Abstract

Background

Few studies reported the therapeutic effect of Korean Red Ginseng (KRG) in lung inflammatory diseases. However, the anti-inflammatory role and underlying molecular in cadmium-induced lung injury have been poorly understood, directly linked to chronic lung diseases (CLDs): chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer etc. Therefore, in this study we aim to investigate the therapeutic activities of water extract of KRG (KRG-WE) in mouse cadmium-induced lung injury model.

Method

The anti-inflammatory roles and underlying mechanisms of KRG-WE were evaluated in vitro under cadmium-stimulated lung epithelial cells (A549) and HEK293T cell line and in vivo in cadmium-induced lung injury mouse model using semi-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), luciferase assay, immunoblotting, and FACS.

Results

KRG-WE strongly ameliorated the symptoms of CdSO4-induced lung injury in mice according to total cell number in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and severity scores as well as cytokine levels. KRG-WE significantly suppressed the upregulation of inflammatory signaling comprising mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and their upstream enzymes. In in vitro study, KRG-WE suppressed expression of interleukin (IL)-6, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, and IL-8 while promoting recovery in CdSO4-treated A549 cells. Similarly, KRG-WE reduced phosphorylation of MAPK and c-Jun/c-Fos in cadmium-exposed A549 cells.

Conclusion

KRG-WE was found to attenuate symptoms of cadmium-induced lung injury and reduce the expression of inflammatory genes by suppression of MAPK/AP-1-mediated pathway.

Keywords: Korean Red Ginseng, Panax ginseng, Lung injury, Cadmium, Anti-inflammatory activity. AP-1

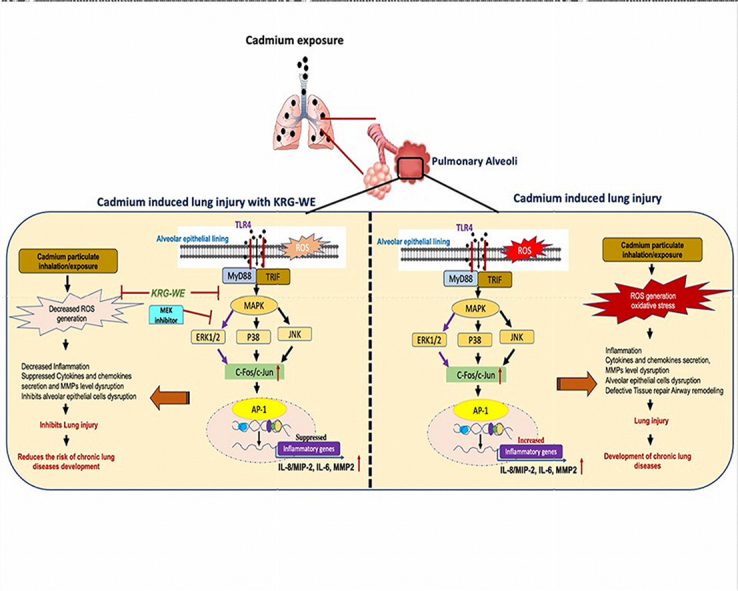

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Lung epithelial cells are the first line of defense against exogenous pollutants and pathogens [1,2] that can lead to the development of various chronic lung inflammatory diseases (CLDs) [3,4]. Tobacco or cigarette smoking is the major etiological factor of CLDs such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cancer [5], with the primary active therapy being smoking cessation. It would be beneficial if we can understand the underlying patho-mechanism and their relationship to elements present in cigarette or tobacco which are responsible for disease development. Cadmium, present in cigarette/tobacco [6,7], is currently ranked 7th on the priority list of hazardous substances by the Agency of Toxic Substances and Disease Registry [8]. Studies reported that pulmonary absorption of inhaled cadmium can reach 80% compared with 5% when orally ingested [9]. Importantly, cadmium is highly present in cigarette smoke (i.e. up to 2–4 μg/cigarette) and fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) [10,11]. Exposure to cadmium has been directly linked to CLDs [3,11].

Studies shows that cadmium induces inflammation and oxidative stress, resulting in lung damage, secretion of proinflammatory cytokines from lung epithelial and extracellular matrix degradation [12]. Sundblad [13] et al., reported increased extracellular cadmium levels in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of long-term smokers of COPD patients [13]. Study also demonstrated the association between the local cadmium and dysregulation in innate immunity in the lungs, thereby elevating inflammatory marker levels such as transcription of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in alveolar macrophages, cytokines which includes interleukin (IL)-6 and −8 as well as increased neutrophil activity marker matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)- 2 and 9 [13]. Previously, human lung epithelial cells and mouse models show even low levels of cadmium exposure stimulates IL-6 and -8, secretion by Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [14,15]. Therefore, targeting inflammatory signaling pathways could be an important therapeutic strategy for cadmium-induced lung injury or CLDs, since identification of the critical target cascades in CLDs has not been successful. Thus, herbal drugs and plant-originated compounds have been a thrust area in the search for novel potential mediators.

Panax ginseng and Korean Red Ginseng (KRG) are a traditional Korean medicinal herb since thousands of years [16,17]. KRG is well-known for immune modulation and possesses potential anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory effects and regulates autophagy [18,19]. The therapeutic effect of ginseng extracts against asthma have been well documented [20]. Therefore, we investigate the anti-inflammatory mechanism and therapeutic effect of KRG-water extracts (KRG-WE) in cadmium-induced lung injury by targeting the MAPK/ERK via AP-1 transcription factor. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report showing the pharmacology and therapeutical potential of KRG-WE in cadmium induced lung injury by targeting AP-1 through upstream MAPK/ERK kinase pathway in vitro and in vivo.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

KRG-WE was obtained from Korean Ginseng Corporation (Daejeon, Korea). Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol,2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), Cadmium sulfate and an ERK inhibitor (U0126) were purchased from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Biotechnics Research (Lake Forest, CA, USA), and Ham's F–12K (Kaighn's) medium, Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 (RPMI 1640) and Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) were obtained from HyClone (Grand Island, NY, USA). The lung alveolar epithelial cell line (A549) (No. KCLB-10185) was acquired from the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Seoul, Korea) and human embryonic kidney cell line (HEK293T) (No. CRL-3216) was purchased from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA). The AP-1 binding site-containing luciferase construct was used as reported previously [21]. Antibodies (phospho-specific and total) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA).

