Abstract

Pentatrichomonas hominis (P. hominis) is a large intestinal flagellated protozoan infecting humans. Little is known about the epidemiology of P.hominis in Egypt, its association with gastrointestinal symptoms and the co-infection with other parasites. Demographic and clinical data were collected from 180 school-aged children. Parasitological examination of fecal samples was done using direct wet mount, formalin ethyl-acetate, Kato–Katz and cultivation on Jones’ medium to detect P. hominis and associated parasitic infection. The diagnosis of P. hominis was confirmed using Giemsa stain and scanning electron microscopy. The prevalence of P. hominis was 13.8% (25 out of 180 children). The prevalence of parasitic co-infection was significantly higher in P. hominis infected (84%, 21 participants) than in non-infected children (56%, 87 participants). The presence of abdominal pain and diarrhea in P. hominis infected children was higher than in non-infected children (84% and 32% vs. 76% and 18%), respectively. The difference was not statistically significant. This is the first report of P. hominis in Egypt. The significant association between P. hominis and other intestinal parasites need more investigations. Further studies are needed to understand the epidemiology and pathogenicity of P. hominis.

Keywords: Pentatrichomonas hominis, Intestinal parasites, Culture, Co-infection

Introduction

Human trichomonads include four species (Pentatrichomonas hominis, Dientamoeba fragilis, Trichomonas tenax and Trichomonas vaginalis). One of them, T. vaginalis is potentially pathogenic to human. However, previous studies linked D. fragilis with gastrointestinal (GIT) symptoms and irritable bowel syndrome (Girginkardeşler et al. 2003; Stark et al. 2016). Trichomonas tenax may play a role in periodontitis as it synthesis enzymes that might contribute to damage periodontal tissues (Bisson et al. 2019). Pentatrichomonas hominis was reported as one of GIT commensals. Recently it has been recognized as one of the parasites causing diarrhea with a potential zoonotic transmission (Meloni et al. 2011; Bastos et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2019). Pentatrichomonas hominis doesn’t have a cystic form and the only form of this parasite is the fragile trophozoite that can’t exist for prolonged period in the environment (Romatowski 2000). It may be feco-orally transmitted through ingestion of the trophozoite form (Bastos et al. 2018). Pentatrichomonas hominis was reported in many animals as cats (17.65%), pet dogs (31.4%), pigs (7.8%), cattle (5.45%), and goats (0.3%) (Li et al. 2018a, b; Mahittikorn et al. 2021). The prevalence of P. hominis among dogs and cats with diarrhea was higher than those without diarrhea (Li et al. 2016a, b; Bastos et al. 2018). In rats, the pathogenicity of P. hominis was reported after splenectomy or immunosuppression (Chomicz et al. 2009).

In human, P. hominis was previously reported and it may be linked to gastrointestinal disturbances and irritable bowel syndrome (Cheng-Rong et al. 1990; Meloni et al. 2011). Chronic P. hominis infection in children can cause nutritional problems (Chomicz et al. 2009). It may be also associated with cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (Zhang et al. 2019).

Diagnosis of P. hominis can be done through direct microscopic examination, fecal culture and molecular techniques. Molecular techniques are useful in differentiating trichomonads species found in animal feces as Trichomonas gallinae in pigeons and Trichomonas foetus in cats (Bastos et al. 2018). Fecal culture needs rapid trophozoite cultivation. Permanently stained smears prepared from faecal culture is a sensitive detection method that yields clear field for proper morphologic identification. However, false negative results may be obtained if cultivation was delayed (Santos et al. 2015a, b), c. Pentatrichomonas hominis is not a fastidious organism that can grow on different media like Ringer's solution containing 10% horse serum (Hegner et al. 1936; Kamaruddin et al. 2014), Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (inorganic salts supplemented with glucose) (Dos Santos et al. 2015a, b, c), Pham medium (mixture of phosphate buffer solution and distilled water and MSF base) (Chomicz et al.2009). Based on previous observation (not published) P.hominis can grow on Jones’ medium.

In Egypt, there is no data about the prevalence of P. hominis. The aim of the present study is to detect the prevalence of P. hominis and the clinical and parasitological association between P. hominis and other intestinal parasitic infections in Egyptian children.

