickson et al., 2003; Riolli et al., 2002), but also with low impulsiveness (Stanford et al., 2003). The second meta-trait, “plasticity,” is associated with higher scores on openness an extraversion. Openness is positively associated stronger resilience in times of crisis (Fredrickson et al., 2003; Riolli et al., 2002), whereas extraversion is often associated with social dominance and disinhibition (e.g., Newman, 1987), thus potentially with lower risk aversion. In this sense, this second trait could perhaps be associated in political leaders with a stronger and also a swifter response.

3. Data and methods

We investigate the relationship between leader personality traits and their country's response to the COVID-19 crisis by triangulating independent evidence from two data sources. Data for the governments' response to the COVID-19 crisis is collected from the OxCGRT initiative. Data for the personality traits of political leaders comes from the NEGex expert survey (Nai and Maier, 2018). Combining these two datasets provides information on the heads of government (presidents or prime ministers) in 61 countries in power during the onset and initial months of the COVID-19 crisis in early 2020, as well as the policy responses that these countries enacted during the first wave of the pandemic (covering the time period from January 1st to June 30th, 2020, corresponding to a total of 26 weeks). Fig. 1 illustrates the geographical coverage of our investigation. The list of all leaders included in our investigation and their personality profiles are reported in Table A1 in Appendix A .

Fig. 1.

Geographical coverage of the study.

3.1. Government responses to the COVID-19 crisis

In order to gauge the policy responses of countries during the pandemic, we rely, as others already have (Aldrich and Lotito, 2020; Frey et al., 2020; Kavakli, 2020), on the OxCGRT data, hosted by the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford (Hale et al., 2020). The OxCGRT dataset holds data on daily country-level policy responses of 170+ countries worldwide starting in January 2020. The policy response data includes several dimensions of the governments’ responses to the pandemic. In the current analysis, we select three indicators as our dependent variables based on the extent to which the national leadership may influence these policies, as described in more detail below. For more information on the project and the data: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker.

Given that the OxCGRT data bases the majority of their indicators on the most stringent government policy that is implemented in a country, the dataset applies policies implemented at the regional or local level to the entire country. Only two out of 18 indicators reported in the OxCGRT dataset are limited to policies exclusively enacted by national governments: restrictions on international travel and the implementation of debt/contract relief for households. The former records the presence of specific restrictions on international travel using a five-point ordinal scale: 0 (no measures in place), 1 (screenings), 2 (quarantine on arrivals from high-risk regions), 3 (ban on arrivals from some regions) and 4 (ban on all regions or total border closure). The latter, which we label as “Financial Relief”, measures the extent of financial interventions provided to households, such as measures to stop loan repayments. It uses a three-point ordinal scale: 0 (no relief), 1 (narrow relief, specific to one kind of contract) and 2 (broad debt or contract relief). In summary, these two indicators directly measure national policy responses to external risk (e.g., arrival of infection from abroad) and towards internal citizen-centered difficulties (e.g., unemployment, domestic economic situation).

Additionally, we also included a third indicator: the overall government response index. This composite index tallies countries' responses to all 18 indicators: the cancellation of public events, restriction in gatherings, stay-at-home requirements, restrictions on internal movement, testing policies, etc. This index broadly reflects the breadth of the governmental response to the crisis and has been standardized to vary between 0 (no measures taken) to 100 (maximum level). While this index applies policy decisions taken at the regional and local levels in a countrywide manner, we nevertheless decided that it would be important to investigate the impact of national leaders' personality on an overall policy response during such an extraordinary national emergency. Indeed, prior work has shown that central governments can impact the policy choices of sub-national units (Allen et al., 2004). Furthermore, recent research on central governments’ response to COVID-19 has also utilized this OxCGRT indicator in such a manner (Aldrich and Lotito, 2020; Kavakli, 2020).

Moreover, for each of the three policy responses selected, we have used two different measures of responsiveness: (i) the average level of responsiveness in each country over the 26-week period under investigation (i.e., magnitude), and (ii) the rapidity of the response implemented by the government, measured as the total number of days at the minimum level on the indicator (i.e., promptness). The promptness variable intends to measure the number of days that the country stayed at the minimum level of response since Jan 1, 2020, hence it is a proxy for how quickly (or, slowly) the country moved away from ‘zero’ response. Also, days at maximum response-level was not selected as an outcome due to the possibility of censoring (i.e., certain countries may not have reached the maximum response level for all policy types during the study timeframe ending in June 30, 2020).

Taken together, these two variables reflect, for each country, the average intensity of the government response, and the delay in initiating a response. While it is important to note that there exists important similarities and clustering in countries’ policy responses to the COVID-19 health crisis, especially at the beginning – around mid-March 2020 – of the pandemic (Hale et al., 2021), the cases analyzed in this study display a broad variation with respect to magnitude and promptness across the range of the different policy indicators used in our analyses (see Table B2 in Appendix B). Figures C1, C2 and C3 in Appendix C display heat maps, which also summarize the differences in the average responsiveness for all three interventions across the study time frame (26 weeks) for each country.

3.2. Leaders and personality traits

The personality traits of government leaders are the main independent variables under investigation. These data were ascertained from the NEGex dataset (Nai, 2019). This dataset surveys a country-specific sample of scholars with expertise on elections and their country's politics. Experts are surveyed following each national election (since June 2016).

On average, 6.2 experts provided personality ratings per leader. Scholars in the dataset tended to lean left-of-center (M = 4.26/10, SD = 1.78), 76% were native to the country they resided in, and 28% were female. Overall, experts were very familiar with the elections (self-rating, M = 8.19/10, SD = 1.66). Importantly, the leaders’ personality traits included in the dataset are measured before the COVID-19 crisis, thus ensuring the absence of endogenous effects between how leaders handled the crisis and their assessed personality. One exception is Leo Varadkar, who was Irish Prime Minister at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. The NEGex expert survey data was collected after the February 8, 2020 election in the Republic of Ireland; thus, within the period under investigation in this study (January 1- June 30, 2020). However, the election took place several weeks prior to the first recorded COVID-19 case in that country (February 29, 2020).

Importantly for our purpose, the NEGex dataset includes variables that measure the personality traits of key candidates/party leaders for each election. For instance, for the 2016 US Presidential election experts were asked to evaluate the personality of both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. Experts were randomly assigned to either candidate (e.g., either Trump or Clinton), to ensure that their ratings do not reflect any direct comparison between the different personalities at play but only focus on one specific candidate. The NEGex questionnaire includes the Ten Items Personality Inventory (TIPI) (Gosling et al., 2003); experts were therefore asked to rate ten statements about the personality of the candidate (e.g., are they “critical, quarrelsome”, “dependable, self-disciplined”) on a scale from 0 “very low” and 4 “very high.” Pairs of statements, one positively and one negatively framed, reflect each of the five traits.

