Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an increasingly serious public health problem in the world, but the effective therapeutic approach is quite limited at present. Cellular senescence is characterized by the irreversible cell cycle arrest, senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) and senescent cell anti-apoptotic pathways (SCAPs). Renal senescence shares many similarities with CKD, including etiology, mechanism, pathological change, phenotype and outcome, however, it is difficult to judge whether renal senescence is a trigger or a consequence of CKD, since there is a complex correlation between them. A variety of cellular signaling mechanisms are involved in their interactive association, which provides new potential targets for the intervention of CKD, and then extends the researches on senotherapy. Our review summarizes the common features of renal senescence and CKD, the interaction between them, the strategies of senotherapy, and the open questions for future research.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, cellular senescence, interaction, mechanism, therapy

1 Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a group of chronic diseases caused by inflammation, metabolic disorders, toxins and other various factors (Boor et al., 2010). It afflicts more than 13% of the world’s population (Hill et al., 2016). It is generally characterized by progressive glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis and renal failure, as well as non-renal complications (Dai et al., 2019). What could be the root cause(s) of the persistence of renal injury, multi-organ involvement and the final renal failure in CKD? Among multiple explanations, the effect of cellular senescence on CKD has been gaining attention (Xu et al., 2020).

Cellular senescence is defined as the permanent cessation of cell proliferation (Kuilman et al., 2010) and is used to describe ageing on cellular level. It is characterized by the stable cell cycle arrest, apoptosis inhibition, sustained high metabolic rate and a pro-inflammatory state called senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (Di Micco et al., 2021). Actually, kidney is one of the most significantly affacted organs during the process of natural ageing (Long et al., 2005). Renal ageing and senescence lead to renal pathophysiological changes and systemic geriatric phenotypes, which are similar to those of CKD. It should be noted that renal senescence can also occur in sick children and may reduce their renal regeneration potential (Melk et al., 2009).

In view of the similarities between CKD and renal senescence, it is speculated that they are closely related (Kubben and Misteli, 2017). In fact, senescence is strongly associated not only with the development of CKD, but also with the progression of CKD, and vice versa (Schroth et al., 2020). Though effective treatments to halt or reverse CKD are extremely limited, regulating renal senescence is expected to provide a new target for its intervention.

In present review, the evidences for the interactive association of renal senescence and CKD, potential mechanisms that might explain this association, therapeutic approaches targeting senescence for the intervention of CKD, and the prospects for the future are discussed.

2 Basic concepts of cellular senescence

Traditionally, cellular senescence has been divided into two types, namely Hayflick-type replicative senescence, characterized by the telomere attrition (Hayflick and Moorhead, 1961), and stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS), caused by various stimuli (von Zglinicki, 2002; Sedelnikova et al., 2004; Wiley et al., 2016; Petrova et al., 2016). A variety of markers have been used to identify cellular senescence, among which the senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity at pH 6.0, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors such as p16ink4a (hereafter referred as p16) and p21CIP1 (hereafter referred as p21), and SASPs are the most common ones (Hernandez-Segura et al., 2018). The p53/p21 and p16/retinoblastoma (RB) pathways are the most critical signaling pathways that are related to cellular senescence (Calcinotto et al., 2019) (Figure 1). Another important factor leading to the expansion and spread of cellular senescence is SASPs, which are a series of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors secreted by senescent cells (Valentijn et al., 2018), such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-8, transforming growth factors-β (TGF-β), plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). SASPs enable the primary senescent cells to direct adjacent or distant nonsenescent cells to experience secondary senescence in autocrine, paracrine, and juxtacrine manners (Admasu et al., 2021). Another function of the SASPs is to activate immune surveillance and recruit immune cells to eliminate senescent cells (Faget et al., 2019). However, the accumulation of senescent cells often gradually exceeds the clearance capacity of the immune cells, contributing to the development of senescence.

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms of cellular senescence. Senescence inducers, such as oxidative stress, DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction and epigenetic stress, can activate the ataxia telangiectasia mutated/ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATM/ATR) signaling and other multiple pathways, resulting in p53 phosphorylation and increased p21 transcription, and/or p16 over-experession. Activation of p21 and p16 inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) or CDK4/CDK6 and prevents retinoblastoma (RB) phosphorylation, leading to G1/S cell cycle arrest. Additionally, activated ATM/ATR signaling can also induce G2/M cell cycle arrest via checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1) and Chk2. Wnt/β-catenin promotes senescence by stimulating p53 and p16, while klotho and sirtuins 1 (SIRT1) inhibit senescence by blocking these pathways. Cellular senescence initially leads to elevated senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) and senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP) release. However, if senescence persisists, it may evolve to chronic senescence and secondary senescence, and contributes to various degradations. DDR, DNA damage response; SIPS, stress-induced premature senescence.

3 The association between renal senescence and CKD

As mentioned above, renal ageing and senescence share numerous similarities with CKD in renal and systemic manifestations. Besides, the similarities are also reflected in their pathogenic mechanisms, such as the secretion of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and loss of renoprotective factors (O’Sullivan et al., 2017). It is reported that SASP and CKD-associated secretory phenotype appear to have a lot in common (Wang et al., 2017). Renal fibrosis is regarded as the main determinant of the gradual loss of renal function and the prognosis of CKD (Higgins et al., 2018). The cytokine mediated signaling pathways, such as the TGF-β/Smad pathway and the Wnt pathway, which play important roles in renal fibrosis (Isaka 2018; Luo et al., 2018), are also involved in renal senescence. In addition, the immune deficiency in CKD is analogous to immunosenescence (Sato and Yanagita, 2019).

3.1 Evidence for renal senescence in CKD

The characteristics of cellular senescence are presented in all parts of renal parenchyma in CKD patients and animal models (Dai et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). P53 is over-expressed in the lymphocytes of CKD patients, and the mesenchymal stem cells from CKD rats are prematurely senescent (Klinkhammer et al., 2014). Because the renal functional reserve is gradually impaired, renal senescence undoubtedly increases the susceptibility to CKD (Nitta et al., 2013). Indeed, the average prevalence of CKD in the elderly is significantly higher than that in the young (Prakash and O’Hare, 2009). The fact that elevated p16 level and SA-β-gal activity often precede the renal changes in different stages of CKD and CKD-related renal diseases (Li and Wang, 2018), p21 level is significantly up-regulated in human transplanted kidney undergoing AKI-to-CKD transition (Cippà et al., 2018), the pathological changes of renal fibrosis, inflammation and microvascular rarefaction in the elderly mice are more significant than those in the young control group in the ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) model of CKD (Clements et al., 2013), and p21 knockout ameliorates progression to CKD in mouse models (Megyesi et al., 1999), suggesting that renal senescence is involved in the pathogenesis and progression of CKD.

3.2 Evidence for CKD in renal senescence

Compared with the general population, the renal ageing and senescence process is greatly accelerated and advanced in CKD patients (Dai et al., 2019). Besides, a high prevalence of senescent cells has been noticed in renal biopsies of young patients with diverse CKD (Halloran and Melk, 2001). Moreover, the shortening of telomeres and the increase of SA-β-gal levels in collecting tubules of CKD cats are more significant than those in general cats, whether young or aged (Quimby et al., 2013).

4 Potential mechanisms for association of renal senescence and CKD

Various animal models have been used to study the association between renal senescence and CKD or CKD-related renal diseases (Table 1). As mentioned above, renal senescence may be both the cause and the consequence of CKD. Acute senescence is a protective response to various renal insults, which plays a role in promoting immune clearance and tissue repair (van Deursen.., 2014). However, if senescent cells are not cleared in time, they will gradually accumulate, and may induce chronic senescence. As reported by various studies, senescent cell accumulation contributes to SASPs secretion and signaling, abnormal renal repair, and renal fibrosis (Braun et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012; Cippà et al., 2018), further leading to CKD and its systemic complications (Schroth et al., 2020). In turn, various pathological products of CKD stimulate the kidney to remain in a state of chronic inflammation, oxidative stress and metabolic abnormality, which promotes the induction and accumulation of chronic senescent cells.

TABLE 1.

