Abstract

Background

Panax ginseng (ginseng) is a traditional medicine that is reported to have cardioprotective effects; ginsenosides are the major bioactive compounds in the ginseng root.

Methods

Magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer (MMIP) nanoparticles might be useful for both the extraction of the targeted (imprinted) molecules, and for the delivery of those molecules to cells. In this work, plant growth regulators were used to enhance the adventitious rooting of ginseng root callus; imprinted polymeric particles were synthesized for the extraction of ginsenoside Rb1 from root extracts, and then employed for subsequent particle-mediated delivery to cardiomyocytes to mitigate hypoxia/reoxygenation injury.

Results

These synthesized composite nanoparticles were first characterized by their specific surface area, adsorption capacity, and magnetization, and then used for the extraction of ginsenoside Rb1 from a crude extract of ginseng roots. The ginsenoside-loaded MMIPs were then shown to have protective effects on mitochondrial membrane potential and cellular viability for H9c2 cells treated with CoCl2 to mimic hypoxia injury. The protective effect of the ginsenosides was assessed by staining with JC-1 dye to monitor the mitochondrial membrane potential.

Conclusion

MMIPs can play a dual role in both the extraction and cellular delivery of therapeutic ginsenosides.

Keywords: Ginseng root, Ginsenoside Rb1, Molecular imprinting, Extraction, Myocyte

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury is the major pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1]. The Global Burden of Disease project predicts that CVD is likely to remain the leading cause of death for the foreseeable future [2]. Oxidative stress injury and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis plays a key role during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury [3]. Identification of natural antioxidants such as herbs is one important strategy to develop safe and effective anti-myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury drugs [4]. Ginsenosides are natural product steroid glycosides and triterpene saponins, and found almost exclusively in the plant genus Panax (ginseng) [5]. They have been shown to have numerous and varied therapeutic uses [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. Of special relevance to this work, ginsenoside Rb1 exerts antioxidant functions and thus has protective effects on human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro [13], and can prevent the ischemic brain damage or ischemic injury to spiral ganglion cells by scavenging free radicals [[14], [15], [16], [17]]. Ginsenoside Rb1 was found to provide myocardial protection by inducing an estrogen receptor-dependent crosstalk among the Akt, JNK, and ERK 1/2 pathways to prevent injury to H9c2 cardiomyocytes and apoptosis induced by hypoxia-reoxygenation [18]. Moreover, this protects the mitochondria by reducing the release of cytochrome c and the expression of cleaved-caspase-3 in the cytoplasm, ultimately reducing apoptosis [19].

Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) have been developed for detection, separation, purification, and delivery of bioactive molecules [20,21]. Encapsulation of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) into MIPs is often used to facilitate separation by magnetic fields [20,22,23]. The use of molecular fragments as templates or epitopes for the recognition of larger molecules is of great current interest [20], but when the whole molecule is relatively inexpensive, it is preferable to that as the template, and this is the approach we take here [21].