Materials and methods

A cross sectional study was conducted in a rural community in Kafrelsheikh from April 2021 to October 2021. A standardized questionnaire was used to record demographic data (age and gender), clinical signs and symptoms. Participants were requested to submit fresh stool specimens free from water and urine. In the field, stool samples were divided into three parts; the first part (about 50 mg) was immediately cultured in 5 ml Jones’ medium enriched with 10% horse serum (Jones 1946), the second part was preserved in formalin ethyl acetate, the third part was conserved to be examined by direct wet mount (within two hours) and Kato–Katz. Stool samples were examined at the Parasitology Department, Medical Research Institute (MRI), Alexandria University. All culture tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 3 days and examined daily using light microscopy. Positive samples were further processed for Giemsa staining and electron microscopy. Horse serum was kindly supplied by the Laboratory of Parasitology, Medical Research Institute, Alexandria, Egypt.

Staining

Thin smears were prepared from cultured P. hominis then air-dried, fixed and stained with Giemsa stain to confirm the diagnosis (Romatowski 2000).

Electron microscopy

Cultured samples were centrifuged at 2000×g for 10 min using phosphate buffered saline (PBS). After centrifugation, the sediment was fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, washed with PBS and fixed in 1% Osmium tetroxide. The samples were dehydrated in alcohol and critical-point-dried using CO2. Finally, gold was used to coat the samples which were then examined using scanning electron microscope (Romatowski 2000; Li et al. 2014a, b).

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, IBM SPSS software suite version 20.0 was used. Chi-square test was used to compare the study findings. The significance level was set at 5% level.

Results

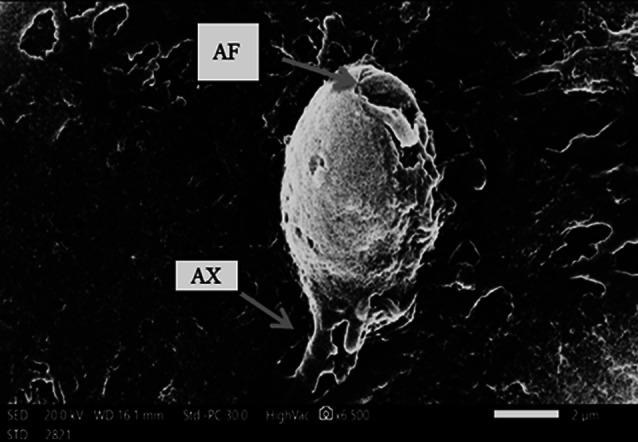

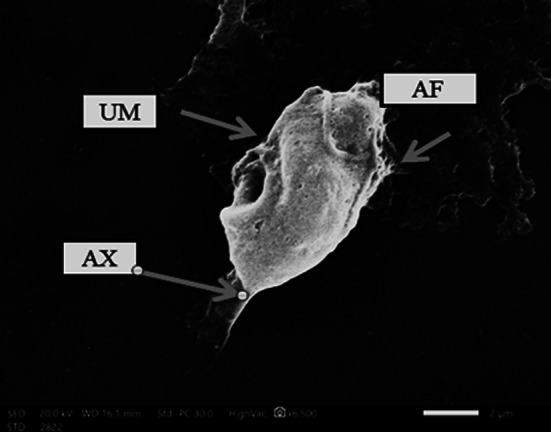

The overall prevalence of P. hominis was 13.8% (25 out of 180 children) using direct wet mount, formalin ethyl acetate and culture technique. P. hominis trophozoite was identified by its characteristic shape and motility. Diagnosis of P. hominis was confirmed using Giemsa stain and scanning electron microscopy. The trophozoite was 10 μm × 5 μm, with an undulating membrane which has about 3–5 undulations. There were five anterior flagella and one recurrent flagellum (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Morphology of P. hominis trophozoite under scanning electron microscopy

Fig. 2.

