Abstract

We investigated the posttranscriptional regulation of flgE, a class 2 gene that encodes the hook subunit protein of the flagella. RNase protection assays demonstrated that the flgE gene was transcribed at comparable levels in numerous strains defective in known steps of flagellar assembly. However, Western analyses of these strains demonstrated substantial differences in FlgE protein levels. Although wild-type FlgE levels were observed in strains with deletions of genes encoding components of the switch complex and the flagellum-specific secretion apparatus, no protein was detected in a strain with deletions of the rod, ring, and hook-associated proteins. To determine whether FlgE levels were affected by the stage of hook–basal-body assembly, Western analysis was performed on strains with mutations at individual loci encompassed by the deletion. FlgE protein was undetectable in rod mutants, intermediate in ring mutants, and wild type in hook-associated protein mutants. The lack of negative regulation in switch complex and flagellum-specific secretion apparatus deletion mutants blocked for flagellar construction prior to rod assembly suggests that these structures play a role in the negative regulation of FlgE. Quantitative Western analyses of numerous flagellar mutants indicate that FlgE levels reflect the stage at which flagellar assembly is blocked. These data provide evidence for negative posttranscriptional regulation of FlgE in response to the stage of flagellar assembly.

Transcriptional regulation of operons is well described and provides direct promoter control of the expression of genes involved in integrated structures and metabolic processes. Posttranscriptional control, on the other hand, provides additional layers of regulation to RNA transcripts or their protein products in response to environmental stimuli. A number of mechanisms mediate posttranscriptional control, including mRNA stability, protein stability, protein secretion, transcriptional attenuation, protein or antisense RNA activation-repression, and ribosome frameshifting (11, 19, 33). We have investigated the role of posttranscriptional control during flagellar biosynthesis in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium.

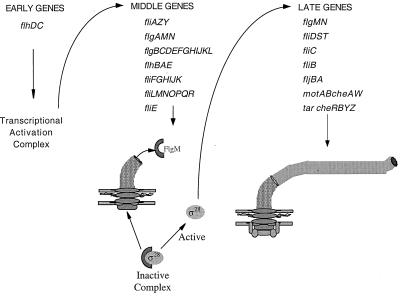

Flagellar biosynthesis in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium involves ordered and hierarchical transcription of flagellar genes that closely parallels organelle assembly. The flagellar regulon includes over 50 genes that can be separated into three transcriptional classes (Fig. 1). Early (class 1) genes encode the transcriptional activators FlhD and FlhC, which are required for expression of all other flagellar genes (4). Middle (class 2) genes encode structural components of the hook-basal body complex (HBB) of the flagellum in addition to two regulatory proteins, the flagellum-specific sigma factor ς28 (36) and the anti-ς28 factor FlgM (37). FlgM inhibits ς28-dependent transcription in strains defective in assembly of the HBB structure (10) by actively dissociating ς28 from RNA polymerase holoenzyme and preventing its reassociation with core RNA polymerase until the HBB structure is fully assembled (6, 37). At this point, FlgM is secreted from the cell via the flagellum-specific secretory apparatus and ς28-dependent late gene (class 3) expression ensues (19, 24). Synthesis of the flagellin filament proteins (FliC and FljB), as well as proteins related to chemotaxis and motility, occurs during this final stage of flagellar assembly. Precursor proteins, including the hook and flagellin subunits, are secreted by a type III secretion system (18, 28). During secretion, most of the flagellar proteins, including the hook and flagellin subunits, are thought to be secreted through a hollow channel in the center of the rod, hook, and growing filament. New subunits are incorporated at the distal end of the elongating structure (9, 20).

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the transcriptional regulatory hierarchy of flagellar proteins. Early (class 1) genes encode FlhD and FlhC, transcriptional activators that are required for expression of all other flagellar genes. Middle (class 2) genes encode structural components of the HBB complex, as well as regulatory proteins, including the sigma factor ς28 and the anti-ς28 factor FlgM. ς28 is required for the expression of all late gene promoters, including those for flagellin and those related to chemotaxis and motility. FlgM binds to and inhibits ς28 until completion of the HBB. FlgM is then secreted from the cell, and ς28-dependent late (class 3) gene expression ensues.