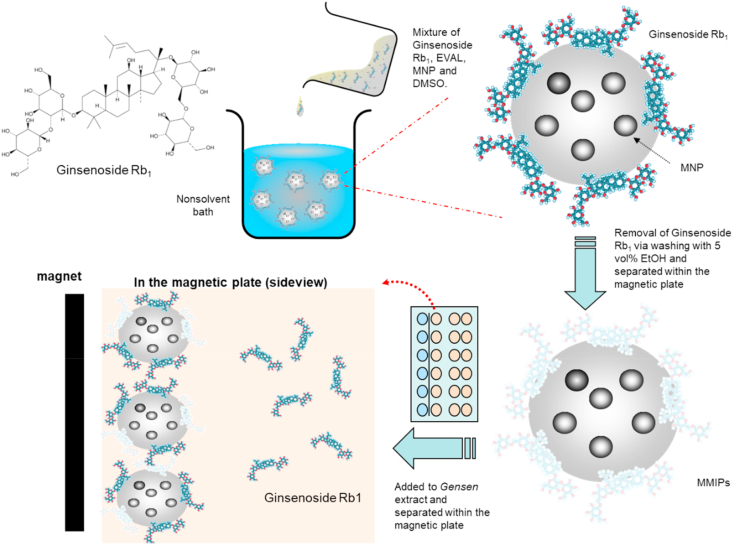

In this work, ginseng root growth from explants was induced, and the roots were then extracted with ethanol. Magnetic molecularly imprinted polymers (MMIPs) were prepared with magnetic nanoparticles, poly (ethylene-co-vinyl alcohol)s, EVALs, and templates via phase separation of a polymer solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) on introduction into a non-solvent. The synthesized MMIPs were then characterized by dynamic light scattering to determine size distribution, and by atomic force microscopy to examine surface morphology. The binding capacity and the extraction of ginsenosides with MMIPs was then measured by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The viability of H9c2 cardiomyocytes, after treatment with CoCl2 to induce hypoxia, was measured after incubation with ginseng root extract or ginsenoside-loaded MMIPs. Finally, the mitochondrial membrane potential in hypoxic myocytes was monitored by the staining of JC-1 aggregates or monomers.

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents and chemicals

Ginsenosides obtained from ChromaDex Inc (CA, USA). Poly(ethylene-co-vinyl alcohol) (EVAL), iron (III) chloride 6-hydrate (97%), 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) and JC-1 mitochondria staining kit For mitochondrial potential changes detection were from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). 1-Phenyl-3-(1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)-urea (TDZ) was from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osako, Japan). Iron (II) sulphate 7-hydrate (99.0%), hydrochloric acid and sodium hypochlorite were from Panreac (Barcelona, Spain). Acetonitrile and methanol high purity (>99.9%) for HPLC grade were from Fisher Scientific (NJ, U.S.A.) and Aencore Chemical PTY., LTD. (Surrey Hills, Australia), respectively. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, purity>99.9%) was ordered from J. T. Baker Chemical Co., (Phillipsburg, NJ). Lanosterol was obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., LTD (Japan). Gibco Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium and nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12) were purchased from Life Technologies Corporation by Gibco company. Cobalt (II) chloride hexahydrate, (purity 98%) was from Alfa Aesar by Thermo Fisher Scientific. All chemicals were used as received unless otherwise mentioned.

2.2. Induction of adventitious roots from ginseng callus

Six-month-old ginseng calluses (each approximately 0.1 g) were tested for the ability to form adventitious roots in the presence of plant growth retardants (PGRs), including 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), combinations of NAA and TDZ. All the calluses were cultured in an incubator with a 16/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod at an irradiance of 42–55 μmol m−2 s−1 and a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C. Twenty replicates were prepared for each PGR combination. The percentage of rooting, number of roots and length of the longest root were scored for four rooting calluses in each treatment, after three months of culture.

2.3. Extraction of ginsenosides from the extract of ginseng roots

The formation (see Scheme 1) and characterization of magnetic ginsenoside Rb1-imprinted EVAL nanoparticles can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) S1.1 and S1.2. respectively. Adventitious roots of ginseng from callus were dried in a 50 °C oven for 24 h. The dried roots were soaked in 95% ethanol for one week at room temperature, at weight ratio 1:50. Then the root and ethanol mixture were sonicated using a 200 W ultrasonic cleaning tank for 3 h. The mixture was then heated to 80 °C using an efflux condensing tube for 1 h, Next, the ethanol was removed using rotary evaporation (IKA RV10, Germany) at 1000 mbar (0.987 atm) and 20 rpm for 1 h. The concentrated ginsenoside was collected after centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 5 min, and examined by HPLC. This ginsenoside stock solution (250 μL) was then exacted with 100 μg of MMIPs (Rb1 as template) particles in an eppendorf for 30 min without mixing, and then particles were collected using a magnetic plate. Next, 5 vol% of ethanol 250 μL was added into the collected MMIPs for the elution of ginsenosides from MMIPs using the automatic working mode of a vortex mixer for 10 min and then the extraction solution was obtained using a magnetic plate. The adsorption of Rg1 and Rb1 from the extract of ginseng roots with MMIPs, stock and remaining were analyzed by HPLC as described in the Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) S1.3.

Scheme 1.

The preparation of magnetic ginsenoside Rb1-imprinted EVAL nanoparticles (MMIPs) and their use for the extraction of ginsenoside Rb1 from ginseng root extract.

