Abstract

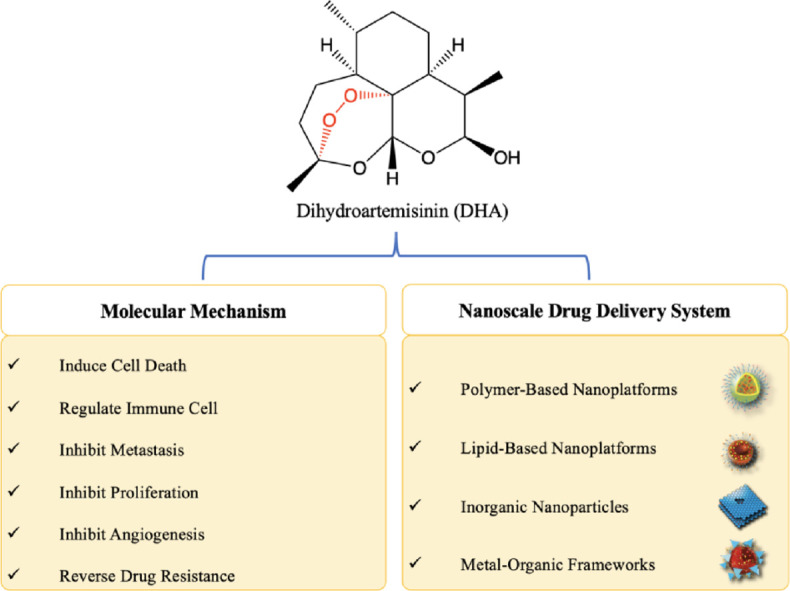

Dihydroartemisinin (DHA), a first-line antimalarial drug, has demonstrated great anticancer effects in many types of tumors, including liver cancer, glioblastoma, and pancreatic cancer. Due to its abilities to induce programmed cell death (PCD; apoptosis, autophagy and ferroptosis), inhibit tumor metastasis and angiogenesis, and modulate the tumor microenvironment, DHA could become an antineoplastic agent in the foreseeable future. However, the therapeutic efficacy of DHA is compromised owing to its inherent disadvantages, including poor stability, low aqueous solubility, and short plasma half-life. To overcome these drawbacks, nanoscale drug delivery systems (NDDSs), such as polymeric nanoparticles (NPs), liposomes, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), have been introduced to maximize the therapeutic efficacy of DHA in either single-drug or multidrug therapy. Based on the beneficial properties of NDDSs, including enhanced stability and solubility of the drug, prolonged circulation time and selective accumulation in tumors, the outcomes of DHA-loaded NDDSs for cancer therapy are significantly improved compared to those of free DHA. This review first summarizes the current understanding of the anticancer mechanisms of DHA and then provides an overview of DHA-including nanomedicines, aiming to provide inspiration for further application of DHA as an anticancer drug.

Keywords: Dihydroartemisinin, Ferroptosis, Nano-drug delivery, Chemodynamic therapy, Photodynamic therapy, Photothermal therapy

Graphical abstract

Anticancer mechanisms of DHA and overview of DHA-based nanoscale drug delivery systems

1. Introduction

Dihydroartemisinin (DHA), a derivative of the natural compound artemisinin and an active metabolite of artemisinin-derived compounds, which possesses higher bioavailability and stronger potency than artemisinin, is widely used to treat malaria due to its potent killing effect on plasmodia. Although its exact mechanism is still not fully understood, it is well accepted that DHA is activated when the endoperoxide bridge within its molecular structure is cleaved by ferrous iron (e.g., Fe2+, especially heme iron) to produce ROS and free radical intermediates [1]. Activated DHA, which exhibits high oxidative activities, can cause damage to membrane structure, chromosomes and proteins, stop nutrition supply and finally kill plasmodia. DHA also demonstrates potential anticancer activity via a similar mechanism in various types of tumors (e.g., liver cancer [2], leukemia [3], pancreatic cancer [4], colorectal cancer [5], glioblastoma [6]). Further studies proved that DHA exerts anticancer effects through multiple pathways; the related mechanisms include induction of apoptosis-, autophagy- and ferroptosis-mediated cell death [7], [8], [9], suppression of metastasis [10] and angiogenesis [11], and modulation of the tumor immune microenvironment [12]. DHA also shows a certain degree of selective cytotoxicity on cancer cells, which is partially attributed to the high sensitivity to ROS and high demand for iron elements maintained by high expression of transferrin (Tf) receptors in cancer cells [13,14]. In addition, the chemosensitivity to DHA can be enhanced in certain cancer cells, such as ovarian cancer cells with functional p53 gene status but not normal ovarian cell lines [15] or platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha (PDGFRα)-positive ovarian cancer cells (A2780 and OVCAR3) but not PDGFRα-null cells (SK-OV3, IOSE144 and OVCAR5 cells), through direct interaction with specific targets [16]. Therefore, these findings together with the claimed safety in clinic suggest that DHA is a promising candidate for cancer therapy [17].

The therapeutic efficacy of DHA is attenuated on account of its poor stability (mediated by breakage of the peroxide linkage) [18], low aqueous solubility [19], short plasma half-life (approximately 2 h) [20] and nonspecific distribution. Effective approaches are needed to address these issues. Nanoscale drug delivery systems (NDDSs) have recently gained much attention owing to their low biotoxicity, good biocompatibility and flexibility for functionalization [21]. Incorporation of DHA into NDDSs such as liposomes [22,23], micelles [24], graphene [25] and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [26] prolongs its blood circulation, increases its accumulation in tumors and significantly enhances its therapeutic effects. Additionally, integration of DHA with functionalized constituents such as Fe2+-enriched materials (e.g., Tf and Fe-containing MOF) and/or other therapeutic agents in NDDSs greatly promotes the tumor killing effect of the system. In this review, we comprehensively summarize the progress regarding the use of DHA in cancer research ranging from the investigation of its anticancer activities to the development of NDDSs for targeted therapy. We first report the findings from the systematic examination of the underlying anticancer mechanisms of DHA and then discuss the strategies to design DHA-based NDDSs. We conclude with a brief perspective on further anticancer research and applications of DHA, aiming to provide some inspiration for the clinical translation of DHA.

2. Molecular mechanisms of dihydroartemisinin for anticancer therapy

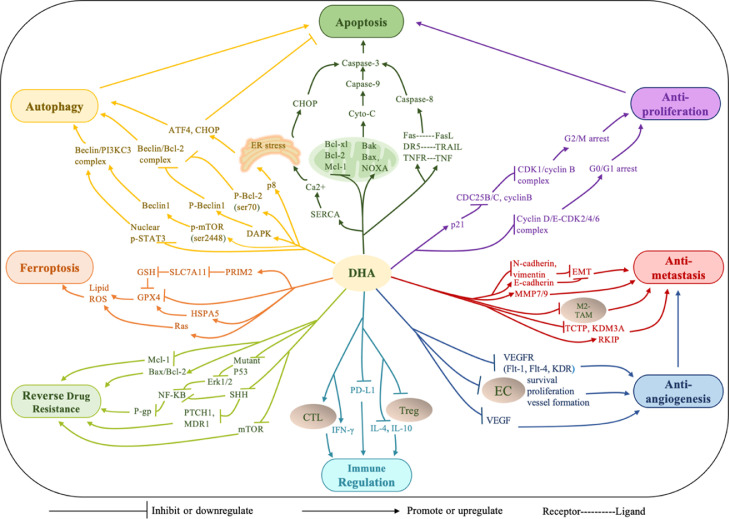

The anticancer potential of DHA has been evaluated in various types of cancers, and its underlying mechanisms have been explored in studies covering multistep processes of carcinogenesis, including survival, proliferation and metastasis. In this section, the current proven anticancer mechanisms of DHA are summarized (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Major anticancer mechanisms of dihydroartemisinin.

2.1. Direct induction of cell death

Cell death induction has been extensively studied because it is the main method for combating cancer. DHA-induced cell death is primarily a result of the attack of DHA on cellular components (e.g., DNA, proteins and lipids) and organelles (e.g., mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, lysosome), which induces ROS generation to cause oxidative damage and then activates the programmed cell death (PCD) process [27], [28], [29]. Collectively, DHA-induced PCD can be divided into three ways: apoptosis, ferroptosis and autophagy.

2.1.1. Apoptosis

Apoptosis, also known as type I PCD, is induced by DHA via the mitochondrion-dependent intrinsic pathway and death receptor-dependent extrinsic pathway. The intrinsic pathway is associated with the loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential, release of cytochrome C and activation of caspase-3/-9, which are promoted by DHA through the regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins, including the upregulation of proapoptotic proteins Bak [30], Bim [31], and NOXA [32] or the downregulation of antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 [33], Bcl-xl [15] and Mcl-1 [34]. The extrinsic pathway relies on the binding of death receptors (e.g., Fas, DR5, TNFR) with their corresponding ligands (e.g., FasL, TRAIL, TNF), which then activates caspase-8/-10, triggers the caspase-3 cascade and leads to apoptosis. The intrinsic and extrinsic pathways are always simultaneously triggered by DHA [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]. For example, DHA is reported to activate caspase-3/-8/-9, increase the levels of Bax and FAS and decrease the expression of Bcl-2 in human osteosarcoma cells, non-small-cell lung cancer and prostate cancer [37], [38], [39] .