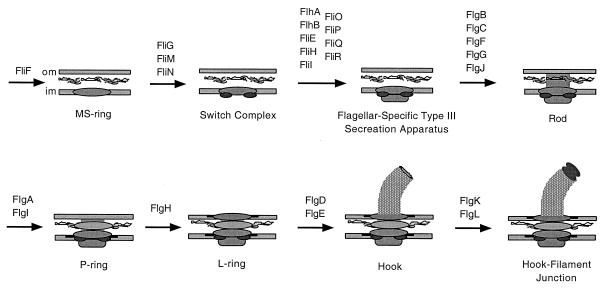

The assembly of the bacterial flagellum of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium can be considered to have three distinct stages: formation of the basal body (BB) (functions as a transmembrane motor), the hook (serves as a flexible linker), and the filament (serves as the propeller) (Fig. 1). The first step of BB assembly is insertion of the MS ring into the inner membrane (23, 43) (Fig. 2). The switch complex and the flagellum-specific type III secretion apparatus are then constructed onto the MS ring (1). The rod component of the BB is composed of the FlgB, FlgC, FlgF (proximal rod), and FlgG (distal rod) proteins (16). These proteins are assembled progressively after completion of the MS ring, the switch complex, and the flagellum-specific secretion apparatus. The flagellum-specific muramidase FlgJ allows the passage of the elongating rod through the peptidoglycan layer (35). The P and L ring subunits (FlgI and FlgH, respectively) are not thought to be secreted by the sec-dependent pathway, and thus their assembly does not require the construction of prior flagellar components (15, 17). After completion of the rings and the rod, the flagellar hook is assembled. Hook length, which normally is about 55 nm, is controlled by secreted nonstructural flagellar protein FliK (34, 38, 41). FliK somehow alters the substrate specificity of the flagellum-specific type III export apparatus. Specifically, the secretion of hook subunits is replaced by secretion of late assembly proteins that include the three hook-associated proteins and the flagellar filament protein subunits (14, 25, 44). The flagellar filament is the last external structural component of the flagellum to be assembled.

FIG. 2.

Schematic of the stepwise progression of HBB assembly.

Complex transcriptional regulatory mechanisms controlling the temporal expression of flagellar proteins have been described. However, a number of observations suggest that posttranscriptional control occurs in the flagellar system. Removal of flagella during the transition from a swarmer to a stalked cell during Caulobacter crescentus development requires degradation of the flagellar “anchor” protein FliF through the action of PleD, a response regulator (2). A Salmonella strain defective for flagellin secretion and derepressed for transcription of late flagellar genes does not accumulate the flagellin protein (FliC) in the cytoplasm, suggesting that FliC undergoes posttranscriptional regulation (H. R. Bonifield and K. T. Hughes, unpublished observations). This is consistent with the finding that FljK and FljL, flagellin proteins in C. crescentus, are posttranscriptionally regulated in response to assembly of prior flagellar components (30). The stability of the FljL protein is decreased in the absence of HBB assembly, suggesting that this protein is regulated posttranslationally (3). On the other hand, regulation of FljK is at the translational level and requires the 5′ untranslated region of the mRNA transcript (3, 31). Mangan et al. (31) have identified a flagellar gene, flbT, that is required for the negative regulation of FljK. In S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, the membrane protein Flk (J. E. Karlinsey and K. T. Hughes, unpublished results) regulates translation of the flagellum-specific anti-sigma factor (FlgM) in response to flagellar ring assembly (22). Here we present evidence that posttranscriptional regulation of flgE, a class 2 gene encoding the hook protein, occurs in response to the stage of flagellar assembly. Specifically, our data demonstrate that once flagellar assembly is started (after construction of the MS ring, switch complex, and flagellum-specific secretion apparatus), the FlgE protein is absent until flagellar hook assembly is initiated. Analysis of flgE transcript levels in mutants in which flagellar assembly is blocked at various stages indicated that the regulation of FlgE expression is not attributable to transcriptional control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The bacterial strains used in this study are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| TH2592 | fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2149 | fla-1191 (ΔflgA-J) fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2150 | fla-2157 (ΔflgG-L) fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2151 | fla-2039 (Δtar-flhD) fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2152 | fla-2018 (ΔflhA-cheA) fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2153 | fla-2050 (ΔfliA-D) fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2154 | fla-2211 (ΔfliE-K) fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2155 | fla-2195 (ΔfliJ-R) fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2156 | flgA2085 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2157 | flgB2164 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2158 | flgC2036 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2159 | flgD1156 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2161 | flgF2083 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2162 | flgG2028 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2163 | flgH2076 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2164 | flgI2002 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2165 | flgJ2076 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2166 | flgK2408 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2167 | flgL2403 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2168 | flhA2007 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2169 | flhB2033 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2170 | flhC2035 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2171 | flhD2040 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2172 | fliA2087 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2173 | fliC1116 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2174 | fliD2380 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2175 | fliE2021 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2176 | fliF2323 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2177 | fliG2250 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2178 | fliH2741 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2179 | fliI2669 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2180 | fliJ1110 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2182 | fliM2190 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2183 | fliN2620 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2184 | fliO2008 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2185 | fliP2041 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2186 | fliQ1180 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| TH2187 | fliR1161 fljB5001::MudJ | 10 |

| SJW204 | ΔflgE1204 | This work |

| TH3434 | ΔflgE1204 fljB5001::MudJ | This work |

| SJW107 | ΔfliK1107 | This work |

| TH3437 | ΔfliK1107 fljB5001::MudJ | This work |

Culture and medium conditions.

Strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani medium with aeration at 37°C as described by Davis et al. (7).

Immunoblot assays for FlgE.

