Abstract

Empathy—understanding and sharing the feelings and experiences of others—is one of our most important social capacities. Music is a social stimulus in that it involves communication of mental states, imitation of behavior, and synchronization of movements. As empathy and music are so closely linked, we investigated whether higher empathy is associated with stronger social bonding in interpersonal interactions that feature music. In two studies, participants watched videos in which we manipulated interpersonal synchrony between the movements of a virtual self and a virtual other person during walking with instrumental music or a metronome. In both studies, temporally aligned movements increased social bonding with the virtual other and higher empathy was associated with increased social bonding in movement interactions that featured music. Additionally, in Study 1, participants with lower empathy felt more connected when interacting with a metronome compared to music. In Study 2, higher trait empathy was associated with strong increases of social bonding when interacting with a temporally aligned virtual other, but only weak increases of social bonding with a temporally misaligned virtual other. These findings suggest that empathy plays a multifaceted role in how we enjoy, interpret, and use music in social situations.

Keywords: empathy, social bonding, music, synchronization, entrainment, joint action, affiliation

Empathy is a multidimensional concept that describes the understanding and sharing of viewpoints and emotions of others. Representing some of the most central aspects of social functioning, empathy results from the interplay between trait capacities and state influences (Cuff et al., 2016) comprising an individual’s cognitive, perspective-taking capabilities, and emotional reactivity (Davis, 1980). High empathy is positively associated with prosocial behavior (Eisenberg & Miller, 1987; Paciello et al., 2013) and negatively associated with social prejudice (Batson et al., 1997; Miklikowska, 2018).

Music is a social phenomenon in that we make, listen to, and dance to music together. In musical activities, we express attitudes, elicit emotions, imitate behavior, and synchronize movements, creating a feeling of togetherness (Cross et al., 2012). The social nature of musical stimuli explains why empathy is important for understanding emotions in music (Eerola et al., 2016; Egermann & McAdams, 2013; Wöllner, 2012) and why moving synchronously with music can increase prosocial behavior, interpersonal closeness, and cooperation (Cirelli et al., 2014; Kirschner & Tomasello, 2010; Stupacher, Maes, et al., 2017; Stupacher, Wood, & Witte, 2017; Wiltermuth & Heath, 2009).

Previous research suggests that music listening and musical interactions can promote empathy (Clarke et al., 2015; Greenberg et al., 2015; Rabinowitch et al., 2013). Vice versa, more empathic individuals may be more sensitive to social information in musical contexts (Keller et al., 2014). Participant pairs with higher empathic perspective-taking scores were more synchronized in a joint music-making task than participant pairs with low empathic perspective-taking scores, suggesting that sensorimotor mechanisms are crucial for simulating and anticipating the actions of another person in social interactions that feature music (Novembre et al., 2019). However, findings of Carlson and colleagues (2019) suggest that the relationship between empathy and interpersonal movement synchronization in musical contexts might be less stable than one would assume. In contrast to Novembre and colleagues’ (2019) findings and against Carlson and colleagues’ hypotheses, dancing pairs in which both partners had high trait empathy were perceived as moving less similar and less interactive than dancing pairs in which one partner had high and the other low trait empathy. These divergent findings reveal that it remains a debated question how empathy affects social bonding and well-being when moving to music in pairs or groups.

We investigated whether individuals with high empathy experience stronger interpersonal closeness in movement interactions that feature music compared to individuals with low empathy. We tested this hypothesis in two studies that used a social entrainment video paradigm (Stupacher et al., 2020; Stupacher, Maes, et al., 2017) in which participants with individual differences in empathic responsiveness rated the interpersonal closeness toward a virtual partner moving temporally aligned or misaligned with the beat of music or a metronome. In Study 1 (N = 146), the musical stimulus consisted of one excerpt from a jazz trio piece (“Elevation of Love” by Esbjörn Svensson Trio). Study 2 (N = 162) included three musical excerpts from the genres pop, funk, and jazz to test the generalizability of the results.

Study 1

Method

Participants

We analyzed data of 146 participants (mean age = 27.8 years, SD = 8.6; 88 female, 57 male, 1 other) based on sample sizes of previous experiments using similar paradigms (Stupacher et al., 2020; Stupacher, Maes, et al., 2017). Eighty-eight participants were Danish; the other 58 participants had 30 different nationalities. One additional participant was excluded because they gave the lowest rating on every item of the empathy questionnaire. Informed consent was provided and the study was approved by the IRB at the Danish Neuroscience Centre.