Animal model studies on the relationship between cellular senecence and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| Model | Intervention | Effect of intervention | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|

| renal IRI Lee et al., (2012) | p16ink4a/p19ARF double KO | improved epithelial repair, renal fibrosis and inflammation | Reduced senescence has a renoprotective effect in AKI |

| renal Tx Braun et al., (2012) | p16ink4a KO | less atrophy and fibrosis after Tx | Inhibiting senescence have therapeutic benefit in kidney transplantation |

| DN Wolf et al., (2005) | p27kip1 KO | reduced glomerular hypertrophy and tubule-interstitial lesion | Inhibiting senescence by deletion of p27Kip1, an inhibitor of CDKs, attenuates the functional and morphologic features of DN. |

| DN Al-Douahji et al., (1999) | p21cip1 KO | mitigated proteinuria and glomerular expansion | Inhibiting senescence ameliorates glomerular hypertrophy in DN, which is protective of renal function |

| CKD Chang et al., (2016) | upregulate klotho | reduced vascular calcification | Inhibiting senescence by upregulating α-klotho attenuates vascular calcification in CKD. |

| CKD Hum et al., (2017) | stable delivery of AAV expressing klotho | reduced hyperphosphatemia | Inhibiting senescence by sustained klotho treatment reduces hyperphosphatemia in CKD. |

| CKD Hu et al., (2011) | transgenic overexpressing klotho | enhanced renal function and less calcification | Inhibiting senescence by overexpressing klotho ameliorates vascular calcification and preserves renal function in CKD. |

| chronic GN Haruna et al., (2007) | klotho transgene | reduced proteinuria and improved renal function | Inhibiting senescence by genetic manipulation of klotho gene ameliorates progressive renal injury in CKD. |

| post-AKI CKD Shi et al., (2016) | recombinant αklotho administration | accelerated renal recovery and reduced renal fibrosis | Inhibiting senescence by αklotho overexpression mitigates renal fibrosis and retards AKI progression to CKD. |

| UUO Gong et al., (2021) | knockdown of BRG-1 | reduced renal fibrosis | Reduced senescence attenuates renal fibrosis in CKD. |

| UUO Adis et al., (2013) | rhEPO | mitigated tubular epithelial cell regeneration and renal fibrosis | Inhibiting senescence by erythropoietin preserves tubular epithelial cell regeneration and ameliorates renal fibrosis in CKD. |

| telomerase deficient Westhoff et al., (2010) | renal IRI | higher expression of p21, and reduced cellular regeneration | IRI leads to increased senescence |

Multiple animal models have been used to study the association between CKD and renal senescence. Since CKD may be caused by various renal diseases, especially acute kidney injury (AKI), glomerulonephritis (GN) and diabetes nephropathy (DN), those CKD-related renal diseases are also included in the research on the association between CKD and renal senescence. This table summarizes several of these studies, and describes the models and the interventions that are used in them, as well as the effects of the interventions. AAV, adeno-associated virus; BRG-1, brahma-related gene-1; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; IRI, ischemia-reperfusion injury; KO, knock-out; rhEPO, recombinant huma erythropoietin; Tx, transplant; UUO, unilateral ureteric obstruction.

4.1 Renal senescence promoting CKD

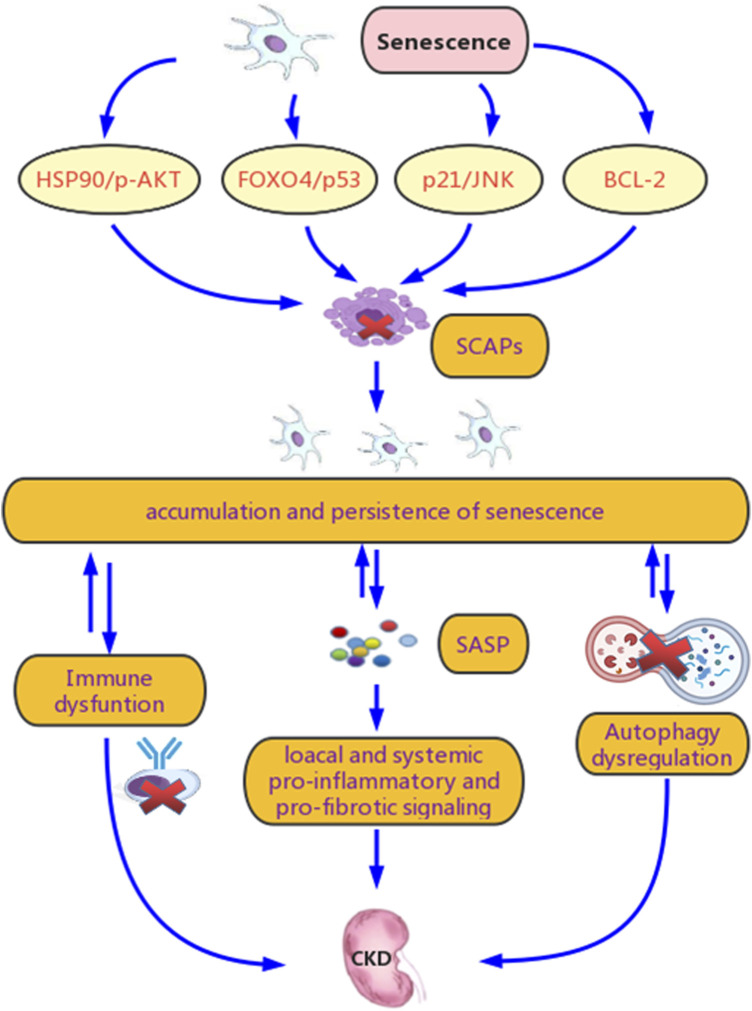

The persistence of chronic senescent cells plays a critical role in the correlation between renal senescence and CKD (Figure 2). The interactions between cell cycle regulators and inhibitors, changes in the balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic factors, and metabolic abnormalities may explain this persistence and its promoting effect on CKD.

FIGURE 2.

Potential mechanisms for senescence promoting chronic kidney disease (CKD). Renal senscence and CKD are tightly connected. Chronic stimulation of various stressors in CKD leads to the continuous and excessive induction of chronic senescent cells and relaease of senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which contributes to their accumulation and persistence. Another crucial reason for their persistence is senescent cell anti-apoptotic pathways (SCAPs), which prevents senescent cells from clearance mainly though the B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2), Forkhead box O4 (FOXO4)/p53, p21/JNK and HSP90/p-AKT pathways. Meanwhile, this persistence promotes SASP secretion and spread, induces abnormal renal repair, and exacerbate renal fibrosis, culminating in CKD progression and its systemic complications. Dysregulation of autophagy and immune system are involved in both the persistence of senescence and the progression of CKD.

4.1.1 Senescent cell anti-apoptotic pathways

5SCAPs refer to mechanisms that contribute to the prolonged survival of senescent cells (Wang et al., 2021). Activation of the BCL-2 family, ephrin ligand B1 (EFNB1), EFNB3, Forkhead box O-4 (FOXO-4), HSP90/p-AKT, and p21/JNK plays an important role in SCAPs (Wang et al., 2021). BCL-2 inhibits autophagy by interacting with autophagy protein Beclin1 and suppressing the formation of autophagosome (Yosef et al., 2016; Goligorsky, 2020). FOXO-4 is a p53 sequester in the nucleus, which can restrict p53-mediated apoptosis (Baar et al., 2017). The activation of p21 prevents senescent cells from apoptosis by limiting JNK signaling and caspase (Yosef et al., 2017). Stabilized p-AKT by HSP90 also contributes to the prolonged survival of senescent cells (Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg et al., 2017). In fact, agents targeting the SCAPs can inhibit renal senescence and decline of renal function in chronological and transgenic ageing mice (Baar et al., 2017), indicating a relationship between SCAPs and CKD.

4.1.2 Autophagy dysregulation

Autophagy is a highly conserved process of cellular degradation and recycling. Thus, impaired autophagy will lead to the persistence and accumulation of senescent cells. The role of autophagy in cellular senescence is related to αklotho (Shi et al., 2016), telomerase (Harris and Cheng, 2016) and adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/rapamycin (mTOR) pathway (Goligorsky, 2020). Autophagy dysregulation is also involved in promoting CKD (Lenoir et al., 2016). It has been shown that knockout of rubicon, a negative regulator of autophagy (Nakamura et al., 2019), and the autophagic flux induced by calorie restriction (CR) (Schmitt and Melk, 2017) can slow down the process of renal tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis.