2.4. Cell culture and hypoxia/reoxygenation treatment

The H9c2 cardiomyocyte cell line from rat heart myoblast was purchased from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center (BCRC; Taipei, Taiwan). The control groups of H9c2 cells were cultured in DMEM medium of high glucose with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere without CoCl2. The hypoxia-reoxygenation of H9c2 cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium without glucose at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere using 30 μg/mL CoCl2 for 24 h. For all experiments, H9c2 cells of 1 × 104 per well were seeded in 24-well plates for 24 h.

2.5. Cell viability and JC-1 staining

The H9c2 cells (1 × 104 cells) were seeded in 24-well plates and treated with/without 4 μM CoCl2 in DMEM/F12 medium at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h on the 1st day. Cobalt chloride (CoCl2) induces chemical hypoxia of H9c2 cardiomyocytes [24,25]. The Cell Counting Kit-8(CCK-8) (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to measure cytotoxicity of CoCl2 with and without MNIPs/ginsenosides-loaded MMIPs. Medium was removed from each well, and then 50 μL CCK-8 and 450 μL DMEM was added in each well on the 2nd day (1 day after seeding.) The 24-well plate was incubated for a further 3 h at 37 °C before ELISA measurements. The absorption intensities were measured at 450 nm (I450) and the reference absorption (Iref) at 650 nm by an ELISA reader (CLARIOstar, BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). The cellular viability (%) was then calculated from the ratio of effective absorption (I450–Iref) of experimental cells to controls. The CCK-8 solutions were removed. The ginsenosides were exacted from the concentrated ginsenoside solution (250 μL) using 100 μg MMIP as described in section 2.3. The bound ginsenosides on MMIPs were washed off and measured using HPLC (the amount of bound ginsenoside Rb1 was 51.5 mg/g MMIPs).

The ginsenoside-loaded MMIPs were collected using a magnetic plate, and then added to DMEM medium to obtain a final concentration of 100 μM of (MMIP-bound) ginsenoside Rb1. Then 500 μL of the ginsenoside-loaded MMIPs/DMEM solution was added to each well on 24 well plate, and then incubated 24 h. The ginsenoside-loaded MMIPs/DMEM solution was replaced every day with fresh MMIP/ginsenoside solution. The cellular viability (%) was obtained using CCK-8 test on the 2nd and 5th day. For JC-1 staining, culture medium was removed and cells were washed with 0.5 mL PBS for each well. The 400 μL JC-1 solution was added and cells were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C. The JC-1 agent was removed and the cells were washed twice with DMEM medium. The stained cells were observed by fluorescence microscopy and analyzed on a fluorescent microplate reader (CLARIOstar, BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). The fluorimeter excitation is 525 nm and 490 nm for JC-1 aggregates and monomer, respectively. The fluorimeter emission wavelengths are 590 nm and 530 nm.

3. Results and discussion

Several treatments of plant growth regulators (PGRs) were found to induce adventitious rooting from callus of P. ginseng, Table 1. PGR 2,4-D gave a low percentage of rooting from callus of ginseng at 2.0 mg/L, and gave no response at higher concentrations (Table 1A); thus, 2,4-D (alone) was not suitable for inducing re-differentiation in P. ginseng. NAA, used alone, could induce rooting of ginseng from calluses at concentrations of 4.0 mg/L or higher (Table 1B), though the highest percentage of rooting was found at 4.0 mg/L NAA. This, the lowest effective concentration, gave a significantly higher number of roots and significantly greater length of the longest root when compared to other NAA concentrations. The ginseng root formed from the peripheral region of the callus (Fig. 1A) and showed an unsynchronized development (Fig. 1B). Auxin/cytokinin ratios are thought to control plant in vitro morphogenesis, with higher ratios promoting rooting, and lower ratios promoting shooting [26]. Therefore, TDZ was used to modulate the auxin/cytokinin ratios and thus induce rooting of ginseng. Surprisingly, it was found that only when the concentration of NAA was higher than TDZ could rooting be induced from P. ginseng callus (Table 1C). Among the series of combinations of NAA and TDZ, the highest rooting percentage (75%) was found at 10 mg/L NAA combined with 0.01 mg/L TDZ, as shown in Table 1C. The higher TDZ concentration (0.1 mg/L) increased the number of roots approximately six-fold, but with a significantly decreased percentage of rooting (30% vs 75%) of ginseng callus. NAA, used alone, at concentrations of 4.0 mg/L was used for subsequent work.