Stimuli and design

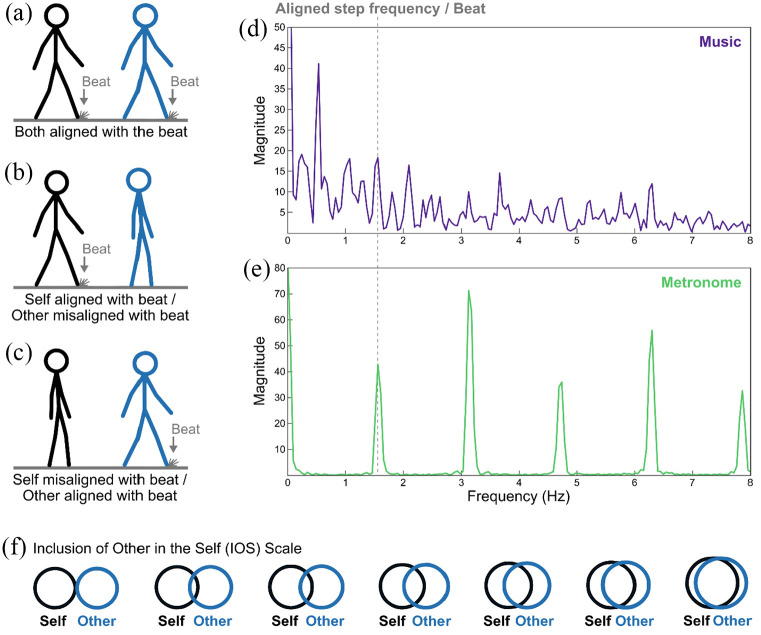

Participants rated six videos with a length of 17 s each (see Supplemental material online). These videos showed the following two walking stick figures: a black one and a blue one. The black figure represented the participants—hereafter, referred to as virtual self—and the blue figure represented another person—hereafter, referred to as virtual other. The manipulated independent variables were movement and music. The variable movement had the following three levels: (1) both figures aligned with the beat, (2) self aligned with the beat and other misaligned, and (3) self misaligned with the beat and other aligned (Figure 1(a) to (c)). The variable music had the following two levels: (1) music and (2) metronome (Figure 1(d) and (e); Supplemental material online). The musical piece was an excerpt of “Elevation of Love” by Esbjörn Svensson Trio in 6/8 m with a tempo of 94 beats per minute (bpm)/638 ms when counting binary subdivisions with subdivisions at 188 bpm (Figure 1(d)). The metronome consisted of a snare drum with an inter onset interval of 94 bpm and a hi-hat with a tempo of 188 bpm (Figure 1(e)). Temporally aligned figures had a step frequency of 94 bpm and the foot hit the ground on the beat of the music or the metronome. The moment of the foot hitting the ground was additionally marked by a “dust cloud” on the ground (see Figure 1). Temporally misaligned figures had a step frequency of 80 bpm/750 ms with a 125 ms delayed first step. This manipulation of frequency and phase ensured that the misaligned movement combinations resulted in constantly changing phase relationships between the steps of the two figures.

Figure 1.

(a to c) The Three Different Movement Alignment Levels of the Social Entrainment Video Paradigm in Study 1. Participants Imagined That They Are the Black Figure and That the Blue Figure Represents an Unknown Other Person. (d and e) Frequency Spectra of the Note-Onset Interval Series of the Music and Metronome Stimuli Detected by mironsets in the MIR Toolbox (Lartillot & Toiviainen, 2007) for MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). The Dashed Gray Line Represents the Beat of the Audio Stimuli and the Temporally Aligned Step Frequency of the Visual Stimuli, Which Was 94 bpm/638 ms. The Temporally Misaligned Step Frequency Was 80 bpm/750 ms. (f) Adapted Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale (Aron et al., 1992).

Procedure and ratings

Participants watched each of the six videos in randomized orders and imagined that the black figure represented themselves and that the blue figure represented an unknown person (Stupacher et al., 2020; Stupacher, Maes, et al., 2017). After each video, they rated social bonding with the virtual other and their well-being as the virtual self.

Social bonding was operationalized as the dependent variable Inclusion of Other in the Self (IOS; Aron et al., 1992; Figure 1(f)). Participants chose a position on a 100-point visual analogue scale that best described the relationship between their virtual self and the virtual other person.

Well-being was measured by the question “How did you feel in this situation as the black figure?” that participants answered on a 100-point visual analogue scale. We included this dependent variable because Stupacher, Maes, and colleagues (2017) found an effect of movement synchrony and music on well-being in a similar paradigm. How well-being is affected by trait empathy in these types of virtual social interactions remains an open question. Additionally, well-being addresses a more introversive aspect of social interactions than the IOS.

After rating all six videos, participants rated the familiarity with the music, the enjoyment of the music, and the perceived beat clarity of the music. At the end of the survey, participants filled out the Brief Form of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (B-IRI; Ingoglia et al., 2016). Empathy was operationalized as the overall score of the B-IRI including the subscales fantasy, perspective taking, empathic concern, and personal distress. Data were collected online on soscisurvey.de (SoSci Survey GmbH, Munich, Germany).

Data analysis

Using the lmer function from R’s (R Core Team, 2018) lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015), we modeled the dependent variables IOS and well-being in linear mixed effects models (Table 1). All models allowed for a random intercept per participant to control for participant level variability of IOS and well-being ratings. The full models included the following fixed effects: Movement (both aligned with the beat vs. self aligned/other misaligned vs. self misaligned/other aligned), music (music vs. metronome), and empathy.

Table 1.

Mixed Effects Models for the Dependent Variables Inclusion of Other in the Self (IOS) and Well-Being Investigating the Effects of the Independent Variables Movement, Music, and Empathy in Study 1.

| Model | AIC | BIC | Marg. R2 | Cond. R2 | Model fit improvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2(df) | p | |||||

| Dependent variable: IOS | ||||||

| M0: IOS null model | 8,345 | 8,359 | .234 | |||

| M1: IOS ~ movement (vs. M0) | 7,845 | 7,869 | .318 | .615 | 503.52 (2) | <.001 |

| M2: IOS ~ movement + music (vs. M1) | 7,843 | 7,872 | .320 | .617 | 4.27 (1) | .039 |

| M3: IOS ~ movement × music (vs. M2) | 7,846 | 7,884 | .320 | .617 | 0.90 (2) | .637 |

| M4: IOS ~ movement + music + empathy (vs. M2) | 7,845 | 7,878 | .319 | .618 | 0.02 (1) | .881 |

| M5: IOS ~ movement + music × empathy (vs. M2) | 7,837 | 7,875 | .323 | .623 | 10.33 (2) | .006 |