2.2. Preparation of KRG-WE and analysis of ginsenosides

Stock solutions (100 mg/mL) of KRG-WE were prepared in PBS and diluted in media for in vitro studies. For in vivo experiment, KEG-WE was suspended in 0.5% Na CMC. For ginsenoside analysis, the UPLC-photo diode array (PDA) system (Waters Co., Milford, MA, USA) was used to detect 11 ginsenosides, as reported previously [22,23]. Supplementary Fig. 1 indicates the separation pattern of ginsenosides observed by HPLC analysis.

2.3. Cell culture

A549 were maintained in F12–K supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. HEK293T cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS. Both cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C supplemented with 5% CO2.

2.4. Induction of cadmium-treated lung injury model

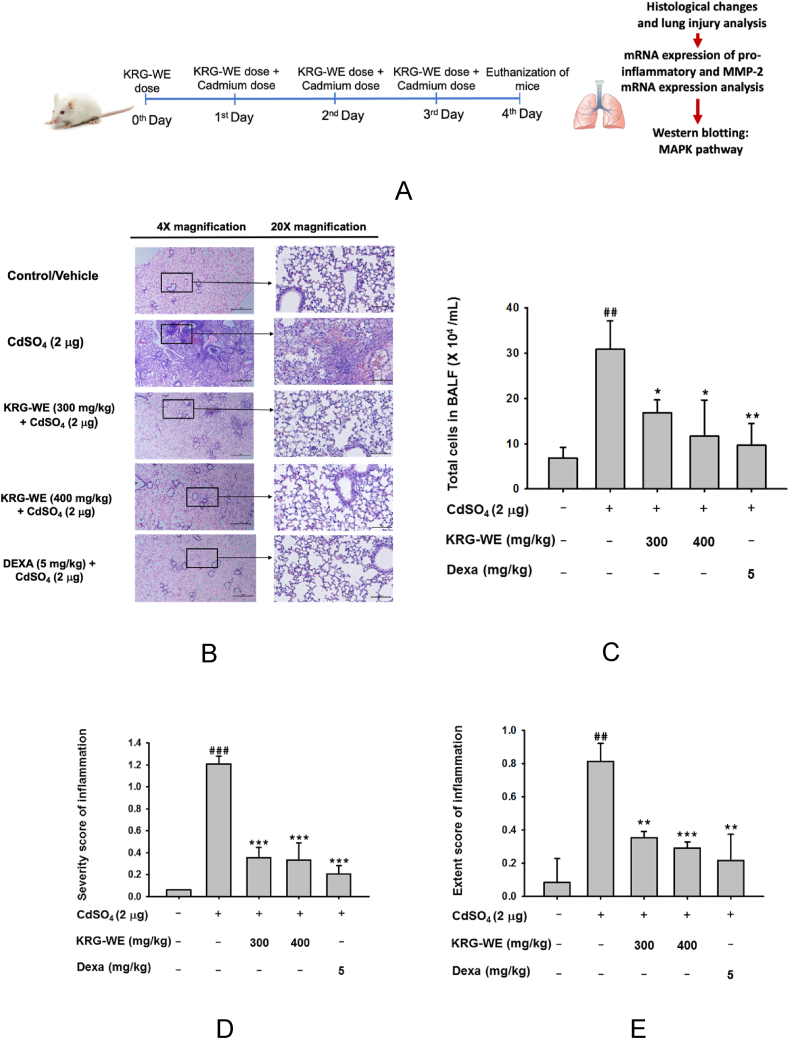

Balb/c (age = 8-weeks, male, 20–23 g) obtained from Orient-Bio (Sungnam, Korea) were kept in SKKU animal holding facility under pathogen-free conditions at 21–23 °C under constant humidity (40–60%) and 12-h light–dark cycle. Food and water were given as required. The mice were categorized into 5 study groups of 5 mice/group: control/vehicle group, cadmium (2 μg) group, KRG-WE (300 mg/kg) + cadmium, KRG-WE (400 mg/kg) + cadmium group, and DEXA (5 mg/kg) + cadmium group. The control group of mice were administered saline orally using gavage needle. Mice in the KRG-WE + cadmium groups were given the KRG-WE 300 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg by orally, respectively twice before 1 h of cadmium treatment and once after cadmium treatment for 3 d. The concentration of KRG-WE (300 and 400 mg/kg) were selected as previously demonstrated [24,25]. Mice in the DEXA + cadmium group received DEXA by oral administration twice before 1 h of cadmium treatment and once after cadmium treatment for 3 days (Fig. 1). Cadmium group mice were instilled intranasally with 2 μg CdSO4 in 50 μL PBS twice for 3 d as previously demonstrated [8]. Before cadmium treatment, all mice were anesthetized. Mice were sacrificed after 3 d. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and lung samples were isolated. Total cell count was performed from BALF using hemocytometer.

Fig. 1.

