Abstract

The present study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of Schistosoma spindale infection in domestic ruminants in Krishna district, Andhra Pradesh by coprological and necropsy examination. Examination of 177 buffaloes, 283 sheep and 166 goats faecal samples (n = 626) revealed 2.25, 2.82 and 1.80% of S. spindale infection, respectively. Necropsy examination of 21 buffaloes, 185 sheep and 217 goats revealed 14.2, 1.08 and 3.68% of S. spindale infection, respectively. Overall, microscopic examination of faecal smears revealed 2.39% (n = 15) prevalence of S. spindale infection in ruminants in the study area, while 3.07% (n = 13) of ruminants were found to be positive for S. spindale during postmortem examination. Adult worms collected from the mesenteric veins were processed and identified as S. spindale. Grossly, the infected livers were found with petechial haemorrhages, cirrhotic changes and pinpoint granulomas in parenchymatous tissue. Histological sections of livers revealed microgranulomas with infiltration of mononuclears, eosinophils and fibroblast cells surrounding the Schistosome ova. The intestinal mucosa was thickened, edematous and haemorrhagic with copious mucous exudates. Cut section of infected intestines revealed severe inflammatory reactions in the mucosa and sub mucosa and granulomatous changes surrounding the Schistosoma eggs.

Keywords: Buffalo, Goat, Histopathology, Prevalence, Schistosoma spindale, Sheep

Introduction

Schistosomosis caused by Schistosoma spp. is a widespread trematode infection both in man and animals, the most common species that occur in India are S. nasale, S. spindale, S. indicum and S. incognitum. Among these, S. spindale is usually found in the mesenteric venules of domestic ruminants and is responsible for acute intestinal and chronic hepatic schistosomosis (Agarwal and Southgate 2000). Schistosoma spindale infection is characterized by frequent diarrhoea with blood and mucous, colic, weight loss and weakness in animals and form egg granulomas in the liver and intestines of affected animals (Frasen et al. 1990) and is reported from different parts of the world. The disease primarily runs in a chronic form the symptoms in most animals are undistinguished from other debilitating infections. The high prevalence of chronic schistosomosis causes significant loss to the herd in connection with morbidity and mortality, liver condemnation, reduced productivity and increased susceptibility to other infectious agents (De Bont and Vercruysse 1990). In India, the disease is considered a fifth major helminthosis in domestic animals (Cherian and D’ Souza 2009) as it causes substantial economic losses in the form of chronic and wasting illnesses in livestock. Routine diagnosis of the infection relies primarily on clinical symptoms and faecal examination, which are ineffective and underestimate the actual prevalence status of schistosomosis. Worm counts from mesentery estimate the true prevalence of infection (Ravindran et al. 2007). There is a lack of information on schistosomosis in ruminants in Andhra Pradesh, though is reported in different parts of India (Jeyathilakan et al. 2008; Lakshmanan et al. 2011; Agarwal et al. 2013; Pawar et al. 2018). Hence, the present study is aimed to determine the prevalence of S. spindale infection in domestic ruminants in Krishna district, Andhra Pradesh by faecal examination and postmortem examination along with a pathomorphological description of the disease in the liver and intestines of slaughtered ruminants.

Materials and methods

The present work doesn’t involve any human and or animals. Material was collected from slaughtered animals and hence does not necessitate ethical approval. Faecal samples from 177 buffaloes, 283 sheep, and 166 goats (n = 626) were collected from the Livestock farm complex, NTR College of Veterinary Science, Gannavaram, Veterinary dispensaries, and local forms in and around Krishna district, Andhra Pradesh during the last four years (March 2017 to February 2021). Faecal samples were processed by sedimentation technique and morphometry of Schistosoma eggs was carried out (Soulsby 1987). In addition, mesenteries of 21 buffaloes, 185 sheep, and 217 goats (n = 423) were screened for the presence of adult blood flukes for the same period, which was collected from local slaughterhouses in the Krishna district. The different organs were carefully examined and palpated for the presence of any gross abnormality. The organs liver, and intestines infected with schistosomes were collected from slaughterhouses were kept on ice, and brought to the laboratory for further examination. The mesenteries with flukes were cut into small pieces, immersed in normal saline for 5–6 h and flukes were recovered by repeated sieving and washing steps. Flukes were subjected to borax carmine stain for species identification (Soulsby 1987). The representative tissue pieces were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed routinely for histopathological analysis (Luna 1968). Data obtained were classified according to age, sex, and season was analyzed statistically by the chi-square (x2) method (Petrie and Watson 2013).