| M6: IOS ~ movement × music × empathy (vs. M5) | 7,847 | 7,914 | .323 | .622 | 1.25 (6) | .974 |

| Dependent variable: Well-being | ||||||

| M0: Well-being null model | 8,175 | 8,189 | .205 | |||

| M1: Well-being ~ movement (vs. M0) | 8,001 | 8,025 | .143 | .376 | 177.40 (2) | <.001 |

| M2: Well-being ~ movement + music (vs. M1) | 7,967 | 7,996 | .168 | .405 | 35.97 (1) | <.001 |

| M3: Well-being ~ movement × music (vs. M2) | 7,968 | 8,007 | .170 | .407 | 3.05 (2) | .217 |

| M4: Well-being ~ movement + music + empathy (vs. M2) | 7,969 | 8,003 | .167 | .407 | 0.03 (1) | .863 |

| M5: Well-being ~ movement + music × empathy (vs. M2) | 7,957 | 7,996 | .177 | .417 | 14.02 (2) | <.001 |

| M6: Well-being ~ movement × music × empathy (vs. M5) | 7,966 | 8,033 | .178 | .418 | 3.70 (6) | .718 |

AIC: Akaike information criterion; BIC: Bayesian information criterion; IOS: inclusion of other in the self.

All models included a random effect for participants. The Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), variance explained by fixed effects (marginal R2), and variance explained by fixed and random effects (conditional R2) are provided. χ2 and p values refer to model comparisons against models indicated in parentheses using likelihood ratio tests. For both dependent variables, model M5 describes the data best (marked in bold).

Results

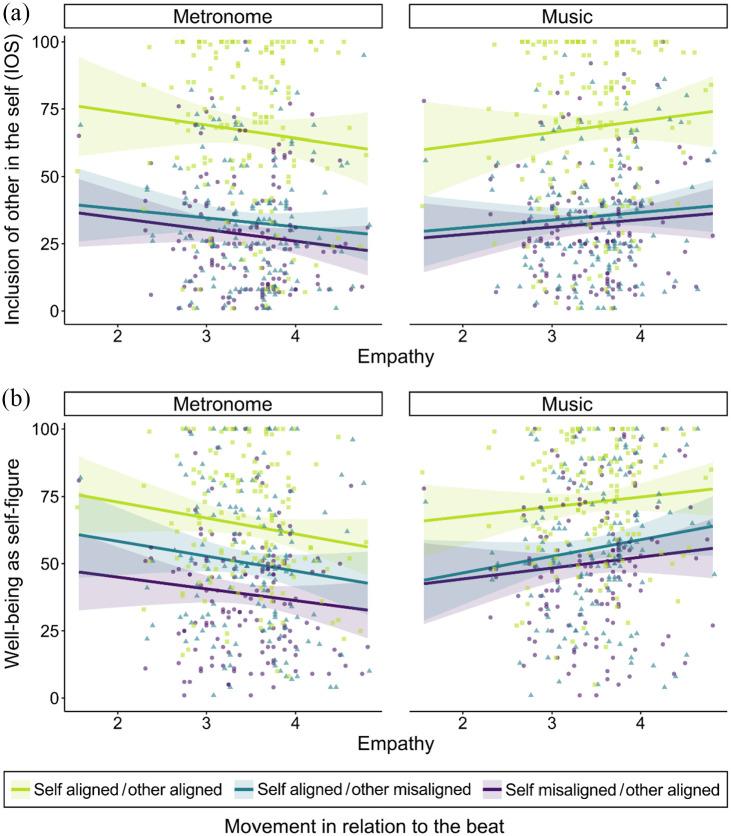

Participants with higher empathy experienced higher interpersonal closeness in virtual movement interactions that featured music, whereas participants with lower empathy experienced higher interpersonal closeness in virtual movement interactions that featured a metronome, t(726) = 3.21, p = .006 (Table 2). Additionally, interpersonal closeness to the virtual other was higher for temporally aligned movements compared to misaligned movements (pairwise comparisons in Table 2). These results are reflected in the comparisons of linear mixed effects models for the dependent variable IOS: The best fitting model indicated an interaction between music and empathy and a main effect of movement (Figure 2(a), Table 1).

Table 2.

Pairwise Comparisons of Individual Factor Levels in the Best Fitting Linear Mixed Effects Models in Study 1.

| Model | Pairwise comparison | Estimate | SE | df | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOS ~ movement + music × empathy | Self misaligned/other aligned—self aligned/other misaligned | −3.74 | 1.15 | 726 | −2.48 | .053 | [−7.5, 0.03] |

| Self misaligned/other aligned—self aligned/other aligned | −37.13 | 1.15 | 726 | −24.63 | <.001 | [−40.9, −33.4] | |

| Self aligned/other misaligned—self aligned/other aligned | −33.39 | 1.15 | 726 | −22.15 | <.001 | [−37.2, −29.6] | |

| Empathy|metronome—empathy|music (slope) | −7.47 | 2.33 | 726 | −3.21 | .006 | [−13.3, −1.6] | |

| Well-being ~ movement + music × empathy | Self misaligned/other aligned—self aligned/other misaligned | −8.67 | 1.68 | 726 | −5.15 | <.001 | [−12.9, −4.5] |

| Self misaligned/other aligned—self aligned/other aligned | −24.30 | 1.68 | 726 | −14.43 | <.001 | [−28.5, −20.1] | |

| Self aligned/other misaligned—self aligned/other aligned | −15.64 | 1.68 | 726 | −9.28 | <.001 | [−19.9, −11.4] | |

| Empathy|metronome—empathy|music (slope) | −9.74 | 2.60 | 726 | −3.75 | <.001 | [−16.2, −3.2] |

CI: confidence interval; IOS: inclusion of other in the self; SE: standard error.