The trophozoite has an undulating membrane (UM), four anterior flagella (AF) and an axostyle (AX)

The participant’s age ranged from 3 to 15 years with a mean of 9.5 ± 1.8 years in P. hominis infected children and 10 ± 1.5 years in non-infected children. There was no significant difference between infected and non-infected children regarding age. There was no significant difference between males and females in P. hominis infected (40%and 60%) and non-infected children (41.8% and 58.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age and gender difference in P. hominis infected and non-infected children

| P. hominis infection | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Positive (n = 25) | Negative (n = 155) |

| Gender: N. (%) | ||

| Male | 10 (40) | 65 (42) |

| Female | 15 (60) | 90 (58) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 9.5 ± 1.8 | 10 ± 1.5 |

Infection with intestinal parasites other than P. hominis was detected in 21 out of 25 P. hominis infected children (84%) and in 87 out of 155 P. hominis negative children (56%). The difference was statistically significant (p-value = 0.008) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The association between P. hominis infection and other parasitic infection

| Associated parasites | P. hominis infection | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 25) | Negative (n = 155) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Blastocystis sp. | 16 | 64 | 43 | 27.7 | < 0.001* |

| Giardia lamblia | 6 | 24 | 11 | 7 | 0.007* |

| Schistosoma mansoni | 3 | 12 | 20 | 12.9 | 0.900 |

| Hymenolepis nana | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.137 |

| Ascaris lumbrecoides | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.2 | 1 |

| Total | 21 | 84 | 87 | 56.1 | 0.008* |

*p value < 0.05 is significant

Blastocystis sp. was the most frequent parasite in P. hominis infected (64%) and a non-infected child (27.7%) but it was more evident in infected children. The difference was statistically significant (p-value = 0.003) (Table 2).

The other associated parasites were Giardia lamblia, Schistosoma mansoni and Hymenolepis nana in the following frequencies of 24%, 4% and 4% in P. hominis infected children and 7%, 13% and 0.5% in non-infected children. P. hominis showed a significant association with Giardia lamblia (p-value = 0.007) (Table 2).

Including any parasite other than P. hominis.

Fisher exact test.

Regarding abdominal pain, it was reported in 21 out of 25 P. hominis positive children (84%) while 118 out of 155 P. hominis negative participants (76.1%) complained of abdominal pain. The difference was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.3) (Table 3). Diarrhea was present in eight out of 25 P. hominis positive children (32%) while 28 out of 155 (18%) of P. hominis negative participants had diarrhea. The difference was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.1) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The association between P. hominis infection and GIT symptoms

| GIT symptoms | P.hominis infection | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes = 25 | No = 155 | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Pain | 21 | 84 | 118 | 76.1 | 0.383 |

| Diarrhea | 8 | 32 | 28 | 18 | 0.105 |

Among the 25 children infected with P. hominis there were 19 children co-infected with other intestinal parasites and six children weren’t co-infected with other intestinal parasites. Out of the 19 children co-infected with other intestinal parasites, 15 (79%) complained of abdominal pain and/or diarrhea. All P. hominis infected children, who weren’t co-infected with other intestinal parasites, complained of abdominal pain and/or diarrhea (six out of six children). The difference was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.5) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of P. hominis infected children according to the presence of abdominal pain and/or diarrhea and co-infection with other intestinal parasites (n = 25)

| Co-infection with other parasites | Abdominal pain and/or diarrhea | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Yes | 15 | 79 | 4 | 21 | FEp = 0.5404 |

| No | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

Discussion

Pentatrichomonas hominis is one of trichomonad species that colonize the GIT of human and many animals. Generally, P. hominis is underestimated in human. In the present study, the prevalence of P. hominis was 13.8% among school aged children in Egypt. P. hominis was found in 1% of children in Australia, two out of 50 children in China and in three participants out of 964 examined females in Zambia (Meloni et al. 1993; Crucitti et al. 2010; Li et al. 2016a, b).

There was no significant sex-related difference in P. hominis infection. A previous study in china found no association between gender and P. hominis infection however, the infection rate was higher in children than adult (Li et al. 2016a, b).