Results and discussion

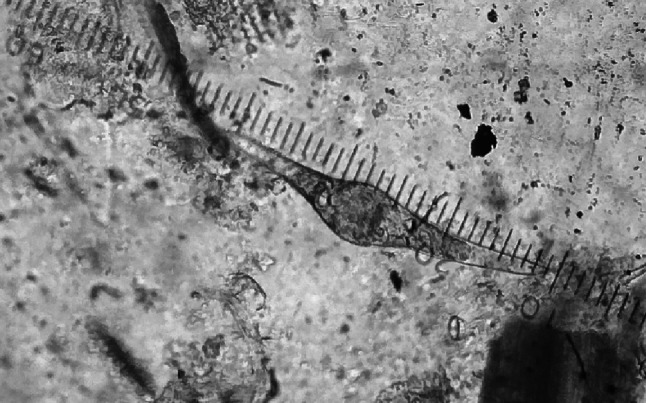

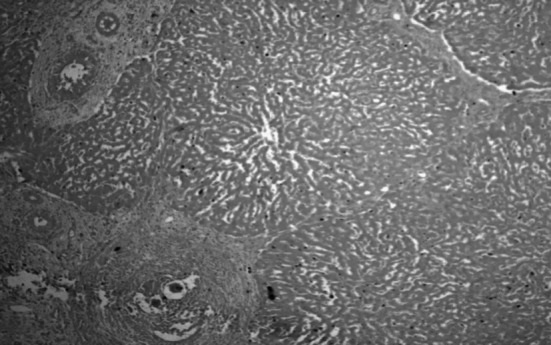

The prevalence rate of schistosomosis was analyzed by faecal sedimentation and postmortem examination from all collected animals (Table 1). The overall prevalence of schistosomosis by faecal sedimentation examination revealed 2.39% (n = 15), whereas postmortem examination revealed 3.07% (n = 13). The Schistosoma eggs were confirmed as S. spindale based on morphological features of a more elongated spindle shape body with a terminal spine and flattened at one side (Fig. 1). The size of the eggs in buffaloes, sheep, and goats were 332.62 ± 0.56/70.89 ± 5.78, 297 ± 8.02/65.58 ± 5.05, and 291.54 ± 10.87/68.08 ± 4.13 μm, respectively and was in accordance with the descriptions of Soulsby (1987), Bhoyar et al. (2012) and Tan et al. (2015). Flukes collected from mesenteric veins and livers were identified as S. spindale by the presence of smooth cuticles and few testes behind the ventral sucker in males similarly, spindle-shaped typical eggs with terminal spines in the uterus of female flukes (Figs. 2, 3 and 4).

Table 1.

Prevalence of S. spindale infection by coprological and postmortem examination

| Coprological examination | Chi-square | Postmortem examination | Chi-square | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of samples screened | No. of samples positive | No. of samples screened | Positive | |||

| Species | 0.4847NS |

11.60** (df.P < 0.01) |

||||

| Buffaloes | 177 | 4(2.25) | 21 | 3(14.2) | ||

| Sheep | 283 | 8(2.82) | 185 | 2(1.08) | ||

| Goat | 166 | 3(1.80) | 217 | 8(3.68) | ||

| Age |

4.66* (df.P < 0.05) |

0.25NS | ||||

| Young(< 1 year) | 407 | 6(1.47) | 318 | 9(2.83) | ||

| Adult(> 1 year) | 219 | 9(4.10) | 105 | 4(3.80) | ||

| Sex | 0.84NS | 0.20 NS | ||||

| Male | 388 | 11(2.83) | 374 | 12(3.20) | ||

| Female | 238 | 4(1.68) | 49 | 1(2.04) | ||

| Season | 1.39 NS | 1.48 NS | ||||

| Summer | 175 | 3(1.71) | 94 | 2(2.12) | ||

| Monsoon | 205 | 7(3.41) | 131 | 6(4.58) | ||

| Winter | 246 | 5(2.03) | 198 | 5(2.52) | ||

| Total samples screened | 626 | 15(2.39) | 423 | 13(3.07) | ||

Figures in parenthesis indicate percent P* < 0.05; P* < 0.01

Fig. 1.