Comparisons were computed using the emmeans package in R (Lenth et al., 2020). p-values and confidence intervals are Bonferroni-corrected for four comparisons.

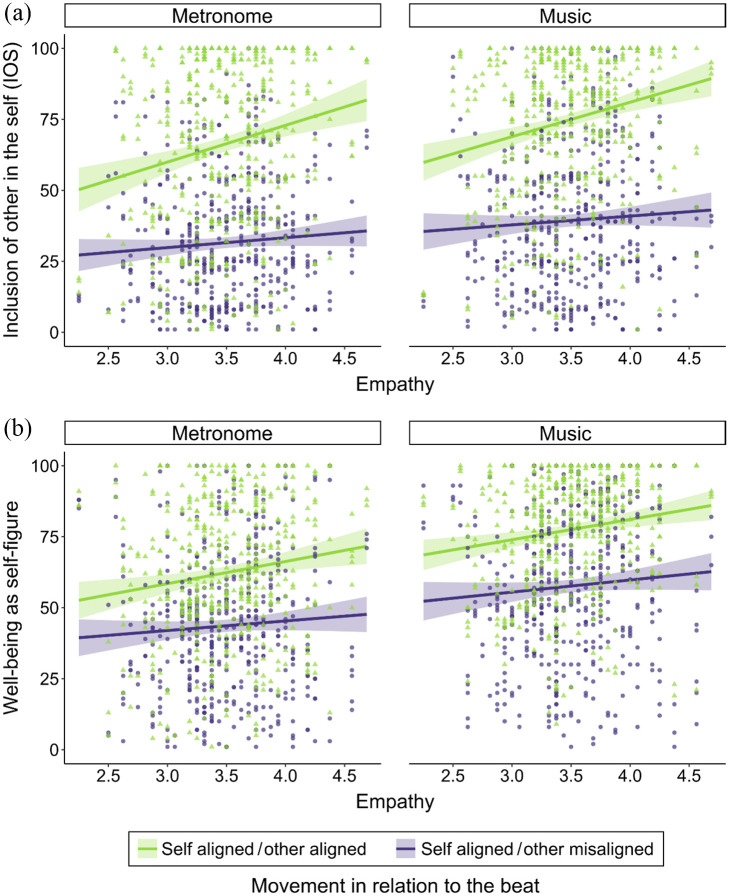

Figure 2.

Individual Data Points and Linear Predictions of Interpersonal Closeness as Measured by IOS (Aron et al., 1992) and Well-Being in Relation to Participants’ Trait Empathy in Study 1. Shaded Areas Represent 95% Confidence Intervals. (a) IOS for All Three Movement Conditions in Interactions With Metronome and Music. (b) Well-Being for All Three Movement Conditions in Interactions With Metronome and Music.

Similarly, for the dependent variable well-being, the best fitting model indicated a main effect of movement and an interaction between music and empathy (Figure 2(b), Table 1). The significant interaction suggests that participants with higher empathy felt better when moving together with music, whereas participants with lower empathy felt better when moving together with a metronome, t(726) = 3.75, p < .001 (Table 2). The significant main effect of movement indicates that well-being was higher for temporally aligned movements compared to both misaligned movement conditions and higher for self aligned/other misaligned compared to self misaligned/other aligned (pairwise comparisons in Table 2).

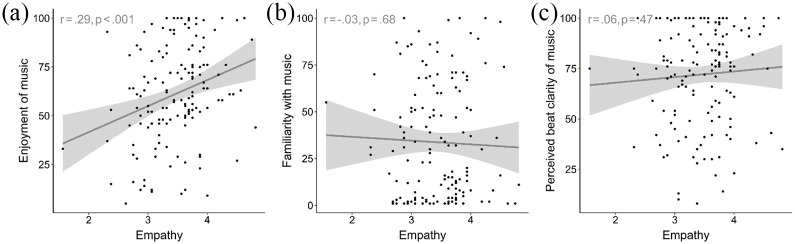

Empathy was positively correlated with overall enjoyment of the music, r(144) = .29, p < .001 (Figure 3(a)). Correlations between empathy and familiarity with the music and between empathy and perceived beat clarity of the music were nonsignificant (Figure 3(b) and (c)).

Figure 3.

Individual Data Points and Linear Predictions of (a) Enjoyment of the Musical Stimulus, (b) Familiarity With the Musical Stimulus, and (c) Perceived Beat Clarity in Relation to Participants’ Trait Empathy in Study 1. Shaded Areas Represent 95% Confidence Intervals. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients (df = 144) Are Provided in the Top Left Corners.

Study 2

To increase the generalizability of the video paradigm, we extended the acoustic stimuli from one instrumental music clip and one metronome in Study 1 to three instrumental music clips and three metronomes in Study 2.

Method

Participants

We analyzed data of 162 participants (mean age = 30.4 years, SD = 9.7; 114 female, 48 male). Fifty-eight participants were Danish; the other 104 participants had 41 different nationalities with the largest sub-samples being from Great Britain (n = 19), the United States (n = 8), and Germany (n = 6). Ten additional participants were excluded because they reported that they participated in a similar experiment before. Informed consent was provided and the study was approved by the IRB at the Danish Neuroscience Centre.