Table 1.

The effect of (A) 2,4-D, (B) NAA and (C) NAA and TDZ on adventitious root formation from callus of Panax ginseng. Data evaluation in all the experiments was according to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the significant differences among the treatments were compared using the Duncan's multiple range test (DMRT) with a 0.05 level of probability [28].

|

Table 1A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-D (mg/L) | Percentage of rooting (%)∗ | Number of roots | Length of the longest root (cm) |

| 0 | 0 | – | – |

| 2.0 | 5 | 4.5 ± 1.5 | 0.45 ± 0.15 |

| 4.0 | 0 | – | – |

| 6.0 | 0 | – | – |

| 8.0 | 0 | – | – |

| 10.0 | 0 | – | – |

|

Table 1B | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NAA (mg/L) | Percentage of rooting (%)∗ | Number of roots | Length of the longest root (cm) |

| 0 | 0 | – | – |

| 2.0 | 0 | – | – |

| 4.0 | 40.0 | 11.0 ± 0.5a∗∗ | 1.85 ± 0.40a |

| 6.0 | 35.0 | 6.3 ± 0.8b | 0.94 ± 0.24b |

| 8.0 | 10.0 | 2.3 ± 1.4c | 0.88 ± 0.14b |

| 10.0 | 10.0 | 1.0± 0c | 0.28 ± 0.26c |

|

Table 1C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA (mg/L) | TDZ (mg/L) | Percentage of rooting (%)∗ | Number of roots | Length of the longest root (cm) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| 10.0 | 0.01 | 75.0 | 2.5 ± 1.0b∗∗ | 0.65 ± 0.23a |

| 10.0 | 0.1 | 30.0 | 6.3 ± 0.8a | 0.73 ± 0.23a |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0 | – | |

| 0.1 | 10.0 | 0 | – | |

| 0.01 | 10.0 | 0 | – | |

∗Twenty replicates were tested for each treatment.

∗∗According to DMRT (P ≤ 0.05), the means ± standard errors within a column that followed by the same letter were regarded as not significantly different.

Fig. 1.

Adventitious root formation from callus of Panax ginseng. (A) Root formation from callus after one month of culture (Bar = 0.5 cm). (B) Root formation from callus after two months of culture (Bar = 0.2 cm).