4.1.3 SASPs

Continuous stimulation of SASPs is crucial in promoting CKD, because it contributes to the enhancement and propagation of senescent phenotypes, induces abnormal renal repair, and causes a decline in renal function. Besides, factors related to chronic release of SASPs are also known as pro-fibrotic factors (Goligorsky, 2020), such as TGF-β and Wnt. Therefore, SASPs are able to exacerbate renal fibrosis, and further lead to CKD deterioration (Goligorsky, 2020). In addition to their local effects on the kidney, SASPs also induce systemic transmission of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic signaling, resulting in systemic phenotypes of CKD (Goligorsky, 2020).

4.1.4 Immune system alterations

Abnormal activation of the innate immune system in CKD patients leads to increased pro-inflammatory cytokines (Sato and Yanagita, 2019) and senescence of renal tubular cells (Jin et al., 2017). The adaptive immune response of CKD patients is also affected, which is characterized by the increase of CD4+CD28− cells (Lisowska et al., 2012), the decrease of regulatory T (Treg) cells (Lisowska et al., 2012) and immature B cells (Kim et al., 2012), a shift toward the pro-inflammatory Th1 differentiation (Litjens et al., 2006), and the decline of CD4/CD8 T cell ratio (Yoon et al., 2006). The accumulation of senescent cells is not only due to immune dysfunction, but also related to immune evasion (Pereira et al., 2019). In addition, infiltration of pro-inflammatory B cells and T cells conduce to a pro-fibrotic milieu, and induce renal fibrosis, leading to CKD progression (Lee et al., 2017).

4.2 CKD promoting the renal senescence

The potential mechanisms for CKD promoting renal senescence are showed in Figure 3, and the details are as follows.

FIGURE 3.

Potential mechanisms for chronic kidney disease (CKD) promoting senescence. CKD contributes to senescence mainly by Multiple pathological products of CKD leads to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic abnormality in the kidney, which contributes to senescence. Besides, telomere attrition, klotho defect, sirtuins (SIRTs) deficiency, autophagy inhibition, and immune dysfunction are also important causes for increased senescence. Various signaling pathways are involved in the promotion of senescence in CKD, mainly include factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), Wnt/β-catenin, NF-κB, and mTOR. AGEs, advanced glycation end products; RAGE, AGE-receptor for advanced glycation end products; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

4.2.1 Telomere attrition

Stresses induced by multiple kidney injuries in CKD accelerate telomere attrition, subsequently leading to increased replicative senescence (Wills and Schnellmann, 2011). Studies have shown that the telomere lengths of T cells in patients with end stage renal disease are shorter than those in healthy group (Hirashio et al., 2014), the telomerase activities of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) increase with the progression of CKD (Kidir et al., 2017), and Poly (A)-specific ribonuclease (PARN) mutation, a key cause of telomere abnormality-related diseases, is prevalent in CKD patients (Lata et al., 2018), which indicating that CKD is closely related to telomere dysfunction.

4.2.2 Oxidative stress and inflammatory burden

Systemic oxidative stress and inflammatory burden, caused by over-activation of renin-angiotension-aldosterone system (RAAS), reduction of antioxidant factors, hyperphosphatemia, or other various factors, is prevalent in CKD, which has been considered to be one of the key mechanisms leading to renal senescence (Qaisar et al., 2018). It is reported that the burden of inflammation in CKD children seems to be much higher than that in general children (Lambert et al., 2004). Increased metabolic rate and ATP consumption trigger mitochondrial dysfunction, consequently leading to reactive oxygen species (ROS) over-production (Tamaki et al., 2014), which is the basis of increased oxidative stress, even in the early stage of CKD. The nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) is a key regulator of antioxidant enzymes. Senescence markers, such as p16, p21 and SASPs, are increased in NRF2-deficient mice (Fulop et al., 2018). In the PBMC of CKD, the decreased expression of NRF2 is accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction (Liu et al., 2019) and up-regulation of pro-inflammatory factors, such as NF-κB (Stockler-Pinto et al., 2018). On the contrary, the NRF2 agonist bardoxolone inhibits senescence in the CKD mouse model (Nagasu et al., 2019).

4.2.3 Uremic toxins

Uremic toxins, such as advanced glycation end products (AGEs), are accumulated in CKD due to increased generation and decreased clearance (Stinghen et al., 2016). Children with CKD also shows high circulating levels of AGEs (Misselwitz et al., 2002). AGE/AGE-receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) axis activates the NF-κB pathway (Sanajou et al., 2018), induces endoplasmatic reticulum stress (Liu et al., 2014), inhibits autophagy (Shi et al., 2019), and promotes p16 (Liu et al., 2015) and p21 (Liu et al., 2014) expression, resulting in increased renal senescence. On the contrary, reduced senescence is observed in rodents over-expressing the AGE-detoxifying enzyme Glo-1 (Hirakawa et al., 2017).

4.2.4 Klotho defect

Klotho, an anti-senescence single-pass transmembrane protein, is primarily expressed in the proximal and distal tubules of kidney (Zou et al., 2018). Klotho regulates cellular senescence mainly by attenuating p53/p21 and Wnt/β-catenin pathways (Kuro-o., 2019). In addition, klotho is involved in regulating the activity of many other pathways, such as TGF-β, NRF2, FGF23, and IGF-1 (Sopjani et al., 2015), thereby inhibiting cellular senescence. Studies have shown that klotho begins to decline in very early stages of CKD (Wang et al., 2021), and the TGF-β signaling plays a crucial role in down-regulating klotho in CKD (Zhou et al., 2013). Klotho defect leads to the increased cellular senescence and secretion of SASPs (Castilho et al., 2009), aggravates renal fibrosis and promotes a variety of systemic phenotypes.

4.2.5 Sirtuins deficiency

Sirtuins (SIRTs) are a group of NAD+-dependent deacetylases (Morigi et al., 2018), which has a deep impact on a variety of cytokines and signaling pathways related to cellular senescence, such as FOXO, p53 (Li et al., 2019), NF-κB, NRF2/ARE pathway (Zhuang et al., 2021), PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/parkin axis (Liu et al., 2020), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (Sun et al., 2021), and hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-2α (Li et al., 2021). SIRT1 is widely expressed in normal renal tubular cells and podocytes, but decreases with renal diseases or ageing (Lim et al., 2012). Decreased SIRT1 activity leads to reduced production of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ coactivator-1a (PGC-1a) and autophagy (Lim et al., 2012), loss of resistance to ROS, suppression of FOXO, inhibition of AMPK, and activation of p53, resulting in cellular senescence and renal injuries (Goligorsky, 2020). Podocyte-specific reduction of SIRT1 promotes glomerulosclerosis and podocyte loss in mice (Chuang et al., 2017). Besides, capillary rarefaction is also related to the lack of SIRT1 in renal endothelial cells (Kida et al., 2016).

4.2.6 Abnormality of immune system

For children with CKD, they show accelerated immune maturation and impaired immune function, and are forced into a state of premature immune senescence (George et al., 2017). Their CD4/CD8 ratio seems to be inverted, and CD57, a marker of senescence, is significantly increased, indicating the existence of immune senescence (George et al., 2017). Under the continuous stimulation of chronic inflammation in CKD, the replicative ability of T cells is impaired, leading to replicative senescence (Hayflick, 1965).

5 Targeting renal senescence in therapy of CKD

At present, the treatments of CKD are mainly focused on the etiology, symptoms and complications. When CKD progresses to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), renal replacement therapy, such as hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, is needed. However, the mortality of CKD patients is still high, and their life quality is low. Since senescence plays an important role in CKD, it could be assumed as a new target for CKD treatment (Tan et al., 2022). The approach of targeting senescence is known as senotherapy, which mainly includes senolytics, senomorphics, and rejuvenating agents (Goligorsky, 2020). The common agents are listed in Table 2. In recent years, numerous studies have confirmed their great potentials in ameliorating CKD and its complications (Knoppert et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021).

TABLE 2.

Therapeutic approaches against cellular senescence.

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; DHA, dehydroascorbic acid; EGCG, epigallocatechin gallate; FOXO4-DRI, Forkhead box O-4-D-Retro-Inverso; PPAR-γ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ.