In the present study, abdominal pain and diarrhea were present in 84% and 32% in P. hominis infected children compared to 76% and 18% in non-infected children. Although GIT symptoms were more evident in infected children than non-infected children, the difference was not statistically significant. All P. hominis infected children who weren’t co-infected with other intestinal parasites complained of abdominal pain and/or diarrhea (six out of six children). The presence of abdominal pain and/or diarrhea was reported in 79% P. hominis infected children co-infected with other intestinal parasites (15 out of 16).

The association between P. hominis infection and diarrhea was reported in animals and human (Cheng-Rong et al. 1990; Meloni et al. 2011; Bastos et al. 2018). It was found in two patients with GIT troubles and in 3.6% of children complaining of diarrhea in China (Cheng-Rong et al. 1990; Meloni et al. 2011). Pentatrichomonas hominis trophozoite was isolated from the feces and lung exudate of 28 year-old woman with diarrhea and quadriplegia in Thailand (Jongwutiwes et al. 2000).A study conducted in China reported that the prevalence of P. hominis was 41.54% in cancer patients and 9.15% in non-infected children. In animals, several studies reported P. hominis in stool samples of domestic kittens with diarrhea (Romatowski 2000; Dos Santos et al. 2015a, b, c; Bastos et al. 2018).

The presence of other parasitic infection was significantly more common in P. hominis infected children (76%) than non-infected children (56%). The difference was statistically significant (p-value = 0. 008). Considering that both infected children and non-infected children share the same environmental conditions, this result may indicate that infected children might be exposed to higher risks to get parasitic infections than non-infected children. Further studies are needed to understand the effect of P. hominis on GIT microbiota.

Coinfection with Blastocystis sp. was significantly more common in P. hominis infected compared to non-infected children (64% vs. 27.7%). The difference was statistically significant (p-value = 0.003). A previous study in China reported that the prevalence of Blastocystis sp. and P. hominis was the same (0.3%, 2/781) in goats (Li et al. 2018a, b). The reporting of P. hominis and Blastocystis sp. isolated from different animal species and their close phylogenetic relationship to human isolates indicates that both parasites may be zoonotically transmitted between humans and other animal hosts (Li et al. 2016a, b, 2018a, b; Abdo et al. 2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Hend Aly El-Taweel at parasitology department, Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University, Egypt for her excellent technical assistance.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Research Institute (MRI), Alexandria University (IORG 0008812). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. All procedures performed in study were in accordance with the ethical standards of Medical Research Institute (MRI), Alexandria University.

Consent to participate

Verbal consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Verbal consent was obtained from all participants. A written informed consent was taken from all the study participants and children’s guardians after explanation of the study purpose.