S. spindale egg with terminal spine in faecal smear (10X)

Fig. 2.

Adult schistosomes in mesenteric veins

Fig. 3.

Adult male S. spindale with smooth cuticle 4X

Fig. 4.

Adult female S. spindale gravid uterus with eggs 40 X

Faecal smear examination revealed lower infection rates in comparison with the postmortem examination strengthens that the farmer technique is less sensitive in the detection of S. spindale infection as eggs in the faeces of affected animals were masked by high mucus content and rapid hatching of Schistosoma eggs that may happen during the sedimentation process before the sample is examined on the slide, thus are often misdiagnosed. While comparing the efficacy of direct faecal smear, formal ether technique, alkaline digestion and miracidial hatching technique in the diagnosis of ovine schistosomosis by Cherian and D’Souza (2009) opined that faecal smear examination failed to detect any of the tested samples positive. It is well known fact that the flukes are intermittent egg layers and not all the eggs of schistosomes are excreted in the faces, half of the eggs remains in the circulation and are subsequently trapped in tissues (Ross et al. 2002; Defersa and Belete 2018). Nevertheless, with post-mortem examination, adult flukes can be easily detected in the mesenteric vein or liver. Hence, prevalence can be underestimated when exclusively based on faecal examination. The prevalence of Schistosoma in cattle was lower on farms and higher in slaughterhouse studies in Cote d Ivoire, West Africa (Kouadio et al. 2020). These observations should be interpreted with caution because the two populations of animals differ in important ways, and the animals screened were not from the exact same places. Therefore, results from farms could not be compared to those from abattoirs as it is opined by Kouadio et al. (2020).

Overall, the prevalence of schistosomosis in ruminants in the study area was relatively low compared to the prevalence reports in other parts of the country (Lakshmanan et al. 2011; Agarwal et al. 2013) and in other Asian countries (Islam et al. 2011; Tan et al. 2015). The variations in the prevalence rates might be due to the difference in diagnostic methods adopted in addition to the climatic and geographical factors which influence the propagation and survival of parasite. In accordance to the present results, Cherian and D’Souza (2009) recorded very low (0.5%) level of S. spindale infection in sheep in Karanataka. Necropsy examination revealed higher prevalence of S. spindale infection in buffaloes (x2 = 11.60, df = 1, P < 0.01)) compared to that of goats and sheep. Similarly, Ravindran et al. (2007), Jeyathilakan et al. (2008) and Agrawal et al. (2013) also reported higher prevalence in buffaloes than in goats in Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Madhya Pradesh, respectively. The prevalence of S. spindale was higher in sheep than in buffaloes and goats in faecal examination, but no significant (P > 0.05) difference was observed. Differences in the prevalence rate of infection in different hosts might be due to the change in behaviour and feeding system of domesticated animals, managemental practices and grazing patterns. Buffaloes are the natural hosts for the S. spindale infection and the disease runs in chronic form. Further, buffaloes graze away from the villages and consume water from rivers and dams. Goats and sheep, on the other hand, frequently graze near villages and drink water provided by farmers. This minimizes the danger of Schistosoma infection in goats and sheep by reducing contact with contaminated water (Kouadio et al. 2020).