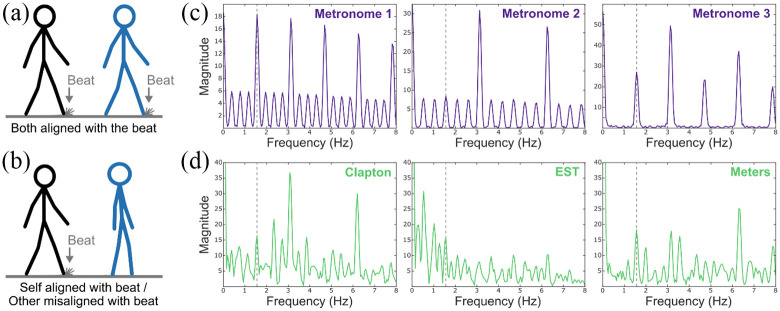

Stimuli and design

Participants rated 12 videos with a length of 11 s each (see Supplemental material online). Similar to Study 1, these videos showed the following two walking stick figures: a black one representing the virtual self and a blue one representing the virtual other. The manipulated independent variables were movement and music. In contrast to Study 1, the variable movement had only the following two levels: (1) both figures aligned with the beat and (2) self aligned with the beat and other misaligned. The variable music had the following two levels: (1) music and (2) metronome (Figure 4; Supplemental material online). The musical pieces were instrumental excerpts of “My Father’s Eyes” by Eric Clapton (4/4 meter), “Elevation of Love” by Esbjörn Svensson Trio (6/8 meter; see Study 1), and “Thinking” by the Meters (4/4 meter). All musical pieces had a tempo of 94 bpm/638 ms (Figure 4(d)). The three metronomes consisted of 4/4, 6/8, and 2/4 meter at 94 bpm (Figure 4(c)). Identical to Study 1, temporally aligned figures had a step frequency of 94 bpm and the foot hit the ground on the beat of the music or the metronome. The moment of the foot hitting the ground was additionally marked by a “dust cloud” on the ground (see Figure 4). In contrast to Study 1, temporally misaligned figures started to walk with a step frequency of 78 bpm/769 ms with a 233 ms delayed first step, sped up to 86 bpm/698 ms, and slowed down to the start step frequency again.

Figure 4.

(a and b) The Two Different Movement Alignment Levels of the Social Entrainment Video Paradigm in Study 2. (c and d) Frequency Spectra of the Note-Onset Interval Series of the Three Metronome Stimuli (c) and the Three Music Stimuli (d) Detected by mironsets in the MIR Toolbox (Lartillot & Toiviainen, 2007) for MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). The Dashed Gray Line Represents the Beat of the Audio Stimuli and the Temporally Aligned Step Frequency of the Visual Stimuli, Which Was 94 bpm/638 ms.

Procedure and ratings

Similar to Study 1, participants watched each of the 12 videos in randomized orders and imagined that the black figure represented themselves and that the blue figure represented an unknown person (Stupacher et al., 2020; Stupacher, Maes, et al., 2017). They rated IOS and well-being in each video on a 100-point visual analogue scale. After the video rating, participants rated how much they enjoyed the music. At the end of the survey, participants filled out the Brief Form of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (B–IRI; Ingoglia et al., 2016). As in Study 1, the mean of the B–IRI items was used as empathy value. Data were collected online on soscisurvey.de (SoSci Survey GmbH, Munich, Germany).

Data analysis

We modeled the dependent variables IOS and well-being in linear mixed effects models using the lmer function from R’s (R Core Team, 2018) lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). All models allowed for a random intercept per participant to control for participant level variability of IOS and well-being ratings and for random intercepts for the six stimuli (three metronomes and three music excerpts). The full models included the following fixed effects: Movement (both aligned with the beat vs. self aligned/other misaligned), music (music vs. metronome), and empathy.

Results

For both dependent variables, IOS and well-being, ratings were higher when moving with a temporally aligned virtual other compared to a misaligned virtual other and higher for virtual movement interactions that featured music compared to metronomes. Participants with higher empathy rated IOS and well-being higher compared to participants with lower empathy. For IOS ratings, the best fitting model additionally indicated an interaction between movement and empathy (Figure 5(a) and Table 3). For well-being ratings, the best fitting model only included main effects of movement, music, and empathy; the interaction between movement and empathy tended to improve the fit of the model but was not significant, p = .063; Figure 5(b) and Table 3.

Figure 5.

Individual Data Points and Linear Predictions of Interpersonal Closeness as Measured by IOS (Aron et al., 1992) and Well-Being in Relation to Participants’ Trait Empathy in Study 2. Shaded Areas Represent 95% Confidence Intervals. (a) IOS for the Two Movement Levels With Metronome and Music. (b) Well-Being for the Two Movement Levels With Metronome and Music.

Table 3.

Mixed Effects Models for the Dependent Variables Inclusion of Other in the Self (IOS) and Well-Being Investigating the Effects of the Independent Variables Movement, Music, and Empathy in Study 2.

| Model | AIC | BIC | Marg. R2 | Cond. R2 | Model fit improvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2(df) | p | |||||

| Dependent variable: IOS | ||||||

| M0: IOS null model | 18,574 | 18,596 | .248 | |||

| M1: IOS ~ movement (vs. M0) | 17,449 | 17,477 | .323 | .601 | 1127(1) | <.001 |

| M2: IOS ~ movement + music (vs. M1) | 17,441 | 17,474 | .341 | .600 | 10.21(1) | .001 |

| M3: IOS ~ movement × music (vs. M2) | 17,443 | 17,482 | .341 | .600 | 0.17(1) | .681 |

| M4: IOS ~ movement + music + empathy (vs. M2) | 17,435 | 17,474 | .354 | .601 | 7.41(1) | .006 |

| M5: IOS ~ movement + music × empathy (vs. M4) | 17,437 | 17,482 | .354 | .601 | 0.09(1) | .762 |