In terms of data validity for the measure of personality, several studies have shown significant cross-observer agreement - that is, external observers can rate the personality of other persons in a way that is consistent with the self-assessment of the latter (e. g, McCrae and Costa, 1987; Moshagen et al., 2019). Evidence suggests that external observers also tend to agree with each other rather consistently (Vazire, 2006, 2010). This should be especially likely for figures that are as constantly in the public spotlight as political leaders. In the data, the average standard deviation across the five traits for all candidates – that is, how much experts on average “converge” on the ratings they provided – is around 0.98 (personality variables range between 0 and 4). Experts seem to be slightly more consensual when it comes to the candidates' emotional stability (SD = 0.93), and slightly less consensual about the candidates' openness (SD = 1.03). Despite certain limitations, we are confident to rely on aggregated expert assessments, which provide a systematic, comparable, and reliable measurement of leaders’ personality traits.

The personality traits of political leaders are not independent constructs. The results (see Table B1 in Appendix B ) of principal component analysis show the existence of two orthogonal underlying personality dimensions, explaining respectively 49% (Dimension 1) and 32% (Dimension 2) of the variance; in line with the findings of DeYoung (2006). The first dimension is characterized by strong scores on conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability, thus reflecting “stability”. The second is characterized by high scores on extraversion and openness, reflecting “plasticity.” We therefore computed two “meta-traits” additive indexes that reflect the two underlying dimensions (respectively, α = 0.83 for stability and α = 0.73 for plasticity).

The distribution of the 61 leaders in the current analysis on the two personality meta-traits (Figure B1 in Appendix B) shows that on average national leaders tend to score above the midpoint on both indicators. As an example, Donald Trump scores the lowest among all 61 candidates on stability, whereas Jacinda Ardern scores the highest. In terms of plasticity, Daniel Ortega scores the lowest across all candidates, and Justin Trudeau scores the highest among all candidates on this personality meta-trait.

3.3. Control variables and models

Our models adjust for political, demographic, health system, and economic characteristics that are likely associated with the policy responses to the pandemic. First, we adjusted for numerous sources of potentially important political and social variability. For instance, in line with results discussed by Kavakli (2020), our models adjust for an important political characteristic: populism. We identified whether the leaders are “populist” (or lead a populist party) or not, based on classifications from comparative literature (e.g., Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2008; Mudde, 2007) and existing inventories such as the PopuList (Rooduijn et al., 2019). We also adjust for regime type, which has been associated with differential responses to the COVID-19 crisis (Frey et al., 2020). More specifically, we control for the Combined Polity Score from the Polity Project – a composite index compiled by the Center for Systemic Peace and ranging from −10 (strongly autocratic) to +10 (strongly democratic); for more information: http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html.

Second, we have also controlled for factors that may reflect a country's ability to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., demographics and health system strength), which can in turn influence policy responsiveness. More specifically, seeing that the pandemic has had its most severe impact on older populations, we adjust for the proportion of individuals aged 65 years and older, while also adjusting for differences in terms of health system capacity (i.e., number of hospital-beds per 1,000 individuals). We also adjust for the mortality (i.e., cumulative reported deaths per 10,000 individuals between from January 1 to June 30, 2020), as well as the time elapsed since the identification of the first 100 cases until the end of the study time-frame (June 30, 2020). These factors were adjusted for in order to account for differences in both the severity and the timing of the crisis across different countries that may influence the magnitude and timing of different policy responses. The data for health and pandemic-related factors were all collected from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020).

Third, seeing that many of the policy responses have had profound economic implications during this period and given that the ability to implement certain measures will likely depend on a nation's fiscal capacity (Arellano et al., 2020), we also adjusted for the debt-to-GDP ratio of the national government. Data for this economic variable was collected from the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2018). Moreover, since travel restrictions have had a devastating impact on tourism (Nicola et al., 2020), we also accounted for a country's economic dependence on that industry while exploring the correlates of international travel controls. To do so, we used international tourism receipts (as a percentage of total exports) data from the World Bank (World Bank, 2018).

Finally, as previously indicated, the overall government response outcomes include policies enacted at sub-national and national levels alike, necessitating an adjustment for the level of decentralization of countries included in the analysis. We collected data on the level of regional autonomy in each country from the Regional Authority Index (Hooghe et al., 2016). Specifically, to account for this, we use the n_policy variable, which is on a 5-pt scale that we interpret as ranging from 0 (highly centralized) to 4 (high decentralized).

Because the outcomes that are averages are continuous, we use OLS regressions to estimate the relationships between the magnitude of the response (average score) outcomes with the predictors. With respect to the promptness of the response (number of days at the minimum), we employ count regression models. Diagnostic tests strongly suggest that the alpha parameter for the regressions with the count outcomes is not zero; we therefore use negative binomial regression models rather than the Poisson regression models (see Cameron and Trivedi, 2013). Descriptive statistics for all variables (dependent variables, personality traits, covariates) are presented in Table B2 in Appendix B.

All data and codes are available for replication at the following anonymous OSF repository: https://osf.io/rb2zq/.

4. Results

We present below results of linear and negative binomial models on the three indicators of government response: international travel controls, financial relief, and overall government response. For each policy response indicator, we estimated both its magnitude (average level) and promptness (number of days at minimum level).

4.1. International travel controls

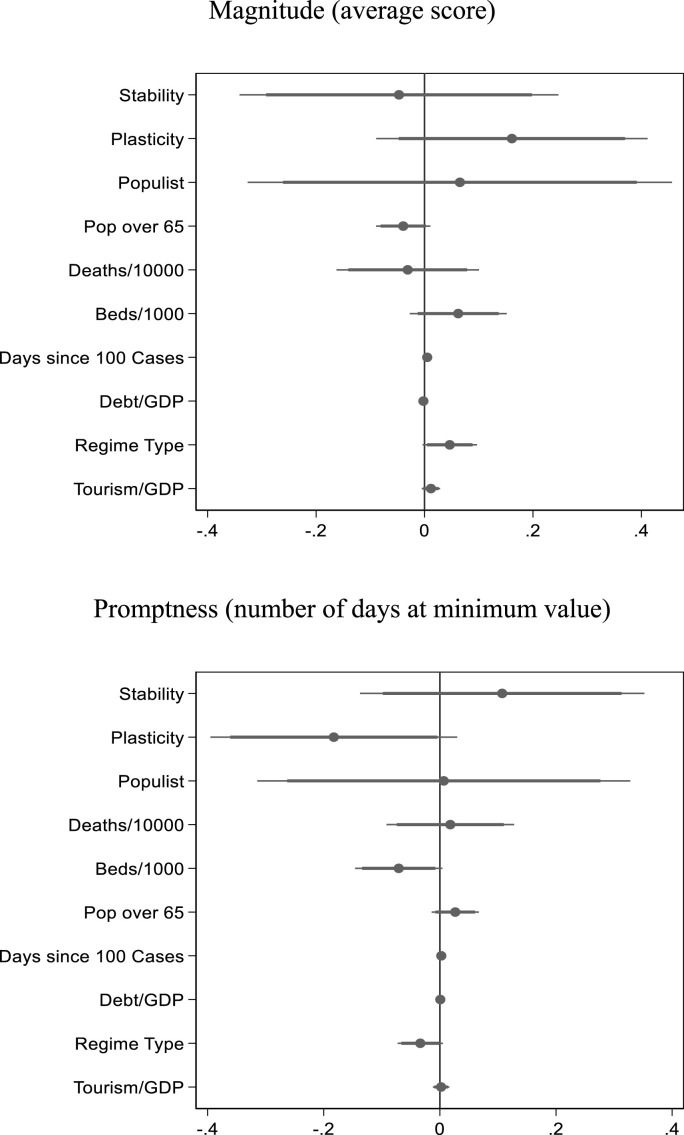

While the results, displayed in Fig. 2 (top panel), indicate that the personality of the leaders has no statistical relationship with the magnitude of international travel controls implemented during the first wave of the pandemic, they do demonstrate that the personality of the government leaders is statistically associated with the promptness of international travel controls implemented by countries during the first wave of the pandemic, as displayed in Fig. 2 (bottom panel). Specifically, governments headed by leaders scoring higher on the plasticity trait implement travel restrictions more rapidly (at p < 0.1).