Anti-inflammatory effect of KRG-WE on cadmium-induced lung injury. (A) Schematic strategy of KRG-WE oral administration and cadmium (CdSO4) intranasal instillation in mice lung. (B) Histology assessment was performed by H&E-staining to visualize the suppressive effect of KRG-WE (300 and 400 mg/kg) in cadmium induced lung in mice after 3 d of instillation, scale bar represents 20 μm. (C) Total cells in BALF were counted by a cell counter. (D and E) Effect of KRG-WE in CdSO4-induced lung injury was evaluated by scoring the severity (D) and extent (E) of histological injury. (F and G) The mRNA expression levels of IL-6, MIP-2 (IL-8), MMP-2, c-Fos, and c-Jun were determined in CdSO4-induced mice lung tissues using qPCR. (H and I) The total and phospho-protein levels of MAPKs (ERK, p38, and JNK) and their upstream enzymes (MEK1/2, MKK3/6, and MKK4) was evaluated in mice lung tissues using immunoblotting analysis. Data is expressed as the mean ± SD of an experiments done with 5 biological replicates. ##: P < 0.01 and ###: P < 0.001 compared to normal group, and ∗: P < 0.05, ∗∗: P < 0.01, ∗∗∗: P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗: P < 0.0001 compared to control group.

2.5. Histology assessment

Mice upper lobes of right lungs were excised and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for fixation overnight. The samples were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, examined under a brightfield microscope (Optinity microscope, #KI-3000F), and analyzed using Optiview. Semi-quantitative method was used for inflammatory injury scoring as previously described [26], summarized in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2

2.6. Cell viability assay

The viability of A549 and HEK293T cells was determined using MTT assay [27]. After pre-incubation for 18 h, the cells were treated with different concentrations of KRG-WE (25–400 μg/mL) in presence and absence of cadmium and incubated for an additional 24 h. The cytotoxicity of the KRG-WE was evaluated using MTT assay as described previously [28].

2.7. Oxidative stress assessment

Oxidative stress was determined by using 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′, 7’ dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA, Sigma Aldrich, USA). A549 cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in 12 well plates and incubated for 24 h followed by pre-treatment with KRG-WE (300 and 400 μg/mL) for 30 min and treatment with cadmium (5 μM) for 6 h. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated (37 °C, 5% CO2) with 10 μM H2DCFDA-containing media for 30 min in darkness. The H2DCFDA was removed by washing twice with PBS. ROS levels were measured by CytoFLEX Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

2.8. Semi-quantitative (RT-PCR) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from mice lung tissues or A549 cells using TRIzol Reagent based on manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (1 μg) using MMLV RTase (SuperBio, Daejeon, Korea). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and Semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed to quantify the mRNA expression as previously described [29]. All primers sequences are listed in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4

2.9. Plasmid transfection and luciferase reporter gene activity assay

HEK293T cells (1 × 106 cells/ml in 24-well plates) were transfected with 1 μg of plasmid containing β-galactosidase and AP-1-Luc in the presence or absence of MyD88 and TRIF using the polyethyleneimine (PEI) reagent. KRG treatment was performed for 12 h before harvesting the cells. Luciferase assays were performed using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), as previously reported [30].

2.10. Protein lysate preparation and immunoblotting analysis

The lysates of lower part of the right lungs and A549 cells (2 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plate) were prepared as previously described [31] followed by immunoblotting analysis using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and then immunoblotting with antibodies (total and phosphorylated) as previously reported [30]. The bands were documented.

2.11. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent experiments. Mann-Whitney tests were utilized for comparison. The computer program SPSS (version 26, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical tests, and a p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of KRG-WE in cadmium-induced lung injury in mice

We investigated the anti-inflammatory effect of KRG-WE in a cadmium-induced lung injury mouse model. The histology data of cadmium-induced lung injury (Fig. 1B) shows significant pathological changes in bronchiolar region and throughout alveoli, inflammatory cells penetration within alveoli and pulmonary parenchyma were detected, whereas control mice show normal lung morphology. However, KRG-WE pre-treated group mice lungs showed significantly less morphological changes. The inflammatory score indicated the extent and severity of inflammatory cells and reduction of lung injury in KRG-WE pre-treated cadmium-induced mice lungs (Fig. 1D and E). Additionally, significant reduction of total inflammatory cells count was observed in KRG-WE pre-treated mice lungs (Fig. 1C). Further, we observed that mRNA levels of IL-6, MIP-2 (homolog of IL-8), and MMP-2 were increased significantly in cadmium-induced mice lungs compared to control group and were significantly downregulated by oral KRG-WE groups (300 and 400 mg/kg) (Fig. 1F). DEXA (5 mg/kg) was also used as a reference drug and showed inhibition of IL-6, MIP-2, and MMP-2 mRNA expression compared to cadmium-induced mice lung. c-Fos and c-Jun mRNA expression (Fig. 1G) was markedly inhibited in KRG-WE-treated groups (300 and 400 mg/kg) and DEXA group compared to cadmium-induced mice lung. Further, immunoblotting analysis was performed to analyze the KRG-WE inhibition of MAPK signaling in cadmium-induced lung injury in mice. As demonstrated in (Fig. 1H and I), mice challenged with cadmium showed significant increase in phosphorylation of ERK, p38, and JNK and their upstream MEK1/2, MKK3/6, and MKK4 phosphorylation compared to control group and were significantly inhibited in KRG-WE groups. These results imply that KRG-WE has a strong potential anti-inflammatory effect against cadmium-induced lung injury.