Cells were grown with aeration to a net of 100 Klett units (A600, ∼0.6). A 1.5-ml volume of cells was pelleted and resuspended in 50 μl of 1× sample buffer (27). Protein concentrations of the samples were measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). For each strain, 50 μg of total cellular protein was run on 10% Tricine (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) (39). Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Inc., Keene, N.H.) in CAPS [3-(cyclohexylamino)-1 propanesulfonic acid] buffer (32). Blots were probed with a rabbit anti-FlgE polyclonal antibody. Anti-FlgE serum was generously provided by Shahid Khan (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, N.Y.). Blots were immunostained with an alkaline phosphatase-based reaction in the presence of nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) (19).

Quantitative immunoblot assays.

Western blots were generated as described above, but anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to fluorescein was used to detect the primary antibody (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). Protein levels were measured by scanning the immunoblot with a Storm 840 Imager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.), and quantification of the protein bands was performed using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

RNA isolation and RNase T2 protection assays.

Cells were grown with aeration to a net of 50 Klett units (A600, ∼0.3), and RNA was isolated as described previously (12). RNase T2 protection assays of transcripts from the bacterial chromosome were performed as described by Tsui et al. (42). A radiolabeled RNA probe covering the first 200 nucleotides of the flgBCDEFGHIJKL transcript was synthesized using SP6 polymerase (Promega, Madison, Wis.) as previously described (22). A 50-μg sample of total RNA from each strain was added to the hybridization mixture. Transcript levels were quantified by scanning the gel with a Storm 840 Imager (Molecular Dynamics), and band intensity was determined using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics) and expressed as a percentage of wild-type (WT) band intensity.

RESULTS

FlgE protein levels are negatively regulated in rod assembly mutants.

The flgE gene is transcribed in an operon with other components of the HBB structure of the bacterial flagellum. Electron microscopy studies have determined the order of assembly of HBB components, but the mechanisms allowing this stepwise progression of flagellar assembly are incompletely understood. For example, the rod and hook components of the flagellar BB are cotranscribed yet the rod is assembled prior to the hook by the sequential addition of individual protein subunits. Because the FlgE protein is the most abundant protein within the HBB complex and is assembled last, we hypothesized that FlgE subunits might compete with the secretion of BB subunits during assembly unless some mechanism prevented premature accumulation of the FlgE protein. Thus, expression of the flgE gene or FlgE protein levels would be expected to respond to the stage of BB assembly.

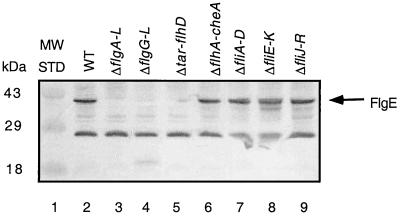

Western blot analysis was performed on crude extracts from WT and BB deletion strains to compare FlgE protein levels. The FlgE protein was present in the WT strain and four of the seven deletion mutants (Fig. 3, lanes 2, 6, 7, 8, and 9). In the other three deletion mutants tested, no FlgE protein was detected (Fig. 3, lanes 3, 4, and 5). Detectable FlgE protein was not expected in two of these deletion mutants. The ΔflgA-J deletion (Fig. 3, lane 3) encompasses the flgE gene itself, and the Δtar-flhD strain encompasses the class 1 transcriptional activators required for flgE transcription (Fig. 3, lane 5). Surprisingly, detectable FlgE protein was also not observed in the flgG-L (encode the rod, ring, and hook-associated proteins) deletion strain. There was no reason a priori to expect that the FlgE protein would be absent in a strain with a deletion of the genes encoding these BB structural proteins.

FIG. 3.

Western analysis of FlgE protein levels in a series of flagellar strains including the WT (lane 2) and the ΔflgA-L (flgA-L deletion which includes the flgE gene, negative control) (lane 3), ΔflgG-L (flgG-L deletion, BB−) (lane 4), Δtar-flhD (tar-flhD deletion, deletion of the flagellar transcriptional regulator flhD) (lane 5), ΔflhA-cheA (flhA-cheA deletion, chemotaxis and flagellum-specific secretion negative) (lane 6), ΔfliA-D (fliA-D deletion, missing ς28-dependent transcription) (lane 7), ΔfliE-K (chemotaxis and flagellum-specific secretion negative) (lane 8), and ΔfliJ-R (flagellum-specific secretion negative) (lane 9) mutants. A 50-μg sample of total cellular lysate of each strain was immunoblotted with anti-FlgE antibody. MW STD, molecular mass standards.