Fig. 2.

Correlates of international travel controls.

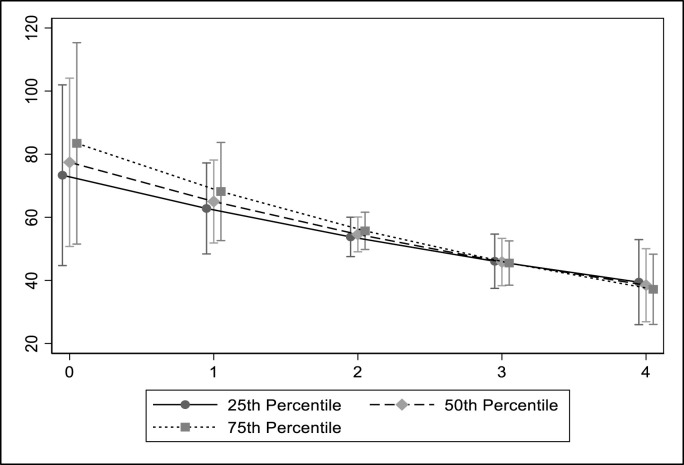

Given the importance that economic dependence on foreign travelers might have on any policy decision to limit international travel, we also examined the possible moderating role of this variable on the association between national leaders’ personality and international travel controls. We found that Tourism/GDP does indeed moderate the relationship between the time taken to initiate a policy response on travel and the “plasticity” trait. The results, in Table B14 in Appendix B, do not show that the interaction term in this model is significant. Nevertheless, we estimate the marginal effects of this interaction, as is recommended in the literature in interpreting interactions in order to detect moderating differences (Brambor et al., 2006; Franzese and Kam, 2009; Kingsley et al., 2017). Fig. 3 does in fact show that countries at the 50th and 75th percentile of the Tourism/GDP variable and whose leaders scored at the highest end of their “plasticity” trait spent significantly (at p < 0.05) 39 and 46 days less at the minimum level of travel restrictions respectively compared to countries at the same Tourism/GDP percentiles with leaders scoring at the lowest end of that personality scale. As for countries with a lower economic dependence on foreign travelers, while a negative moderating relationship is also noticeable for those at the 25th percentile of the Tourism/GDP variable, this relationship is smaller and not significant. Therefore, these findings attest to leaders from countries highly dependent on foreign travel being quicker to impose international travel restrictions if they scored very high on the “plasticity” trait.

Fig. 3.

Moderation of Tourism/GDP on the impact of plasticity on international travel controls (number of days at minimum value).

The findings of our analyses on international travel controls support the assertion that leaders' personality is related to governments’ restrictions on international travel. Specifically, countries with leaders scoring higher in “plasticity” were quicker to implement international travel restrictions, and thus responded more rapidly to the COVID-19 crisis.

4.2. Financial relief

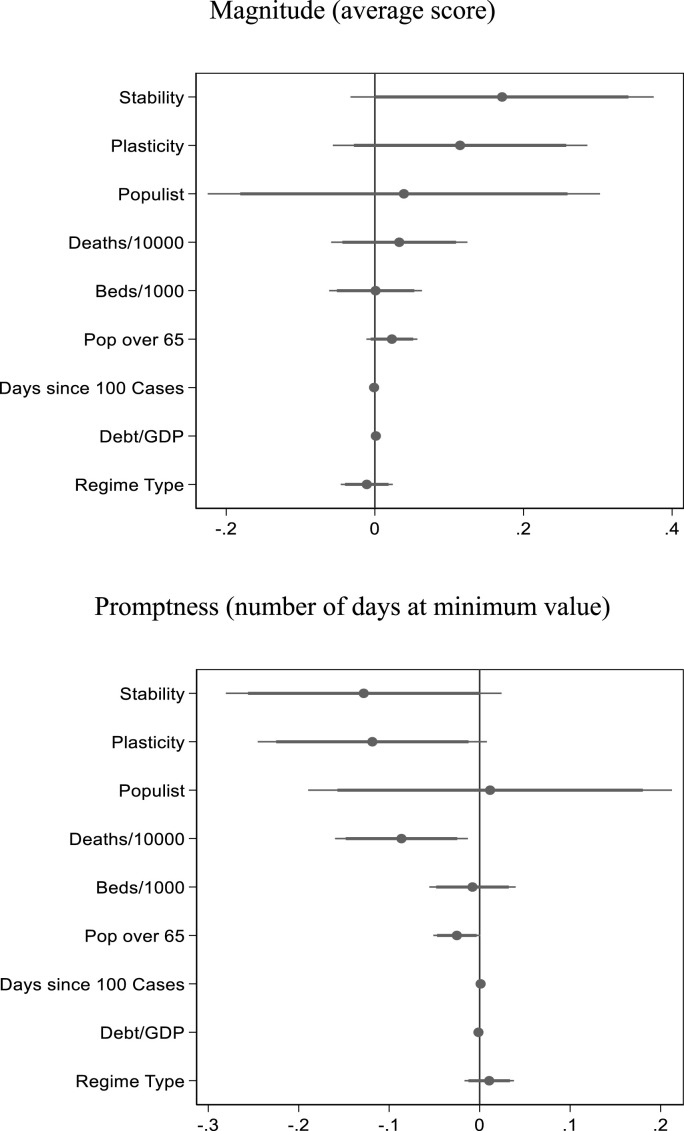

The findings also demonstrate that the personality of world leaders is statistically associated with the average financial relief policies implemented by countries during the first wave of the pandemic, as displayed in Fig. 4 (top panel); most notably in terms of leaders’ “stability; ” the higher that a leader scored on this trait the more financial help their government provided to its citizens (at p < 0.1). To better assess the magnitude of this relationship, predicted probabilities were computed and are displayed in Figure B2 in Appendix B. The results show that moving from the low end of the “stability” scale to the high end leads to a rather considerable 0.69-pt (on a 3-pt scale) increase in the average financial relief that was provided by countries. For its part, the “plasticity” personality trait is not shown to be statistically related to the average financial relief.

Fig. 4.