2.1.2. Autophagy

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved degradative process that removes damaged organelles and supplies nutrients for cell survival under stressed conditions, including nutrient deprivation and cellular stress [40]. Autophagy can either promote tumor survival and drug resistance or contribute to autophagic cell death during tumorigenesis and tumor therapy, which partially depends on the levels of signaling molecules stimulated by therapeutic agents [41,42]. DHA is capable of inducing autophagy in various cancer cells, characterized by the formation of autophagosomes and autolysosomes, and results in the promotion of apoptosis [43], [44], [45], [46]. Moreover, autophagy increased when apoptosis was blocked, indicating the complex crosstalk between the two pathways. Mechanistically, DHA promotes autophagy by acting on the key regulator Beclin 1 (BECN1), which can interact with either Bcl‐2 or class III phosphatidyl inositol 3‐kinase (PI3KC3, also termed Vps34) to inhibit or induce autophagy [47]. DHA can decrease the formation of the Beclin 1/Bcl-2 complex and increase the formation of the Beclin 1/PI3KC3 complex in three ways. (1) DHA can upregulate proautophagic Beclin 1 expression by downregulating PI3K/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) phosphorylation at Ser2448, which increases the formation of the Beclin 1/PI3KC3 complex. Moreover, DHA enhances the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 at Ser70, inducing its dissociation from Beclin 1 and thus relieving the inhibition of autophagy and triggering autophagic cell death in HeLa cells [48]. (2) DHA induces phosphorylation at the BH3 domain of Beclin 1 by activating death‐associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1) [49]. This activation prevents the interaction of Beclin 1 with Bcl-2 and supports the interaction of Beclin 1 with PI3KC3 in human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. (3) DHA increases the expression of Beclin 1 by suppressing the nuclear translocation of the phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (p-STAT3), a transcription repressor of Beclin 1, resulting in autophagy-related death in human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells and inhibition of xenograft tumor growth [50].

2.1.3. Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis, unlike caspase-dependent apoptosis, refers to an iron-dependent form of PCD, which is driven by the accumulation of lipid ROS and the depletion of plasma membrane polyunsaturated fatty acids [51]. Various factors that are able to increase lipid ROS can contribute to ferroptosis; for example, the inhibition of system Xc− and/or glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) is highly essential in ferroptosis initiation [52]. On the one hand, DHA can work as an inhibitor of system Xc−, a heterodimeric cell surface amino acid antiporter that contains the transmembrane transporter protein SLC7A11 as the key functional module for transporting extracellular cystine to the cell, to promote the biosynthesis of glutathione (GSH) and thus preventing peroxidation [9,53]. Yuan et al. suggested that DHA downregulates SLC7A11 and then increases lipid ROS generation and mitochondrial malondialdehyde levels to cause ferroptosis in lung cancer cells [9]. On the other hand, DHA can work as an inhibitor of GPX4, which is a lipid repair enzyme responsible for reducing lipid ROS within biological membranes. Yi et al. demonstrated that DHA induced ferroptosis in glioblastoma cells by downregulating GPX4 to cause lipid ROS accumulation [54]. Similar results were observed in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. DHA downregulated both GPX4 and Ras (another protector of ferroptosis), increased cellular ROS production, altered mitochondrial morphology, caused atypical annexin V/PI staining and led to ferroptosis [55].

2.2. Inhibition of proliferation

Uncontrolled cell proliferation is a typical property of cancers that occurs as a result of the overexpression and aberrant activity of cell cycle proteins such as cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). Therefore, prevention of cell cycle progression (G1/G0-S-G2-M) through cycle arrest in cancer cells is an effective method for inhibiting tumor growth [56]. DHA treatment can induce cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 or G2/M phase by regulating cyclin-related pathways, thus stopping cell division and inhibiting tumor proliferation. For example, DHA induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in pancreatic cancer cells via downregulation of the cyclin E, CDK2, CDK4 and CDK6 proteins [57]. Likewise, DHA induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in gastric carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo by negatively regulating the cyclin D1-CDK4-Rb signaling pathway [58]. Similar results of an increased G0/G1 population after DHA treatment were also observed in breast cancer [59], colorectal cancer [60] and glioma [61]. The antiproliferative effect of DHA is also associated with G2/M phase cell cycle arrest accompanied by upregulation of p21 and downregulation of cyclinB, CDC25B and CDC25C [37,62,63]. In particular, DHA inhibits epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) cell growth by inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest without inducing apoptosis, which suggests the critical role of DHA in EOC cell cycle control [62]. In some cases, DHA synergistically inhibits cell proliferation when combined with other therapeutic agents. DHA coadministration with gefitinib downregulated the expression of G2/M regulatory proteins, including cyclin B1 and CDK1, in lung cancer cells, leading to cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase [64].

2.3. Inhibition of angiogenesis

The formation of new blood vessels is a crucial process in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Therefore, disrupting tumor angiogenesis has served as an important strategy for cancer treatment to achieve favorable therapeutic outcomes. DHA significantly downregulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in various cancer cells [65], [66], [67] and also downregulates proangiogenic VEGF receptors (VEGFR, typically Flt-1, Flt-4, KDR/flk-1) expression on lymphatic endothelial cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) by targeting different parts of the VEGF cascade, remarkably preventing vessel formation [68,69]. In addition, direct inhibition of endothelial cells (ECs) also strongly halts the progression of angiogenesis, as ECs are major components of vessels. Specifically, DHA inhibits the proliferation, induces the apoptosis or anoikis and promotes the autophagy of ECs by suppressing the extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway, activating the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway and downregulating the Akt/mTOR pathway, respectively [70], [71], [72]. Furthermore, DHA can also prevent ECs from forming a vascular plexus by inhibiting the phosphorylation of STAT3 and the subsequent expression of fatty acid synthase (FASN) [73].

2.4. Inhibition of metastasis

Metastasis is a typical feature of malignant tumors and, more importantly, is the main cause of cancer-related death [74]. DHA inhibits the invasion, migration, and metastasis of tumors in the following three ways. First, DHA can reverse epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by regulating related signaling molecules and/or reducing subsequent matrix degradation by downregulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). For example, Chen et al. reported that in esophageal cancer cells (TE-1 and Eca-109) [75], DHA reversed the EMT program, which corresponded to a decrease in EMT-associated markers N-cadherin and vimentin and an increase in E-cadherin, the key marker of the epithelial phenotype. In this case, metastasis was blocked because the tumor cells failed to acquire heightened invasiveness through EMT. For other examples, DHA reduced lung metastasis formation in a highly invasive HepG2 (CD133(+) Hep-2) tumor-bearing model by suppressing MMP9 expression, inhibiting STAT3 activation and upregulating E-cadherin [76]. DHA also attenuated cell migration and invasion by inhibiting MMP9 and MMP7 in glioma cells and gastric cancer cells [77,78]. Second, DHA can inhibit metastasis by upregulating metastasis suppressors or downregulating metastasis promoters as well as by regulating energy metabolism. It can serve as an inhibitor of translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP), a confirmed marker of a poor prognosis in gallbladder cancer (GBC), and thus disrupt the metastatic potential of GBC cells [79]. The antimetastatic effect of DHA is also exerted through its upregulation of Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP, a metastasis suppressor) in cervical cancer cells [80] and inhibition of lysine demethylase 3A (KDM3A, metastasis promoter) in bladder cancer cells [81]. Interestingly, DHA suppresses the migration and invasion of NSCLC cells (A549 and H1975 cells) by reduction in glucose metabolism and energy supply through negative regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [82]. Third, DHA can act on nonneoplastic cells to prevent cancer metastasis, as metastasis depends not only on tumor cells themselves but also on the support and regulation of other cells in the tumor immune microenvironment. According to Chen's work, DHA prevents the polarization of M2-like tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) through STAT3 signaling inactivation, thereby reducing the number of M2 TAMs and inhibiting invasion, migration, and angiogenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [83].