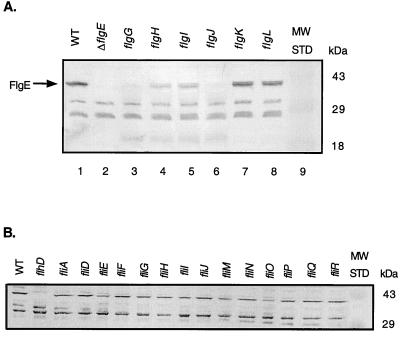

Western blot analysis was performed on strains deficient in individual loci encompassed within the flgG-L deletion to determine whether the loss of one or more of these loci resulted in the reduction of FlgE protein levels observed in the flgG-L deletion strain. The FlgE protein was absent in flgG (distal rod)- and flgJ (peptidoglycanase)-deficient strains (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 6). Intermediate levels were observed in flgH and flgI (L and P ring proteins) mutants (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 and 5), while WT levels were found in flgK and flgL (hook-associated proteins) mutants (Fig. 4A, lanes 7 and 8). Of these loci, only flgG and flgJ are required prior to hook initiation (23). Thus, the FlgE protein was absent until the rod component of the BB was complete and hook assembly was initiated, suggesting that regulation of FlgE is coordinated during the early stages of flagellar assembly.

FIG. 4.

(A) Western blot assay of FlgE protein levels in strains with mutations of the individual genes encompassed in the flgG-L deletion, including flgG (rod mutant), flgH and -I (ring mutants), flgJ (peptidoglycanase mutant), and flgK and -L (hook-filament junction mutants). A 50-μg sample of total cellular lysate of each strain was immunoblotted with anti-FlgE antibody. (B) Western analysis of FlgE levels in a series of flagellum-specific secretion (fliI, -M, -N, -O, -P, -Q and -R) and chemotaxis switch complex (fliG, -M, and -N) mutants. A 50-μg sample of total cellular lysate of each strain was immunoblotted with anti-FlgE antibody. An flhD (transcriptional activator of flagellar genes) mutant was used as a negative control (lane 2). fliA encodes the flagellum-specific sigma factor required for class 3 promoter expression (lane 3). fliD (a class 3 gene) encodes the filament-capping protein and is not required for hook assembly (lane 4). MW STD, molecular mass standards.

Because the switch complex (FliG, FliM, and FliN) and the flagellum-specific secretion apparatus (FlhA, FlhB, FliH, FliI, and FliO-R) are constructed prior to and required for assembly of the rod, we were surprised to find the FlgE protein present in the fliE-K and fliJ-R deletion strains but not in the rod mutant strains (Fig. 3 and 4A). It was possible that a negative regulator of FlgE expression is located in the fli region and removed by both of the fli deletions but is present and active in the rod mutant strains. It was also possible that the switch complex or the flagellum-specific secretion apparatus itself is required for the negative regulation of FlgE protein levels. To distinguish between these two possibilities, FlgE protein levels were determined for strains defective in the individual fli loci encompassed by the fliE-K and fliJ-R deletions. We predicted that if these deletions encompass a negative regulator of FlgE protein levels, WT FlgE protein levels would be observed in all of the strains tested except the one deficient in the negative regulator. We predicted that if the specific component(s) responsible for the regulation only functions in an intact apparatus, or if the entire apparatus is involved in the negative control, then the FlgE protein would be detected in all of the strains with mutations affecting components of the flagellum-specific type III secretion system. The results presented in Fig. 4B show that WT levels of FlgE protein were observed in all of the strains defective in the individual fli loci tested, suggesting that an intact and functional secretion system is necessary for the negative regulation of FlgE expression. These results suggest that the observed decrease in FlgE protein levels occurred in response to the completion of the flagellum-specific secretion apparatus.

FlgE is posttranscriptionally regulated.

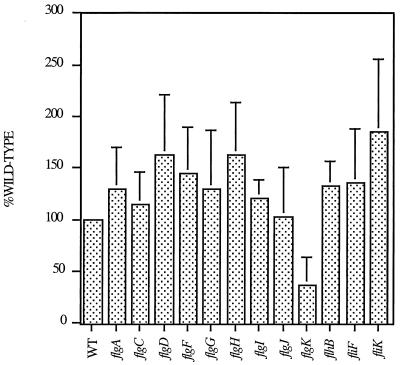

One mechanism that would account for reduced FlgE protein levels in rod assembly mutants is inhibition of flgE transcription in the rod mutant strains. To confirm that our observations were not due to effects of BB mutations on flgE transcription, mRNA levels were directly measured for the flg operon in WT, BB mutant, and flagellum-specific secretion mutant strains using RNase T2 protection assays. Protected transcripts were detected using a radiolabeled RNA probe complementary to the first 200 nucleotides of the flg transcript (22) and quantified. Levels of mRNA were similar in the WT and the BB and flagellum-specific secretion mutant strains (Fig. 5). These data indicate that the observed regulation of FlgE protein levels in response to BB assembly (Fig. 3 and 4A) cannot be accounted for by differences in levels of initiation of flgE transcription and is therefore mediated at the posttranscriptional level.

FIG. 5.