Study limitation

Although there is no data about the prevalence of P. hominis in Egypt, sample size should be calculated. Direct wet mount examination should be done within 30 min to detect the trophozoite. Jones’ medium should be compared with another media for quality control.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdo SM, El-Adawy H, Farag HF, El-Taweel HA, Elhadad H, El-Badry AA-M. Detection and molecular identification of Blastocystis isolates from humans and cattle in northern Egypt. J Parasit Dis. 2021;45:738–745. doi: 10.1007/s12639-021-01354-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos BF, Brener B, de Figueiredo MA, Leles D, Mendes-de-Almeida F. Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in two domestic cats with chronic diarrhea. JFMS Open Rep. 2018;4:1–4. doi: 10.1177/2055116918774959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson C, Dridi S-M, Machouart M. Assessment of the role of Trichomonas tenax in the etiopathogenesis of human periodontitis: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng-rong Y, Zong-Da M, Xin W, Yu-Lan L, Yu-Xian Z, Qin-Po Z. Diarrhoea surveillance in children aged under 5 years in a rural area of Hebei Province, China. J Diarrhoeal Res. 1990;8:155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomicz L, Padzik M, Laudy AE, Kozłowska M, Pietruczuk A, Piekarczyk J, et al. Anti-Pentatrichomonas hominis activity of newly synthesized benzimidazole derivatives—in vitro studies. Acta Parasitol. 2009;54:165–171. doi: 10.2478/s11686-009-0024-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crucitti T, Jespers V, Mulenga C, Khondowe S, Vandepitte J, Buvé A. Trichomonas vaginalis is highly prevalent in adolescent girls, pregnant women, and commercial sex workers in Ndola, Zambia. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:223–227. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c21f93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos CS, De Jesus VLT, McIntosh D, Berto BP, Lopes CWG. Co-infection by Tritrichomonas foetus and Pentatrichomonas hominis in asymptomatic cats. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira. 2015;35:981–989. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos CS, McIntosh D, Berto BP, De Jesus V, Da Rocha C, Fernandes J, et al. Diagnosis of Pentatrichomonas hominis from domestic cats in Southeastern Brazil. Braz J Vet Med. 2015;37:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Girginkardeşler N, Coşkun Ş, Cü İ, Ertan P, Ok Z. Dientamoeba fragilis, a neglected cause of diarrhea, successfully treated with secnidazole. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;9:110–113. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00076-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegner R, Eskridge L. Effects of increasing the viscosity of culture media on the multiplication of Trichomonas hominis. J Parasitol. 1936;22:223–224. doi: 10.2307/3271849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W. The experimental infection of rats with Entamoeba histolytica; with a method for evaluating the anti-amoebic properties of new compounds. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1946;40:130–140. doi: 10.1080/00034983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongwutiwes S, Silachamroon U, Putaporntip C. Pentatrichomonas hominis in empyema thoracis. T Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:185–186. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaruddin M, Tokoro M, Rahman MM, Arayama S, Hidayati AP, Syafruddin D, et al. Molecular characterization of various trichomonad species isolated from humans and related mammals in Indonesia. Korean J Parasitol. 2014;52:471. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2014.52.5.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Li W, Gong P, Meng Y, Li W, Zhang C, et al. Molecular and morphologic identification of Pentatrichomonas hominis in swine. Vet Parasitol. 2014;202:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WC, Gong P-T, Ying M, Li J-H, Yang J, Li H, et al. Pentatrichomonas hominis: first isolation from the feces of a dog with diarrhea in China. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:1795–1801. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3825-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WC, Wang K, Zhang W, Wu J, Gu Y-F, Zhang X-C. Prevalence and molecular characterization of intestinal trichomonads in pet dogs in East China. Korean J Parasitol. 2016;54:703. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2016.54.6.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WC, Ying M, Gong P-T, Li J-H, Yang J, Li H, et al. Pentatrichomonas hominis: prevalence and molecular characterization in humans, dogs, and monkeys in Northern China. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:569–574. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4773-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WC, Wang K, Gu Y. Occurrence of Blastocystis sp. and Pentatrichomonas hominis in sheep and goats in China. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2671-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WC, Wang K, Li Y, Zhao L-P, Xiao Y, Gu Y-F. Survey and molecular characterization of trichomonads in pigs in Anhui Province, East China, 2014. Iran J Parasitol. 2018;13:602–610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahittikorn A, Udonsom R, Koompapong K, Chiabchalard R, Sutthikornchai C, Sreepian PM, et al. Molecular identification of Pentatrichomonas hominis in animals in central and western Thailand. BMC Vet Res. 2021;17:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12917-021-02904-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloni BP, Thompson RA, Hopkins RM, Reynoldson JA, Gracey M. The prevalence of Giardia and other intestinal parasites in children, dogs and cats from aboriginal communities in the Kimberley. Med J Aust. 1993;158:157–159. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb121692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloni D, Mantini C, Goustille J, Desoubeaux G, Maakaroun-Vermesse Z, Chandenier J, et al. Molecular identification of Pentatrichomonas hominis in two patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:933–935. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2011.089326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romatowski J. Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in four kittens. J AM Vet Med Assoc. 2000;216:1270–1272. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.216.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos CSd, Jesus VLTd, McIntosh D, Berto BP, Lopes CWG. Co-infection by Tritrichomonas foetus and Pentatrichomonas hominis in asymptomatic cats. Pesq Vet Bras. 2015;35:980–988. doi: 10.1590/S0100-736X2015001200007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stark D, Barratt J, Chan D, Ellis JT. Dientamoeba fragilis, the neglected trichomonad of the human bowel. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;29:553–580. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Zhang H, Yu Y, Gong P, Li J, Li Z, et al. High prevalence of Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3684-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]