5.1 Nonpharmacologic approaches

CR mitigates senescence-associated renal changes by activating SIRT1 and AMPK, blocking mTOR and NF-κB signaling pathways, and inhibiting the activity of endothelin-1 (ET-1) (Wang et al., 2021), thereby promoting autophagy and reducing oxidative stress (Ning et al., 2013).

5.2 Senolytics

Senolytics eliminate senescent cells by promoting the pro-apoptotic pathways, inhibiting the SCAPs or activating the immune system (Sturmlechner et al., 2017). Preclinical studies have shown the exciting potential of multiple senolytics in reversing renal senescence (Knoppert et al., 2019). Dasatinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that disturbs EFNB-dependent suppression of apoptosis, and quercetin is a natural flavonol that restrains PI3K and serpins (Wang et al., 2021). These two agents are often used in combination, and referred as “D + Q” (Wang et al., 2021). They are reported to alleviate senescence-related dysfunction in cell cultures and animal models (Xu et al., 2018). They can also significantly decrease the levels of p16, p21, SA-β-gal and SASPs in the adipose and skin tissues of patients with diabetic kidney diseases (Hickson et al., 2019). As the first generation senolytic in mice, ABT-263 inhibits the BCL-2 family, resulting in extensive apoptosis of senescent cells (Chang et al., 2016). FOXO4-DRI induces selective apoptosis of senescent cells by competitively inhibiting the FOXO4-p53 interaction, thus protecting renal function in aged mice (Zhang et al., 2020).

5.3 Senomorphics

Senomorphics are a group of SASP regulators, which can alleviate renal senescence in CKD (Schroth et al., 2020) by modulating a variety of pathways, such as MAPK, mTOR, NF-κB and NRF2 pathways (Iwasa et al., 2003). Metformin, an AMPK activator, has been proved to inhibit the induction of p16, p21, and SASPs, improve the function of mitochondrial complex I, activate autophagy (Piskovatska et al., 2019), reduce the production of ROS in cultured podocytes and prevent diabetes-induced renal hypertrophy (Lee et al., 2007; Piwkowska et al., 2010). A recent study showed that metformin exerts its anti-senescence effect by targeting senescent mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) in CKD (Kim et al., 2021). Since the side effects of metformin are minimal and are likely to be reversible, it is expected to be applicated in healthy individuals to block senescence-related renal changes (Barzilai et al., 2016). At present, the mTOR inhibitors mainly include rapamycin and its analog rapalog. They have attracted high attention in the treatment of renal diseases for their positive effect on renal senescence and fibrosis (Shavlakadze et al., 2018). However, their side effects are also significant, such as immunosuppression, infection and metabolic disorders (Fang et al., 2020). Therefore, they are not the best choice for healthy people to prevent renal senescence. Administration of pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate, an NF-κB inhibitor, alleviates renal interstitial fibrosis in rats (Okabe et al., 2013). Besides, inhibiting the activation of NF-κB at 24 h after AKI improves recovery of renal function and attenuates renal fibrosis (Johnson et al., 2017). The NRF2 agonist bardoxolone showed promising efficacy in CKD patients, but it was later discontinued because of the high rate of heart failure in patients randomly treated with it (de Zeeuw et al., 2013). Additionally, the potential oncogenic risks of NRF2 activators also need attention (Vega et al., 2018).

5.4 Rejuvenating agents

As an example of rejuvenating agent, resveratrol can improve senescence-related renal injury by activating SIRT1, reducing oxidative stress and inhibiting the pro-inflammatory SASPs (Wang et al., 2017). Besides, a variety of SIRT1 activators have been used to prevent and treat senesence-related renal deficiency (Han et al., 2021), such as SRT1460 (Zhao and Yu., 2021), SRT 1720 (Ren et al., 2017), SRT2183 (He et al., 2010), D-Pinitol (Koh et al., 2018), Isoliquiritigenin (Huang et al., 2020), and Rutin (Khajevand-Khazaei et al., 2018). Klotho expression can be stimulated by reactivation of endogenous klotho or supplement of exogenous klotho, so as to improve renal fibrosis and reduce senescence (Zou et al., 2018). Demethylation of the klotho gene promoter, klotho gene delivery and inhibition of histone deacetylase are potential strategies for the up-regulation of klotho (Zou et al., 2018). Several drugs have been reported to increase endogenous klotho (Zou et al., 2018), such as intermedin, and further alleviate senescence-related renal changes. In addition, direct administration of exogenous soluble klotho is also effective in improving the level of circulating klotho and preventing CKD.

5.5 Immunomodulation

Immunomodulatory therapy for senescence may be achieved by enhancing the tolerance to acute injury, inhibiting the pro-inflammatory state of senescent immune cells, and promoting the clearance of senescent cells. Peripheral tolerance is mainly controlled by dendritic cells (DCs) by inducing Tregs and T cell anergy. In a IRI model, the treatment of adenosine 2A receptor agonist in vitro can induce tolerogenic DCs, which further inhibit the activation of natural killer T (NKT) cells, thereby protecting the kidney (Li et al., 2012). Suppressing p38/MAPK in senescent CD8+ T cells improves their telomerase activity and mitochondrial function (Henson et al., 2014). Immunotherapies may also be used to eliminate senescent cells, such as reinfusion of ex vivo derived DCs, vaccines, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells (Qudrat et al., 2017). By blocking the interaction between the non-classical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule human leukocyte antigen-E (HLA-E) and the inhibitory receptor NKG2A expressed by NK and highly differentiated CD8+ T cells, the immune clearance of senescent cells can be improved (Pereira et al., 2019).

6 Future prospects

Renal senescence and CKD share common characteristics and mechanisms, and there is a complex interactive relationship between them (Figure 4). Renal senescence is a promising target for therapeutic intervention of CKD, as preclinical data have shown the efficacy of senotherapies (Tan et al., 2022). In the future, more effective senotherapies and their judicious implementation are expected to fight against the progression of CKD or even reverse CKD, however, several challenges remained.

FIGURE 4.

The interactive association between renal senescence and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Various studies have demonstrated that renal senescence and CKD are closely related, both in vitro and in vivo. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, loss of reno-protective factors, secretion of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors, activation of associated signaling pathways, autophagy inhibition, and immune deficiency, are considered to be involved in their complex interaction.

6.1 A deeper understanding of the pleiotropic effects of senotherapy

How to avoid the influence of senotherapy on the beneficial biological function of senescence and its potential toxicity to non-senescent cells and the whole organism? How to optimize dosing and limit adverse effects? These are remained major challenges. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct extensive researches on the pleiotropic effects of senotherapy.

6.2 Combing senotherapy with immunomodulation

On the one hand, senotherapy may enhance the dysregulated immune function in CKD, but immune-mediated CKD may deteriorate due to excessive immune activation (Schroth et al., 2020). On the other hand, the down-regulation of SASP caused by senotherapy will not only reduce cellular senescence, but also lead to the failure of recognizing SASP-inhibited senescent cells by immune cells and the reduction of SASP mediators involved in immune cell recruitment (Schroth et al., 2020), which will hinder immune-mediated clearance and further lead to the excessive accumulation of senescent cells. Therefore, it may be necessary to combine immunomodulation with senotherapy to achieve the triple therapy of specifically eliminating senescent cells, blocking their SASPs signaling, and promoting their immune targeting for CKD intervention (Schroth et al., 2020).

6.3 Heterogeneity identification of cellular senescence

Whether SASPs and SCAPs have specificity in different types of senescent cells? How to distinguish the short-term and long-term effects of senescent cells? Is there any difference between the response of primary senescence and secondary senescence to the current senotherapy? All these issues need further study. Another important point is the need for cell type-specific or tissue-specific identification of senescent cell markers. Single cell RNA sequencing can characterize and identify senescence on a single cell basis, which may help us to understand the dynamics and heterogeneity of senescent cells in affected organs. Targeted drug delivery to the kidney may further enhance the therapeutic effects of senotherapy on renal diseases and reduce its potential off-target effects.