Quantification of flgE transcripts using RNase T2 protection in various flagellar strains, including the WT and the flgA (required for L ring assembly); flgC, -F, and -G (encode BB structural components); flgD (encodes the capping protein for hook assembly); flgI and -H (encode the L and P ring subunits, respectively); flgJ (peptidoglycanase enzyme); flgK (encodes a hook-associated protein); flhB (encodes a component of the type III secretion apparatus); fliF (encodes the MS ring subunit); and fliK (required for hook length regulation) mutants. RNA was purified directly from early exponential phase cells (see Materials and Methods). A radiolabeled RNA probe covering the first 200 nucleotides of the flgBCDEFGHIJKL transcript was synthesized using SP6 polymerase. A 50-μg sample of total RNA from each strain was added to the hybridization mixture. Transcript levels were quantified using a Storm 840 Imager and recorded as PhosphorImager units.

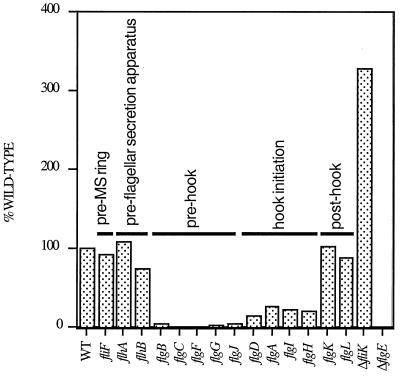

FlgE protein levels are regulated in response to assembly of the BB structure.

The observation that intracellular FlgE protein is present in strains with some HBB genes deleted but not in others suggested that FlgE protein levels are regulated at a specific stage of BB assembly. To better understand how each step of BB assembly affects FlgE protein levels, quantitative Western assays were performed in a wide range of BB mutant backgrounds. These mutants included strains with deletions of fliF (encodes the MS ring subunit; flagellar assembly is not initiated in this mutant); flhA and -B (flagellum-specific secretion components, required for transport of flagellar subunits from the cytoplasm to the tip of the elongating structure, HBB−); flgB, -C, -F and -G (encode structural rod proteins); flgJ (encodes the flagellum-specific muramidase, which allows the elongating rod to pass through the peptidoglycan layer); flgA and -I (required for assembly of the P ring, where the flgI gene encodes the structural component); flgH (encodes the structural component of the L ring); flgD (encodes the hook-capping protein, which provides a scaffold for hook elongation); flgK and -L (encode hook-associated proteins, which provide a linker between the hook and filament); and fliK (encodes a protein required for regulation of flagellar hook length). The results are shown in Fig. 6. In a strain unable to assemble the MS ring (fliF), the hook protein was present at levels comparable to that in the WT. Also, strains without a functional flagellum-specific secretion system (flhA and -B), in which BB assembly is completely blocked, contained WT levels of FlgE protein. Negligible FlgE protein was detected in strains deficient in any gene required for assembly of the rod component of the BB (flgB, -C, -F, -G, and -J). Intermediate levels of FlgE protein were observed in strains blocked for ring or hook assembly (flgA, -I, -H, and -D). WT levels were observed in strains missing the hook-filament junction proteins (encoded by flgK and -L). Because cellular extracts were used for the Western analyses, our immunoblots detected FlgE protein that is incorporated into the flagella, as well as cytoplasmic FlgE protein. We interpret the FlgE protein observed in WT cells to be primarily assembled hook protein. Consistent with this interpretation, a threefold increase in FlgE protein was detected in a strain with a deletion of the hook length regulator FliK. Strains with a fliK mutation are known to produce abnormally long flagellar hook structures and thus would be predicted to have more assembled hook protein subunits (38, 41).

FIG. 6.

Quantitative Western analysis of FlgE levels in a sequential series of isogenic flagellar and type III secretion mutant strains. A 50-μg sample of total cellular lysate of exponentially growing cells was immunoblotted with anti-FlgE serum, and FlgE levels were quantified with a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (see Materials and Methods). The mean of three independent experiments is expressed as a percentage of the WT level.

These data suggest that FlgE expression is posttranscriptionally regulated in response to the stage of BB assembly. This regulation of FlgE occurs after initiation of BB assembly because WT levels of the FlgE protein were present in strains that are unable to begin flagellar assembly (fliF mutant, MS ring negative) (23). The C ring and flagellum-specific secretion apparatus are mounted onto the MS ring once the MS ring is embedded in the inner membrane. Flagellum-specific secretion mutant strains, which cannot assemble the HBB structure, also had WT levels of the FlgE protein. Therefore, FlgE translation or stability is decreased at the stage of rod assembly. Once the flagellum-specific secretion apparatus has been completed, FlgE protein levels are negatively regulated until the rod is assembled and hook assembly has been initiated.