| M6: IOS ~ movement × music + empathy (vs. M4) | 17,437 | 17,482 | .354 | .601 | 0.17(1) | .681 |

| M7: IOS ~ movement × empathy + music (vs. M4) | 17,416 | 17,461 | .358 | .605 | 21.45(1) | <.001 |

| M8: IOS ~ movement × empathy × music (vs. M7) | 17,422 | 17,483 | .358 | .605 | 0.28(3) | .965 |

| Dependent variable: well-being | ||||||

| M0: Well-being null model | 17,789 | 17,811 | .352 | |||

| M1: Well-being ~ movement (vs. M0) | 17,358 | 17,386 | .128 | .492 | 432(1) | <.001 |

| M2: Well-being ~ movement + music (vs. M1) | 17,350 | 17,383 | .203 | .486 | 10.54(1) | .001 |

| M3: Well-being ~ movement × music (vs. M2) | 17,351 | 17,390 | .203 | .486 | 0.45(1) | .502 |

| M4: Well-being ~ movement + music + empathy (vs. M2) | 17,347 | 17,386 | .212 | .487 | 4.69(1) | .030 |

| M5: Well-being ~ movement + music × empathy (vs. M4) | 17,349 | 17,394 | .212 | .487 | 0.01(1) | .954 |

| M6: Well-being ~ movement × music + empathy (vs. M4) | 17,349 | 17,393 | .212 | .487 | 0.45(1) | .502 |

| M7: Well-being ~ movement × empathy + music (vs. M4) | 17,346 | 17390 | .212 | .488 | 3.45(1) | .063 |

| M8: Well-being ~ movement × empathy × music (vs. M4) | 17,351 | 17,412 | .212 | .488 | 4.06(4) | .398 |

AIC: Akaike information criterion; BIC: Bayesian information criterion; IOS: inclusion of other in the self.

All models included random effects for participants and stimuli. The Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), variance explained by fixed effects (marginal R2), and variance explained by fixed and random effects (conditional R2) are provided. χ2 and p values refer to model comparisons against models indicated in parentheses using likelihood ratio tests. The models that describe the data best are marked in bold.

The best fitting IOS model (IOS ~ movement × empathy + music) resulted in significant pairwise comparisons of movement (Misaligned—Aligned contrast estimate −35.2, SE = 0.88, p < .001, CI [−36.9, −33.4]), music (Metronome—Music contrast estimate −8.18, SE = 1.75, p = .010, CI [−13.1, −3.3]), and empathy (slope estimate 7.91, SE = 2.89, p = .007, CI [2.2, 13.6]). The interaction between empathy and movement was significant (Empathy|Misaligned—Empathy|Aligned estimate −9.24, SE = 1.99, p < .001, CI [−13.1, −5.3]).

The best fitting well-being model (Well-being ~ movement + empathy + music) resulted in significant pairwise comparisons of movement (Misaligned—Aligned contrast estimate −19.3, SE = 0.87, p < .001, CI [−21.0, −17.6]), music (Metronome—Music contrast estimate −14.60, SE = 3.19, p = .010, CI [−23.4, −5.7]), and empathy (slope estimate 5.65, SE = 2.60, p = .031, CI [0.5, 10.8]).

Similar to Study 1, empathy was positively correlated with the mean of the enjoyment of music, r(160) = .16, p = .049, indicating that higher empathy was associated with more enjoyment of the music.

General discussion

Music is about humans interacting with each other; it is about communicating and understanding each other’s mental states and about coordinating and synchronizing each other’s movements and behaviors. These social interactions are key aspects of how music becomes meaningful. Our findings suggest that individual traits, such as empathy, can affect how we bond with others and how we feel in social interactions that feature music.

Overall, our results demonstrate that temporally aligned movements between virtual self and other increase social bonding and well-being. This positive effect of synchronized movement was found when virtual self and other were interacting with music or a metronome, supporting previous studies that showed a prosocial effect of interpersonal movement synchronization (Demos et al., 2012; Hove & Risen, 2009; Kokal et al., 2011; Stupacher et al., 2020; Stupacher, Maes, et al., 2017; Valdesolo & DeSteno, 2011; Wiltermuth & Heath, 2009). The consensus between these studies underlines the notion that prosocial consequences and positive emotional effects of moving to music in social settings are cultural universals and might be evolutionary adaptations (Savage et al., 2021; Trainor, 2015).

Our findings suggest that music plays a special role when moving in social settings. In both studies, videos in which virtual self and other were moving with music received higher ratings of social closeness compared to videos with metronomes. Additionally, both studies showed that when interacting with music, higher trait empathy was associated with stronger social bonding between virtual self and virtual other. However, two different interactions of social closeness ratings—an empathy × music interaction in Study 1 and an empathy × movement interaction in Study 2—revealed that the role of empathy in social interactions with music is multifaceted and may be influenced by subtle changes in the musical and social environment.

The empathy × music interaction of social closeness and well-being ratings in Study 1 suggests that individuals with high trait empathy may feel better and bond more with others when interacting with music compared to a simple timekeeper, such as a metronome. In contrast, individuals with lower trait empathy may feel better and bond more with others when interacting with a simple nonmusical timekeeper, which is connected to less social expectations and norms.

The empathy × movement interaction of social closeness ratings in Study 2 suggests that higher trait empathy may be associated with strong increases of social bonding when interacting with a temporally aligned other person, but only weak increases of social bonding with a temporally misaligned other person. In other words, when it comes to social bonding, individuals with less empathy may differentiate less between temporally aligned and misaligned others in interpersonal movement interactions compared to individuals with high empathy. A similar tendency can be seen in the ratings of well-being.