6.4 Determination of the burden of senescent cells

The burden of senescent cells in the kidney may be a useful index for predicting renal prognosis (Liu et al., 2012). The problem is how to determine it. None of the current senescent markers are specific and unique. Besides, not all of the cells with these markers show senescent pathologies (Kirkland and Tchkonia, 2020), and different senescent subtypes are displayed when cells respond to the same stimulus (Chen et al., 2020). Limited by the detection methods, especially in vivo, the actual burden of senescent cells in CKD is still unclear. Additionally, whether the increase of senescent cells in renal biopsy can better predict CKD progression than existing markers requires prospective studies. It seems urgent to identify unique markers and convenient methods to detect and quantify senescence.

Author contributions

J-HM and J-LZ conceived the review and wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the collection of the related research articles. J-LZ prepared the original figures and tables figures. J-HM critically revised the texts. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Natural Foundation of China (U20A20351), Key Research and Development Plan of Zhejiang Province (2021C03079), the Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang, Zhejiang province (2020KY891). These funding sustained the design of the study, and the collection and analysis of data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Adis T., Supranee K., Sookkasem K. (2013). Dual inhibiting senescence and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by erythropoietin preserve tubular epithelial cell regeneration and ameliorate renal fibrosis in unilateral ureteral obstruction. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 308130. 10.1155/2013/308130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Admasu T. D., Rae M., Stolzing A. (2021). Dissecting primary and secondary senescence to enable new senotherapeutic strategies. Ageing Res. Rev. 70, 101412. 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Douahji M., Brugarolas J., Brown P. A., Stehman-Breen C. O., Alpers C. E., Shankland S. J. (1999). The cyclin kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 is required for glomerular hypertrophy in experimental diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 56, 1691–1699. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00728.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisimov V. N., Egorov M. V., Krasilshchikova M. S., Lyamzaev K. G., Manskikh V. N., Moshkin M. P., et al. (2011). Effects of the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant SkQ1 on lifespan of rodents. Aging 3, 1110–1119. 10.18632/aging.100404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baar M. P., Brandt R. M. C., Putavet D. A., Klein J. D. D., Derks K. W. J., Bourgeois B. R. M., et al. (2017). Targeted apoptosis of senescent cells restores tissue homeostasis in response to chemotoxicity and aging. Cell 169 (1), 132–147.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai N., Crandall J. P., Kritchevsky S. B., Espeland M. A. (2016). Metformin as a tool to target aging. Cell Metab. 23, 1060–1065. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boor P., Ostendorf T., Floege J. (2010). Renal fibrosis: Novel insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 6 (11), 643–656. 10.1038/nrneph.2010.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun H., Schmidt B. M. W., Raiss M., Baisantry A., Mircea-Constantin D., Wang S., et al. (2012). Cellular senescence limits regenerative capacity and allograft survival. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 1467–1473. 10.1681/ASN.2011100967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcinotto A., Kohli J., Zagato E., Pellegrini L., Demaria M., Alimonti A. (2019). Cellular senescence: Aging, cancer, and injury. Physiol. Rev. 99 (2), 1047–1078. 10.1152/physrev.00020.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilho R., Squarize C., Chodosh L., Williams B., Gutkind S. (2009). mTOR mediates Wnt-induced epidermal stem cell exhaustion and aging. Cell Stem Cell 5, 279–289. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. R., Guo J., Wang Y., Hou Y. L., Lu W. W., Zhang J. S., et al. (2016). Intermedin1-53 attenuates vascular calcification in rats with chronic kidney disease by upregulation of alpha-Klotho. Kidney Int. 89 (3), 586–600. 10.1016/j.kint.2015.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J., Wang Y., Shao L., Laberge R. M., Demaria M., Campisi J., et al. (2016). Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat. Med. 22, 78–83. 10.1038/nm.4010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Wang X., Wei G., Huang Y., Shi Y., Li D., et al. (2020). Single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals six subpopulations reflecting distinct cellular fates in senescent mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Front. Genet. 11, 867. 10.3389/fgene.2020.00867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang P. Y., Cai W., Li X., Fang L., Xu J., Yacoub R., et al. (2017). Reduction in podocyte SIRT1 accelerates kidney injury in aging mice. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 313, F621–F628. 10.1152/ajprenal.00255.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cippà P. E., Sun B., Liu J., Chen L., Naesens M., McMahon A. P. (2018). Transcriptional trajectories of human kidney injury progression. JCI Insight 3 (22), e123151. 10.1172/jci.insight.123151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements M. E., Chaber C. J., Ledbetter S. R., Zuk A. (2013). Increased cellular senescence and vascular rarefaction exacerbate the progression of kidney fibrosis in aged mice following transient ischemic injury. PLoS One 8 (8), e70464. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L., Qureshi A. R., Witasp A., Lindholm B., Stenvinkel P. (2019). Early vascular ageing and cellular senescence in chronic kidney disease. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 17, 721–729. 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zeeuw D., Akizawa T., Audhya P., Bakris G. L., Chin M., Christ-Schmidt H., et al. (2013). Bardoxolone methyl in type 2 diabetes and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 2492–2503. 10.1056/NEJMoa1306033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Micco R., Krizhanovsky V., Baker D., d'Adda di Fagagna F. (2021). Cellular senescence in ageing: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 75–95. 10.1038/s41580-020-00314-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faget D. V., Ren Q., Stewart S. A. (2019). Unmasking senescence: Context- dependent effects of SASP in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 19, 439–453. 10.1038/s41568-019-0156-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Gong A. Y., Haller S. T., Dworkin L. D., Liu Z., Gong R. (2020). The ageing kidney: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Ageing Res. Rev. 63, 101151. 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman K., Martínez F., Cifuentes M., Fernandez M., Bertinat R., Torres P., et al. (2020). Dehydroascorbic acid, the oxidized form of vitamin c, improves renal histology and function in old mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 235, 9773–9784. 10.1002/jcp.29791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H., Ling Y. Y., Zhao J., McGowan S. J., Zhu Y., Brooks R. W., et al. (2017). Identification of HSP90 inhibitors as a novel class of senolytics. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 422. 10.1038/s41467-017-00314-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulop G. A., Kiss T., Tarantini S., Balasubramanian P., Yabluchanskiy A., Farkas E., et al. (2018). Nrf2 deficiency in aged mice exacerbates cellular senescence promoting cerebrovascular inflammation. GeroScience 40, 513–521. 10.1007/s11357-018-0047-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George R. P., Mehta A. K., Perez S. D., Winterberg P., Cheeseman J., Johnson B., et al. (2017). Premature T cell senescence in pediatric CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28 (1), 359–367. 10.1681/ASN.2016010053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goligorsky M. S. (2020). Chronic kidney disease: A vicarious relation to premature cell senescence. Am. J. Pathol. 190 (6), 1164–1171. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W., Luo C., Peng F., Xiao J., Zeng Y., Yin B., et al. (2021). Brahma-related gene-1 promotes tubular senescence and renal fibrosis through Wnt/β-catenin/autophagy axis. Clin. Sci. 135 (15), 1873–1895. 10.1042/CS20210447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griveau A., Wiel C., Ziegler D. V., Bergo M. O., Bernard D. (2020). The JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib delays premature aging phenotypes. Aging Cell 19, e13122. 10.1111/acel.13122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halloran P. F., Melk A. (2001). Renal senescence, cellular senescence, and their relevance to nephrology and transplantation. Adv. Nephrol. Necker Hosp. 31, 273–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Ding C., Sang X., Peng M., Yang Q., Ning Y., et al. (2021). Targeting sirtuin1 to treat aging-related tissue fibrosis: From prevention to therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 229, 107983. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. C., Cheng H. (2016). Telomerase, autophagy and acute kidney injury. Nephron 134 (3), 145–148. 10.1159/000446665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruna Y., Kashihara N., Satoh M., Tomita N., Namikoshi T., Sasaki T., et al. (2007). Amelioration of progressive renal injury by genetic manipulation of Klotho gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 (7), 2331–2336. 10.1073/pnas.0611079104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L., Moorhead P. S. (1961). The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 25, 585–621. 