DISCUSSION

The biosynthesis of the bacterial flagellum in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium follows an ordered assembly pathway (1). A transcriptional hierarchy ensures that genes encoding the filament subunit proteins are not expressed until completion of the HBB intermediate structure (26). The work presented here demonstrates that a posttranscriptional control mechanism functions during HBB assembly to facilitate assembly of this intermediate flagellar structure. Specifically, these data provide strong evidence for posttranscriptional control of the flagellar hook subunit protein FlgE. Western analyses and RNase T2 protection assays demonstrated that in a subset of strains with a block in the BB assembly pathway, the FlgE protein was not detected but the gene was transcribed (Fig. 3 and 5). The presence or absence of detectable FlgE protein corresponded to the stage of BB assembly (Fig. 4A). The FlgE protein was detected prior to formation of the MS ring, switch complex, and flagellum-specific type III secretion apparatus (Fig. 4B) but was not detected in strains deficient in any of the structural and enzymatic components required for rod assembly. Intermediate FlgE levels were observed in strains with a block in the next stage of flagellar assembly, i.e., the ring and hook. High FlgE protein levels were observed in strains with blocks in the late stages of flagellar assembly (hook-filament junction proteins) (Fig. 6). These results demonstrate that the posttranscriptional regulation of FlgE parallels BB assembly (Fig. 7). Although flagellum-specific secretion mutants are known to be deficient in HBB assembly, FlgE protein levels were not reduced in flhA and flhB mutants as expected. In fact, Western analyses of FlgE protein levels in a variety of secretion mutants indicate that these strains consistently have WT levels of FlgE. A threefold increase in FlgE protein was observed in a strain with a deletion of the hook length regulator protein FliK. This is consistent with previous observations of an increased amount of hook protein assembled into a structure in these mutants (38, 41).

FIG. 7.

Proposed model of posttranscriptional FlgE control in response to the stage of flagellar assembly. Once assembly has been started (after construction of the MS ring), the FlgE protein is absent until the initiation and subsequent completion of the flagellar hook is possible. Western blots of FlgE protein levels in strains blocked for the diagrammed assembly steps are shown at the bottom.

Posttranscriptional control is known to play an important role in the regulation of bacterial metabolism (45). For example, in many bacteria the expression of amino acid biosynthetic genes is regulated by transcriptional attenuation. Termination of transcription occurs by the formation of a secondary hairpin structure. If cellular levels of a given amino acid are low, the ribosome will stall at a series of “control codons,” which code for the amino acid produced by that operon, located at the 5′ end of the transcript. This ribosome stalling allows the formation of an alternate hairpin structure that precludes the formation of the terminator. Differential mRNA stability following processing of a polycistronic message regulates the production of proteins involved in photosynthesis in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Within the puf operon, genes that encode proteins needed in high amounts form mRNAs with secondary structures that increase the transcript half-life. This allows differential expression of genes within the operon (5). In contrast, secondary mRNA structures in the lamB transcript of Escherichia coli function to block ribosome binding to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, thus inhibiting the translation of lamB (8, 13). LamB is an outer membrane protein which serves a dual function as both a phage receptor and a component of the maltose and maltodextrin transport systems. Historically, investigations of flagellar biosynthesis in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium have focused on describing complex mechanisms of transcriptional regulation. Our laboratory and others are beginning to accumulate evidence that posttranscriptional regulation is also an important factor mediating flagellar gene expression.

In the same way that transcriptional control regulates gene expression between flagellar operons, posttranscriptional control can regulate expression of genes within transcriptional classes. This additional level of regulation may provide increased efficiency to the process of flagellar biosynthesis. Utilization of flagellar proteins is often dependent upon the production and assembly of prior flagellar components (21, 23, 40). For example, the hook (FlgE) cannot be assembled until completion of the BB structure. Posttranscriptional control may prevent the expression of flgE until its product can be added to the elongating flagellar structure. Such a mechanism may play an important role in organizing the process of flagellar biosynthesis. There are approximately 20 flagellar structural genes that are expressed from middle (class 2) promoters in Salmonella, yet the assembly of the flagellar components follows an ordered progression (1, 23). Posttranscriptional regulation may allow nonrandom expression of the middle (class 2) genes, creating an ordered progression of the production, secretion, and assembly of flagellar components. FlgE is the most abundant protein in the HBB complex. If its expression is not regulated, FlgE subunits might compete with the secretion of BB subunits during the assembly process. Elucidation of the general importance of posttranscriptional control in flagellar biosynthesis requires further investigations of other flagellar genes.

Although posttranscriptional regulation of Salmonella flagellar biosynthesis is poorly understood, our results are consistent with previous investigations. Using temperature-sensitive flagellar mutants, Jones and Macnab (21) characterized the assembly progression of the flagellum. By adding [35S]sulfate to cultures before and after shifts to a permissive temperature, the investigators were able to determine whether specific flagellar components (including FlgE) were assembled before or after a block in assembly. Most HBB proteins did not accumulate prior to removal of the assembly block (via a shift to a permissive temperature). While the authors suggested that normal protein degradation was responsible for this phenomenon, our data suggest that at least some of the flagellar proteins are specifically regulated (via protein degradation, translation inhibition, or other mechanisms) in response to the assembly of prior components. It has been proposed that the flagellar operon structure in Salmonella is nonrandom (28). For example, among the class 2 operons, genes encoding proteins with similar functions (e.g., structural components, type III secretion) tend to be clustered together in operons. We note that this organization lends itself to the possibility of ordered translational regulation of these genes, whose products are assembled in a stepwise fashion.