Correlates of financial relief.

Fig. 4 (bottom panel) also shows that both meta-traits display a negative and significant (at p < 0.1) relationship with the time taken to provide financial relief to citizens. Countries with leaders who scored high on these attributes were quicker in providing financial aid. Essentially, these countries appear to have been more willing to address their populations’ financial difficulties during the COVID-19 crisis. Figure B3 in Appendix B displays the substantive impact that the meta-traits have on this outcome. The results show that countries with a leader who scored at the highest end of the “stability” trait, compared to those scoring at the lowest end of the scale, had 50 fewer days without any financial relief; whereas countries with a leader who scored at the highest end of the “plasticity” trait, compared to those scoring at the lowest end of the scale, had 46 fewer days without any financial relief. All in all, the personality of government leaders displays consistent associations with the actions that their country took to financially assist its population.

Lastly, the data on financial relief stand out for Spain, see Figure C2 in Appendix C. We therefore performed the analyses with the financial relief outcomes excluding Spain. The results (not reported) are very similar to those presented. However, an important difference is that the relationships between the “stability” trait and the average level of financial relief no longer crosses the threshold of significance, rather being very close at doing so at p = 0.12.

The findings clearly support the notion that government leaders’ personality has an association with financial relief policies during the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis.

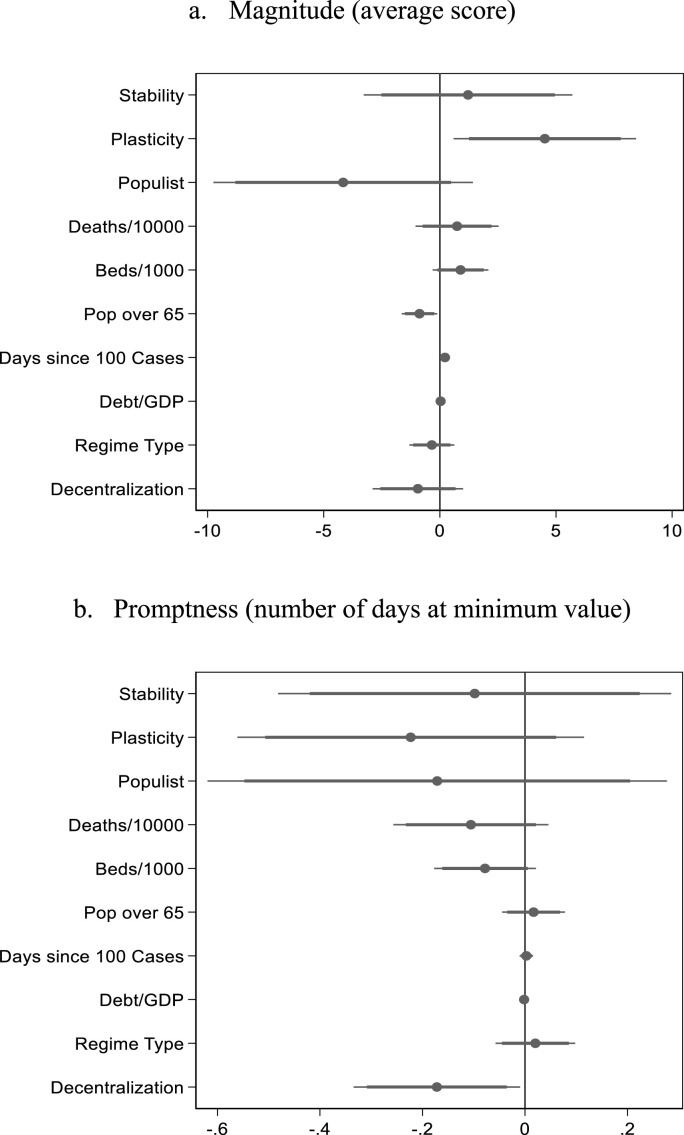

4.3. Overall government response

As in the other outcomes, we once again find that the personality of government leaders is associated with the overall government response towards the COVID-19 crisis. The analysis of the average overall government response, in Fig. 5 (top panel), demonstrate that the “plasticity” meta-trait is statistically related (at p < 0.05) in a positive manner to overall policies enacted by a country in response to the crisis. In other words, a country in which the leader scored high on the “plasticity” trait is more likely to have had greater average government intervention in response to the COVID-19 crisis. Predicted probabilities, see Figure B4 in Appendix B, show that going from the low end of the “stability” scale to the high end leads to a 13-pt increase on the average overall government response. However, no statistical relationship is shown for the “stability” personality trait. As for the promptness of the overall government response, neither of the personality meta-traits demonstrate a significant relationship with this outcome (Fig. 5, bottom panel).

Fig. 5.

Correlates of overall government response.

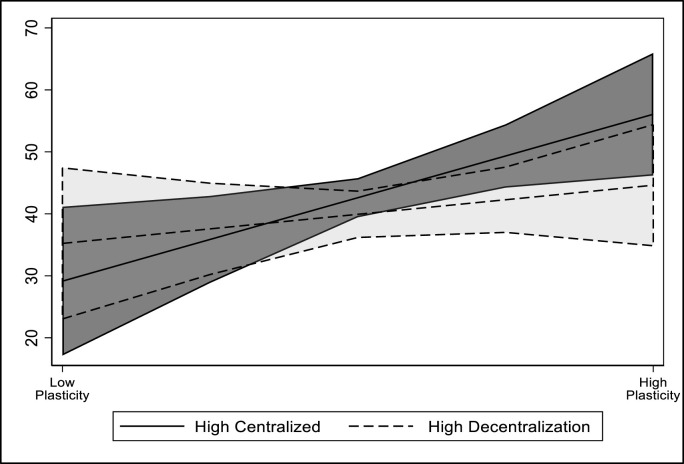

Because the overall government response metric builds on the most stringent policies countrywide, this parameter can reflect decision-making at the regional or local levels alike. It is, therefore, necessary to verify the moderating role of decentralization on the impact that the national leaders' personality may have on the average overall government response outcome. Essentially, this relationship should be more pronounced in centralized countries since the national governments of such countries are directly responsible for a larger range of policies. While the results, in Table B14 in Appendix B, do not show a significant interaction term, the findings displayed in Fig. 6 do nonetheless support this assertion. The “plasticity” personality meta-trait of government leaders from highly centralized countries has, from the low end of the stability scale to the high end, a 27-pt and significant (at p < 0.05) increase on the average overall government response. While the same positive relationship is also present in highly decentralized countries, it is much smaller and not significant. Therefore, the impact of national-level leadership is much more pronounced in more centralized countries, as expected. These results ultimately support the use of the overall government response variables in our analyses and further strengthens the proposition that policy-makers’ personality type can directly influence decision-making during a national emergency.

Fig. 6.

Moderation of decentralization on the impact of plasticity on government response (average).

The analyses of the overall government response do support the assertion that the personality of the leaders can impact the overall policies that have been implement in response to the COVID-19 crisis. Albeit, this appears to be moderated by the extent to which different levels of government are involved in decision-making vis-à-vis national leadership. Moreover, only “plasticity” is shown to have a statistical relationship with only one of the two outcomes; this may be related to the promptness measure being unduly influenced by the different levels of decentralization across countries.