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L. (1965). The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 37, 614–636. 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T., Xiong J., Nie L., Yu Y., Guan X., Xu X., et al. (2016). Resveratrol inhibits renal interstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy by regulating AMPK/NOX4/ROS pathway. J. Mol. Med. 94, 1359–1371. 10.1007/s00109-016-1451-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W., Wang Y., Zhang M. Z., You L., Davis L. S., Fan H., et al. (2010). Sirt1 activation protects the mouse renal medulla from oxidative injury. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 1056–1068. 10.1172/JCI41563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson S. M., Lanna A., Riddel N. E., Franzese O., Macaulay R., Griffiths S. J., et al. (2014). p38 signaling inhibits mTORC1-independent autophagy in senescent human CD8⁺ T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 4004–4016. 10.1172/JCI75051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Segura A., Nehme J., Demaria M. (2018). Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 436–453. 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickson L. T. J., Langhi Prata L. G. P., Bobart S. A., Evans T. K., Giorgadze N., Hashmi S. K., et al. (2019). Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: Preliminary report from a clinical trial of dasatinib plus quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine 47, 446–456. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S. P., Tang Y., Higgins C. E., Mian B., Zhang W., Czekay R. P., et al. (2018). TGF-β1/p53 signaling in renal fibrogenesis. Cell. Signal. 43, 1–10. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill N., Fatoba S., Oke J., Hirst J. A., O'Callaghan C. A., Lasserson D. S., et al. (2016). Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 11, e0158765. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa Y., Jao T. M., Inagi R. (2017). Pathophysiology and therapeutics of premature ageing in chronic kidney disease, with a focus on glycative stress. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 44, 70–77. 10.1111/1440-1681.12777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashio S., Nakashima A., Doi S., Anno K., Aoki E., Shimamoto A., et al. (2014). Telomeric g-tail length and hospitalization for cardiovascular events in hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 9 (12), 2117–2122. 10.2215/CJN.10010913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M. C., Shi M., Zhang J., Quinones H., Griffith C., Kuro-o M., et al. (2011). Klotho deficiency causes vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22 (1), 124–136. 10.1681/ASN.2009121311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Shi Y., Chen H., Le R., Gong X., Xu K., et al. (2020). Isoliquiritigenin prevents hyperglycemia-induced renal injuries by inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress via SIRT1-dependent mechanism. Cell Death Dis. 11, 1040. 10.1038/s41419-020-03260-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hum J. M., O'Bryan L. M., Tatiparthi A. K., Cass T. A., Clinkenbeard E. L., Cramer M. S., et al. (2017). Chronic hyperphosphatemia and vascular calcification are reduced by stable delivery of soluble klotho. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28 (4), 1162–1174. 10.1681/ASN.2015111266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaka Y. (2018). Targeting TGF-beta signaling in kidney fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (9), 2532–32. 10.3390/ijms19092532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa H., Han J., Ishikawa F. (2003). Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 defines the common senescence signalling pathway. Genes Cells. 8, 131–144. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C., Hömme M., Melk A. (2011). Is cellular senescence important in pediatric kidney disease? Pediatr. Nephrol. 26 (12), 2121–2131. 10.1007/s00467-010-1740-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H., Zhang Y., Ding Q., Wang S. S., Rastogi P., Dai D. F., et al. (2017). Epithelial innate immunity mediates tubular cell senescence after kidney injury. JCI Insight 4, e125490. 10.1172/jci.insight.125490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johmura Y., Yamanaka T., Omori S., Wang T. W., Sugiura Y., Matsumoto M., et al. (2021). Senolysis by glutaminolysis inhibition ameliorates various age-associated disorders. Science 371, 265–270. 10.1126/science.abb5916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson F. L., Patel N. S. A., Purvis G. S. D., Chiazza F., Chen J., Sordi R., et al. (2017). Inhibition of IκB kinase at 24 hours after acute kidney injury improves recovery of renal function and attenuates fibrosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e005092. 10.1161/JAHA.116.005092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khajevand-Khazaei M. R., Mohseni-Moghaddam P., Hosseini M., Gholami L., Baluchnejadmojarad T., Roghani M. (2018). Rutin, a quercetin glycoside, alleviates acute endotoxemic kidney injury in C57BL/6 mice via suppression of inflammation and up-regulation of antioxidants and SIRT1. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 833, 307–313. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida Y., Zullo J. A., Goligorsky M. S. (2016). Endothelial sirtuin 1 inactivation enhances capillary rarefaction and fibrosis following kidney injury through Notch activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 478 (3), 1074–1079. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidir V., Aynali A., Altuntas A., Inal S., Aridogan B., Sezer M. T. (2017). Telomerase activity in patients with stage 2-5D chronic kidney disease. Nefrologia 37 (6), 592–597. 10.1016/j.nefro.2017.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Yu M. R., Lee H., Kwon S. H., Jeon J. S., Han D. C., et al. (2021). Metformin inhibits chronic kidney disease-induced DNA damage and senescence of mesenchymal stem cells. Aging Cell 20, e13317. 10.1111/acel.13317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. U., Yoon K. J., Park S., Lee J. C., Moon H. Y., Moon M. H. (2020). Exercise-induced recovery of plasma lipids perturbed by ageing with nanoflow UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 412, 8003–8014. 10.1007/s00216-020-02933-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. W., Chung B. H., Jeon E. J., Kim B. M., Choi B. S., Park C. W., et al. (2012). B cell-associated immune profiles in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Exp. Mol. Med. 44, 465–472. 10.3858/emm.2012.44.8.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland J. L., Tchkonia T. (2020). Senolytic drugs: From discovery to translation. J. Intern. Med. 288, 518–536. 10.1111/joim.13141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkhammer B. M., Kramann R., Mallau M., Makowska A., van Roeyen C. R., Rong S., et al. (2014). Mesenchymal stem cells from rats with chronic kidney disease exhibit premature senescence and loss of regenerative potential. PLoS One 9, e92115. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppert S., Valentijn F., Nguyen T., Goldschmeding R., Falke L. (2019). Cellular senescence and the kidney: Potential therapeutic targets and tools. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 770. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh E. S., Kim S., Kim M., Hong Y. A., Shin S. J., Park C. W., et al. (2018). D-Pinitol alleviates cyclosporine A-induced renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis via activating Sirt1 and Nrf2 antioxidant pathways. Int. J. Mol. Med. 41, 1826–1834. 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubben N., Misteli T. (2017). Shared molecular and cellular mechanisms of premature ageing and ageing-associated diseases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 595–609. 10.1038/nrm.2017.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuilman T., Michaloglou C., Mooi W. J., Peeper D. S. (2010). The essence of senescence. Genes Dev. 24, 2463–2479. 10.1101/gad.1971610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Sharma A., Kumari A., Gulati A., Padwad Y. (2019). Epigallocatechin gallate suppresses premature senescence of preadipocytes by inhibition of pi3k/akt/mtor pathway and induces senescent cell death by regulation of bax/bcl-2 pathway. Biogerontology 20, 171–189. 10.1007/s10522-018-9785-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuro-o M. (2019). The klotho proteins in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 27–44. 10.1038/s41581-018-0078-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M., Delvin E. E., Paradis G., O’Loughlin J., Hanley J. A., Levy E. (2004). C-reactive protein and features of the metabolic syndrome in a population-based sample of children and adolescents. Clin. Chem. 50, 1762–1768. 10.1373/clinchem.2004.036418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lata S., Marasa M., Li Y., Fasel D. A., Groopman E., Jobanputra V., et al. (2018). Whole-exome sequencing in adults with chronic kidney disease: A pilot study. Ann. Intern. Med. 168 (2), 100–109. 10.7326/M17-1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. H., Wolstein J. M., Pudasaini B., Plotkin M. (2012). INK4a deletion results in improved kidney regeneration and decreased capillary rarefaction after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 302, F183–F191. 10.1152/ajprenal.00407.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. J., Feliers D., Mariappan M. M., Sataranatarajan K., Mahimainathan L., Musi N., et al. (2007). A role for AMP-activated protein kinase in diabetes-induced renal hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 292, F617–F627. 10.1152/ajprenal.00278.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. A., Noel S., Sadasivam M., Hamad A. R. A., Rab H. (2017). Role of immune cells in acute kidney injury and repair. Physiol. Behav. 