2.5. Reversion of drug resistance

The emergence of resistance to chemotherapy always leads to therapeutic failure (>90%), which is currently one of the key challenges in cancer therapy [84]. DHA potentiates the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents in low-sensitivity tumoral cells through various routes, including augmentation of apoptosis and inactivation of adaptive responses. (1) Proapoptosis-based mechanisms of DHA-mediated reversal of resistance have been widely reported. DHA elevates ROS production and aggravates DNA damage, which sensitizes human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells to arsenic trioxide (As2O3)-induced cytotoxicity and promotes apoptosis. Under these conditions, DHA does not enhance the cytotoxicity of As2O3 to corresponding normal cells [85]. Similarly, DHA can be used to overcome 5-fluorouracil resistance in colorectal cancer cells via ROS-mediated apoptotic cell death, which might be due to the modulation of the Bcl-2/Bax protein ratio [86]. In dexamethasone-resistant multiple myeloma (MM) cells, DHA can reverse the upregulation of Bcl-2 protein induced by dexamethasone, overcoming drug resistance and inhibiting MM progression significantly [87]. (2) DHA inhibits several prosurvival signaling pathways that are overactivated in resistant tumor cells, such as the NF-κB [88,89], mTOR [90] and Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathways [91], to reverse drug resistance. For instance, DHA inhibits P-gp expression by downregulating the mutant p53 (R248Q)-ERK1/2-NF-κB signaling pathway. Decreased level of P-gp fails to pump out therapeutic agents, helping to overcome multidrug resistance [89]. DHA can also enhance cisplatin-induced proliferation inhibition and promote apoptosis in nonsensitive ovarian carcinoma cells partially through inhibition of the overactivated mTOR signaling pathway [90]. In particular, treatment with DHA promotes the death of platinum-resistant esophageal squamous cells through SHH signaling inactivation by inhibiting different parts of the SHH pathway, including the nuclear translocation of Gli1, a key transcription factor, and the transcription of PTCH and MDR1, the key downstream effectors [91]. Apart from conventional chemotherapeutics, DHA displays potential in overcoming resistance to protein kinase inhibitors, including small molecules such as imatinib and monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab, by inhibiting specific gene or protein expression in cancer cells. Lee et al. demonstrated that DHA inhibited the Bcr/Abl fusion gene at the mRNA level, restoring the sensitivity of resistant chronic myeloid leukemia cells to imatinib [92]. Amico et al. revealed that DHA enhanced trastuzumab efficacy in HER2-positive breast cancer cells through inhibition of phospho-TCTP levels, thus inducing mitotic aberration and enhancing the effect of trastuzumab on microtubules, finally killing cancer cells [93,94].

2.6. Immune cell regulation

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are the most important immune cells responsible for directly killing tumor cells after activation by specific tumor antigens; while certain immune cells in the tumor immune microenvironment such as M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs, marked as CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) can inhibit the activation, maturation and function of CTLs, thus coordinating with tumor cells to promote tumor progression [95]. DHA can reprogram the immune cell-mediated immunosuppressive microenvironment into an immunosupportive microenvironment through the regulation of T cells, which is beneficial for the eradication of tumors. For instance, DHA increases the tumor infiltration and activity of CTLs by neutralizing IL-10-dependent Treg suppression in melanoma and by reducing the expression of IL-6 and increasing the expression of IFN-γ in the tumor and spleen [96]. Likewise, Noori et al. found that intratumoral injection of DHA significantly inhibited pancreatic tumor growth, which was related to a significant decrease in splenic Tregs and an increase in IL-4 levels [97]. Zhou et al. also found that DHA promoted the expansion and anticancer effect of gamma delta (γδ) T cells, another T cell group with antitumor effects. The underlying mechanism might be related to the upregulation of some cytotoxic function markers, such as perforin, granzyme B and IFN-γ [98]. Furthermore, DHA treatment inhibits PD-L1 expression, which contributes to immune escape by downregulating the PI3K/Akt, TGF-β, and STAT3 signaling pathways, overcoming radiation resistance and enhancing radiation sensitivity in integrated radiotherapy [99].

3. Nanoscale drug delivery of dihydroartemisinin

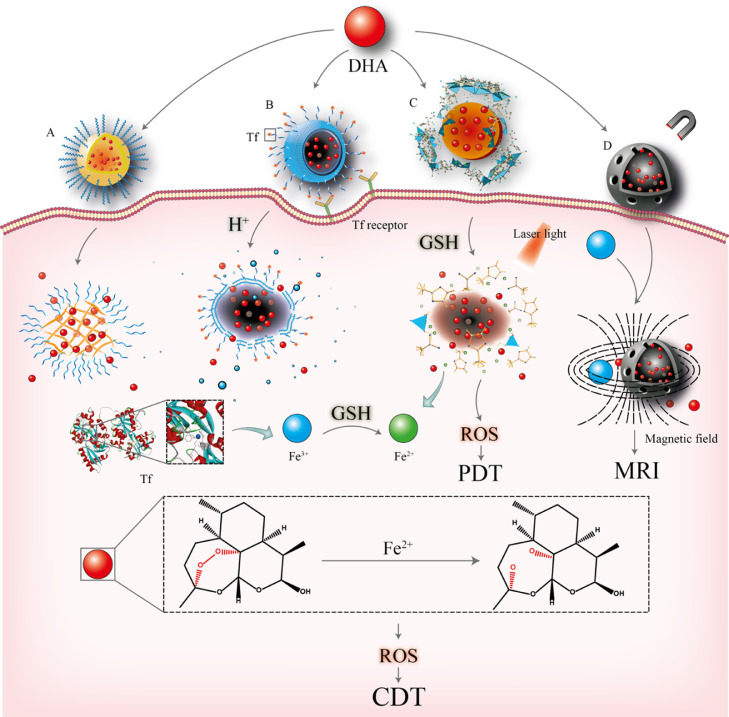

With the development of nanotechnology, NDDSs have emerged as promising tools for overcoming the drawbacks of small molecules and biomacromolecule drugs and enhancing their therapeutic efficacies. DHA-based NDDSs were thus designed and developed with improved solubility, prolonged circulation time, and importantly, increased anticancer activity. To optimize the functions of DHA-based NDDSs, cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) and targeting ligands can also be decorated onto the surface of carriers to enhance targeting ability. In addition, environment-response NDDSs can also be prepared by modifying the components of DHA-based NDDSs with the use of specific materials so that different stimuli, such as pH gradients, heat and magnetic fields can trigger the release of drugs from NDDSs. The various subtypes of DHA-based NDDSs are divided based on their composition and include polymer-based, lipid-based and inorganic-based nanoparticles (NPs) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Representatives of DHA-based NDDSs and their functions. (A) Polymer-based NPs; (B) Tf-modified lipid-based NPs; (C) MOFs (inorganic-based NPs) designed for photodynamic therapy; (D) Magnetic NPs with Fe3+ served as a magnetic resonance imaging agent. DHA is released from the NDDSs once the drug vehicles are delivered to the tumor sites. The endoperoxide bridge of DHA is cleaved by Fe2+ to produce ROS and free radical intermediates for cancer therapy.

3.1. Polymer-based nanoplatforms

Polymer-based NPs are usually composed of biodegradable polymers that are metabolized and removed from the body after hydrolysis. DHA-mediated polymeric NDDSs can be formed via chemical conjugation of drugs and polymers or physical encapsulation. Both polymeric nanoformulations have their own niche and show promise in cancer therapeutic applications.

3.1.1. DHA-conjugated polymeric nanoparticles

DHA-conjugated polymeric NPs are formed through the self-aggregation of amphiphilic DHA-polymer hybrid materials. The resulting systems with consistent chemical compositions and high drug loading capacity can improve the aqueous solubility of DHA, achieve targeted delivery and reduce toxicity, which ultimately enhance the curative efficacy. (1) The most basic structure of these systems consists only of DHA and polymers. For example, Robin et al. developed a DHA-hyaluronic acid (HA) conjugate in which the linkage was formed chemically through the esterification between the hydroxyl group of DHA and the carboxylic groups of HA [19]. As there are several carboxylic groups in HA, a relatively high drug loading content (12.33%) was achieved, which was beneficial for improving cytotoxicity in lung cancer cells. Additionally, the cellular uptake was enhanced as HA bound to the transmembrane glycoprotein CD44 overexpressing in cancer cells. In some cases, DHA-polymer hybrids are conjugated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and targeting ligands such as Tf, which are able to actively target the receptors overexpressed in tumor tissues [100]. A Tf-modified 8-arm PEG-DHA NP was prepared to target Tf receptors, which showed significantly high drug loading capacity (10.39%), improved solubility (over 100-fold), prolonged blood circulation, increased cellular uptake and improved therapeutic efficacy with low toxicity in lung cancer cells as compared to free DHA [101]. (2) Apart from the polymer hybrids containing only single drug (DHA), dual drug conjugates have also been developed for combination therapy. By conjugating paclitaxel (PTX) and DHA with PEG, the obtained NPs showed high entrapment efficacy (∼80.70% and 98.80% for DHA and PTX, respectively) and loading capacity (9.94% and 17.21% for DHA and PTX, respectively), which significantly enhanced the apoptosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma at a low dose of PTX (5 mg/kg) while combination of free drugs or mono-PTX therapy could not prevent tumor growth. The developed dual-drug system exhibited the ability to reduce the severe side effects when a high dose of free PTX was applied to cancer therapy, thus demonstrating the potential of DHA in combination cancer chemotherapy [102].

3.1.2. DHA-encapsulated polymeric nanoplatforms

In contrast to DHA-conjugated polymers with fixed drug-carrier composition, the drug-to-carrier ratio of DHA-encapsulated polymeric nanoplatforms can be easily adjusted to increase the encapsulation efficiency and to modify the drug release behaviors without involving multiple chemical reactions. In many cases, more than one type of polymer can be contained in a DHA-encapsulated system. For instance, DHA-phospholipid complex NPs coated with biodegradable poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) [103] or PEG methyl ether-poly(e-caprolactone) (MPEG-PCL) DHA polymeric micelles [104] were prepared to prevent drugs from rapid blood/renal clearance and suppress premature burst release. When compared with the unformulated drug, the polymeric NPs significantly enhanced the cytotoxicity of DHA. In some cases, more than one drug can be encapsulated into the system. Coloading DHA and other therapeutic agents into well-defined nanoplatforms can avoid resistance mechanisms and enhance synergistic efficacy. Doxorubicin (DOX) and DHA were coloaded into a micellar system with encapsulation efficiencies of both drugs over 90%, which exhibited synergistic therapeutic efficacy against breast cancer and also reduced systemic toxicity during the treatment when compared to a single drug or the free form of drugs [105]. For another example, Duan et al. designed a DHA and oxaliplatin (OxPt) coloaded nanoscale coordination polymer (NCP) for synergistic ROS generation with α-PD-L1 coadministration. The NPs were able to convert treated tumors into an in situ vaccine, which provided an effective approach to initiating immune-mediated eradication and generating long-term immunity. This NCP achieved 100% of tumor eradication after repeated dosing and the long-lasting antitumor immunity prevented the tumor reoccurrence when cured mice were treated with cancer cells. These satisfied results indicated the potential use of DHA in combination with immunotherapy [106].