3.2. Effect of KRG-WE in cadmium-treated A549 cells

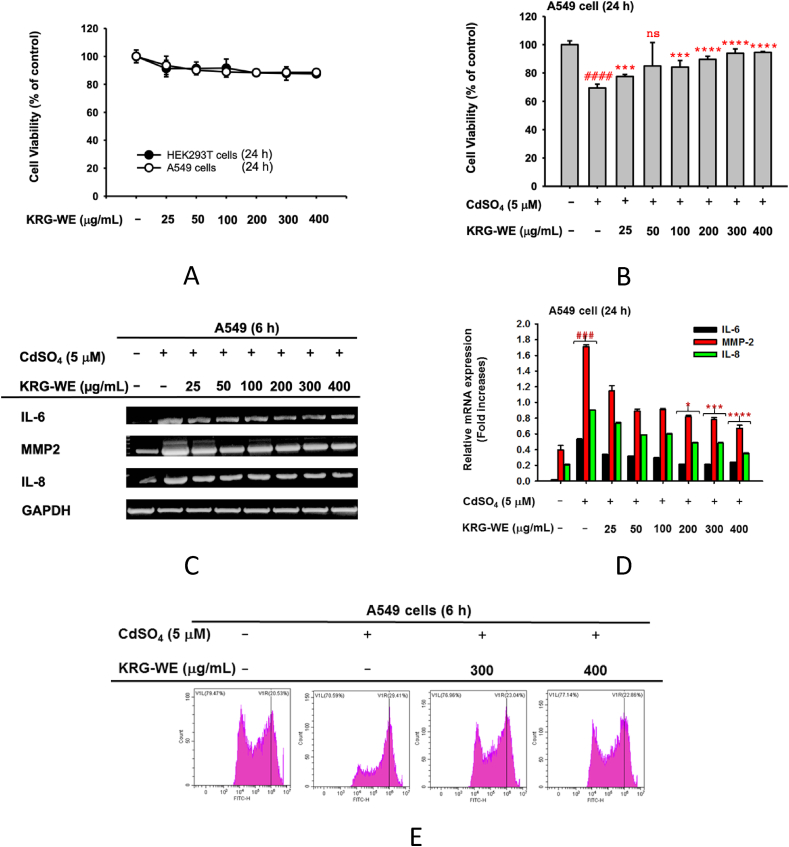

We determined the effect of KRG-WE on the viability of A549 and HEK293T cells by MTT assay. KRG-WE dosage 25–400 μg/mL did not significantly alter the viability of these cells (Fig. 2A) and suppressed CdSO4 (5 μM)-induced cytotoxicity of A549 cells (Fig. 2B). We further investigated the effect of KRG-WE (25–400 μg/mL) on IL-8, IL-6, and MMP-2 expression in A549 cells treated with CdSO4 by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The mRNA expression levels of IL-8, IL-6, and MMP-2 significantly decreased in the presence of KRG-WE at 300 and 400 μg/mL (Fig. 2C and D). Therefore, in subsequent experiments, we treated the cells with 300 and 400 μg/mL. Since cadmium can induce cell death via ROS production in cells [32,33], we examined whether KRG-WE can suppress ROS production in A549 cells under CdSO4 induction. As Fig. 2E shows, KRG-WE dose-dependently inhibited CdSO4-induced ROS generation (Fig. 2E). Treatment with 300 and 400 μg/mL of KRG-WE decreased ROS generation by 23.04% and 22.86%, respectively, compared with cadmium-induced A549 cells (29.41%). Therefore, the KRG-WE also has antioxidants effects in lung alveolar epithelial cell lines (A549).

Fig. 2.

Anti-inflammatory effect of KRG-WE in cadmium-treated A549 cells. (A) Effect of KRG-WE (0–400 μg/mL) on viability of A549 and HEK293T cells was evaluated by MTT assay. (B) Recovery activity of KRG-WE (0–400 μg/mL) on CdSO4–induced cell death of A549 cells was determined by MTT assay. (C and D) Suppressive effect of KRG-WE (0–400 μg/mL) on the mRNA expression of inflammatory genes was evaluated using semi-quantitative RT-PCR (C) and qPCR. Radical scavenging activity of KRG-WE (300 and 400 μg/mL) on CdSO4–induced ROS generation in A549 cells. ROS levels were determined by flowcytometric analysis. Data is expressed as the mean ± SD of an experiments done with 3 biological replicates. ###: P < 0.001 compared to normal group, and ∗: P < 0.05, ∗∗∗: P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗: P < 0.0001 compared to control group.