Ultimately, this series of analyses demonstrate that the personality traits of government leaders have been associated with the policy responses during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the findings do not show a ubiquitous impact of government leaders’ personality on COVID-19 related policies, they show nonetheless that leaders scoring high on “plasticity” were more prompt to implement travel restrictions and provide financial relief and offered a stronger response in general (average overall response), whereas “stable” leaders displayed both a stronger and more rapid response to the pandemic in terms of financial relief.

4.4. Additional analyses

Firstly, given the relatively small number of observations, we also ran the analyses with imputed data in order to compare the results estimated from these data with those from complete case analysis (listwise deletion), see Tables B3 and B4 in Appendix B (Arel-Bundock and Pelc, 2018; Sidi and Harel, 2018). Missing data on predictors were imputed, prior to the regression analyses, using multiple imputation by chained equations methods generating 20 imputed datasets using all collected variables contained in the original dataset with 200 iterations per imputation. As far as the personality traits are concerned, the relationships between “plasticity” with the promptness in implementing travel controls and financial relief measures are no longer significant with the results estimated from the imputed data. However, the other three statistical relationships that were highlighted between leaders’ personality and the outcomes of government policy responsiveness remain significant in the analyses with imputed data. Even though the number of observations is lower by 7 (from 61 to 54) for international travel controls and financial relief and by 20 (from 61 to 41) for overall government response with the complete case data, two additional relationships are shown to be significant with the complete case data.

Also, as presidential systems can be more leader-focused, it is plausible that the personality of a president may have a greater impact on policies than that of a prime minister. We added this variable as a control in the models, see Tables B5 and B6 in Appendix B. The inclusion of this control variable leads to four of the five statistical relationships no longer being significant; only the association between the “plasticity” meta-trait and the magnitude of the overall government response remains significant. However, when evaluating results using the imputed data with greater statistical power, the relationship between “stability” and the promptness of financial relief remains significant with the addition of the system of government variable.

We also investigated the potential moderating role of the system of government on the relationships between personality and the policy responses that were found to be significant in the previous analyses. We found two significant moderating relationships. Though Table B14 in Appendix B does not present a significant interaction term, Figure B5 and Figure B6 in Appendix B display statistical moderating impacts of the system of government. Figure B5 shows that the “stability” of presidents, from the low end of the “stability” scale to the high end, corresponds to a rather strong and significant (at p < 0.05) increase on the average financial relief provided by governments. Whereas Figure B6 demonstrates that the “plasticity” of prime ministers, from the low end of the variable scale to the high end, is associated with a significant (at p < 0.1) decrease in the number of days of the minimum level on international travel controls.

Furthermore, while the sex of politicians has been linked to different policy outcomes (Clayton and Zetterberg, 2018), research has so far failed to identify a relationship between the sex of the national leader and policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis (Aldrich and Lotito, 2020). We nevertheless decided to adjust for the sex of the government leaders. The results in Tables B7 and B8 in Appendix B are essentially the same for the personality traits as our main results.

Moreover, seeing as the cultural characteristics of countries can relate the COVID-19 outcomes (Erman and Medeiros, 2021), the models were additionally adjusted for national cultural traits. Specifically, as individualism has been demonstrated to have an impact on the evolution of the COVID-19 crisis (Dryhurst et al., 2020; Frey et al., 2020), we adjust for this cultural factor. The data on cultural characteristics of each country were collected using the Hofstede model (Hofstede et al., 2010); for more information: https://geerthofstede.com/research-and-vsm/dimension-data-matrix/. The results presented in Tables B9 and B10 in Appendix B, do not display a statistical association between a personality meta-trait and an outcome with the complete case data when individualism is added to the model. This is likely due to the loss of a large number of observations resulting from the addition of this variable to the models. When estimating the results from the imputed data, the relationships between “stability” with both the average and promptness of the financial relief remain significant, as does the association between “plasticity” and the average government response.

Additionally, recent scholarship has highlighted that electoral concerns can help to explain governmental responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (Pulejo and Querubín, 2021). In order to adjust for such electoral calculations that leaders might have, and to account for the different systems of government in our data, we calculated the days since the leaders’ (most recent) election until the end of the study time-frame (June 30, 2020). If electoral concerns do relate to COVID-19 policy responses, such a dynamic should be present the further the leaders were from their election day. The results of the analyses, in Tables B11 and B12 in Appendix B, demonstrate that the inclusion of this variable leads to three significant associations between the personality meta-traits and the policy outcomes; the relationships between “stability” and the average of financial relief as well as “plasticity” and the promptness of international travel controls are no longer significant.

Finally, the personal preferences of the experts used to ascertain the personality trait might impact the accuracy of their evaluation. Though Nai and Maier (2021) have shown that the experts tend to be substantially less influenced by their political preferences than regular citizens, we nevertheless erred on the side of caution and computed “adjusted” measures of candidates' personality traits to account for experts' personal bias (see Walter and Van der Eijk, 2019). For each candidate in the dataset, we regressed their scores on the five personality traits on the difference between their partisan identification and the average expert left-right position (that is, how “ideologically distant” the expert sample and the candidate they evaluated are). In a second step, we saved the regression residuals - that is, the part of the dependent variable (personality traits) that is not explained by such ideological distance – into new variables. We, in other terms, computed measures of candidates’ personality traits that are independent of the ideological distance between the (average) expert and the candidates themselves – “the perception from which partisan biases have been eliminated” (Walter and Van der Eijk, 2019: 372). These measures are net of the ideological distance between the average expert and the candidate they had to evaluate. The adjusted measures for the Big Five personality traits also loaded in a similar manner on two orthogonal meta-traits. We performed the analyses with the “adjusted” personality meta-traits and the findings in Table B13 in Appendix B for the two personality traits are essentially the same.

In summary, the results support that the personality of world leaders was statistically associated with the policy responses enacted towards the pandemic. While not all of the policy responses demonstrate a relationship with the two personality traits, there are several statistical associations between government leader's personality traits and policy responses that supports their importance. While no causal claims can be advanced with the data at hand, our results suggest a potential a link between leaders' personality traits and the policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis enacted by their countries.

5. Discussion and conclusion

During the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, general observers had drawn comparisons between world leaders' responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and their character (e.g., Mkhondo, 2020; Taylor, 2020). Much has been written for example about the lackluster response of the US government to the crisis, from repeated denials about the gravity of the situation to late testing protocols and the absence of precise behavioral recommendations (e.g., Yong, 2020). In the case of Germany, its ability to avert the high mortality seen in some of its European neighbors had been specifically attributed to Angela Merkel (Miller, 2020). The comparative ineffectiveness of the US in handling the COVID-19 crisis has also been attributed to its leadership (e.g., Miller, 2020; Tomasky, 2020). However, the plausible link between leaders’ personality and policy responsiveness towards the COVID-19 crisis has never been empirically assessed. In this study, we tackle this scholarly gap and explore the extent to which the initial policy response to the pandemic is related to the personality traits of current world leaders.