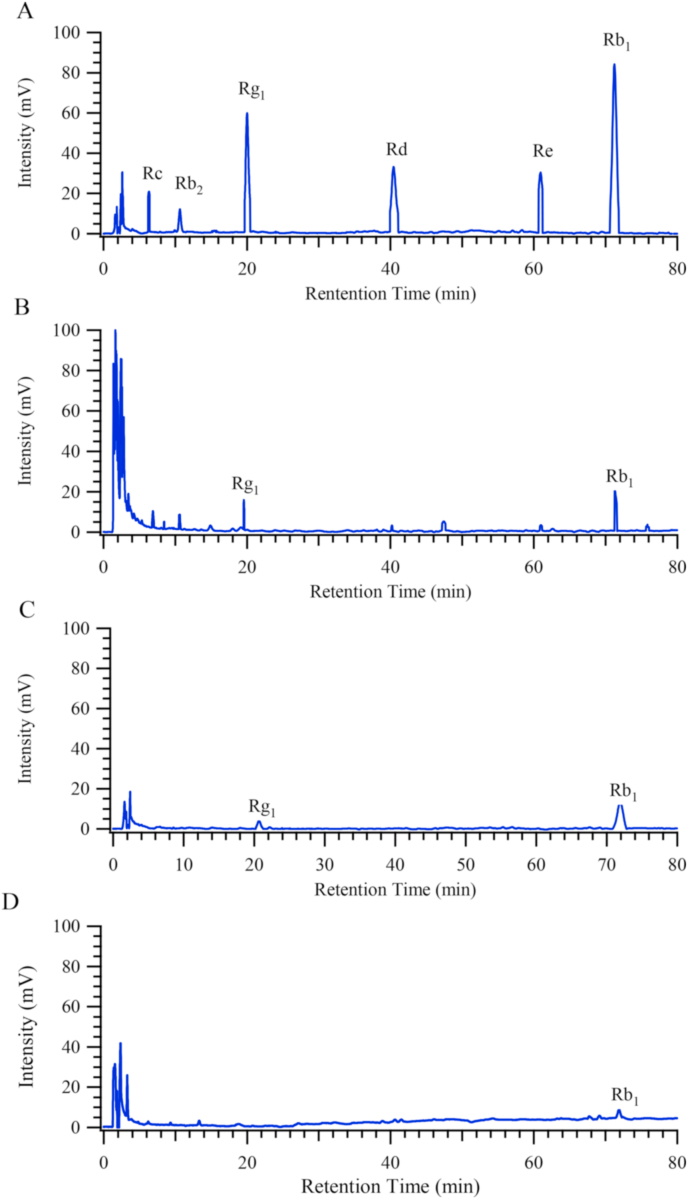

Magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer particles were synthesized using ginsenoside Rb1 as described in the Experimental section, above. The characterization of MMIPs is shown in Fig. S2 and discussed in the Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI S2). HPLC was used to quantify ginsenoside binding to the MMIPs. Fig. 2A shows HPLC of a set of ginsenoside standards; ginsenosides Rc, Rb2, Rg1, Rd, Re and Rb1 were eluted at 6.35, 10.65, 20.01, 40.42, 60.96 and 71.22 min. The crude extract of dried ginseng roots was found to have almost all of them, Fig. 2B, but has higher concentrations of ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 at 50–60 mg/mL (vide infra, Fig. 3A). Fig. 2C shows the HPLC of the extract washed off MMIPs, indicating the presence of ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1. In contrast, the eluate from the MNIPs were found to contain only a small amount of ginsenoside Rb1 (from non-specific binding); Fig. 2D.

Fig. 2.

HPLC retention of (A) ginsenoside standards; (B) extract of ginseng roots; further extraction with (C) MMIPs or (D) MNIPs.