3.2. Lipid-based nanoplatforms

Lipid-based nanoplatforms offer unique characteristics and advantages in the optimization of DHA delivery, such as controllable particle size and multifunctional applications. Various types of carriers, including solid NPs [107,108], liposomes [109], [110], [111] and biomimetic vesicles derived from the cell or cell membrane [112,113], have been developed in recent years. Among them, liposomes are the most widely used for DHA delivery.

Conventional liposomes improved the bioavailability and solubility of DHA. By adding PEG to the composition, stealth liposomes that avoided recognition and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system were obtained and greatly prolonged the blood circulation time of DHA [114,115]. However, the hydrophilic steric barrier of the PEG moiety might decrease the uptake of DHA into tumor cells, causing lower cytotoxicity than that of conventional liposomes [115]. In order to solve the issue, CPPs can be incorporated onto the surface of conventional liposomes to enhance the tumor homing and tumor growth inhibition ability of the system. Through surface modification with cationic arginine 8 (R8, sequence: RRRRRRRR), the CPP facilitated the binding of epirubicin-DHA coloaded liposomes with non-small-cell lung cancer cells [116]. This system addressed the drawback of anticancer drugs and effectively suppressed vasculogenic mimicry channels and cancer metastasis in A549 cells. In addition to CPPs, modifying liposomal surface with targeting molecules can also provide great convenience for specific biodistribution and promote cellular uptake of DHA because many receptors are overexpressed within cancerous tissues. For example, octreotide-modified liposomes enhanced the cytotoxicity and cellular uptake of DHA and daunorubicin by actively targeting somatostatin receptors, resulting in blockade of the migration of breast cancer cells [117]. Other ligand-modified lipid-based NPs of DHA with similar functions have also been reported. Wang et al. reported apolipoprotein B-100-modified lipid NPs of DHA that target low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLRs) in liver cancers [118]; Shen et al. selected n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, which has a better GLUT1 affinity than glucose, for targeted delivery of DHA to treat liver carcinoma [23]. In addition, Kang et al. utilized mannosylated liposomal DHA to target mannose receptors in colon cancer [119]. The cell internalization, tumor distribution and therapeutic outcomes of DHA were all improved in these cases. However, there are chances of happening off-target delivery if the single ligand-decorated liposomes do not show sufficient responsiveness or the receptors are saturated. To improve the situation, dual ligand-modified liposomes can be designed for preferential tumor accumulation in the future.

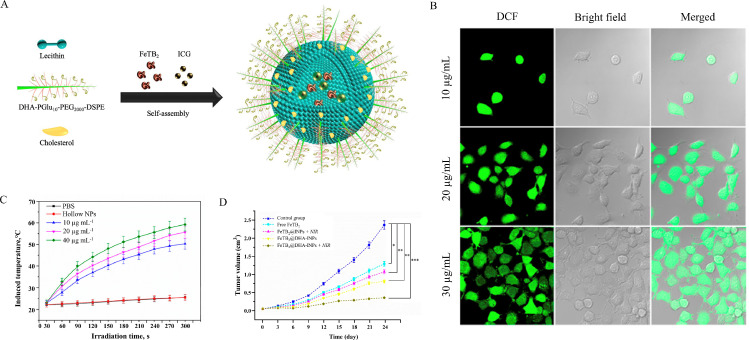

Apart from formulations with targeting ability, the use of environment-responsive multifunctional lipid-based NPs are common for DHA delivery. The functions of the system can be triggered in the presence of stimuli such as pH gradients, magnetic fields, light and heat. (1) pH-sensitive lipid-based NPs usually release payload when the conformation of lipid composition changes at acidic pH. For example, Yu et al. designed a Tf-surface-modified pH-sensitive liposome containing dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) for active targeted delivery of DHA [120]. The liposomes released approximately 80% of the drug contents at pH 5.0, while only 10% release was observed at pH 7.4. Under the acidic tumor microenvironment, the payloads were released and DHA was activated to produce abundant ROS for tumor inhibition. (2) Magnetically targeted lipid-based NP is another powerful tool to deliver DHA for achieving selective tumor accumulation. Magnetic active ingredients, especially iron oxide (Fe3O4), are often used for oriented drug transport based on the interaction between magnetic material and the magnetic field. Li et al. prepared DHA-loaded magnetic nanoliposomes (MLPs) with encapsulated Fe3O4 [22]. The presence of iron led to the directional movement of MLPs under magnetic field exposure and the targeted transportation strengthened the tumor suppression ability of DHA. (3) Light- and heat-sensitive liposomes have also been developed for DHA therapy, as demonstrated by You et al. (Fig. 3) [121]. A photosensitizer indocyanine green (ICG) was encapsulated in the liposomes, and the surface of the nanocarriers was modified with DHA-grafted polyglutamic acid. Once ICG was exposed to near infrared (NIR) irradiation, heat was generated to depolymerize the lipid-polymer shell, releasing therapeutic agents (FeTB2 and DHA). On the one hand, the released FeTB2 directly killed the tumor cells by inducing DNA arrest. On the other hand, Fe2+ catalyzed the DHA via Fenton reaction to increase ROS levels, which further led to oxidative damage. When compared with free drug, the antitumor activity of NDDSs was promoted and the toxicity was reduced in normal cells.

Fig. 3.

(A) Self-assembly of ICG and FeTB2-embedded DHA-grafted nanoparticles (FeTB2@DHA-INPs). (B) CLSM images of MCF-7 cells incubated with FeTB2@DHA-INPs for different concentrations (10, 20 and 30 µg/ml) to evaluate the capability of ROS generation. (C) The NIR induced temperature curves of the nanoparticle suspension with different concentrations (10, 20 and 40 µg/ml). (D) Relative tumor volume growth curves in different treatment groups of tumor-bearing mice (*P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001) (Adapted with permission from [121]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.).

3.3. Inorganic nanoparticles

Various inorganic NPs, including graphene [122,123], silica [124] and metallic NPs [125,126], have been explored for imaging and therapy in the field of oncology. Both their internal chemical stabilities and finely tunable manners allow nanocarriers as promising agents to deliver DHA into tumoral tissue and lead to a stronger tumor reduction than free DHA. A graphene-based system used for DHA therapy was reported [25]. Tf and DHA were coloaded by making use of the plentiful active groups such as carboxyl groups (-COOH) on the superb large surface area of graphene oxide (GO). In this system, Tf not only functioned as a tumor targeting ligand but also a ferric ion carrier to react with DHA, yielding ROS production for tumor killing. Besides carboxyl groups, hydroxyl groups (-OH) and epoxide groups are common to be present in GO, which make GO an ideal platform with high loading capacity for targeted combination cancer therapy. In contrast to GO, metal-doped inorganic NPs can be used as imaging contrast agents. For example, manganese-doped mesoporous silica NPs (such as folate-grafted PEG-MMSNs@DHA) were prepared by doping the manganese-oxygen bonds (-Mn-O-) into the skeleton of normal mesoporous silica nanoparticles (-Si-O-Si-) for image-guided and targeted cancer therapy [127]. The presence of Mn2+ served as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) agent to monitor ferroptosis induced by DHA. These advantages of iron/manganese inorganic NPs inspired researchers to develop multimetal-loaded nanovehicles with higher efficacy for peroxide self-supplying anticancer therapy and more efficacious DHA-based combination therapies [127]. A dual metal ions Fe- and Mn-doped layered double hydroxide (MnMgFe-LDH/DHA) was synthesized by a coprecipitation method to exhibit excellent performance in chemodynamic therapy (CDT) and photothermal therapy (PTT) [128]. In this system, a high DHA loading can be achieved due to the special structure of LDH and electrostatic interaction between DHA and LDH. Then, the tumor accumulation of LDH/DHA produced local heat under near-infrared laser irradiation. Moreover, the degraded and co-released of Fe3+ and Mn2+ in tumor microenvironment not only increased the ROS supply via Fenton-like reactions with DHA, but also improved the photothermal conversion efficiency (10.7%), leading to efficient cell death.

3.4. Metal-organic framework nanoplatforms

MOFs, composed of metal ions and organic linkers via coordination interactions, have recently received great attention in the field of medicine [129], [130], [131]. This is likely because of their tailorable chemistry, adjustable pore size and excellent functionality [132]. Different MOFs, such as zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs), Materials of Institut Lavoisier (MILs) and other metal-organic coordination complexes, have been studied in the context of DHA-loaded cancer therapeutics. So far, it has been shown that MOFs prevent the early robust DHA release and hold great potential for diagnostic and therapeutic systems.