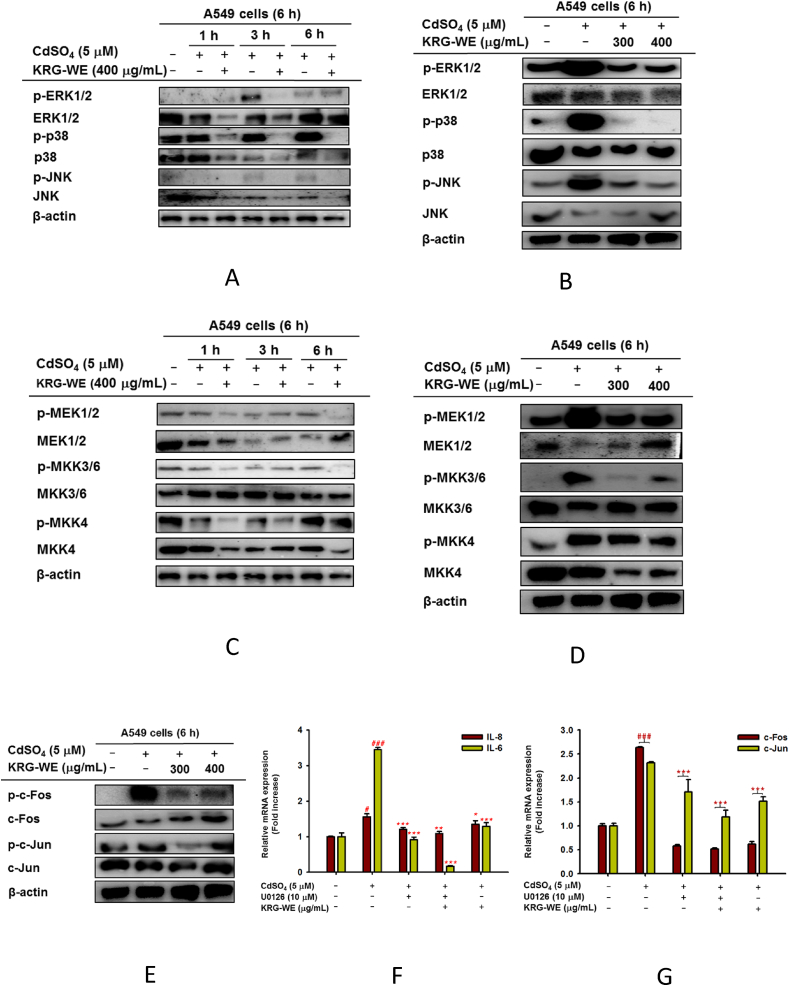

3.3. Effect of KRG-WE on upstream signaling of AP-1 activation in cadmium-treated A549 cells

MAPK phosphorylation plays a crucial role in regulating the cadmium-induced lung inflammatory responses [8,34]. Our in vivo results also showed that KRG-WE can inhibit MAPK phosphorylation in cadmium-induced mice lung injury (Fig. 1H and I, relative density summarized in supplementary Fig.4A). To confirm this, we further performed immunoblotting analysis on MAPK signaling in vitro. Indeed, we also observed that KRG-WE pretreatment significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of ERK, p38, and JNK, time-dependently (1, 3, and 6 h) (Fig. 3A, relative density summarized in supplementary Fig.5A) and dose-dependently (300 and 400 μg/mL at 6 h) (Fig. 3B, relative density summarized in supplementary Fig.5B). KRG-WE also suppressed the phosphorylation levels of their upstream enzymes such as MEK1/2, MKK3/6, and MKK4, time-dependently and dose-dependently (Fig. 3C and D, relative density summarized in supplementary Fig. 5A and 5C).

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effect of KRG-WE on activation of AP-1-related signaling pathway. (A–E) Total and phospho-protein levels of ERK1/2, p38, JNK, MEK1/2, MEK3/6, MKK4, and β-actin in CdSO4–treated A549 cell lysates were determined by immunoblotting analysis. (F and G) Effect of KRG-WE on the mRNA expression of inflammatory genes, IL-8 and IL-6 (F), and AP-1 subunits, c-Fos and c-Jun (G) in CdSO4–treated A549 cells using qPCR. Data is expressed as the mean ± SD of an experiments done with 3 biological replicates. ###: P < 0.001 compared to normal group, and ∗: P < 0.05, ∗∗: P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗: P < 0.001 compared to control group.

We further investigated AP-1 suppression by KRG-WE through examining c-Fos and c-Jun activation level. As Fig. 3E shows, KRG-WE (300 and 400 μg/mL at 6 h) dose-dependently blocked the phospho-protein levels of c-Fos and c-Jun in cadmium-treated A549 cells (Fig. 3E, relative density summarized in supplementary Fig.5D). To confirm that KRG-WE can block AP-1 activation, we performed an AP-1-mediated luciferase reporter gene assay using HEK293T cells transfected with adapter molecules MyD88 and TRIF during exposure of KRG-WE (300 and 400 μg/mL). As Supplementary Fig. 2A and B depict, KRG-WE significantly reduced AP-1-mediated luciferase activity.

Studies reported that production of IL-8 and IL-6 by human lung epithelial cells are regulated by ERK1/2 [8]. In addition, MAPK has been demonstrated as a regulator of AP-1 transcription factor and linked to proinflammatory gene expression [35]. Since KRG displayed suppression of MAPK, whether KRG-WE-targeted MAPK is a critical target in suppression of cadmium-induced lung injury was investigated. As expected, it was found that U0126, an ERK inhibitor, more efficiently suppresses the mRNA levels of IL-6, IL-8, c-Fos, and c-Jun in cadmium-induced A549 cells (Fig. 3F and G).

4. Discussion

As it is well-known that KRG has immune modulation and possesses potential anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory effects and regulates autophagy [18,19]. Few clinical studies reported that Panax ginseng (G115) has inhibitory effect of acute exacerbation and improving quality of life in COPD patients, but they are not significant [36,37]. In addition, previously, inhibition of ginsenoside Re showed significant suppressive effect against LPS-induced lung inflammation via MAPKs/NF- kB/c-Fos signaling pathway [38]. As we have mentioned above, cadmium is one of the hazardous elements which significantly present in cigarette/tobacco smoke and in PM2.5 as well and it is highly associated to CLDs [10,11]. However, the mechanism and anti-inflammatory effect of KRG in cadmium-induced lung injury in CLDs is still not reported. Hence, it is more important to understand the mechanism of cadmium induced lung injury and how KRG-WE can mitigate its effect. In this study, we investigated the anti-inflammatory therapeutic effect of KRG-WE and its mechanism in cadmium-induced lung injury in CLDs development in vitro and in vivo. Studies show that cadmium is a potent activator of IL-8 and IL-6 in human lung epithelial cells as well in vivo [8]. Additionally, elevation of MMP-2 expression is associated with COPD/emphysema [3]. Our study shows, oral administration of KRG-WE in mice model of cadmium-induced lung injury shows decreased inflammatory cells infiltration and less alveolar damage in their lung section compared to cadmium treated group (Fig. 1A–E). Further, KRG-WE significantly inhibits the expression of IL-6, MIP-2, MMP-2, c-Fos, and c-Jun at the transcriptional level in cadmium-treated lung tissues (Fig. 1F and G). Therefore, KRG-WE can modulate inflammatory responses by inhibiting transcriptional activation of inflammatory genes. Immunoblotting results show that KRG-WE (300 and 400 mg/kg) strongly suppressed the phosphorylation of MAPK pathway compared with cadmium-induced mouse lungs (Fig. 1H and I). DEXA (5 mg/kg) also suppresses both mRNA and protein levels in cadmium-treated lung tissue like KRG-WE.