The prevalence of S. spindale infection was high in adult animals than in young animals in faecal examination (x2 = 4.66, df = 1, P < 0.05) and necropsy examination (P > 0.05) in agreement with the previous reports (Tan et al. 2015; Assfaw and Samuel 2017; Pawar et al. 2018). The reason could be due to frequent exposure of older animals to snail-infested water and pastures besides those older animals have selective grazing behavior as move deep into the water sources to get lustrous pastures. The prevalence of S. spindale infection was non-significantly (P > 0.05) high in males than in females in faecal examination and necropsy examination (Assfaw and Samuel 2017), which could be attributed to the fact that the males were more often slaughtered for consumption, while the females were left for milk production and breeding. The Season was not associated with S. spindale infection in ruminants in the study area though the prevalence was high in monsoon season (P > 0.05) (Jeyathilakan et al. 2008; Islam et al. 2011).

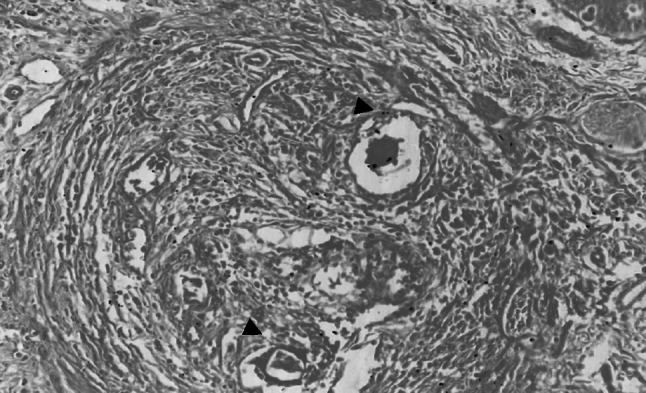

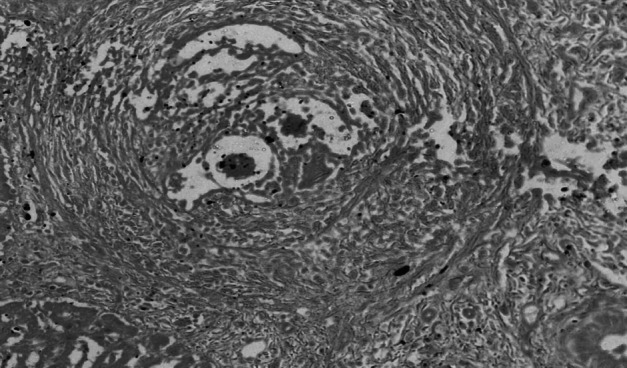

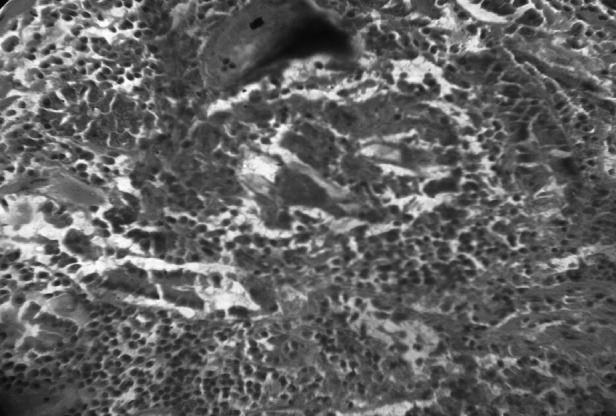

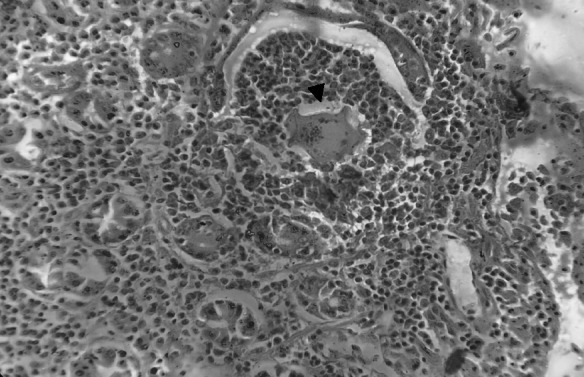

Grossly the infected livers did not reveal any peculiar pathological changes in both small and large ruminants except mild lesions like enlarged livers, degenerative changes, few whitish foci and these findings were in accordance with the previous descriptions (Frasen et al. 1990; Cherian et al. 2010). Whereas, intestines revealed notable gross lesions like thickened hyperemic mucosa, petechial haemorrages with copious mucous exudates and engorged superficial blood vessels which were similar with the earlier reports (Figs. 5 and 6) (Hussein et al. 1975; Hossain et al. 2015). Histopathologically Schistosoma egg granulomas were evident in both liver and intestine tissues. The liver sections manifested granulomas in portal veins, periportal areas in the subcapsular regions and with occasional occurance in intra parenchymatous tissues were in agreement with the previous studies (Cherian et al. 2010) (Fig. 7). The granulomas were commonly attached to adjoining portal tracts and to the liver capsule by slender connective tissue trabeculae, giving lesions of ‘septal fibrosis’. Each granuloma contained parasite ova of either viable or degenerating being either engulfed or encircled by giant cells and surrounded by eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, epithelioid