3.4.1. Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks

ZIFs are a type of MOF with zeolitic architecture and represent a novel and promising class of porous materials. Among them, ZIF-8, formed by coordination between Zn2+ and 2-methylimidazole, exhibits exceptional chemical stability and thermal stability under physiological conditions but displays acidic pH-sensitive degradation [133,134]. Based on the mentioned distinctive merits, ZIFs have recently emerged as ideal DHA carriers for controllable drug release. Li et al. developed rhombic dodecahedral DHA@ZIF-8 NPs by loading DHA into the framework of ZIF-8 with a high drug encapsulation efficiency of 77.2% [26]. The metal-ligand bonds in the framework were dissociated in the acidic microenvironment to boost the release of DHA (75.7% of DHA was released under pH 5.5 condition) for cancer therapy. And in vivo tumor inhibition ratio of the DHA@ZIF-8 NPs was improved as compared to free DHA group (76.7% VS 49.2%). Biomimetic ZIFs have also been developed to endow the system with self-targeting and immune evasion abilities. When Fe-doped ZIF-8 NPs were coated with HepG2 cancer cell membranes, the NPs could target homologous tumors and avoid strong phagocytosis by white blood cells for DHA delivery [135]. Furthermore, ferrous ions and DHA were released from the framework under the acidic tumor environment to exert antitumor effect (suppressing about 90.8% of tumor growth) without inducing significant toxicity. Based on the current development, the application of biomimetic nanoplatforms for DHA delivery can be further explored by using artificial cascade enzymes associated with DHA to effectively enhance the effects of biocatalytic immunotherapy in future.

3.4.2. Iron-based metal-organic frameworks

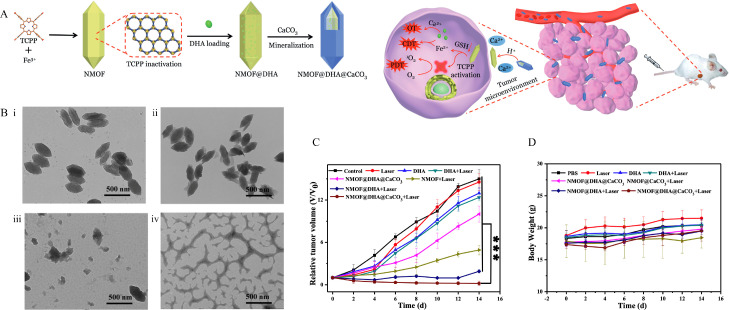

Iron-based MOFs, including MIL-100(Fe), MIL-101(Fe) and Fe-TCPP, show potential for DHA delivery. In addition to the general properties of MOFs, such as adjustable pore size and acidic-triggered drug release, a key and defining feature of iron-based MOFs is that these types of MOFs are iron self-supply systems, which can facilitate DHA-mediated ROS production via the Fenton reaction between DHA and Fe2+ to induce cancer death in the tumor microenvironment. Among them, the MIL-100/101(Fe) system is built by using trimers of metal octahedra and benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylate/benzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid, which functions as excellent vehicle for DHA storage/delivery via hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions. By introducing Fe3O4 NPs and carbon dots into the MIL-100 (Fe) system, magnetic-targeted delivery with fluorescence imaging for DHA therapy can be achieved [136]. In this system, DHA and Fe3+ were released upon reaching acidic tumor site. Then, the Fe3+ was reduced to Fe2+ and interacted with DHA for ROS production. Like other NDDSs, integration of all wanted therapeutic functions into one nanoplatform is desired. Another smart multifunctional MIL-101 (Fe)-based MOF loaded with DHA and a photosensitizer (methylene blue) was constructed for not only real-time imaging but also chemotherapy and photodynamic synergetic therapy to selectively kill the tumor. With the enzyme-responsive polylactic acid (PLA) coating, the resulting system showed pH/enzyme dual-responsive release for chemo-photodynamic synergetic therapy [137]. On the other hand, metal-containing components are introduced to iron-based MOFs, which yields novel physicochemical properties (Fig. 4). MOF with a CaCO3 mineralized coating prevents DHA leakage in the bloodstream. Specifically, the presence of CaCO3 enhances acidic pH-stimulated DHA release and improves the therapeutic efficiency of DHA by elevating the cytosolic Ca2+ level and Fe-TCPP-based phototoxicity [138]. Besides the mentioned systems, Fan et al. fabricated a MIL101-NH2 dual-dressed with photoacoustic and fluorescent signal donors and immune adjuvants for synergistic cancer photoimmunotherapy. Also, this system released payloads and Fe2+ in response to the tumor microenvironment. Although this system was not developed for DHA, it showed the potential to be a suitable nanocarrier to codeliver DHA with other therapeutic agents for combination cancer therapy [139].

Fig. 4.

(A) Schematic illustration of the preparation of the nanoplatform and the programmed drug release for cancer therapy. (B) TEM images of NMOF@DHA@CaCO3 in response to pH and GSH: i) pH 7.4, with GSH, ii) pH 6.5, without GSH, iii) pH 6.5, with GSH, treatment time is 30 min, iv) pH 6.5, with GSH, treatment time is 24 h. All scale bars are 500 nm. (C) Tumor growth curve after the mice receiving different treatments. (D) Body-weight changes within 14 d during treatment. (*P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001) (Reproduced with permission from [138]. Copyright 2019 Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.).

4. Challenges in clinical application

DHA exhibits antitumor effects against broad cancer types by inducing iron-dependent oxidative stress and activating multiple pathways that often work concurrently. However, it is remarkable that the prodeath mechanism of DHA is cell type-dependent and controversial, which may be due to the complex crosstalk in different processes. For example, DHA-induced autophagy promoted apoptosis in many cases, while in one case, DHA-induced autophagy led to resistance to DHA-induced apoptosis through upregulation of a stress-inducible protein p8 [140]. The rapid upregulation of p8 led to prosurvival autophagy through the p8-ATF4-CHOP axis, which attenuated apoptosis-mediated cell death under DHA treatment. As another example, DHA was observed to activate a negative feedback pathway that attenuates the anticancer effect. DHA treatment induced ferroptosis by upregulating heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 5 (HSPA5) levels in glioma cells through increased endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [141]. Subsequent upregulation of HSPA5 gave rise to GPX4 expression and activation, which neutralized lipid ROS and protected tumor cells from ferroptotic cell death. Therefore, the DHA-induced regulatory mechanisms remain elusive and are worth further exploration for clinical application in cancer therapy.

Another challenge is to develop suitable NDDSs to overcome the drawbacks of DHA (such as poor solubility, low bioavailability, and lack of specificity) for clinical application. In general, the use of ferrous materials shows great potential for DHA delivery for a few reasons. First, Fe3+ is reduced to Fe2+ ions in the presence of GSH, leading to controllable drug release. Second, the Fe2+ ions can catalyze ROS production from DHA. Third, the ferromagnetic property of iron endows the NDDSs with a response to the magnetic field, achieving targeted delivery. Finally, real-time images of drug delivery can be obtained by MRI due to the iron property of the system. However, the biosafety, pharmacokinetics and metabolism of these nanomedicines, especially metal component-contained inorganic NPs must be evaluated systematically, which is essential for clinical application. Up to now, some of the DHA formulations with good safety profiles have been developed and studied in animal models (Table 1), some of the data are promising, exhibiting the potential for clinical study.

Table 1.

Representative DHA-based NDDSs with in vivo data.

| DHA formulation | Cancer Type | Animal model | Dosage | Route | Safety issues | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tf-8arm-PEG-DHA NPs | Lewis lung carcinoma | LLC tumor-bearing female C57BL/6 mice | 5 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg DHA every 2 d | IV injection | Reduced hypersensitivity reactions; no severe hematotoxicity | [101] |

| DHA-PEG-PTX nanosystems | Colorectal cancer | HT-29 tumor-bearing Balb/c nude mice | 5 mg/kg PTX and 10 mg/kg DHA every 3 d | IV injection | No significant body weight loss | [102] |

| DHA/MPEG-PCL NPs | Cervical cancer | HeLa tumor-bearing female athymic BALB/C nude mice | 20 mg/kg DHA every 2 d | IV injection | No significant pathological changes, weight loss or inflammatory lesions | [104] |

| DOX and DHA coencapsulated Soluplus®-TPGS mixed micelles | Breast cancer | MCF-7 xenografted female BALB/c nude mice |