We further determine the anti-inflammatory effect and molecular mechanism of KRG-WE against lung-injury in cadmium exposure in vitro. Lung epithelial cells are known to be first line barrier and key regulators of inflammatory responses, however aberrant inflammation leads to CLDs [1,2]. Hence, we used human lung alveolar epithelial cells (A549) to determine KRG-WE anti-inflammatory effect and its molecular mechanism against cadmium-exposed lung injury. Since ROS production is important for CLDs [32,33], we determined, KRG-WE suppresses cadmium-induced oxidative stress in A549 cells dose-dependently (Fig. 2E) and cell viability was not affected (Fig. 2A and B). Previously, studies reported that KRG inhibits ROS production in bisphenol A (BPA)-induced inflammation in lung cancer in vitro [39] and in ototoxicity [40]. As we demonstrated above, cadmium is a potent activator of IL-8, IL-6, and MMP-2, which lead to CLDs [3,8]. We observed that KRG-WE has anti-inflammatory effect against cadmium-induced inflammation in A549 cells by inhibiting IL-8, IL-6, and MMP-2 mRNA expression (Fig. 2C and D).

We observed that KRG-WE could block the transcriptional activation of inflammatory genes, so we next determined its targeted transcription factor AP-1. Studies demonstrated that AP-1 is known to influence the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and inflammation [35]. As previously confirmed luciferase reporter gene assay to measure AP-1 activity triggered by TRIF and MyD88 [41,42], we found that KRG-WE inhibits the AP-1 luciferase activity dose-dependently (Supplementary Fig. 2). MyD88 and TRIF are the intracellular proteins recruited by TLR4 receptor which activates MAPK upstream signaling pathway of AP-1 [43]. It has been previously demonstrated that cadmium induces the mucin 8 level in lung airway epithelial cells through TLR4 mediated ERK1/2/MAPK pathway [44]. MAPK might play a key role in anti-inflammatory activity of KRG-WE. Our study demonstrates that KRG-WE inhibits the ERK, p38, and JNK phosphorylation time-dependently (1, 3, and 6 h) and dose-dependently (300 and 400 μg/mL) (Fig. 3A and B) in cadmium-exposed A549 cells. Additionally, the phosphorylation of MEK1/2, MKK4, and MEK3/6, upstream of ERK and p38 and JNK, was also significantly suppressed in cadmium exposure both time- and dose-dependently (Fig. 3C and D). We also determined that KRG-WE (300 and 400 μg/mL) dose-dependently blocked c-Fos and c-Jun phosphorylation in cytosol at 6 h (Fig. 3E), which implies that KRG-WE can inhibit c-Fos and c-Jun nuclear translocation, thereby blocking the AP-1 activation and modulating inflammatory responses. Thus, these results confirm that KRG-WE inhibited MAPK/AP-1 activity in cadmium-induced lung injury. In addition, we determined that inhibition of MEK/ERK1/2 pathway and KRG-WE treated significantly decreased the mRNA expression of IL-8, IL-6, and AP-1 subunits (Fig. 3F and G). Interestingly, we found that KRG-WE with U0126 more efficiently inhibit these proinflammatory cytokines and the c-Fos and c-Jun transcript levels in cadmium-induced A549 cells (Fig. 3F and G). Previous studies reported that production of IL-8 and IL-6 by human lung epithelial cells is regulated by ERK1/2 [8]. In addition, MAPK has been demonstrated as regulators of AP-1 transcription factors and linked to the proinflammatory gene expression [35]. Hence, our data suggests that KRG-WE may have pharmacologically synergistic effect with U0126 against cadmium-induced lung injury.

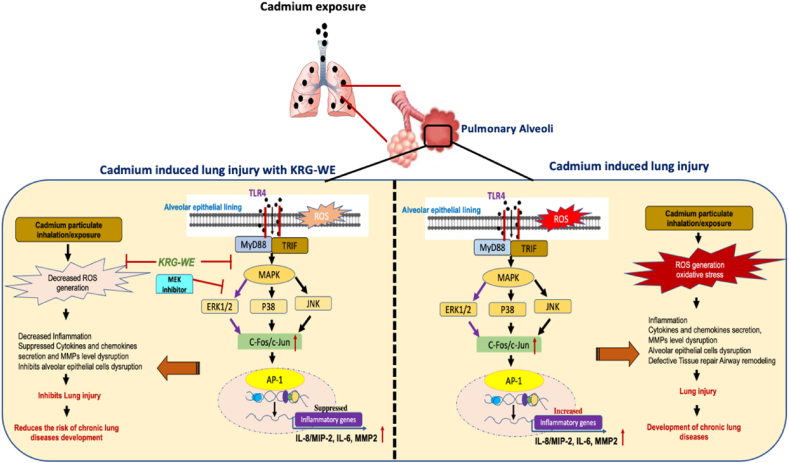

Conclusively, the in vivo and in vitro assays confirmed that KRG-WE significantly reduced cadmium-induced production of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-8) and MMP-2 via MAPK/ERK/AP-1 inactivation, as summarized in Fig. 4. KRG-WE also ameliorated the symptoms of cadmium-induced lung injury in mice. KRG root extract (white ginseng) was previously reported as having anti-inflammatory potential against LPS-induced acute lung injury (ALI)/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) via PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and MAPK signaling pathway [38,45]. Hence, our data strongly suggest that KRG-WE might have anti-inflammatory potential effect against cadmium-induced lung injury in CLDs.

Fig. 4.

Summary of anti-inflammatory mechanisms of KRG-WE in cadmium-induced lung injury.

Author contributions

AM and JYC conceived and designed the experiments; AM, LR, HPL, CKH, HSH, and SAK performed the experiments; AM and JYC analyzed the data; AM and JYC wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (2017R1A6A1A03015642), by the Korean Socieity of Ginseng (2021), and by Korea Basic Science Institute (National research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education. (grant No. 2020R1A6C101A191), Korea.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2022.04.003.