cells and fibroblasts peripherally (Fig. 8). Some granulomas however, were concentrically fibrosed, presenting an onion-peel appearance (Fig. 9). Vascular changes like thickening of portal tracts, focal phlebitis along with prominent inflammatory reaction and increased fibrous connective tissue proliferation was observed (Fig. 10). Proliferative endophlebitis along with subintimal and perivascular eosinophilic infiltration and often occlusion by granulomas or eggs were noticed in small blood vessels. In addition, marked hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the medial tunica, intimal proliferation and fibrosis with severe subintimal eosinophilic infiltration were similar to the observations of Frasen et al. (1990). Larger veins revealed villous projections of endothelium obliterating the lumen and partly organized thrombosis of the portal veins giving laminated appearance and contained schistosomes, haemosiderin pigment and parasitic eggs in few cases. The affected veins were extensively infiltrated by eosinophils, and surrounded by multiple, thin-walled vascular neoformations or ‘angiomatoids’. The hepatocytes adjacent to the granulomas showed degenerative changes, necrosis and inflammatory reaction. Small to medium sized encapsulated epitheloid cell granulomas, were present diffusely throughout the liver parenchyma and other lesions in focal biliary proliferation with globule leucocytes infiltration in large bile ducts, sinusoidal dilatation, congestion and hemorrhages in sinusoidal spaces and deposition of blackish schistosoma pigment in the walls of portal veins were observed in few cases. The current findings were identical to the earlier descriptions of Singh et al. (2000) and Cherian et al. (2010).

Fig. 5.

Small intestine with severe hyperemia in serosa with tortuous and thick blood vessels occluded by thrombi

Fig. 6.

Intestinal mucosa of cattle with mucous exudates and haemorrhages

Fig. 7.

Liver showing granulomas in portal areas and thickened portal tract H & E 100X

Fig. 8.

Liver revealing cut section of parasitic ova in the centre of granuloma surrounded by inflammatory cells H & E 100X

Fig. 9.

Ggranuloma in liver with parasite ova in the centre surrounded by inflammatory cells and concentrically arranged fibroblasts giving onion peel appearance H&E 400X

Fig. 10.

Thickened and prominent portal areas due to inflammatory reaction and increased fibrous connective tissue proliferation H & E 100X