15 mg/kg DHA and/or 15 mg/kg DOX every 2 d | IV injection | Reduced the cardiotoxicity; avoided hepatic damage and necrosis | [105] |

| OxPt/DHA core-shell particles | Colorectal cancer | CT26 or MC38 tumor-bearing BALB/c, C57Bl/6 wild-type or Rag2−/− mice | 8 mg/kg OxPt, 2.86 mg/kg DHA, and/or 75 µg PD-L1 antibody every 3 d | IP injection | Reduced peripheral neuropathy | [106] |

| R8 modified epirubicin–DHA liposomes | Non-small-cell lung cancer | A549 tumor-bearing BALB/c nude mice | 3 mg/kg epirubicin; (epirubicin/DHA= 1:5, molar ratio) every 2 d | IV injection | Neglected systemic toxicity | [116] |

| LDLR-targeted lipid NPs coloading sorafenib and DHA | Hepatocellular carcinoma | HepG2 tumor-bearing BALB/c nu/nu nude mice | 5 mg/kg SRF and/or DHA every 3 d | IV injection | Reduced body weight loss as compared to free drugs | [118] |

| Alkyl glycoside-modified DHA liposomes | Hepatocellular carcinoma | H22 tumor-bearing specific-pathogen-free ICR mice | 70 mg/kg DHA everyday | IP injection | No significant body weight loss | [23] |

| Mannosylated liposomes coloading DOX and DHA | Colon cancer | HCT8/ADR xenografted female BALB/c nude mice | 1.5 mg/kg DOX and 60 mg/kg DHA every 2 d | IV injection | Avoided hepatic damage, multi-focal necrosis or apoptosis | [119] |

| Tf-decorated, DHA, L-buthionine-sulfoximine, and CellROX-loaded liposomes | Hepatocellular carcinoma | HepG2 tumor-bearing specific pathogen-free female BALB/c nude mice | 0.9 mg/kg DHA everyday | IV injection | No noticeable sign of organ damage | [120] |

| Magnetic DHA nano-liposomes | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Cal-27 xenografted male BALB/c mice | 10 mg/kg DHA everyday | IV injection | No significant body weight loss | [22] |

| FeTB2@DHA-INPs | Breast cancer | MCF-7 tumor-bearing male BALB/c mice | 1.64 mg/kg FeTB2 and 0.11 mg/kg DHA every 3 d | Intratumoral administration | No significant organ damage or inflammation lesion | [121] |

| DHA and Tf dual-dressed nano-GO | Breast cancer | EMT6 tumor-bearing female Balb/c mice | 0.2 mg/kg DHA every 2 d | IV injection | No significant pathological changes or weight loss | [25] |

| Folate-grafted PEG-MMSNs@DHA | Hepatocellular carcinoma | HepG2 tumor-bearing BALB/c nude mice | 10 mg/kg DHA every 2 d | IV injection | A large amount of nanocarriers were excreted through feces and urine 24 h after injection; no significant side effects | [127] |

| MnMgFe-layered double hydroxide loaded with DHA | Breast cancer | 4T1 tumor-bearing female Balb/c mice | 0.4 mg LDH and 0.2 mg DHA every 2 d | IV injection | No obvious side effects | [128] |

| DHA@ZIF-8 NPs | Hepatocellular carcinoma | H22 tumor-bearing Kunming mice | 5 mg/kg DHA every 2 d | IV injection | Negligible systemic toxicity | [26] |

| DHA-loaded Fe-doped ZIF-8 NPs coated with HepG2 cancer cell membranes | Hepatocellular carcinoma | HepG2 tumor-bearing male BALB/c nude mice | 100 µg DHA and 140 µg Fe/ZIF-8 every 3 d | IV injection | No distinct hepatic or renal toxicity; no obvious organ damage | [135] |

| DHA@Fe3O4@C@MIL-100(Fe) (DHA@FCM) | Cervical cancer | HeLa tumor-bearing female BALB/c nude mice | 223 µg DHA and 277 µg FCM every 3 d | IV injection | No appreciable pathological changes or inflammatory lesion | [136] |

| MOFs-MB-DHA@PLA@PEG | Cervical cancer | U14 tumor-bearing Kunming mice | 160 µg MOFs, 16 µg DHA and 0.32 µg of MB every 2 d | IV injection | No significant body weight loss | [137] |

| Fe-TCPP nanoscale MOF@DHA @CaCO3 | Breast cancer | 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice | 4 mg/kg MOF (dose of DHA is calculated based on the loading content of DHA in NMOF@DHA) | IV injection | No significant body weight loss, acute toxicity, organ damage or inflammatory lesions | [138] |

In the future, the combination of multiple therapeutic agents with DHA in a NDDS should be further explored. Currently, more evidence has shown that either DHA being a major anticancer agent or acting as an adjuvant drug in combination therapy is superior to monotherapy [102,106,121]. To maximize the therapeutic effects of DHA-based NDDSs, extensive experiments should be performed to investigate the best ratio of the loading therapeutic agents to exert synergistic effect. More importantly, it is of great significance to develop NDDSs with precise and controlled release manner because each payload has unique release profile, drug ratio may be altered during the release process. On the other hand, long-termed stability and storage of the NDDSs should also be considered as these factors highly affect the therapeutic efficacy of the formulations. Additionally, complicated NDDSs bring difficulties for quality control and scale-up production, which calls for more consideration in the preparation process and for production cost reduction.

5. Conclusion

In summary, although great strides have been made in the development of DHA-based cancer therapy, the repurposing of DHA into cancer drugs is still in its infancy. Current research on the formulation development of DHA for cancer treatment is mainly in the preclinical stage. Only one ongoing trial is registered on clinicaltrials.gov; the combined effect of icotinib and DHA in advanced NSCLC patients is assessed in this trial (NCT03402464). Thus, convincing data are needed to prove the efficacy of DHA for clinical cancer therapy. Meanwhile, developing all-in-one multifunctional nanoplatforms to load DHA with other therapeutic agents for photodynamic, chemodynamic or thermodynamic therapy as well as immunotherapy and real-time imaging are critical for future clinical translation. By utilizing the unique properties of each component, the therapeutic outcomes of the whole system can thus be maximized. As an FDA-approved antimalarial drug exhibiting potent anticancer potential, we believe that DHA has a bright future for further application in cancer treatment.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [51922111], the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macau SAR [File no. 0124/2019/A3], and Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Joint Laboratory of Optoelectronic and Magnetic Functional Materials [2019B121205002].