Contributor Information

Ankita Mitra, Email: ankitamitra@skku.edu.

Laily Rahmawati, Email: lyra.enhaihi@gmail.com.

Hwa Pyoung Lee, Email: lhp0507@naver.com.

Seung A. Kim, Email: seung-a26@naver.com.

Chang-Kyun Han, Email: ckhan@kgc.co.kr.

Sun Hee Hyun, Email: shhyun@kgc.co.kr.

Jae Youl Cho, Email: jaecho@skku.edu.

Abbreviation

- AP-1

Activator protein −1

- MAPKs

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

- ERK1/2

Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases 1 and 2

- p38

p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MKK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- IL-18

Interleukin 8

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- MMP-2

matrix metalloproteinase 2

- MIP-2

macrophage inhibitory protein 2

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lee P.-H., Park S., Lee Y.-G., Choi S.-M., An M.-H., Jang A.-S. The impact of environmental pollutants on barrier dysfunction in respiratory disease. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2021;13:850–862. doi: 10.4168/aair.2021.13.6.850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Healy C., Munoz-Wolf N., Strydom J., Faherty L., Williams N.C., Kenny S., Donnelly S.C., Cloonan S.M. Nutritional immunity: the impact of metals on lung immune cells and the airway microbiome during chronic respiratory disease. Respir Res. 2021;22:133. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01722-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirschvink N., Vincke G., Fiévez L., Onclinx C., Wirth D., Belleflamme M., Louis R., Cataldo D., Peck M.J., Gustin P. Repeated cadmium nebulizations induce pulmonary MMP-2 and MMP-9 production and emphysema in rats. Toxicology. 2005;211:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kc R., Shukla S.D., Gautam S.S., Hansbro P.M., O'Toole R.F. The role of environmental exposure to non-cigarette smoke in lung disease. Clin Transl Med. 2018;7:39. doi: 10.1186/s40169-018-0217-2. 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogelmeier C.F., Criner G.J., Martinez F.J., Anzueto A., Barnes P.J., Bourbeau J., Celli B.R., Chen R., Decramer M., Fabbri L.M., Frith P., Halpin D.M., López Varela M.V., Nishimura M., Roche N., Rodriguez-Roisin R., Sin D.D., Singh D., Stockley R., Vestbo J., Wedzicha J.A., Agustí A. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:557–582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan J., Plant J.A., Voulvoulis N., Oates C.J., Ihlenfeld C. Cadmium levels in Europe: implications for human health. Environ Geochem Health. 2010;32:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10653-009-9273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang J., Xiao T., Wang S., Lei J., Zhang M., Gong Y., Li H., Ning Z., He L. High cadmium concentrations in areas with endemic fluorosis: a serious hidden toxin? Chemosphere. 2009;76:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cormet-Boyaka E., Jolivette K., Bonnegarde-Bernard A., Rennolds J., Hassan F., Mehta P., Tridandapani S., Webster-Marketon J., Boyaka P.N. An NF-kappaB-independent and Erk1/2-dependent mechanism controls CXCL8/IL-8 responses of airway epithelial cells to cadmium. Toxicol Sci. 2012;125:418–429. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Järup L., Berglund M., Elinder C.G., Nordberg G., Vahter M. Health effects of cadmium exposure--a review of the literature and a risk estimate. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24(Suppl 1):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo J.I., Kim K.H., Jang H.N., Seo Y.C., Seok K.S., Hong J.H., Jang M. The development of PM emission factor for small incinerators and boilers. Environ Technol. 2002;23:1425–1433. doi: 10.1080/09593332508618447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganguly K., Levanen B., Palmberg L., Akesson A., Linden A. Cadmium in tobacco smokers: a neglected link to lung disease? Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27 doi: 10.1183/16000617.0122-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson-Casey J.L., Gu L., Fiehn O., Carter A.B. Cadmium-mediated lung injury is exacerbated by the persistence of classically activated macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:15754–15766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundblad B.M., Ji J., Levänen B., Midander K., Julander A., Larsson K., Palmberg L., Lindén A. Extracellular cadmium in the bronchoalveolar space of long-term tobacco smokers with and without COPD and its association with inflammation. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2016;11:1005–1013. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S105234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Go Y.M., Orr M., Jones D.P. Actin cytoskeleton redox proteome oxidation by cadmium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L831–L843. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00203.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go Y.M., Orr M., Jones D.P. Increased nuclear thioredoxin-1 potentiates cadmium-induced cytotoxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2013;131:84–94. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yun T.K. Brief introduction of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16(Suppl) doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.S.S3. S3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S.M., Bae B.S., Park H.W., Ahn N.G., Cho B.G., Cho Y.L., Kwak Y.S. Characterization of Korean red ginseng (Panax ginseng meyer): history, preparation method, and chemical composition. J Ginseng Res. 2015;39:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Youn S.H., Lee S.M., Han C.-K., In G., Park C.-K., Hyun S.H. Immune activity of polysaccharide fractions isolated from Korean red ginseng. Molecules. 2020;25:3569. doi: 10.3390/molecules25163569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J.K., Shin K.K., Kim H., Hong Y.H., Choi W., Kwak Y.-S., Han C.-K., Hyun S.H., Cho J.Y. Korean Red Ginseng exerts anti-inflammatory and autophagy-promoting activities in aged mice. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2021;45:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2021.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skoner D.P. Allergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S2–S8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duxbury M.S., Ito H., Zinner M.J., Ashley S.W., Whang E.E. siRNA directed against c-Src enhances pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell gemcitabine chemosensitivity. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:953–959. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin S.J., Jeon S.G., Kim J.I., Jeong Y.O., Kim S., Park Y.H., Lee S.K., Park H.H., Hong S.B., Oh S., Hwang J.Y., Kim H.S., Park H., Nam Y., Lee Y.Y., Kim J.J., Park S.H., Kim J.S., Moon M. Red ginseng attenuates aβ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and aβ-mediated pathology in an animal model of alzheimer's disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20123030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park H.W., In G., Han S.T., Lee M.W., Kim S.Y., Kim K.T., Cho B.G., Han G.H., Chang I.M. Simultaneous determination of 30 ginsenosides in Panax ginseng preparations using ultra performance liquid chromatography. J Ginseng Res. 2013;37:457–467. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S.-J., Choi S., Kim M., Park C., Kim G.-L., Lee S.-O., Kang W., Rhee D.-K. Effect of Korean Red Ginseng extracts on drug-drug interactions. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2018;42:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim C.Y., Moon J.M., Kim B.Y., Lim S.H., Lee G.S., Yu H.S., Cho S.I. Comparative study of Korean White Ginseng and Korean Red Ginseng on efficacies of OVA-induced asthma model in mice. J Ginseng Res. 2015;39:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W., Zhi J., Cui Y., Zhang F., Habyarimana A., Cambier C., Gustin P. Potentiated interaction between ineffective doses of budesonide and formoterol to control the inhaled cadmium-induced up-regulation of metalloproteinases and acute pulmonary inflammation in rats. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Z.H., Lin C., Liu M.M., Zhang J., Tao Z.H., Hu X.C. Src inhibition can synergize with gemcitabine and reverse resistance in triple negative breast cancer cells via the AKT/c-Jun pathway. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerlier D., Thomasset N. Use of MTT colorimetric assay to measure cell activation. J Immunol Methods. 1986;94:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi E., Kim E., Kim J.H., Yoon K., Kim S., Lee J., Cho J.Y. AKT1-targeted proapoptotic activity of compound K in human breast cancer cells. J Ginseng Res. 2019;43:692–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee Y.G., Chain B.M., Cho J.Y. Distinct role of spleen tyrosine kinase in the early phosphorylation of inhibitor of kappaB alpha via activation of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase and Akt pathways. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:811–821. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao Y., Zhu L.H., Guo J., Yuan T., Wang L.Q., Li H., Chen L.X. Farnesyl phenolic enantiomers as natural MTH1 inhibitors from Ganoderma sinense. Oncotarget. 2017;8:95865–95879. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimura K., Nakano Y., Sugizaki T., Shimoda M., Kobayashi N., Kawahara M., Tanaka K.I. Protective effect of polaprezinc on cadmium-induced injury of lung epithelium. Metallomics. 2019;11:1310–1320. doi: 10.1039/c9mt00060g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lag M., Westly S., Lerstad T., Bjørnsrud C., Refsnes M., Schwarze P.E. Cadmium-induced apoptosis of primary epithelial lung cells: involvement of Bax and p53, but not of oxidative stress. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2002;18:29–42. doi: 10.1023/a:1014467112463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Refsnes M., Skuland T., Låg M., Schwarze P.E., Øvrevik J. Differential NF-κB and MAPK activation underlies fluoride- and TPA-mediated CXCL8 (IL-8) induction in lung epithelial cells. J Inflamm Res. 2014;7:169–185. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S69646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hossen M.J., Kim M.Y., Cho J.Y. MAPK/AP-1-Targeted anti-inflammatory activities of Xanthium strumarium. Am J Chin Med. 2016;44:1111–1125. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X16500622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bilia A.R., Bergonzi M.C. The G115 standardized ginseng extract: an example for safety, efficacy, and quality of an herbal medicine. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2020;44:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu L., Zhang A.L., Di Y.M., Shergis J.L., Chen Y., Guo X., Wen Z., Thien F., Worsnop C., Lin L., Xue C.C. Panax ginseng therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical trial protocol and pilot study. Chin Med. 2014;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee J.H., Min D.S., Lee C.W., Song K.H., Kim Y.S., Kim H.P. Ginsenosides from Korean Red Ginseng ameliorate lung inflammatory responses: inhibition of the MAPKs/NF-κB/c-Fos pathways. J Ginseng Res. 2018;42:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song H., Lee Y.Y., Park J., Lee Y. Korean Red Ginseng suppresses bisphenol A-induced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and cellular migration of A549 human lung cancer cell through inhibition of reactive oxygen species. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2021;45:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim S.J., Kwak H.J., Kim D.S., Choi H.M., Sim J.E., Kim S.H., Um J.Y., Hong S.H. Protective mechanism of Korean Red Ginseng in cisplatin-induced ototoxicity through attenuation of nuclear factor-κB and caspase-1 activation. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:315–322. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y., Yang W.S., Yu T., Yi Y.S., Park J.G., Jeong D., Kim J.H., Oh J.S., Yoon K., Kim J.H., Cho J.Y. Novel anti-inflammatory function of NSC95397 by the suppression of multiple kinases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Y., Lee J., Rhee M.H., Yu T., Baek K.S., Sung N.Y., Kim Y., Yoon K., Kim J.H., Kwak Y.S., Hong S., Kim J.H., Cho J.Y. Molecular mechanism of protopanaxadiol saponin fraction-mediated anti-inflammatory actions. J Ginseng Res. 2015;39:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Troutman T.D., Bazan J.F., Pasare C. Toll-like receptors, signaling adapters and regulation of the pro-inflammatory response by PI3K. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:3559–3567. doi: 10.4161/cc.21572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song S.Y., Bae C.H., Choi Y.S., Kim Y.D. Cadmium induces mucin 8 expression via Toll-like receptor 4-mediated extracellular signal related kinase 1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in human airway epithelial cells. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:638–645. doi: 10.1002/alr.21705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding Q., Zhu W., Diao Y., Xu G., Wang L., Qu S., Shi Y. Elucidation of the mechanism of action of ginseng against acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome by a network pharmacology-based strategy. Front Pharmacol. 2021:11. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.611794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.