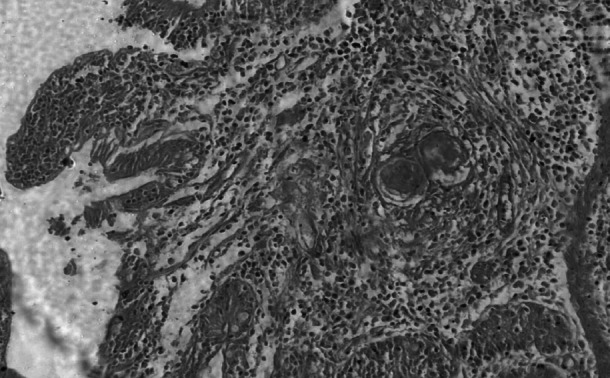

Features of intestinal lesions were in consonance with observations of Chandra et al. (2003) such as mild to severe edema, hyperaemia with focal petechial haemorrhages in mucosa with moderate to intense eosinophilic infiltration in sub mucosa of ileo-caecal areas. All the infected intestines showed presence of few granulomas along with superficial epithelial desquamation, increased goblet cells, marked thickening and hyaline necrosis of the intestinal arterioles (Fig. 11). Adult parasites were detected within the thickened serosal veins along with perivascular infiltration of eosinophils, neutrophils and plasma cells in some animals. (Figures 12 and 13). A few blood vessels unveiled endothelial cell proliferation, subendothelial granulomatous reaction and finger-like protrusions within their lumina accompanied by Phlebitis and arteritis. Usually granulomas were observed in submucosa and serosa, comprised of necrotic centers with parasites or their remnants, surrounded by large numbers of lymphocytes, eosinophils, epitheloid cells and gaint cells (Fig. 14). The current histopathological observations in affected livers and intestines were related to the earlier descriptions except that splendore-hoeppli reaction explained by Frasen et al. (1990) and hepatic nodular cirrhosis by Sobrero (1958). The lesions in Schistosoma infected animals were mainly associated with deposition of eggs in visceral organs invaraiably in the liver and intestines when compared to other tissues.

Fig. 11.

Intestine with severe edema, focal petechiae in mucosa with moderate to intense eosinophilic infiltration and granuloma with cut section of parasitic ova in its center. H & E 100X

Fig. 12.

Intestine reveals thickened walls of infected blood vessels, surrounded by polymorphonuclear leucocytes. H & E 100X

Fig. 13.

Intestine with adult parasites within the veins along with perivascular infiltration of eosinophils and neutrophils. H & E100X

Fig. 14.

Granuloma in submucosa comprised of necrotic centres with parasites, surrounded by lymphocytes, eosinophils, epitheloid cells and gaint cells with cryptal degeneration. H & E 100X

Conclusions

The present results revealed that schistosomosis is prevalent in ruminants in the study area being high in buffaloes than in small ruminants, and disease can be under estimated when exclusively based on faecal examination. Necropsy studies communicates that the schistosomes severely damage the liver and intestines, further causes significant herd loss in the form of mortality and morbidity. Further, there is a need for large-scale studies involving advanced immunological and molecular techniques to obtain precise epidemiological data on schistosomes.

Aknowledgements

The author is thankful to the Dean, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Sri Venkateswara Veterinary University, Tirupati for providing necessary facilities to carry out this research work and also Dr. K. Sudhakar, Dept. of. Animal Genetics and Breeding for statistical analysis of the data.

Funding

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

All authors informed their consent for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agarwal MC. Schistosomosis: an under estimated problem in animals in South Asia. World Animal Rev. 1999;92:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal MC. Schistosomes and Schistosomiasis in South Asia. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal MC, Southgate VR. Schistosoma spindale and bovine schistosomosis. J Vet Par. 2000;14:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal V, Garg UK, Shukla MK, Das G. Prevalence of Schistosoma spindale in ruminants in Malwa region of Madhya Pradesh. Ruminant Sci. 2013;2:73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Assfaw F, Samuel D. Prevalence of small ruminants schistosomes and its associated risk factors in Mecha district, North eastern Etiopia. J Animla Feed Sci. 2017;7:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Associated Risk Factors for its Occurrence among Cattle in the North Gulf of Lake Tana, Northwest Ethiopia.J Vet Med Anim Health 2:112

- Bedarkar SN, Narladkar BW, Deshpande PD. Seasonal prevalence of snail fluke infections in ruminants of Marathwada region. J Vet Par. 2000;1:51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bhoyar R, Sivanand SK, Halmandge SC, Vivek RK, Patil NA. Caprine schistosomiosis and its therapeutic management. Intas Polivet. 2012;13:79–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra D, Singh KP, Singh R, Samantha S, Rasool A. Schistosomosis in sheep flocks in southern states of India. Indian J Vet Pathol. 2003;27:93–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cherian S, D’Souza PE. Coprological diagnosis of ovine schistosomosis by different laboratory techniques. Vet World. 2009;2:271–273. [Google Scholar]