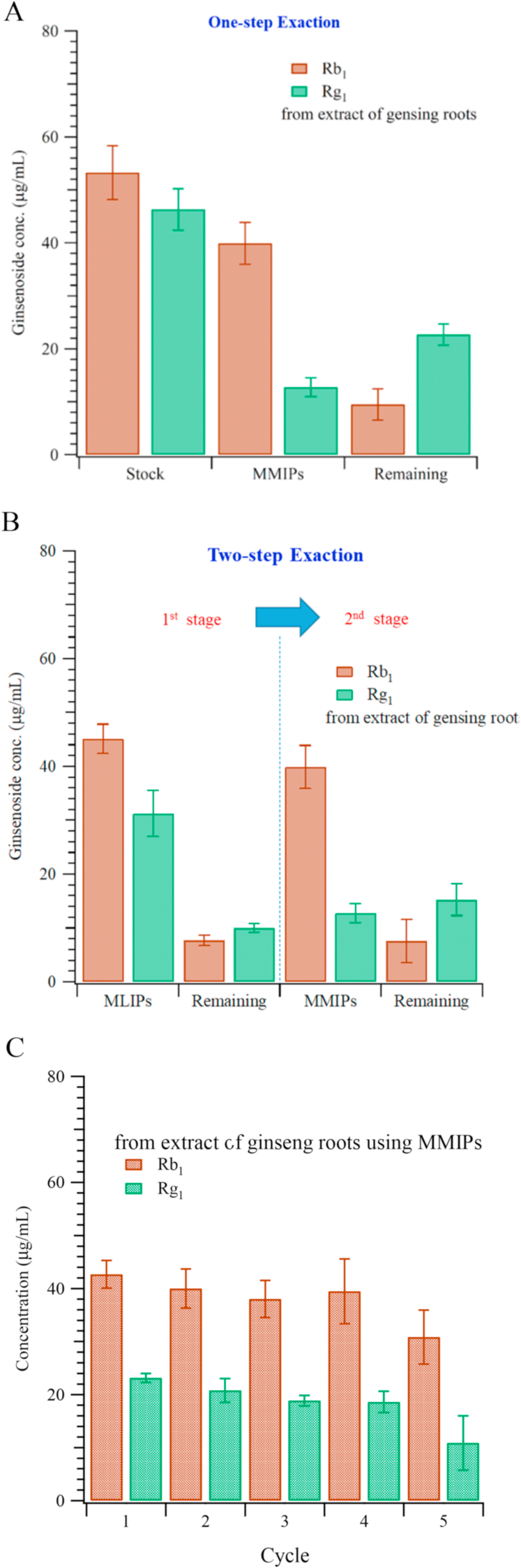

Fig. 3.

Concentration of Rg1 and Rb1 in the extract of ginseng callus (“Stock”), recovered after extraction with MMIPs, and remaining in the stock after the extraction. (A) Single-step extraction using Rb1-imprinted MMIPs; (B) two-step extraction using lanosterol-imprinted MMIPs in the first step. (C) The reusability of the MMIPs, showing good reproducibility for four cycles.

The results of the one-step extraction method (using only MMIPs for the extraction from ginseng root stock) is shown in Fig. 3A. The bound ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 were washed off from MMIPs (templated with Rb1) with vortex mixing for 10 min, recovering about 74.9 ± 7.5% and 27.5 ± 3.8% of the stock concentrations, respectively. 17.8 ± 5.5% of Rb1 and 53.0 ± 3.8% of Rg1 were found to remain in the stock; the remainder represents bound ginsenosides that could not be washed off. A two-step extraction method was also studied, in which MLIPs (using lanosterol, a ginsenoside analogue, as template) were employed for the first extraction step, and then the wash was further extracted with ginsenoside MMIPs. Results are shown in Fig. 3B. Interestingly, imprinting with the ginsenoside Rb1 gives about 80% of the efficiency obtained using lanosterol as the template molecule [27]. The final extracted amount of the ginsenoside Rb1 using the MMIPs (i.e. ginsenoside Rb1 as the template) is almost the same in two-step extraction; however, the extracted amount of Rg1 was dramatically reduced. Fig. 3C shows the reusability of the MMIPs through five cycles. There was a noticeable deterioration in performance in the fifth cycle, but performance remained good through the first four.

In this study, cardiomyocytes were treated with apoptosis-inducing cobalt chloride (CoCl2), and then JC-1 was used to monitor mitochondrial health and recovery, with or without the delivery of ginsenosides. Fig. 4A–D shows the staining of H9c2 cells with JC-1 dye. Fig. 4A and B are controls showing H9c2 cells treated with 30 μg/mL of CoCl2; the green and red indicate the monomeric and aggregated JC-1, respectively. Healthy mitochondrial membrane potential is accompanied by a larger proportion of JC-1 in the aggregated, red form. Mitochondrial membrane potential was decreased with the CoCl2 treatment, and more monomeric JC-1 (green) was found. After the administration of the MMIPs or the MNIPs with ginseng root extract, cells were stained with JC-1 on the 2nd day, shown in Fig. 4C and D, respectively. Cardiomyocytes treated with ginsenoside-loaded MMIPs showed healthier mitochondria (more JC-1 aggregates, Fig. 4C), while cells treated with MNIPs showed less recovery, Fig. 4D. The cellular viability (percentage of live cells, normalized to day 0) is shown in Fig. 4E. Viability after adding CoCl2 was about 60% on the first day, with very small increases in cell numbers over the following days. When MMIPs with ginseng roots extract were added on the 2nd day, cell growth largely recovered, with about 91% of the number of live cells (compared with controls) on the 5th day. The non-imprinted nanoparticles had a much weaker (though still beneficial) effect, likely owing to non-specific binding of ginsenosides. The ratio of JC-1 monomer fluorescence (green) to aggregate fluorescence (red) is plotted in Fig. 4F. This figure shows clearly the protective effect of MMIPs with bound ginsenosides on mitochondrial membrane potential in H9c2 cells; on day 5, the membrane potential, as assayed by the fluorescence ratio, is nearly the same for cells treated with CoCl2 and MMIPs as for healthy control cells. As with viability, non-imprinted MNIPs had only slight beneficial effects.