An explanation for why the empathy × music interaction of social closeness and well-being ratings was significant in Study 1 but not significant in Study 2 could be the selection of musical excerpts. Study 1 only featured an excerpt of the title “Elevation of Love” by Esbjörn Svensson Trio, which can be described as rhythmically driving but melancholic. Study 2, however, included a broader range of instrumental musical excerpts that, besides “Elevation of Love,” featured “Thinking” a groovy piece by The Meters, and “My Father’s Eyes,” a standard pop/rock piece by Eric Clapton. The empathy × music interaction in Study 1 might therefore represent the influence of empathy on social bonding with melancholic music. For music in general and for more uplifting music, this influence might be attenuated or even disappear. Huron and Vuoskoski (2020) argue that individuals who enjoy sad music more than others might have a specific pattern of trait empathy, which makes them experience pleasure through compassion and empathetic engagement. The results of Study 1 show that higher trait empathy was associated with more enjoyment of the excerpt from “Elevation of Love.” It is therefore possible that participants on the upper end of the trait empathy scale experienced more compassion with the music compared to the metronome, which could be reflected in stronger feelings of social closeness.

A potential reason for why we only found an interaction of social closeness ratings between empathy and movement in Study 2 is that Study 1 included three movement alignment levels, whereas Study 2 only included two movement alignment levels, which could have made it easier for participants to differentiate between temporally aligned and temporally misaligned movements. Additionally, the misaligned virtual other in Study 2 was not just moving at a different frequency and delayed, but was also speeding up and slowing down, which made the timing of the movements even less predictable and the misalignment even more obvious.

Future studies could directly manipulate the emotional responses that the music evokes to investigate the influence of specific patterns of trait empathy, such as compassion in individuals who particularly enjoy sad music, on social bonding in movement interactions. To better understand the influence of the clarity of movement alignment or misalignment, a finer manipulation of phase and frequency differences between self and other is needed; for example, aligned versus almost aligned versus slightly misaligned versus misaligned movements. Another open question is whether phase misalignment, frequency misalignment, or a combination of both most strongly affects ratings of social closeness.

Empathy does not only influence how we interpret social interactions with music, but joint musical activities can also promote empathy (Clarke et al., 2015; Greenberg et al., 2015), especially in individuals with empathy deficits (Behrends et al., 2012). Following the empathy × music interaction in Study 1, it may be beneficial to use isochronous or very simple rhythms in movement- and music-supported educational and clinical approaches to increase empathy. This conclusion is speculative, however, and not directly supported by Study 2, in which we did not find an interaction between empathy and music. The discrepancy between the two studies could mean that different types of music have different effects on social bonding in individuals with high or low empathy. Individuals with empathy deficits might therefore benefit most from selecting their own preferred music when joining group interactions that feature musical rhythm (Rabinowitch, 2015).

Empathy deficits are characteristic in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In a study with a beat-based communication task, cognitive empathy toward a synchronous compared to asynchronous partner increased in neurotypical participants but not in participants with ASD (Koehne et al., 2016). The empathy × movement interaction in Study 2 is comparable to Koehne and colleagues’ findings; Participants with low empathy rated the social closeness toward temporally aligned and misaligned virtual others quite similar, whereas participants with high empathy rated social closeness toward the temporally aligned virtual other substantially higher than the misaligned virtual other.

A future opportunity is to explore physiological and psychological benefits of social musical activities involving synchronized movements for individuals with low trait empathy. Given the many facets of empathy and the complexity of social interactions with music, the collection of more empirical evidence is crucial. Accumulated insights gained from empirical studies, such as the current ones, can be applied to educational programs and clinical interventions that use joint musical activities to strengthen empathy and social bonding.

In both studies, trait empathy was positively correlated with enjoyment of the musical pieces in the virtual social interactions. This finding is in line with recent studies suggesting that trait empathy is associated with activity in prefrontal and reward areas in the brain when listening to music (Wallmark et al., 2018) and with greater enjoyment of dancing (Bamford & Davidson, 2019). A future challenge is to disentangle the close relationships between enjoyment of music and dancing, empathy, and social bonding, which could be achieved by choosing individual musical pieces for participants in joint musical activities and controlling for the enjoyment of these pieces. Importantly, our findings show that the perceived beat clarity of the used musical piece did not correlate with empathy, which makes it unlikely that differences in rhythm perception or beat induction influenced ratings of interpersonal closeness and well-being with music.

In sum, our findings provide insights into how our enjoyment, interpretation, and use of music in social situations may be related to our empathy traits. Both studies suggest that when moving together with music, higher empathy is associated with increased social bonding and well-being. Interactions of social closeness between empathy and the type of musical stimulus in Study 1 and movement alignment in Study 2 reveal that the interplay between these factors is not easily generalizable and may be influenced by small changes in the environment. We need to accumulate more evidence to fully understand how empathy influences the fascinating prosocial effects of moving together with music.

Footnotes

Author note: Jan Stupacher is now affiliated to Institute of Psychology, University of Graz, Graz, Austria.

Author contributions: J.S. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data curation, data analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. J.M. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, and data curation. P.V. contributed to conceptualization and writing—review and editing.

Data availability statement: The data and analysis scripts supporting the findings of these studies are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Center for Music in the Brain is funded by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF 117). Jan Stupacher is supported by an Erwin Schrödinger fellowship from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF J4288).