Specifically, we investigated the relationship between leaders’ personality and policy responses towards the COVID-19 crisis by triangulating evidence on government responsiveness during the first-wave (1 January 2020 to 30 June 2020) of the pandemic (OxCGRT) and data from the NEGex comparative expert survey (Nai, 2019), which allows to map the personality profile of current heads of government (measured before the onset of the pandemic). Controlling for important macro-level covariates expected to drive the country response to the crisis, and focusing particularly on two personality meta-traits – “stability” (conscientiousness, agreeableness, emotional stability) and “plasticity” (extraversion, openness) – our models show that the individual personality of political leaders should not be ignored.

In brief, our analyses indicate that leaders scoring high on “plasticity” tend to provide stronger overall responses (average) and act more rapidly in implementing travel restrictions and providing financial relief. Furthermore, leaders scoring high on “stability” offer a stronger and more rapid response in terms of financial relief. While the findings do not show a ubiquitous relationship between government leaders' personality and COVID-19 related policies, they are generally consistent with the overall expectation that governments' response to the COVID-19 crisis can be related to their leaders’ personality.

From a theoretical standpoint, our results deepen our understanding of the areas in which the personality of leaders is likely to matter. Growing evidence shows that the performance of elected officials is, in part, driven by their personality profile (Ramey et al., 2017; Watts et al., 2013). In terms of policy, while research has previously highlighted the importance of leaders' personality on government policies (e.g., Greenstein, 1998; Owen and Davidson, 2009), this scholarship is surprisingly rather limited. Our results are therefore generally consistent with findings that demonstrate that politicians’ personality relate to their political behavior, and underscore the need to account for individual differences in national leadership with respect to policy-making, specifically in response to a crisis. Therefore, studies that focus on crises – such as global climate change, the depletion of natural resources, mass refugee migration, etc. – need to consider the role of the personality of political elites in order to develop a thorough understanding of such phenomena.

From a practical standpoint, our analyses suggest that studies, which investigate policy decisions-making should account for the potential impact that the personal attributes of decision-makers may have on policy decisions, in conjunction with more the commonly examined structural, political, and social factors. If, as we have shown in the current study, differences in the personality of political leaders can relate to the trajectory of governmental responses to such a global crisis, then the medium- and long-term consequences of the COVID-19 crisis itself will be, at least in part, a function of these personality differences. To be sure, the personality of leaders cannot be expected to have an overarching direct effect on policy; even when assuming that leaders can dictate policies directly, many factors come into play during implementation. Nonetheless, we demonstrate that the personality of the leader is associated with the policies set in place; either because their character influences the overall style of the administration, or because local leaders, bureaucrats and civil servants may align with the leader to signal allegiance. Regardless of the specific mechanisms at play, which are beyond the scope of our investigation, good reasons exist in expecting an association between a leader's personality and the outputs of their government.

Further, our findings also highlight an important methodological point, particularly with respect to the use of OxCGRT data. We demonstrate that the overall government response index is in fact conditional on the level of decentralization in a given country. For instance, we find that the relationship between the “plasticity” meta-trait and the average overall government response is moderated by the level of decentralization. While the OxCGRT data is frequently used to inform a rapidly expanding body of evidence around the COVID-19 pandemic, to our knowledge no study has yet explored the impact of decentralization on OxCGRT indicators, which code sub-national policies in a countrywide manner. Therefore, all future research exploring the relationship of almost all the OxCGRT indicators (except international travel restrictions and financial relief) should account for the level of decentralization of each country.

Similarly, we also find evidence of moderation regarding the system of government. While the personality of presidents is shown to moderate in part the relationship between the “stability” meta-trait and the average financial relief, the personality of prime ministers is also demonstrated to moderate the association between the “plasticity” meta-trait and the promptness of international travel controls. Substantively, replacing a government leader with the “wrong” personality attributes is arguably easier in a parliamentary system than a presidential one (especially in countries such as Australia). Although institutional and political barriers might complicate the process to change a head of government, future research should nevertheless endeavor to explore which “types” of leaders persevere or fall during crises.

Still, while our research provides novel and interesting insights into how a national leader's personality may relate to decision-making during a national emergency, the study does have its limitations. The findings likely reflect conservative estimates because a leader's personality cannot be expected to single-handedly drive government policies – especially in terms of complex and multifaceted crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the exact mechanisms that explain why certain meta-traits impacted specific policy responses but not others remain unknown.

Another issue might relate to the relatively low number of cases that this study explores. We conducted a power analysis with the following parameters: effect size (f2): 0.1; α: 0.1; power: 0.8; and number of predictors: 10. Seeing that recent scholarship has found that leaders' personalities coincide with COVID-19 outcomes in a manner that relates to a medium effect size (Medeiros et al., 2022), we believe that expecting a small to medium effect size measure is reasonable. The results of the power analyses that we conducted demonstrated that a total sample size of 47 cases was necessary for our analyses. The models on overall government responses estimated from the complete case data might hence be problematic; however, the results estimated from the imputed data for this outcome are quite similar. Ultimately, it is nonetheless possible that the significance level of some of the relationships might be adversely impacted. Nevertheless, a greater number of observations would increase the probably of demonstrating significance between the personality traits and the policy outcomes. At the very least, the current study conservatively establishes that a leaders’ personality traits correlate with some of the policy responses that were put forth during the pandemic.

Moreover, though we argue for the importance of considering micro-level political factors such as personality in subsequent investigations, exploring politicians' personalities is ripe with difficulties. While self-reported survey data from the politicians themselves might be the standard (e.g., Joly et al., 2018; Schumacher and Zettler, 2019; Scott and Medeiros, 2020), this approach becomes unrealistic for large-scale comparative studies. Furthermore, it is unlikely that high-profile political leaders – presidential candidates, party leaders, prime ministers, and so forth – would agree to volunteer their insights into their own personality; the chances to get leaders the like of Donald Trump, Benjamin Netanyahu, Boris Johnson or Jair Bolsonaro to answer a questionnaire are virtually non-existent. As an alternative to self-reports, recent work has been developed to estimate the personality of political figures via the systematic analysis of secondary data, such as parliamentary speeches, by implementing machine learning techniques (Ramey et al., 2017). We, however, highly recommend the usage of experts' surveys, as we have done so in this study. This is a proven technique that allows to relatively easily and reliably measure politicians’ personality (Nai and Maier, 2018; Nai and Martinez i Coma, 2019; Visser et al., 2017). However, regardless of the technique used to measure personality traits in leaders, our study demonstrates that scholars should account for such political factors when exploring policy-making, especially in times of crisis.

Finally, while it is beyond the scope of our investigation to quantify the effects of leaders’ personalities on the health and economic consequences of the crisis (e.g., causalities, magnitude of the economic downturn, etc.), we nevertheless believe that future research should explore these relationships as well. Since the character of leaders can partly drive the initial responses to the crisis, the leaders themselves can even be seen as somewhat responsible for these undesirable effects. Thus, who is in charge during a crisis matters and these phenomena should be thoroughly explored.