References

- 1.Wang J., Zhang C.J., Chia W.N., Loh C.C.Y., Li Z.J., Lee Y.M., et al. Haem-activated promiscuous targeting of artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10111. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao X.L., Luo Z.G., Xiang T.X., Wang K.J., Li J., Wang P.L. Dihydroartemisinin induces endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis in HepG2 human hepatoma cells. Tumori. 2011;97(6):771–780. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z., Hu W., Zhang J.L., Wu X.H., Zhou H.J. Dihydroartemisinin induces autophagy and inhibits the growth of iron-loaded human myeloid leukemia K562 cells via ROS toxicity. FEBS Open Bio. 2012;2:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H., Sun B., Pan S., Jiang H., Sun X. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits growth of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20(2):131–140. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283212ade. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu Z.H., Peng J.H., Zhang R.X., Wang F., Sun H.P., Fang Y.J., et al. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits colon cancer cell viability by inducing apoptosis through up-regulation of PPARγ expression. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2018;25(2):372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemke D., Pledl H.W., Zorn M., Jugold M., Green E., Blaes J., et al. Slowing down glioblastoma progression in mice by running or the anti-malarial drug dihydroartemisinin? Induction of oxidative stress in murine glioblastoma therapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7(35):56713–56725. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu Y.Y., Chen T.S., Qu J.L., Pan W.L., Sun L., Wei X.B. Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) induces caspase-3-dependent apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma ASTC-a-1 cells. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16(1) doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-16. :16-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia G., Kong R., Ma Z.B., Han B., Wang Y.W., Pan S.H., et al. The activation of c-Jun NH₂-terminal kinase is required for dihydroartemisinin-induced autophagy in pancreatic cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33(1) doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-33-8. :8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan B., Liao F., Shi Z.Z., Ren Y., Deng X.L., Yang T.T., et al. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits the proliferation, colony formation and induces ferroptosis of lung cancer cells by inhibiting PRIM2/SLC7A11 axis. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:10829–10840. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S248492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y., Gao S., Zhu J., Zheng Y., Zhang H., Sun H. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion in epithelial ovarian cancer via inhibition of the hedgehog signaling pathway. Cancer Med. 2018;7(11):5704–5715. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J.L., Wang Z., Hu W., Chen S.S., Lou X.E., Zhou H.J. DHA regulates angiogenesis and improves the efficiency of CDDP for the treatment of lung carcinoma. Microvasc Res. 2013;87:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S., Huang P., Gan J., Ling X., Du X., Liao Y., et al. Dihydroartemisinin represses esophageal cancer glycolysis by down-regulating pyruvate kinase M2. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;854:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Disbrow G.L., Baege A.C., Kierpiec K.A., Yuan H., Centeno J.A., Thibodeaux C.A., et al. Dihydroartemisinin is cytotoxic to papillomavirus-expressing epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2005;65(23):10854–10861. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerhardt T., Jones R., Park J., Lu R., Chan H.W., Fang Q., et al. Effects of antioxidants and pro-oxidants on cytotoxicity of dihydroartemisinin to Molt-4 human leukemia cells. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(4):1867–1871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiao Y., Ge C.M., Meng Q.H., Cao J.P., Tong J., Fan S.J. Dihydroartemisinin is an inhibitor of ovarian cancer cell growth. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28(7):1045–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X.G., Ba Q., Liu Y.L., Yue Q.X., Chen P.Z., Li J.Q., et al. Dihydroartemisinin selectively inhibits PDGFR alpha-positive ovarian cancer growth and metastasis through inducing degradation of PDGFR alpha protein. Cell Discov. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2017.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Z., Li Q., Wu J., Wang M.Y., Yu J.X. Artemisinin and its derivatives as a repurposing anticancer agent: what else do we need to do? Molecules. 2016;21(10) doi: 10.3390/molecules21101331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansen F.H. The pharmaceutical death-ride of dihydroartemisinin. Malaria J. 2010;9 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar R., Singh M., Meena J., Singhvi P., Thiyagarajan D., Saneja A., et al. Hyaluronic acid - dihydroartemisinin conjugate: synthesis, characterization and in vitro evaluation in lung cancer cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;133:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai T.M., Jian W.F., Guo Z., Xie Y.X., Dai R. Comparison of in vitro/in vivo blood distribution and pharmacokinetics of artemisinin, artemether and dihydroartemisinin in rats. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2019;162:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia R., Teng L., Gao L., Su T., Fu L., Qiu Z., et al. Advances in multiple stimuli-responsive drug-delivery systems for cancer therapy. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:1525–1551. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S293427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H., Li X., Shi X., Li Z., Sun Y. Effects of magnetic dihydroartemisinin nano-liposome in inhibiting the proliferation of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Phytomedicine. 2019;56:215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen S., Du M.B., Liu Q.B., Gao P., Wang J.G., Liu S.Z., et al. Development of GLUT1-targeting alkyl glucoside-modified dihydroartemisinin liposomes for cancer therapy. Nanoscale. 2020;12(42):21901–21912. doi: 10.1039/d0nr05138a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu W.F., Chen S.F., Wen Z.Y., Li Q., Chen J.H. In vitro evaluation of efficacy of dihydroartemisinin-loaded methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)/poly(l-lactic acid) amphiphilic block copolymeric micelles. J Appl Polym Sci. 2013;128(5):3084–3092. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu L., Wei Y., Zhai S., Chen Q., Xing D. Dihydroartemisinin and transferrin dual-dressed nano-graphene oxide for a pH-triggered chemotherapy. Biomaterials. 2015;62:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y., Song Y., Zhang W., Xu J., Hou J., Feng X., et al. MOF nanoparticles with encapsulated dihydroartemisinin as a controlled drug delivery system for enhanced cancer therapy and mechanism analysis. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(33):7382–7389. doi: 10.1039/d0tb01330g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang S., Chen H., Gerhard G.S. Heme synthesis increases artemisinin-induced radical formation and cytotoxicity that can be suppressed by superoxide scavengers. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;186(1):30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu M., Sun L., Zhou J., Yang J. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells through the mitochondria-dependent pathway. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(6):5307–5314. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1691-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen Y., Zhang B., Su Y., Badshah S.A., Wang X., Li X., et al. Iron promotes dihydroartemisinin cytotoxicity via ROS production and blockade of autophagic flux via lysosomal damage in osteosarcoma. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:444. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Handrick R., Ontikatze T., Bauer K.D., Freier F., Rübel A., Dürig J., et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis by a Bak-dependent intrinsic pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(9):2497–2510. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin G., Zhao C., Zhang L., Liu H., Quan Y., Chai L., et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis preferentially via a Bim-mediated intrinsic pathway in hepatocarcinoma cells. Apoptosis. 2015;20(8):1072–1086. doi: 10.1007/s10495-015-1132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cabello C.M., Lamore S.D., Bair W.B., 3rd, Qiao S., Azimian S., Lesson J.L., et al. The redox antimalarial dihydroartemisinin targets human metastatic melanoma cells but not primary melanocytes with induction of NOXA-dependent apoptosis. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30(4):1289–1301. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9676-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du W., Pang C., Xue Y., Zhang Q., Wei X. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits the Raf/ERK/MEK and PI3K/AKT pathways in glioma cells. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(5):3266–3270. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao N., Budhraja A., Cheng S., Liu E.H., Huang C., Chen J., et al. Interruption of the MEK/ERK signaling cascade promotes dihydroartemisinin-induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Apoptosis. 2011;16(5):511–523. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0580-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mi Y.J., Geng G.J., Zou Z.Z., Gao J., Luo X.Y., Liu Y., et al. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits glucose uptake and cooperates with glycolysis inhibitor to induce apoptosis in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu Y.Y., Chen T.S., Wang X.P., Li L. Single-cell analysis of dihydroartemisinin-induced apoptosis through reactive oxygen species-mediated caspase-8 activation and mitochondrial pathway in ASTC-a-1 cells using fluorescence imaging techniques. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(4) doi: 10.1117/1.3481141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji Y., Zhang Y.C., Pei L.B., Shi L.L., Yan J.L., Ma X.H. Anti-tumor effects of dihydroartemisinin on human osteosarcoma. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;351(1–2):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0716-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen T., Chen M., Chen J. Ionizing radiation potentiates dihydroartemisinin-induced apoptosis of A549 cells via a caspase-8-dependent pathway. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e59827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He Q., Shi J., Shen X.L., An J., Sun H., Wang L., et al. Dihydroartemisinin upregulates death receptor 5 expression and cooperates with TRAIL to induce apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9(10):819–824. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.10.11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21(22):2861–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mathew R., Karantza-Wadsworth V., White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nature Rev Cancer. 2007;7(12):961–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang H., Zou Z. Targeting autophagy to overcome drug resistance: further developments. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-01000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Q., Zhou X., Li C., Zhang X., Li C.L. Rapamycin promotes the anticancer action of dihydroartemisinin in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells by regulating expression of Atg7 and DAPK. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(4):5781–5786. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu W., Chen S.S., Zhang J.L., Lou X.E., Zhou H.J. Dihydroartemisinin induces autophagy by suppressing NF-κB activation. Cancer Lett. 2014;343(2):239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qu C., Ma J., Liu X., Xue Y., Zheng J., Liu L., et al. Dihydroartemisinin exerts anti-tumor activity by inducing mitochondrion and endoplasmic reticulum apoptosis and autophagic cell death in human glioblastoma cells. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:310. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu X., Liu Y., Zhang E., Chen J., Huang X., Yan H., et al. Dihydroartemisinin modulates apoptosis and autophagy in multiple myeloma through the P38/MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/6096391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mei Y., Glover K., Su M., Sinha S.C. Conformational flexibility of BECN1: essential to its key role in autophagy and beyond. Protein Sci. 2016;25(10):1767–1785. doi: 10.1002/pro.2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L., Li J., Shi X., Li S., Tang P.M., Li Z., et al. Antimalarial dihydroartemisinin triggers autophagy within HeLa cells of human cervical cancer through Bcl-2 phosphorylation at Ser70. Phytomedicine. 2019;52:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.09.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thongchot S., Vidoni C., Ferraresi A., Loilome W., Yongvanit P., Namwat N., et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis and autophagy-dependent cell death in cholangiocarcinoma through a DAPK1-BECLIN1 pathway. Mol Carcinog. 2018;57(12):1735–1750. doi: 10.1002/mc.22893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi X., Wang L., Li X., Bai J., Li J., Li S., et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces autophagy-dependent death in human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells through DNA double-strand break-mediated oxidative stress. Oncotarget. 2017;8(28):45981–45993. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang W.S., Stockwell B.R. Ferroptosis: death by lipid peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(3):165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao J.Y., Dixon S.J. Mechanisms of ferroptosis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sci. 2016;73(11):2195–2209. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu T., Ding W., Ji X., Ao X., Liu Y., Yu W., et al. Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis and its role in cancer therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(8):4900–4912. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yi R., Wang H., Deng C., Wang X., Yao L., Niu W., et al. Dihydroartemisinin initiates ferroptosis in glioblastoma through GPX4 inhibition. Biosci Rep. 2020;40(6) doi: 10.1042/BSR20193314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin R., Zhang Z., Chen L., Zhou Y., Zou P., Feng C., et al. Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) induces ferroptosis and causes cell cycle arrest in head and neck carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2016;381(1):165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Otto T., Sicinski P. Cell cycle proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Nature Rev Cancer. 2017;17(2):93–115. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen H., Sun B., Wang S., Pan S., Gao Y., Bai X., et al. Growth inhibitory effects of dihydroartemisinin on pancreatic cancer cells: involvement of cell cycle arrest and inactivation of nuclear factor-kappaB. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136(6):897–903. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0731-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fan H.N., Zhu M.Y., Peng S.Q., Zhu J.S., Zhang J., Qu G.Q. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits the growth and invasion of gastric cancer cells by regulating cyclin D1-CDK4-Rb signaling. Pathol Res Pract. 2020;216(2) doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mao H., Gu H., Qu X., Sun J., Song B., Gao W., et al. Involvement of the mitochondrial pathway and Bim/Bcl-2 balance in dihydroartemisinin-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer in vitro. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31(1):213–218. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu M., Sun L., Zhou J., Zhao Y., Deng X. Dihydroartemisinin-induced apoptosis is associated with inhibition of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase activity in colorectal cancer. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;73(1):137–145. doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu C.H., Liu Y., Xiao L.M., Guo C.G., Zheng S.Y., Zeng E.M., et al. Dihydroartemisinin treatment exhibits antitumor effects in glioma cells through induction of apoptosis. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16(6):9528–9532. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li B., Bu S., Sun J., Guo Y., Lai D. Artemisinin derivatives inhibit epithelial ovarian cancer cells via autophagy-mediated cell cycle arrest. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2018;50(12):1227–1235. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmy125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang C.Z., Zhang H., Yun J., Chen G.G., Lai P.B. Dihydroartemisinin exhibits antitumor activity toward hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83(9):1278–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jin H., Jiang A.Y., Wang H., Cao Y., Wu Y., Jiang X.F. Dihydroartemisinin and gefitinib synergistically inhibit NSCLC cell growth and promote apoptosis via the Akt/mTOR/STAT3 pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16(3):3475–3481. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aung W., Sogawa C., Furukawa T., Saga T. Anticancer effect of dihydroartemisinin (DHA) in a pancreatic tumor model evaluated by conventional methods and optical imaging. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(5):1549–1558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu X.H., Zhou H.J., Lee J. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits angiogenesis induced by multiple myeloma RPMI8226 cells under hypoxic conditions via downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and suppression of vascular endothelial growth factor secretion. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17(7):839–848. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000224443.85834.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee J., Zhou H.J., Wu X.H. Dihydroartemisinin downregulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression and induces apoptosis in chronic myeloid leukemia K562 cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57(2):213–220. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen H.H., Zhou H.J., Wang W.Q., Wu G.D. Antimalarial dihydroartemisinin also inhibits angiogenesis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53(5):423–432. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0751-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang J., Guo Y., Zhang B.C., Chen Z.T., Gao J.F. Induction of apoptosis and inhibition of cell migration and tube-like formation by dihydroartemisinin in murine lymphatic endothelial cells. Pharmacology. 2007;80(4):207–218. doi: 10.1159/000104418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dong F., Tian H., Yan S., Li L., Dong X., Wang F., et al. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits endothelial cell proliferation through the suppression of the ERK signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35(5):1381–1387. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu J., Ren Y., Hou Y., Zhang C., Wang B., Li X., et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces endothelial cell autophagy through suppression of the Akt/mTOR pathway. J Cancer. 2019;10(24):6057–6064. doi: 10.7150/jca.33704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang J., Guo L., Zhou X., Dong F., Li L., Cheng Z., et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces endothelial cell anoikis through the activation of the JNK signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2016;12(3):1896–1900. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gao P., Wang L.L., Liu J., Dong F., Song W., Liao L., et al. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits endothelial cell tube formation by suppression of the STAT3 signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2020;242 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.117221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liang W., Ferrara N. The complex role of neutrophils in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(2):83–91. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li N., Zhang S.Y., Luo Q., Yuan F., Feng R., Chen X.Q., et al. The effect of dihydroartemisinin on the malignancy and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of gastric cancer cells. Curr Pharm Biotechno. 2019;20(9):719–726. doi: 10.2174/1389201020666190611124644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang W.Y., Sun Y.J., Li X.M., Shi X.L., Li Z., Lu X.Y. Dihydroartemisinin prevents distant metastasis of laryngeal carcinoma by inactivating STAT3 in cancer stem cells. Med Sci Monitor. 2020;26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.922348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Que Z.Y., Wang P., Hu Y., Xue Y.X., Liu X.B., Qu C.B., et al. Dihydroartemisin inhibits glioma invasiveness via a ROS to P53 to beta-catenin signaling. Pharmacol Res. 2017;119:72–88. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liang R., Chen W., Chen X.Y., Fan H.N., Zhang J., Zhu J.S. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits the tumorigenesis and invasion of gastric cancer by regulating STAT1/KDR/MMP9 and P53/BCL2L1/CASP3/7 pathways. Pathol Res Pract. 2020;218 doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2020.153318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang F., Ma Q., Xu Z.H., Liang H.B., Li H.F., Ye Y.Y., et al. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits TCTP-dependent metastasis in gallbladder cancer. J Exp Clin Canc Res. 2017;36 doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0531-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hu C.J., Zhou L., Cai Y. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis of cervical cancer cells via upregulation of RKIP and downregulation of Bcl-2. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15(3):279–288. doi: 10.4161/cbt.27223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang T., Luo R., Li W., Yan H., Xie S., Xiao W., et al. Dihydroartemisinin suppresses bladder cancer cell invasion and migration by regulating KDM3A and p21. J Cancer. 2020;11(5):1115–1124. doi: 10.7150/jca.36174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jiang J., Geng G.J., Yu X.Y., Liu H.M., Gao J., An H.X., et al. Repurposing the anti-malarial drug dihydroartemisinin suppresses metastasis of non-small-cell lung cancer via inhibiting NF-kappa B/GLUT1 axis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(52):87271–87283. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen R., Lu X.Y., Li Z., Sun Y., He Z.X., Li X.M. Dihydroartemisinin prevents progression and metastasis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting polarization of macrophages in tumor microenvironment. Oncotargets Ther. 2020;13:3375–3387. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S249046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Longley D.B., Johnston P.G. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance. J Pathol. 2005;205(2):275–292. doi: 10.1002/path.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen H., Gu S., Dai H., Li X., Zhang Z. Dihydroartemisinin sensitizes human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells to arsenic trioxide via apoptosis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017;179(2):203–212. doi: 10.1007/s12011-017-0975-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yao Z., Bhandari A., Wang Y., Pan Y., Yang F., Chen R., et al. Dihydroartemisinin potentiates antitumor activity of 5-fluorouracil against a resistant colorectal cancer cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;501(3):636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen Y., Li R., Zhu Y., Zhong S., Qian J., Yang D., et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces growth arrest and overcomes dexamethasone resistance in multiple myeloma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:767. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang S.J., Gao Y., Chen H., Kong R., Jiang H.C., Pan S.H., et al. Dihydroartemisinin inactivates NF-kappaB and potentiates the anti-tumor effect of gemcitabine on pancreatic cancer both in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2010;293(1):99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang Y., He J., Chen J., Lin L., Liu Y., Zhou C., et al. Dihydroartemisinin sensitizes mutant p53 (R248Q)-expressing hepatocellular carcinoma cells to doxorubicin by inhibiting P-gp expression. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/8207056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Feng X., Li L., Jiang H., Jiang K., Jin Y., Zheng J. Dihydroartemisinin potentiates the anticancer effect of cisplatin via mTOR inhibition in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells: involvement of apoptosis and autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;444(3):376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cui W., Fang T., Duan Z., Xiang D., Wang Y., Zhang M., et al. Dihydroartemisinin sensitizes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma to cisplatin by inhibiting sonic hedgehog signaling. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.596788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee J., Shen P., Zhang G., Wu X., Zhang X. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits the Bcr/Abl oncogene at the mRNA level in chronic myeloid leukemia sensitive or resistant to imatinib. Biomed Pharmacother. 2013;67(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lucibello M., Adanti S., Antelmi E., Dezi D., Ciafrè S., Carcangiu M.L., et al. Phospho-TCTP as a therapeutic target of Dihydroartemisinin for aggressive breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(7):5275–5291. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.D'Amico S., Krasnowska E.K., Manni I., Toietta G., Baldari S., Piaggio G., et al. DHA affects microtubule dynamics through reduction of phospho-TCTP levels and enhances the antiproliferative effect of T-DM1 in trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines. Cells. 2020;9(5) doi: 10.3390/cells9051260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kitamura T., Qian B.Z., Pollard J.W. Immune cell promotion of metastasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(2):73–86. doi: 10.1038/nri3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yu R., Jin L., Li F., Fujimoto M., Wei Q., Lin Z., et al. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits melanoma by regulating CTL/Treg anti-tumor immunity and STAT3-mediated apoptosis via IL-10 dependent manner. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;99(3):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Noori S., Hassan Z.M. Dihydroartemisinin shift the immune response towards Th1, inhibit the tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. Cell Immunol. 2011;271(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhou Z.H., Chen F.X., Xu W.R., Qian H., Sun L.Q., Lu X.T., et al. Enhancement effect of dihydroartemisinin on human gammadelta T cell proliferation and killing pancreatic cancer cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17(3):850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang H., Zhou F., Wang Y., Xie H., Luo S., Meng L., et al. Eliminating radiation resistance of non-small cell lung cancer by dihydroartemisinin through abrogating immunity escaping and promoting radiation sensitivity by inhibiting PD-L1 expression. Front Oncol. 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.595466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Trowbridge I.S., Omary M.B. Human cell-surface glycoprotein related to cell-proliferation is the receptor for transferrin. P Natl Acad Sci-Biol. 1981;78(5):3039–3043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu K., Dai L., Li C., Liu J., Wang L., Lei J. Self-assembled targeted nanoparticles based on transferrin-modified eight-arm-polyethylene glycol-dihydroartemisinin conjugate. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29461. doi: 10.1038/srep29461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Phung C.D., Le T.G., Nguyen V.H., Vu T.T., Nguyen H.Q., Kim J.O., et al. PEGylated-paclitaxel and dihydroartemisinin nanoparticles for simultaneously delivering paclitaxel and dihydroartemisinin to colorectal cancer. Pharm Res. 2020;37(7):129. doi: 10.1007/s11095-020-02819-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]