ORCID iD: Jan Stupacher  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2179-2508

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2179-2508

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Aron A., Aron E. N., Smollan D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. [Google Scholar]

- Bamford J. M. S., Davidson J. W. (2019). Trait empathy associated with agreeableness and rhythmic entrainment in a spontaneous movement to music task: Preliminary exploratory investigations. Musicae Scientiae, 23(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Batson C. D., Polycarpou M. P., Harmon-Jones E., Imhoff H. J., Mitchener E. C., Bednar L. L., Klein T. R., Highberger L. (1997). Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrends A., Müller S., Dziobek I. (2012). Moving in and out of synchrony: A concept for a new intervention fostering empathy through interactional movement and dance. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(2), 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E., Burger B., Toiviainen P. (2019). Empathy, entrainment, and perceived interaction in complex dyadic dance movement. Music Perception, 36(4), 390–405. [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli L. K., Wan S. J., Trainor L. J. (2014). Fourteen-month-old infants use interpersonal synchrony as a cue to direct helpfulness. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369, 20130400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke E., DeNora T., Vuoskoski J. (2015). Music, empathy and cultural understanding. Physics of Life Reviews, 15, 61–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross I., Laurence F., Rabinowitch T.-C. (2012). Empathy and creativity in group musical practices: Towards a concept of empathic creativity. In McPherson G. E., Welch G. F. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of music education (Vol. 2, pp. 336–353). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cuff B. M. P., Brown S. J., Taylor L., Howat D. J. (2016). Empathy: A review of the concept. Emotion Review, 8(2), 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Demos A. P., Chaffin R., Begosh K. T., Daniels J. R., Marsh K. L. (2012). Rocking to the beat: Effects of music and partner’s movements on spontaneous interpersonal coordination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(1), 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eerola T., Vuoskoski J. K., Kautiainen H. (2016). Being moved by unfamiliar sad music is associated with high empathy. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egermann H., McAdams S. (2013). Empathy and emotional contagion as a link between recognized and felt emotions in music listening. Music Perception, 31(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N., Miller P. A. (1987). The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1), 91–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D. M., Rentfrow P. J., Baron-Cohen S. (2015). Can music increase empathy? Interpreting musical experience through the Empathizing–Systemizing (E-S) theory: Implications for autism. Empirical Musicology Review, 10(1–2), 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hove M. J., Risen J. L. (2009). It’s all in the timing: Interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Social Cognition, 27(6), 949–960. [Google Scholar]

- Huron D., Vuoskoski J. K. (2020). On the enjoyment of sad music: Pleasurable compassion theory and the role of trait empathy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoglia S., Lo Coco A., Albiero P. (2016). Development of a brief form of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (B–IRI). Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(5), 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P. E., Novembre G., Hove M. J. (2014). Rhythm in joint action: Psychological and neurophysiological mechanisms for real-time interpersonal coordination. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369, 20130394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner S., Tomasello M. (2010). Joint music making promotes prosocial behavior in 4-year-old children. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(5), 354–364. [Google Scholar]

- Koehne S., Hatri A., Cacioppo J. T., Dziobek I. (2016). Perceived interpersonal synchrony increases empathy: Insights from autism spectrum disorder. Cognition, 146, 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokal I., Engel A., Kirschner S., Keysers C. (2011). Synchronized drumming enhances activity in the caudate and facilitates prosocial commitment—If the rhythm comes easily. PLOS ONE, 6(11), Article e27272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot O., Toiviainen P. (2007, September 10–15). A Matlab toolbox for musical feature extraction from audio [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Digital Audio Effects, Bordeaux, France. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R., Singmann H., Love J., Buerkner P., Herve M. (2020). Package “emmeans” (1.4.5). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

- Miklikowska M. (2018). Empathy trumps prejudice: The longitudinal relation between empathy and anti-immigrant attitudes in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 54(4), 703–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novembre G., Mitsopoulos Z., Keller P. E. (2019). Empathic perspective taking promotes interpersonal coordination through music. Scientific Reports, 9, 12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paciello M., Fida R., Cerniglia L., Tramontano C., Cole E. (2013). High cost helping scenario: The role of empathy, prosocial reasoning and moral disengagement on helping behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(1), 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitch T.-C. (2015). How, rather than what type of, music increases empathy. Empirical Musicology Review, 10(1–2), 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitch T.-C., Cross I., Burnard P. (2013). Long-term musical group interaction has a positive influence on empathy in children. Psychology of Music, 41(4), 484–498. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org

- Savage P. E., Loui P., Tarr B., Schachner A., Glowacki L., Mithen S., Fitch W. T. (2021). Music as a coevolved system for social bonding. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 44, E59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupacher J., Maes P.-J., Witte M., Wood G. (2017). Music strengthens prosocial effects of interpersonal synchronization—If you move in time with the beat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 72, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stupacher J., Witek M. A. G., Vuoskoski J. K., Vuust P. (2020). Cultural familiarity and individual musical taste differently affect social bonding when moving to music. Scientific Reports, 10, 10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupacher J., Wood G., Witte M. (2017). Synchrony and sympathy: Social entrainment with music compared to a metronome. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 27(3), 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- Trainor L. J. (2015). The origins of music in auditory scene analysis and the roles of evolution and culture in musical creation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370, 20140089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdesolo P., DeSteno D. (2011). Synchrony and the social tuning of compassion. Emotion, 11(2), 262–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallmark Z., Deblieck C., Iacoboni M. (2018). Neurophysiological effects of trait empathy in music listening. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, Article 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltermuth S. S., Heath C. (2009). Synchrony and cooperation. Psychological Science, 20(1), 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wöllner C. (2012). Is empathy related to the perception of emotional expression in music? A multimodal time-series analysis. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6(3), 214–223. [Google Scholar]