176, 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir O., Tharaux P. L., Huber T. B. (2016). Autophagy in kidney disease and aging: Lessons from rodent models. Kidney Int. 90 (5), 950–964. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Xie N., Li Y., Liu C., Hou F., Wang J. (2019). N-acetylcysteine ameliorates cisplatin-induced renal senescence and renal interstitial fibrosis through sirtuin 1 activation and p53 deacetylation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 130, 512–527. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Huang L., Ye H., Song S. P., Bajwa A., Lee S. J., et al. (2012). Dendritic cells tolerized with adenosine A₂AR agonist attenuate acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 3931–3942. 10.1172/JCI63170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P. P., Liu Y., Qin X. G., Chen K., Wang R., Yuan L., et al. (2021). SIRT1 attenuates renal fibrosis by repressing HIF-2α. Cell Death Discov. 7, 59. 10.1038/s41420-021-00443-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Wang Z. (2018). Aging kidney and aging-related disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1086, 169–187. 10.1007/978-981-13-1117-8_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H., Park H., Kim H. P. (2015). Effects of flavonoids on senescence-associated secretory phenotype formation from bleomycin-induced senescence in BJ fibroblasts. Biochem. Pharmacol. 96 (4), 337–348. 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J. H., Kim E. N., Kim M. Y., Chung S., Shin S. J., Kim H. W., et al. (2012). Age-associated molecular changes in the kidney in aged mice. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2012, 171383. 10.1155/2012/171383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisowska K. A., Dębska-Ślizień A., Jasiulewicz A., Heleniak Z., Bryl E., Witkowski J. M. (2012). Hemodialysis affects phenotype and proliferation of CD4-positive T lymphocytes. J. Clin. Immunol. 32, 189–200. 10.1007/s10875-011-9603-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litjens N. H. R., Van Druningen C. J., Betjes M. G. H. (2006). Progressive loss of renal function is associated with activation and depletion of naive T lymphocytes. Clin. Immunol. 118, 83–91. 10.1016/j.clim.2005.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Gidlund E., Witasp A., Qureshi A. R., Soderberg M., Thorell A., et al. (2019). Reduced skeletal muscle expression of mitochondrial derived peptides humanin and MOTS-C and Nrf2 in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 317 (5), F1122–F1131. 10.1152/ajprenal.00202.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Huang K., Cai G. Y., Chen X. M., Yang J. R., Lin L. R., et al. (2014). Receptor for advanced glycation end-products promotes premature senescence of proximal tubular epithelial cells via activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent p21 signaling. Cell. Signal. 26, 110–121. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Yang J. R., Chen X. M., Cai G. Y., Lin L. R., He Y. N. (2015). Impact of ER stress-regulated ATF4/p16 signaling on the premature senescence of renal tubular epithelial cells in diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 308, C621–C630. 10.1152/ajpcell.00096.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Yang J. R., He Y. N., Cai G. Y., Zhang J. G., Lin L. R., et al. (2012). Accelerated senescence of renal tubular epithelial cells is associated with disease progression of patients with immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy. Transl. Res. 159 (6), 454–463. 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Yang Q., Zhang X., Qin R., Shan W., Zhang H., et al. (2020). Quercetin alleviates kidney fibrosis by reducing renal tubular epithelial cell senescence through the SIRT1/PINK1/mitophagy axis. Life Sci. 257, 118116. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long D. A., Mu W., Price K. L., Johnson R. J. (2005). Blood vessels and the aging kidney. Nephron. Exp. Nephrol. 101, e95–99. 10.1159/000087146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C., Zhou S., Zhou Z., Liu Y., Yang L., Liu J., et al. (2018). Wnt9a promotes renal fibrosis by accelerating cellular senescence in tubular epithelial cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 29 (4), 1238–1256. 10.1681/ASN.2017050574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megyesi J., Price P. M., Tamayo E., Safirstein R. L. (1999). The lack of a functional p21 (WAF1/CIP1) gene ameliorates progression to chronic renal failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 (19), 10830–10835. 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melk A., Schmidt B. M., Braun H., Vongwiwatana A., Urmson J., Zhu L. F., et al. (2009). Effects of donor age and cell senescence on kidney allograft survival. Am. J. Transpl. 9, 114–123. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02500.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misselwitz J., Franke S., Kauf E., John U., Stein G. (2002). Advanced glycation end products in children with chronic renal failure and type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Nephrol. 17, 316–321. 10.1007/s00467-001-0815-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morigi M., Perico L., Benigni A. (2018). Sirtuins in renal health and disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 29 (7), 1799–1809. 10.1681/ASN.2017111218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasu H., Sogawa Y., Kidokoro K., Itano S., Yamamoto T., Satoh M., et al. (2019). Bardoxolone methyl analog attenuates proteinuria-induced tubular damage by modulating mitochondrial function. FASEB J. 33, 12253–12263. 10.1096/fj.201900217R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S., Oba M., Suzuki M., Takahashi A., Yamamuro T., Fujiwara M., et al. (2019). Suppression of autophagic activity by Rubicon is a signature of aging. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 847. 10.1038/s41467-019-08729-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Y. C., Cai G. Y., Zhuo L., Gao J. J., Dong D., Cui S., et al. (2013). Short-term calorie restriction protects against renal senescence of aged rats by increasing autophagic activity and reducing oxidative damage. Mech. Ageing Dev. 134 (11-12), 570–579. 10.1016/j.mad.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta K., Okada K., Yanai M., Takahashi S. (2013). Aging and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 38, 109–120. 10.1159/000355760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe C., Borges R. L., de Almeida D. C., Fanelli C., Barlette G. P., Machado F. G., et al. (2013). NF-κB activation mediates crystal translocation and interstitial inflammation in adenine overload nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 305 (2), 155–163. 10.1152/ajprenal.00491.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan E., Hughes J., Ferenbach D. (2017). Renal aging: Causes and consequences. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 407–420. 10.1681/asn.2015121308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira B. I., Devine O. P., Vukmanovic-Stejic M., Chambers E. S., Subramanian P., Patel N., et al. (2019). Senescent cells evade immune clearance via HLA-E-mediated NK and CD8+ T cell inhibition. Nat. Commun. 10, 2387. 10.1038/s41467-019-10335-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova N. V., Velichko A. K., Razin S. V., Kantidze O. L. (2016). Small molecule compounds that induce cellular senescence. Aging Cell 15, 999–1017. 10.1111/acel.12518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskovatska V., Stefanyshyn N., Storey K. B., Vaiserman A. M., Lushchak O. (2019). Metformin as a geroprotector: Experimental and clinical evidence. Biogerontology 20, 33–48. 10.1007/s10522-018-9773-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwkowska A., Rogacka D., Jankowski M., Dominiczak M. H., Stepiński J. K., Angielski S. (2010). Metformin induces suppression of NAD(P)H oxidase activity in podocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 393, 268–273. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S., O’Hare A. M. (2009). Interaction of aging and chronic kidney disease. Semin. Nephrol. 29, 497–503. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qaisar R., Bhaskaran S., Premkumar P., Ranjit R., Natarajan K. S., Ahn B., et al. (2018). Oxidative stress-induced dysregulation of excitation-contraction coupling contributes to muscle weakness. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 9 (5), 1003–1017. 10.1002/jcsm.12339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qudrat A., Wong J., Truong K. (2017). Engineering mammalian cells to seek senescence-associated secretory phenotypes. J. Cell Sci. 130, 3116–3123. 10.1242/jcs.206979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quimby J. M., Maranon D. G., Battaglia C. L. R., McLeland S. M., Brock W. T., Bailey S. M. (2013). Feline chronic kidney disease is associated with shortened telomeres and increased cellular senescence. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 305, F295–F303. 10.1152/ajprenal.00527.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y., Du C., Shi Y., Wei J., Wu H., Cui H. (2017). The Sirt1 activator, SRT1720, attenuates renal fibrosis by inhibiting CTGF and oxidative stress. Int. J. Mol. Med. 39 (5), 1317–1324. 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador L., Singaravelu G., Harley C. B., Flom P., Suram A., Raffaele J. M. (2016). A natural product telomerase activator lengthens telomeres in humans: A randomized, double blind, and placebo controlled study. Rejuvenation Res. 19 (6), 478–484. 10.1089/rej.2015.1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaraweera L., Adomako A., Rodriguez-Gabin A., McDaid H. M. (2017). A novel indication for panobinostat as a senolytic drug in NSCLC and HNSCC. Sci. Rep. 7, 1900. 10.1038/s41598-017-01964-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanajou D., Ghorbani Haghjo A., Argani H., Aslani S. (2018). Age-Rage axis blockade in diabetic nephropathy: Current status and future directions. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 833, 158–164. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Yanagita M. (2019). Immunology of the ageing kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 625–640. 10.1038/s41581-019-0185-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt R., Melk A. (2017). Molecular mechanisms of renal aging. Kidney Int. 92 (3), 569–579. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroth J., Thiemermann C., Henson S. M. (2020). Senescence and the aging immune system as major drivers of chronic kidney disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9 (8), 564461. 10.3389/fcell.2020.564461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedelnikova O. A., Horikawa I., Zimonjic D. B., Popescu N. C., Bonner W. M., Barrett J. C. (2004). Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 168–170. 10.1038/ncb1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavlakadze T., Zhu J., Wang S., Zhou W., Morin B., Egerman M. A., et al. (2018). Short-term low-dose mTORC1 inhibition in aged rats counter-regulates age-related gene changes and blocks age-related kidney pathology. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 73 (7), 845–852. 10.1093/gerona/glx249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M., Flores B., Gillings N., Bian A., Cho H. J., Yan S., et al. (2016). αKlotho mitigates progression of AKI to CKD through activation of autophagy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27 (8), 2331–2345. 10.1681/ASN.2015060613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M., Yang S., Zhu X., Sun D., Sun D., Jiang X., et al. (2019). The RAGE/STAT5/autophagy axis regulates senescence in mesangial cells. Cell. Signal. 62, 109334. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopjani M., Rinnerthaler M., Kruja J., Dermaku-Sopjani M. (2015). Intracellular signaling of the aging suppressor protein Klotho. Curr. Mol. Med. 15, 27–37. 10.2174/1566524015666150114111258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinghen A. E. M., Massy Z. A., Vlassara H., Striker G. E., Boullier A. (2016). Uremic toxicity of advanced glycation end products in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 354–370. 10.1681/ASN.2014101047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockler-Pinto M. B., Soulage C. O., Borges N. A., Cardozo L. F. M. F., Dolenga C. J., Nakao L. S., et al. (2018). From bench to the hemodialysis clinic: Protein-bound uremic toxins modulate NF-κB/Nrf2 expression. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 50, 347–354. 10.1007/s11255-017-1748-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmlechner I., Durik M., Sieben C. J., Baker D. J., van Deursen J. M. (2017). Cellular senescence in renal ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 13 (2), 77–89. 10.1038/nrneph.2016.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. J., Xiong S. P., Cao X., Cao L., Zhu M. Y., Wu Z. Y., et al. (2021). Polysulfide-mediated sulfhydration of SIRT1 prevents diabetic nephropathy by suppressing phosphorylation and acetylation of p65 NF-kappa B and STAT3. Redox Biol. 38, 101813. 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki M., Miyashita K., Wakino S., Mitsuishi M., Hayashi K., Itoh H. (2014). Chronic kidney disease reduces muscle mitochondria and exercise endurance and its exacerbation by dietary protein through inactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase. Kidney Int. 85 (6), 1330–1339. 10.1038/ki.2013.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H., Xu J., Liu Y. (2022). Ageing, cellular senescence and chronic kidney disease: Experimental evidence. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 31 (3), 235–243. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentijn F., Falke L., Nguyen T., Goldschmeding R. (2018). Cellular senescence in the aging and diseased kidney. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 12, 69–82. 10.1007/s12079-017-0434-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deursen J. M. (2014). The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature 509, 439–446. 10.1038/nature13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega M. R., de la Chapman E., Zhang D. D. (2018). NRF2 and the hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Cell 34, 21–43. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zglinicki T. (2002). Oxidative stress shortens telomeres. Trends biochem. Sci. 27, 339–344. 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02110-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. Y., Wang S. Y., Liu J. Q., Song Y. H., Li P., Sun X. F., et al. (2019). Methionine restriction delays senescence and suppresses the senescence-associated secretory phenotype in the kidney through endogenous hydrogen sulfide. Cell cycle 18 (14), 1573–1587. 10.1080/15384101.2019.1618124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. J., Cai G. Y., Chen X. M. (2017). Cellular senescence, senescence associated secretory phenotype, and chronic kidney disease. Oncotarget 8, 64520–64533. 10.18632/oncotarget.17327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. H., Ao Q. G., Cheng Q. L. (2021). Caloric restriction inhibits renal artery ageing by reducing endothelin-1 expression. Ann. Transl. Med. 9, 979. 10.21037/atm-21-2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang Y., Yang M., Ma X. (2021). Implication of cellular senescence in the progression of chronic kidney disease and the treatment potencies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 135, 111191. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westhoff J. H., Schildhorn C., Jacobi C., Homme M., Hartner A., Braun H., et al. (2010). Telomere shortening reduces regenerative capacity after acute kidney injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21, 327–336. 10.1681/ASN.2009010072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley C. D., Velarde M. C., Lecot P., Liu S., Sarnoski E. A., Freund A., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial dysfunction induces senescence with a distinct secretory phenotype. Cell Metab. 23, 303–314. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills L. P., Schnellmann R. G. (2011). Telomeres and telomerase in renal health. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22 (1), 39–41. 10.1681/ASN.2010060662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf G., Schanze A., Stahl R. A., Shankland S. J., Amann K. (2005). p27(Kip1) Knockout mice are protected from diabetic nephropathy: Evidence for p27(Kip1) haplotype insufficiency. Kidney Int. 68, 1583–1589. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Xu X., Zhang F., Wang M., Xu Y., Tang D., et al. (2017). The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant mitoq ameliorated tubular injury mediated by mitophagy in diabetic kidney disease via Nrf2/PINK1. Redox Biol. 11, 297–311. 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Zhou L., Liu Y. (2020). Cellular senescence in kidney fibrosis: Pathologic significance and therapeutic strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 601325. 10.3389/fphar.2020.601325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Ma X., Verma N., Perie L., Pendse J., Shamloo S., et al. (2020). PPARγ agonists delay age-associated metabolic disease and extend longevity. Aging Cell 19, e13267. 10.1111/acel.13267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Pirtskhalava T., Farr J. N., Weigand B. M., Palmer A. K., Weivoda M. M., et al. (2018). Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med. 24, 1246–1256. 10.1038/s41591-018-0092-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J. W., Gollapudi S., Pahl M. V., Vaziri N. D. (2006). Naive and central memory T-cell lymphopenia in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 70, 371–376. 10.1038/sj.ki.5001550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef R., Pilpel N., Papismadov N., Gal H., Ovadya Y., Vadai E., et al. (2017). p21 maintains senescent cell viability under persistent DNA damage response by restraining JNK and caspase signaling. EMBO J. 36 (15), 2280–2295. 10.15252/embj.201695553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef R., Pilpel N., Tokarsky-Amiel R., Biran A., Ovadya Y., Cohen S., et al. (2016). Directed elimination of senescent cells by inhibition of BCL-W and BCL-XL. Nat. Commun. 7, 11190. 10.1038/ncomms11190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Xie Y., Chen H., Lv L., Yao J., Zhang M., et al. (2020). Foxo4-dri alleviates age-related testosterone secretion insufficiency by targeting senescent leydig cells in aged mice. Aging 12, 1272–1284. 10.18632/aging.102682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Yu L. (2021). Sirtuin 1 activated by SRT1460 protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 78 (3), 271–281. 10.3233/CH-201061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Li Y., Zhou D., Tan R. J., Liu Y. (2013). Loss of klotho contributes to kidney injury by derepression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24, 771–785. 10.1681/ASN.2012080865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Doornebal E. J., Pirtskhalava T., Giorgadze N., Wentworth M., Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H., et al. (2017). New agents that target senescent cells the flavone, fisetin, and the BCL-X-L inhibitors, A1331852 and A1155463. Aging 9, 955–963. 10.18632/aging.101202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang K., Jiang X. Y., Liu R. B., Ye C., Wang Y., Wang Y., et al. (2021). Formononetin activates the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway via Sirt1 to improve diabetic renal fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 616378. 10.3389/fphar.2020.616378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou D., Wu W., He Y., Ma S., Gao J. (2018). The role of klotho in chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 19, 285. 10.1186/s12882-018-1094-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]