Our observations demonstrate that posttranscriptional control of FlgE production can change in response to the presence of the flagellum-specific type III secretion apparatus. Mutants deficient in any portion of the secretion apparatus exhibit WT levels of FlgE protein, while strains that express a functional secretion apparatus but are deficient in flagellar ring or rod assembly exhibit reduced levels of FlgE. We envision at least three possible means by which FlgE protein levels are reduced in rod and ring mutant strains. First, FlgE protein levels may be controlled by proteolysis. Specifically, FlgE protein may be secreted into the periplasm by a functional secretion apparatus but in rod mutant strains it cannot be incorporated into the structure and is thus subject to proteolysis by periplasmic proteolytic enzymes. Such a mechanism has strong implications for the assembly process. For example, it suggests that there is no selection specificity for secretion of rod and hook subunits but rather selection occurs at the level of incorporation into the elongating flagellar structure. Alternatively, the completed secretion apparatus may activate a protease to degrade any cytoplasmic FlgE until the rod is completed to prevent FlgE subunits from competing with rod subunits for secretion and assembly. Second, differential mRNA processing and/or stability in response to assembly of the secretion apparatus could function to regulate FlgE protein levels. The detection of FlgE protein in rod mutant backgrounds where FlgE is expressed from a truncated mRNA transcript suggests that the flg transcript itself is a target for mediating the negative control of FlgE protein levels prior to hook assembly (data not shown). Finally, the translation of FlgE could occur unregulated until completion of the flagellum-specific secretion apparatus. Upon completion of the type III secretion structure, flgE translation could be inhibited until expression of FlgE can be coupled to secretion and assembly into the elongating structure. The coupling of translation and secretion could provide order in the secretion and incorporation of flagellar rod and hook subunits.

If FlgE regulation is indeed governed by the flagellum-specific secretion apparatus, then it provides a useful phenotype for studying the function of type III secretion components. Subunits of the type III secretion apparatus have previously been studied by identifying proteins required for secretion of distal flagellar proteins yet absent in purified flagellar structures (29). Also, across-species comparisons have been used to identify conserved proteins involved in type III secretion, since this system is so ubiquitous among gram-negative bacteria (18, 28). These approaches have identified many flagellar proteins involved in the type III secretion system. However, there may be unidentified proteins that are involved in type III secretion and the function of the known proteins is poorly understood. This system allows us to identify proteins required for FlgE regulation, with the hypothesis that these are involved in type III secretion. We have already confirmed that all of the flagellum-specific secretion proteins play a role in the negative regulation of FlgE (Fig. 4B and 5), thus verifying previous investigations of the flagellum-specific secretion system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shahid Khan (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, N.Y.) for generously providing the anti-FlgE antibody. We are grateful to Justin Ramsey, Christina Scherer, Steve Lory, and members of the Hughes laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