Fig. 4.

Images of cell apoptosis of (A) H9c2 cells, which were (B) pre-treated with 30 mg/mL CoCl2 and then with added (C) MMIPs; (D) MNIPs, both with bound ginsenosides from ginseng root extract. (E) Cellular viability and (F) mitochondrial damage (as assessed by the JC-1 green: red ratio) in H9c2 cells in the abovementioned conditions.

4. Conclusions

The extraction and cellular delivery of bioactive molecules (e.g. ginsenosides) are of great interest in targeted cellular therapies. Conventional approaches to extraction of bioactive molecules may require toxic organic solvents or expensive or time-consuming concentration procedures. Extraction with molecularly imprinted polymers may overcome both problems; encapsulation of magnetic nanoparticles further facilitates extraction and manipulation of MIPs. This work demonstrated not only the induction of adventitious roots from ginseng callus, but also the effective imprinting of ginsenoside Rb1 into magnetic nanoparticles (MMIPs), and showed that the particles could be used for the extraction of ginsenosides from ginseng root extracts. The ginsenoside-loaded MMIPs were then shown to have protective effects on mitochondrial membrane potential and cellular viability for H9c2 cells treated with CoCl2 to mimic hypoxia injury. These encouraging results suggest that extraction and delivery of ginsenosides using MIPs may have important therapeutic and healthcare applications.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to appreciate the Ministry of Science and Technology of ROC under Contract nos.: MOST 106-2221-E-214-038, MOST 107-2221-E-214-017, MOST 108-2923-I-390-001-MY3, MOST 109-2314-B-390-001-MY3, MOST 110-2221-E-214-012 and the Zuoying Branch of Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital under Contract no. KAFGH-ZY_A_111003.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2022.01.005.

Contributor Information

Jen-Tsung Chen, Email: jentsung@nuk.edu.tw.

Mei-Hwa Lee, Email: meihwalee@ntu.edu.tw, mhlee@isu.edu.tw.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: The supplementary data to this article: Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) S1 and S2.