- Cherian S, D’Souza PE. Prevalence of Schistosomosis in sheep in Karnataka. J Vet Par. 2009;23:93–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cherian S, D’Souza PE, Renuka Prasad C, Suguna R (2010) Histopathological observations in ovine schistosomosis. J Vet Par 24:2010

- De Bont J, Vecruysee J. Schistosomiasis in cattle. Adv Parasitol. 1998;41:285–263. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(08)60426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defersha T, Belete BA. The neglected infectious disease. Prevalence and Bovine Schistosomiasis: Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors for its Occurrence among Cattle in the North Gulf of Lake Tana, Northwest Ethiopia. J Vet Med Anim Health. 2018;2:112. [Google Scholar]

- Frasen J, De Bont J, Vercruysse J, Van Aken D, Southgate VR, Rollinson D. Pathology of natural infections of Schistosoma spindale montgomery,1906, in Cattle. J Comp Pathol. 1990;103:447–455. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9975(08)80032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain MS, Begum N, Rima UK, Dey AR, Khan AH. Morphologic and molecular investigation of schistosomes from the mesenteric vein of slaughtered cattle. IOSR J Agric Vet Sci. 2015;8:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein MF, Tartour G, Imbabi SE, Ali KE. The pathology of naturally-occurring bovine schistosomiasis in the Sudan. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1975;69:217–225. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1975.11687004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MN, Begum N, Alam MZ, Mamun MAA. Epidemiology of intestinal schistosomiasis in ruminants of Bangladesh. J Bangladesh Agril Univ. 2011;9:221–228. doi: 10.3329/jbau.v9i2.10990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyathilakan N, Bhaskaran R, Latha, Abdul Basith S. Seasonal prevalence of Schistosoma spindale in ruminants at Chennai. Tamilnadu J Vet Ani Sci. 2008;4:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kouadio JN, Giovanoli Evack J, Achi LY. Prevalence and distribution of livestock schistosomiasis and fascioliasis in Cote d Ivoire: results from a cross- sectional survey. BMC Vet Res. 2020;16:446. doi: 10.1186/s12917-020-02667-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan B, Rauoof A, Fawaz M, Subramanian H. Abattoir survey of Schistosoma spindale infection in Thrissur. J Vet Anim Sci. 2011;42:53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Luna LG. Manual of Histologic staining methods of the armed forces institute of Pathology. 3. New York: McGraw- Hill; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Pawar PD, Singla LD, Paramjit Kaur, Bal MS. Prevalence and associated host factors of caprine and bovine Schistosomosis in Punjab India. Ruminant Sci. 2018;7:261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, Watson P. Statistics for veterinary and animal science. 1. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2013. pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran R, Lakshmanan B, Ravishankar C, Subrmanian H. Visceral schistosomiasis among domestic ruminants slaughtered in Wayanad, South India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Publ Health. 2007;38:1008–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, Olds GR, Li Y. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:12–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Chandra D, Rathore BS, Singh KP, Malhotra ML. Investigation of mortality in Cattle and Buffaloes with particular reference to hepatic schistosomosis in Cattle. Indian J Vet Pathol. 2000;24:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrero R. Alterazioni del fegato nella Schistosomiasis dei bovini Somali. Rev sci parasitol. 1958;19:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby EJL (1987) Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals, 7th edn. Bailliere, Lindall, pp 660

- Sumanth S, D’Souza PE, Jagannath MS. A study of nasal and visceral schistosomosis in cattle slaughtered at an abattoir in Bangalore, South India. Rev sci tech. 2004;23:937–942. doi: 10.20506/rst.23.3.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan TK, Low VL, Lee SC, Panchadcharam C, Tay ST, Ngui R, Bathmanaban P, Kho KL, Koh FX, Harma RS, Jaafar T, Nizam QN, Lim YA. Detection of Schistosoma spindale ova and associated risk factors among Malasian cattle through coprological survey. J Vet Res. 2015;2:63–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]