K.T.H. is a recipient of the American Cancer Society Faculty Research Award. This work was supported by PHS grant GM56141 from the National Institutes of Health awarded to K.T.H. H.R.B. is a recipient of PHS National Research Service Award T32 GM07270 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizawa S-I. Flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.344874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldridge P, Jenal U. Cell cycle-dependent degradation of a flagellar motor component requires a novel-type response regulator. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:379–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson D K, Newton A. Posttranscriptional regulation of Caulobacter flagellin genes by a late flagellum assembly checkpoint. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2281–2288. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2281-2288.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartlett D H, Frantz B B, Matsumura P. Flagellar transcriptional activators FlbB and FlaI: gene sequences and 5′ consensus sequences of operons under FlbB and FlaI control. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1575–1581. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1575-1581.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer C, Buggy J, Mosley C. Control of photosystem genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Trends Genet. 1993;9:56–60. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90188-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chadsey M S, Karlinsey J E, Hughes K T. The flagellar anti-sigma factor FlgM actively dissociates Salmonella typhimurium ς28 RNA polymerase holoenzyme. EMBO J. 1998;17:3123–3136. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis R W, Botstein D, Roth J R. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Smit M H, van Duin J. Control of prokaryotic translational initiation by mRNA secondary structure. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1990;38:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emerson S U, Tokuyasu K, Simon M I. Bacterial flagella: polarity of elongation. Science. 1970;169:190–192. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3941.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillen K L, Hughes K T. Negative regulatory loci coupling flagellin synthesis to flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2301–2310. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2301-2310.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold L. Post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:199–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goluszko P, Moseley S L, Truong L D, Kaul A, Williford J R, Selvarangan R, Nowicki S, Nowicki B. Development of experimental model of chronic pyelonephritis with Escherichia coli O75:K5:H-bearing Dr fimbriae: mutation in the dra region prevented tubulointerstitial nephritis. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:1662–1672. doi: 10.1172/JCI119329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall M N, Gabay J, Debarbouille M, Schwartz M. A role for mRNA secondary structure in the control of translation initiation. Nature. 1982;295:616–618. doi: 10.1038/295616a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirano T, Yamaguchi S, Oosawa K, Aizawa S-I. Roles of FliK and FlhB in determination of flagellar hook length in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5439–5449. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5439-5449.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Homma M, Komeda Y, Iino T, Macnab R M. The flaFIX gene product of Salmonella typhimurium is a flagellar basal body component with a signal peptide for export. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1493–1498. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1493-1498.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Homma M, Kutsukake K, Hasebe M, Iino T, Macnab R M. FlgB, FlgC, FlgF and FlgG. A family of structurally related proteins in the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1990;211:465–477. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90365-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Homma M, Ohnishi K, Iino T, Macnab R M. Identification of flagellar hook and basal body gene products (FlaFV, FlaFVI, FlaFVII, and FlaFVIII) in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3617–3624. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3617-3624.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hueck C. Type III protein secretion systems in the bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:379–433. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.379-433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes K T, Gillen K L, Semon M J, Karlinsey J E. Sensing structural intermediates in bacterial flagellar assembly by export of a negative regulator. Science. 1993;262:1277–1280. doi: 10.1126/science.8235660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iino T. Polarity of flagellar growth in Salmonella. J Gen Microbiol. 1969;56:227–239. doi: 10.1099/00221287-56-2-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones C J, Macnab R M. Flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium: analysis with temperature-sensitive mutants. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1327–1339. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1327-1339.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlinsey J E, Tsui H-C T, Winkler M E, Hughes K T. Flk couples flgM translation to flagellar ring assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5384–5397. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5384-5397.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubori T, Shimamoto N, Yamaguchi S, Namba K, Aizawa S. Morphological pathway of flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:433–446. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90958-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kutsukake K. Excretion of the anti-sigma factor through a flagellar substructure couples flagellar gene expression with flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;243:605–612. doi: 10.1007/BF00279569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutsukake K, Minamino T, Yokoseki T. Isolation and characterization of FliK-independent flagellation mutants from Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7625–7629. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7625-7629.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kutsukake K, Ohya Y, Iino T. Transcriptional analysis of the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:741–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.741-747.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli U K, Favre M. Maturation of the head of bacteriophage T4. I. DNA packaging events. J Mol Biol. 1973;80:575–599. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macnab R M. Flagella and motility. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2 ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macnab R M. Genetics and biogenesis of the bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:131–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangan E K, Bartamian M, Gober J W. A mutation that uncouples flagellum assembly from transcription alters the temporal pattern of flagellar gene expression in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3176–3184. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3176-3184.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mangan E K, Malakooti J, Caballero A, Anderson P, Ely B, Gober J W. FlbT couples flagellum assembly to gene expression in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6160–6170. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6160-6170.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsudaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarthy J E, Gualerzi C. Translational control of prokaryotic gene expression. Trends Genet. 1990;6:78–85. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(90)90098-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minamino T, Gonzalez-Pedrajo B, Yamaguchi K, Aizawa S-I, Macnab R M. FliK, the protein responsible for flagellar hook length control in Salmonella, is exported during hook assembly. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nambu T, Minamino T, Macnab R M, Kutsukake K. Peptidoglycan-hydrolyzing activity of the FlgJ protein, essential for flagellar rod formation in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1555–1561. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1555-1561.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohnishi K, Kutsukake K, Suzuki H, Iino T. Gene fliA encodes an alternative sigma factor specific for flagellar operons in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:139–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00261713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohnishi K, Kutsukake K, Suzuki H, Iino T. A novel transcriptional regulatory mechanism in the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium: an anti sigma factor inhibits the activity of the flagellum-specific sigma factor, ςF. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3149–3157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterson-Delafield J, Martinez R J, Stocker B A, Yamaguchi S. A new fla gene in Salmonella typhimurium—flaR—and its mutant phenotype—superhooks. Arch Mikrobiol. 1973;90:107–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00414513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schägger H, Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki T, Iino T, Horiguchi T, Yamaguchi S. Incomplete flagellar structures in nonflagellate mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1978;133:904–915. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.2.904-915.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki T, Iino T. Role of the flaR gene in flagellar hook formation in Salmonella spp. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:973–979. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.3.973-979.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsui H C T, Pease A J, Koehler T M, Winkler M E. Detection and quantitation of RNA transcribed from bacterial chromosomes. Methods Mol Genet. 1994;3:179–204. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ueno T, Oosawa K, Aizawa S. M ring, S ring and proximal rod of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium are composed of subunits of a single protein, FliF. J Mol Biol. 1992;227:672–677. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams A W, Yamaguchi S, Togashi F, Aizawa S I, Kawagishi I, Macnab R M. Mutations in fliK and flhB affecting flagellar hook and filament assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2960–2970. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2960-2970.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanofsky C. Attenuation in the control of expression of bacterial operons. Nature. 1981;289:751–758. doi: 10.1038/289751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]