Specifically, regarding the COVID-19 crisis, our study is a glimpse into the predictors of policy responses for the first initial phase of the pandemic. As this crisis continues for, at least, the near future and evolves around the world, research will have to be careful to account for the manner in which the relationships of predictors with specific outcomes might be conditioned to specific phases of the pandemic. Yet, regardless of how this crisis evolves, experts tasked with developing policy responses towards the pandemic should more explicitly consider the personality of government leaders when proposing, discussing and communicating policy alternatives.

Author contributions

M.Medeiros, A.Nai, A. Erman and E.Young contributed to the study design, data collection, interpretation of the results and the drafting of the manuscript. M.Medeiros and A.Nai analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and gave final approval for the version to be published.

Financial Support

A.Nai acknowledges the financial support of the Swiss National Science Foundation, grant No. P300P1_161,163.

Replication materials

All data and codes are available for replication at the following anonymous OSF repository: https://osf.io/rb2zq/.

Declaration of competing interest

M.Medeiros, A. Nai, A. Erman and E. Young declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115358.

Appendix ASupplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

All data and codes are available for replication at the following anonymous OSF repository: https://osf.io/rb2zq/.

References

- Adams J., Clark M., Ezrow L., Glasgow G. Understanding change and stability in party ideologies: do parties respond to public opinion or to past election results? Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2004;34(4):589–610. [Google Scholar]

- Albertazzi D., McDonnell D. Palgrave; Houndmills: 2008. Twenty-first Century Populism: the Spectre of Western European Democracy. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich A.S., Lotito N.J. Pandemic performance: women leaders in the covid-19 crisis. Polit. Gend. 2020:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L., George J.L. Dover; New York: 1956. Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House. [Google Scholar]

- Allen M.D., Pettus C., Haider-Markel D.P. Making the national local: specifying the conditions for national government influence on state policymaking. State Polit. Pol. Q. 2004;4(3):318–344. [Google Scholar]

- Arel-Bundock V., Pelc K.J. When can multiple imputation improve regression estimates? Polit. Anal. 2018;26(2):240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano C., Bai Y., Mihalache G.P. 2020. Deadly Debt Crises: COVID-19 in Emerging Markets (0898-2937)https://www.nber.org/papers/w27275 Retrieved from Cambridge: [Google Scholar]

- Bono J.E., Judge T.A. Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004;89(5):901. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambor T., Clark W.R., Golder M. Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Polit. Anal. 2006;14(1):63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron A.C., Trivedi P.K. Cambridge Cambridge university press; 2013. Regression Analysis of Count Data. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara G.V., Barbaranelli C., Chris Fraley R., Vecchione M. The simplicity of politicians' personalities across political context: an anomalous replication. Int. J. Psychol. 2007;42(6):393–405. [Google Scholar]

- Chirumbolo A., Leone L. Personality and politics: the role of the HEXACO model of personality in predicting ideology and voting. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2010;49(1):43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton A., Zetterberg P. Quota shocks: electoral gender quotas and government spending priorities worldwide. J. Polit. 2018;80(3):916–932. [Google Scholar]

- De Hoogh A.H.B., Den Hartog D.N., Koopman P.L. Linking the Big Five‐Factors of personality to charismatic and transactional leadership; perceived dynamic work environment as a moderator. J. Organ. Behav.: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior. 2005;26(7):839–865. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung C.G. Higher-order factors of the Big Five in a multi-informant sample. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006;91(6):1138. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryhurst S., Schneider C.R., Kerr J., Freeman A.L.J., Recchia G., Van Der Bles A.M.…van der Linden S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1098/rsos.201199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erman A., Medeiros M. Exploring the effect of collective cultural attributes on covid-19-related public health outcomes. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:884. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese R.J., Kam C. University of Michigan Press; 2009. Modeling and Interpreting Interactive Hypotheses in Regression Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B.L., Tugade M.M., Waugh C.E., Larkin G.R. What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003;84(2):365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey C.B., Chen C., Presidente G. Democracy, culture, and contagion: political regimes and countries responsiveness to covid-19. Covid Economics. 2020;18:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A. The dark side of conscientiousness. Psychology. 2017;8(11):1879–1893. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber A.S., Huber G.A., Doherty D., Dowling C.M. The big five personality traits in the political arena. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2011;14:265–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling S.D., Rentfrow P.J., Swann W.B., Jr. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Pers. 2003;37(6):504–528. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano W.G., Habashi M.M., Sheese B.E., Tobin R.M. Agreeableness, empathy, and helping: a person× situation perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007;93(4):583. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein F.I. The impact of personality on the end of the Cold War: a counterfactual analysis. Polit. Psychol. 1998;19(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekara A., Dahanayake P., Attanayake C., Bertone S. Paternalistic leadership as a double-edged sword: analysis of the Sri Lankan President's response to the COVID-19 crisis. Leadership. 2022 doi: 10.1177/17427150221083784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Angrist N., Cameron-Blake E., Hallas L., Kira B., Majumdar S., Webster S. 2020. Variation in Government Responses to COVID-19.www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/covidtracker Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T.…Majumdar S. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nat. Human Behav. 2021;5(4):529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanania R. The personalities of politicians: a big five survey of American legislators. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2017;108:164–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbing M.V., Ritchie M., Anderson M.R. Personality and political discussion. Polit. Behav. 2011;33(4):601–624. [Google Scholar]

- Hills P., Argyle M. Emotional stability as a major dimension of happiness. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2001;31(8):1357–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Hochwarter W.A., Witt L.A., Kacmar K.M. Perceptions of organizational politics as a moderator of the relationship between consciousness and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000;85(3):472. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G., Hofstede G.J., Minkov M. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2010. Cultures and Organizations, Software of the Mind. Intercultural Cooperation and its Importance for Survival. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe L., Marks G., Schakel A.H., Chapman Osterkatz S., Niedzwiecki S., Shair-Rosenfield S. Volume I: Measuring Regional Authority. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2016. A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance. [Google Scholar]

- IMF . 2018. Central Government Debt.https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/CG_DEBT_GDP@GDD/CHN/FRA/DEU/ITA/JPN/GBR/USA (Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Campbell L.A., Gleason K.A., Adams R., Malcolm K.T. Interpersonal conflict, agreeableness, and personality development. J. Pers. 2003;71(6):1059–1086. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John O.P., Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 1999;2(1999):102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Joly J.K., Hofmans J., Loewen P. Personality and party ideology among politicians. A closer look at political elites from Canada and Belgium. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:552. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge T.A., Higgins C.A., Thoresen C.J., Barrick M.R. The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Person. Psychol. 1999;52(3):621–652. [Google Scholar]