References

- 1.Neri M., Riezzo I., Pascale N., Pomara C., Turillazzi E. Ischemia/reperfusion injury following acute myocardial infarction: a critical issue for clinicians and forensic pathologists. Mediat Inflamm. 2017;2017:7018393. doi: 10.1155/2017/7018393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano R., Naghavi M., Foreman K., Lim S., Shibuya K., Aboyans V., et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurian G.A., Rajagopal R., Vedantham S., Rajesh M. The role of oxidative stress in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury and remodeling: revisited. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:1656450. doi: 10.1155/2016/1656450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z., Su G., Zhang Z., Dong H., Wang Y., Zhao H., et al. 25-Hydroxyl-protopanaxatriol protects against H(2)O(2)-induced H9c2 cardiomyocytes injury via PI3K/Akt pathway and apoptotic protein down-regulation. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2018;99:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen L.P. Ginsenosides: chemistry, biosynthesis, analysis, and potential health effects. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2008;55:1–99. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4526(08)00401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung K.W., Wong A.S.-T. Pharmacology of ginsenosides: a literature review. Chin Med. 2010;5(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho J., Park W., Lee S., Ahn W., Lee Y. Ginsenoside-Rb1 from Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer activates estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta, independent of ligand binding. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(7):3510–3515. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hou Y.-L., Tsai Y.-H., Lin Y.-H., Chao J.C.J. Ginseng extract and ginsenoside Rb1 attenuate carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in rats. BMC Compl Alternative Med. 2014;14(1):415. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X., Chen L., Liu M., Zhang H., Huang S., Xiong Y., et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 and Rd remarkably inhibited the hepatic uptake of ophiopogonin D in shenmai injection mediated by OATPs/oatps. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:957. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li F., Wu Z., Sui X. Biotransformation of ginsenoside Rb1 with wild Cordyceps sinensis and Ascomycota sp. and its antihyperlipidemic effects on the diet-induced cholesterol of zebrafish. J Food Biochem. 2020;44(6) doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou W., Chai H., Lin P.H., Lumsden A.B., Yao Q., Chen C. Ginsenoside Rb1 blocks homocysteine-induced endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(5):861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X., Chai H., Yao Q., Chen C. Molecular mechanisms of HIV protease inhibitor-induced endothelial dysfunction. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;44(5):493–499. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180322542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S.E., Park Y.S. Korean Red Ginseng water extract inhibits COX-2 expression by suppressing p38 in acrolein-treated human endothelial cells. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2014;38(1):34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang B., Matsuda S., Tanaka J., Tateishi N., Maeda N., Wen T.-C., et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 prevents image navigation disability, cortical infarction, and thalamic degeneration in rats with focal cerebral ischemia. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1998;7(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3057(98)80015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujita K., Hakuba N., Hata R., Morizane I., Yoshida T., Shudou M., et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 protects against damage to the spiral ganglion cells after cochlear ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2007;415(2):113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan Q.-L., Yang C.-X., Xu P., Gao X.-Q., Deng L., Chen P., et al. Neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on transient cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1167:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakanaka M., Zhu P., Zhang B., Wen T.-C., Cao F., Ma Y.-J., et al. Intravenous infusion of dihydroginsenoside Rb1 prevents compressive spinal cord injury and ischemic brain damage through upregulation of VEGF and Bcl-XL. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(6):1037–1054. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ai Q., Sun G., Luo Y., Dong X., Hu R., Meng X., et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 prevents hypoxia-reoxygenation-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes via an estrogen receptor-dependent crosstalk among the Akt, JNK, and ERK 1/2 pathways using a label-free quantitative proteomics analysis. RSC Adv. 2015;5(33):26346–26363. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang H., Wang X., Ma Y., Shi Y. The effect of ginsenoside RB1, diazoxide, and 5-hydroxydecanoate on hypoxia-reoxygenation injury of H9C2 cardiomyocytes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:6046405. doi: 10.1155/2019/6046405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee M.-H., Thomas J.L., Wang H.-Y., Chang C.-C., Lin C.-C., Lin H.-Y. Extraction of resveratrol from polygonum cuspidatum with magnetic orcinol-imprinted poly(ethylene-co-vinyl alcohol) composite particles and their in vitro suppression of human osteogenic sarcoma (HOS) cell line. J Mater Chem. 2012;22(47):24644–24651. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee M.-H., Thomas J.L., Liao C.-L., Jurcevic S., Crnogorac-Jurcevic T., Lin H.-Y. Epitope recognition of peptide-imprinted polymers for Regenerating protein 1 (REG1) Separ Purif Technol. 2018;192:213–219. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee M.-H., Thomas J.L., Ho M.-H., Yuan C., Lin H.-Y. Synthesis of magnetic molecularly imprinted poly (ethylene-co-vinyl alcohol) nanoparticles and their uses in the extraction and sensing of target molecules in urine. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2010;2(6):1729–1736. doi: 10.1021/am100227r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee M.-H., Thomas J.L., Chen Y.-C., Wang H.-Y., Lin H.-Y. Hydrolysis of magnetic amylase-imprinted poly (ethylene-co-vinyl alcohol) composite nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2012;4(2):916–921. doi: 10.1021/am201576y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen S.L., Yang C.T., Yang Z.L., Guo R.X., Meng J.L., Cui Y., et al. Hydrogen sulphide protects H9c2 cells against chemical hypoxia-induced injury. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37(3):316–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi Y.-N., Zhang X.-Q., Hu Z.-Y., Zhang C.-J., Liao D.-F., Huang H.-L., et al. Genistein protects h9c2 cardiomyocytes against chemical hypoxia-induced injury via inhibition of apoptosis. Pharmacology. 2019;103(5–6):282–290. doi: 10.1159/000497061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skoog F., Miller C., editors. Chemical regulation of growth and organ formation in plant tissues cultured. Vitro Symp Soc Exp Biol; 1957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu K.-H., Lin H.-Y., Thomas J.L., Shih Y.-P., Chen J.-T., Lee M.-H. Extraction of ginsenosides from the Panax ginseng callus using magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer composite nanoparticles. Ind Crop Prod. 2021;163:113291–113299. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan D.B. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics. 1955;11(1):1–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.