- Kavakli K.C. Did populist leaders respond to the COVID-19 pandemic more slowly? Evidence from a Global Sample. 2020 https://covidcrisislab.unibocconi.eu/sites/default/files/media/attach/Kerim-Can-Kavakli.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley A.F., Noordewier T.G., Bergh R.G.V. Overstating and understating interaction results in international business research. J. World Bus. 2017;52(2):286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Koehn N. Simon and Schuster; 2017. Forged in Crisis: the Power of Courageous Leadership in Turbulent Times. [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld S.O., Patrick C.J., Benning S.D., Berg J., Sellbom M., Edens J.F. The role of fearless dominance in psychopathy: confusions, controversies, and clarifications. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2012;3(3):327–340. doi: 10.1037/a0026987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister I. In: The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Dalton R.J., Klingemann H.D., editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2007. The personalization of politics; pp. 571–588. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R., Costa P.T. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987;52(1):81. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R., John O.P. An introduction to the five‐factor model and its applications. J. Pers. 1992;60(2):175–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros K.E., Crayne M.P., Griffith J.A., Hardy J.H., III, Damadzic A. Leader sensemaking style in response to crisis: consequences and insights from the COVID-19 pandemic. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2022;187 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. The secret to Germany's COVID-19 success: Angela Merkel is a scientist. Atlantic. 2020;20 April https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/04/angela-merkel-germany-coronavirus-pandemic/610225/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Mkhondo R. 2020 3 May. How Covid-19 Has Exposed the Characters and Communication Skills of Some World Leaders.https://www.news24.com/news24/columnists/guestcolumn/opinion-how-covid-19-has-exposed-the-characters-and-communication-skills-of-some-world-leaders-20200503-2 News24. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Mondak J.J. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2010. Personality and the Foundations of Political Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Mondak J.J., Halperin K.D. A framework for the study of personality and political behaviour. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2008:335–362. [Google Scholar]

- Moshagen M., Thielmann I., Hilbig B.E., Zettler I. Meta-analytic investigations of the HEXACO personality inventory (-Revised) Z. für Psychol. 2019;227(3):186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde C. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Nai A. Disagreeable narcissists, extroverted psychopaths, and elections: a new dataset to measure the personality of candidates worldwide. Eur. Polit. Sci. 2019;18(2):309–334. [Google Scholar]

- Nai A., Maier J. Perceived personality and campaign style of hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2018;121:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nai A., Maier J. Can anyone be objective about Donald Trump? Assessing the personality of political figures. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties. 2021;31(3):283–308. [Google Scholar]

- Nai A., Martinez i Coma F. The personality of populists: provocateurs, charismatic leaders, or drunken dinner guests? W. Eur. Polit. 2019;42(7):1337–1367. [Google Scholar]

- Newman J.P. Reaction to punishment in extraverts and psychopaths: implications for the impulsive behavior of disinhibited individuals. J. Res. Pers. 1987;21(4):464–480. [Google Scholar]

- Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C.…Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int. J. Surg. 2020;78:185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen D., Davidson J. Hubris syndrome: an acquired personality disorder? A study of US Presidents and UK Prime Ministers over the last 100 years. Brain. 2009;132(5):1396–1406. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulejo M., Querubín P. Electoral concerns reduce restrictive measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Publ. Econ. 2021;198 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey A.J., Klingler J.D., Hollibaugh G.E., Jr. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2017. More than a Feeling: Personality, Polarization, and the Transformation of the US Congress. [Google Scholar]

- Riolli L., Savicki V., Cepani A. Resilience in the face of catastrophe: optimism, personality, and coping in the Kosovo crisis. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002;32(8):1604–1627. [Google Scholar]

- Rooduijn M., Van Kessel S., Froio C., Pirro A., De Lange S., Halikiopoulou D.…Taggart P. 2019. The PopuList: an Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenzer S.J., Faschingbauer T.R., Ones D.S. Assessing the US presidents using the revised NEO Personality Inventory. Assessment. 2000;7(4):403–419. doi: 10.1177/107319110000700408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saalfeld T., Kyriakopoulou K. In: The Political Representation of Immigrants and Minorities: Voters, Parties and Parliaments in Liberal Democracies. Bird K., Saalfeld T., Wüst A.M., editors. Routledge; London: 2010. Presence and behaviour: black and minority ethnic MPs in the British House of Commons; pp. 250–269. [Google Scholar]

- Savoie D.J. University of Toronto Press; Toronto: 2008. Court Government and the Collapse of Accountability in Canada and the United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher G., Zettler I. House of cards or west wing? self-reported hexaco traits of Danish politicians. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2019;141:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Scott C., Medeiros M. Personality and political careers: what personality types are likely to run for office and get elected? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2020;152 [Google Scholar]

- Seibert S.E., Kraimer M.L. The five-factor model of personality and career success. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001;58(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sidi Y., Harel O. The treatment of incomplete data: reporting, analysis, reproducibility, and replicability. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018;209:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvia P.J., Nusbaum E.C., Berg C., Martin C., O’Connor A. Openness to experience, plasticity, and creativity: Exploring lower-order, high-order, and interactive effects. J. Res. Pers. 2009;43(6):1087–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford M.S., Houston R.J., Mathias C.W., Villemarette-Pittman N.R., Helfritz L.E., Conklin S.M. Characterizing aggressive behavior. Assessment. 2003;10(2):183–190. doi: 10.1177/1073191103010002009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. Coronavirus brings out best (and worst) in world leaders. Politico. 2020, 25 March https://www.politico.eu/article/coronavirus-brings-out-best-and-worst-in-world-leaders/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasky M. This is a man-made disaster, and that man is Donald Trump. Daily Beast. 2020, 27 March https://www.thedailybeast.com/americas-coronavirus-response-is-a-man-made-disaster-and-that-man-is-donald-trump Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S. Informant reports: a cheap, fast, and easy method for personality assessment. J. Res. Pers. 2006;40(5):472–481. [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S. Who knows what about a person? The self–other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010;98(2):281. doi: 10.1037/a0017908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchione M., Caprara G.V. Personality determinants of political participation: the contribution of traits and self-efficacy beliefs. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2009;46(4):487–492. [Google Scholar]

- Visser B.A., Book A.S., Volk A.A. Is Hillary dishonest and Donald narcissistic? A HEXACO analysis of the presidential candidates' public personas. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2017;106:281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Walter A.S., Van der Eijk C. Measures of campaign negativity: comparing approaches and eliminating partisan bias. The International Journal of Press/Politics. 2019;24(3):363–382. [Google Scholar]

- Watts A.L., Lilienfeld S.O., Smith S.F., Miller J.D., Campbell W.K., Waldman I.D.…Faschingbauer T.J. The double-edged sword of grandiose narcissism: implications for successful and unsuccessful leadership among US presidents. Psychol. Sci. 2013;24(12):2379–2389. doi: 10.1177/0956797613491970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Who . 2020. Global Health Observatory Data Repository.https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.home Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank International tourism, receipts (% of total exports) 2018. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.RCPT.XP.ZS Retrieved from.

- Yong E. America is trapped in a pandemic spiral. Atlantic. 2020, 13 September https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/09/pandemic-intuition-nightmare-spiral-winter/616204/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and codes are available for replication at the following anonymous OSF repository: https://osf.io/rb2zq/.